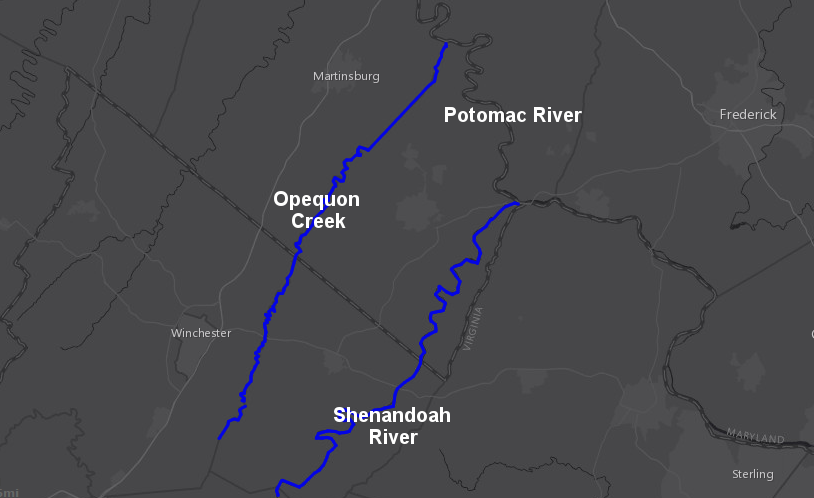

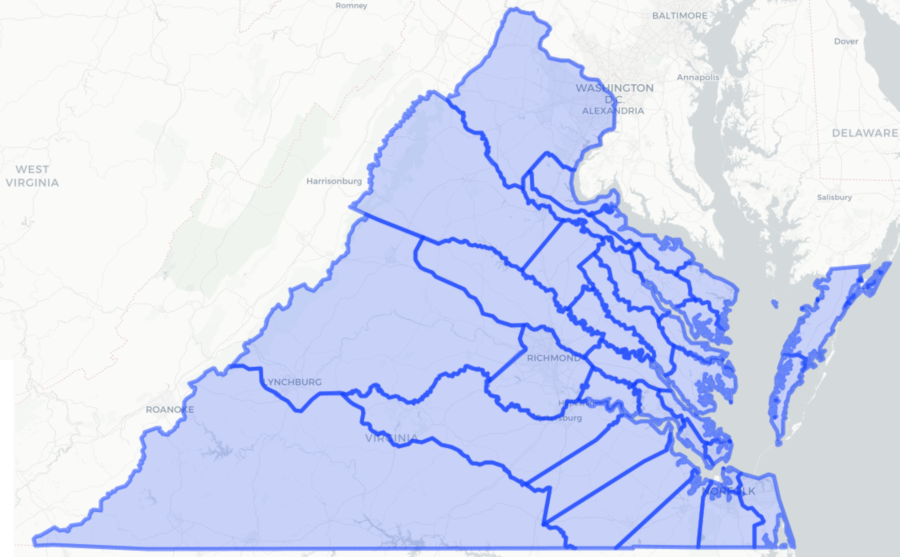

the 40,000 acres granted to the Van Meters were for lands west of the Shenandoah River, east of Opequon Creek, and south of the Potomac River

Source: ERSI, ArcGIS Online

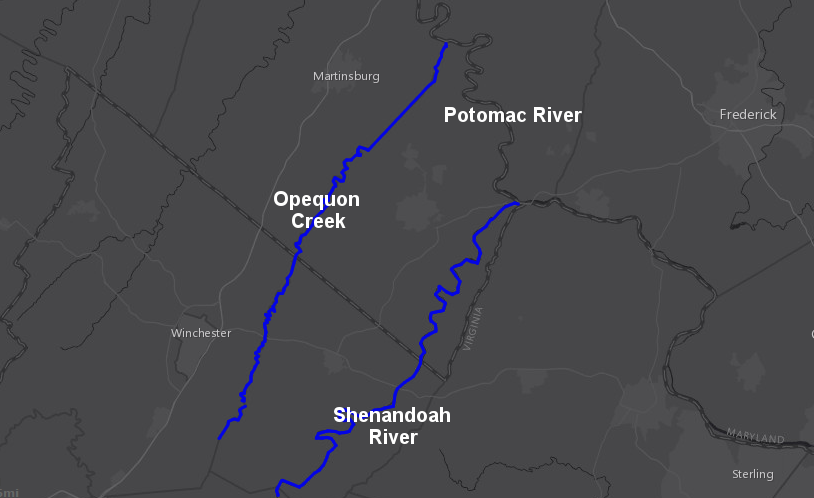

the 40,000 acres granted to the Van Meters were for lands west of the Shenandoah River, east of Opequon Creek, and south of the Potomac River

Source: ERSI, ArcGIS Online

After he became governor of Virginia in 1710, Alexander Spotswood became anxious to establish settlement west of the Blue Ridge of people who would be loyal to the colonial government at Williamsburg. His replacement, Governor Gooch, shared the same concern.

They feared the French would establish alliances with Native Americans who lived in the Ohio River watershed and block westward expansion of the English. They also viewed the gaps in the Blue Ridge as potential invasion routes of French soldiers working with raiders from the Shawnee, Delaware, or other Native American tribes.

In the 1730's, English settlement was just beginning to occupy the Piedmont west of the Fall Line. Governor Gooch was not willing to wait several decades for the natural population growth that would lead to English settlement in the valleys west of the mountains. He chose to recruit non-English immigrants, and targeted religious and economic refugees who had migrated from Germany, Scotland, and Ireland into Pennsylvania.

The governor and Council were also concerned in the 1730's about the colony's authority to issue grants for lands in the northern part of Virginia. Lord Fairfax had acquired full control of a grant that had originally been issued by Charles II in 1649. Based on the boundaries of the grant Fairfax's land agent, Robert Carter, was asserting exclusive right to sell lands west of the Blue Ridge in the lower (northern) part of the Shenandoah Valley. The Fairfax claim threatened the potential of the colonial government, based in Williamsburg, to give away land there in order to incentivize settlement.

Governor Gooch and the Council were in a hurry to sell lands west of the Blue Ridge before Lord Fairfax could gain control. If the officials in Williamsburg waited for officials in London to clarify land ownership, then the colonial government might lose the value of the treasury rights (10 shillings/100 acres) and annual quitrents (2 shillings/100 acres) on territory sold by Lord Fairfax.1

In addition, Lord Fairfax might sell large blocks of land to speculators and repeat the slow settlement pattern of the 1720's in the Piedmont, between the Fall Line and the Blue Ridge. Speculators, especially members of the gentry on the Council, acquired large grants and then held onto that land. Creating a plantation economy in the Piedmont based on slave-raised tobacco maximized the profits of the gentry - but delayed settlement by large numbers of white, Protestant, loyal-to-England settlers for a decade or more.

Both Lord Fairfax and Governor Gooch recognized that immigrants settling around Philadelphia could be attracted to Virginia's backcountry west of the Blue Ridge. In the Shenandoah Valley there was a risk of attack by French-supplied Native American raiders, but Virginia had two major incentives. Land could be sold at prices lower than Pennsylvania land, and officials in Williamsburg could offer clear title. In Pennsylvania, proprietary officials struggled to negotiate treaties with the Delaware, Susquehannocks, and other Native American groups before selling land that would accommodate westward expansion.

Settlers walking south from Pennsylvania in the 1730's had the option to stop and settle in Western Maryland. That involved a shorter walk from Philadelphia and required no crossing of the Potomac River. The Calverts were willing to give new backcountry settlers 100 acres and waive the requirement to pay quitrents for three years. However, title to Maryland's backcountry was unclear so long as the Calverts and Penns contested the location of the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary at the 40th degree of latitude.

On June 17, 1730, Governor Gooch and the Council issued "land orders" authorizing John and Isaac Van Meter to select 30,000 acres. The land orders allowed the brothers to survey parcels of land within a specified area, then bring those surveys back to the Secretary of the colony. The Secretary would then issue a deed ("patent") transferring title to the parcels.

The process for obtaining land via headrights and treasury rights required a county surveyor and county court to take specific actions before land was transferred into private ownership. In 1730, no county administered any lands west of the Blue Ridge.

The solution was to create a new county. That required lengthy negotiations with factions on Council and in House of Burgesses. In the meantime, to speed settlement and bypass the standard procedures for headrights and treasury rights, Governor Gooch and the Council issued land orders to grant large acreages to one or two individuals. Those individuals were authorized to select the parcels and arrange for surveys. Documents were filed with the Secretary of the colony, and patents were issued in Williamsburg rather than via a county court.

Between 1730-1732, the governor and Council issued nine large land orders for 385,000 acres west of the mountains. Orange County was created in 1734, four years after the first land order for 30,000 acres was issued to John and Isaac Van Meter.2

The Van Meter brothers had been born in New York, then moved to Pennsylvania. They took advantage of Governor Gooch's enthusiasm for settling the area west of the Blue Ridge as a buffer zone for protection against raids by Native Americans and the French moving down the Ohio River Valley. There were vast tracts of unsettled land east of the Blue Ridge and little demand for that land.

John Van Meter might have been exposed to the Virginia backcountry as early as 1725, while accompanying some Delaware raiders on an expedition against the Catawba in the Piedmont of North Carolina.3

In the 1730 land orders, John Van Meter was authorized to select an initial 10,000 acres between the North and South forks of the "Shenado" River, then 20,000 more acres west of the Shenandoah River, east of Opequon Creek, and south of the Potomac River:4

Isaac Van Meter was authorized to survey and patent an additional 10,000 acres. In total, the brothers received 40,000 acres from the colony as it raced to dispose of land before Lord Fairfax could establish his rights.

The basic formula for the colonial government's land orders was to authorize 1,000 acres of land for each family that the Van Meter brothers recruited and actually settled west of the Blue Ridge. After planting 20 families on the initial grant, John Van Meter would be entitled to 20,000 acres. Isaac Van Meter was required to settle 10 families to earn his extra 10,000 acres. John Van Meter managed his brother's grants, and Isaac did not come to Virginia.

The Van Meters considered purchasing the land from Lord Fairfax, and discussed the possibility with his land agent Robert "King" Carter. They also may have considered negotiating a deal with Native Americans who lived and hunted in the area, but they trusted only Israel Friend enough to sell him land at the mouth of Antietam Creek. Six chiefs, at least five of which were Conestoga, signed the Antietam deed in 1727.5

The Van Meter brothers finally calculated that they could acquire land from colonial officials in Williamsburg, with less cost and more options. Lord Fairfax's land agent, Robert Carter, objected to the Van Meter grants but Governor Gooch acted anyway.

The brothers were given great flexibility in choosing the best lands within a wide area. As described by one historian:6

Jost Hite (Joist Heydt) and Robert McKay obtained a separate grant in the Shenandoah Valley for 100,000 acres on October 31, 1731. Hite had been born at Bonfeld in Kraichgau region, north of Stuttgart, Germany. He was one of 13,000 Protestants who migrated to England in 1709 with the encouragement of Queen Anne. He was part of a second migration of 2,500 to New York in 1710. English officials planned to settle them in the backcountry. Ideally, the new colonists would produce naval stores to pay the costs of transporting them across the Atlantic Ocean and creating the new settlement.

New York colonial governor Gov. Robert Hunter was directed to place the new colonists on the western edge of existing English and Dutch settlements. They were to become a buffer against the French, who might cross the St. Lawrence River and begin to occupy lands claimed by New York.

The new immigrants were not skilled in producing naval stores such as masts, rope, and pitch. Their settlement in New York failed and Jost Hite moved to Perkiomen Creek, Pennsylvania. From there, he and his partner Robert McKay acquired their own land order for a large chunk of Virginia's backcountry from the colonial officials in Williamsburg.

Similar to Lord Fairfax, Hite and McKay negotiated no deal with Native Americans to extinguish their claims to the land. Officials from multiple colonies resolved Native American land rights to the Shenandoah Valley in the Treaty of Lancaster in 1744. The colonists gradually displaced the Monacan, Manahoacs, Tutelo, Shawnee, Delaware, Iroquois, Cherokee, and other groups who might have asserted land rights.

Following the colonial government's formula, Hite and McKay were entitled to 1,000 acres for each settler. The first ones erected single-room log cabins, with each side 16-20 feet long. Clapboard roofs were held in place by weight poles, while floors were dirt or split puncheons smoothed with broadaxe. Settlers also built stone houses using local limestone, some roofed with thatch. Crops included all the grains: wheat (including spelt and buckwheat), rye, barley, corn, oats, flax, and hemp. Livestock included cattle, pigs, sheep, horses.

Hite and McKay sent agents to Pennsylvania and New York to recruit both German and Scotch-Irish immigrants. The new settlers married within their separate cultural groups, even though they established farms that were intermixed rather than segregated. The only intermarriage between the two separate groups of early settlers failed and the couple separated.7

The Van Meter brothers and Jost Hite were aware of Lord Fairfax's assertion that he owned the entire lower Shenandoah Valley. In 1729 Robert Carter granted Mann Page 50,000 acres east of the Shenandoah River. Processing that sale through Lord Fairfax's land office, rather than in the colony's land office in Williamsburg, made clear that - from Lord Fairfax's perspective - the proprietary grant applied to the Shenandoah Valley.

Fairfax's claim to lands west of the Blue Ridge was not accepted in Williamsburg. Governor Gooch and his Council followed the Van Meter grants with another issued in 1730 to Alexander Ross and Morgan Bryan for 100,000 acres west of the Opequon River.8

The Van Meters and Hite gambled that the royal government in Williamsburg had the authority to issue patents (land deeds) in the Shenandoah Valley. Lord Fairfax's prices for parcels greater than 600 acres were 10 shillings for 100 acres, equal to the cost of treasury rights sold by the colony. Governor Gooch and the Council sacrificed the revenue that would have been gained if the land had been sold via treasury right and gave acres away to the Van Meters and Hite. That demonstrated Williamsburg officials set a higher priority on creating a buffer zone of loyal citizens to provide military defense compared to obtaining revenue.9

To eliminate confusion and to eliminate competition with settlers surveying lands based on the previous Van Meter grants, on on August 5, 1731 Hite purchased the rights of the Van Meters. He acquired all remaining unpatented parcels within the 40,000 acre grant to the Van Meter brothers. In 1734, the Van Meters sold Hite the land that they had previously patented for themselves, except for some parcels near Shepherdstown where John Van Meter lived. Hite may have been John Van Meter's cousin or nephew, a relationship that could have facilitated their dealings.10

Hite had personally migrated to the Shenandoah Valley in 1731. Local tradition holds that he brought 16 German and Scotch-Irish families in the initial settlement caravan. They lived near the Pack Horse Ford crossing over the Potomac River, until completing their houses further south on Opequon Creek.

Hite' first home was a classic German House, a Flurkuchenhaus (Ernhaus) where a door led directly into Kuche (kitchen) before guests went into Stube. Hite was part of the Opequon Settlement. Peter Stephens settled further south, where he initiated what would develop into Stephens City.

At the time, there were no roads crossing the Blue Ridge. Travelers on foot had passed through mountain gaps for perhaps 15,000 years, while colonial explorers using horses had crossed the mountains since John Lederer in 1670. However, it took two decades after first permanent colonial settlers arrived in the Shenandoah Valley before the old trails were improved enough for wagons to make a reliable crossing over the mountains to the Piedmont.11

Gov. Gooch gave the Van Meter brothers only two years to qualify for their grants, reflecting an urgency that may have been driven as much by competition with Lord Fairfax as the threat from the French or Native Americans. Hite had friendly relations with the Iroquois, Delaware, and others who travelled west of the Blue Ridge. His grandson said:12

Hite eliminated any possible competition from the Van Meter brothers for land between Opequon Creek and Shenandoah River by purchasing their grant, but the greater threat to his claim came from Thomas, Sixth Lord Fairfax.

Lord Fairfax had inherited the Northern Neck proprietary grant awarded initially in 1649 by Charles II to seven allies. Charles II was in France, trying to return to England as king, and gave away land in Virginia as a reward to his supporters. The rights to that land were protected by Lord Culpeper, with confirmation of the grant by King James II in 1688 and by King William III in 1693. Lord Fairfax acquired his control over 5/6ths of the grant by inheritance from his father and the remaining 1/6th by inheritance from his grandmother; he won the genetic lottery.

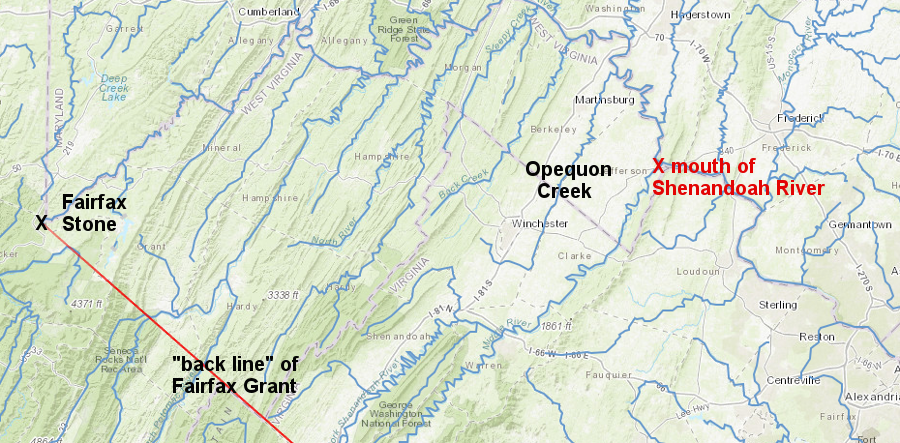

The Fairfax Grant, as it became known, included all the lands between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers to their "headsprings." In 1649, Charles II had no idea where the headsprings were located. By the 1730's, it was still not obvious if the Potomac River started at the Fall Line, at the confluence with another stream east of the Blue Ridge, or west of the Blue Ridge. Fixing the location of the headsprings would determine if the Fairfax Grant included the lower Shenandoah Valley and other territory west of the mountains.

If the headspring of the Potomac River was Great Falls and the river upstream of that point was defined to be the Cohongarooton, then the western edge of Fairfax's grant would not include any part of modern Loudoun County. His lands would be limited to the eastern Piedmont and the Coastal Plain. However, if the Potomac River's starting point was defined to be the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, Lord Fairfax would own the land west of the Blue Ridge - but west of the Shenandoah River, the colony would own all the land stretching "from sea to sea," at least according to Virginia's 1609 Second Charter.

the Fairfax Stone marks the headspring of the Potomac River as defined by the Privy Council in 1745, so Hite's land was within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lord Fairfax inherited the land grant while he was still a child, so his mother had control until she died in 1719. Thoms, 6th Lord Fairfax, was only peripherally involved in managing his Virginia lands for a dozen years after her death.

He became more personally engaged in getting cash from his land grant starting in 1732. The death of Robert Carter that year revealed how much wealth the land agent for the proprietary had accumulated during the last 10 years. From the perspective of Lord Fairfax, the wrong people - his employees - were making the most money from the grant. Rather than hire a new land agent from among the gentry living in Virginia after the death of Robert Carter, Lord Fairfax sent his cousin William Fairfax to be his real estate salesperson and land manager in Virginia.

He also established tighter legal rights to his massive land grant. In 1733, Lord Fairfax got an order from the Privy Council in London that blocked the Virginia colony from issuing new land grants within the area he claimed. That claim stretched from the Blue Ridge across the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley, west to the presumed location of the headspring of the Potomac River.

To define the boundary of land where the colony was entitled to sell parcels vs. land within the Fairfax grant, Lord Fairfax arranged for the Privy Council in London to order an official survey of the Northern Neck proprietary's boundaries.

Completing the actual survey would require three more years. The survey ordered by the Privy Council was done in 1736. It was completed by commissioners and surveyors hired by the two sides. The disputed interpretation of that survey would not be resolved for another nine years.

If the colony's interpretation was correct, Hite's 140,000 acres west of the south branch and main stem of the Shenandoah River could be patented without any challenge by Lord Fairfax.

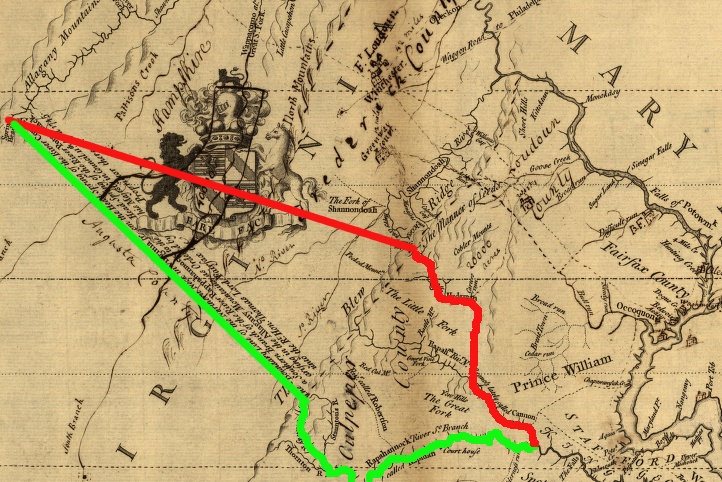

Not surprisingly, the survey resulted in competing maps defining the boundaries. The colony's map highlighted the success of Governor Gooch in stimulating settlement west of the Blue Ridge, through his grants of land to white Protestants such as the immigrants brought by Hite. Lord Fairfax countered by hiring the surveyor in King George County, John Warner, to produce an alternative map based on Fairfax's interpretation of the boundaries.

The colony and Lord Fairfax disputed the interpretation of the survey until a final Privy Council ruling in 1745. The Privy Council in London was more sympathetic to English gentry than Virginia gentry. It adopted the map generated by John Warner for Lord Fairfax, and granted him all the land west of the Blue Ridge that he requested.13

William Mayo's survey, done for the colonial government, highlighted settlement based on the governor's grant

Source: Public Record Office (UK), A Map of the Northern Neck in Virginia, the Territory of Right Hon Thomas, Lord Fairfax situate between the Rivers Patomack and Rappahanock according to a late survey (William Mayo, 1737)

Virginia proposed the red line, Fairfax proposed the green line so his grant would include the land between Rappahannock-Rapidan rivers

Source: Library of Congress, A survey of the northern neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the Rt. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the Bay of Chesapoyocke and between the rivers

Rappahannock and Potowmack:With the courses of the rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia, as surveyed according to order in the years 1736 & 1737

By 1734, before completion of the survey ordered by the Privy Council, the Secretary of the Virginia colony processed surveys covering 42,289 acres for the Van Meter grant acquired by Hite. Colonial officials decided Hite had recruited a sufficient number of settlers to be entitled to the 100,000 acre grant as well. The parcels originally had to be surveyed by the end of 1735, but the Council granted a two-year extension amd set a new deadline at the end of 1738.

Hite's land sales were profitable. He charged 3 pounds/100 acres, which was six times the 10 shillings/100 acres that Fairfax would have charged the settlers. He managed to sell to some settlers who had arrived on their own initiative, settlers who could have chosen to purchase from Lord Fairfax.

One reason they purchased from Hite was because he gave his buyers a commitment (bond) that his title to their land would be validated if challenged by Lord Fairfax, colonial officials, or others with land claims in the area. He also allowed his customers to survey the most-productive lands, bending property lines however they wished to include springs and bottomlands while excluding low-value acres with low soil fertility.

The colonial governor and Council probably expected their land orders to the Van Meters, Hite, and McKay to be converted into grants of large, contiguous blocks of land as was done by William Beverley, Benjamin Borden, Alexander Ross and Morgan Bryan. With the large land orders:14

Lord Fairfax came in person to Virginia in 1735-37. From his perspective, colonial officials had no authority to dispose of land to people like Hite within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant. Lord Fairfax considered Hite and those who purchased land from him to be trespassing squatters. So were others who received large or minor land grants from the colonial government in Williamsburg. Titles were unclear. Those who did not buy land from Lord Fairfax's personal land agent risked lawsuits forcing their "ejectment" (eviction).

In 1736, Lord Fairfax personally notified the governor and Council that he objected to the colony issuing any land orders or patents for property within the Northern Neck proprietary grant boundaries. The "caveat" entered by Lord Fairfax was intended to prevent the colony from issuing a patent (land deed) which would officially transfer title of a parcel.15

Within the exterior boundaries of the Van Meter and Hite/McKay land orders defined by the Shenandoah, Opequon, and Potomac rivers, the first settlers selected small parcels of high-quality land. The business practices of Hite and McKay were informal and "customer friendly;" they allowed land purchasers to direct the surveyors. Purchasers told surveyors to shape boundaries to maximize the acreage of high-quality land. Later purchasers would have to select parcels without springs for watering livestock, or flat river terraces with rich alluvial soil for growing crops.

The first Opequon settlers emphasized productive use of land, not hoarding it for speculation. Their attitude was that the first settlers to clear land in an area were entitled to pick the best acreage, and were entitled to as much land as a family could actually use (including woodlot) but no more. Hite and McKay had attracted the yeoman farmers Governor Gooch wanted to block the French from occupying valleys west of Blue Ridge.

Settlers thought the risks they were taking entitled them to relaxation of the requirement that property boundaries align next to each other and be somewhat rectangular. settlers attitude was that they were entitled to just as much land as a family could actually use, including woodlot, but the first to occupy and area were entitled to pick the best acreage. Metes and bounds surveys separated springs, streams, and rich bottomlands underlain by limestone bedrock from less-valuable hills underlain by shale.

There were few surveyors available to work west of the Blue Ridge, and all official plats had to be signed by a surveyor licensed by the county. No county courts managed activities west of the Blue Ridge until 1735, when Orange County was established. Spotsylvania County surveyor George Hume refused to work west of the mountains, so Governor Gooch appointed Robert Brooke as a special surveyor. Brooke was surveyor for Essex County, far to the east, but was searching for land for himself.

Brooke and his successors allowed land claimants great flexibility in defining boundaries, and that approach made them popular with land claimants. Brooke stopped surveying in 1738 only after the Orange County surveyor complained about his practices.16

until Orange County was created at the start of 1735, no county surveyor had official responsibility for the land claimed by Jost Hite and others west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The survey pattern became a major issue between Jost Hite and Lord Fairfax. Lord Fairfax visited Hite in person during his 1735-37 stay in Virginia. Fairfax said he would allow settlers who had purchased from Hite to stay on their property, and he would not issue grants for already-occupied lands. However, Fairfax warned that more-rectangular surveys would be required before he would issue grants and provide his version of title; Lord Fairfax did not want to end up with low-quality land in scattered fragments that would be hard to sell.

Irregular surveys based on metes and bounds descriptions were a Virginia tradition. The only exception was for lots that were surveyed and sold in a new town, such as Alexandria. Town lots were surveyed before sale, and customers bought parcels with pre-defined rectangular or square boundaries. James Wood created rectangular parcels in 1743 when he surveyed the land that became the county seat, after Frederick County was created by the General Assembly in 1743. What Wood called Frederick Town was renamed Winchester in 1752.

Outside of towns, early settlers could carve a 300-500 acre farm out of the wilderness by defining a parcel from whatever lands were unclaimed, then settle there and make a preemption claim. When settlers had sold a few crops and accumulated enough cash to pay for the official land transfer process, they would purchase a headright or treasury right and have their parcel surveyed.

Typically county surveyors required parcels to be no more than three times as long as they were wide, but new parcels did not have to align with any others in the area. Gaps could be left between surveys, with that land to be sold at some later time to some later buyer.

Surveyors could create parcels that enclosed high-quality soils for farming and rich hardwood forests for woodlots, while excluding less-productive hillsides. Though the length of a parcel was supposed to be no more than three times the width, the polygons defining such parcels did not have to be rectangular or even have a single right angle.

Some of Hite's customers came to Fairfax, willing to pay him as well to confirm their land ownership. Fairfax forced resurveys before issuing patents to parcels based on a more rectangular pattern. The grid-like surveys ensured that all the land would be incorporated into parcels that could be sold; no slices of isolated, low-value land would be left as unsaleable tracts.

Fairfax complained that under Hite's approach:17

In 1745, the Privy Council in England upheld Fairfax's definition of the grant's boundaries. It ruled that Lord Fairfax owned the lower Shenandoah Valley where the colony had awarded 140,000 acres to Van Meter, Hite, and McKay plus additional large tracts to other claimants.

The Privy Council directed Lord Fairfax to relinquish his claims to parcels which had been purchased from Hite's, if the survey had been completed by the end of 1737. Hite withdrew the surveys and associated fees he had filed at the Secretary's office in Williamsburg and re-filed them with Lord Fairfax.

Fairfax returned to Virginia in 1747 and issued new grants to settlers who had bought land from Hite. He required the pre-existing landowners to accept resurveys that complied with 3:1 ratio of width to length, and did not incorporate all the springs and streams in their area. Lord Fairfax was also supposed to issue clear title to settlers who had agreed to purchase land from Hite, but whose paperwork had been delayed until the Privy Council reached a final decision.

In their negotiations, Hite and Fairfax agreed that Fairfax would confirm the grants issued by Hite and those landowners would then pay their annual quitrents to Fairfax. However, Fairfax maintained his caveat and blocked finalization of land transfers.

Fairfax collected quitrents but failed to transfer official title to Hite's buyers. He recognized that the best lands in the Shenandoah Valley had been "high graded" by the first settlers.

The colony's Secretary did not act on surveys filed by Brooke and others in Williamsburg. Hite's purchasers could not obtain clear title, and Lord Fairfax's objections forced Hite to maintain a bond guaranteeing clear title to his buyers. That cost Hite money and constrained his credit.

On October 10, 1749, Hite and McKay filed suit to force Lord Fairfax to grant title without requiring resurveys. The Joist Hite et als. v. Fairfax chancery lawsuit would cloud land ownership for over 35 years. James Wood, surveyor for Orange County and then clerk of the court for Frederick County, marked boundaries of properties that became the town of Winchester but purchasers could not obtain clear title for even his rectangular lots.

Still, the investment in land by the Hite's was a model for George Washington. He wrote a neighbor in 1767 that he would not loan him additional money. Instead, Washington recommended that the neighbor sell his property, pay his debts, and invest his remaining money in land along the Monongahela River.18

The General Court in Williamsburg ruled in favor of Hite and his buyers in 1771, but Lord Fairfax still continued legal proceedings. He had won in the Privy Council 25 years earlier, and was not willing to accept the judgment of a colonial court.

By 1786, the Fairfax side of the lawsuit was at a disadvantage. Lord Fairfax had died. Denny Martin, his nephew and inheritor who renamed himself Denny Fairfax, was living in England. The Joist Hite et als. v. Fairfax lawsuit was to be decided by a Virginia court after the American Revolution, and no Privy Council influence could shape the decision.

The Supreme Court of Virginia ruled on May 8, 1786 that the Privy Council ruling was not valid. The Virginia court decided that Hite was entitled to his 140,000 acres. His purchasers and their descendants received clear title to their land.

Almost all of the Fairfax Grant lands that had not been sold already were transferred to the Commonwealth of Virginia, based on the state's claim that the lands had been forfeited to the state upon the death of Lord Fairfax. Lawsuits continued for 140,000 acres that Denny Martin/Fairfax claimed he had obtained. John Marshall led the legal team that contended the Commonwealth of Virginia was not authorized to seize Lord Fairfax's land during the Revolutionary War. Marshall acquired the right to purchase the 140,000 acres at a steep discount, assuming he would convince the state courts that Denny Fairfax was the rightful owner.

As the legal cases wound through the courts, the state sold all of the other, not-yet-claimed land within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant and kept the revenue. Marshall finally won the case. In the end, people who had purchased land from Virginia officials within the Fairfax Grant boundaries got clear title, except for within the 140,000 acres. Purchasers there had to pay Marshall in order to get clear title to the property which they thought was already theirs.19

the Governor of Virginia (Patrick Henry) was able to sell land near Winchester in 1789, since Virginia had seized the remainder of the Fairfax Grant

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Land Office Patents and

Grants/Northern Neck Grants and Surveys