Virginians feared the French would assert their claim to Louisiana by establishing trading posts on the Ohio River and supplying Native Americans

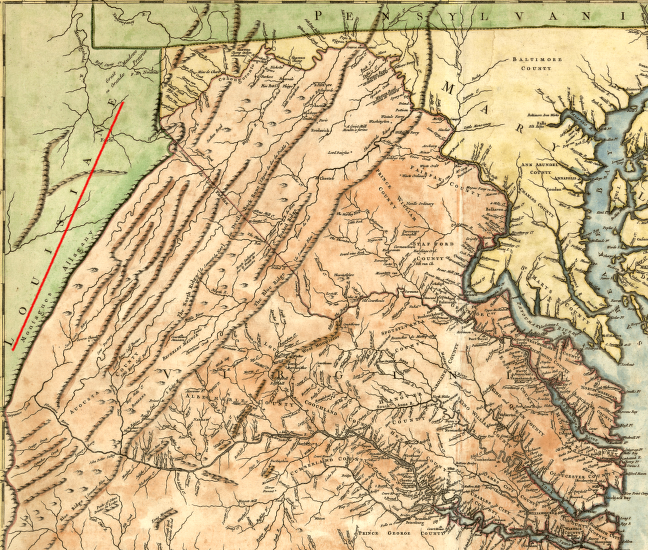

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Virginie et du Maryland (1757)

Virginians feared the French would assert their claim to Louisiana by establishing trading posts on the Ohio River and supplying Native Americans

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la Virginie et du Maryland (1757)

Even after General Braddock was defeated near modern-day Pittsburg, the English colonists east of the Blue Ridge were safe from attack. It was the settlers living west of the Blue Ridge that were attacked by the hostile Shawnee, Cherokee, and other Native Americans. As Gov. Spotswood had anticipated 50 years earlier, colonists in the valleys of the Shenandoah, James, Roanoke, and New rivers provided a buffer that blocked French and Native American attackers from reaching the Piedmont.

Since the 1720's, Virginia policy had encouraged German and Scotch-Irish immigrants as well as English-speaking settlers to occupy the land west of the Blue Ridge:1

Presbyterians who had migrated in stages from Scotland into Ireland, and then to America, walked south from Pennsylvania down the "Great Road" (now Route 11/I-81). They crossed the Potomac River and built small farms on the borderlands. Major land grants were issued to William Beverly, Benjamin Borden, and James Patton to recruit the Scotch-Irish. Virginia officials ignored the nonconformist religion of the new immigrants, and Presbyterians dominated the vestries of some Anglican parishes west of the Blue Ridge.2

Immigrants with German heritage ("Deutsch" was modified into "Pennsylvania Dutch") moved into the New River Valley in the 1740's. The pietist religious practices of the German immigrants led to one community being called Dunkards Bottom (now covered by Claytor Lake), while Hans Meadow later grew into Christiansburg. Other German-speaking immigrants settled on the watershed divide between Toms Creek and Stroubles Creek, in the area known today as Prices Fork in modern Montgomery County.

Virginia landowners eager to sell land west of the Blue Ridge recruited German pietists from Ephrata, though their religion made them reluctant to join the militia

Native Americans did not welcome these new settlements. By the 1730's there were almost no Native American towns remaining in the valleys between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains. The valleys had become traditional travel routes for Iroquois, Cherokee, and Catawba to raid each other, and were valued hunting territory for the Shawnee as well.

The Iroquois abandoned their claim to those lands in the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster, but the Shawnee were not a party to that treaty. In the 1750's, they still objected to the intrusion of colonists into territory they still claimed south of the Ohio River. In 1749, soon after settlers moved into the New River Valley, Shawnee seized furs from the home of Adam Harman.3

Even before Braddock's defeat on July 9, 1755, the Shawnee took advantage of their alliance with the French and raided farms and isolated settlements far south into Virginia.

The Shawnee implemented a reign of terror, and it succeeded initially. The goal was to drive the English, German, and Scotch-Irish eastward, pushing them back from their recent occupation of Native American lands. Hundreds of colonists were killed or captured. Women and children were carried back to Ohio and Kentucky to help repopulate Shawnee communities. Colonial settlements located deep in the borderlands, such the valleys of the Greenbrier River and the South Branch of the Potomac River, were abandoned.

In one famous incident, the Shawnee may have targeted Col. James Patton. He was visiting the New River Valley to examine his substantial land claims. Patton stayed in a cabin at Draper's Meadows on Stroubles Creek, near the modern Duck Pond on the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg.

On July 8, 1755, one day before Braddock's forces near Fort Duquesne were defeated, Patton and several others were killed in a swift attack. During the raid, Philip Barger was decapitated. His head was displayed when the raiders visited another cabin, indicating the raid was designed to create terror on the frontier as well as perhaps demonstrate that top colonial leaders were vulnerable.

Mary Draper Ingles was captured in the "Draper's Meadows Massacre." Her escape and extraordinary long walk back home from the Ohio River have been commemorated in various books. An outdoor drama, "The Long Way Home," presented her story on a stage at the Ingles farm from 1971-1999. It was rewritten and revived in 2017 as "Walk to Freedom - The Mary Draper Ingles Story."4

monument on Virginia Tech campus for victims of the Shawnee attack, including Col. James Patton, on July 8, 1755

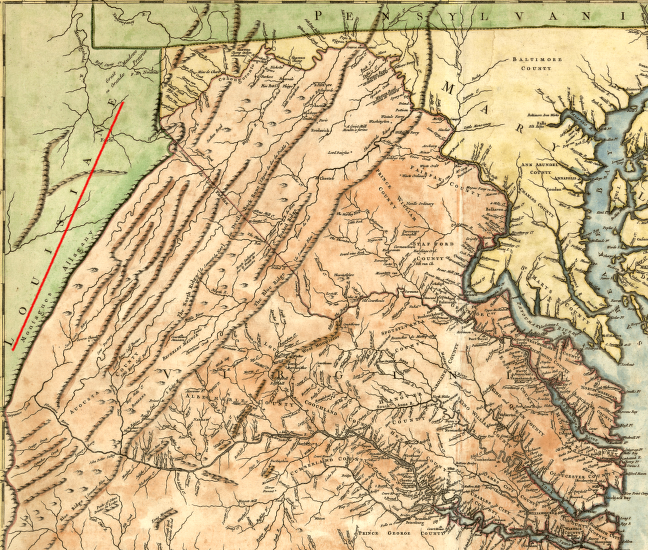

James Burk was forced to flee his mountain valley home in modern-day Tazewell County in 1756, during another Shawnee raid. He joined up with Andrew Lewis and the Sandy Creek Expedition, which marched through "Burk's Choice" as the settlers tried to go on the offensive and attack Shawnee towns close to the Ohio River.

The soldiers reportedly enjoyed potatoes that Burk had planted and the valley has been known since as Burke's Garden, but the Sandy Creek Expedition was unable to penetrate through the mountains during the winter. The men returned in failure, without ever fighting the Shawnee.

Burk waited until 1763 to move back to his valley. After only 10 days, he decided that the frontier was still unsafe and fled again.5

Burke's Garden was one of the colonial farming sites abandoned under pressure from Shawnee during the French and Indian War

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Shenandoah Valley, Rev. John Rhodes miscalculated when it was safe to return. He had moved into the valley in 1748, fled a decade later, and then returned in 1764 to near modern-day Luray. That year, he and some of his family died in what was perhaps the last attack in the region.6

After General Braddock's defeat, the remnants of the two British regiments that had arrived in Virginia retreated into Pennsylvania. That left the Virginia settlements unprotected. Local residents created fortified houses to resist attack, and Virginia (along with Maryland and Pennsylvania) built a series of forts on the western frontier where residents could seek safety.

in the Shenandoah Valley near Dayton, Daniel Harrison constructed a stone house that offered protection against attack

Source: Fort Harrison, The Daniel Harrison House

Governor Dinwiddie commissioned George Washington as Colonel of the Virginia Regiment, and his orders included:7

However, the political requirement to fortify a line along the western edge of settlements trumped Washington's objections to such a futile investment of scarce resources. Washington placed his headquarters in Winchester, then visited the forts - some of which were poorly sited, poorly constructed, or both - all the way down into the New River Valley.

Washington had great difficulty in recruiting/forcing soldiers to serve in the Virginia Regiment, in retaining them, and in supplying them. He also had to deal with a sense of defeatism among the colonists exposed to attack:8

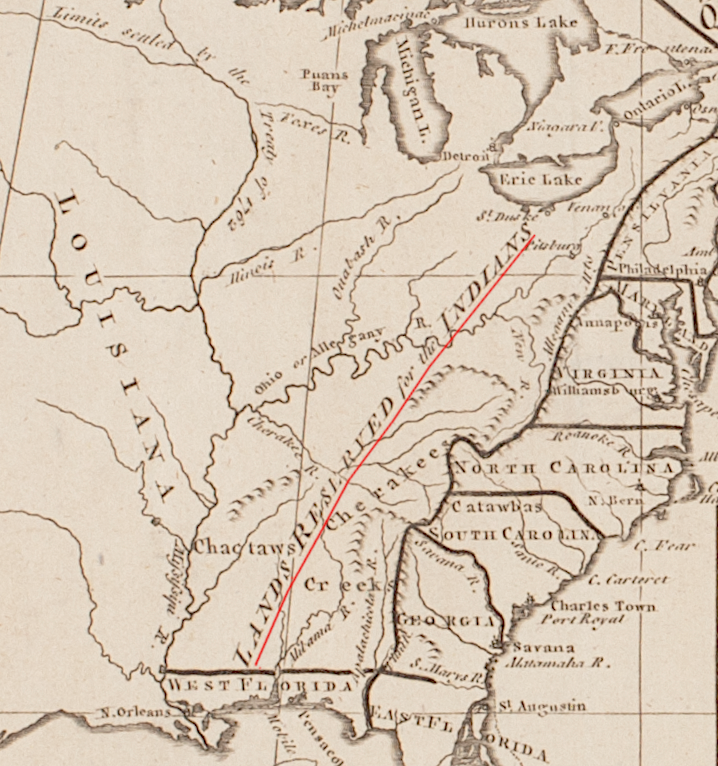

New British forces were sent to North America, though not to Virginia. The English captured Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760. In the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the French transferred to Spain their claims over New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River, and surrendered nearly all remaining claims in North America to England.

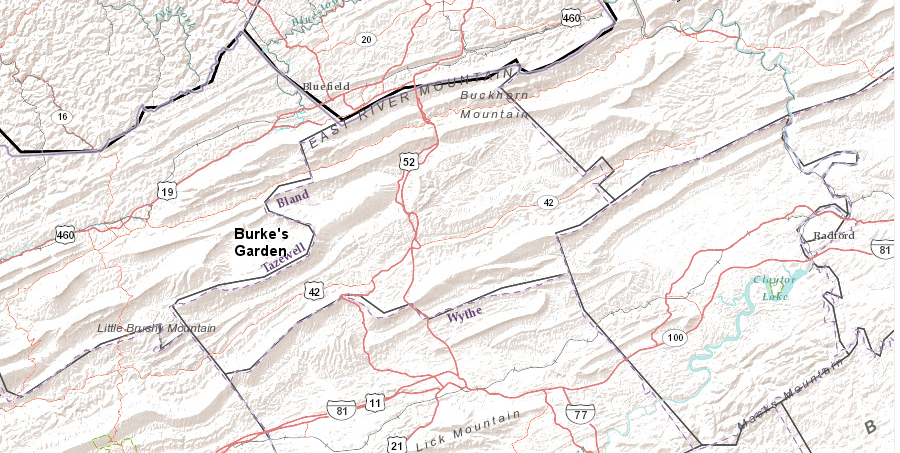

American colonists coveted the land acquired by Great Britain after the French and Indian War (tinted brown)

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of North America, shewing the advantages obtain'd therein to England by the peace (May, 1763)

Military victory over the French did not translate automatically into easy access to Ohio Valley lands for Virginia land speculators and settlers. Much to their dismay, the barrier of French and Native American fighting forces was replaced by a hard-to-defeat political mandate issued by officials in London.

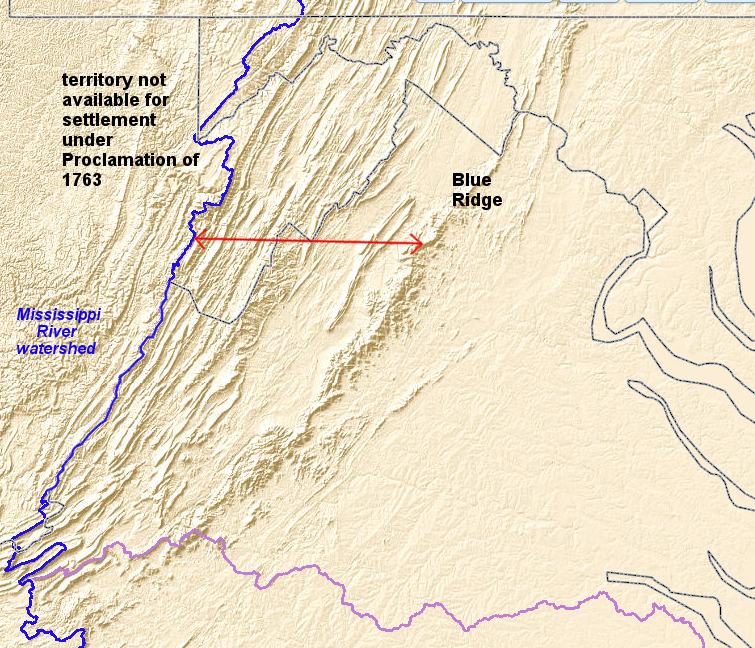

The Proclamation of 1763 banned settlement in the valleys of the Holston, New, Greenbrier, and Ohio rivers. No English settlement would be authorized in the Mississippi River watershed.

Minimizing the incursions of settlers into traditional Native American hunting territories would, at least in theory, minimize the need for British troops to stay in America and protect colonists from the "Indian" half of the French and Indian War.

The costs to fight that war had put Great Britain in debt. The Proclamation of 1763 was an early version of the smart growth approach to land use planning, to steer development in order to reduce the costs of government. Isolating the conflict-causing colonists from Native Americans was expected to reduce the military expenses required to protect colonists from Native American attack.

Stockholders in the Ohio Company, Loyal Land Company, and other syndicates were at risk of losing their great opportunity to "buy low, sell high" with western lands. Virginia officials, including governors appointed by the king, worked hard to overcome the limitation and re-open land speculation opportunities.

reserving lands for Native Americans was intended to minimize costs for British military forces stationed in the colonies

Source: American Antiquarian Society, The British governments in Nth. America: laid down agreeable to the proclamation of Octr. 7, 1763

The 1768 Treaty of Hard Labor, 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1770 Treaty of Lochaber, and 1774 Treaty of Camp Charlotte pushed the limit of settlement further west, but the 1774 Quebec Act made clear that officials in London would not allow the scale of land speculation desired by the Virginia gentry.

In addition to minimizing future military costs via the Proclamation of 1763, London officials also planned to recoup the costs of fighting the previous French and Indian War. Officials in London thought the North American colonist should pay their share of that military debt.

After all, the colonists were the primary beneficiaries of the elimination of the French threat. An expensive surge of British military forces had been sent across the Atlantic Ocean and those forces had created greater security for settlers on the western edge of the colonies. The Proclamation of 1763 limited land speculation in the Ohio River valley and elsewhere, but from Luray to the South Branch of the Potomac River (a distance of 60 miles) the threat of attack had been reduced.

the French and Indian War made 60 miles of backcountry (shown by red line), from the Blue Ridge to the boundary line established by the Proclamation of 1763, safer for settlement

Source: US Geological Survey, The National Map

Someone had to pay the costs of making the western borderlands safer for colonists. As modifications of the Proclamation of 1763 through various treaties opened up a vast expanse of lands along the Ohio River, west to the mouth of the Kentucky River, the benefits of the war to the colonists were even more clear to British officials.

Colonists in America did not share that perspective. The Stamp Act of 1765 stirred up complaints that Parliament lacked authority to tax colonists directly. In response, Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend created new import duties, including a tax on tea.

In Virginia and other colonies, the new taxes imposed by Great Britain in the 1760's to pay the costs of the French and Indian War triggered a series of confrontations. The land speculators who had invested in the Ohio Company and the Loyal Land Company were especially forceful in their opposition to paying for the costs of the war that created the opportunity to occupy the western lands. Boycotts against British goods ("non-importation agreements") strained relations and helped define a distinctive American identity.

The ultimate impact of the French and Indian War on settlement west of the Blue Ridge was a revolution that ended British control of its colonies in North America. The land speculators had to sacrifice their hopes and Virginia ceded its claims to lands north and west of the Ohio River, in order to strengthen the new United States.