Looking Westward From the Shenandoah Valley

Virginia stretched to the Ohio river before 1863, but Tidewater-focused leaders failed to build adequate transportation infrastructure west of the Allegheny Front

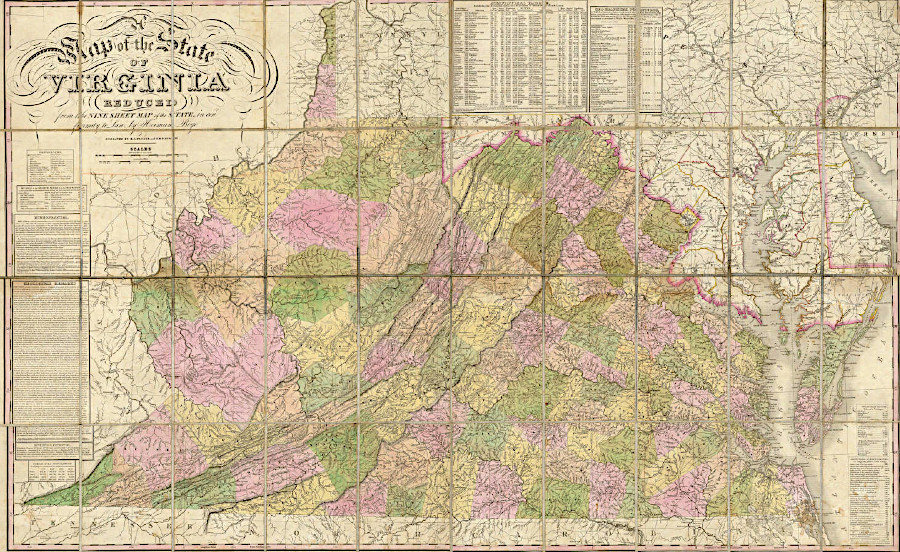

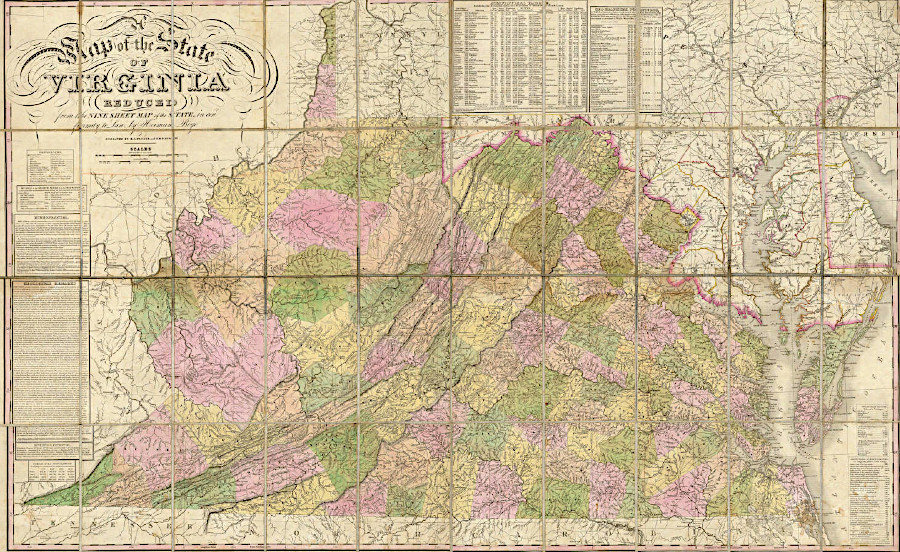

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, A Map of the State of Virginia (by Herman Boye, 1827)

The failure to create successful transportation corridors to the west led to the truncation of the western third of Virginia, and the creation of a separate state

with a different economic and political orientation from the Shenandoah Valley.

Travel west was less important to the farmers in the Shenandoah Valley, because the demand for their products was substantially less in that direction. The initial European settlers of the valley shipped their crop and livestock north to Philadelphia along the Great Wagon Road and to Baltimore, and to the east across the Blue Ridge mountains.

There was minimal trade to the west. Local demand from the thin population of the western counties was small. Merchants at the Atlantic ports (able to ship easily to the large populations of Europe, the Caribbean, and South America) offered higher prices than merchants on the Ohio River.

Roads across the Allegheny Front were expensive to build. Prior to the Civil War, the Board of Public Works invested in few "internal improvements" to facilitate travel west of the Shenandoah Valley. Tidewater planters and merchants in the Fall Line cities were not interested in simulating trade towards the Ohio. From the days of Governor Spotswood and later George Washington, their objective had been to draw trade from the Ohio River to the Atlantic Coast.

There were relatively few times, such as the 1788 convention to ratify the Constitution and the 1851 state constitutional convention, when the western settlers were able to force consideration of their demands for improved transportation in the Ohio Rive drainage. Settlers in Kentucky, west of the Eastern Continental Divide, shipped their deerskins, corn, wheat, timber, and other products down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans. Due to the economics of such trade and the distance from Richmond, Virginia's leaders supported admitting Kentucky as a separate state into the Union in 1792.

The Civil War created the opportunity for the remaining disaffected Virginians west of the Allegheny Front to escape the political control of those living east of the Blue Ridge. In 1863, the Confederate government in Richmond was unable to block the admission of West Virginia as a new state.

Farmers raising corn or cattle or tobacco in Augusta County in 1850 traveled by wagons and drove livestock on the relatively well-maintained roads to Richmond or Alexandria. Farmers in Rockbridge County could carry move products a short distance by wagon to boats at Lexington and ship agricultural products via the James River and Kanawha Canal to Richmond.

Only a few western Virginians, such as the manufacturers of cast iron products at the charcoal-fueled furnaces, found it economic to haul products over poor roads to those living in the western valleys or to the Ohio River. After such a trip, the producers and the buyers probably talked about the failure of the state government to build better roads or the promised canal down the Kanawha River.

Virginia and Pennsylvania provided an interesting contrast. Pennsylvania faced open rebellion by its western settlers in the 1790's, after an eastern-dominated legislature imposed a

heavy tax on whiskey - a product made primarily in the under-represented western counties.

George Washington had to risk his personal reputation yet again to establish a national union, when he agreed to lead the Federal forces that President Adams mobilized to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion. Washington was a nationalist more than a Tidewater Virginian. Unlike so many in the Virginia General Assembly and the Congress between 1776 and 1861, Washington had a clear understanding of the compromises and investments required to build a nation. He knew first-hand the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, and how barriers to commerce that threatened the economic potential of all regions could be overcome with transportation improvements.

In the next 50 years after the Whiskey Rebellion, Pennsylvania integrated its western counties with the eastern ports through transportation improvements such as the Main ine Canal. By the time of the Civil War, the political differences between the eastern (Atlantic Ocean) and western (Ohio River) counties of Pennsylvania were small compared to the sectionalism between the equivalent areas in Virginia. After Kentucky became a separate state following ratification of the US Constitution, eastern Virginians refused to compromise sufficiently on political representation and taxation policies, or to finance the internal improvements required to bind the remaining western counties together with those east of North Mountain.

Starting in 1861, Yankee armies invaded Virginia several times from the western region during the Civil War. The transportation constraints (and effective fighting by Stonewall Jackson's "foot cavalry") limited the Union successes. These invasions were relatively minor incursions, intended to divert Confederate reinforcements or to interdict supplies. The Union Army goa was to capture Richmond rather than to seize acres west of the Blue Ridge.

The boundary of West Virginia was drawn in 1863 where transportation patterns changed. The new state did not include counties like Alleghany or Rockbridge further to the east. If the Confederacy was able to establish its independence, the Virginia/West Virginia boundary would become a new national border to defend.

After West Virginia became a separate state, northern capitalists like William G. Davis and Henry Elkins built railroads into the interior of the new state. These railroads connected to the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad, not to railroads leading into Virginia. As a result, Baltimore and Pittsburgh rather than Lynchburg, Richmond and Alexandria benefitted from the initial extraction of the timber and coal wealth of the region west of the Shenandoah Valley.

After Collis B. Huntington built the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad to carry coal from southern West Virginia to Newport News, Staunton was connected by rail to the Ohio River. However, Clifton Forge became the main rail staging center east of the mountains for servicing the steam locomotives, equivalent to the role played by Roanoke for the Norfolk and Western Railroad.

Three counties on the far western edge of the valley - Highland, Bath, and Alleghany - are not blessed with limestone soils. The forests on these hillsides offered fuel for iron furnaces, but little opportunity for early settlers to accumulate wealth from agriculture. Tidewater planters did not acquire the hillsides in large tracts, and the area has never been densely settled.

Highland is the "Switzerland" of Virginia, with a strong effort to attract tourists to beds and breakfasts. It is the only county where over 10% of the residents are "farmers." On the hillsides of the region, the most valuable crops are apples and maple sugar, but hayfields are the most common sight.

Bath was named for the hot springs that were developed into recreational spas before the Civil War. In the days before air conditioning and modern science, it was considered healthy to "take the waters" at mountain resorts and avoid the heat of August in Tidewater ports.

Since summer was also the yellow fever and cholera season, there was some logic in this pattern. The wealthy would take a wagon to a resort, then travel on a circuit to visit other mountain results. The networking at the resorts by the gentry led to business deals, political alliances, and even marriages as well as recreation. It continues today with business

conferences at places like the Homestead Resort.

Alleghany County's population has typically been two to three times larger than the population in Highland and Bath counties. Alleghany County has more mineral resources, especially iron, together with the James River as a transportation corridor. The Forks of the James, where the Jackson and the Cowpasture rivers join, is just east of Clifton Forge.

Alleghany grew after the C&O railroad was built through it and connected Newport News with Huntington, West Virginia, facilitating coal exports. A pulp mill in Covington still is able to convert the forested hillsides to cash for the stockholders, as well as provide steady employment. The resorts in Bath and Highland are seasonal employers.

Links

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Regions of Virginia

Virginia Places