State Recognition of Native American Tribes in Virginia

chiefs of Virginia's state-recognized tribes with Gov. McDonnell (November 2012)

from L to R: Rappahannock Chief Anne Richardson, Nottoway Chief Lynette Lewis Allston, Upper Mattaponi Assistant Chief Frank Adams, Pamunkey Tribal Member Ashley Atkins, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Chief Walt Brown, Upper Mattaponi Chief Kenneth Adams, Governor McDonnell, Mattaponi Chief Carl Custalow, Patawomeck Chief Robert Green, Monacan Chief Sharon Bryant, Chickahominy Assistant Chief Wayne Adkins

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia's state recognition process is intended to acknowledge Native American tribes that preceded European colonization. There are few benefits from recognition beyond the symbolism of official acknowledgement, but gaining official status is considered a significant honor and can be used when marketing tribal events where visitors are welcomed.

State acknowledgement of a tribe is separate from the Federal process; the Commonwealth of Virginia has used different procedures and criteria for granting state recognition. Most Native American groups which existed in 1607 were disrupted by colonization and can not meet the criteria, but 11 organized groups have been officially recognized by either executive or legislative action in Virginia.

The state recognition process is supposed to distinguish groups that may choose to adopt an ancient culture vs. actual historical remnants of tribes that have remained in the state despite discrimination. The review of recognition requests is designed to screen out groups with a desire to manufacture a Native American identity, but without solid evidence to show long-term cultural and genetic heritage.

Documentation of historical links to the past is challenging, and state recognition of the last three tribes in 2010 created enough controversy to end the process. The tribes with official state recognition by 2024 were:

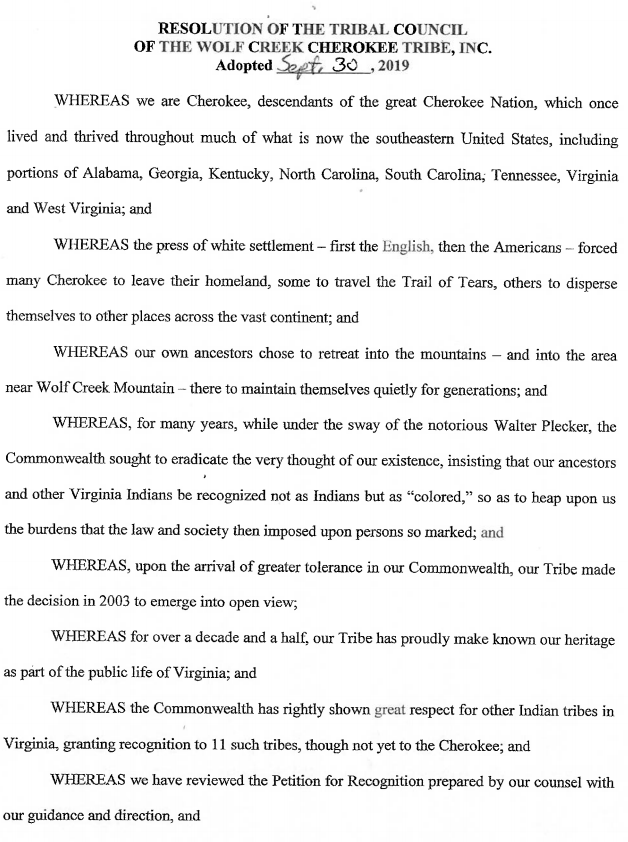

The Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe is now seeking to become #12. As its leader explained in 2019:1

- We want respect... Cherokee people were always here, there were more Cherokee people than any other people at one time. And we want respect for my family … and all the troubles we had in the past.

Three Cherokee tribes have Federal recognition, but none are located in Virginia. The Appalachian Cherokee Nation is a separate organized group that also claimed historical ties to the Cherokee who lived in Southwestern Virginia in the 1600's and 1700's. That group had requested recognition by the General Assembly in 2012 when it was based in Westmoreland County, but by 2019 the Appalachian Cherokee Nation was centered in Frederick County west of the Blue Ridge. The Appalachian Cherokee Nation and the United Cherokee Indian Tribe of Virginia, a separate group based in Amherst County, requested recognition by the General Assembly in 2012 but no action was taken. Pursuit of recognition by those two groups appeared dormant when the Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe initiated its request.

The Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe is named after a creek and mountain in Giles County, but the Wolf Creek Tribal Center and Museum is located in Henrico County. That area was occupied by Algonquian-speaking groups subordinate to Powhatan when the English arrived in 1607, and far from the traditional Cherokee territory in Southwest Virginia.

The Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe will have to show state officials sufficient documentation of its continued existence within Virginia, as well as provide other information, in order to receive state recognition. Clarifying the relationship of different claimants to Cherokee heritage will be part of the recognition process, though it is possible that more than one group could ultimately be recognized. The Wolf Creek group described itself in language that could be interpreted as including all Virginia-based Cherokee:2

- Members of the Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe, Inc. of Virginia are the Cherokee people of the Commonwealth of Virginia who have always occupied the state of Virginia and whose tribal members are dedicated to maintaining our Cherokee culture and heritage through ongoing education, preservation, and community outreach.

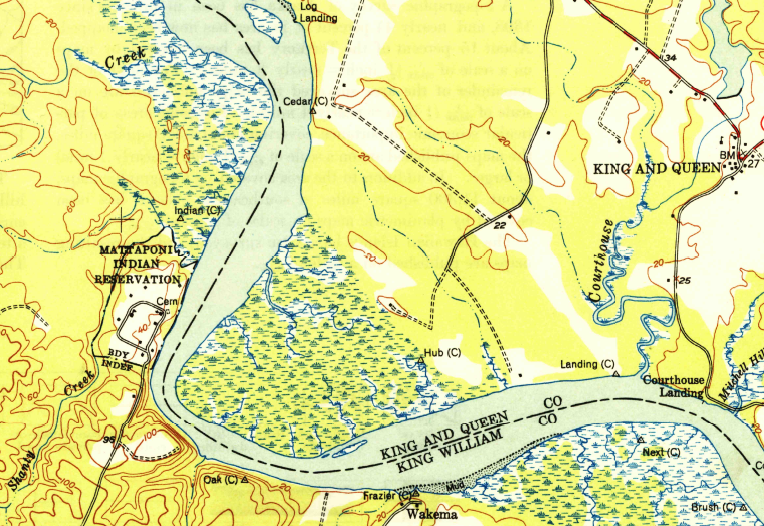

The Pamunkey tribe was one of the first in Virginia to receive state recognition, in treaties signed after the Third Anglo-Powhatan War ended in 1644 that established a state reservation which has existed ever since. The Pamunkey were also the first to obtain Federal recognition, through the administrative process of the US Department of the Interior, in 2016.

The Pamunkey are well known as a result of the popularity of the Pocahontas tale, but they are not the only Native American group in Virginia. The US Congress passed and President Trump signed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act in 2018. Through that legislative action, the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond tribes also received Federal recognition.

Four state-recognized tribes - the Mattaponi, Nottoway, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), and Patawomeck - do not have Federal recognition. The Mattaponi started to follow the same administrative process used by the Pamunkey, but the US Department of the Interior has not advanced their petition forward for a decision.

Virginia's elected members in the US Congress did not include the Nottoway, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), and Patawomeck in the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. It was first introduced in 2000, a decade before those three tribes received state recognition. The scope of the bill was not expanded to include the three tribes in the 18 years required to obtain passage, while the Pamunkey and Mattaponi were dropped to facilitate their efforts to use the administrative process in the Department of the Interior.3

In 2023, US Representatives Abigail Spanberger, Jennifer Kiggans, and Jennifer Wexton introduced H.R.5553. The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia Federal Recognition Act note the group was also known as the Potomac Tribe, Potomac Band, Patamacks, and White Oakers.

The bill would make the 2,500 members in Stafford and King George counties eligible for all services and benefits provided by the Federal Government to federally recognized Indian Tribes without to the existence of a reservation, such as assistance for housing, education and health care. No gaming activities would be authorized, however.

A member of Patawomeck Tribal Council, commenting about the challenge of generating the documentation required by the administrative process for obtaining Federal recognition, said:4

- Nobody "discovered" us because we were here already.

When the English first explored Virginia, they discovered that the paramount chiefdom controlled by Powhatan included over 30 tribes, one of which was the Pamunkey. The English soon dealt with other tribes outside of Powhatan's control, including the Patawomeck and Dogue (Taux) in Northern Virginia, plus the Monacans and Manahoacs west of the Fall Line.

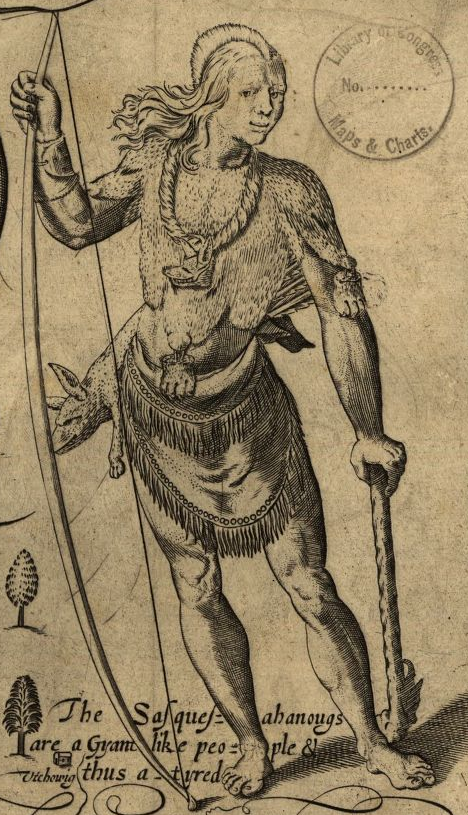

As explorations extended westward, colonists traded, fought, and negotiated with additional tribes such as the Tutelo, Saponi, Meherrin, Nottoway and Cherokee, plus Susquehannocks north of the Potomac River and Iroquois based in New York. Fur traders, government officials, and frontier settlers learned the distinctions between different groups in order to arrange for food, furs, land, and peace.

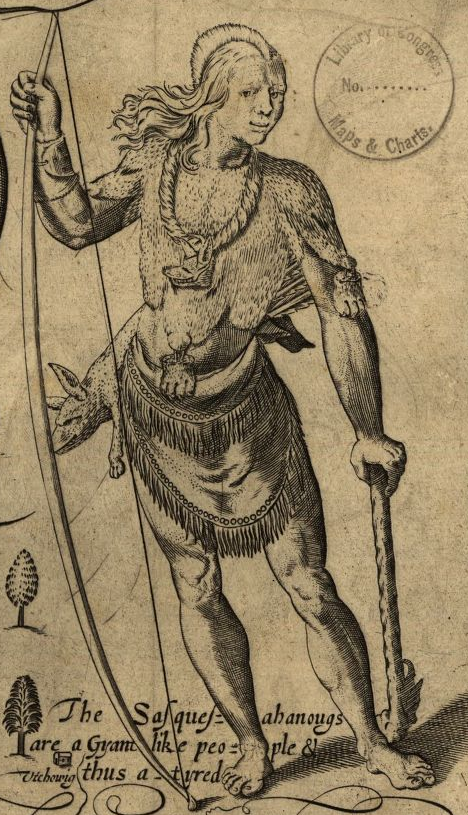

John Smith started the Virginia colonists' dealing with the Susquehannocks in 1608

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Formal treaties between the colonial government of Virginia and Native American tribes date from the 1600's. Those treaties were signed long before the American Revolution led to the creation of a Federal government that negotiated treaties with tribes. Ritual payments to the Virginia governor have been documented by photographers for the last century.

the wife of Governor Davis accepted the Chickahominy's annual payment in 1919, as required by the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Group Paying Annual Tribute of Game Animals to Governor's Wife (Non-Native) on Steps of Executive Mansion

In the 1700's, colonial officials in London asserted more-centralized control over Native American affairs, but still struggled to control trade between Native American groups and colonists.

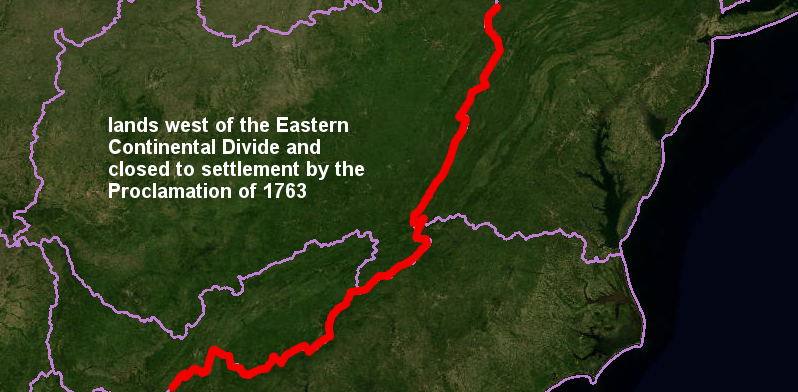

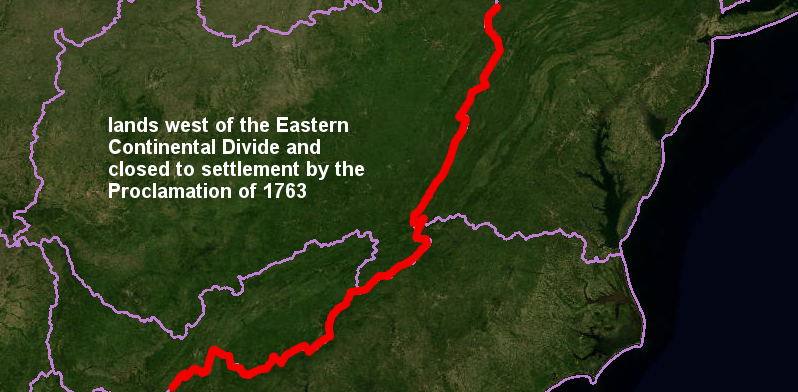

The Proclamation of 1763, issued by King George III after the French had ceded their North American claims, was a blunt tool intended to minimize expensive conflicts over land claims. The proclamation identified "Indian territory" and banned new settlement west of the Alleghenies, at least in theory.5

the Proclamation of 1763 defined a boundary blocking settlement (red line), based on the Eastern Continental Divide

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Hydrography Viewer

Since its creation in 1789 after ratification of the US Constitution, the Federal government of the United States has taken the role of the sovereign with exclusive responsibility to sign treaties with various tribes. Treaties have established reservations to manage land "in trust," have defined the boundaries of hunting and fishing rights, and have provided some social services.

In Virginia, treaties were signed by the colonial government before creation of the United States. Modern state-based tribal relations involved dealing with state rather than Federal agencies until 2015. The US Department of the Interior finally granted Federal recognition to the Pamunkey tribe in 2015.

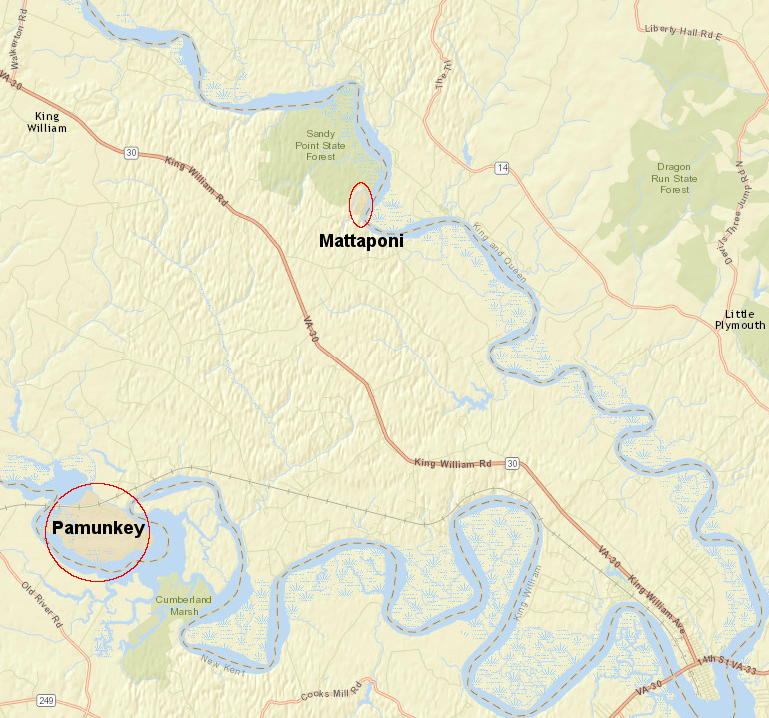

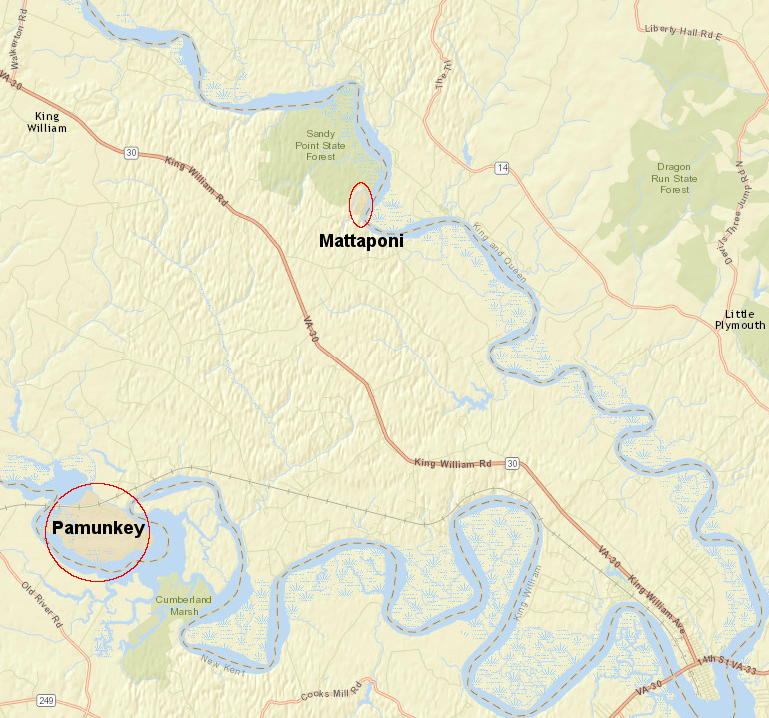

The 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation formalized a dedicated state reservation. Today's Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations date back to that treaty, and some preceding agreements. The US Congress had no role in creating those two Virginia reservations; another century would go by before the US Congress itself was created.

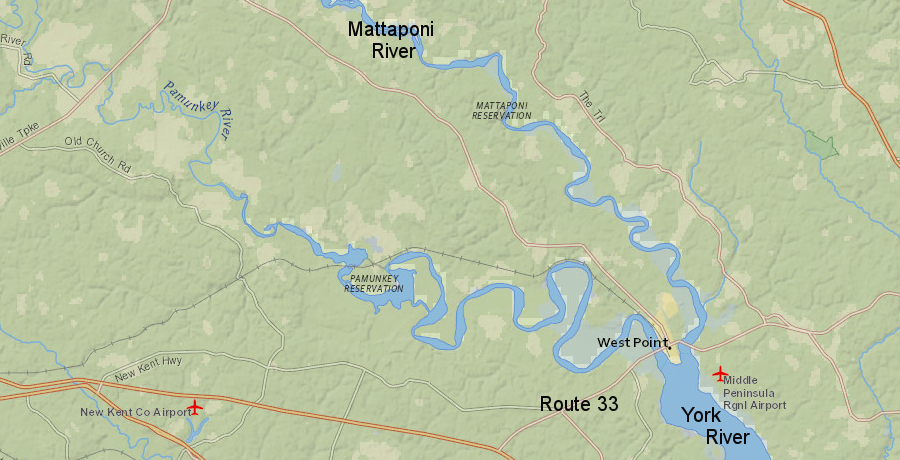

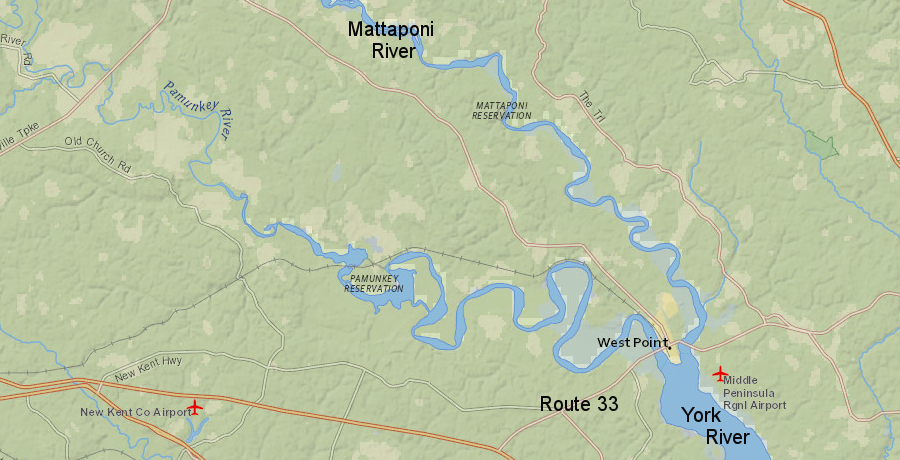

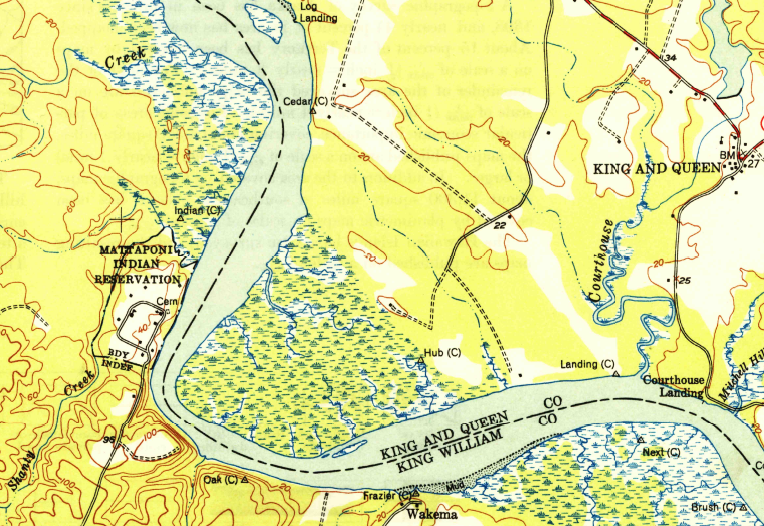

the Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations are in King William County, upstream of the headwaters of the York River at West Point

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia tribes began a concerted effort for state recognition after a 1900 law required separate railroad coaches for white vs. colored passengers, local officials during World War One sought to draft tribal members as blacks, and anthropologists James Mooney and Frank Speck initiated professional anthropological studies that spurred tribal organization.6

The General Assembly, through legislative action, granted official recognition in 1983 to the Chickahominy, Chickahominy Indians Eastern Division, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi. The legislature also re-affirmed in that bill the recognition of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi, the two tribes with official reservations in Virginia. Virginia governments had been engaged in official dealings with those tribes since the 1600's, and the 1983 legislation formalized their status as state-recognized tribes.

The General Assembly recognized the Nansemond in 1984 and the Monacan in 1989.

Members of recognized tribes can use their tribal identification cards when they go to the polls to vote, as well as the other forms of identification that all voters can use.7

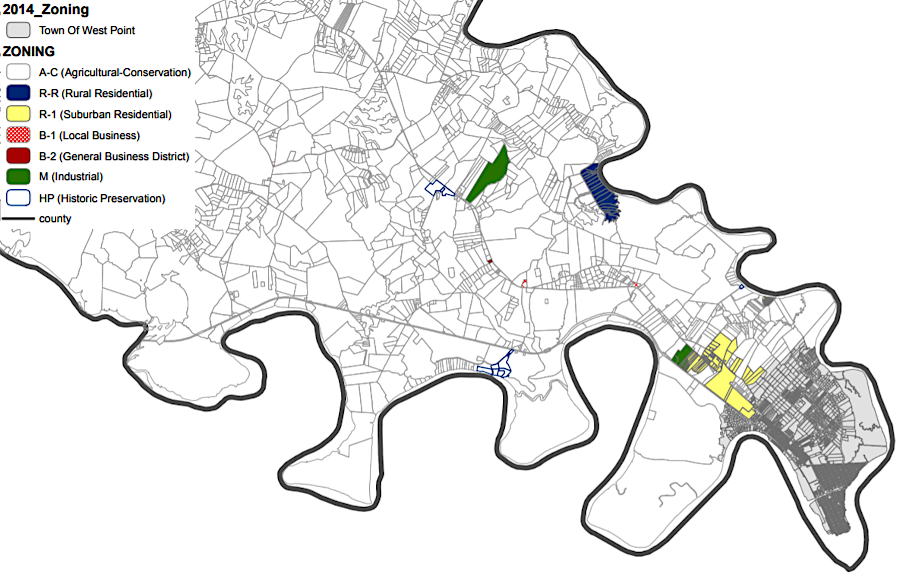

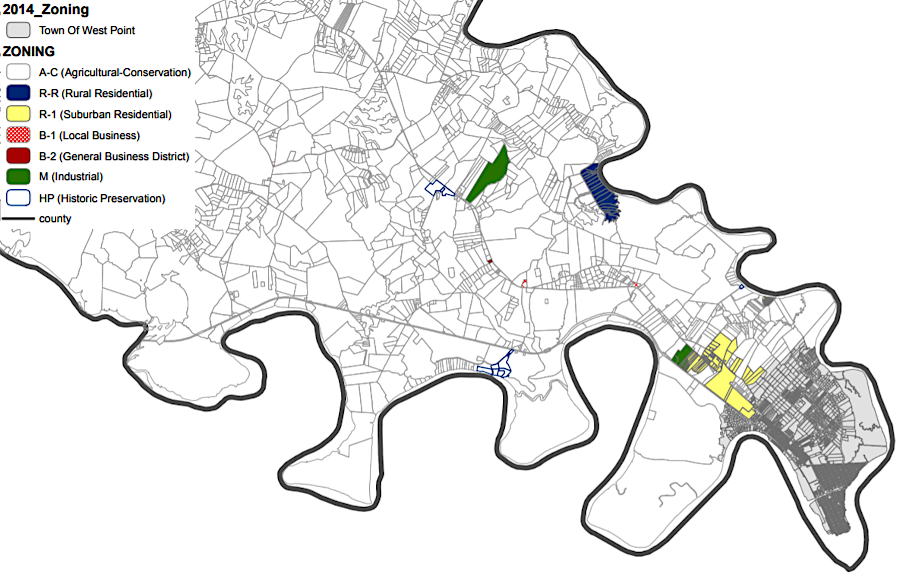

King William County does not designate zoning categories for the Town of West Point, but does claim the right to zone the Pamunkey Indian Reservation

Source: King William County, Zoning District Map

Virginia provides special fishing and fishing rights to members of recognized tribes. A person who "habitually" resides on a reservation or a member of one of the state-recognized tribes who resides in the Commonwealth does not have to obtain a state hunting or freshwater fishing license from the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

The fishing license exemption is limited to freshwater streams managed by the Department of Wildlife Resources. Saltwater fishing licenses are issued by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for fishing in the state's three mile zone in the Atlantic Ocean, the Chesapeake Bay, and the downstream portion of tidal rivers.

The Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations are on freshwater sections of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers, upstream of the Route 33 bridges at West Point that the two state agencies use to define saltwater vs. freshwater. Native American residents on the two state-recognized reservations do not need licenses to fish in the rivers where they live, and the Conservation Police Officers of the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources must be trained on fishing rights of reservation residents in the Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers.8

the state agencies that issue fishing licenses define the Route 33 bridges as the boundary for freshwater and saltwater licenses

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The General Assembly sought to create an administrative process to determine if additional tribes should receive state recognition. The Virginia Council on Indians, which was responsible for the administrative process and recommending approval or rejection by the General Assembly, defined six criteria in 2006:9

- 1. Show that the group's members have retained a specifically Indian identity through time

- 2. Demonstrate descent from an historical Indian group(s) that lived within Virginia's current boundaries at the time of that group's first contact with Europeans

- 3. Trace the group's continued existence within Virginia from first contact to the present

- 4. Provide a complete genealogy of current group members, traced as far back as possible

- 5. Show that the group has been socially distinct from other cultural groups, at least for the twentieth century and farther back if possible, by organizing separate churches, schools, political organizations or the like

- 6. Provide evidence of contemporary formal organization, with full membership restricted to people genealogically descended from the historic tribe(s)

However, no tribe met the criteria to the satisfaction of the members on the Virginia Council on Indians. To obtain state recognition, three tribes bypassed the administrative process in Virginia's executive branch and went directly to the General Assembly.

In 2010, the General Assembly granted recognition directly to the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Nottoway of Virginia, and Patawomeck tribes, using the legislative process to bypass the Virginia Council on Indians and its six criteria for recognition. The Virginia Council on Indians had recommended against recognition of the Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia, and the other two tribes never submitted petitions to the council.10

Legislators from the state legislative districts of those three tribes advocated for recognition in 2010, despite concerns that abandoning the administrative process could encourage other groups with less cohesion through time to seek recognition as an official tribe. News media highlighted the legislative hearing when entertainer Wayne Newton testified in support of Patawomeck recognition.11

After the 2010 General Assembly recognized the three tribes, the Virginia Council on Indians stopped meeting. In 2012, the General Assembly abolished the council, as part of the governor's reorganization of the executive branch of state government.

When the Virginia Council on Indians was abolished, it had received "letters of intent" but no formal petitions for recognition from the Appalachian Intertribal Heritage Association, Inc.; United Cherokee Indian Tribe of Virginia, Inc.; Blue Ridge Cherokee, Inc.; Tauxenent Indian Nation of Virginia; and Bear Saponi Tribe of Clinch Mountain Southwest Virginia.12

dancers at 2012 powwow in Fairfax County's Riverbend Park highlight that Native Americans have always been part of the population in Virginia

After the Virginia Council on Indians was dissolved, Virginia had only a legislative process for recognizing new tribes. For a brief period of time, the only path for groups to obtain recognition by the Commonwealth of Virginia as a tribe was passage of a law by the Virginia General Assembly.

Virginia's elimination of the administrative process and reliance upon just a legislative process for recognition was comparable to Tennessee's recent experience.

The Tennessee Indian Affairs Commission proposed to recognize six tribes in 2010. The decision was voided after the federally-recognized Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma sued. The state legislature then eliminated the Tennessee Indian Affairs Commission, abolishing that state's administrative process for tribal recognition.

The debate in Tennessee involves whether current groups were remnants of organized tribes with clear ties to the past, or just recently-formed "culture clubs" seeking legitimacy and access to Federal programs. In the 1600's and 1700's, the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Shawnee, and Yuchi nations lived in that area, but there are no state-recognized tribes in Tennessee today.13

In 2016, the General Assembly authorized the Secretary of the Commonwealth to create a new Virginia Indian Advisory Board to facilitate the state recognition process. The seven-member board includes leaders of already-recognized tribes, plus representatives from the Library of Virginia, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Virginia Department of Education, and a state university. The board's six criteria for state recognition are the same as those adopted by the Virginia Council on Indians in 2006, and are consistent with the criteria for Federal recognition.14

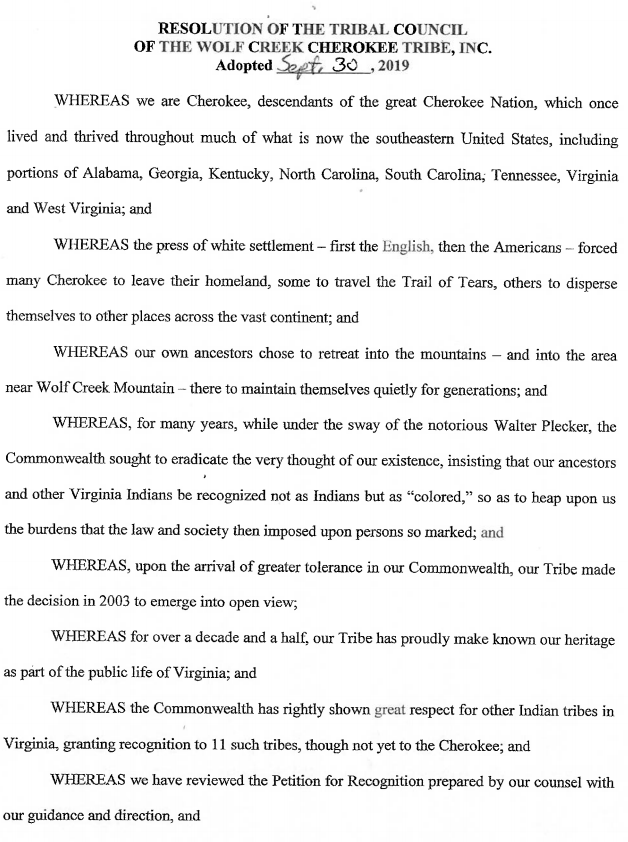

The Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe hired the law firm of Troutman Sanders to help navigate that group through the recognition process. The Tribal Council, meeting at the Wolf Creek Tribal Center and Museum in Henrico County, vote 6-0 on September 30, 2019 to submit its petition for state recognition to the Secretary of the Commonwealth, for action by the Virginia Indian Advisory Board.

In 2025, Confederated Tribes of the Wicocomico Indian Nation filed a letter stating their intent to pursue formal recognition by the Commonwealth of Virginia. To date, no action has been taken on either filing.

In 2013, the Appalachian Cherokee Nation and a separate group, the United Cherokee Indian Tribe of Virginia (Buffalo Ridge Band of Cherokee), managed to get legislation introduced in the General Assembly to grant them state recognition. The bills were not passed. Neither group has submitted any request for recognition to the Virginia Indian Advisory Board, since it was created in 2016.15

the Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe initiated the state recognition process in 2019

Source: Virginia Indian Advisory Board, Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe, Inc. Letter of Intent

In 2021, the seven Federally-recognized tribes organized a Sovereignty Conference at Lewis Ginter Botanical Gardens, on the northern edge of Richmond, at which Governor Northam spoke. The day was filled with information sharing regarding how recognized tribes and state/Federal agencies have interacted with each other in the past, and how they might work with each other in the future. The conference started an initiative to draft a "sovereign accord" that would interpret Virginia laws as they pertain to tribal sovereignty.

The chief of the Upper Mattaponi Tribe commented:16

- We feel like we're educating the state as we educate ourselves on the policy and procedures of the federal government and of just being federally recognized... Most of the time we're explaining things to the state when we're really calling to ask them for advice, but that's the way it has been.

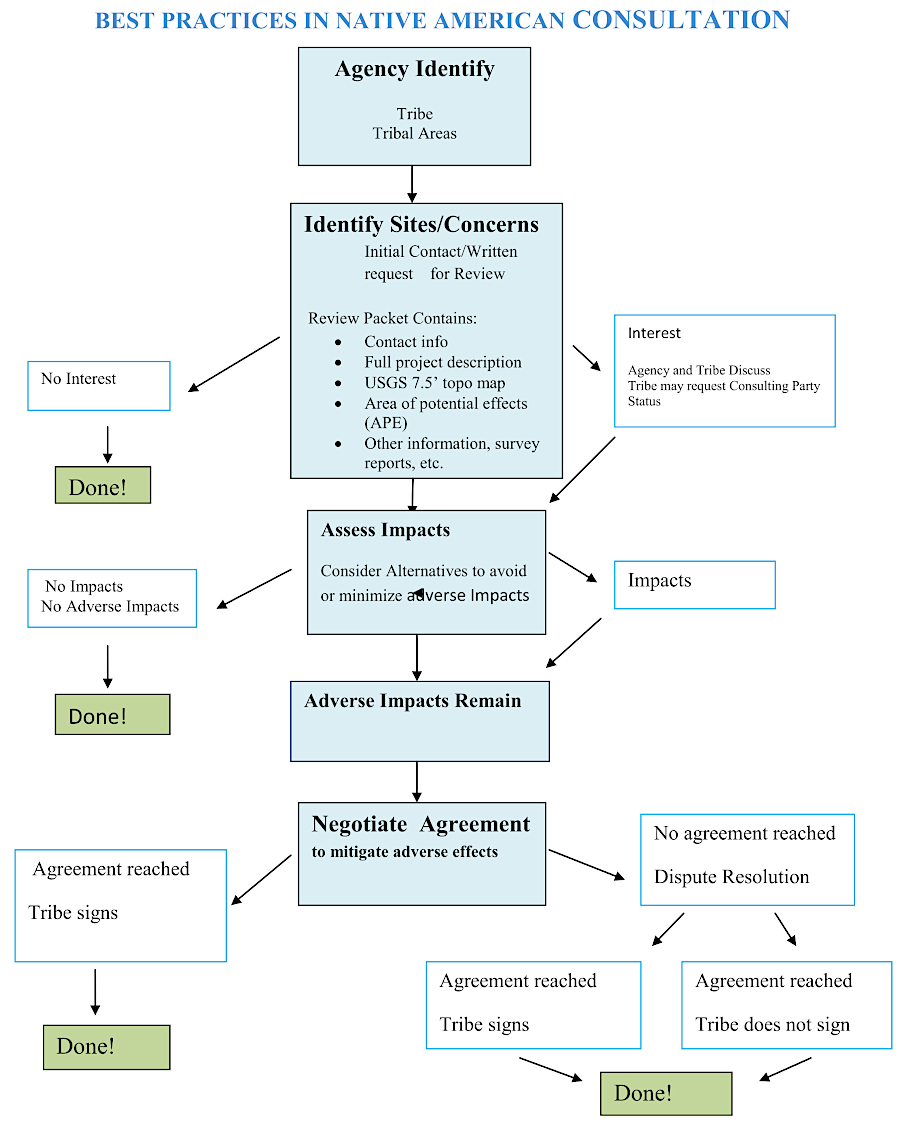

Governor Northam responded with an Executive Order that required the Department of Environmental Quality, Department of Conservation and Recreation, Department of Historic Resources and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to engage in government-to-government consultation with the Federally-recognized tribes before taking actions which affected them. An ombudsman position was established with responsibility to determine what proposals for state approval, such as nearby roads and pipelines, would trigger tribal consultation.

Since local governments often involved state officials in various development reviews, the Executive Order could prevent a repeat of Richmond County's approval of a new golf course and resort at Fones Cliffs. The chief of the Rappahannocks expressed her approval of the 2021 Executive Order:17

- Richmond County completely ignored us - didn't think we needed to know. We weren't even on their radar screen. We weren't at the table... What the governor [did] will bring us to the table for the first time, since prior to 1607, before anything gets done. And we get to discuss what's important to us.

Governor Northam's term ended on January 15, 2022. Subsequent governors had the option of retaining, revising, or revoking his Executive Order.

The General Assembly considered legislation in 2022 that would have permanently established the consultation requirement for projects affecting ancestral lands, and would have required tribal consent if human remains had to be reburied. The bill, SB 482, passed the State Senate on a unanimous 40-0 vote, but was killed in a House of Delegates subcommittee on a 5-5 tie.

In 2024, the legislature passed a law requiring state agencies to consult with federally recognized Native American tribes, if the agency was considering permits for a project that might affect a tribe's cultural or historic resources. That legislation was intended to prevent a repeat of the problem faced by the Monacan tribe almost a decade earlier.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality issued a permit in 2015 to the James River Water Authority, and construction of its planned pump station and water pipeline would damage the historic Monacan capital of Rassawek. The state agency never consulted the tribe, and the water authority did not notify the tribe of the planned project until 2017. After a five year battle, the James River Water Authority finally chose to build at a different location.18

The General Assembly passed new legislation in early 2022 authorizing tribes to receive grants directly from the Virginia Land Conservation Fund. That eliminated the need for tribes to partner with a non-profit or a government agency. Later in that year, grants were awarded to the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe to purchase 800 acres of forested land along the Mattaponi River, and to the Rappahannock Tribe of Virginia to purchase 700 acres at Fones Cliffs.19

In 2024, the General Assembly passed legislation that designated an ombudsman for tribal consultation, treating them as separate sovereign nations. HB 1157 required state agencies and local governments to consult Federally-recognized tribes on environmental, cultural, and historical permits, reviews, and projects that might impact them.

The bill was intended to prevent what happened when the James River Water Authority advanced plans to build a pumping station on the James River at Point of Fork and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) approved a state permit in 2015, catching the Monacan Nation by surprise.20

HB2134 passed the legislature in 2025, but Governor Youngkin vetoed the bill. The legislation updated the Code of Virgina to reflect Federal recognition of several tribes, and replaced "Tribal Nations in the Commonwealth" with "tribes." HB2134 also included the sentence:21

- The Commonwealth endeavors to maintain positive government-to-government relationships with the federally recognized tribes within the present-day external boundaries of the Commonwealth.

The governor sought to amend the bill, but his proposed change was not adopted by the General Assembly. His veto message said:22

- Pursuant to Article V, Section 6 of the Constitution of Virginia, I veto House Bill 2134, which establishes definitions related to tribal recognition and makes technical updates throughout the Code of Virginia to reflect the federal recognition of Virginia tribes.

-

- While the intent to ensure consistency in terminology across the Code is appropriate, the bill includes language referring to a “government-to-government” relationship between the Commonwealth and federally recognized tribes. This phrase introduces a legal framework that does not align with Virginia's current statutory or constitutional structure and may have unintended implications for the Commonwealth's legal and financial responsibilities.

-

- To address this concern and allow the many other updates in this bill to be enacted this year, I proposed a targeted amendment to remove the “government-to-government” designation, which the General Assembly declined to adopt. Without this change, the legislation poses serious risks to ongoing litigation.

-

- Accordingly, I veto this bill.

At the time of the veto, the issue of a government-to-government relationship was already part of a lawsuit. The Virginia Attorney General claimed the Nansemond tribe was engaged in fraudulent billing practices for tribal health-care services and reimbursement of Medicaid expenses at Fishing Point Healthcare, especially for home health care. As a tribal entity, the Nansemond received a far higher rate for Medicaid reimbursements compared to private companies. The Upper Mattaponi were also providing health care services, but at a much lower scale.

The state stopped paying the Medicaid claims submitted by the Nansemond, triggering what the Washington Post called:23

- ...the first instance of Virginia facing a government-to-government clash with one of its newly recognized Native tribes.

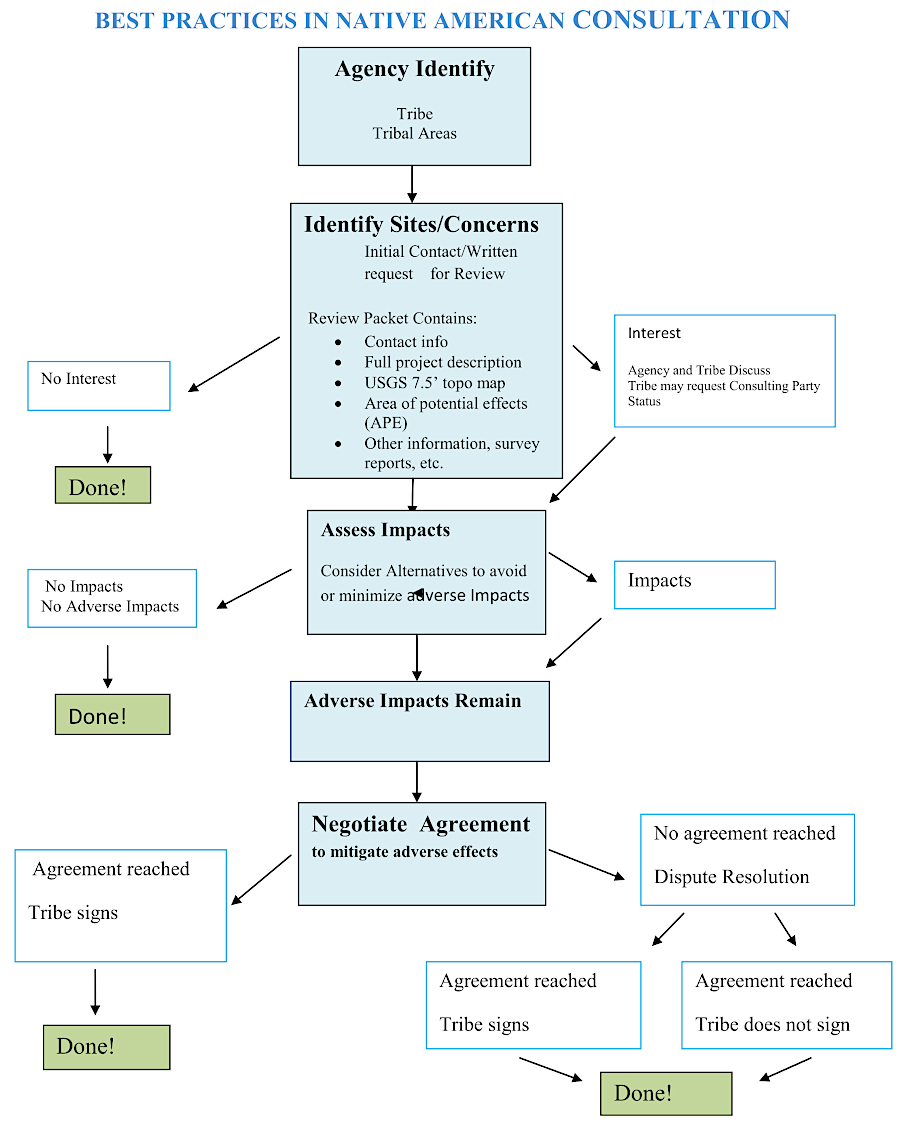

tribal consultation and coordination process in Virginia

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Best Practices in Native American Consultation

Links

Mattaponi Reservation on Mattaponi River

Source: US Geological Survey 1:24,000 scale topographic map, 1949 - King And Queen

References

1. "Meet the Native American tribe that wants to be the first Cherokee group recognized by Virginia," The Virginia Mercury, November 28, 2019, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2019/11/28/meet-the-native-american-tribe-that-wants-to-be-the-first-cherokee-group-recognized-by-virginia/ (last checked November 29, 2019)

2. "About Us," Wolf Creek Cherokee, http://www.wolfcreekcherokee.com/about-us.html (last checked November 28, 2019)

3. "All Actions H.R.984 — 115th Congress (2017-2018)," Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/984/all-actions?overview=closed#tabs; "H.R. 5073 (106th): Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2000," GovTrak, July 27, 2000, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/106/hr5073/text/ih (last checked November 28, 2019)

4. "H.R.5553 - Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia Federal Recognition Act," 118th Congress, https://www.wtvr.com/news/national-news/patawomeck-tribe-virginia-tribe-still-fighting-for-recognition-jan-21-2024 (last checked January 21, 2024)

5. Charles D. Bernholz, Brian T. O'Grady, "Insights from editions of The Annual Register regarding later variants of the Royal Proclamation of 1763: An application of Levenshtein's edit distance metric," University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, http://annualregister1763.unl.edu/ (last checked May 27, 2012)

6. Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, pp.212-218

7. "Virginia's What If's," Virginia Department of Elections, September 2019, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/media/formswarehouse/election-management/election-day-instructions-and-forms/What_Ifs_2019.pptx (last checked November 30, 2019)

8. "Fishing License Information & Fees," Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, https://dwr.virginia.gov/fishing/regulations/licenses/; "Recreational Saltwater Fishing License Boundaries," Virginia Marine Resources Commission, http://mrc.virginia.gov/mrc_license_boundaries.shtm (last checked October 6, 2021)

9. "Tribal Recognition Criteria," Virginia Council on Indians, May 16, 2006, http://indians.vipnet.org/resources/tribalRecognitionCriteria.pdf (backup copy) (last checked June 3, 2012)

10. "Annual Executive Summary on the Interim Activity and Work of the Virginia Council on Indians," Virginia Council on Indians, 2011, http://leg2.state.va.us/dls/h&sdocs.nsf/0/59f493fd3ea78725852576ce005f87aa?OpenDocument; "Recognition Committee Report to the VCI - Nottoway Tribe of Virginia Petition for State Recognition," Virginia Council on Indians, April 17, 2009, archived copy (last checked October 31, 2015)

11. "Wayne Newton advocates for Virginia state recognition of Patawomeck Indian tribe," Washington Post, February 3, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/02/02/AR2010020203562.html (last checked June 3, 2012)

12. "State vs. federal recognition for Indian tribes," The Virginian-Pilot, June 10, 2009, http://hamptonroads.com/2009/06/state-vs-federal-recognition (last checked March 5, 2014); "State Recognition of Indian Tribes," Virginia Council on Indians, http://indians.vipnet.org/stateRecognition.cfm (no longer online - last checked June 3, 2012)

13. "House bill recognizing six groups as Indian tribes shuttled off for summer study," Chattanooga Times Free Press, April 10, 2012, http://timesfreepress.com/news/2012/apr/10/house-bill-recognizing-six-groups-indian-tribes-sh/?breakingnews; "State Recognition of Six Indian Tribes 'Void and of No Effect'," Nashville News-Sentinel, September 4, 2010, http://blogs.knoxnews.com/humphrey/2010/09/state-recognition-of-six-india.html; "New Effort to Recognize Tennessee Indian Tribes Underway," Nashville News-Sentinel, March 9, 2012, http://blogs.knoxnews.com/humphrey/2012/03/a-renewed-effort-to-grant.html (last checked October 6, 2013)

14. "Virginia Indian Advisory Board," Secretary of the Commonwealth, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/virginia-indians/virginia-indian-advisory-board/; "Tribal Recognition Criteria," Virginia Indian Advisory Board, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/virginia-indians/virginia-indian-advisory-board/tribal-recognition-criteria/ (last checked November 29, 2019)

15. "Resolution of the Tribal Council of the Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe," September 30, 2019, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/secretary-of-the-commonwealth/indian-advisory-board/pdf/Wolf-Creek-Cherokee-Tribe---Letter-of-Intent.pdf; Letter to the Virginia Indian Advisory Board from the Confederated Tribes of the Wicocomico Indian Nation Inc., February 14, 2025, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/secretary-of-the-commonwealth/indian-advisory-board/Confederated-Tribes-of-the-Wicocomico-Indian-Nation.pdf; "Virginia Indian Advisory Board on State Recognition," Secretary of the Commonwealth, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/virginia-indians/virginia-indian-advisory-board/ (last checked October 26, 2025)

16. "Virginia's federally recognized tribes begin drafting a sovereignty accord," Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 6, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/virginia-s-federally-recognized-tribes-begin-drafting-a-sovereignty-accord/article_0660733b-68c8-5f8b-aecc-594e26abe921.html (last checked October 6, 2021)

17. "Virginia first in U.S. to give Indigenous tribes a say in state permitting process," Free Lance-Star, November 20, 2021, https://fredericksburg.com/news/local/virginia-first-in-u-s-to-give-indigenous-tribes-a-say-in-state-permitting-process/article_72579cc2-baad-5b56-a0e6-35b319785219.html (last checked November 22, 2021)

18. "Virginia Republicans kill bill giving Indian tribes a role in reviewing development on ancestral lands," Washington Post, March 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/03/02/virginia-general-assembly-indian-tribes/; "SB 482 Tribal Nations; consultation w/ federally recognized, permits and review w/ potential impacts," Virginia General Assembly, 2022 Session, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?221+sum+SB482; "Will Virginia tribes finally get their say?," Virginia Mercury, April 2, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/04/02/will-virginia-tribes-finally-get-their-say/ (last checked April 2, 2024)

19. "Tribes awarded state grants for the first time to conserve Va. forestland," Virginia Mercury, November 22, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/11/22/tribes-awarded-state-grants-for-the-first-time-to-conserve-va-forestland/ (last checked November 28, 2022)

20. "For a young Native advocate, public lands hold the key," Bay Journal, September 30, 2024, https://www.bayjournal.com/news/people/for-a-young-native-advocate-public-lands-hold-the-key/article_6addb0f4-7d03-11ef-95f2-732339696c6c.html; "Virginia lawmakers pass bill requiring permit input from Indigenous tribes," Bay Journal, March 8, 2024, https://www.bayjournal.com/news/people/virginia-lawmakers-pass-bill-requiring-permit-input-from-indigenous-tribes/article_dbc0855a-dd6a-11ee-a665-073da2a11c0a.html; "Title 2.2. Administration of Government - Subtitle I. Organization of State Government - Part A. Office of the Governor - Chapter 4. Secretary of the Commonwealth - Article 1. General Provisions - § 2.2-401.01. Liaison to Virginia Indian tribes; Ombudsman for Tribal Consultation; Virginia Indigenous People's Trust Fund," Code of Virginia, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/2.2-401.01/; "Will Virginia tribes finally get their say?," Virginia Mercury, April 2, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/04/02/will-virginia-tribes-finally-get-their-say/ (last checked October 2, 2024)

21. "HB2134 American Indians, Va. recognized tribes, and federally recognized tribes; definitions, sovereignty - Enrolled," General Assembly, 2025 session, https://lis.virginia.gov/bill-details/20251/HB2134 (last checked May 5, 2025)

22. "HB2134 - Governor's Veto Explanation," General Assembly, 2025 session, https://lis.virginia.gov/bill-details/20251/HB2134/text/HB2134VG (last checked May 5, 2025)

23. "Virginia tribe and state officials accuse each other of Medicaid fraud," Washington Post, May 7, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2025/05/07/virginia-nansemond-tribe-lawsuit-fraud/ (last checked May 8, 2025)

the 2016 advertisement for the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe highlighted the historical status of the tribe

Source: Facebook, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe (September 23, 2016)

"Indians" of Virginia - The Real First Families of Virginia

Virginia Places