"Indians not taxed" were excluded from birthright citizenship in the 14th Amendment

Source: National Archives, America's Founding Documents

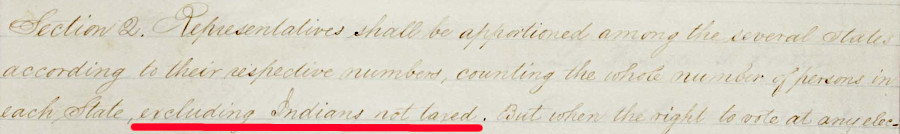

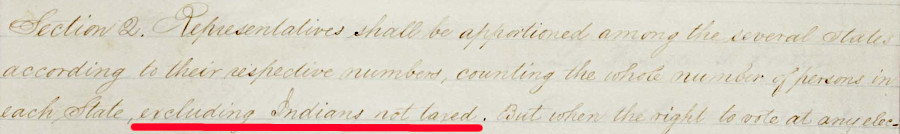

In the US Constitution that was ratified in 1788, "Indians not taxed" were not counted as citizens when determining a state's population for the number of seats in the US House of Representatives. In contrast, 3/5ths of the number of enslaved people were calculated for state representation.

The US Supreme Court ruled in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision that Native Americans were qualified to become citizens. In that famous legal case, the court drew a key distinction between two non-white segments of American society in the 1850's. The justices ruled that nearly every black person, enslaved or not in 1857, was ineligible to become a citizen:1

Native Americans were treated differently, though they were viewed through the same lens of white supremacy (emphasis added):2

Because Native Americans were not citizens with the right to vote, they were excluded from the decennial census used to reapportion the numbers of members per state in the US House of Representatives, but were recorded in special Indian Schedules for the 1900 and 1910 censuses. They were also not eligible to be drafted by Virginia officials, even during the Civil War. Members of the Pamunkey tribe allied with the Union, and volunteered or were hired to serve as guides, boatmen, and spies.

The 14th Amendment in 1868 established birthright citizenship and clarified that blacks who had been born in the United States were automatically citizens. By both custom and court interpretations of various laws, Native Americans still were excluded from the political process and not counted in the census every 10 years because the 14th Amendment did not grant citizenship automatically to Native Americans.

Section 2 of the 14th Amendment still excluded "Indians not taxed" from being counted towards state representation in the US House of Representatives:3

Virginia was Military District #1 during Reconstruction after the Civil War, administered by US military officials who appointed the governor. The military decided that the Pamunkey living in King William County, as well as those living on their reservation (together with the Mattaponi at the time),

In 1870 the Senate Judiciary Committee said:4

"Indians not taxed" were excluded from birthright citizenship in the 14th Amendment

Source: National Archives, America's Founding Documents

When the Pamunkey asked for the state to provide a schoolteacher without subjecting the tribe to state taxes, the state government clarified the citizenship status of Native Americans under the 1870 state constitution:5

The 1887 Dawes Act created a path to citizenship. The law encouraged breaking up reservations, where land was communally held in trust by the US Government, into allotments where individuals had all property rights. Native Americans who accepted an allotment, which brought with it the responsibility to pay taxes and in theory the right to vote, became citizens.

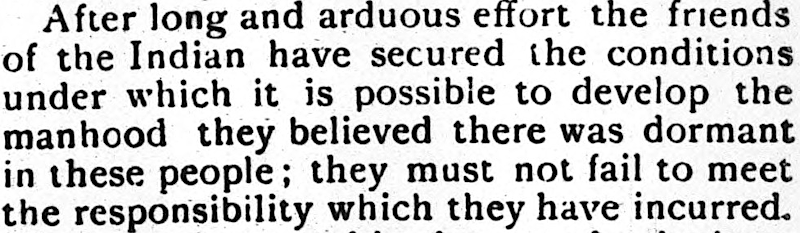

Federal policy at the time was to assimilate Native Americans into the cultural patterns of the whites who controlled economic and political power. Those who abandoned traditional ways of living would be allowed to participate in the democratic process. In Virginia, Hampton Institute received Federal funding to operate a boarding school for Native Americans. the school supported the "melting pot" approach, though all graduates - black and Native American - would live in a society segregated by race.

Hampton Institute organized annual "Indian Day" pageants on February 8, when the anniversary of passage of the Dawes Act was described as "Indian Emancipation Day." Senator Dawes viewed the school's effort to train Native American students to act like whites as a prerequisite to citizenship:6

Hampton Institute's Indian boarding school was designed to assimilate Native Americans and replace their traditional culture, viewed as "savage" by white Americans

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Southern Workman (March 1, 1887, p.31)

There have never been Federal reservations for Native Americans within Virginia. All the land within the current boundaries of Virginia became part of the United States before the public domain was established, starting with Virginia's cession of the Northwest Territory to the Continental Congress in 1782. As a result, no acres in Virginia were ever "reserved" from disposal by the Federal government. Land ownership within reservations established by Virginia's colonial government were not affected by the 1887 Dawes Act.

Virginia treated Native Americans living on defined reservations as "wards of the state," comparable to young children and those who were mentally incompetent and unable to represent themselves in court. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations have survived in part because they were represented in legal matters by trustees that were relatively responsible, in contrast to the demise of reservations once held by other tribes.

Trustees were initially chosen by the local county court. In 1799 the Pamunkey gained the right to make their own selection of trustees who would represent the tribe:7

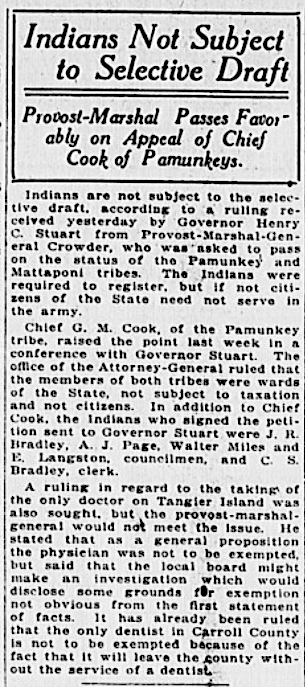

In 1917, after the United States entered World War I, the Pamunkey objected to plans by local draft boards to force tribal members into the US military. Because the Pamunkey were not citizens, they were not taxed and they could not vote - and based on the Civil War precedent, they could not be drafted. They chose to highlight their diminished status by objecting to being drafted to fight for a government in which they had no political voice or representation.

On August 25, 1917, Chief George Cook testified that:8

After winning exemption from the draft, several Pamunkey - including Chief Cook's son - then enlisted as volunteers.9

Native Americans born in the United States were finally classified as US citizens after the US Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act on June 2, 1924. At the time, 40% of Native Americans in the United States were still "Indians not taxed" and therefore not citizens. The language in the Indian Citizenship Act was succinct:10

With passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, Federal policy was to assimilate Native Americans into society and eliminate their unique status as "Indians not taxed." That created a conflict with the social agenda of Virginia's white leaders.

The same year the US Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, the Virginia General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act. Virginia's Jim Crow laws, passed after the Civil War, legalized segregation by race. A person's classification determined which schools they could attend, which bathrooms/water fountains they could use, and especially who they could marry and produce children. The laws were designed to segregate non-whites from having social interactions with whites, with everyone designated as either "White" or "Colored."

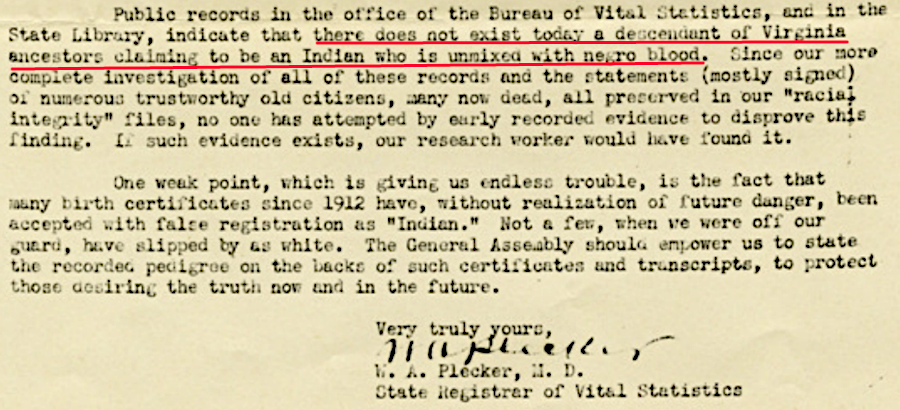

Walter Plecker, the State Registrar of Vital Statistics, led the implementation of the Racial Integrity Act. He tried to force local officials to classify everyone as either White or Colored, eliminating the designation as Indian whenever possible. By his interpretation of family histories and assessment of physical characteristics, all Native Americans in Virginia had at least "one drop" of African blood.

Plecker contended that members of the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and the other tribes without state-designated reservations should be classified as Colored because miscegenation had corrupted their Native American gene pool. He sought to anyone with any percentage of African ancestry from "passing" as white, marrying into white society, and having children that would ultimately dilute the supposed purity of the white race.

using the 1924 Racial Integrity Act, the State Registrar of Vital Statistics sought to force Native Americans into second-class citizenship

Source: Library of Virginia, Walter Plecker Asserted that Virginia Indians No Longer Exist, December 1943

Whether designated as Indian or Colored, Native Americans in Virginia were citizens after 1924 - but their rights as citizens were limited by their racial classification. To vote they had to overcome laws designed to restrict the Virginia electorate, including the poll tax and various constraints on registration. Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 by the US Congress did not immediately establish social or economic equality, but it did finally enable Native Americans in Virginia to vote.

The Federal government dropped its assimilation policy with passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and recognized a level of Native American sovereignty on reservations established by Federal treaties and laws. The Bureau of Indian Affairs lacked funding, but was willing to assist individuals in Virginia with at least one-fourth Native American blood.11

Acknowledging Native American individuals as citizens did not automatically lead to acknowledging tribes as a form of government. Formal recognition of tribes by Virginia's state government began in 1983. Federal recognition began in 2018.

the Pamunkey got confirmation in 1917 that they were exempt from the military draft

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Richmond Times-Dispatch (21 August 1917)