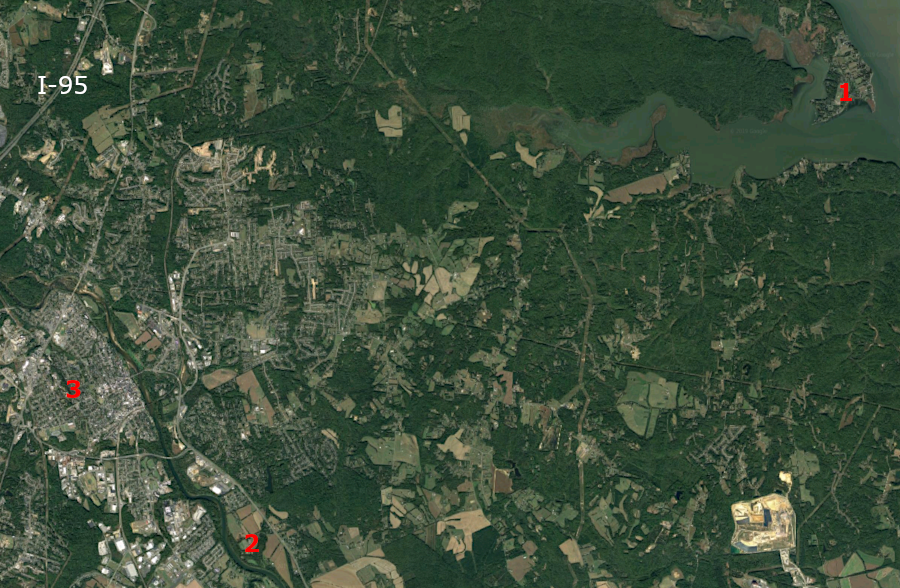

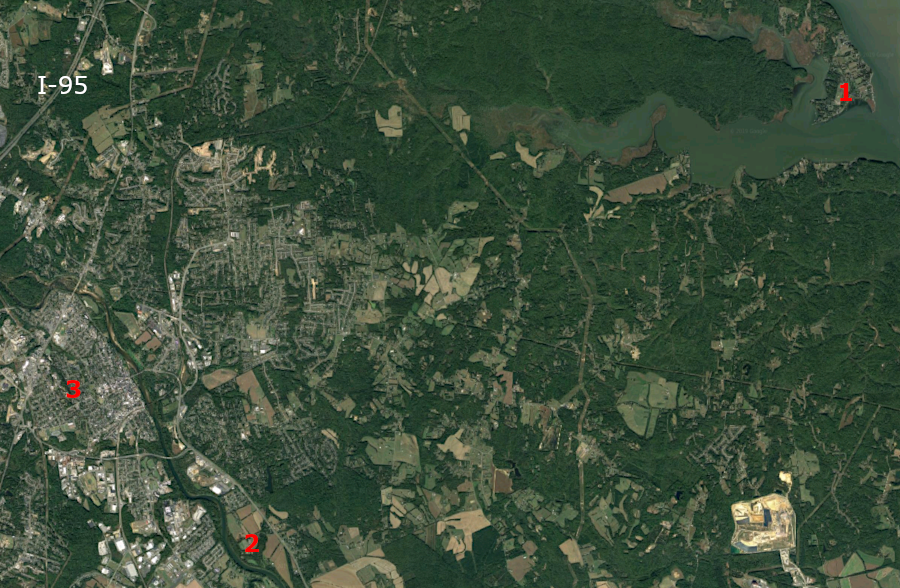

the Patawomeck once lived at Marlboro Point (1), and are developing a new tribal center at Duff Green Park (2) near Fredericksburg (3)

Source: GoogleMaps

the Patawomeck once lived at Marlboro Point (1), and are developing a new tribal center at Duff Green Park (2) near Fredericksburg (3)

Source: GoogleMaps

When John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608 and visited the mouth of Potomac Creek, he first met the Patawomeck/Patawomeke with their palisaded town.

The Patawomeck lived on the fringe of Powhatan's paramount confederacy. They quickly realized that they could deal directly with the English. The "tassantassas" could use their ships to avoid crossing through Tsenacommacah. Despite Powhatan's efforts to starve the English, the Patawomeck traded corn for iron tools, textiles, and prestige goods such as copper and beads.

In 1609, the Patawomeck provided a safe refuge for Henry Spelman when he ran away from Werowocomoco. Two years later, Lord de la Warre described the Patawomeck chief "as great as Powhatan," rather than subordinate to him.

In 1613, they betrayed Powhatan's emissary rather than provide the required tribute to the paramount chief. Japasaws, the Patawomeck chief, sold Pocahontas to the English ship captain Samuel Argall. Japasaws receive at least one copper kettle in exchange for his treachery.

Powhatan lost control over the periphery of Tsenacommacah. When Opechancanough organized assaults on the English in 1622 and 1644, he was unable to get the Patawomeck to join. 1

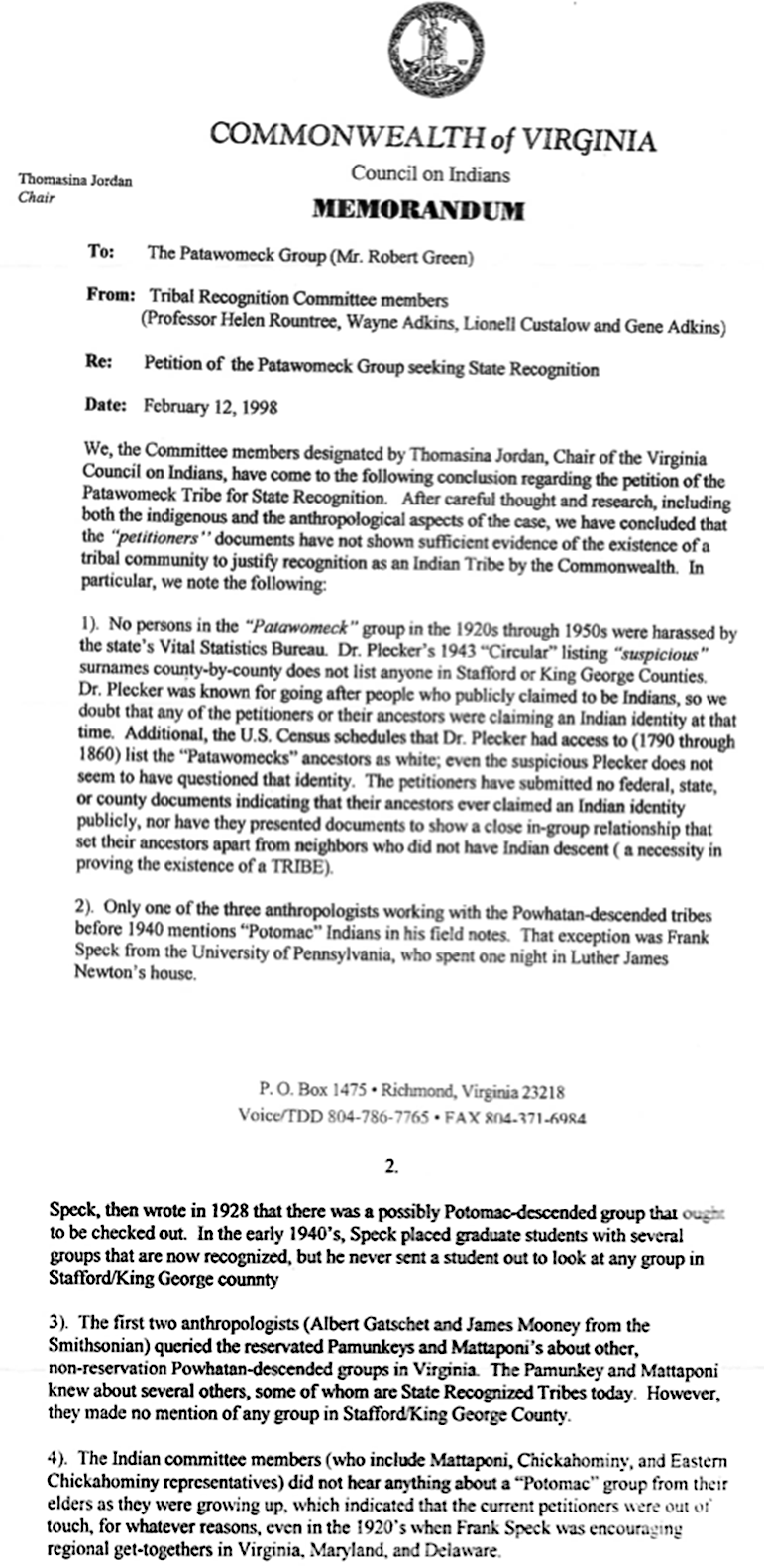

In 1998, the Virginia Council on Indians declined to support state recognition of the Patawomeck Tribe. The rejection letter noted that Dr. Walter Plecker had not harassed anyone in Stafford or King George counties who claimed to be "Indian" but were listed as "White" in the state's vital records, and that other Native American groups were unfamiliar with a remnant tribe in the area.

The 2010 General Assembly bypassed the Virginia Council on Indians. The legislators conferred official state recognition on the Patawomeck tribe.2

The tribe sought to rebuild a tribal village at Duff Green Memorial Park, on Marlborough Point in Stafford County. That would provide a permanent base, eliminating the need to create a temporary site each year at Fort AP Hill for education and outreach. At the time, the tribe was the only one officially recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia without land for a permanent home.

The original town site is underwater now, but the park is near where the Patawomeck lived when Pocahontas visited in 1613. A Stafford County supervisor, supporting donation/lease of the local park to the tribe, noted in 2019 the tourism potential related to historical sites:3

In 2019, the county and tribe arranged for a 10-year lease of a 17 acres at Duff Green Park, with optional lease renewals for up to 50 years. The tribe used the Duff house to offer educational museum exhibits, and to build a cultural village showcasing native plants of significance to the lifeways in the past. The entire project, including upgrading the access road, was projected to cost only $334,000.4

In 2022, US Representative Rob Wittman expressed support for the tribe to get Federal recognition through Congressional action. Such recognition would spur the Smithsonian to repatriate artifacts acquired after an archeological dig at Marlborough Point from 1935-1940. The artifacts could be displayed at the tribe's Little Falls Farm cultural center.5

Three members of Congress, Reps. Abigail Spanberger, Jennifer Wexton, and Jen Kiggans, introduced the "Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia Federal Recognition Act" in 2023. It claimed that the tribe had coalesced around the White Oak church after 1790, but standard recognition process was inadequate because the tribe had been disrupted by colonial supprsion:6

The Stafford County Historical Society opposed Federal recognition of the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia (PITV):7

The response from two professors from the College of William & Mary was blunt. They said the local historical society claim was "defamatory, misinformed, and salacious," and:8

The Nature Conservancy transferred 870 acres of land along the Rappahannock River to the Patawomeck Indian Tribe in 2025. The land had been donated to the Nature Conservancy four decades earlier, and the Virginia Outdoors Foundation held a conservation easement on the acreage. The Trust for Public Land facilitated the transfer, using a North American Wetlands Act Grant.9

Stafford County officials remained less confident regarding the legitimacy of the tribe, despite state recognition in 2010. In 2025 the county declined to renew a lease issued 10 years earlier for the tribe to use 6.5 acres near Aquia Landing Park. County officials required further documentation of the tribe's heritage before renewing the lease. The county's Parks and Recreation Department was tasked with maintaining the site, which included a medicine wheel.

Some local historians contended that the Patawomeck Tribe was "a collection of White people incorrectly claiming indigenous heritage." They had highlighted in 2010 that the Census records for people claiming to be Patawomeck descendants had listed their ancestors as "White" for 200 years, long before Walter Plecker began his official efforts to eliminate legal references to "Indian" ancestry in 1924. In contrast, the historians noted that ancestors of the Rappahannock and Chickahominy chiefs had some historical documentation indicating that they were considered to be "Indian" rather than "white."10

the Virginia Council of Indians objected to state recognition of the Patawomeck in 1998, but the General Assembly officially recognized the tribe in 2010

Source: Fredericksburg Free Press, The Virginia Council on Indians and the Patawomecks