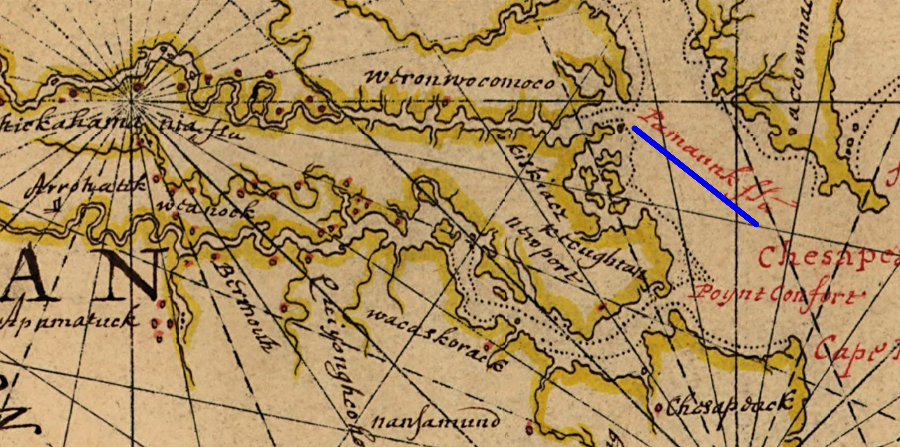

in the mid-1600's, the Dutch still used the name "Pamunkey" rather than "York" River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Atlantic Coast of North America from the Chesapeake Bay to Florida (Joan Vinckeboons, 1639?)

in the mid-1600's, the Dutch still used the name "Pamunkey" rather than "York" River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Atlantic Coast of North America from the Chesapeake Bay to Florida (Joan Vinckeboons, 1639?)

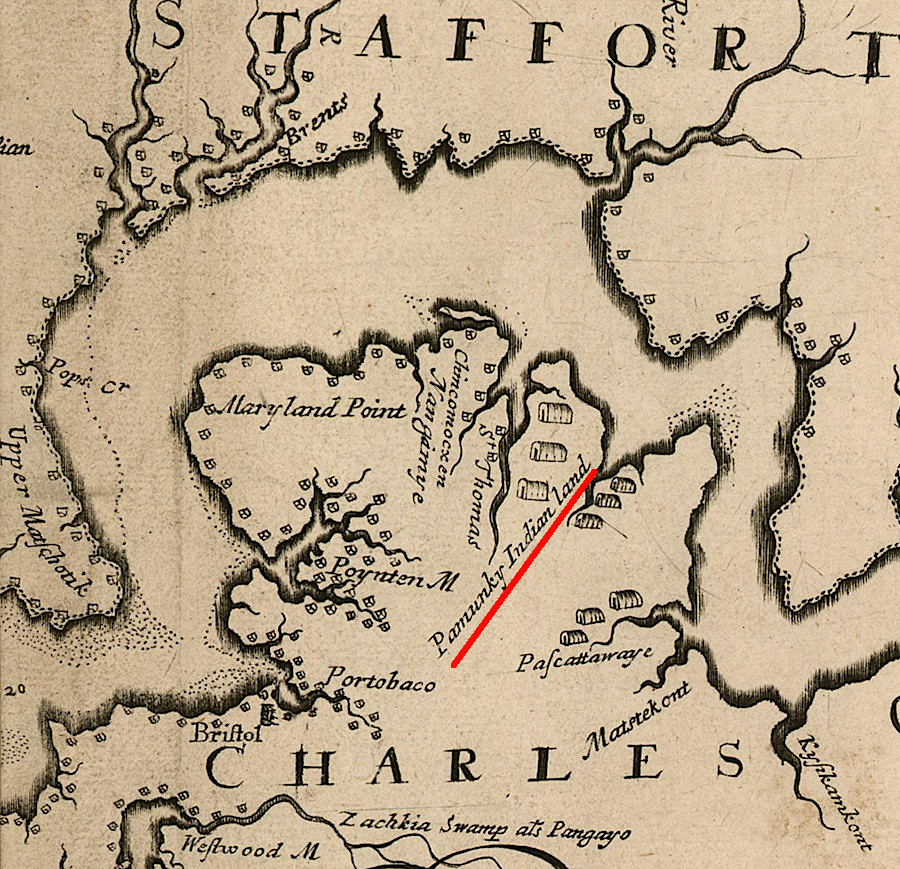

the Confederate Engineer Bureau documented how the Richmond and York River Railroad crossed the Pamunkey reservation

Source: Library of Congress, Map of King William County, Va (by Benjamin Lewis Blackford, c.1865)

When the English colonists arrived in 1607, they sailed up the river they named the James. Captain Newport met a weroance named Tanx (Little) Powhatan, who was in charge of a town just downstream of the Fall Line. The English thought they had contacted the paramount chief Powhatan.

The colonists later discovered that the paramount chief lived with the Pamunkey at Werowocomoco. The Powhatan tribe living at what is now Tree Hill in Henrico County was separate from the Pamunkey tribe living at Werowocomoco, located on Purtan Bay of the York River. The paramount chief, known as Powhatan or Wahunsenacawh, ruled over both tribes.1

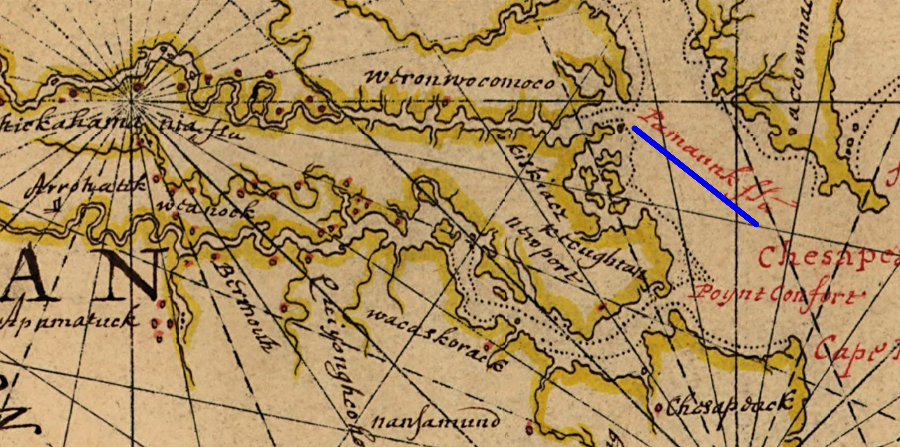

the Pamunkey lived on the York River, while the town of the Powhatan was on the James River

Source: Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean, Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

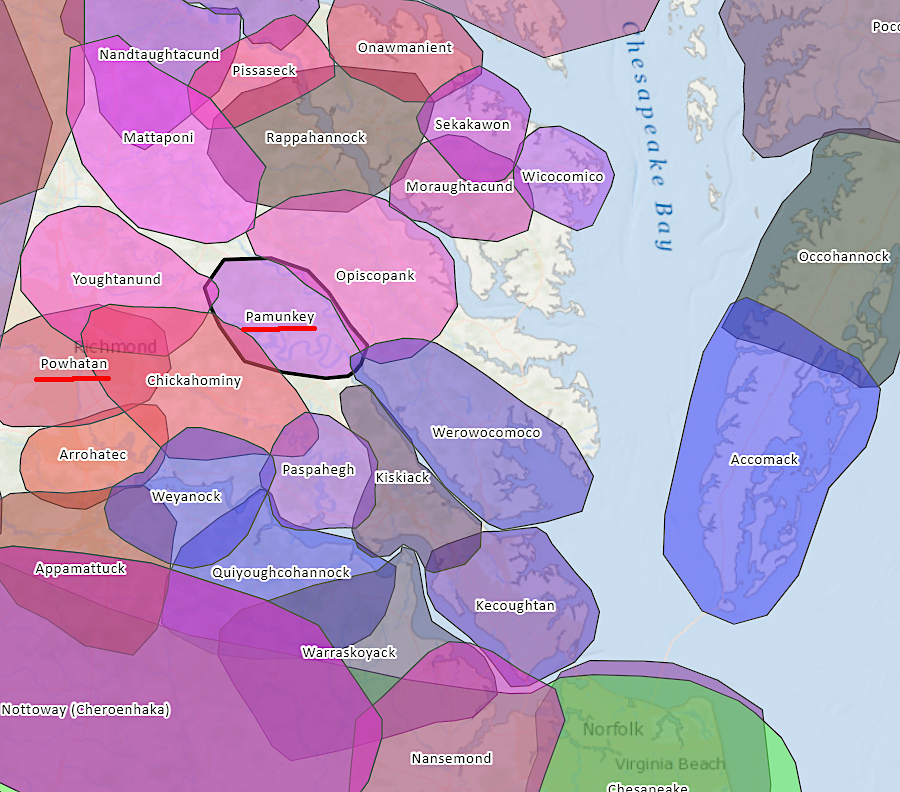

just before Bacon's Rebellion, some of the Pamunkey may have been living with the Piscataway in Maryland

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Virginia and Maryland As it is planted and Inhabited this present Year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1673)

just prior to the American Revolution, John Henry documented where the Pamunkeys had lived since the English first arrived

Source: Library of Congress, A new and accurate map of Virginia (by John Henry, 1770)

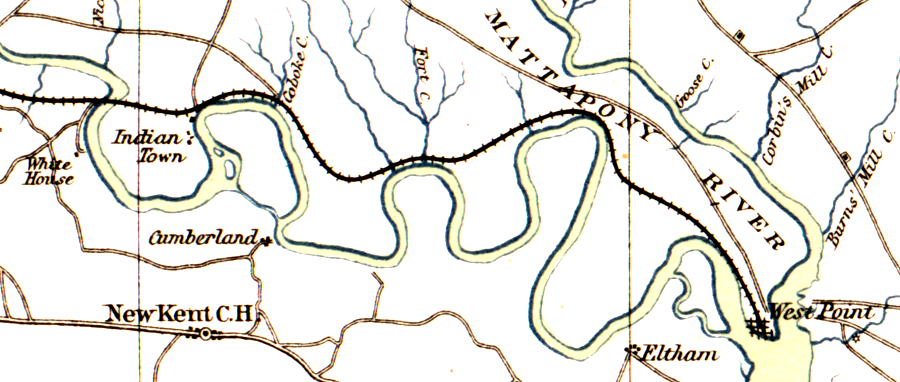

prior to the Civil War, the Richmond and York River Railroad built its line across the lands of the Pamunkey Tribe ("Indian Town") to connect Richmond to the deeper port at West Point

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe, Va.

During the Civil War, the Union Army occupied the territory around the Pamunkey after the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

Source: Library of Virginia, "Union Tooth and Nail": Pamunkey Indians and the Civil War

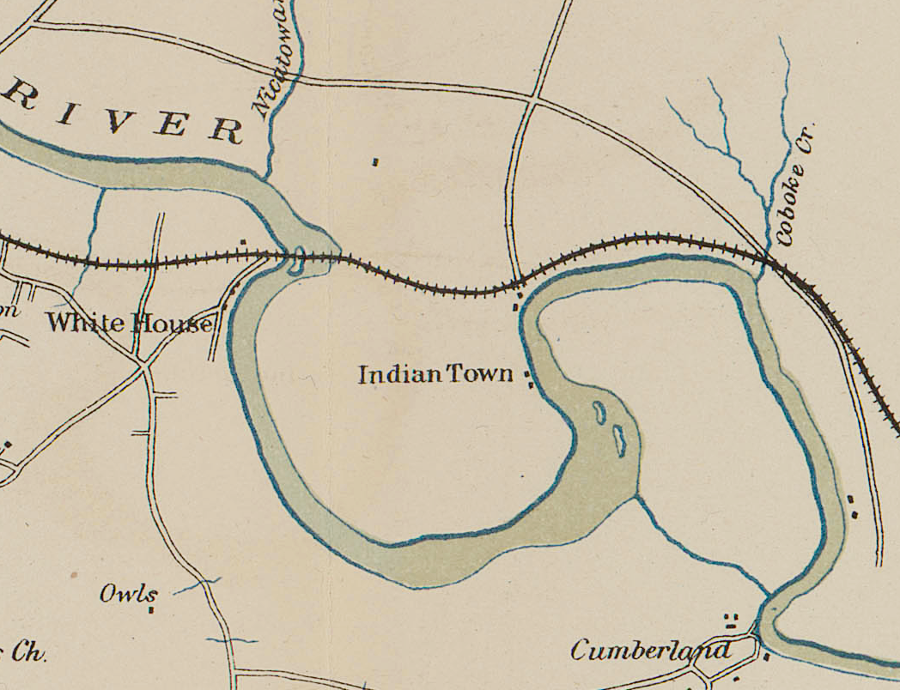

during the Civil War, Union cartographers showed where the Pamunkey were living

Source: US War Department, Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe Showing the Approaches to Richmond and Petersburg (1862)

After the US Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1917, in preparation for entering World War I, Chief George Major Cook of the Pamunkey Tribe led the effort to establish that Native Americans who could not vote in Virginia and were no required to pay taxes were exempt from the military draft.

He was successful in getting a ruling from the Attorney General in 2017 that Native Americans, who until 1924 were not considered to be citizens of the United States, could not be drafted. Some Native Americans in Virginia did volunteer to serve in World War I. That was a personal choice for those men, not an alternative to being involuntarily inducted into the US Army.2

The Pamunkey strongly objected to efforts to erase their identity as Native Americans, particularly after the General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act in 1924. The registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Walter A. Plecker, actively sought to revise birth certificates so people in the state would be classified as either "white" or "colored." The state law defined anyone with any black ancestors as "colored," and Plecker claimed that all Native Americans had at least one drop of black blood. In his eyes, the Pamunkey and members of other tribes should be denied access to whites-only facilities.

The chief of the Pamunkey, George Major Cook, was outspoken in his claims that members of his tribe had never intermarried with blacks, and should not be segregated with them based on the 1924 law. To make his point clear, he claimed:3

By 2019, there were over 400 enrolled members of the tribe, and 85 of them lived on the reservation.4

English colonists never displaced the Pamunkey from their ancestral land on Pamunkey Neck

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Virginia and Maryland As it is planted and Inhabited this present Year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)

The Federal government recognized the Pamunkey in 2016. Formal recognition came through the administrative process of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in the US Department of the Interior. The recognition came over objections by the Black Caucus, which was familiar with the earlier objections of the tribe to being associated with blacks.

That preserved the right to open full-scale gambling casinos (Class III, with roulette wheels and slot machines) under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. In contrast, the six Virginia tribes that were recognized in January 2018, when the US Congress passed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act, agreed to give up any opportunity to open casinos.

In 2019, the General Assembly started the process to authorize state-regulated casino gambling. Legislation in 2019 restricted the potential Norfolk and Richmond markets to just the Pamunkey. The Norfolk City Council then committed to sell to the Pamunkey land next to Harbour Park for a hotel, restaurant, and entertainment venue anchored by a Class III gambling casino. The tribe also acquired land in Richmond.5

Chief William Terrill Bradley in the 1920's

Source: Museum of the American Indian, Chapters on the ethnology of the Powhatan tribes of Virginia (p.243)

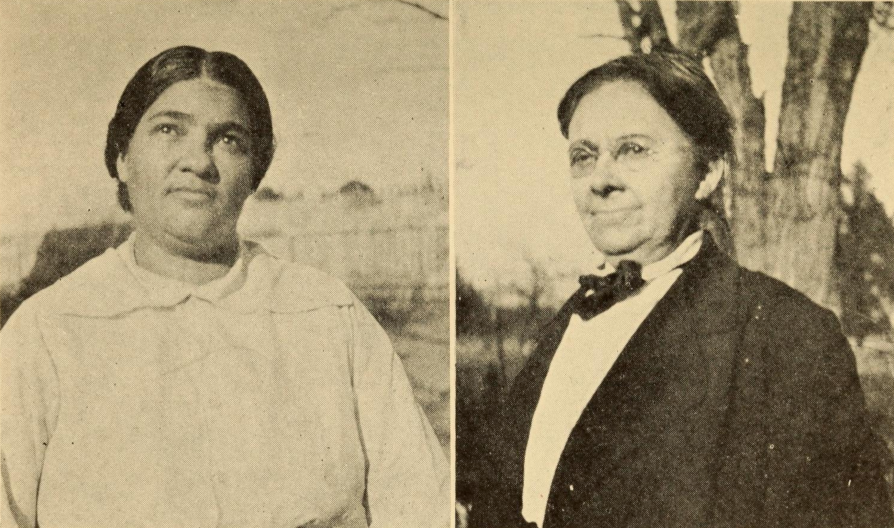

Nannie Miles and Mrs. Allmond in the 1920's

Source: Museum of the American Indian, Chapters on the ethnology of the Powhatan tribes of Virginia (p.247)

Source: American Civil War Museum, Visiting the Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center

Source: City of Hampton, Pamunkey Indian Tribe: Cultural Resource Management

two members of the Pamunkey Indian tribe ceremonially delivered the annual payment of tribute to Gov. Baliles in 1989

Source: Prints and Photographs, Library of Virginia, Indian Tribes Pay Tribute Taxes to Governor Baliles

Source: American Civil War Museum, Union Tooth and Nail: The Pamunkey Indian Tribe and The Civil War in Virginia (June 14, 2016)

Carolina Proprietors produced a map in 1709 that omitted Virginia settlements but highlighted Indian Land, to steer immigrants to Carolina instead

Source: John Carter Brown Library, Map of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (by Joshua Kocherthal, 1709)

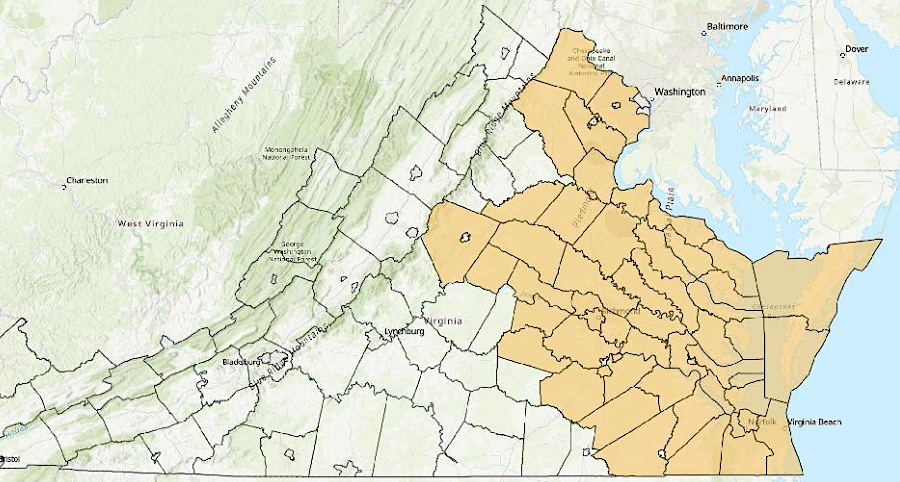

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Pamunkey should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation