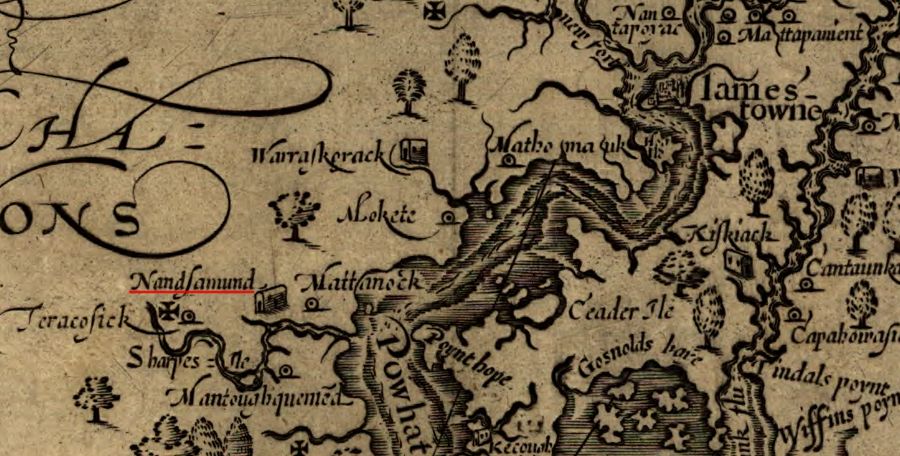

John Smith recorded where the Nansemond lived, south of "Powhatan flu" (James River)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

John Smith recorded where the Nansemond lived, south of "Powhatan flu" (James River)

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

When English colonists arrived in 1607, they discovered the Nansemond tribe living on the Nansemond River in different villages near modern Chuckatuck. Canoes made the river a transportation corridor, not a barrier to travel.

The Algonquian-speaking Nansemond were part of Powhatan's paramount confederacy. They were one of the over thirty tribes within his territory (Tsenacommacah), and they were on the edge. Algonquian-speaking Chowanoac and Weapemeoc/Yeopim living to their south were outside of Powhatan's control. "Chowanoac" is Algonquian for “people at the south."

The Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway and Meherrin, living to their west, were also outside of Tsenacommacah.1

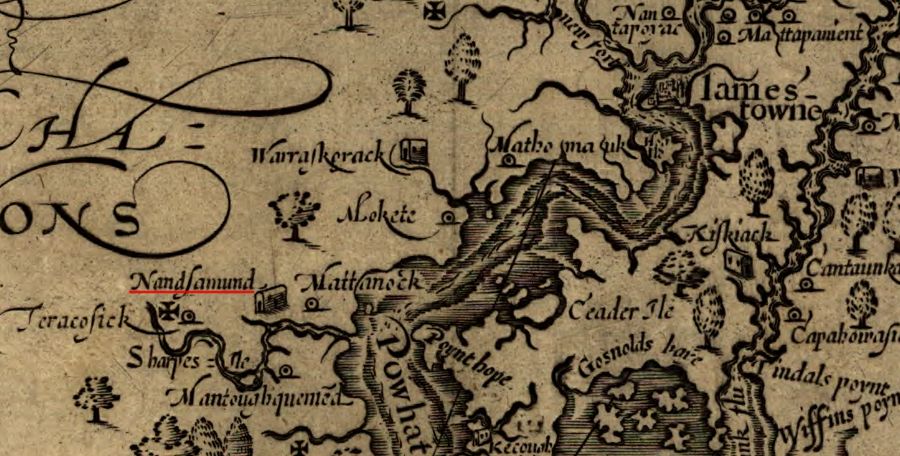

Around the time the English arrived to settle at Jamestown, the Nansemond men may have repopulated the territory occupied by the Chesapeake east of the Elizabeth River. Powhatan had expanded Tsenacommacah by seizing their land and killing/moving the Chesapeake weroance and other key leaders. The English colonist William Strachey later reported that the attack was done in response to a warning from Powhatan's priests that an empire from the east would threaten his paramount chiefdom.2

It would be out of character for Powhatan to order the slaughter of all the Chesapeake women and children. They may have been moved away and incorporated into a different tribe already under Powhatan's control, with him ordering whole families of a tribe he already controlled to move into that territory. More likely, Powhatan sent men from his nearest allies, the Nansemond, to re-occupy the former Chesapeake towns and recreate what the English colonists described as the separate Chesapeake tribe.

the Nansemond may have repopulated the territory of the Chesapeake just before the English arrived in 1607

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

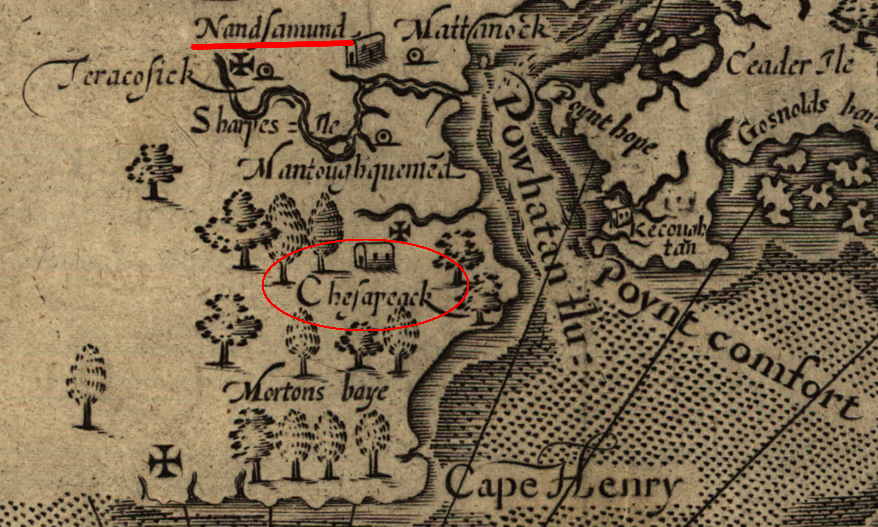

John Smith and Christopher Newport discovered that the Nansemond "weroance" lived on Dumpling Island. That island was also the site of their temple. There may have been as many as 1,500 members of the tribe when the English first arrived. Today, there are approximately 200.

The name "Dumpling Island" apparently was created by the English settlers, and is not derived from whatever name of the place was used by the Nansemond. Modern speculation is that the always-hungry colonists thought the island looked like an English dumpling. An alternative possibility is that the island was recognized as the source of corn that had been seized from the Nansemond to feed the colonists.3

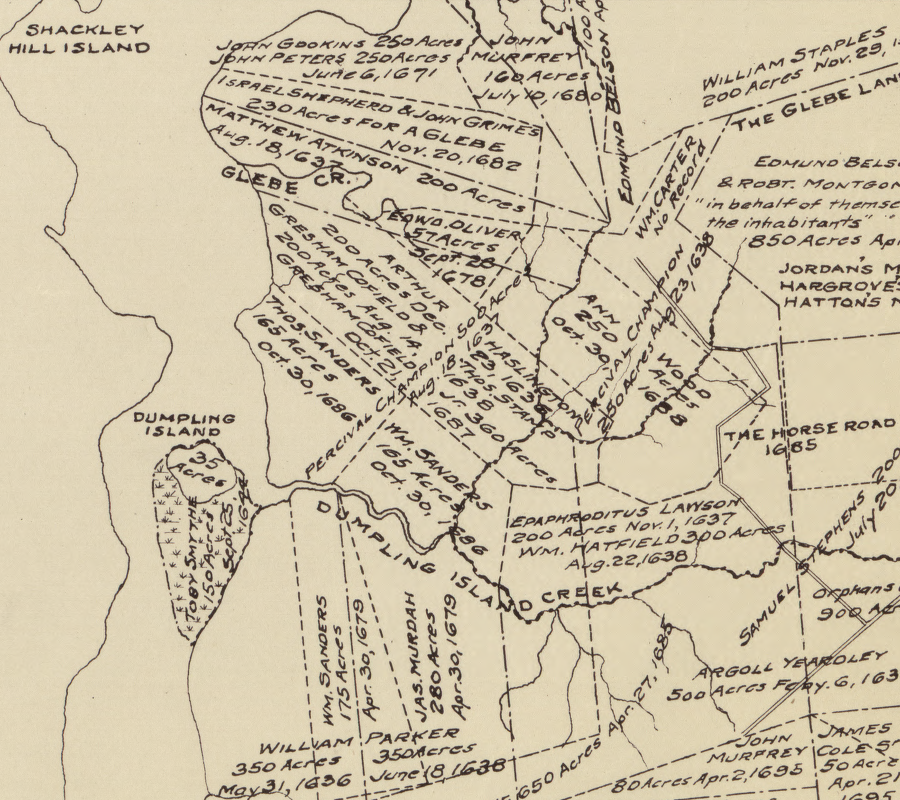

English colonists ignored Native American land claims and issued grants to land in Nansemond territory, including Dumpling Island

Source: Library of Congress, The lower parish of Nansemond County, Va. with adjoining portions of Norfolk County : Elizabeth City Shire 1634, New Norfolk County 1636, Upper Norfolk County 1637, Nansemond County 1642

After the ships of the Third Supply arrived in 1609, John Smith refused to cede authority to the officials who made it across the Atlantic Ocean, taking advantage of their leadership vacuum after the flagship Sea Venture wrecked on Bermuda and stranded the man officially designated by the Virginia Company to act as governor, Sir Thomas Gates.

Smith asserted that he remained as president of the council. He solved the conflict over control in part by directing some of the new leaders to create settlements away from Jamestown. In those new places away from Smith, rivals could be in command. They could also find new food sources to feed new colonists away from Jamestown.

Smith send George Percy and John Martin with 60 colonists to create a new English settlement on the Nansemond River. Most men walked along the southern bank of the James River to the Nansemond River, while Percy and Martin sailed there in a small ship.

After reuniting, two colonists were sent to Dumpling Island to start negotiations. The English wanted to trade copper and other commodities for a space to live and food. The weroance refused to abandon the site of his tribe's temple, with the remains of former leaders, and the main grain storage bins.

After the English decided that the two negotiators had been killed, they tried to seize land by force. George Percy later described discovering how the colonists attacked the Nansemond and sacked their town on Dumpling Island:4

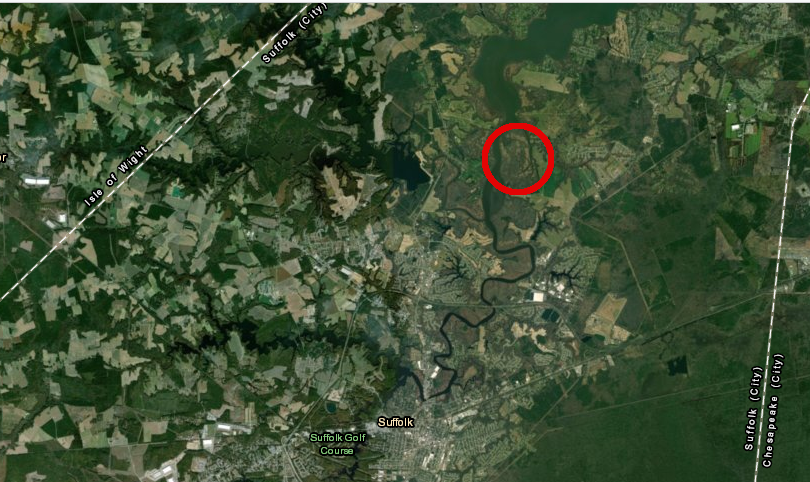

Dumpling Island in the Nansemond River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1611, Sir Thomas Dale considered using the Nansemond lands to found a new settlement that would eventually supersede Jamestown. Dale ultimately chose to locate the new settlement, which he called Henricus, further upstream. Instead of the Nansemond, the Arrohateck who lived near the mouth of the Appomattox River were displaced.5

The First Anglo-Powhatan War ended in 1614, when the paramount chief Powhatan agreed to peace and allowed his daughter Pocahontas to marry one of the "Tassantassas." The Nansemond joined Opechancanough in the 1622 Second Anglo-Powhatan War, and again the English burned their towns and destroyed their corn. To avoid the colonists, Nansemond moved away from the main stem of the Nansemond River.

In 1638, colonist John Bass married the daughter of the Nansemond weroance. That marriage established the community of "Christianized" Nansemonds, separate from the band of "Reservation" Nansemonds. The last member died in 1806, after the 300 acres of their last reservation on the Nottoway River was sold in 1792.6

the remaining presence of the Nansemond was recorded in a 1670 map of the Nansemond River

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

Nansemond children were sent to the Indian School at William and Mary College, housed in the Brafferton building.7

The Nansemond Indian Tribal Association has been recognized officially by the state of Virginia since 1985. Federal recognition was approved by the US Congress in 2018, when it passed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017. At that time, the tribe had 300 members.8

Dumpling Island, today

Source: US Geological Survey, Chuckatuck, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2016) and Google Maps

In 2010, City of Suffolk agreed to transfer 71 acres in Lone Star Lakes Park near Chuckatuck to the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association. The site had been used to mine calcium-rich marl and ship it to South Norfolk for production of cement since the 1920's. Mining stopped in 1971. The Lone Star Cement Company determined it would not be cost-effective to upgrade the furnaces that heated the marl to make cement in order to meet air quality standards.9

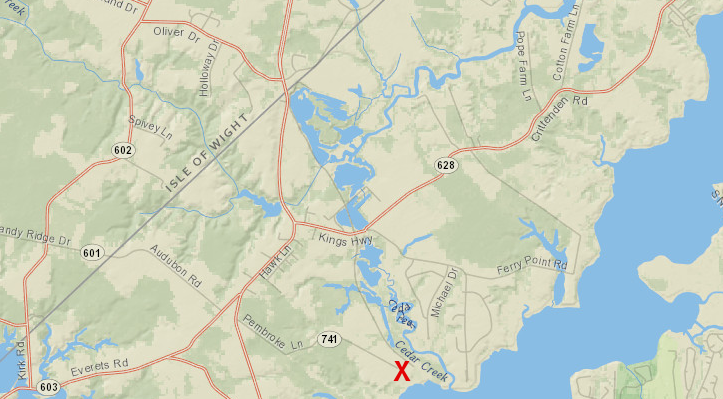

in 2013, the City of Suffolk deeded 70 acres of the former Lone Star Cement Company site to the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The tribe planned to build a recreation of a historic palisaded village with a longhouse, school, museum and cultural park. Constructing Mattanock Town was projected to cost $5-8 million. The city stipulated that the project had to be completed in five years, or the land would revert back to the city.10

Boy Scouts helped construct trails and get five longhouses started, but finding the funding was a challenge. The tribe did not own the land, so it could not be used as collateral for a loan and donors had to consider the possibility that ownership of the proposed Mattanock Town would revert to the city.

In 2013, when the deed transferring the land was signed, Nansemond Chief Earl Bass said "It's like a weight lifted." Three years later, he projected an extension of the five-year deadline would be necessary. Describing the 2018 deadline, he recycled his earlier phrase: It's like a weight hanging over our heads.11

By 2022, the dreams of attracting 50,000 visitors a year had faded and Chief Bass was correct in the need for an extension. The tribe ended up owning over 500 acres of the other side of the Nansemond River in 2022, while the effort to acquire title to the 71 acres in Lone Star Lakes Park was still underway.

In 2024 the Suffolk City Council decided to waive the requirement to recreate Mattanock Town, and transferred the land to the tribe. The parcel included 21 acres of tidal wetlands. The transfer include a conservation easement to protect environmental resources, and a requirement that the tribe provide public walking trails and boat access to the Nansemond River. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science developed a conservation plan for the site.

The tribe's Assistant Chief Dave Hennaman commented after the decision was announced:12

the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association planned to reconstruct a palisaded town near Chuckatuck

The historical territory of the Nansemond became an issue in 2019. The Pamunkey proposed to build a gambling casino and hotel complex on the Elizabeth River in Norfolk, taking advantage of their status as a Federally-recognized tribe with rights under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. The proposal included having the US Bureau of Indian Affairs take land next to Harbor Park into trust and add it to the Pamunkey Reservation.

The Nansemond objected to the Pamunkey claim that the Elizabeth River was within their traditional territory. The Nansemond asserted they had a greater claim to the former Chesapeake territory, now included within the cities of Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and Chesapeake. The Nansemond chief notified the mayor of Norfolk that:13

One possible outcome was for the Pamunkey and Nansemond to negotiate a deal. If the Pamunkey agreed to share enough profits to establish Mattanock Town, the Nansemond might support the casino proposal. The Pamunkey chief, Robert Gray, said in 2019:14

The Commonwealth of Virginia had previously identified the Nansemond (not the Pamunkey) as the closest related tribe to the now-extinct Chesapeakes. When the Virginia Department of Historic Resources reburied 64 skeletons in 1997 that had been excavated from Great Neck in Virginia Beach, before a subdivision was constructed in the 1970's and 1980's, the state agency partnered with the Nansemonds.

Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, "cultural affiliation" is the basis for determining where to repatriate artifacts and burial remains. The Nansemond adopted the remains and ceremoniously re-interred them at First Landing State Park on April 26, 1997.15

the Nansemond helped rebury remains that had been excavated from the Chesapeake town on Great Neck

Source: Library of Congress, Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta (by Thomas Hariot, 1590)

In 2022, the Nansemond Indian Nation acquired 508 acres a Cross Swamp. The family which owned it originally contacted Ducks Unlimited to arrange for a sale. The Virginia Outdoor Foundation then assembled different funding sources that provided $1.1 million to acquire the property and have it donated it to the Nansemond Indian Nation, with a conservation easement to prevent development.

Cultural anthropologist Helen Rountree commented on the first land that the Commonwealth of Virginia considered to be legally owned by the Nansemond:16

The Nansemond complained in 2023 that TC Energy had failed to consult with the tribe regarding plans to expand a pipeline built in the 1950's that crossed ancestral lands in Suffolk and Chesapeake. The tribe asserted that the original pipeline had impacted 13 archaeological and cultural sites. As part of the analysis for the proposed expansion, called the Virginia Reliability Project, the Nansemond Indian Nation asked for an ethnographic analysis to identify more historic properties and cultural sites nearby.17

On July 9, 2024, the Nansemond Indian Nation removed an abandoned vessel from the shoreline near Mattanock. Restoring the natural character of the area was facilitated by a $26,000 grant from the Virginia Marine Corps Commission's Abandoned or Derelict Vessel Program.18

The tribe has participated in the Chesapeake Bay Foundation's Oyster Gardening Program since 2020. Each year oysters are planted in Nansemond River tributaries such as Chuckatuck Creek and on reefs created by the Nansemond River Preservation Alliance (NRPA). The vice chair of the Nansemond Tribal Council said:19

the Nansemond Indian Nation acquired 508 acres at Cross Swamp in 2022

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Chuckatuck, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2022)

Nansemond warriors adopted iron hatchets after English colonists provided them as a trade item

Source: Watts, Nansemond Indian Nation Pow Wow - Suffolk Virginia; Nansemond Indian Nation, Annual Pow Wow

Nansemond warriors adopted iron hatchets after English colonists provided them as a trade item

Source: Watts, Nansemond Indian Nation Pow Wow - Suffolk Virginia

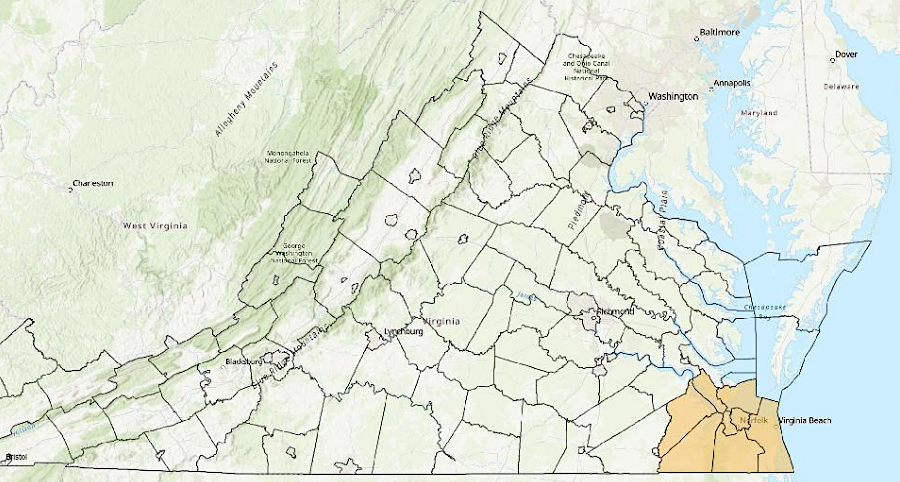

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Nansemond should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation