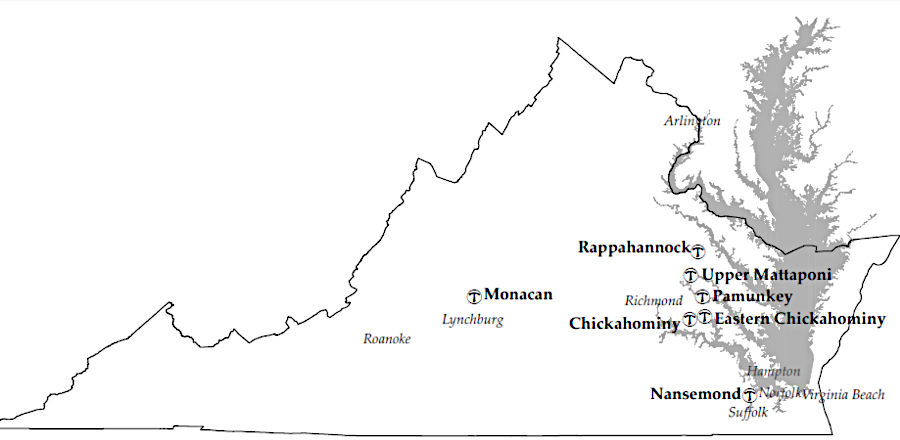

seven Virginia tribes have obtained Federal recognition

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federally-Recognized Tribes in EPA's Mid-Atlantic Region

seven Virginia tribes have obtained Federal recognition

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federally-Recognized Tribes in EPA's Mid-Atlantic Region

Virginia has a state-controlled process that has granted official recognition to 11 tribes. Recognition by the Federal government is a totally separate process from state recognition. The 1924 Indian Citizenship Act finally established that all Native Americans born in the United States were automatically citizens, but state laws continued to restrict voting rights until 1948. Local practices restricted access to the ballot into the 1960's.

Source: Ohio History Connection, The 1924 Indian Citizenship Act

Virginia's tribes were conquered by English colonists long before the Federal government was created in 1788. British officials in North America and colonial leaders negotiated numerous deals with different tribes, most of which involved the cession of land claims to the colonists.

The first treaty between a tribe and the Continental Congress was a treaty of peace, friendship and alliance signed in 1788 with the Lenape (Delaware). With passage of the Indian Appropriations Bill in 1871, the US Congress ended the use of treaties to define Federal-tribal relationships. Tribes lacked the power as autonomous governments to enforce treaty terms, which were routinely ignored by the US Government.

The US Congress enhanced the authority of the legislative branch when it eliminated the role of the president in negotiating treaties. Since 1871, bilateral agreements approved by both houses of Congress have defined new government-to-government relationships with the tribes.

Because Virginia's Native Americans were suppressed by colonists before creation of a national government, there are no Federal treaties and no Federal reservations involving the Virginia tribes. As one reporter noted in 2010 about the Native Americans in Virginia:1

In 2016, the 200-person Pamunkey tribe succeeded in getting Federal recognition via the administrative process of the US Department of the Interior. In January 2018, the US Congress passed and President Trump signed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. That occurred 18 years after the legislation was first introduced.

The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act was used to bypass the administrative process managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the US Department of the Interior. That bill granted Federal recognition, through legislative action, to the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond tribes in Virginia. There were 4,400 members of those six tribes affected by the new law.

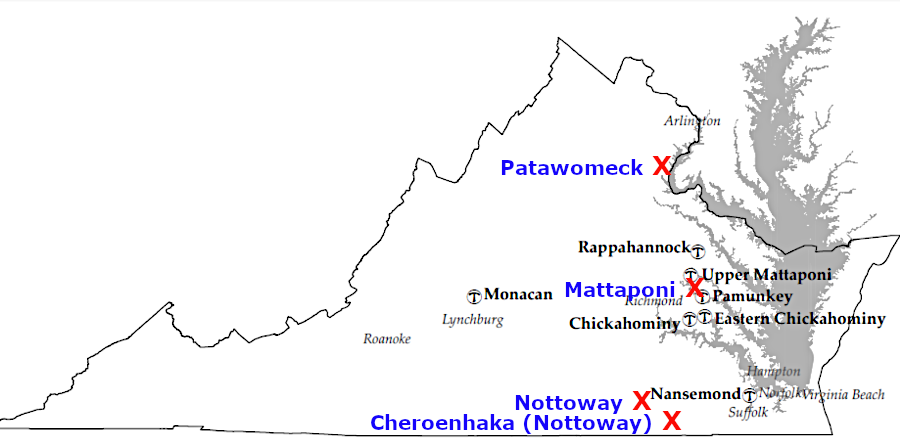

The final bill passed by the US Congress in 2018 omitted the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. They chose to pursue the administrative rather than the legislative process to obtain Federal recognition. Though the Nottoway, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), and Patawomeck received state recognition by the Virginia General Assembly in 2010, the Virginia delegation in the US Congress did not add those three tribes to the various versions of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia bill.2

The Pamunkey tribe first requested formal Federal recognition through the administrative process in 1982, and were later joined by several tribes. "Recognition" would establish a government-to-government relationship between each tribe and the United States, making members of the tribe eligible for funding and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the US Department of the Interior.

Their efforts received heightened attention during the 400th commemoration of the settlement of Jamestown in 2007, but did not result in Federal recognition. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey still continued to follow the administrative process. Those two tribes had the best documentation, dating back to a reservation established by treaty in 1646, and were most likely to meet the review requirements. Other tribes in Virginia had less documentation of their persistence since disruption in colonial times. Six of them chose to pursue a legislative remedy, the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act.

The Mattaponi application remained frozen in the administrative review conducted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and that tribe was not included in the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. Other tribes recognized by the state but not the Federal government, in addition to the Mattaponi, are the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Nottoway, and Patawomeck.

In the 2013 and 2015 sessions of the US Congress, the House of Representatives had approved the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act but the US Senate never voted on the bill. Individual senators apparently placed a "hold" on the bill, blocking it from being considered.

In May 2017, Rep. Rob Wittman obtained unanimous approval by the House of Representatives. On January 11, 2018, Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner managed to trigger a vote. Though the Washington Post said they "forced a surprise vote on the bill by unanimous consent Thursday afternoon with no guarantee it would pass," the senators had arranged in advance for leaders of each tribe and the Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life to be present for the vote. President Trump signed it on January 29, 2018.3

leaders of the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Monacan, and Nansemond tribes, Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life, and Senators Kaine and Warner in 2018

Source: Senator Tim Kaine, Virginia Tribal Chiefs Joined Kaine and Warner in Senate Chamber for final vote

The bill was named after Thomasina Elizabeth Jordan (Red Hawk Woman), who died in 1999. She was a member of the Alexandria Republican City Committee, and the first American Indian to serve in the Electoral College (in 1988). She was appointed chair of the Virginia Council on Indians by Republican governor George Allen, and re-appointed by Republican governor James Gilmore. She was an effective and well-respected advocate when seeking support from the General Assembly for Native American programs.4

The lack of Federal recognition has limited the ability of Virginia tribes to rely upon Federal protections for cultural heritage. They have been unable to access funding available to recognized tribes in social programs for education, housing and health care, which could amount to $10-12 million/year. The Congressional Budget Office projected that the government would spend $67 million over the 2018-2022 period if the six Virginia tribes were granted recognition.

In particular:5

The administrative recognition process for Federal recognition is based in the Executive Branch. It relies upon Bureau of Indian Affairs (Department of the Interior) regulations issued in 1978, after lawsuits over fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest and land ownership in Maine.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) description of the Federal recognition process included these answers to Frequently Asked Questions:6

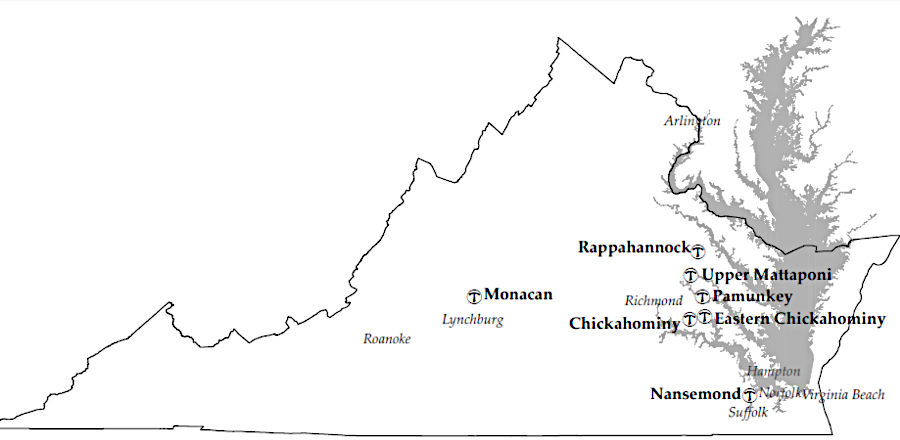

until the 2015 decision on the Pamunkey Tribe, there were no Federally-recognized tribes within Region 3 of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Protection in Indian Country

The administrative procedures of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 25 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 83, require extensive documentation of continuous tribal existence throughout time. As of 2015, the Federal government had recognized 566 tribes, but roughly 400 other groups claimed tribal status. The Federal administrative recognition process was so slow that it would require over 100 years before the backlog of petitions in 2015 would be eliminated.7

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi chose to seek Federal recognition through the administrative recognition process, anticipating that they could meet the historical documentation required by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Executive Branch officials recommended consistently that Virginia tribes must go through the administrative process to obtain recognition. The director of the Office of Federal Acknowledgement at the Department of the Interior objected to the Thomasina Jordan Indian Tribes Of Virginia Federal Recognition Act in 2006, since a decision by Congress would allow the Virginia tribes "to avoid the scrutiny to which other groups have been subjected."8

The Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Monacan, Nansemond, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi chose a path that was not included in Public Law 103-454, the Federally Recognized Indian Tribe List Act. Those six Virginia tribes requested special legislation by the US Congress to grant them Federal recognition.

Their basic argument was that social repression since the colonial period had required tribal communities to live in the shadows, minimizing their appearance in historical records. Many county records were burned in the Civil War, removing proof of tribal existence and continuity in the 1700's and 1800's.

More recently, state and local government repression in the early 1900's had eliminated the documentation required by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to show continued persistence as a distinct tribe. The tribes could not meet the documentation standards required by the Bureau of Indian Affairs because of government action, so a government remedy was appropriate.

Seeking direct legislative action was not a new idea. As far back as 1923, Rappahannock chief George Nelson had appealed directly to Congress to appropriate $50,000 to establish an Indian school in Virginia. After the General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, the registrar of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics suppressed, modified or purged historical records to eliminate the ability of anyone to claim to be "Indian." Virginia refused to establish any form of "mulatto" status for non-whites who under segregation might claim some privileges beyond the constrained rights of people classified as "Colored."

Dr. Walter Plecker proclaimed in 1940:9

Starting in the 1990's, both Republican and Democratic legislators from Virginia have sponsored bills for Federal recognition of Virginia tribes. Legislation was approved by the House of Representatives several times, but the US Senate never voted approval until 2018.

The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act was introduced first in 2007. The bill authorized the Secretary of Interior to take "into trust" as Federal reservations lands owned by those tribes within defined geographic boundaries, and bypassed the administrative process to legislatively grant Federal recognition to the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond tribes.

The Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Nottoway, and Patawomeck tribes had bypassed Virginia's administrative process for state recognition, managed by the Virginia Council on Indians. That council did not endorse the Nottoway request for recognition, and the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) and Patawomeck never submitted a petition to the council for state recognition.

The three tribes went directly to the General Assembly in 2010. Wayne Newton claimed Patawomeck heritage and drew media attention when testifying in support of recognition. The state legislature chose to ignore the administrative process and passed a law that granted state recognition to the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Nottoway, and Patawomeck. In response, the Virginia Council on Indians then stopped meeting. It was dissolved in 2012, ending the administrative process for state recognition of Native American tribes.10

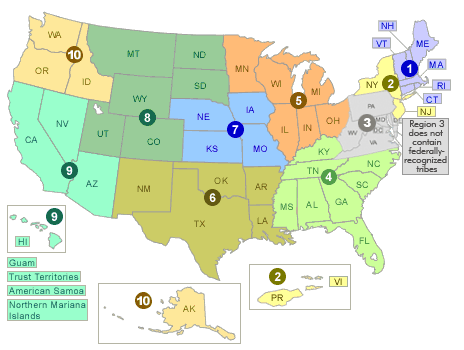

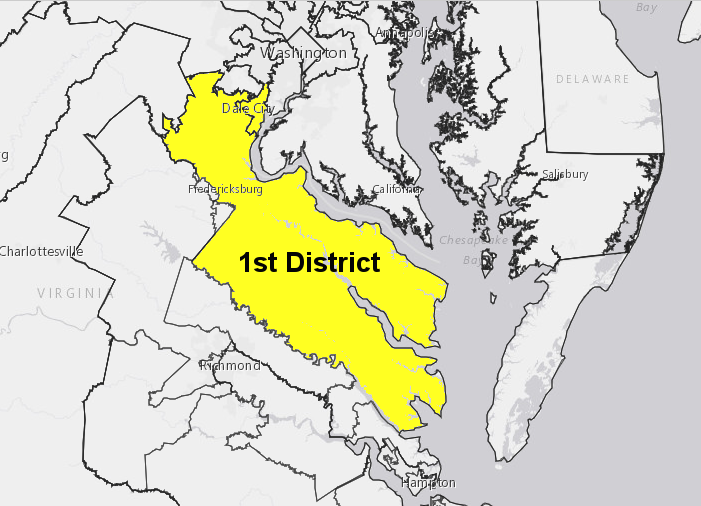

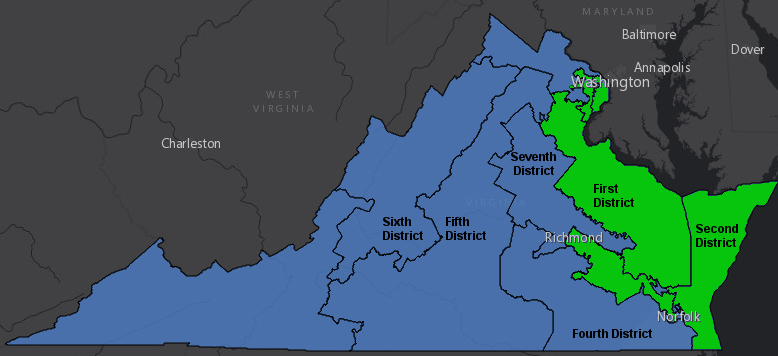

Support for Federal recognition of the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Monacan, and Nansemond tribes has been bipartisan in Virginia. In the House of Representatives, the 2015 and 2017 chief sponsor of H.R.872 was a Republican, Rep. Rob Wittman. His 1st District included much of the territory in Tidewater Virginia once controlled by Powhatan's paramount chiefdom.

Rep. Rob Wittman's district included much of the territory in Tidewater Virginia once controlled by Powhatan's paramount chiefdom

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2015 and 2017 Rep. Wittman's bill was co-sponsored by a fellow Republican from the 2nd District, which included the Eastern Shore and Virginia Beach. Other co-sponsors in the House were the Democratic Representative from the 3rd District (which included much of the James River watershed downriver from Richmond) plus two Democratic Representatives representing the 8th and 11th districts in Northern Virginia. The Democratic US Senators from Virginia supported a parallel recognition bill in the US Senate.

Four Republican members who represented Congressional districts affected by recognition of those six tribes were not co-sponsors at the time of the 2015 hearing. The Representatives from the 4th and 7th Districts (which included territory once controlled by the Nansemond, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi) and the Representatives from the 5th and 6th Districts (with territory once occupied by the Monacan) declined to co-sponsor the bill.11

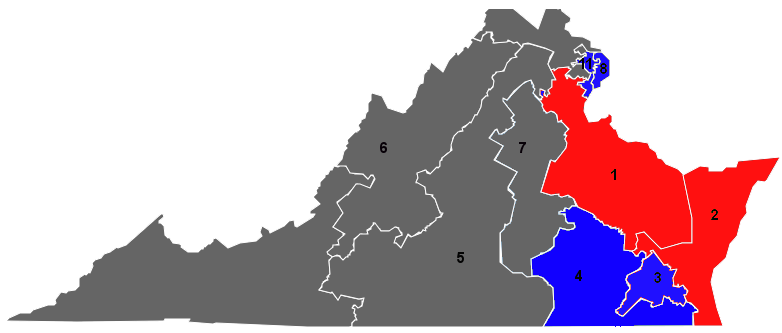

the US Representative from the 1st District sponsored a bill in 2015 for recognizing six Virginia tribes and the US Representatives from the 2nd, 3rd, 8th, and 9th districts joined as co-sponsors (area colored green), but the US Representatives from four other Virginia districts that would be affected (4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th) did not join in co-sponsoring H.R.872

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

There was opposition to recognition based on concerns that other, unqualified groups across the country would be encouraged to avoid the Bureau of Indian Affairs process. There was also opposition based on racial identity and economic rivalry.

The Department of the Interior announced in early 2014 that the Pamunkey tribe with 203 members had "met all seven mandatory criteria for Federal acknowledgment." The Congressional Black Caucus and MGM organized last-minute objections.

Pamunkey tribal law had allowed new spouses who married a tribal member to live on the reservation, but not if the spouse was black. Until 2012, the law said:12

That restriction was a relic of the early 1900's. Virginia adopted numerous "Jim Crow" laws to segregate blacks from whites, and starting in the 1920's state officials tried to classify Native Americans as "colored." In response, the Pamunkey sought to heighten awareness of their distinctive Native American heritage and to minimize public perception that there was any association with non-whites.

Rep. Frank Wolf, who represented the 10th District in Northern Virginia between 1981-2015, was an influential opponent motivated by the gambling issue. He claimed Federal recognition could lead to casino gambling authorized under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, even though tribes recognized after 1988 must comply with state laws and Virginia bans such gambling. Rep. Wolf did not block passage in the House of Representatives, but his opposition may have led to the bills being stalled by "holds" in the Senate.

Rep. Wolf stated that his objections would disappear if the Virginia tribes would accept Federal legislation that permanently banned casino gambling on tribal lands, within or outside of the boundaries of a reservation and independent of any future loosening of Virginia's state restrictions on gambling:13

In 2014, Rep. Wolf was no longer in office. Instead, the MGM corporation objected to Federal recognition of the Pamunkey tribe.

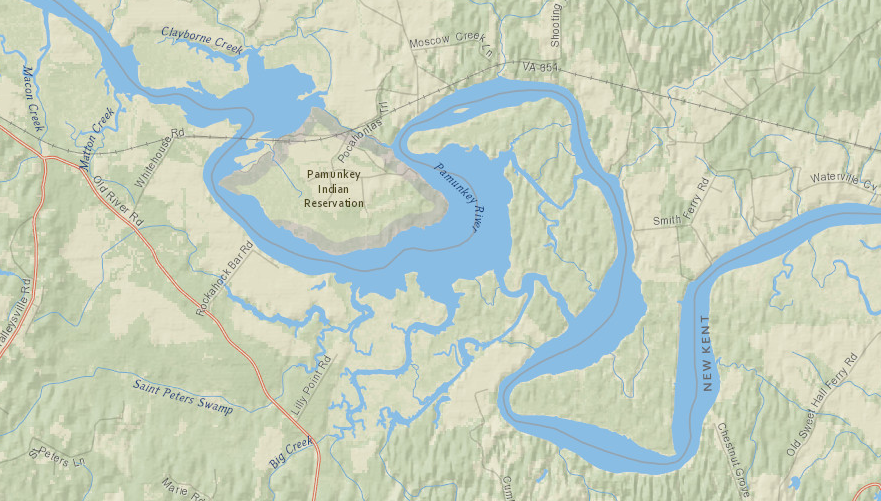

Pamunkey Neck was reserved for Native Americans after the Anglo-Powhatan wars in the 1600's

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

MGM held a State of Maryland license to operate the gambling casino at National Harbor on the Potomac River. The Pamunkey occupied a 1,200-acre reservation, the oldest in Virginia, halfway between Hampton Roads and Richmond in King William County. It feared that Federal recognition of the Pamunkey tribe would lead to a competing casino on the Pamunkey reservation.

Late in 2015, the Washington Post revealed that the tribe was negotiating with a casino developer as the Department of the Interior was making the final decision on Federal recognition. The chief and council prepared a new tribal budget with costs increasing from $30,000/year to $500,000/year. No source of new funding was documented to provide a new $100,000/year salary for the chief of the tribe and a $25,000/year salary for each of the six council members. The Pamunkey responding by ousting the chief from his elected position.

The only logical source for funding the proposed increase in the tribal budget was a corporation making a speculative investment, planning to shape a future decision to allow casino gambling on the Pamunkey reservation. That could have been MGM, covering all the bases. As one member of the tribe noted:14

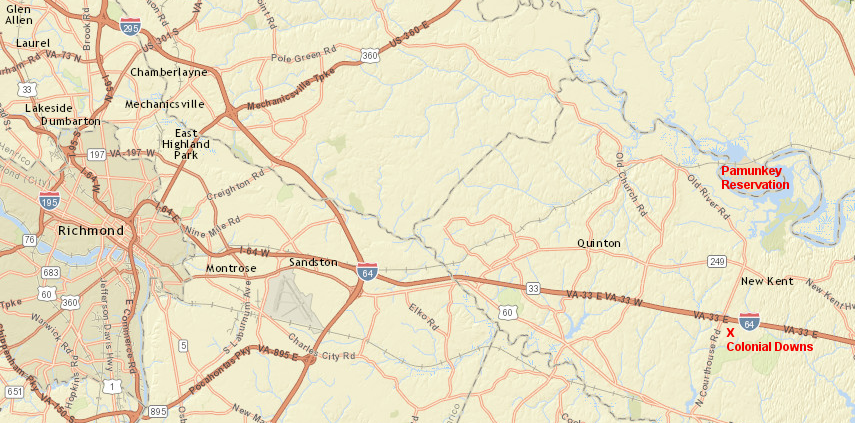

Though the tribe conceivably could negotiate with Virginia and Federal officials and ultimately open a casino on the Pamunkey River, there is no guarantee that the site could attract enough customers to be profitable or compete with MGM at National Harbor. The Pamunkey reservation is a 40-minute drive from I-64, much of it on poor 2-lane roads.

Colonial Downs racetrack, on an I-64 interchange halfway between Hampton Roads and Richmond, provided a more-accessible location for gambling, but it was unable to attract enough customers and shut down in 2014. The Colonial Downs racetrack had a monopoly for horse race gambling in Virginia. It was the only racetrack in the state with an unlimited pari-mutuel license authorizing gambling throughout the year.

Despite being right on I-64, gambling at the racetrack was not popular enough to draw enough customers out of the urban areas. Colonial Downs generated most of its revenue from Off Track Betting (OTB) kiosks highlighting races at tracks in other states.

The profits from OTB operations did not offset the costs of hosting races at Colonial Downs. In 2014, the racetrack surrendered its unlimited pari-mutuel license and closed the OTB facilities. If a racetrack with offsite betting could not draw enough customers to stay in business, the business case for a casino at the Pamunkey reservation was even thinner.

the reservation of the Pamunkey Tribe is north of I-64, and visitors must drive an additional 45-60 minutes longer on 2-lane roads than is required to reach Colonial Downs

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

MGM may have anticipated the tribe could partner with a competing gambling corporation and open a casino at a location more convenient for customers than the reservation on the Pamunkey River. The Federal government has authority to designate additional property - even Colonial Downs - as part of the Pamunkey Reservation. In what may have been MGM's worst-case scenario, the tribe might arrange a business deal with a rival, a political deal with the Virginia General Assembly, and open a tribal gambling casino at the site of the racetrack. A Virginia casino on I-64 could reduce the number of customers willing to drive to MGM's casino's in Maryland.

Opposition to Federal recognition of the Pamunkey Tribe came from non-gambling sectors as well. In 2015 the Virginia Petroleum, Convenience and Grocery Association testified in opposition. It feared that convenience stores located on reservations would not charge state tobacco, gasoline, or sales taxes.

At the time, the state excise tax was 17.5 cents/gallon for gasoline. Eliminating the need to pay that tax could allow a gas station on the reservation to offer lower prices and undercut gas stations nearby. The lobby group portrayed the option of a sovereign Native American tribe to set and collect its own taxes on reservation lands as "tax evasion."15

The US Department of the Interior continued to support recognition of the Pamunkey tribe. The regulations for considering evidence of historical tribal integrity were revised, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs announced on July 2, 2015 that the Pamunkey tribe had met the criteria because it had:16

The decision was not final. In October, 2015, a non-government organization called Stand Up for California filed an appeal with the Department of the Interior to block the decision to recognize the Pamunkey tribe. Stand Up for California, which opposed gambling on Indian lands, resubmitted the same arguments it had made during the administrative process. Those echoed the concerns of MGM, as well as moral opposition to gambling.

During the time required for the Interior Board of Indian Appeals to consider the appeal, the tribe was unable to access any Federal programs that might have been made available after recognition. In early 2016, the Federal agency rejected the appeal and confirmed recognition of the Pamunkey tribe. Following it, Preservation Virginia repatriated to the Pamunkey the "frontlet" (a piece of silver jewelry) given to Queen Cockacoeske after she signed the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation.17

the silver frontlet given to Queen Cockacoeske after she signed the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation was repatriated to the Pamunkey in 2017

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, Cockacoeske

The 2016 rejection by the Interior Board of Indian Appeals of the Stand Up for California request had no impact on the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Rappahannock, Monacan, Nansemond, and Upper Mattaponi tribes process for legislative recognition. The rejection did clear the way for the Mattaponi, with their own reservation, to pursue their case for administrative recognition like the Pamunkey.

In September, 2016, when the Natural Resources Committee in the US House of Representatives approved the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act, Rep. Wittman from the 1st District commented:18

Once again, committee approval occurred late in the second session of the Congress, just before the election in November. There was not enough time for action by the full House and the Senate and again the process for legislative recognition fell short of closure.

In 2017, the two US senators and five Representatives from Virginia introduced the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017, starting the process for legislative recognition once again. The 2017 bill also excluded the Mattaponi. Senator Kaine noted several years later that recognition by itself did not erase centuries of mistreatment and misunderstanding:19

Governor Terry McAuliffe, highlighting Federal recognition of the Pamunkey at the 2016 treaty ceremony

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth

The 2017 bill was also bipartisan, though a court-ordered redistricting of Congressional boundaries for the 2016 election changed which tribes were represented by the members of the US House of Representatives. Much of the territory once controlled by the Chickahominy and the Eastern Chickahominy moved from the 1st to the 2nd District. The same redistricting shifted the ancestral homeland of the Rappahannock and Upper Mattaponi from the 7th into the 1st District.

Rep. Rob Wittman (1st District) introduced the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 in the US House of Representatives, and fellow Republican Rep. Scott Taylor (2nd District) co-sponsored it. The Republican in the 7th District, whose district lost most of its territory east of the Fall Line and in 2017 represented even less of what was once Tsenacommacah, did not co-sponsor the bill in 2015 or in 2017.

Democrats in Northern Virginia supported the bill even though it affected tribes who had never lived in the 8th or 11th districts, to show support for Native Americans.

Before the 2016 redistricting, the 3rd District had included significant portion of Tsenacommacah once controlled by Powhatan. After the redistricting, the home of the Nansemond tribe shifted from the 4th District into the 3rd District. In 2017, the Democrat representing the 3rd District renewed his previous support for recognition and co-sponsored the bill.

The redistricting resulted in a Democrat replacing a Republican as the US Representative for the 4th District. That district still included some territory once occupied by the Nansemond, but the location where the tribe was developing a cultural center had shifted to the 3rd District. The new Democrat representing the 4th District, Rep. Donald McEachin, did not initially co-sponsor the recognition bill in 2017 but did sign on several weeks later.

The redistricting did not affect the 5th and 6th Districts, home to the Monacan tribe. The newly-elected Republican serving the 5th District and the re-elected Republican incumbent in the 6th District both declined to co-sponsor the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017.20

In 2018, the US Congress approved the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. Both the House of Representatives and the US Senate were controlled by Republicans, and President Trump belonged to that party as well. Separate from all the justifications, a political reason for finally passing the bill may have been a desire to assist Rep. Rob Wittman's re-election effort. His office was able to issue a news release titled "President Signs Virginia Tribes Recognition Bill Authored by Wittman into Law."

In October 2018, before the election, Rep. Rob Wittman was the only member of Congress during an intertribal celebration of Federal recognition at Werowocomoco. The two Democratic senators and the Democratic governor sent other representatives, allowing Rep. Wittman to gain attention for getting the recognition bill passed.

That event included the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Chickahominy Eastern Division, Monacan, Nansemond, Rappahannock and Upper Mattaponi tribes. The Mattaponi and the other tribes which still were not "recognized" by the Federal government, including the Patawomeck in Stafford County (part of the First Congressional District of Rep. Wittman), did not participate.21

Rep. Wittman did win re-election in November. Democrats won three other districts that had been held by Republican members of Congress in 2018. In the Second and Seventh districts, both adjacent to the First District represented by Wittman, the Republican candidates were defeated by narrow margins.

Passage of the tribal recognition act may not have gained Rep. Wittman many votes from the small Native American population in his district, but it did enable him to claim during his campaign:22

Republicans in the 1st and 2nd districts, and Democrats in the 3rd, 4th, 8th, and 11th districts, supported legislative recognition of six Virginia tribes in 2017

Source: ESRI, Virginia Public Access Project

The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act gave Federal recognition to six tribes through the legislative process, and the law included a specific prohibition against those six tribes opening gambling establishments. When three Virginia members in the US House of Representatives introduced the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia Federal Recognition Act in 2023, they also included a prohibition of that tribe (if Federally recognized) taking advantage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

The administrative recognition process used successfully by the Pamunkey included no such prohibition. Two years after receiving Federal recognition, the Pamunkey announced plans for a large ($700 million) gambling facility.

The tribe did not propose to build on its reservation. Instead, it planned to partner with an investor group and acquire land somewhere within what the tribe considered its historic territory. Federal law allowed the Pamunkey to operate non-casino games such as bingo, under regulations of the National Indian Gaming Commission. When the tribe received Federal recognition, it was required to negotiate a compact with the state before opening a Las Vegas-like casino with slot machines, blackjack, and roulette.23

Spurred by the potential of having just one casino-style business in Virginia, the General Assembly then passed legislation authorizing full casino gambling in six cities. The Pamunkey ended up with the rights to build a casino in Norfolk. They competed for the license in Richmond, highlighting their unique character, but were not successful in obtaining that license.

Federal recognition allowed the tribes to receive direct funding. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021, the six tribes recognized by the US Congress in the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act declared a state of emergency and then received $19 million through the Cares Act. Without recognition, Federal funding to mitigate impacts of the pandemic would have been channeled through state agencies and the full $19 million might not have reached the tribes.24

In 2022, the seven Federally-recognized tribes received funding for affordable housing efforts from Indian Housing Block Grant Program. The state-recognized tribes which were not Federally recognized did not qualify for the funding. The Pamunkey Tribal Nation qualified for a Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program Award under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, and in 2022 was awarded a $500,000 grant to expand internet access to the 48 homes on the reservation.25

State laws continued to limit the options for officially-recognized tribes. When the Rappahannock Tribe and the Chesapeake Conservancy partnered to acquire land at Fones Cliff, they discovered that that the Bureau of Indian Affairs was not authorized under Virginia law to "hold" conservation easements for the tribe.

Federal recognition did authorize the National Park Service to sign a Tribal Historic Preservation agreement with the Rappahannock tribe in 2024. The Tappahannock created a Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) under Section 101 of the National Historic Preservation Act, fulfilling a role that previously had been served by the State Historic Preservation Office. Tribal Historic Preservation agreements had already been signed with over 200 other tribes across the United States.

The General Assembly created the Virginia Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Historic Preservation Fund in 2022, and also the Commission on Updating Virginia Law to Reflect Federal Recognition of Virginia Tribes:26

On November 7, 2024, after three years of preparation, the Mattaponi filed their petition seeking administrative recognition with the Bureau of Indian Affairs' Office of Federal Acknowledgement. The tribe hired Kenah Consulting to prepare the 2,000 pages of documentation, but tribal members conducted much of the research. The Mattaponi anticipated the Bureau of Indian Affairs would require two-three years to make a decision. The Pamunkey expressed support for recognition, as did Governor Glenn Youngkin.

The Mattaponi had delayed filing because there was not a consensus within the tribe that Federal recognition was worth the cost and effort. A $1.4 million grant in 2021 from the Administration for Native Americans, a Federal agency within the US Department of Health and Human Services, triggered action.

At the 347th Tribute Ceremony on November 26, 2024, the tribe presented a deer to Governor Youngkin based on the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation. At the ceremony one member of the tribe said:27

Chief Mark "Falling Star" Custalow honored a provision in the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation for the 347th time in 2024, by presenting a deer to Governor Youngkin

Source: Governor of Virginia, Governor Glenn Youngkin Participates in 347th Tribute Ceremony (November 26, 2024)

Rep. Jennifer McClellan filed a bill for Congressional representation of the Nottoway tribe in December, 2024. The filing occurred at the end of the 118th Congress, 2nd Session, so it was obvious that no action would occur until the 119th Congress assembled and the bill was filed again. The Congresswoman said:28

Seven Federally-recognized tribes partnered to start an annual Sovereign Nations of Virginia Conference in 2020. In 2025 the tribes, organized as the Indigenous Conservation Council of the Chesapeake Bay, asked to become official members of the Chesapeake Executive Council. That group makes decisions for the Chesapeake Bay Program. The tribes sought to establish a government-to-government relationship to improve land conservation planning, coordinate restoration efforts (including aquaculture), and provide traditional ecological knowledge.29

the fifth Sovereign Nations Conference was held in 2025

Source: Sovereign Nations of Virginia Conference

The Executive Council declined to admit the Indigenous Conservation Council as a full member and suggested instead that it serve in an advisory role. Full membership would give the group a vote in how to allocate funding from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) among the members of the Exexcutive Council. Chief Anne Richardson, head of the Indigenous Conservation Council and also the Rappahannock Tribe, said in response:30

four other tribes in Virginia are officially recognized by the state, but not by the Federal government

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federally-Recognized Tribes in EPA's Mid-Atlantic Region