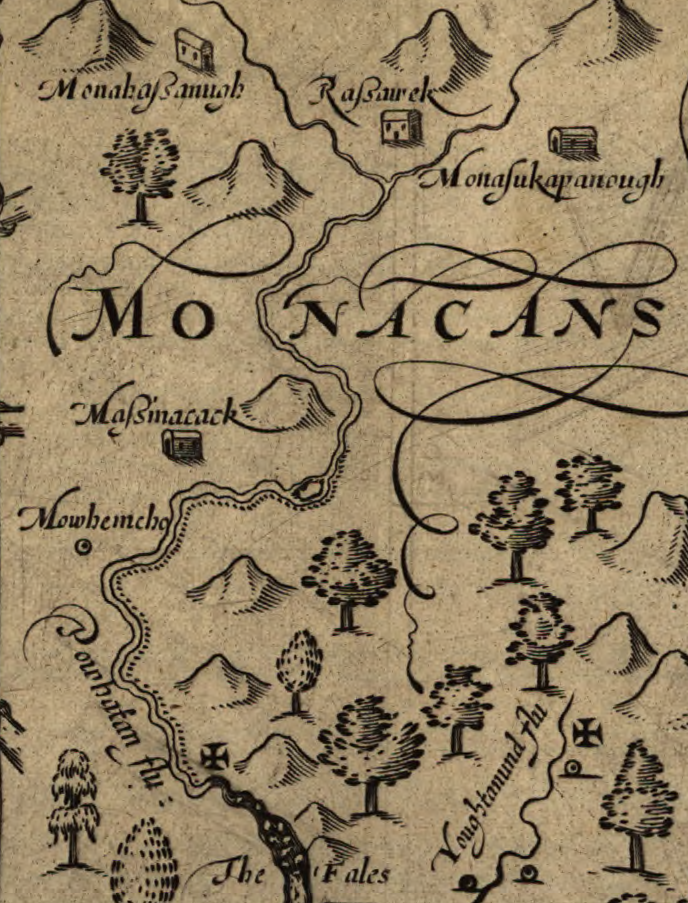

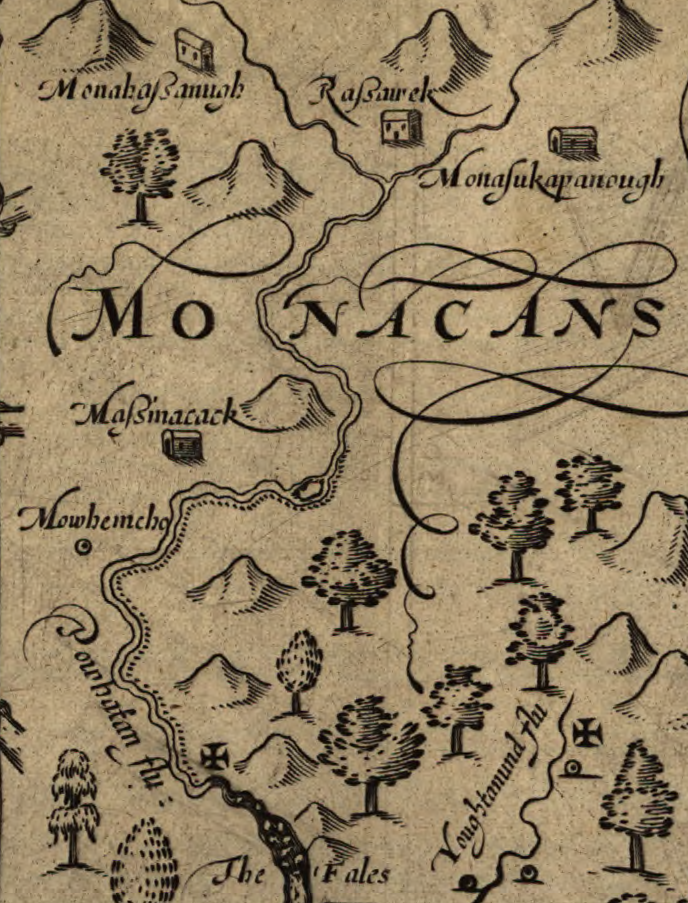

John Smith located five Monacan villages in the Piedmont upstream of the Fall Line of the James River: Monahassanugh, Rassawek, Mowhemencho, Monassukapanough, and Massinacack

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

John Smith located five Monacan villages in the Piedmont upstream of the Fall Line of the James River: Monahassanugh, Rassawek, Mowhemencho, Monassukapanough, and Massinacack

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

When the English colonists arrived in 1607, the Monacan were both traders with - and rivals of - paramount chief Powhatan.

The Monacans lived west of the Fall Line up to the headwaters of the James River, between the Manahoac to the north and the Tutelo/Saponi to the south. The tribes on the Piedmont spoke Siouan languages. Those on the Coastal Plain east of the Fall Line, controlled by Powhatan in the territory between the Rappahannock and Meherrin rivers known as Tsenacommacah, spoke Algonquian languages.

Source: Jefferson-Madison Regional Library (JMRL), Ancestral Monacan Homelands with Jeffrey Hantman

Siouan speakers may have migrated into Virginia across the Allegheny Mountains from the Ohio River valley, via the Big Sandy River or Kanawha drainages, roughly 4,000 years ago. According to a modern scholar, the name of the Monacans could be derived from the word "mani." It meant "water" in the Siouan language spoken by the Tutelo, who lived south of the Monacan territory on the Piedmont and in the Blue Ridge.

John Smith recorded the tribe's name at least five ways: Monacans, Massinnacacks, Russawmeake, Monahassanuggs, and Mouhemenchughes.

The distinction between Monacan, Tutelo, and Saponi may reflect an artificial perspective of colonists; the three groups could have been part of a common culture occupying the Piedmont from the Dan River north to the Potomac River. The Monacan call themselves "Yesan," for "the people."

The Monacan town of Monasukapanough was located at a crossing point of the Rivanna River, and the name may include the Siouan word for "ford" - "moni." Their primary town was Rassawek, at the confluence of what today we call the Rivanna and James Rivers. Those modern river names are derived from English rulers Queen Anne and King James I; we have no idea what names the Monacan used.1

the site of Monasukapanough/Monahassanugh is on the river now called Rivanna, just north of modern-day Charlottesville

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The English learned that the Monacan existed west of Tsenacommacah on May 24, 1607, while exploring up the James River until blocked by the falls at what is now Richmond. The new colonists wanted to meet with the Monacan, in hopes of discovering gold/silver comparable to what the Spanish found in Mexico and Peru. They also wanted to meet Powhatan's rivals, in hopes of gaining some leverage over the paramount chief who controlled the area around Jamestown. To monopolize trade with the English and to control the prestige goods acquired, Powhatan's people blocked the initial plans of the English to travel upriver into Monacan territory.

John Smith gained the next intelligence about the Monacans in August, 1608. He captured a Siouan-speaking Native American, Amoroleck, after traveling up the Rappahannock River to what is now Fredericksburg. Through an interpreter, Smith learned the Monacans lived in the hilly country south of Amorolek's Manahoc towns. Like the Manahoacs, the Monacans lived along rivers and relied upon hunting as well as agriculture for food.

In September 1608, Captain Christopher Newport led an expedition past the Fall Line of the James River. He intended to meet with the Monacans, despite Powhatan's objections. They may have gone as much as 40 miles upriver in two and a half days, and reached the towns of Monhemenchouch and Massinacak, 14 miles further west at the confluence of James and Mohawk Creek (called Mahock Creek by John Lederer in 1670). Today, those sites are located in the inappropriately-named Powhatan County.

The English found no gold or silver. They turned back downstream before reaching the Monacan's primary town of Rassawek at the confluence of the Rivanna and James rivers, or Monasukapanough further up the Rivanna at modern-day Charlottesville.2

in 1608 Christopher Newport may have reached the Monacan town of Massinacak, just downstream from modern Powhatan State Park

Source: North Carolina Maps, ArcGIS Online

John Smith mapped the locations of five Monacan towns, based on interviews with various Native Americans that he encountered - Mowhemcho, Massinacack, Monasukapanough, Rasswek, and Monahassanough. His Maltese cross indicates that he traveled only to the Fall Line of the James River, perhaps reaching the site of the modern Huguenot Bridge.

When John Smith arrived, the Monacan confederacy included around 10 towns:3

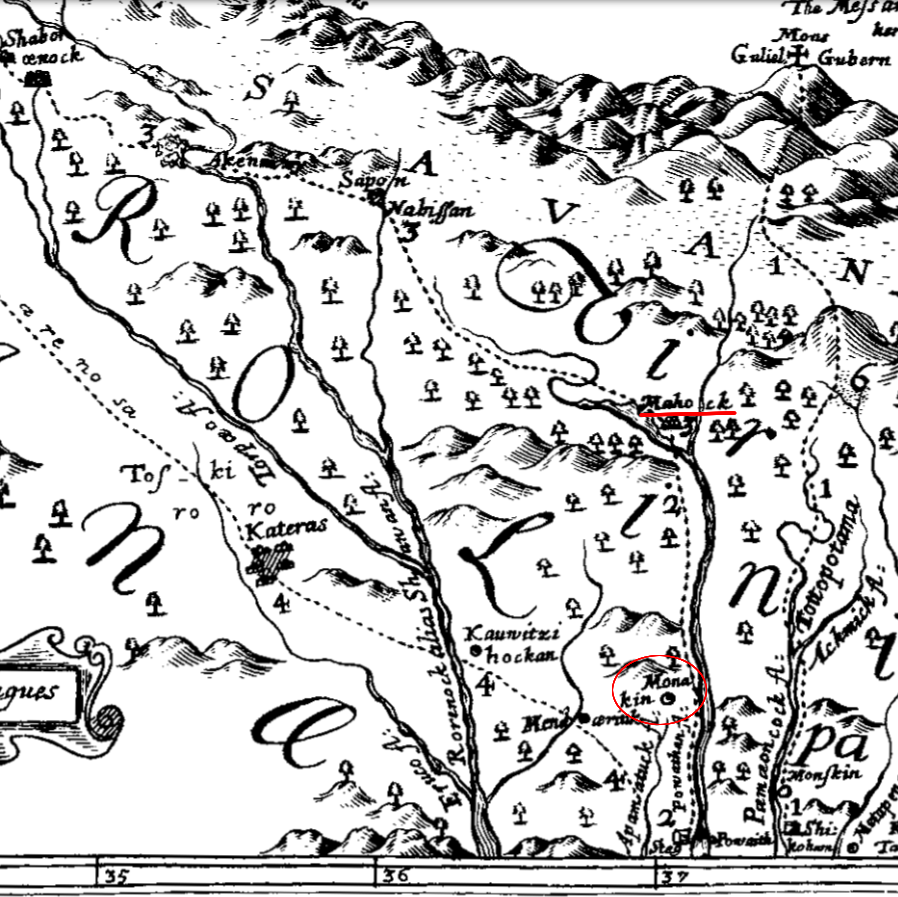

English familiarity with the Monacans remained limited throughout the 1600's. John Lederer passed through their territory on his second journey to the Blue Ridge in 1670. He recorded the continued presence of Monhemenchouch and Massinacak.

John Lederer visited the two Monacan towns closest to the Fall Line in 1670

Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Discoveries of John Lederer (1672)

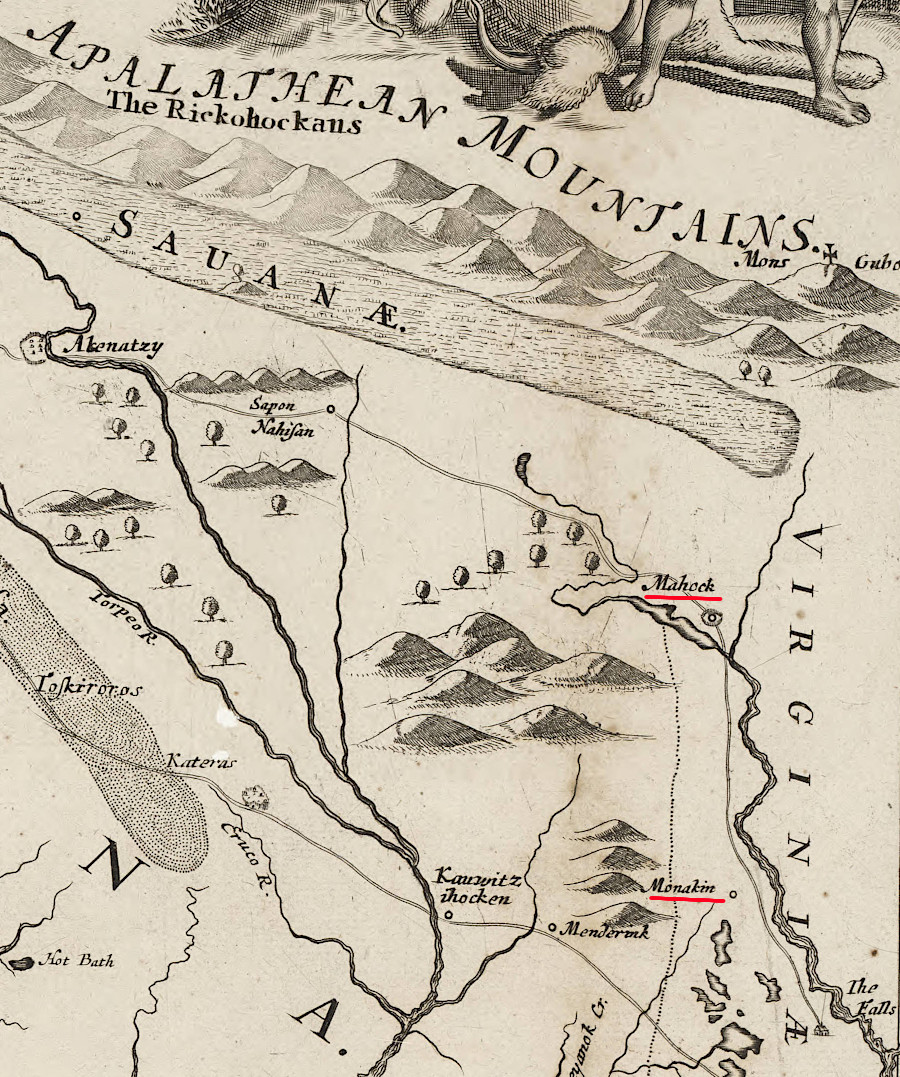

When John Ogilby sketched the possible North Carolina-Virginia border to a speculative location near the mouth of the Rivanna River in 1671, he documented only two Monacan towns which he called Monakin and Mahock. His map may have reflected just European unfamiliarity with the territory controlled by the Monacans, but the absence of other towns could also reflect population decline in the Piedmont.

a 1671 map showed only two Monacan towns

Source: North Carolina Maps, A new discription of Carolina by the order of the Lords Proprietors (John Ogilby, ~1671)

Permanent towns in the eastern part of the Monacan territory along the James River were abandoned between 1670-1690. The people moved west to live in the mountains, and south to join with the Tutelo/Saponi. The Monacans never left, but their settlement pattern was disrupted as the English pushed west of the Fall Line.

Mowhemencho was still visited regularly by the Monacans in 1702, when the site was called Manakin Town by the Huguenots who had settled there in 1699. Franz Louis Michel recorded:4

as late as the American Revolution, mapmakers still highlighted the historic Monacan presence along the James River

Source: Library of Congress, Bowles's new pocket map of the United States of America (by Carington Bowles, 1784)

Before the Monacan tribe evolved, their territory had been occupied earlier by a culture which shared a key characteristic with Native Americans in the Mississippi River Valley: burying the dead in mounds. The Monacans may have continued that practice, unlike the Algonquian-speaking tribes east of the Fall Line which the English encountered, or they may have just venerated the old mounds while burying their dead elsewhere.

In the early 1700's, Native Americans crossing the Rivanna River reportedly stopped to pay respects at the ancient burial mound at the former site of Monasukapanough. The visitors may have been Cherokee, Catawba, or members of another tribe passing through rather than Monacans still living in the local area. Thomas Jefferson excavated that mound in the 1780's as he was writing Notes on the State of Virginia. By 1911, the Rivanna River mound had been flattened by plowing, soil removal, and flooding.

The Smithsonian sponsored excavations of the site of Monasukapanough in 1911 and in 1931. The town had been located on both sides of the South Fork of the Rivanna River. In 2001, a developer proposed construction of a soccer complex on the site of the town located across the river from the mound. The Archaeological Conservancy, University of Virginia, and the Monacan Nation arranged for another archeological project that documented long occupation of the site from 1300-1670. That data was used in the Monacan Nation's successful effort in 2017 to become a Federally recognized tribe.

Absence of evidence can be as useful as the presence of artifacts. The absence of early European trade items from the Monacan sites suggests they did not interact closely with the Jamestown colonists. Trade may have been blocked by Chief Powhatan, or the Monacans may have chosen not to interact with the colonists.

The English who arrived in 1607 certaining desired to trade with groups beyond Powhatan's control; John Smith traveled up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608 to bypass him and initiate relations with groups living outside of Powhatan's Tsenacomoco. Captain Newport managed an initial trip in 1607 up the James River beyond the Fall Line, but after the start of the first Anglo-Powhatan war in 1609 the English may not have been able to reach what they ultimately named the Rivanna River. By 1650, after the Third Angl;o-Powhatan War, the Monacan towns may have been largely abandoned.5

Source: Ivy Creek Foundation, The History of the Monacan Nation and Town of Monasukapanough: An Ivy Talk

The Monacan struggled to maintain control of the Piedmont after English settlers arrived. The warring Iroquois to the north and Cherokee/Catawba to the south were more powerful; they had more guns obtained from the Europeans. Raids by other Native American tribes through Virginia in the 1600's threatened the Native American inhabitants on the Piedmont as well as the colonists on the Coastal Plain.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois) defeated rival tribes to the north and west during the Beaver Wars of the 1640's and 1650's. In the 1670's, they seized control over the Susquehannock and Nanticoke to the south in Maryland and what became Pennsylvania/Delaware. Display of fighting capacity and "mourning wars" were critical components in the Iroquois culture, and the five tribes based in New York expanded their raids further south to fight the Catawba and Cherokee.

English colonists began to occupy the area now within Albemarle County in the 1720's; the county itself was formed in 1744. By the time settlers arrived at the base of the Blue Ridge, the Monacan towns along major rivers had been abandoned. The Siouan-speaking tribes on the Piedmont of Virginia such as the Monacan, Tutelo and Saponi had been disrupted and displaced by other Native Americans before colonial settlers arrived in large numbers.

Many of the Monacans joined with the Tutelo, Saponi, and other Siouan-speaking tribes, but they never completely left the James River watershed. The people retreated into the Blue Ridge to avoid conflict with rival Native Americans and later the settlers.7

Though the Monacan towns on the floodplains along the Rivanna and James rivers were no longer occupied, Monacans continued to live in the ridges and valleys of what became Albemarle, Nelson, and Amherst counties. They survived on the fringe of "American" society, intermarrying with enslaved people who escaped as well as white settlers. An archeologist who excavated the Rivanna (Jefferson) Mound in 1911 reported:6

The territory controlled by the Monacan when colonists arrived include two burial mounds built originally during the Mississippian culture time period. Construction of the Rivanna (Jefferson) Mound in the headwaters of the Rivanna River and the Rapidan Mound in the headwaters of the Rapidan River started before 1400CE (Common Era). The Monacans and/or the Manahoacs may have continued to use those burial mounds as ceremonial sites, spiritual places, or even for their own burials. Removal of the top portions makes it impossible to date their last use.

The Monacans as an organized polity may have developed after earlier occupation of the area by people who brought/adopted the Moundbuilder culture, but are presumed to have continued the burial traditions:7

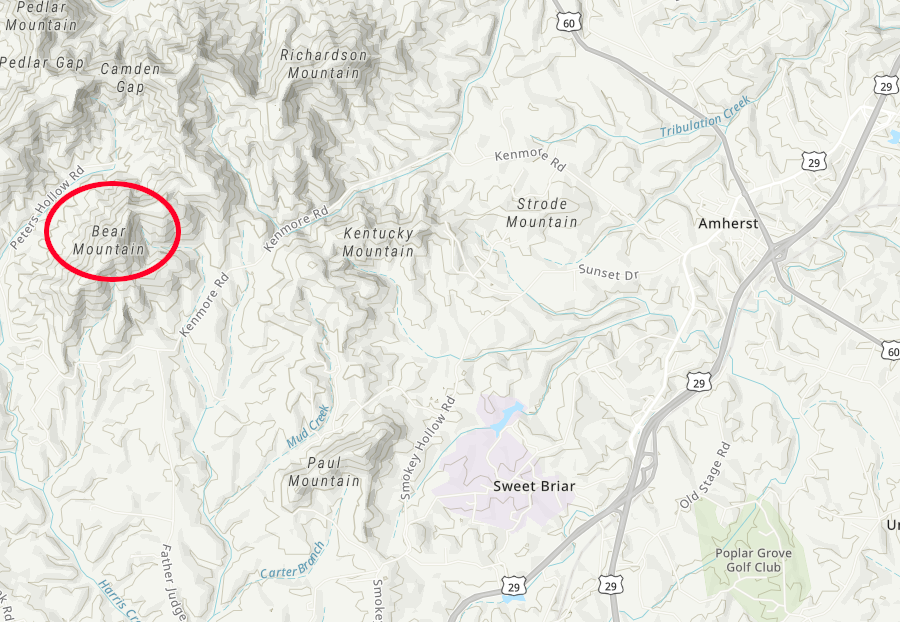

The population of the Monacan/Tutelo/Saponi/Occaneechi and other closely-related tribes may have totaled 10,000-20,000 people before European contact. At the start of the 21st Century, Monacan Chief Kenneth Branham estimated that the Monacan population had dropped to around 500 people in the middle of the 1700's. Most lived in the mountains in Amherst County, especially Bear Mountain.8

In 1908, the Episcopal denomination started Saint Paul's Mission and the Bear Mountain Indian Mission School. Those facilities became the focal point of their community, and today the public is less aware of the older Buffalo Ridge community in Nelson County.

The Bear Mountain church was destroyed by fire in 1930, but quickly rebuilt. The school was segregated so only Monacans attended. The Monacans were educated through the seventh grade in that one school until public schools were integrated in 1963.

The tribe is officially the Monacan Indian Nation, Inc., incorporated in 1988 as a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization. The state granted official recognition to the tribe on February 14, 1989.

The Episcopal Church donated their claims to the mission property back to the Monacans in 1995, retaining ownership of just the church building and a structure for the caretakers. The tribe has restored the log cabin, built around 1868 and used as a church, so it is now a tribal museum.

Today there are about 2,100 members, with around 500 living in Amherst County.

The 12 members on the Tribal Council are elected for four-year terms. Membership in the tribe, including the right to vote in elections, is based on descent from someone listed on the "original rolls" that were compiled from genealogical data and oral histories in the 1980's and 1990's.9

Federal government recognition occurred on January 29, 2018, when President Trump signed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. The tribe chose to get Federal recognition through a law passed by the US Congress, rather than through the administrative procedures followed by the Pamunkey. Records documenting the continued existence of the Monacans since the 1600's were sparse, in part because the Commonwealth of Virginia had sought after 1924 to declare that there were no Native Americans in Virginia and everyone must be classified as "white" or "colored."

One impact of choosing the legislative route to recognition is that the Monacans are not eligible to operate any gambling facilities on their land, even if it were to be taken into trust by the US Department of the Interior. The land owned by the Monacan Indian Nation, Inc. is private property. It is not held in trust by the Federal government like Native American reservations in western states. It is not held in trust by the Commonwealth of Virginia either, as are the reservations of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi.10

Preservation of Monacan heritage is still an ongoing issue. The site of Rassawek, at the mouth of the Rivanna River, was damaged by construction of a natural gas pipeline in the 1980's. Remnants could have been altered by plans of the James River Water Authority (JRWA) to build a water pump station there, at "Point of Fork" next to the former town of Columbia. The growth plans were based upon transporting water from the James River for Louisa and Fluvanna counties to develop Zion Crossroads.

After a public uproar, in 2022 the James River Water Authority officially decided to move the site of the proposed pump station to another location two miles upriver. The cost for the modified project was projected to be $35-40 million, compared to the original $23 million estimate.11

The tribe opened a new business office in 2021 in Amherst County, north of Lynchburg. The new building offered a major improvement over the former location on South Main Street in the town of Amherst; it was connected to high-speed internet. The $10 million complex on six acres included a senior center as well as offices for tribal employees.

Since the Monacan were a Federally-recognized tribe, the new headquarters also included an Indian Health Service clinic. At the groundbreaking ceremony, a tribal official noted it was the first such clinic in Virginia (a second was planned in Richmond), and would provide free health care to members of any Federally recognized Native American tribe.12

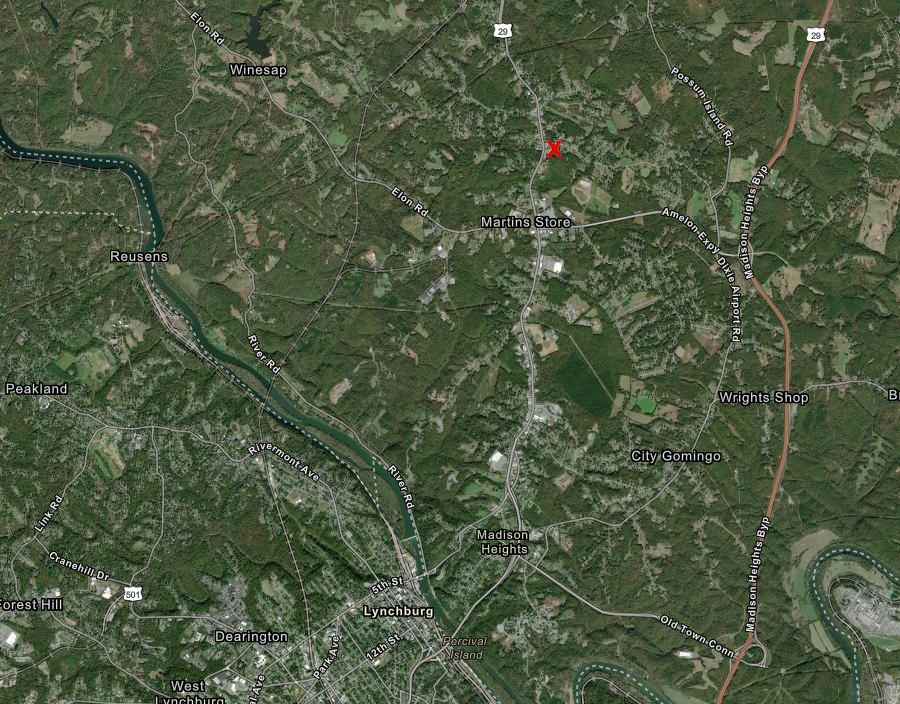

the Monacan Highview Complex is located near Monroe in Amherst County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

today the Monacan community is centered on Bear Mountain, west of Amherst

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the log cabin schoolhouse and chapel at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Amherst Indian School and Mission: Falling Rock (by Jackson Davis, 1915)

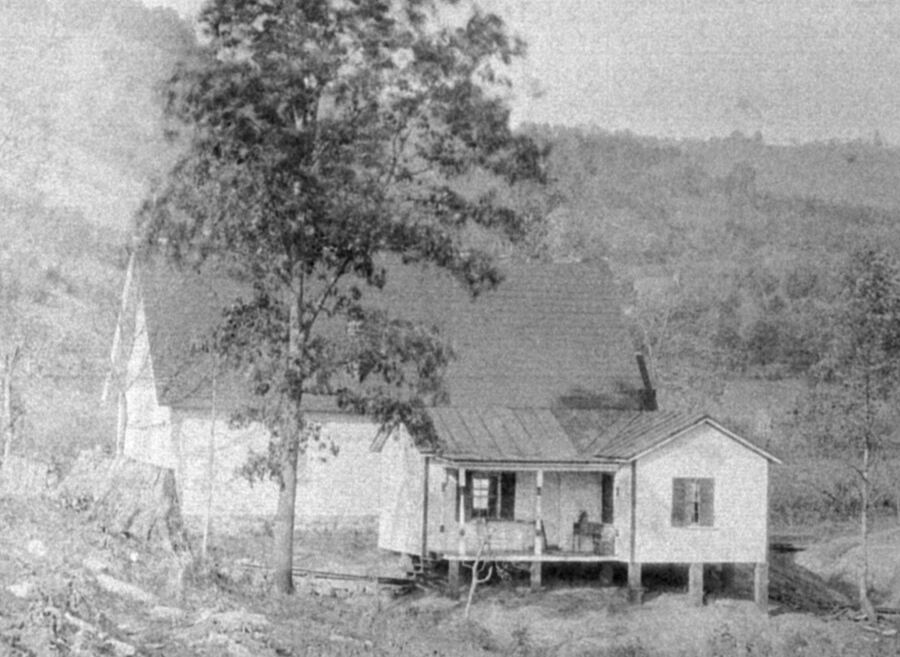

teacher's cabin at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Amherst Indian School Chapel and Teachers Cottage (by Jackson Davis, 1914)

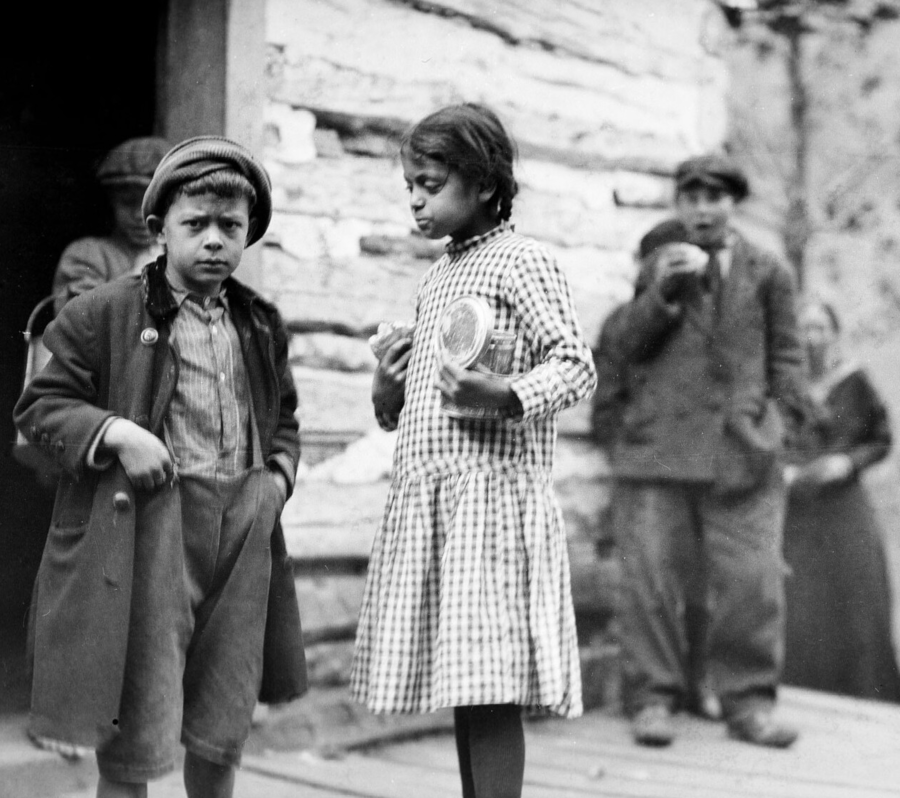

students at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Amherst: Group of Students. Indian Mission School (by Jackson Davis, 1914)

inside the schoolhouse at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Group of Students Indian Mission School, Falling Rock (by Jackson Davis, between 1914-1947)

inside the schoolhouse at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Indian Mission School, Falling Rock (by Jackson Davis, between 1914-1947)

students at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Group of students Indian Mission, Falling Rock (by Jackson Davis, 1914)

students at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Group of Students Indian Mission, Falling Rock, Recess Time (by Jackson Davis, 1914)

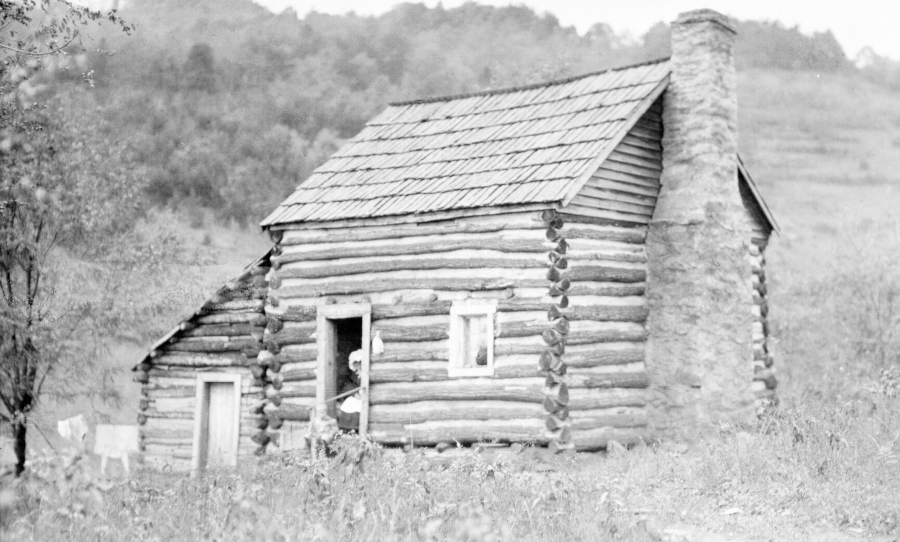

log cabin home at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Amherst Indian Settlement, Falling Rock. Log Cabin (by Jackson Davis, between 1914-1947)

grandmother in cabin at Bear Mountain

Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Old Woman in Door of Log Cabin. Indian Settlement. Grandmother of 48 (by Jackson Davis, between 1915-1947)

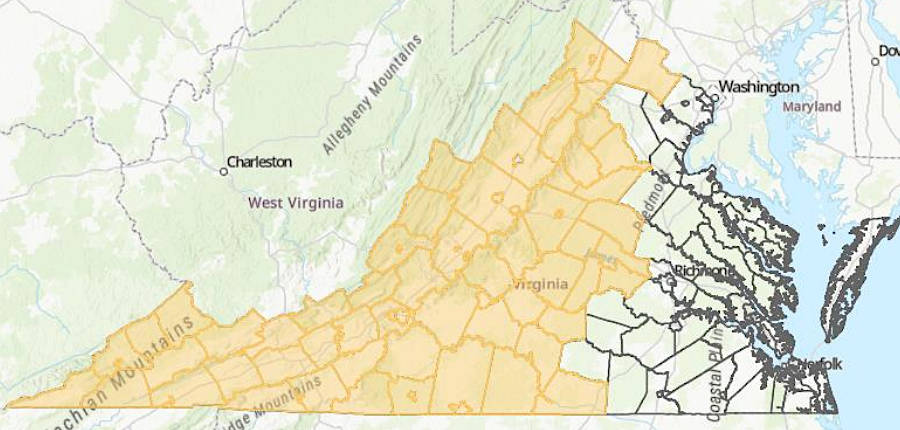

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Monacan tribe should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation