Cedar Island is a barrier island on the Atlantic Ocean side of Accomack County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Cedar Island is a barrier island on the Atlantic Ocean side of Accomack County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

On the Chesapeake Bay side of Accomack County, Saxis and Tangier islands are two barrier islands that have been developed. On the Eastern Shore, most barrier islands have been left in their natural state rather than developed into vacation resorts. Two exceptions, Chincoteague and Wallops islands, have been developed. Those two are fetch-limited barrier islands, where modern development is protected from direct Atlantic Ocean wave action.

On Hog Island, the community of Broadwater was abandoned in the 1930's after shoreline erosion and storms caused extensive flooding. Many of the structures in Broadwater were floated over to Willis Wharf on the mainland, where they became part of the "Little Hog Island" community. As described by the Accomack-Northampton Planning District Commission:1

Efforts to develop the third, Cedar Island, have demonstrated the folly of building houses on exposed barrier islands - and the challenge to traditional concepts of real estate ownership, when the property consists of sand that moves. Cedar Island today is a seven-mile island with a thin sand layer less than three feet thick, where endangered piping plovers nest.

The sand is exposed on the Atlantic Ocean side of the island, with a marsh to the west. The sand layer is constantly moving westward, washed by waves up and over the back-barrier marsh.

the eastern edge of Cedar Island is a thin wedge of sand, with a backbarrier marsh to the west

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Twice, developers planned to sell thousands of lots and build houses on Cedar Island. In the 1950's, Richard Hall proposed developing "Ocean City." He platted 2,000 lots, and proposed a bridge connecting the island to the Eastern Shore mainland. He expected to generate private profits from the new publicly-funded access to the Eastern Shore, after the US 50 highway was extended east by a new bridge across the Chesapeake Bay from Annapolis.

Hall advertised in his 1951 sales brochure:2

In the 1980's, Hall's granddaughter Elizabeth and her husband, Ben Benson, tried once again to market the island as a site for vacation homes. They owned roughly 95% of the 2,100 acres of the island. They took 100 of the original 2,200 lots, then realigned boundaries to create 69 lots which extended 3,000 feet further to the west. The speculative real estate project included a plan to donate 1,244 acres of undevelopable marsh to the Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

Without any commitment by the Commonwealth of Virginia to build a bridge to the island, the Benson's sold $3 million worth of lots to customers by emphasizing privacy. Some purchasers paid $100,000 for their lot. Marketing highlighted the rare opportunity to live directly on the waterfront of one of the last unspoiled Atlantic islands. The sales brochure said:3

Cedar Island, south of Metompkin Island, is occasionally broken into two parts by an inlet

Source: US Geological Survey, Metompkin Inlet 1:24,000 topographic Map

Accomack County opposed the authorization of new houses, but it had failed to assume local responsibility to administer the state's Coastal Primary Sand Dune Act. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission had the authority to protect the primary dune line, undrr Virginia's Barrier Island Policy. Nonetheless, the state officials chose to authorize the development of 69 new residences.

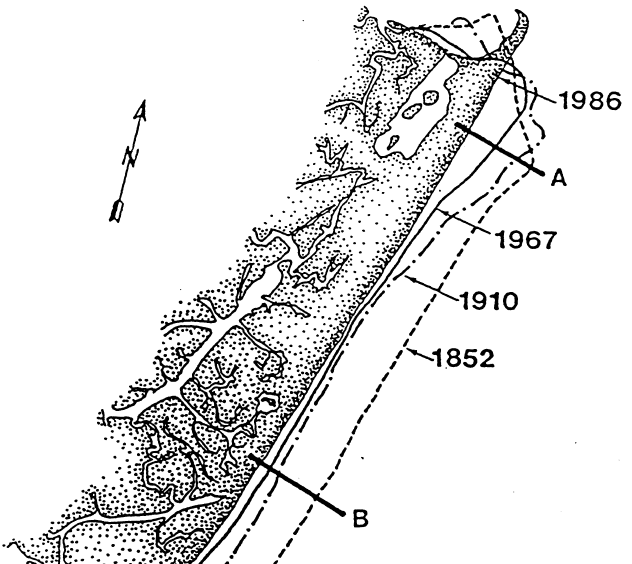

The geological instability of the island was well known. In 1987, a state report noted the erosion rate was 18-21 feet per year, and 90% of the island was inundated at least once every ten years.

Accomack County officials feared that after new houses were built on the barrier island, there would be demands for the county to provide expensive services. In a storm, search and rescue might be called. If erosion threatened the new structures, the county might be asked to fund protective barriers.

Mrs. Benson responded:4

There was the potential for a line of houses on Cedar Island, even on stilts, to block the recycling of sand. Instead of washing over into the marsh, the structures could redirect the sand to offshore shoals. Without retention of the sand on the island slightly further to the west, the entire above-water portion could disappear. In 1986, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) had determined:5

shoreline retreat at Cedar Island, 1852-1986

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Assessment Of The Development Of Cedar Island, Virginia (Appendix B)

In 1990 the Virginia Marine Resources Commission revised its regulations allowing new homes to be constructed on barrier islands and adopted a formula to determine how far back new structures had to be located from receding shorelines. Staff had recommended requiring new structures to be located far from the shoreline, at least 50 times the recession rate averaged over the last century. Based on that recommendation, "average" erosion would not threaten the house for the next 50 years.6

Instead, the state agency established a policy allowing construction closer to the water:7

Cedar Island, morphing over time

Source: Google Earth Engine

The difference between the 50-year line and the 20-year line made construction of new waterfront cottages far more attractive, offering a closer view of the waves:8

By 1997, property owners had constructed 27 houses on the sand along the east side of Cedar Island, where they had spectacular views facing the ocean. Within two decades, only two homes and the former Coast Guard station remained on the island. Other structure fell victim to the rapid migration of the sand. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission tried to force former homeowners to remove the pilings that once supported structures but were now on submerged land, because they created a risk to navigation.

Some homeowners just abandoned their houses, ignoring the requirement of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to remove the structure before it collapsed. As an article in the Baltimore Sun noted:9

structures on Cedar Island on May 8, 2004

structures on Cedar Island on October 28, 2004

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality,

Human Impacts To Sensitive Natural Resources

on the Atlantic Barrier Islands on the Eastern Shore of Virginia - 2005 Report

Land ownership on the island today is confusing. The US Fish and Wildlife Service and The Nature Conservancy have purchased parcels. Some lot owners donated their parcels to obtain tax writeoffs, while others remain in private ownership. The Cedar Island Division of Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge contains over 1,400 acres in fee title and 600 acres in easements, including 1,200 acres donated in fee and another 600 acres of easements donated by the Bensons in 1986.10

submerged lots offshore from Cedar Island - taxed by Accomack County, but who really owns them?

Source: AccoMap - Accomack County's Online Mapping Service

The biggest legal challenge today involves dealing with submerged lots. Real estate law recognizes that shorelines change naturally. If change is gradual, then submerged areas can accumulate sediments and become upland. To ensure waterfront property owners retain access to the water, "accreted" land is simply added to the ownership of adjacent property. However, if the shift in a shoreline is sudden, typically through a storm or "avulsion," then property lines may remain fixed and the old shoreline property owner may discover that someone else owns the new land, blocking access to the water.

On Cedar Island, entire lots that were once waterfront property are now completely submerged. Old subdivision property lines are still used by Accomack County to bill for property taxes, even if the current lot is underwater. Legally, it is unclear if the old lot is still privately owned, or if the Commonwealth of Virginia acquired title once the entire lot became submerged land below the low-water mark.

assessed values of submerged lots offshore from Cedar Island are appraised as worth $100 by Accomack County, while lots with actual land could be worth over $17,000

Source: AccoMap - Accomack County's Online Mapping Service

Taking advantage of the confusion, an attorney purchased lots on Cedar Island. He then claimed that a 140-acre sandbar had "rolled back" on top of the lot boundaries, so it was his private property. The sandbar was not suitable for a new dwelling, but did have value as a popular recreational stop-off for boaters. The Commonwealth of Virginia contended that the sandbar was state property, separate from Cedar Island until recent sand migration.

Until private property land claims are acquired by the state, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, or The Nature Conservancy, it will not be the last time the confusion over ownership leads to a lawsuit.11

at north end of Cedar Island, Metompkin Inlet separates Cedar Island from Metom[p]kin Island; on south end, Wachapreague Inlet separates cedar Island from Parramore Island

Source: US Geological Survey, Accomac 15X15 quadrangle map (1935)

In the last 50-100 years, the rate of sea level rise has tripled to about 4.5 millimeters per year on Virginia's coastline. That rate is faster than the global average, in part because the eastern edge of Virginia is subsiding as sea level is rising.

Over the last century, faster sea level rise has resulted in the removal of the sand and mud east of the barrier islands. There are few sediments in the Atlantic Ocean left to wash up and reconstitute Cedar Island, so it disintegrates as well as migrates. The speed of westward movement is predicted to increase 50% by the year 2100.12

Storms have created ephemeral inlets, and water surging through them has eroded away large segments of the backbarrier marsh:13

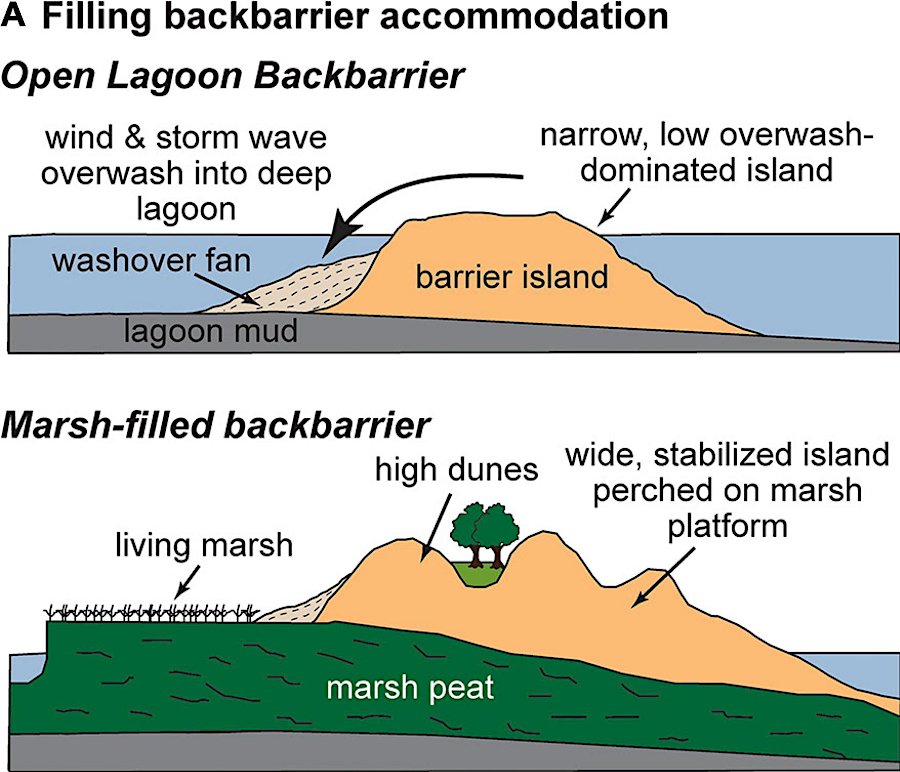

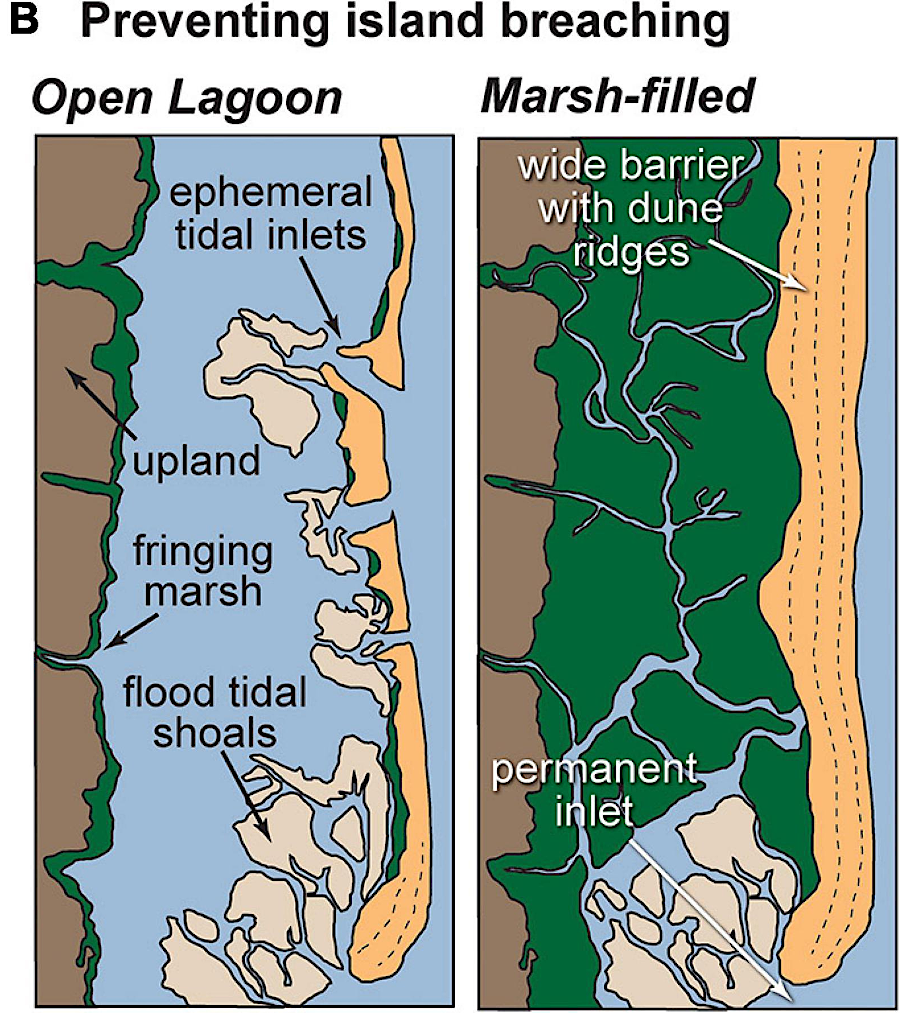

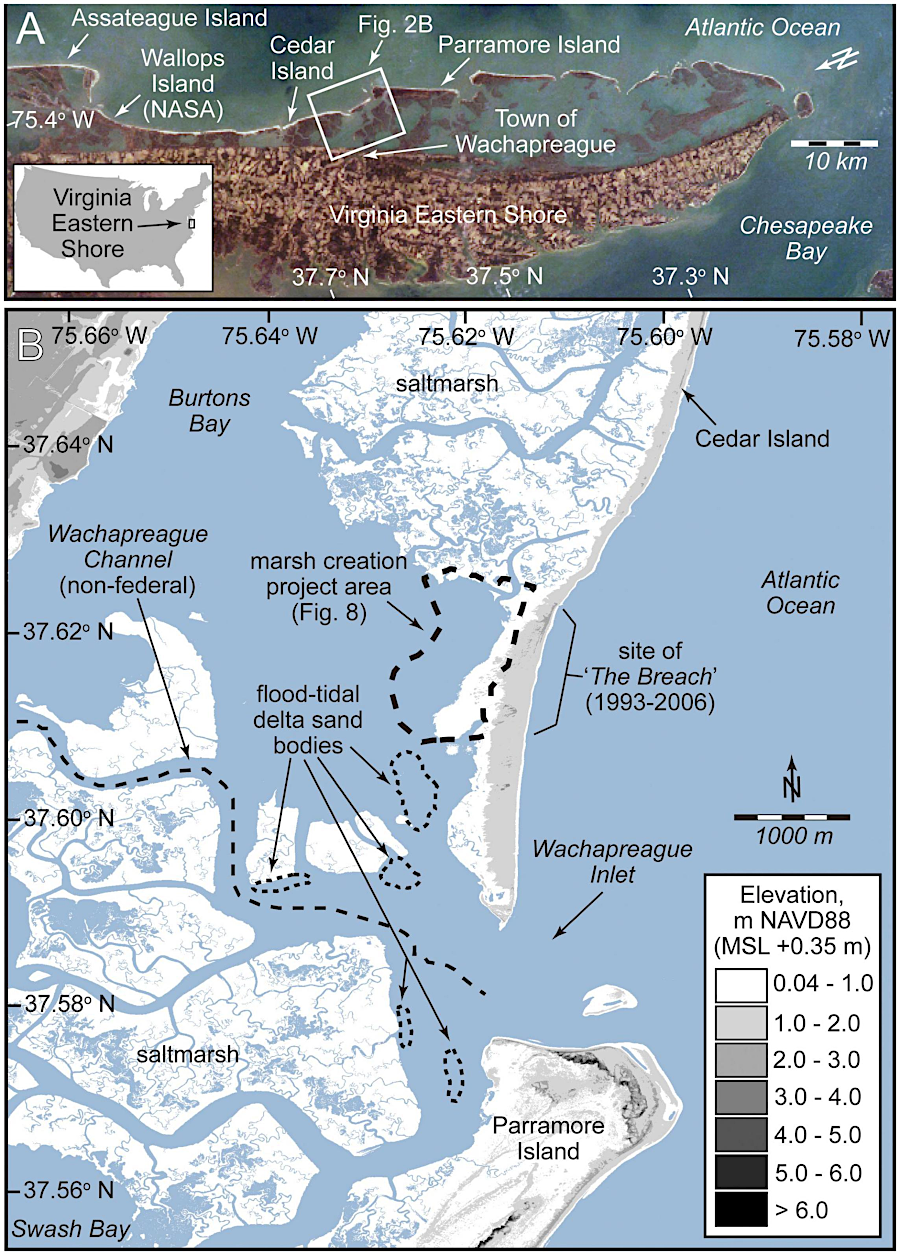

Cedar Island was moving westward as much as 45 feet per year in 2022, but it could be stabilized. Researchers have proposed creating a 216-acre marsh at the back of the southern end that would be a platform for protecting the island. The proposal involved using dredged sediments from local waterways, placing them on the western edge of Cedar Island to expand the marsh on the southern end of the island. The Eastern Shore Regional Navigational Waterways Committee supported the proposal, since it would put the dredged sediments to beneficial use and help protect the Town of Wachapreague from storms.

migration and disintegration of Cedar Island, 1985–2018

Source: Frontiers in Marine Science, Leveraging the Interdependencies Between Barrier Islands and Backbarrier Saltmarshes to Enhance Resilience to Sea-Level Rise (Figure 3)

Washover of sediments would continue, but those sediments would be deposited in the backbarrier marsh. Currently, washover sediments end up in the lagoon between the western edge of Cedar Island and the eastern edge of the mainland, and currents carry them away.

Cedar Island might be stabilized by capturing washover sdiments in a backbarrier marsh

Source: Frontiers in Marine Science, Leveraging the Interdependencies Between Barrier Islands and Backbarrier Saltmarshes to Enhance Resilience to Sea-Level Rise

Filling the lagoon west of Cedar Island with a fringing marsh platform would reduce the creation of ephemeral inlets and their erosion of the sediments which compose the island. Capturing the sediments would increase nutrients and provide new space for plant roots.14

Cedar Island might be stabilized by capturing washover sediments in a backbarrier marsh

Source: Frontiers in Marine Science, Leveraging the Interdependencies Between Barrier Islands and Backbarrier Saltmarshes to Enhance Resilience to Sea-Level Rise (Figure 1)

the new marsh would be constructed on the southern edge of Cedar Island

Source: Frontiers in Marine Science, Leveraging the Interdependencies Between Barrier Islands and Backbarrier Saltmarshes to Enhance Resilience to Sea-Level Rise (Figure 2)

land ownership (fee and easement) of US Fish and Wildlife Service on Cedar Island

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge - Cedar Island Division