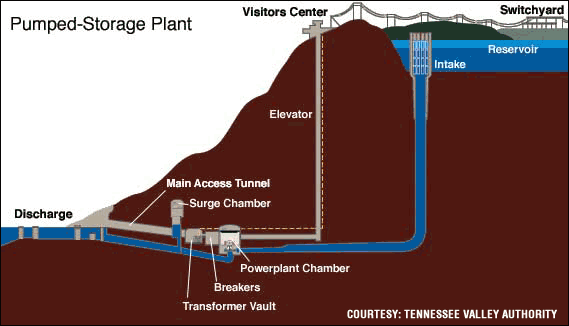

pumped storage projects consume more electricity than they generate by recycling water to provide "peak" power

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Diagram of a Pumped Storage Project

pumped storage projects consume more electricity than they generate by recycling water to provide "peak" power

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Diagram of a Pumped Storage Project

Virginia has two "pumped storage" projects generating electricity. A proposal for a third one was endorsed by the General Assembly in 2017.

Plans for another pumped storage project in Grayson County were killed by the US Congress when it designated the New River as a Wild and Scenic River in 1976. Appalachian Power's Blue Ridge project would have flooded 10% of Grayson County and created two lakes, one 30% larger than Smith Mountain Lake and a smaller one 300% larger than Claytor Lake. The proposal was supported by Virginia's governor and two US Senators, but opposed by North Carolina officials. North Carolina had greater political influence at the time.

Appalachian Power built its Smith Mountain Lake facility in the early 1960's. Two decades later, the Virginia Electric and Power Company (now Dominion Energy) built the Bath County Pumped Storage Station. It is the largest pumped storage project in the world. Between 2017-2024, Dominion Energy also was planning another pumped storage project in Tazewell County at East River Mountain.1

Utilities know they are unlikely to get public approval and government permits now to build another dam across a major river for a new hydropower facility, but do see potential to create another pumped storage facility in Virginia.

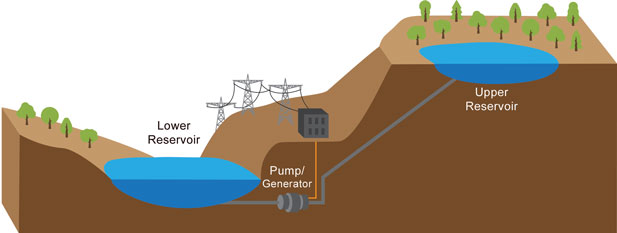

Pumped storage projects are hydropower operations. They rely upon a pair of reservoirs at different elevations. Water from the upper reservoir flows down through turbines that produce electricity, just as in any hydropower plant.

What is different from standard hydropower projects is that some or all of the water is captured in the lower reservoir, rather than allowed to run downstream. When demand for electricity is low, typically at night, water from the lower reservoir is pumped back upstream to the upper reservoir. That restocks the reservoir, and allows the same water to spin the turbines the next day when demand for electricity peaks again.

The capacity of a small stream to create electricity, such as Little Back Creek and Back Creek in Bath County, is magnified by stockpiling and recycling water between the reservoirs.

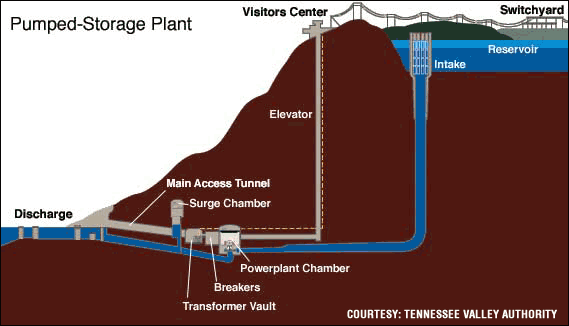

pumped storage power plants can generate electricity when demand peaks in the afternoon, then use excess baseload power from coal-fired or nuclear plants to "recharge the battery" at night

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Hourly Electricity Demand in the PJM Interconnection (July 13-19, 2013)

Most hydropower facilities generate a surplus of electricity, but pumped storage projects consume more electricity than they generate by pumping water uphill water to provide "peak" power. They are valuable to utilities because they serve as massive batteries, able to provide power quickly and inexpensive to shut down when power is not required.

At the moment, excess baseload power is available only at night. Coal-fired and nuclear power plants, supplying baseload power, produce the excess. Pumped storage facilities produce hydropower, but the original source of the energy to pump the water uphill was not "renewable." If Virginia built enough solar facilities to generate a surplus of electricity in the early afternoon, then renewable energy could be stockpiled for later use by pumping water uphill.

the Bath Pumped Storage Project consumes more electricity than it generates, and annual reports include a minus symbol for net generation

Source: US Department of Energy, Electricity Data Browser

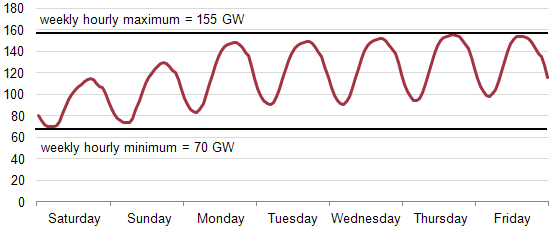

The first pumped storage project in Virginia was constructed after World War II. It was constructed where the Roanoke River cuts through Smith Mountain Gap, a site that had been considered for a hydropower dam since 1924. The pumped storage project, with an upper reservoir created by Smith Mountain Dam and a lower reservoir created by Leesville Dam, provided generation flexibility for Appalachian Power.

water from Smith Mountain Lake flows through turbines to Leesville Lake, then is pumped back into Smith Mountain Lake and used to generate hydropower again

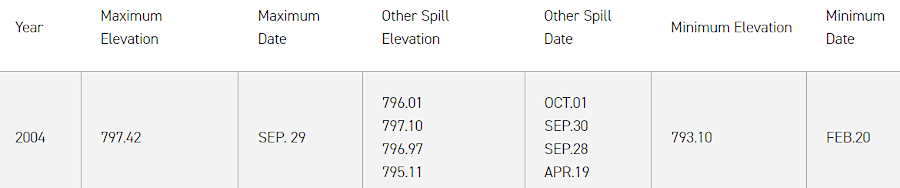

Source: Smith Mountain Project, Why the Lale Levels Change

Smith Mountain Lake reached its full size ("full pool") in 1966. At full pool, the lake is 795 feet above sea level; above that level, water can flow over the spillway. Leesville Lake at full pool is 600 feet above sea level. When hydropower is generated, Smith Mountain Lake can drop two feet in elevation to 793 feet. The water flowing through the turbines will raise smaller Leesville Lake by 13 feet, up to 613 feet above sea level, before water begins flowing over the dam.2

Smith Mountain Lake is designed to fluctuate two feet, between 795 feet and 793 feet in elevation

Source: American Electric Power, Smith Mountain Lake

The utility relied upon coal-fired power plants, baseload facilities that operated constantly. There was insufficient demand for all the electricity that could be generated during the weekends, but it was not efficient for power plant operators to cool and reheat coal-based boilers for short periods of time.

Appalachian Power determined that its excess electricity could be economically used by stockpiling water in Leesville Reservoir during the week, then pump it back up to Smith Mountain Lake on weekends. That water could then be reused, flowing through the Smith Mountain Dam turbines when demand increased again on Mondays.

It was cost-effective to build a pumped storage facility that generated power for only a portion of the week to meet peak demand, compared to building another baseload plant whose output would not be needed during the low-demand weekends. Today, the Smith Mountain Lake project has a quicker response cycle:3

As population and the economy grew in the 1960's, other utilities saw a similar need for flexibility in meeting peak demand. In the 1970's, four pumped storage projects were proposed in Virginia. Three were authorized by the Federal Power Commission, and one was built.

The Virginia Electric and Power Company (now Dominion Energy) obtained a preliminary permit in 1971 for a project using Goose Creek and Bottom Creek, tributaries to the South Fork of the Roanoke River. That permit expired in 1975.

In 1976, the Southside Electric Cooperative of Crewe obtained a preliminary permit for the Randolph Project, a series of five hydroelectric projects on the Roanoke River upstream of Kerr Reservoir that together would generate 4,090MW. A lake was planned downstream from each dam, capturing water that could be pumped back above each dam to generate electricity again.

The small utility did not follow-through with the expensive required studies, so the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission permit was cancelled in 1978.

In 1977, Appalachian Power proposed a 3,000MW pumped storage project in Scott and Wise counties. The upper reservoir would have been constructed on the South Fork of the Powell River, with a lower reservoir on Stony Creek. It withdrew its application in 1979, in part because lands in the area could be eligible for designation as wilderness.4

Construction of the Bath County Pumped Storage Station started in 1977, but was suspended in 1980 after the Virginia Electric and Power Company recalculated its peak power demands. When Appalachian Power was unable to get approvals to build its planned pumped storage project in Canaan Valley, West Virginia, the two utilities negotiated a deal. Appalachian Power purchased 40% of the Bath County project, and obtained a share of the hydropower from that site. The Bath County Pumped Storage Station was completed and went into operation in 1985.5

Unlike coal-fired and nuclear power plants, hydropower plants can generate and dispatch electricity with no "warm-up" time. Pumped storage plants recycle the water that flows through the turbines, trapping it in a lower lake and pumping it back upstream for reuse.

The elevation change between lakes normally ranges between 100-2,500 feet. Projects with less than 300 feet of elevation difference are designed for multiple purposes, especially flood control.6

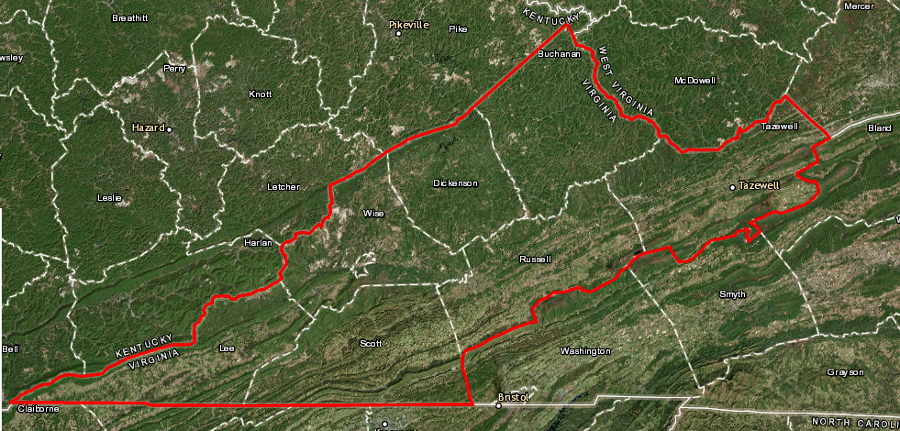

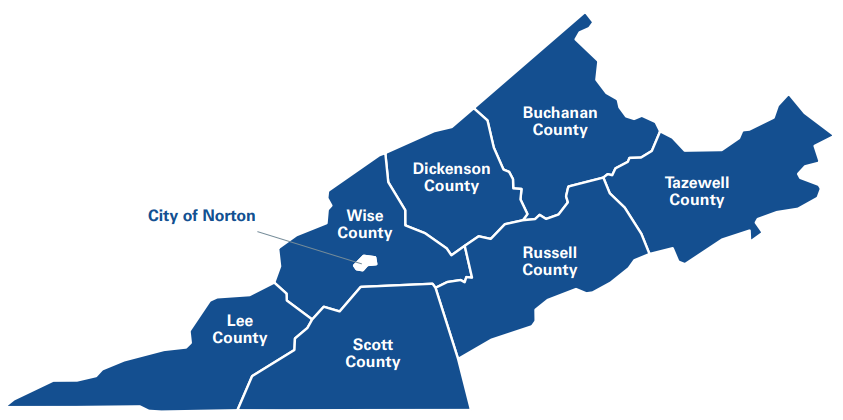

In 2017, the General Assembly modified Section 56-585.1 of the Code of Virginia. It declared that it was in the public interest to build a pumped storage project within the boundaries of the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority - Lee, Wise, Scott, Buchanan, Russell, Tazewell and Dickenson Counties plus the City of Norton).

in 2017, the General Assembly authorized a new pumped storage facility within the boundaries of the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

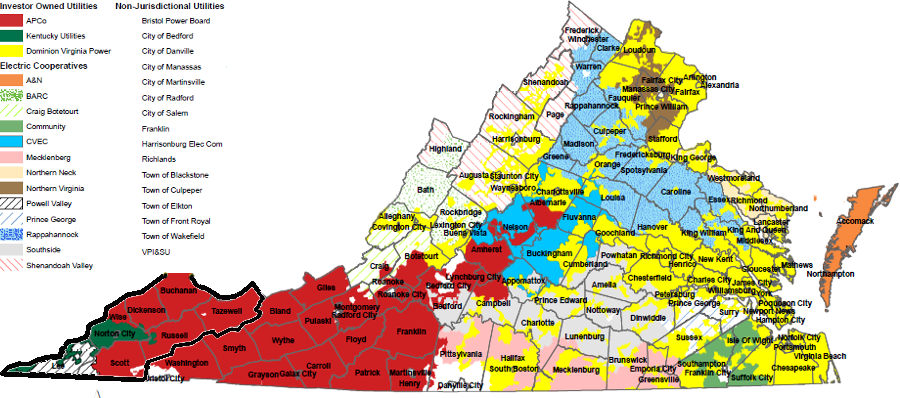

Only five utilities are authorized to provide electricity within the seven counties and one city included in the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority, but the state legislature authorized any utility to build such a project. Dominion Energy quickly expressed its interest publicly, even though the location was far outside the company's authorized service territory.7

in 2017 Dominion Energy proposed building a pumped storage project with the boundaries of the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority - far outside of its service area

Source: Virginia State Corporation Commission, Electric Service Territories

The new law pre-empted the responsibility of the State Corporation Commission to evaluate alternatives before approving such a project. That would help Appalachian Power or Dominion Energy get authorization for a pumped storage project, even if a power plant fueled by natural gas would be more cost-effective. The direction from the General Assembly was an example of how the legislature had reduced the role of the State Corporation Commission since the mid-1990's and increased the role of politics in setting energy policy within Virginia.

Southwest Virginia officials had previously managed to get the General Assembly to endorse construction of Virginia Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County, which burned waste coal and biomass to generate electricity. The cost-per-megawatt of the Virginia Hybrid Energy Center ended up substantially higher than later facilities that were fueled by natural gas.

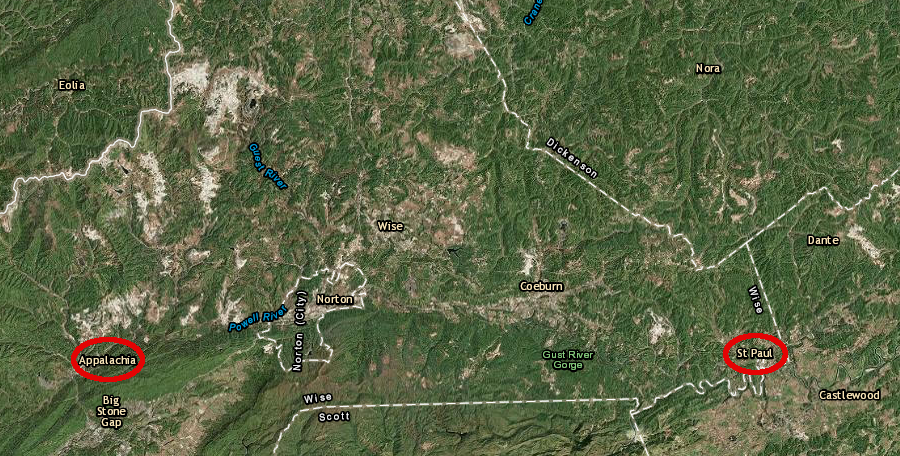

Wise County has the Virginia Hybrid Energy Center at St. Paul, and one proposed location for a pumped storage project is near Appalachia on the west side of the county

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Despite that experience, in 2017 the legislature again cleared the way for a utility to build a pumped storage project in Southwest Virginia even if that technology or location was not the most cost-effective approach.

Three legislators proposed the project, not a utility company that had identified a need for another project in the region, to generate jobs just like the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center. An influential blogger associated with Dominion Energy described the political direction to construct the Hybrid Energy Center and a pumped storage project as:8

the Coalfield Region included seven counties and one city (Norton)

Source: Dominion Energy, Powering Southwest Virginia - The Coalfield Region

The action by the General Assembly gave a green light for the utility to invest in an economically-depressed region, but there were still major hurdles for constructing an actual project. No pumped storage project in the United States has utilized coal mines as one of the storage reservoirs for a pumped storage project; sulfur within remaining coal could cause the water to become acid enough to damage the metal of the turbines. The spinning equipment has very narrow tolerances, so the threat of corrosion would require expensive water treatment and preventive maintenance.

Construction would create hundreds of jobs, but those would exist only for a brief period and could be filled by construction workers who migrate to the project from outside Southwest Virginia. A pumped storage facility would create 10-15 high-paying, permanent jobs. The utility would pay an estimated $12 million annually in property taxes. The coalfield counties and City of Norton agreed that they would share that revenue; the jurisdiction in which the pumped storage plant was located would not get all the benefits.9

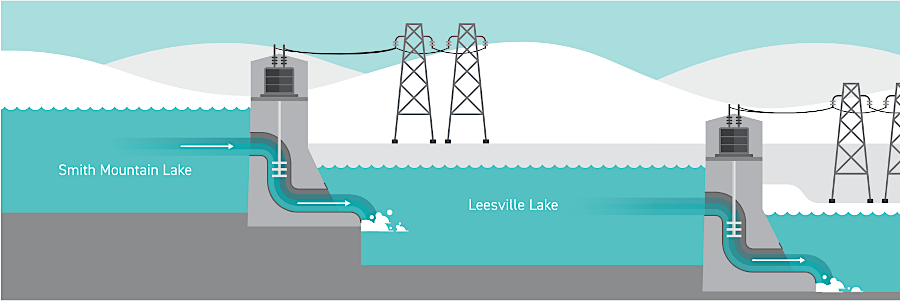

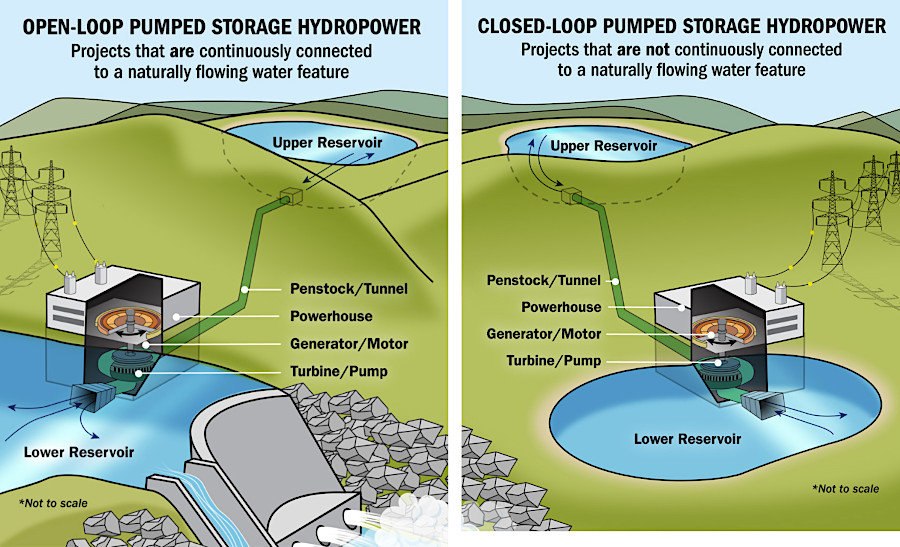

If a pumped storage project was built in Southwest Virginia using coal mines, it would be a "closed loop" project with two reservoirs that had no connection to an existing waterbody. Siting of a closed loop project should be easier, since no natural stream habitat would be flooded to create the two reservoirs. The environmental impacts of "open loop" pumped storage projects, such as Smith Mountain Lake and Bath County Pumped Storage Station, are much greater since they utilize existing streams.

pumped storage requires at least two reservoirs, but one or both could be underground rather than on the surface

Source: Dominion Energy, Powering Southwest Virginia

A pumped storage project associated with utility-scale solar plants could stimulate the construction of new data centers in Southwest Virginia. The region offers low costs for land and labor, and officials at the state and local levels are highly-motivated to support new economic development.

There are advantages to building new data centers in Northern Virginia, which already has all the infrastructure required for transmitting "bits" worldwide, but rural areas are also attractive. Microsoft has already located a major data center in Mecklenburg County. If Southwest Virginia could provide a highly-reliable supply of 100% renewable energy, and if it had high-speed broadband capacity, the region might compete with Loudoun and Prince William counties for construction of future data centers.10

Local economic development planners dream of the possibility that green energy could stimulate the region into becoming "Silicon Hollow." The local governments were the first in Virginia to cooperate on attracting major industries by agreeing to share revenues, in hopes of luring Motorola into building a computer chip fabrication plant. They got the General Assembly to pass the Virginia Regional Industrial Facilities Act and created Commerce Park in Pulaski County. The localities in Southwest Virginia that belong to "Virginia's First Regional Industrial Facility Authority" plan to use that revenue sharing authority so the entire region will benefit, no matter where the pumped storage project is built.11

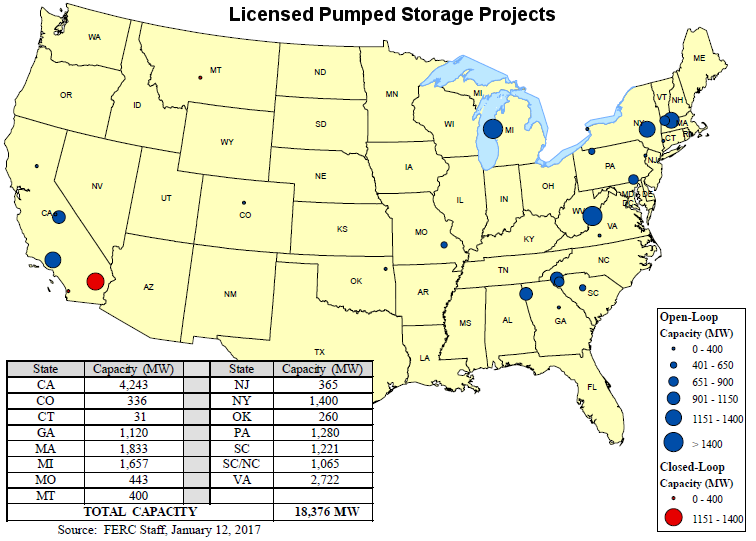

only California generates more electricity from pumped storage projects than Virginia

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Licensed Pumped Storage Projects Map

In September, 2017, Dominion Energy announced that its site selection process had identified two candidates, the old 4,000-acre Bullitt coal mine site in Wise County and a site near East River Mountain in Tazewell County. Dominion packaged the proposal with a claim that renewable energy would be use to pump water back to the upper reservoir, to enhance support from the general public.

Groundwater had naturally flooded the Bullitt Mine once coal mining operations ceased. By one preliminary estimate, four billion gallons of water filled the maze of rooms left underground after 19 billion tons of coal was removed between 1969-1997.

Dominion suggested the mine could provide a lower reservoir site in a closed-loop project. The lowest point in the mine was only 130 feet underground, so a surface reservoir would be located at a higher elevation rather than at the mouth of the closed mine. That Wise County project would produce just 150 MW of electricity.12

the Bullitt Mine is located just west of the Town of Appalachia in Wise County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

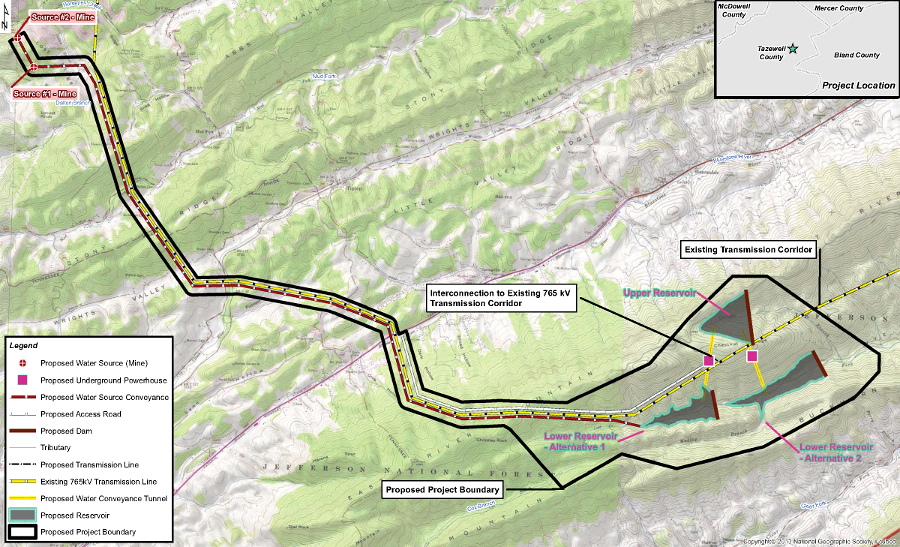

The other location, the Tazewell Hybrid Center project, would be on East River Mountain. Dominion Energy had previously acquired 2,100 acres for a wind project there that the utility later abandoned.

One option in Tazewell County was to build three generating units that could each produce 290MW (megawatts) of electricity. Water in the upper reservoir would drop 887 feet to the powerhouse generators, then be captured in the lower reservoir for reuse. The "water-based battery" could produce up to 2,540 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity annually.

An alternative was to build just two 223MW generators with a hydraulic head (distance to powerhouse) of 621 feet. The smaller alternative could generate 1,302 GWh annually.

To fill the reservoirs, Dominion Energy originally proposed to pump 6.5 billion gallons of water from an abandoned mine at Amonate. That source would also replace water as needed to compensate for evaporation. The pipeline would parallel an existing 765kV transmission line for most of the route between the flooded mines and the pumped storage reservoirs.

The Preliminary Permit Application submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for the Tazewell Hybrid Center stated:13

Source: Dominion Energy, Dominion Energy Hydroelectric Storage

Like the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center built by Dominion in Wise County, the two proposed locations were in the service area of another utility rather than in territory allocated to Dominion Energy. Dominion Energy could distribute the electricity via the PJM transmission grid to meet its customer needs, or simply sell the electricity at peak power prices to any other utility connected to the PJM grid.

Dominion Energy also could negotiate a deal to share/sell peak power from a new pumped storage facility to Appalachian Power, the largest utility serving Southwest Virginia. The two utilities already share ownership of the Bath Pumped Storage Project.

In 2019, Dominion Energy announced it would focus on the Tazewell Hybrid Center site on East River Mountain, and would stop planning for the alternative pumped storage facility in Wise County using water from the Bullitt Mine.

At the same time, the utility also abandoned plans to pump water from a mine at Amonate to supply the proposed lakes in Tazewell County on East River Mountain. Instead, it would explore getting the water to fill and replenish the reservoirs from Wolf Creek. The site was near the headwaters of the creek and flows were low, so it might require two years to capture enough excess water from the creek to fill the two reservoirs initially.

Though the Bullitt Mine site was not chosen, under the revenue sharing deal Wise County would still get 16% of the property taxes from the pumped storage plant if it was completed. As the host county, Tazewell County would get 22% of the property tax revenue. Buchanan, Lee, Russell and Scott counties would each get 16%, Dickenson County would get 10%, and the City of Norton would get 4%.14

the Tazewell Hybrid Center pumped storage project near East River Mountain would rely upon water from flooded mines near the West Virginia border

Source: Dominion Energy, Tazewell Hybrid Center Figures

The utility initially calculated that adding 1,000 MW of new pumped storage hydropower would cost $2 billion. In the 2020 Integrated Resource Plan, Dominion estimated the project would cost $2.3 billion but provide only 300 MW of storage capacity. Since the General Assembly had defined the project as being in the public interest, despite the low benefit/cost ratio the utility could still request the State Corporation Commission (SCC) to authorize construction - and add the $2.3 billion facility to Dominion's rate base, increasing authorized profits of the regulated utility.

In testimony to the State Corporation Commission, an energy expert reported that Dominion did not need another pumped storage hydropower (PSH) facility. Large-scale battery technology had developed to the point where it provided a less-expensive alternative. In addition, demand for electricity from Dominion's existing pumped storage plant in Bath County was projected to decline; no new facility in Tazewell County was required:15

Pumped storage was the most reliable technology for long-term energy storage, offering more than 100 hours of energy storage capacity. Even standard hydroelectric facilities can serve as batteries. In 2025 new powerlines connected Quebec with Massachusetts and New York. Energy planners anticipated that as solar and wind power increased in the United States, electricity could be delivered north to Canada at times of peak generation. That would reduce Hydro-Quebec's need to drain its reservoirs in order to run turbines at the dams; water could be stored for use when wind/solar generation declined.

By 2020, multiple competitors to pumped storage systems emerged. Short-term storage based on lithium-ion batteries was not viewed as feasible, due both to cost and the limited number of charge-discharge cycles that could be accommodated.

Alternatives included using excess electricity to lift weights, then rely upon gravity to release the mechanical energy stored by railroad cars with heavy loads at the top of a hill, a huge weight lifted into the air, or a column of water. Other options included compressing air or hydrogen in an underground reservoir rom which natural gas or salt had been removed, and heating a fluid or solid object with energy when it was in surplus.16

In 2024, Dominion Energy cancelled the Tazewell project. Regarding the company's 2,600 acres on East River Mountain, a company spokesperson said:17

The most recent pumped storage project to be completed in the United States is the Rocky Mountain Pumped Storage Hydroelectric Project near Rome, Georgia. It was licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 1977 but not completed until 1995. In 2026, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued the last necessary Federal permit to construct a 1.2 gigawatt pumped storage facility next to the Columbia River in the state of Washington. If completed, it would become the largest pumped storage plant in the country.

Rye Development also planned two other pumped storage projects, in Oregon and Kentucky. It expected to use low-cost electricity, available when there is a surplus from wind and solar facilities, to pump water into the upper reservoir.

The project used a closed loop design, with water moving between two new reservoirs. Water would be recycled between them, so the Columbia River would not be affected when the upper reservoir was drained to generate electricity. The Bath County and the Smith Mountain Lake pumped storage projects in Virginia built dams within natural stream valleys to create reservoirs, rather than excavate new artificial storage ponds.

The Washington facility was adjacent to major transmission lines, so the power plant could send electricity easily to customers in the Pacific Northwest and California. The project was expected to be profitable because it would provide long-term storage of the potential energy, allowing contracts to guarantee a reliable supply during discharge of the "battery" when electricity prices were higher:18

the two pumped storage projects in Virginia are open loop facilities, with reservoirs created by constructing dams in natural stream valleys

Source: US DEpartment of Energy, What is Pumped Storage Hydropower?

Pumped storage facilities are only one form of long-duration energy storage (LDES) projects. Increasing numbers of wind, solar, and other non-dispatchable projects generate electricity that exceeds demand at times, in part because the transmission grid is inadequate to distribute that electricity. Pumping water uphill is not the only way to capture the excess.

The most successful competing energy storage technology is lithium-ion batteries, which are particularly good at short-term discharge and relatively quick recharge. They dropped in cost 92% between 2010-2025, and were approaching just $100-per-kilowatt-hour (kWh) in cost. In 2024 Tesla's lithium-ion batteries in the Model S Long Range car stored 100 kWh of energy, providing a range of over 300 miles before recharge was necessary. Tesla's Megapack batteries were designed for utilities and large-scale commercial projects. Each unit stored 3.9 megawatt hours (MWh) of electricity, and by 2025 the company had deployed 10 gigawatt hours (GWh) of battery capacity worldwide.

Pacific Gas & Electric installed a 730 MWh Tesla Megapack to balance the electricity supply when demand peaked

Source: Tesla, Moss Landing Megapack (May 3, 2022)

Form Energy took the lead in developing iron-air batteries that could dispatch electricity for up to 100 hours. Unlike lithium-ion batteries, iron-air batteries are not likely to catch fire. Form Energy claims they can be built at 10% of the cost of lithium-ion batteries, and there is no shortage of iron compared to lithium.

The iron-air technology uses electrical current when there is an excess supply to create put powdered iron in its metallic state, without oxygen atoms combined. When customers need electricity, the iron-air battery reverses the process. Oxygen atoms are allowed to combine with iron to create iron hydroxide (rust), and that chemical process generates electricity.

Transportation agencies already use the same process to protect metal in bridges, applying a current to steel infrastructure in order to minimize corrosion. As described by a battery engineer:19

conceptual sketch of an iron-air battery facility adjacent to solar panels, creating a 24/7 dispatchable source of electricity

Source: Form Energy, Battery Technology

A third option is compressed-air energy storage. By 2025, there were three compressed-air energy storage (CAES) projects in the world. Excess electricity is used to force air into underground caverns at high pressure. When demand for electricity exceeds supply, the air is released to spin turbines and generate electricity at a power plant on the surface.

GEM A-CAES, a Hysdrostor project in California to store enough compressed air to generate 4,000 megawatt-hours, received a $1.76 billion conditional loan guarantee at the end of the Biden administration. It involved excavating a cavern 100 yards long, 50 yards wide, and 100 yards high. Turbines will deliver the electricity that can be produced by a 500 megawatt power plant, for an eight-hour stretch until recharge is required.

A key advantage of a compressed-air energy storage project is that 80% of the geology in the United States allows construction of the caverns, so batteries can be built near power plants with existing power lines or at transmission grid congestion points. However, the technology is relatively inefficient, with the first projects producing only 50% of the energy invested in compressing the air. In comparison, lithium-ion batteries deliver 90% and pumped hydropower projects deliver 80%.

To increase efficiency to 65%, the GEM A-CAES project planned to include a pool of water in the bottom of the cavern. That will maintain constant air pressure and enhance turbine efficiency. The water will also be heater when the cavern is filled with compressed air, and that heat will be utilized when the air is released. The expanding air cools, and without heating it the air would:20