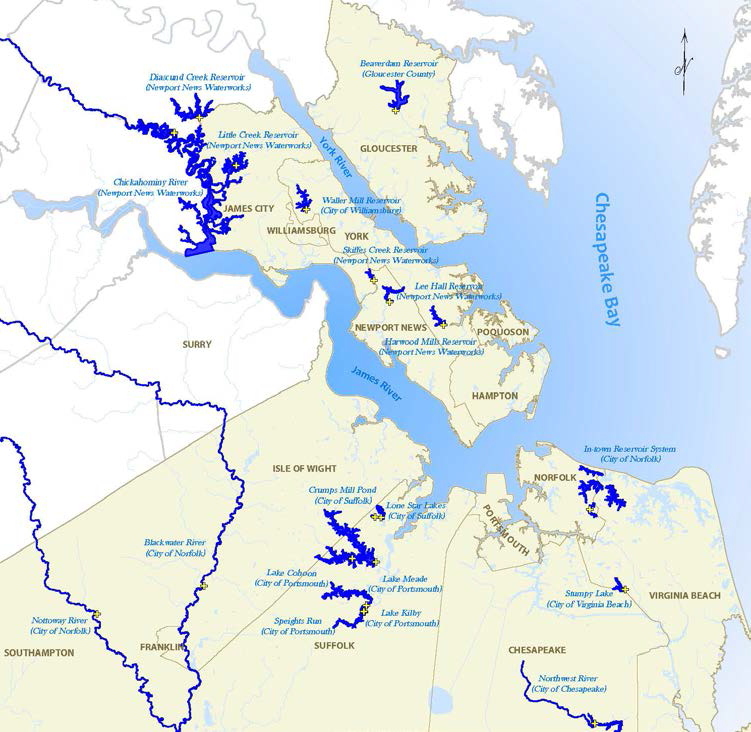

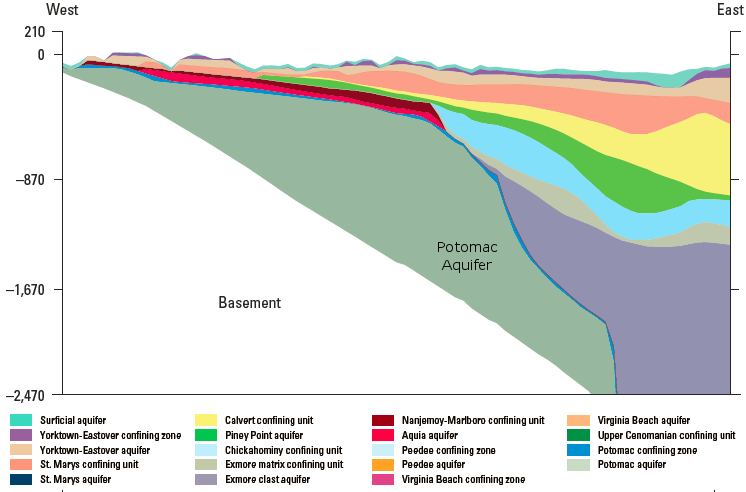

various reservoirs have been developed to capture surface water to supply customers on the Coastal Plain

Source: Hampton Roads Planning District Commission, Groundwater Withdrawal Permits (October 16, 2014)

various reservoirs have been developed to capture surface water to supply customers on the Coastal Plain

Source: Hampton Roads Planning District Commission, Groundwater Withdrawal Permits (October 16, 2014)

Today, we drink water droplets whose atoms have been many places.

Most of the hydrogen atoms in the water we drink have been around for over 13 billion years; they were created soon after the universe. The oxygen atoms may be younger, created as stars formed and then dissipated elements into space, but are at least 4.5 billion years old.

When the Earth formed 4.5 billion years ago, lighter elements such as hydrogen were located further away from the sun and froze into comets and meteorites. When those objects with pre-existing water molecules collided with the Earth, they brought many of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The water in comets was in the form of ice and contributed about 10% of the water as the earth coalesced. Water in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, chemically bound with other elements in clay minerals, provided the majority of the water when Earth first formed and during a Late Heavy Bombardment.

Water that ended up in the earth's mantle has reached the surface through volcanic eruptions. Intermittent outgassings of water vapor from the earth's interior redistributed the lighter molecules to the surface. Within the first 100 million years of earth's existence, liquid water may have flowed. Oceans may have been present on earth before the moon was formed.1

For over 4 billion years, the original water in the atmosphere has fallen back to the surface as raindrops, drained to the oceans, and evaporated again into the sky. The hydrologic cycle has been repeated over and over and over and over again.

However, the water molecules we drink may be as young as just a few hours old. "Old " water molecules may have broken up into separate hydrogen and oxygen atoms, while other hydrogen and oxygen atoms combined to form "new" water molecules.

Some water can be trapped in bedrock, interrupting the hydrologic cycle. Perhaps the oldest water identified on earth is around 2 billion years old. The water oozed from Precambrian bedrock after miners dug 3 kilometers deep in a zinc/copper mine in Ontario, Canada. Scientists determined the age by measuring the accumulation of noble gases formed by radioactive decay.2

In every cup of water could be an H2O molecule that once eroded the ancient Appalachian Mountains 300 million years ago, or was slurped up from a mud puddle by a dinosaur wandering through the Culpeper Basin 100 million years ago, or was briefly incorporated in a Pennsylvania ice sheet that melted 18,000 years ago.

Once life evolved on earth, some of those water droplets have been taken up by plant roots and then evaporated from leaves. Through "transpiration," water is released as vapor from pores in the leaves (stomata) back into the air. Other water molecules that may be swirling in your cup of coffee may have been swallowed by animals and excreted back into the environment.

Since humans developed urban centers in Virginia, especially in the last 200 years, some of those water droplets have been cycled through human bodies, flushed into sewers and septic tanks, and re-entered the groundwater or streams to be recycled again. Are the water droplets that we drink today contaminated from all the past experiences?

The H2O molecules in our glass of drinking water have traveled through the air, ground, streams, and oceans over the billions of years since the earth formed. Odds are excellent that the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in every drop of water that we drink have previously traveled through the intestines of fish, deer, ducks, and maybe even a few humans - but ancient contamination has been transformed, as the atoms have combined and disassociated into different molecules.

the water in a modern cup of coffee might have been swallowed previously by dinosaurs

Source: Bureau of Land Management, Big Water Visitor Center

Molecules of water contaminated more recently are still likely to be contaminated. Except for the very few people who live at the headwaters of a stream on a watershed divide, everyone lives downstream. Odds are good that something, and someone, absorbed and then excreted the water that they are drinking - and did so within the last two weeks.

Between animals in the woods and people in various forms of communities, many of the current H2O molecules go from mouth to toilet to mouth to toilet to mouth... getting recycled over and over.

Residents who live in Blacksburg, such as students at Virginia Tech, drink water from the New River. That water has been "used" in North Carolina and in Virginia communities upstream. Residents in Virginia Beach drink water from the Roanoke River, as well as other sources. Droplets from the Roanoke River could have been processed through various types of intestines in Salem, Roanoke, Altavista, Brookneal, Martinsville, Danville, South Boston, and Halifax.

During a trip from mountain to ocean, water droplets in streams can get clean naturally after traveling some distance. Inorganic contaminants (dirt particles, in particular) settle out when a stream slows down in eddies behind rocks. Settling also occurs when the gradient of a stream decreases and water travels slowly, when it enters a lake or reaches the relatively-flat Coastal Plain.

When water droplets are exposed to ultraviolet rays of the sun or high levels of oxygen after falling over a rock, the DNA of bacteria and viruses is degraded. With enough rapids and enough time, most biological contaminants can be removed.

sunlight and oxygen help purify water droplets in the Potomac River at Great Falls

H2O molecules absorbed by a plant root will be transported to the leaves and evaporated back into the atmosphere. Transpiration removes water from streams, shifts H2O molecules from liquid to vapor form, and releases it as water vapor in the atmosphere. Transpiration sterilizes the water in the process.

Water pollution is a modern phenomenon in Virginia. Virginia has areas of heavy metal concentration, but contamination of surface drinking water sources in Virginia by ore deposits is uncommon. Near the uranium ore body in Pittsylvania County, perhaps Virginia's richest mineral deposit, the water in nearby wells is drinkable rather than radioactive.

Native American population levels were low, and water contamination by their human wastes were not a major health issue except right at a town. People scooping water directly from a stream did not ingest an unhealthy dose of pathogens from animal and human wastes such as Giardia and other microscopic parasites, or water-borne viruses such as rotavirus and norovirus. "Raw water" was once healthy.

Today humans are concentrated in such density that natural processes can not clean our wastewater before the next community downstream plans to use it for drinking water. As far back at 4,000BCE (Before Common Era), humans were treating their drinking water to improve the taste and odor. Egyptians were adding alum to reduce contamination by 1,500BCE.3

Urbanizing and suburbanizing counties are exacerbating "natural" pollution by removing massive amounts of natural habitat. Natural processes that removed pathogens and sediment have been lost as impervious surfaces have been added.

New River, downstream from Eggleston (on the way to being used in West Virginia, and all the way to New Orleans...)

Prior to the arrival of European colonists, wildlife (deer, geese, mice, frogs, fish, etc.) in natural areas would rarely be concentrated enough to create sufficient waste to affect water quality. Predators ensured the animals stayed separated from each other, or moved on. As water ran down natural streams, exposure to sunlight/oxygen soon killed most harmful bacteria and viruses excreted by wildlife. However, today many once-natural areas have been developed as farms and subdivisions.

This transformation of habitat has crowded wildlife unnaturally into narrow strips of vegetation remaining along stream banks. In some cases, geese and deer populations have skyrocketed as subdivisions and office parks have provided new habitat. When concentrated unnaturally, wildlife waste can become a high percentage of the E. coli bacterial contamination found in some stream segments. Some analyses of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL's) of pollution that Virginia streams can absorb have identified places where bacteria coming from wildlife (especially geese) reduce the water quality below acceptable levels, and cause a stream segment to be classified as "impaired" under the Clean Water Act.

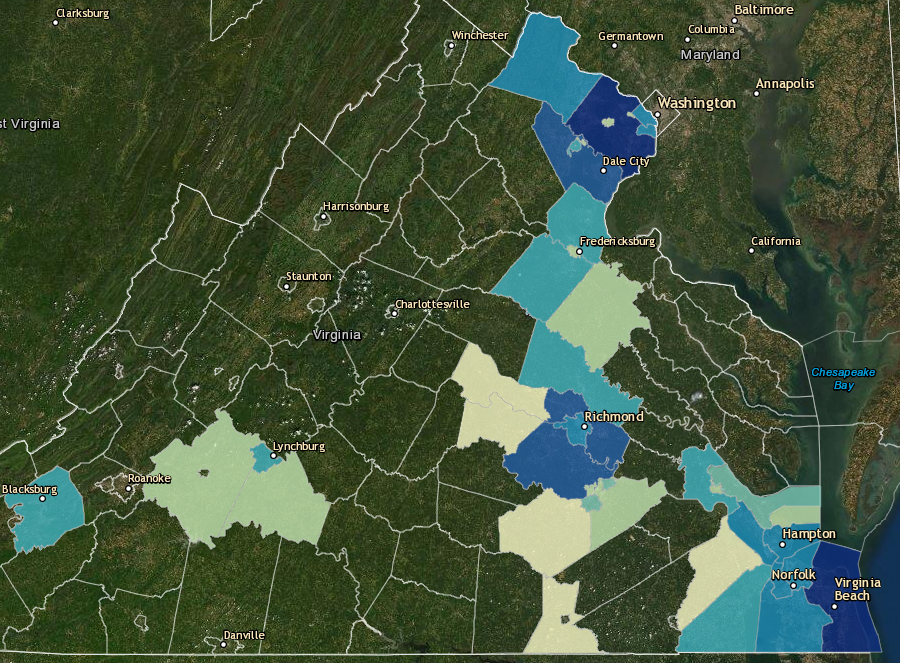

Various reservoirs have been developed to capture surface water to supply customers. In Hampton Roads, urban areas also rely upon groundwater and a direct pipeline to a reservoir that stores Roanoke River water on the Piedmont.

It is no longer safe to drink untreated water from any surface source in Virginia. The days when water could be piped directly from a river or a spring to houses, without concern about quality, are gone. Some individual houses still trust their spring or creek, but water systems that serve communities - even trailer parks in rural areas of the state - must treat the water so it meets minimum Federal Safe Drinking Water Act standards.

Norfolk water sources (including several outside the political boundaries of the city)

Source: City of Norfolk 2010 Water Quality Report

Many Virginians do not drink treated water. Nationwide, 13% of people rely upon private wells where water is pumped from an underground aquifer to faucets within a house, with no chlorine added to kill bacteria.4

Most private well owners are residents who live away from urbanized areas serviced by a public water system. Residents who drill individual wells to supply water for individual homes rarely include any system to purify water with chlorine, or fluoridate the groundwater to protect teeth.

Water from individual wells may go through a water softener to remove iron, or to remove calcium and replace it with sodium (creating "soft" water). Replacing calcium ions with sodium ions - provided by the salt that residents put into the water conditioner - helps soap lather, and minimizes the buildup of calcium scale that can clog pipes.

water softeners replace calcium atoms with sodium to reduce the "hardness" of water

Under the 1974 Safe Water Drinking Act, the Environmental Protection Agency is the Federal agency with responsibility for protecting nearly 150,000 public water systems in the United States. By EPA's definition, public water systems "provide water for human consumption through pipes or other constructed conveyances to at least 15 service connections or serves an average of at least 25 people for at least 60 days a year."

In Virginia, EPA does not approve new waterworks operators or oversee public water systems directly. Instead, the Virginia Department of Health has primary responsibility for compliance with the Safe Water Drinking Act requirements.

The Virginia Department of Health maintains a database of over 2,800 public water systems that provide water to at least 25 people for 60 days a year. There are over 160 public water systems in Prince William County, including gas stations and rest stops on I-66 as well as utilities that purchase treated water from Fairfax Water and the City of Manassas. Over 7,000 sites have a unique "PWSID" number, but most do not qualify as active public water systems.

The Office of Drinking Water (ODW) is responsible for oversight of the systems and ensuring owners taker corrective action if water quality standards are not met. In 2020, 2% reported dangerous levels of contamination that could threaten human health, and the state agency focused on correcting problems at 35 "serious violators."

Two concerns are the level of lead in drinking water and the presence of trihalomethanes (TTHM). Drinking water that leaves a treatment plant can dissolve lead as it travels through old pipes. Chemical treatment can reduce the potential of leaching out the lead. Trihalomethanes are a by-product of disinfecting drinking water with chlorine. Adding ammonia in the treatment process is on technique, while some public water systems have eliminate chlorine and switched to membrane filtration and ozone to kill bacteria.6

community waterworks utilizing membrane filtration

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Waterworks Treatment Techniques

Drinking water treatment plants process raw water taken from wells, rivers, or reservoirs, then process that water in a purification plant. After treatment, the plant will pump water clean enough for humans to drink through a network of pipes to customers.

Fairfax Water processes raw water from the Occoquan Reservoir at the Griffith plant (blue circle) without chlorine, by using membranes to filter particles and ozone to kill bacteria

Source: ArcGIS Online

The quality of the raw water affects the processing required to meet the Safe Drinking Water Act standards, and stay below the Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL's) established by EPA. When a community's drinking water system uses clean water from the headwaters of a stream, the cost to treat that water and meet state/Federal requirements are lower.

"Source water protection" efforts are designed to keep pollution out of water supplies, so the treatment of the water can be minimized. New York City has established the classic example of source water protection, buying property in the Adirondack Mountains to maintain a relatively-pure water supply. By blocking pollution from getting into the water in the first place, New York has avoided the cost of constructing expensive water treatment plants. Roanoke has, at times, blocked recreational use of the Carvins Cove reservoir watershed in order to prevent pollution from eroding soil or boat motors.

the City of Roanoke purchased the watershed draining into Carvins Cove and blocked development, to maximize source water protection

Source: US Geological Survey, Daleville 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013, Revision 1)

When a community's drinking water system uses clean water from the headwaters of a stream, the cost to treat that water and meet requirements are lower. Richmond is downstream of Lynchburg and other communities on the James River. The raw material that will end up in Richmond's drinking water system will require more treatment, compared to the treatment required to process raw water for a community located near the headwaters of the James River (such as Monterey, in Highland County).

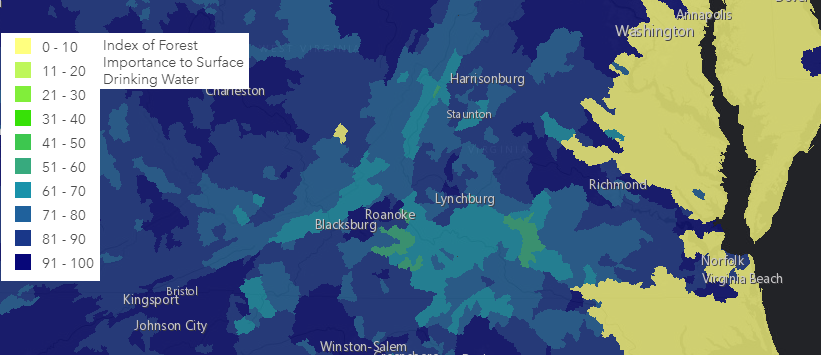

the US Forest Service Forests to Faucets project mapped where forests are most important for surface drinking water quality and quantity

Source: US Forest Service, Surface Drinking Water Importance Web Map

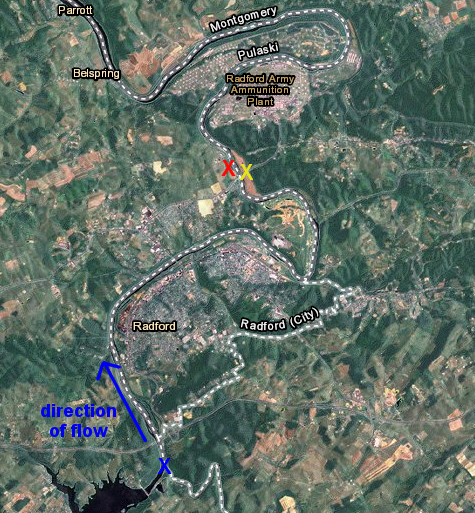

Radford withdraws water from the New River upstream of town, and discharges its wastewater downstream. Radford spent extra money to locate its wastewater discharge point downstream of the raw water intake for the Blacksburg-Christiansburg-VPI Water Authority.

That design helps minimize the cost of treating water to meet Safe Drinking Water Standards, and helps to generate greater public confidence in the quality of the drinking water. Go further upstream of Radford's intake, however, and you will see wastewater discharged from Dublin, Pulaski, Galax... Nearly every Community Water System has an intake located downstream of someone else's waste discharge pipe.

the City of Radford gets raw water for its drinking water plant from a site on the New River (blue X) upstream of its discharge point for wastewater (red X) - and discharges downstream of the drinking water intake for the Blacksburg-Christiansburg-VPI Water Authority (yellow X)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

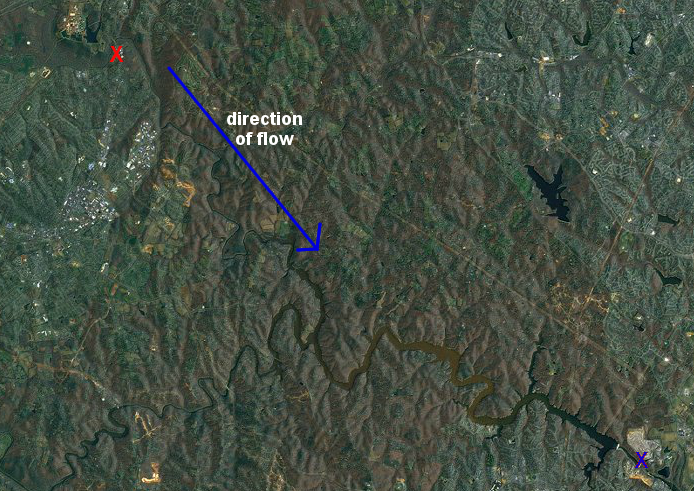

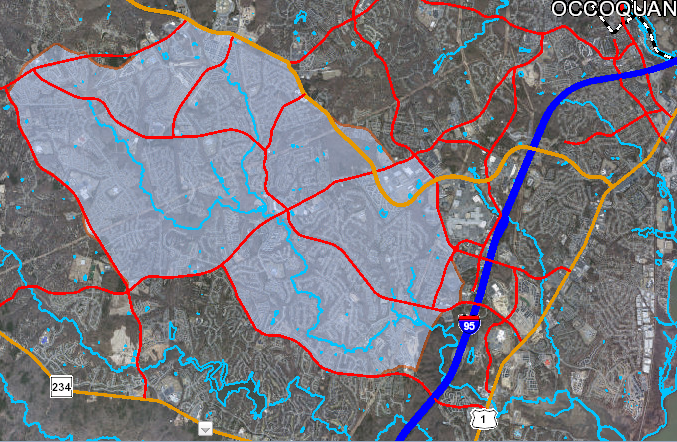

In Northern Virginia, Fairfax County ended up with the opposite pattern. One of its two drinking water plants has its intake on the Occoquan River, downstream of the massive Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) sewage treatment plant at Centreville. The drinking water plant was built in the 1950's, and then suburban development was permitted upstream. The drinking water in the Occoquan Reservoir was contaminated by inadequately-treated sewage until the state-of-the-art UOSA facility replaced 11 smaller wastewater treatment plants in 1978.

Fairfax Water draws half of its drinking water from an intake (blue X) downstream of the UOSA wastewater discharge point (red X), so residents in southern Fairfax/eastern Prince William drink water that has been flushed down toilets in Centreville/Manassas

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Proposals to withdraw 90 million gallons a month or more of water from rivers, streams, lakes, and other surface waters may require a Virginia Water Protection Permit issued by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). That state agency is responsible for coordinating the review process for withdrawals that also require approval by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC).

Virginia counties who meet the requirements of the state's Chesapeake Bay regulations typically focus on protecting the large, perennial streams that have water flowing in them all year. Developers may be allowed to destroy smaller, intermittent streams, placing them in pipes and filling the stream channel with sediment or pavement. However, the pollution that gets into small streams will inevitably wash down the channel, ending up at the intake of any drinking water plant downstream.

In 2009, EPA analyzed the Source Protection Areas, the area upstream from a drinking water source or intake that contributes surface water flow to the drinking water intake during a 24-hour period. The agency determined that 58% of the total miles of streams in the US that provide water for public drinking water systems are "intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams." Intermittent streams are streams containing water for only part of the year. Ephemeral streams flow only in response to precipitation events.

In Fairfax and Loudoun counties, the percentage of intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams was equivalent: 56%. In Prince William County, the percentage was 77%. Evidently EPA lumped the residents in the cities of Manassas/Manassas Park with the county of Prince William, and Lake Manassas relies upon even more intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams than the Occoquan Reservoir.7

Lake Manassas, T. Nelson Elliott Dam, and

City of Manassas Water Treatment Plant

Source: 1994 Color Infrared Digital Orthophoto Quarter Quadrangle (DOQQ)

of Thoroughfare Gap quad from GIS Center at Radford University

Lake Manassas and T. Nelson Elliott Dam

Source: Historic Prince William, Lake Manassas Dam - #263

Even a small community can severely pollute a small river, creating a headache for the drinking water plants downstream.

The Smith River below Philpott Lake is a top fishing destination for brown trout. Philpott Lake serves as a giant settling basin, so it enhances water quality downstream of the dam. Bassett, a community in Henry County that relied upon furniture factories, was finally "encouraged" by the state to clean up its wastewater.

Both Martinsville and Henry County avoided extracting raw water for processing into drinking water from the Smith River downstream from Bassett. Martinsville gets its drinking water from the headwaters of Jones Creek, while Henry County withdraws its water from Smith River three miles below Philpott Lake.

Henry County created a Public Service Authority in part to finance the cleanup. The communities downstream of Bassett are the beneficiaries of the pollution control, as are the fish, wildlife, and recreationists who use that stretch of the Smith River.

Drinking water systems with protected sources can be affected by industrial accidents that release pollutants upstream. Even individual wells can be threatened by crashes on highways that release contaminants from tanker trucks, as residents in Roanoke County discovered in 2014 after a truck crash spilled over 4,000 gallons of embalming fluid. The formaldehyde, methanol, and ethanol in embalming fluid are water-soluble, so the Virginia Department of Health advised nearby residents to avoid drinking the water from their wells and the truck's insurance company provided five-gallon containers of water as an alternative.8

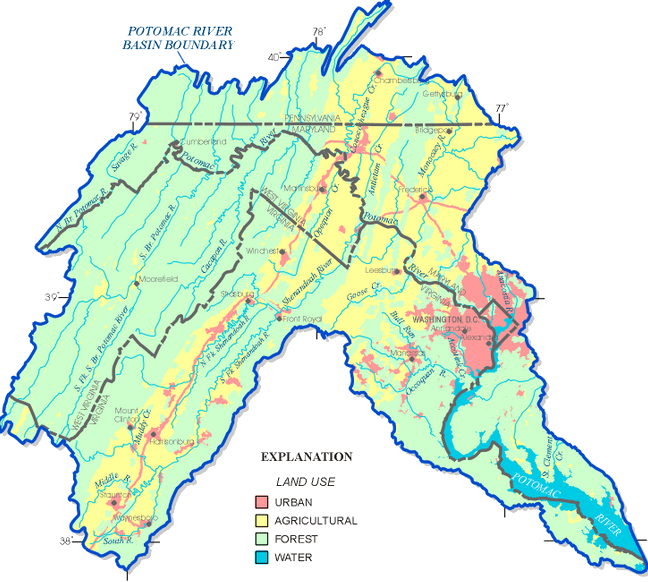

much of the water in the Potomac River flows off forested mountains in the watershed, but Fairfax County assessed just the five miles closest to its intake pipe for its Source Protection Area study

Source: US Geological Survey, Summary of Pesticide Data from Streams and Wells in the Potomac River Basin (OFR 97-666)

Typically, raw water is purified into drinking water in several steps. Early in the process, settling basins are used to stop the flow of the raw water, allowing sediments to settle out. Alum is added the cause the many tiny particles suspended in the water to "flocculate," bunching together until the clustered particles are so heavy they drop to the bottom of the settling tank. The water is then exposed to chlorine or high levels of ultraviolet light radiation to sterilize the water. Some communities (such as the City of Chesapeake) use reverse osmosis systems to purify water.

Communities that draw their drinking water from wells rather than surface sources (i.e., rivers) must also process the water to ensure it meets Safe Drinking Water Act standards. Mount Jackson has the ability to draw water from seven municipal wells, two of which have high levels of nitrates and one of which has a high level of iron. In 2014, the town chose to build a water treatment plant that would allow blending of water from different wells, to ensure iron and nitrate levels would be low in the final product.9

Source: Friends of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, NSVRC Presents: The Northern Shenandoah Valley Water Supply Plan

Drinking water plants import raw water and export clean drinking water from the plant to final customers. Drinking water distribution systems include water towers, in part to store water for peak demands but also in large part to maintain pressure in the system. After pumping water up into the tanks, gravity will push the clean drinking water through the pipes to customers - even after hurricanes, when electricity might be out.

water tank at McCoart Government Center, Prince William County

In contrast, wastewater travels from the customers to the sewage plant through unpressured pipes. Infiltration of groundwater into sewage pipes is a problem because it forces the wastewater facilities to use more chemicals/electricity to treat the additional volume. Infiltration of groundwater into the drinking water system is a threat to human health, so the pipes in the drinking water distribution network are maintained at a higher level of reliability.

Drinking water often travels through pressurized pipes. In such cases, a leak will result in water escaping the pipe, but there's less chance of contaminated groundwater entering against the pressure gradient.

Since all of Virginia experiences freezing temperatures at least occasionally, the pipes are underground - unlike the electricity distribution network, where the maze of overhead wires exposes clearly the geographic pattern of a few centralized sources providing electricity to many individual customers.

groundwater pumped to the surface for use in rural areas can be contaminated by waste from cattle, outhouses, or application of fertilizer/pesticide/herbicide on farm fields nearby

There is an economy of scale in creating safe-to-drink water, comparable to the economics of producing electricity. Drinking water treatment plants mimic natural processes to strip contamination from raw water. Making water safe to drink involves using settling tanks, chemicals and ultraviolet light, to accelerate the decontamination that occurs naturally over longer distance/time.

New threats to water quality generate new expenses for treating water to ensure it meet Safe Drinking Water Act standards. Until 2024 there was no Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) in drinking water to limit the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). They were also known as "forever chemicals," because their especially persistent carbon-fluorine bond prevented degradation into smaller molecules.

Proposals for different PFAS standards produced different cost estimates. When the Environmental Protection Agency planned to set Maximum Contaminant Level PFAS standards at 4ppt (four parts per trillion), the Federal agency projected that utilities would have to spend $777 million to $1.2 billion to comply. The American Water Works Association had a far different estimate, and suggested costs could reach $37 billion. However, a Maximum Contaminant Level standard of 10ppt would affect only 2% of the utilities supplying public drinking water.

About 50% of Americans get their drinking water from a source that is downstream from at least one wastewater treatment plant. Wastewater treatment does not remove PFAS; instead, it increases the concentration of the pollutant in the effluent that is discharged after treatment.10

The treatment process in drinking water treatment plants is very similar to not only natural processes, but also to how sewage is treated in wastewater treatment plants. Solids are removed, chemicals are added/UV light used to kill protozoa and disrupt the DNA of bacteria/viruses, and the final product is inspected before being released. Water that leaves a public drinking water plant is pure enough for human consumption. Once it enters the pipes, there is a risk of contamination. In rare cases, cracks in the drinking water pipes (created by settling, or tree roots) may allow contaminated groundwater to get into the drinking water distribution system. Most often, however, contamination is introduced at the very end of the distribution process, especially in residences with lead or copper pipes.

When the drinking water gets to houses, residents may percolate it through coffee grounds, mix it with frozen lemonade, or drink the water straight. However, we also use drinking water to cook pasta for 8 minutes at a roiling boil. We use drinking water to take showers, clean laundry, flush away waste in toilets, and water lawns. In many Virginia communities, we use drinking water to supply hydrants for fighting fires. As little as 5-10% of the "drinking" water produced by the Fairfax County drinking water plant on Route 123 near Lorton will actually be swallowed by humans.

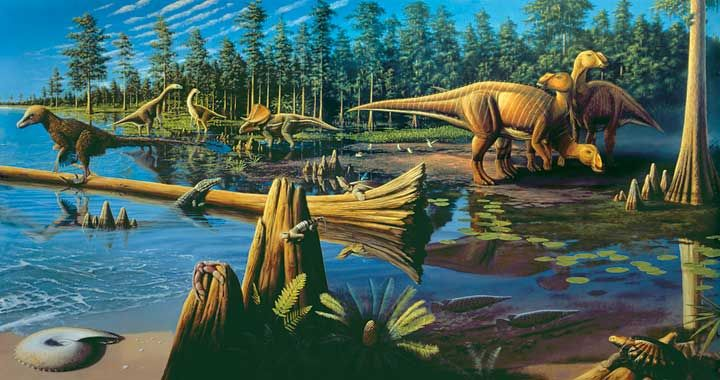

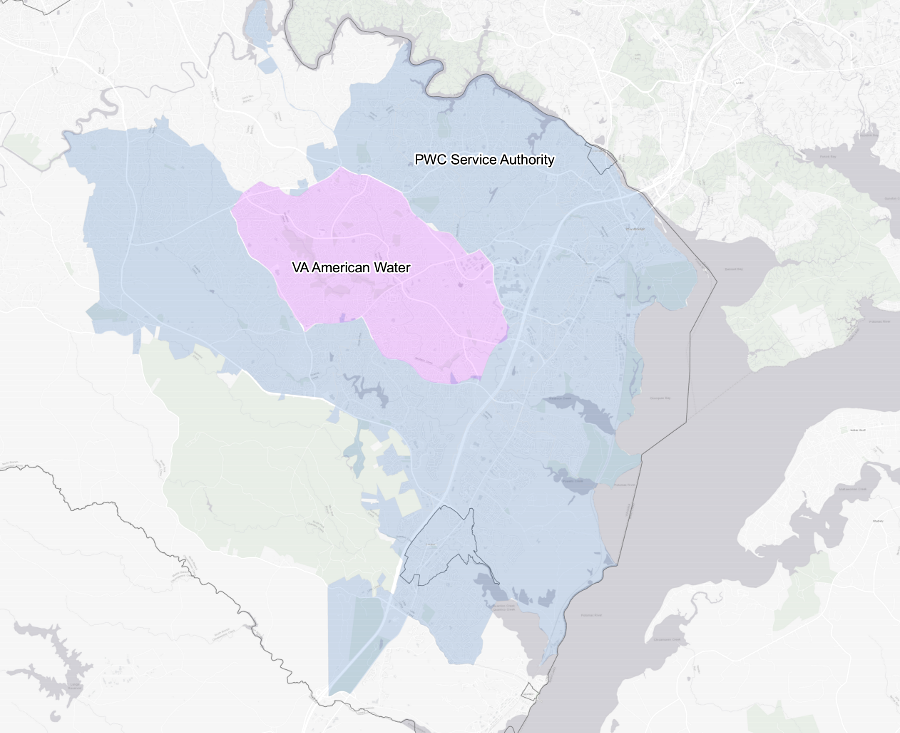

Virginia-American Water Company service area (Dale City, in Prince William County)

Source: Prince William County Mapper

Different utilities charge different fees for the water that they sell - and some water companies are for-profit businesses. A comparison produced by the Fairfax Water utility in 2010 showed that Fairfax Water charged the lowest rate of any utility in Northern Virginia.11

In 2010, the Virginia-American Water Company charged its customers in Prince William County 160% higher rates than Fairfax Water charged its customers in southern Fairfax County - though the two utilities were selling exactly the same water. Fairfax Water produced and shipped processed drinking water across the Occoquan River to the Virginia-American Water Company, which then distributed that water in Dale City. Fairfax Water sold the same water, primarily from the Frederick P. Griffith Water Treatment Plant, in southern Fairfax County.

Why the difference in rates? The Virginia-American Water Company is a for-profit, investor-owned utility - a private company - while Fairfax Water is a non-profit public utility. The State Corporation Commission must approve rates set by private utilities, so the private company does not have total freedom in setting its fees to customers. It justifies the higher rates in part by claiming its costs for maintaining infrastructure and billing systems are different from the costs in Fairfax County.

Fairfax Water's treated water is distributed in eastern Prince William by a public agency (Service Authority) and a private utility (Virginia-American Water)

Source: Prince William County Emergency Operations Center, Eastern PWC Municipal Water Service

Even non-profit municipal water systems are likely to increase rates on customers. The City of Portsmouth system relies upon pipes installed when Ulysses S. Grant was president. The valves were replaced in the 1980's, but starting in 2013 the city began a $100 million project to replace many of the 120-year old pipes.

Funding for the maintenance will require annual rate increases of 5-7% for five years. Another $65 million might be needed for another 20 years of additional pipe replacement. The city manager noted that the pace could be increased, but the costs were funded by water users (ratepayers):12

starting in the 1920's, Lone Star Industries dig pits along Chuckatuck Creek to excavate marl for cement, and since 1977 Lone Star Lakes have been part of the City of Suffolk water supply

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Though there are economies of scale, communities that developed independent water systems have been reluctant to integrate them into regional public service authorities. In the 1960's, Fairfax County purchased (through condemnation) the private company that supplied water to the City of Alexandria. Since then, Fairfax Water has extended its service to supply much of Prince William County, and then acquired the municipal systems created by the cities of Falls Church and Fairfax. Only the City of Manassas and Loudoun County have been able to maintain independent water systems in the region.

Small communities struggle to manage their drinking water and sewer infrastructure. In some months, Strasburg was able to bill for only 60% of the water that it treated and distributed, and the other 40% disappeared through leaks in the pipes or to unmetered customers. The wastewater flowing to the treatment plant occasionally doubled within one month though the number of customers remained the same, indicating substantial amounts of inflow and infiltration.

However, the town determined that it could not afford to hire a consultant with modern technology to assess where pipes had cracked. In 2014, the Town Manager reported that the public works department needed to purchase its own cameras to identify leaks in the underground systems:13

The Town of Waverly struggled to maintain its municipal water system until selling it for $2.2 million to a private company, Virginia American Water, in 2022. The sale was negotiated over three years. Sale of the water system enabled the town to reduce its annual costs and avoid the need to borrw money to improve the pipes and water meters. The sale also freed up Public Works staff to perform other maintenance duties.

Virginia American Water had to fund a substantial upgrade to the system, but agreed to limit rate hikes for two years. The State Corporation Commission had to approve the transfer, and future rate hikes must be approved by that state agency.14

The ratepayers will see higher fees as Virginia American Water recovers its investment and pays dividends to owners of shares in the private company. From a political perspective, Waverly Town Council members will be able to complain along with town residents to the State Corporation Commission about those future rate hikes. The elected officials will be able to claim that the rate hikes by Virginia American Water are not higher taxes imposed by the Town Council.

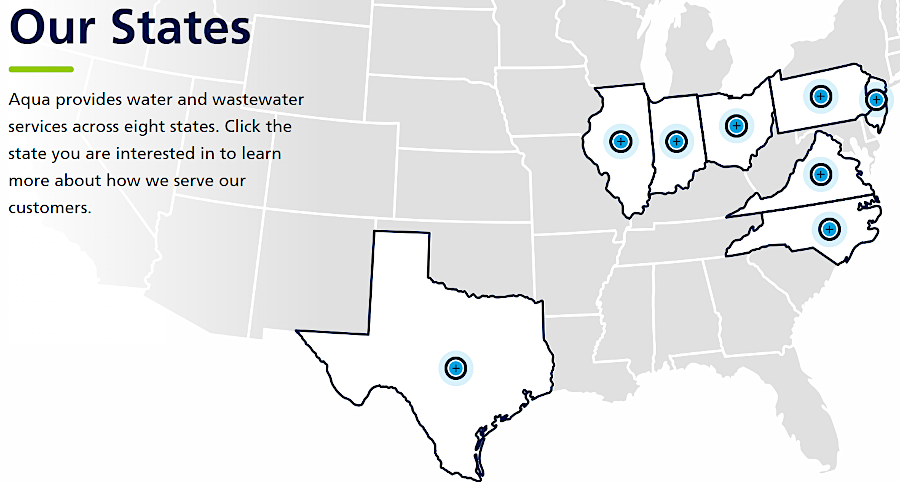

in addition to municipal utilities, for-profit private companies such as Aqua Virginia provide public water

Source: Aqua Virginia, About Us

In 2023, the private utility Aqua Virginia requested that its 27,000 customers pay significamtly higher water rates. The for-profit utility operated 191 water systems and 9 wastewater systems in 37 Virginia counties, and had 400+ wells and 750+ miles of of pipe. It told the State Corporation Commission that profits had dropped below the state-authorized level. Operating costs post-COVID had increased, and Aqua Virginia had invested $30 million since 2020 to upgrade wells, meters, filters, and other facilities. As a private corporation, it had to borrow money at commercial rates; it could not sell tax-free municipal bonds.

After a year-long review, the State Corporation Commission approved price increases ranging between 31%-43%.15

Source: Prince William Conservation Alliance, Water Water, will there be a drop to drink

different aquifers defined underneath the Coastal Plain, between Richmond-Cape Charles

(Potomac Aquifer is lowest one, just above crystalline basement rock)

Source: US Geological Survey, Simulation of Groundwater Flow in the Coastal Plain (Scientific Investigations Report 2009-5039)

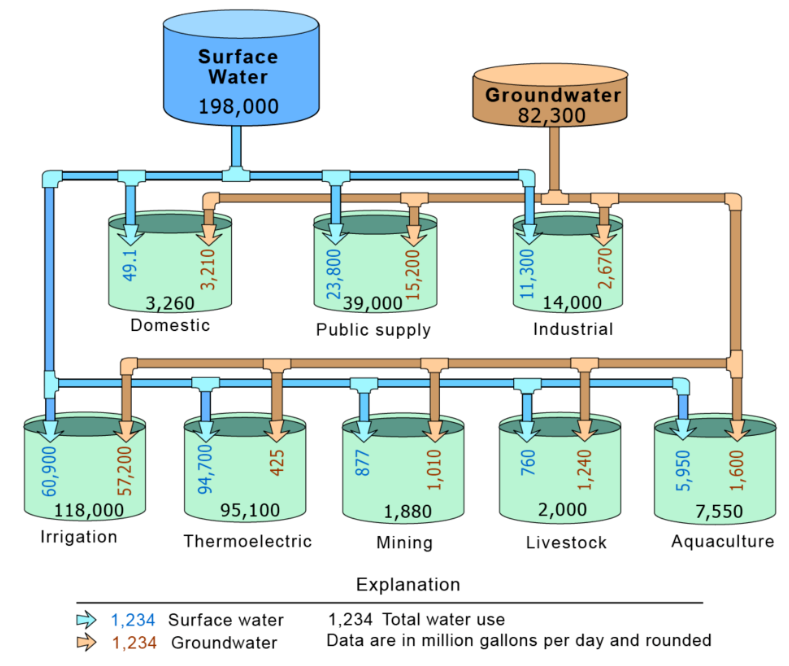

most surface and groundwater is used for purposes other than drinking water

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Groundwater Use in the United States (2015)