Off-Stream Storage Reservoirs

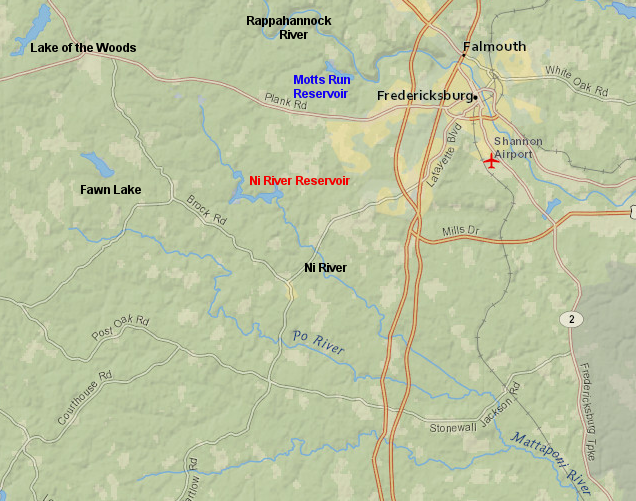

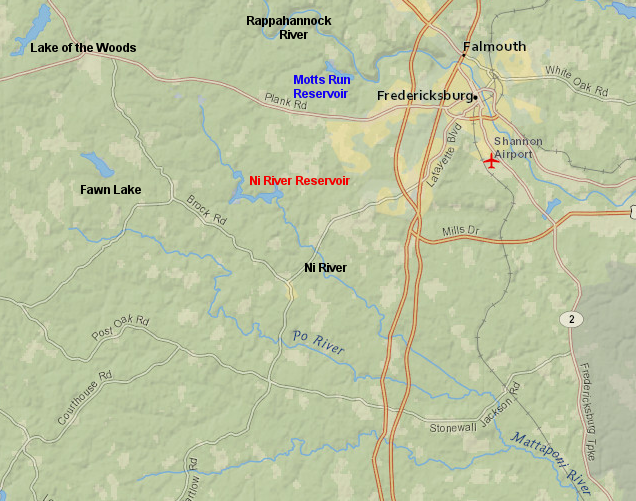

the dam creating the Ni River Reservoir was built across the river's main channel, but the dam for the Motts Run Reservoir was located on a small tributary of the Rappahannock River to create an off-stream storage reservoir

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Until the 1980's, drinking water reservoirs in Virginia were constructed by building dams across the main channel of rivers and large streams. Engineers chose locations where upstream flow from above the dam would be large enough flow to offset withdrawals from the reservoir, or where increased flows during winter (when plants are not transpiring rainfall) could refill a reservoir after drawdown during the low flows of summertime.

Such dams blocked shipping and the migration of anadromous fish in Tidewater. The economic benefits of an increased water supply offset the adverse economic and environmental impacts, but after passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970 there was greater emphasis on considering the tradeoffs.

In 1974, the Soil Conservation Service of the US Department of Agriculture built a dam across the Ni River to create a new 417-acre flood control/drinking water reservoir for Spotsylvania County. The new reservoir was large enough to provide a steady 4 million gallons/day of raw water throughout the year, and Spotsylvania County later upgraded the Ni River water treatment plant to generate as much as 6 million gallons/day of treated drinking water during times of high demand.

The 45-high dam across the Ni River was the last dam built directly in the channel of a major stream in Virginia. Also in 1974, Congress blocked the proposed Salem Church Dam. In 1968, Congress had authorized a dam 206 feet high, to be located five miles upstream from Fredericksburg. It would have created a reservoir twice the size of Lake Anna and converted the Rappahannock River below Kellys Ford from a free-flowing stream into a flatwater reservoir.1

Since 1933, Fredericksburg had discussed building the Salem Church Dam to replace Embrey Dam and its diversion of raw water through the Rappahannock River Canal to the Kenmore Water Treatment Plant. Costs to repair Embrey Dam to meet dam safety and fish passage requirements were high, and a new dam at the Embrey Dam site would not increase the water supply sufficiently to meet expected demand. The debate over the Salem Church Dam made clear that environmental concern about riparian areas and wetlands, plus public support for maintaining free-flowing rivers, required Fredericksburg to find another way to meet its increasing demand for drinking water.

The obvious water source for the city was the Rappahannock River, even if a new dam across the main channel was no longer acceptable. The solution was to use the river's water, but to avoid building a new dam that would block the flow of the Rappahannock River.

In 1965, even before Congress finally blocked plans to build the Salem Church Dam, Fredericksburg constructed a 100-foot high dam across a small Rappahannock River tributary known as Motts Run. Building a new 160-acre drinking water reservoir for the city on the small Motts Run tributary minimized the number of wetland and riparian acres that would be affected.

The Motts Run watershed of only 6,834 acres could not supply the 24 million gallons/day needed by the city, but that was never the plan. Fredericksburg obtained permits to pump water out of the Rappahannock River, which was supplied from a 1 million acres watershed upstream, during periods of high flow.

The raw Rappahannock River water was stockpiled in the Motts Run reservoir until it was needed. The 1999 completion of the Motts Run Water Treatment Plant allowed Fredericksburg to remove Embrey Dam and close the outdated Kenmore Water Treatment Plant.2

Motts Run Reservoir was built originally for use by just the City of Fredericksburg, but Spotsylvania County negotiated an agreement to build another off-stream reservoir upstream and expand the capacity of the Motts Run Water Treatment Plant

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Spotsylvania County was not part of the original Motts Run project. The county and the city of Fredericksburg were unwilling to cooperate while competing to attract retail and commercial development, and annexation of county land by the city intensified the rivalry.

Spotsylvania recognized that full "build out" development based on growth projections in the county's Comprehensive Plan would result in a demand for treated water that exceeded what the Ni River Reservoir could provide. In 1988, the county proposed to build another drinking water reservoir with a dam across the main channel of the Po River, creating a new water supply independent of the Fredericksburg system.

The proposed Po River Reservoir would have submerged 312 acres of wetlands on the edges and tributaries of the river. The US Army Corps of Engineers delayed Federal approval for destroying the wetlands (which was required under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act) for five years.

Spotsylvania County and the City of Fredericksburg finally agreed to consolidate planning and infrastructure for water supply, putting aside their history of hostile annexations and competition for commercial development. The county ended its efforts to dam the Po River, and Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania agreed to cooperate in building a new off-stream reservoir.3

a dam on the Po River near Route 208 would have drowned the river valley up to Wrights Pond and the Gladys Run tributary up to Jennings Pond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

They chose to build a dam across Hunting Run, a small tributary of the Rapidan River. The small amount of rain falling in the 4,620 acre Hunting Run watershed above that dam site does not fill the 420-acre reservoir. Instead, the Hunting Run Reservoir - like the Motts Run Reservoir - is filled by pumping water from a nearby stream with a larger watershed.

Above the site where water is pumped into the Hunting Run Reservoir, the Rapidan River watershed is 95 times larger (439,000 acres) than the Hunting Run watershed. Up to 20 million gallons/day can be pulled from the Rapidan River when there is adequate flow, while always leaving the minimum in-stream flow in the Rapidan River channel to support fish and wildlife.

Hunting Run Reservoir was designed to supply drinking water to Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County, but there is no water treatment plant there and no pipe to carry raw water from the Hunting Run Reservoir to any other water treatment plant. Instead, when demand for drinking water reaches a certain level, the water stored in Hunting Run Reservoir is released back into the Rapidan River (using the same pipe that pumps water into the reservoir during periods of high flow).

The released water then augments the natural flow of the Rapidan River, flows downstream into the Rappahannock River, and ultimately reaches the intake of the Motts Run Reservoir. Water is treated at the Motts Run water treatment plant, and not released back into the Rappahannock River.4

The extra water released from Hunting Run Reservoir is removed from the Rappahannock River and pumped into the Motts Run Reservoir, adding to the stored supply feeding the Motts Run Water Treatment Plant. Throughout the 10-mile downstream journey from Hunting Run to Motts Run, the released water supplements the natural flow in two rivers and provides benefits to fish and wildlife during drought periods.

Using the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers as a pipeline is cost-effective, but not 100% efficient. During the trip downstream some of the released water evaporates, or infiltrates into the soil and then is transpired by plants.

water released from Hunting Run Reservoir flows down the Rapidan/Rappahannock rivers, to be pumped into the Motts Run Reservoir and processed by the water treatment plant there

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Lake Mooney Reservoir is the off-stream reservoir developed for Stafford County, and it will double the county's water supply. The reservoir began to fill with 5.3 billion gallons of water in 2014, after 22 years of planning and construction. The dam to create the 500-acre reservoir was constructed on Rocky Pen Run, one-half mile from its confluence with the Rappahannock River and away from sensitive riparian areas there.

proposed off-stream reservoir (Rocky Pen Run) in Stafford County - north of Rappahannock River

Source: Proposed Rocky Pen Run Reservoir Site

The water source is the Rappahannock River. The intake is two miles upstream from the confluence of Rocky Pen Run and the Rappahannock River. The reservoir was originally called Rocky Pen Reservoir, but then renamed to honor late Stafford Sheriff's Office Deputy Jason Mooney.

Pumps can deliver 40 million gallons/day at times of high flow into the reservoir, maintaining an adequate water supply despite the small watershed of Rocky Pen Run. A 30 million gallon/day water treatment plant was constructed at the reservoir so drinking water could be piped to customers in Stafford County.5

Residences on the edge of the reservoir will see water levels drop in drought years, creating mud flats. Some of those houses are outside the boundary of Stafford County's urban services area. As a result, some houses with near the reservoir will not be connected to the county water system, and will not benefit directly from the improved water supply.6

Stafford County built its own water supply system, relying upon Lake Mooney Reservoir on Rocky Pen Run

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Building an off-stream reservoir does not always minimize damage to wetlands. The proposed King William Reservoir, with a dam on Cohoke Creek and a reservoir supplied by water pumped out of the Mattaponi River, would have destroyed 400 acres of wetlands. The Corps on Engineers ultimately blocked that project.

Spotsylvania County had hoped Newport News would succeed in getting approval for the King William Reservoir, creating an precedent for dismissing wetlands impacts when approving water supply projects. Delays in approval of the Clean Water Act Section 404 permit to destroy wetlands for the Po River Reservoir finally forced Spotsylvania County to partner with Fredericksburg and create a joint water supply system.7

the Spring Hollow Reservoir, built in the mid-1990's upstream of Roanoke to provide off-stream storage, now supplies drinking water to the Western Virginia Water Authority

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Off-stream reservoirs are used to supply water for Henrico County and Roanoke County, but Loudoun County has adopted the most unusual plan for an off-stream reservoir in Virginia.

Loudoun is bisected by Goose Creek, but the City of Fairfax developed that water source in the 1950's. By the time Loudoun County had urbanized enough to justify building a water utility system, the opportunity to build a standard dam-and-reservoir had passed. Instead, the county opted to develop a water banking system, pumping water from the Potomac River during periods of high flow - but the county chose an innovative approach to creating a new off-stream reservoir.

Instead of damming a small stream and flooding 1,000 acres of land, which would cause unpopular environmental impacts and require massive expenditure for acquiring land, Loudoun County will store Potomac River water in quarries. The county has several basalt quarries that were excavated to supply gravel for roads and buildings, but are near the end of their useful lives because development nearby has blocked quarry expansion and/or the cost to move rock up to the surface is too high. Loudoun will purchase quarries as they are abandoned, and use them as reservoir sites.8

Loudoun County's off-stream reservoirs will be abandoned basalt quarries

Source: Loudoun Water, Vicinity Map

References

1. "Salem Church Dam is an undying symbol," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, February 6, 1986, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19860206&id=tOBLAAAAIBAJ&sjid=nYsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2793,1061501; "Dam's fortune's rose, fell," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, October 4, 1974, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19741004&id=O_ZNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=FIsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5401,482872 (last checked February 9, 2015)

2. "Water and Sewer Master Plan Revisions 2002 - Chapter 2, Background," Spotsylvania County, 2002, pp.5-7, http://www.spotsylvania.va.us/content/2614/147/2744/223/2084.aspx; Amit Sachan, "Safe Yield for Jointly Operated Reservoir System and Examination of ENSO Impacts," Masters thesis at Virginia Tech, 2003, p.8, http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05282003-081537/unrestricted/Final_Thesis.pdf; "Hope rises for a thirsty county," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, January 3, 1999, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19990103&id=xPAyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=oAgGAAAAIBAJ&pg=6259,508926 (last checked February 9, 2015)

3. "Mapping for reservoir underway," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, November 21, 1988, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19881121&id=s_pNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=fIsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2247,4284001; "Water and Sewer Master Plan Revisions 2002 - Chapter 3, Flow Projections," Spotsylvania County, 2002, p.29, http://www.spotsylvania.va.us/content/2614/147/2744/223/2084.aspx; Bob Hume, "Regulatory Perspective," presentation at 2007 Water Supply Planning Seminar, Virginia Section: American Water Works Association, 2007, http://www.vaawwa.org/resources/ (last checked January 20, 2015)

4. Amit Sachan, "Safe Yield for Jointly Operated Reservoir System and Examination of ENSO Impacts," Masters thesis at Virginia Tech, 2003, p.7, http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05282003-081537/unrestricted/Final_Thesis.pdf (last checked January 20, 2015)

5. "Lake Mooney Reservoir," Stafford County, http://stafford.va.us/index.aspx?NID=987' "Water finally flows in reservoir," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, January 28, 2014, http://www.fredericksburg.com/news/water-finally-flows-in-reservoir/article_edd709e6-4525-589c-951a-55381e57e82d.html; "Water Treatment Plant at Lake Mooney will get upgrades," Potomac News, December 29, 2021, https://www.potomaclocal.com/2021/12/29/water-treatment-plant-at-lake-mooney-will-get-upgrades/ (last checked December 29, 2021)

6. "Reservoir Nearly Ready for Water," Free Lance-Star, August 30th, 2013, http://www.fredericksburg.com/news/reservoir-nearly-ready-for-water/article_4441aceb-2faf-50dd-85c5-b22b597c0c3a.html; "Chapter 7 - Public Facilities Element," Spotsylvania County Comprehensive Plan, 2008, pp.37-40, http://www.spotsylvania.va.us/filestorage/2614/147/2740/169/205/2008_Comprehensive_Plan_reduced_wBookmarks_23.7_MB_(03-21-2012).pdf (last checked October 31, 2013)

7. "Mapping for reservoir underway," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, November 21, 1988, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19881121&id=s_pNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=fIsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2247,4284001; "James City County proposal called parallel to plan at Po River," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, August 7, 1992, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19920807&id=CvxNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=oIsDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2115,1076053 (last checked October 31, 2013)

8. "A safe, reliable water supply for generations," Loudoun Water, http://www.lcsa.org/Residential-Customers/Potomac-Water-Supply-Program/ (last checked November 3, 2013)

Claytor Lake Dam, which blocks the main stem of the New River, was built before environmental impacts were assessed for such projects

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Radford South 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2013)

Rivers and Watersheds of Virginia

Virginia Places