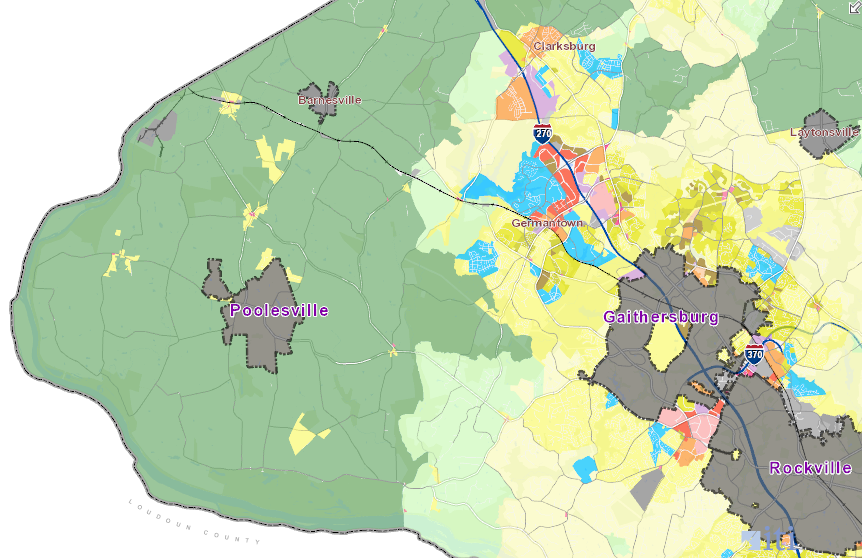

Montgomery County has planned for low-density development where Virginia officials have proposed a new road connecting the Western Transportation Corridor to I-270

Source: Montgomery County Zoning

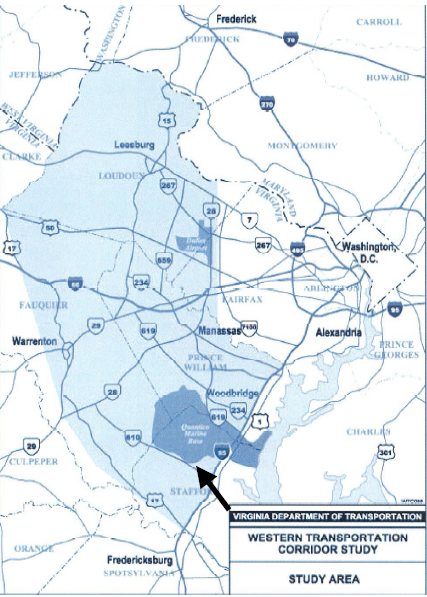

Another beltway has been proposed to affect land use as well as traffic in the outer suburbs of Spotsylvania, Stafford, Fauquier, Prince William, and Loudoun counties. The part of the proposed road west of I-95 has been known by multiple names, including Western Transportation Corridor, Tri-County Parkway, and Outer Beltway.

In some proposals, it would start at a new intersection on I-95 south of Fredericksburg and cross the Rappahannock River on a new bridge. Other versions avoid a conflict with the conservation easement on the riverbanks which prohibit such a bridge, and instead parallel Route 17 or convert it into an interstate-quality road. The new highway would then carve through western Stafford, Prince William, and perhaps Fauquier counties to Gainesville.

In Prince William County, one possible route was to expand Thoroughfare and Antioch roads west of Haymarket. The Haymarket Bypass would parallel Route 15 along Bull Run Mountain.

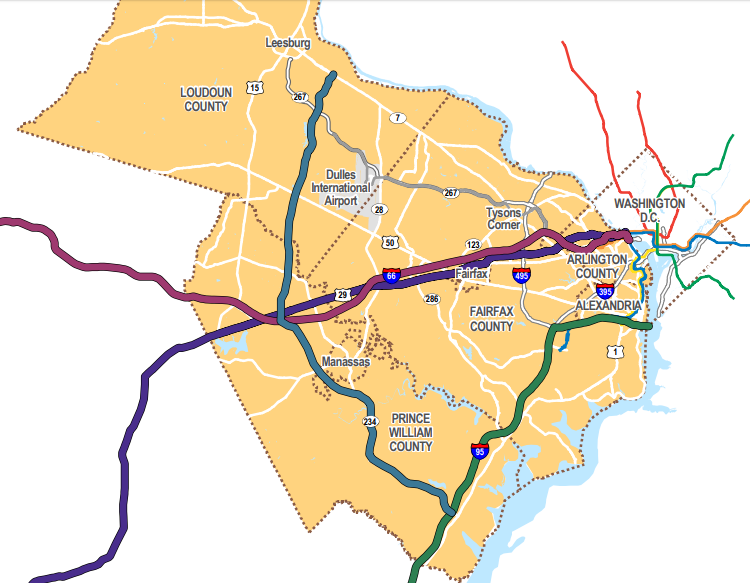

A more-likely option still being considered is to build a connector of some sort from an upgraded Route 17 to the existing Route 234 Bypass. That road now ends at I-66. In a proposal known most recently as the Bi-County Parkway, it would be extended north through western Prince William and Loudoun counties.

In Loudoun, the Bi-County Parkway would run west of Dulles International Airport (perhaps using Northstar Boulevard), crossing Route 50 and Route 7 to a proposed new bridge across the Potomac River. North of that proposed bridge, a new connector road through Montgomery County would complete the link from Fredericksurg in Virginia to I-270 in Maryland.

Maryland officials have made clear that building a new bridge and a road from the Potomac River to I-270 is not consistent with their transportation or land use planning. Montgomery County has planned and zoned the western side of the county for large-lot (25-acre minimum) development with high-value estate homes.

Snce 1980, preservation of agriculture and rural open space has been the priority. Maryland officials are not seeking, in that part of the county, the new housing developments that would be stimulated by a new transportation corridor.1

Montgomery County has planned for low-density development where Virginia officials have proposed a new road connecting the Western Transportation Corridor to I-270

Source: Montgomery County Zoning

Despite Maryland's clear policy, Virginia officials have intermittently proposed building an outer beltway of some sort, with a new Potomac River bridge and highway north to I-270. The history of the proposal stretches back almost to World War II.

The National Capital Planning Commission proposed a Cross Country Loop in 1950. The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission included an outer beltway in its 1953 master plan for highways.2

The link between the location of new roads and where new development occurs was already clear. In 1956, a discussion about the proposed Loop Highway (now the Capital Beltway, I-495) at the precursor of today's Northern Virginia Regional Commission revealed:3

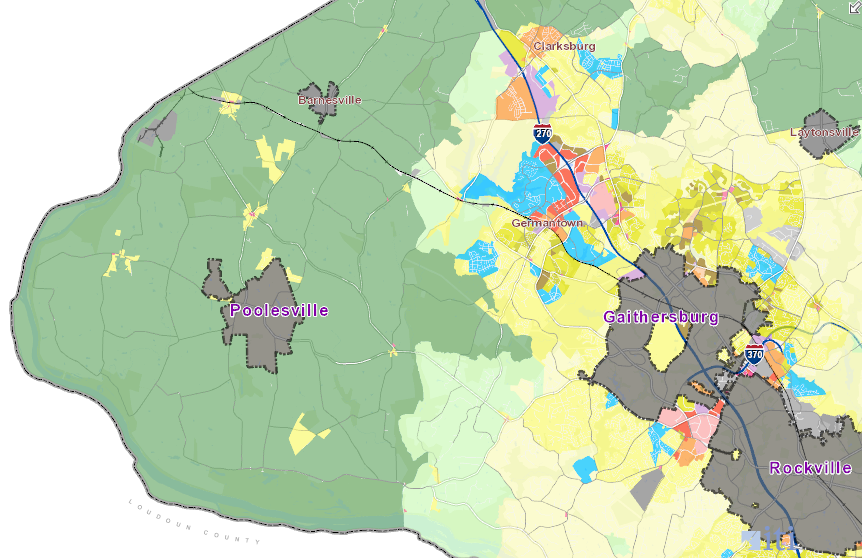

The outer beltway was retained in the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 1964 General Plan. That "Wedges and Corridors" plan proposed concentrating new housing and commercial development along defined transportation corridors, and maintaining low-density development in the wedges between the major roads.4

The 1964 plan made several key assumptions that did not become true:

- jobs would remain concentrated in the urban core around Washington DC

- local and state officials would zone land near transportation corridors with high-enough density to house the workers who would commute to jobs in the urban core

- the space between the ransportation corridors would become green wedges of parkland and low-density development

the 1964 General Plan proposed both an outer beltway and other roads, but also assumed low-density development away from transportation corridors

Source: Montgomery County Zoning

As the population of Northern Virginia swelled in the 1950's, local officials zoned most of the land between the corridors for greater housing density.

In 1956, Fairfax County sought to concentrate new development on the eastern side of the county. It rezoned the western two-thirds of the county from 0.5-acre lots to 2-acre lots, in order to concentrate new housing subdivisions closer to the jobs in the DC-area and reduce the taxes required to support that development. In the seminal 1958 Board of Supervisors vs. Carper case, a Virginia court ruled that such restrictions on development violated the state constitution. The Virginia Supreme Court endorsed that point of view in 1959.

In the 1960's amd 1970's, developers continued to win legal cases limiting the ability of local governments to shape development patterns through zoning. In 1982, Fairfax County downzoned 41,000 aces near the Occoquan Reservoir. A state Circuit Court finally endorsed the legal authority to do so in 1985, but by that time the county had lost the option of limiting housing density in the wedges between transportation corridors.5

Traffic congestion increased as local roads, in addition to the main corridors leading into the District of Columbia, were overwhelmed by increased commuter traffic. Prince William County and then Stafford County grew into "bedroom communities," and public demand to build roads to solve congestion steadily increased. In 1986, the Governor Baliles and the General Assembly increased taxes to fund transportation, providing the essential ingredient for building the Western Transportation Corridor - new money.

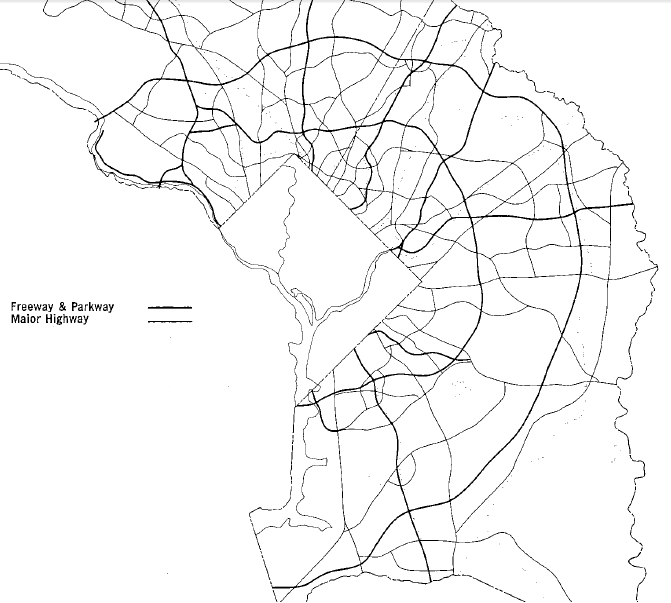

The Washington Bypass Study, First Tier Draft Environmental Impact Study, was completed in April 1990. Maryland was interested in the tw options for the eastern bypass. They could improve access to the Port of Baltimore and Baltimore-Washington International Airport and spur economic development at those sites, and a substantial percentage of trucks that used I-495 could be diverted off the Woodrow Wilson Bridge.

One option wuld have paraleled or upgraded US 301 from I-95 to the Harry Nice Bridge across the Potomac River. The other viable alternative started further north at Dumfries, and included a new across the river to Charles County.

Virginia officials had little interest in a transportation corridor on the east side of I-95, but continued to pursue two western routes that might enhance development at Dulles International Airport. One option started in Stafford County, near today's regional airport. After turning north, it passed on the west side of Dulles airport. The location of the airport runways would have limited the ability of vehicles to get to the airport terminal or shipping warehouses.

Another option started north of Dumfries, cutting west to near the county landfill. After going north towards Centreville, it would have used the Route 28 corridor and provided access to Dulles on the east side of the airport. Later, both Prince William and Fairfax counties build "parkway" north of that alternative. The Fairfax County Parkway provides a direct link between I-95 and I-66. Both county parkways serve primarily local rather than interstate traffic because of delays caused by the number of curb cuts, median crossings, and stoplights.

The eastern and western legs of the bypass did not connect to form a complete "loop highway" outside of the Capital Beltway, unless each building a common interchange near Dumfries.

Federal officials were reluctant to discuss funding any highway project that did not have clear, united support from both states, and pointed out that Federal funding for Metrorail was a higher priority.6

the 1990 Washington Bypass Study proposed two eastern and two western routes for I-95 traffic to get around Washington, DC

Source: Roads to the Future, Washington Bypass Studies

In 1997, the Virginia Department of Transportation completed a Major Investment Study to justify construction of the proposed Western Transportation Corridor. That led to an Environmental Impact Study (EIS), and the Transportation Planning Board (TPB) for the Washington metropolitan area included a study of the proposal in its 2003 Constrained Long-Range Plan (CLRP).

Due to opposition to the project, the Environmental Impact Study was terminated in 2003 before completion. The road was removed from the Fredericksburg Area Metropolitan Planning Organization's 2003 Constrained Long-Range Plan and the region's 2004 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP).

Starting in 2004, the Transportation Planning Board has declined to include even a study of the road in the region's Constrained Long-Range Plan, since funding has not been identified and political support for construction is questionable.

Despite the strong local opposition, or perhaps to bypass it, in 2004 the Virginia Department of Transportation issued a Request for Information (RFI), seeking to create a public-private partnership to build the Western Transportation Corridor. The state identified a wide swath of land through which the road could be constructed. However, no private-sector partners responded to the request.7

the Virginia Department of Transportation identified a broad area for the Western Transportation Corridor in 2004

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Request for Information - Western Transportation Corridor (Attachment A)

The low interest may have reflected the low return on investment for the Dulles Greenway, a privately-funded highway built in 1995 through eastern Loudoun County to link Leesburg to the Dulles Toll Road. Drivers complained about traffic, but were reluctant to pay a premium for faster connections even for a direct road between their houses and job sites. The Western Transportation Corridor was a bypass, and few commuters would use it daily to get their jobs.

Instead, the road was perceived as a state-funded subsidy to stimulate new development on large parcels controlled by land speculators. The new road might stimulate new "activity centers" at interchanges. If the Edge City pattern set by Tysons Corner was replicated along the Western Transportation Corridor, then land acquired by the acre could be developed and sold by the square foot, generating massive profits.

Opposition to the Western Transportation Corridor came from several directions. Local redidents who preferred the low-density communities with lots of open space had no desire to see new subdivisions planted on farms. New shopping centers with high-end grocery stores such as Wegmans would be developed in the process, but many existing residents in western Fauquier, Prince William, and Loudoun counties saw the trade-off to be excessive traffic congestion and school over-crowding.

Others objected to the fiscal impacts of the Western Transportation Corridor. The benefit-cost ratio of the road was poorly defined, but it was clear that a new road between Fredericksburg and I-270 would not address existing congestion of east-west traffic. Funding directed to the Western Transportation Corridor, or smaller segments such as the Bi-County Parkway, would reduce the resources that could be applied to expand I-95, I-66, or other roads that served more people. A new bypass might speed up travel going around the District of Columbia, but did not meet the priorities of those driving into the urban core.

In 2013, Governor McDonnell and the General Assembly passed another major tax increase to fund new transportation projects. That increase came despite complaints that the Virginia Department of Transportation was inefficient and wasteful, with projects consistently over-budget and completed after long delays. The political horsetrading by state officials, including appointees to the Commonwealth Transportation Board, had led to approval of projects that had political suport but low benefit-cost ratios.

After the Republican-controlled legislature increased taxes in 2013, thse who voted for the bill had to emphasize that extra money would be used efficiently and effectively. The Virginia Department of Transportation developed a ranking process (originally called HB2, then renamed SmartScale) to evaluate proposals with more analysis to justify investment in new infrastructure.

Smart growth advocates, including the regional Piedmont Environmental Council and the local Prince William Conservation Alliance, then partnered with low-tax advocates and mobilized in Prince William County. In 2016, the Prince William Board of County Supervisors removed the Bi-County Parkway from the county's Comprehensive Plan. That reduced the potential for construction of that piece of the Western Transportation Corridor, but did not kill the project.

The Virginia Commonwealth Transportation Board has designated the route of the Western Transportation Corridor as the North-South Corridor of Statewide Significance. That allows regional and state agencies to plan and fund the road, even if Prince William County continues to object.8

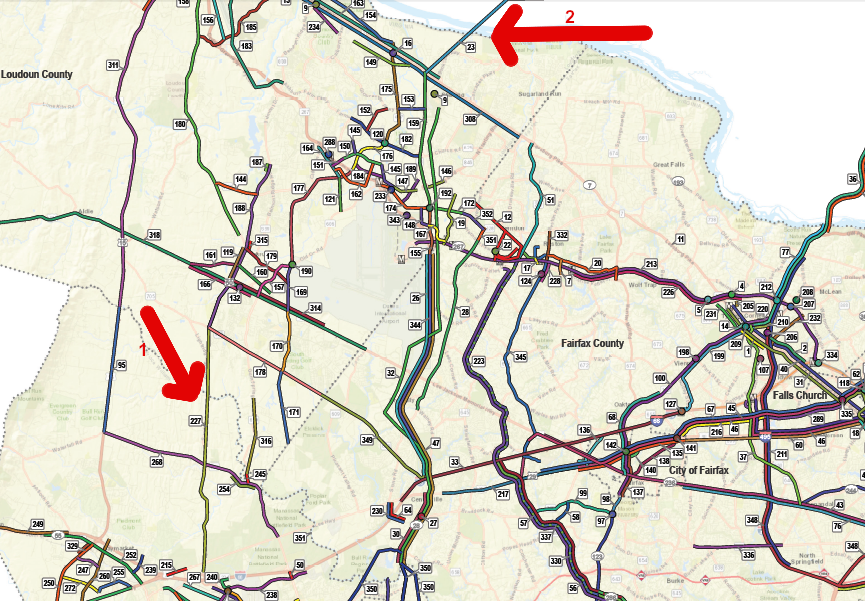

The Northern Virginia Transportation Authority has included the Bi-County Parkway and the bridge across the Potomac River in its long-range plan, TransAction.9

Loudoun County officials continue to plan for a new Potomac River bridge, and anticipate that Maryland will ultimately support it. That bridge is proposed downstream from the current Route 15 bridge, which is a change from the original "outer loop" plan of the Western Transportation Corridor.

Loudoun officials are split, and opponents argue that Maryland will never approve a new bridge and a new road up to I-70. Those who support keeping the option of a new bridge in the county's transportation plan point to the potential of Maryland changing its mind. In 2017, three Maryland officials on the Transportation Planning Board from Gaithersburg, Rockville, and Takoma Park voted to keep the bridge in the long range planning process. A Loudoun County supervisor, a supporter of the bridge, commented:10

the North-South Corridor of Statewide Significance is the blue line from I-95 to Route 7

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Northern Virginia Corridors of Statewide Significance

the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority still plans for both the Bi-County Parkway (1) and a new bridge across the Potomac River (2)

Source: Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA), TransAction