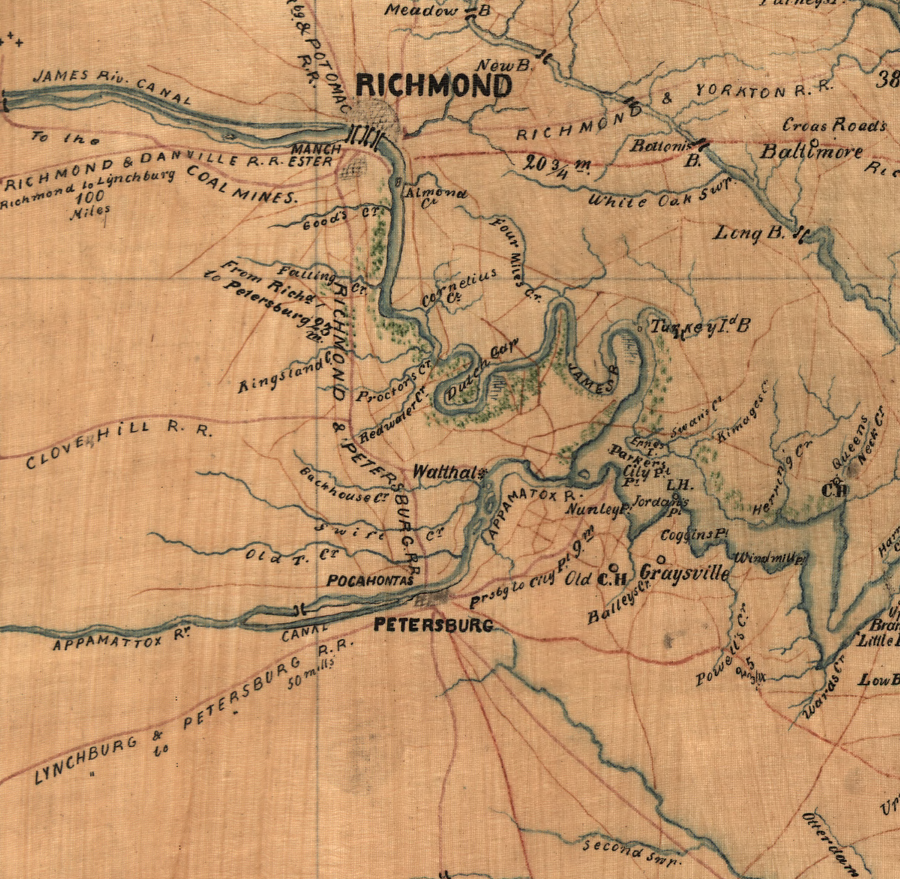

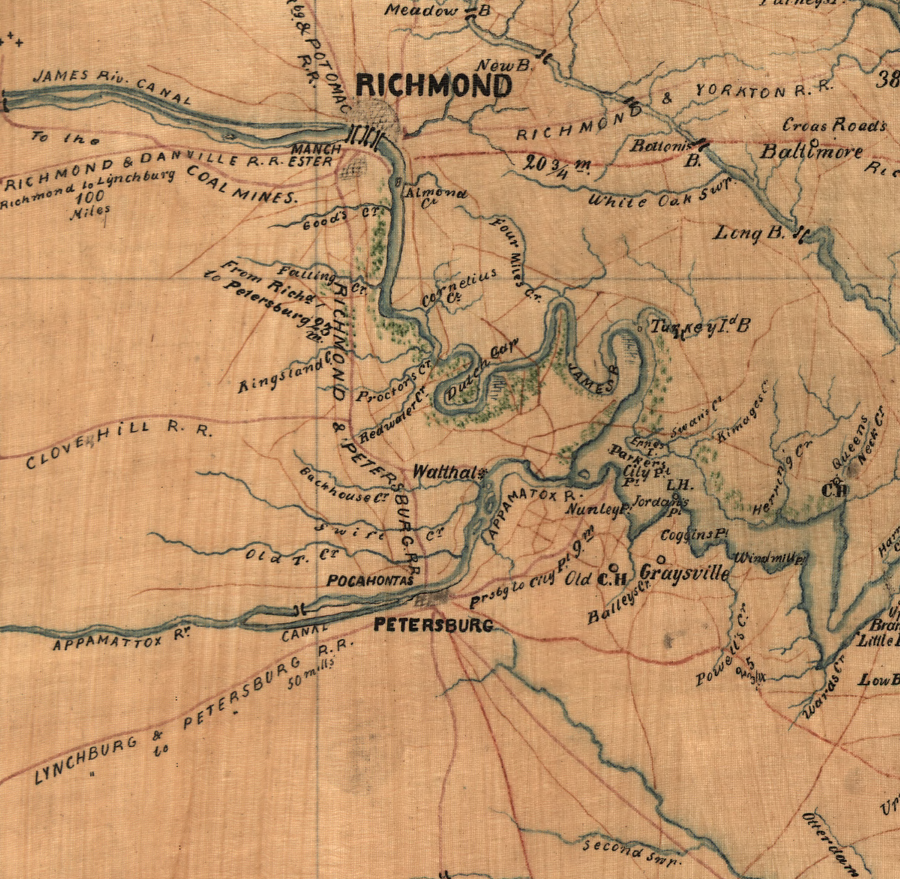

Second-Worst Decision of the State of Virginia?

Virginia borrowed money to fund transportation infrastructure, especially railroads, and struggled to pay the state debt incurred for non-profitable investments after the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, S.E. portion of Virginia and N.E. portion of N'th Carolina (by Thomas Jefferson Cram, 186_)

In the colonial era, roads were the responsibility of local residents. Plantation owners and other landowners were required by the county courts to provide labor (usually when there was a gap in demand for agricultural labor) to improve the local roads. Minimal skill was required to fill in ruts - but the House of Burgesses funded contractors to build bridges on roads that were travelled by more than local farmers. The basic theory was that local roads were a local responsibility, and regional roads were the colony's responsibility.

After the Revolutionary War, road-based trade with the other states expanded. Population growth along the Fall Line and further inland increased the demand for state support for new roads. The General Assembly funded projects on an ad hoc basis until 1816, when it created the Board of Public Works to oversee the state investments in transportation infrastructure. Before the 20th Century, Virginia did not have a state highway department. Instead of creating a bureaucracy, the state bought 40-60% of the bonds sold by a private company to finance a transportation project. The private company then hired and managed contractors to build a road, canal, or railroad.

The industrial revolution in England triggered a series of very successful canal projects to carry manufactured goods and agricultural products to markets. Virginia's Board of Public Works made a major (and unwise) commitment to canal technology. The politics of pre-Civil War Virginia required simultaneous development of canals up the James and Potomac rivers, to satisfy the large number of voters who lived in those separate watersheds. Canals on the Potomac River would benefit Alexandria and farmers in the lower Shenandoah watershed, but do nothing for voters in Richmond, Lynchburg, Charlottesville, or the upper Shenandoah watershed. In a typical political compromise, the General Assembly financed both canals.

However, the interests of those living west of the Alleghenies were largely ignored. The General Assembly financed relatively few turnpikes, canals, or railroads in the mountainous western counties. The costs per mile (and per voter) were much higher on the Appalachian Plateau. In addition, financing transportation systems that improved access to the Ohio River would nt provide any economic benefits to Fall Line seaports in eastern Virginia - Alexandria, Occoquan, Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg - or the Hampton Roads seports - Newport News, Norfolk, or Portsmouth.

That may have been logical to Tidewater politicians, but western Virginia residents considered their treatment to be grossly unfair. The Virginia state constitution was revised twice, in 1831 and 1850, in response to agitation by western representatives to have more-equal representation in the General Assembly. However, Tidewater counties continued to control the state, and eastern voters ensured that taxes on their "property" (slaves, primarily) were kept at a low level while taxes on western land and cattle were maintained at a relatively high level.

James River and Kanawha Canal at Balcony Falls

Source: A plan of James River from Lynchburg to the North Branch

(made under the direction of Thomas Moore, Principal Engineer, by Andrew Alexander and John Couty, 1820?),

from the Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works (Map #15)

The westerners felt they were required to pay excessively-high taxes for transportation improvements that benefitted the eastern region, especially the Fall Line cities of Alexandria, Richmond, and Petersburg. Those living between the Allegheny Front and the Ohio River took advantage of the Civil War to secede from Virginia and establish the independent state of West Virginia. That ensured taxes from their region would be used for transportation improvements oriented towards shipping on the Ohio River, rather than spent primarily in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

A map of the internal improvements of Virginia; prepared by C. Crozet

Source: Library of Congress (1848)

Virginia was a leader in adopting railroad technology. It built one of the first railroads in America in 1828, to haul coal from the Triassic Basin in Chesterfield to Richmond. That railroad was built before locomotives were perfected; the carts of coal were pulled on the rails by horses rather than a steam-powered locomotive.

However, Virginia made a terrible political decision in the 1830's to continue to invest in canals rather than shift to railroads. Worse, the Board of Public Works failed to examine the economic risks when it supported separate and competing projects. Virginia financed too many construction projects, and after the Little River Turnpike few of them made enough revenue to repay their investors - much less make a profit.

The effort to build a canal up the Rappahannock River failed in part because technology for construction in the 1840's was inadequate to the challenge. The engineers lacked the mathematical techniques we take for granted today, such as calculus, as well as slide rules or computers. Dynamite had not been invented yet, and hydraulic cement (which could cure and harden even when underwater) was scarce. However, the main problem was economic. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad reached the headwaters of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers before the canal. The O&A railroad provided cheap transportation to the port city at Alexandria, and there were not enough farmers in the Culpeper area producing crops for market to support both a railroad and a canal to Fredericksburg.

Virginia received prescient advice from the chief engineer for the Board of Public Works, Claudius Crozet. He recognized that railroads would be cost-effective even before locomotive technology was perfected, and that rail-based transportation could carry freight at a far lower cost per mile than canals. Crozet was forced to resign, however, and after the Panic (recession) of 1857, Virginia was headed towards bankruptcy.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the General Assembly chose to pay most of its pre-war debts rather than "readjust" them and officially declare bankruptcy. Eliminating the debt took 50 years, during which the state's schools and other services were funded at a low level. The decision to invest excessively in transportation infrastructure in the 1830's and 1840's shaped Virginia politics in both the 1800's and the 1900's.

In the 1920's, Harry Byrd rose to power, getting elected first as governor and then as a Senator. He advocated a "pay as you go" approach to funding construction of the modern highway system. In a successful political campaign just as Virginia was committing to pave roads and "get out of the mud," he set the policy that Virginia would finance road construction and maintenance from current revenues rather than borrow money through bonds.

He also designed the taxes so road costs would be paid by road users (rather than general revenue raised from income/property/sales taxes) was not abandoned by the General Assembly until 1986, when the sales tax was raised by 0.5% and that revenue dedicated to the Transportation Trust Fund. How to share the road and the load (of taxes) is a continuing debate in Virginia politics.

What has been the worst decision of the State of Virginia - so far, at least?

Using today's moral values, many people might decide quickly that the initial decisions in the mid-1600's to create an official system of slavery was the worst mistake made by the political leaders of Virginia. However, the decisions to create a legal system that supported slavery were made in the 1600's, during colonial days. The "state" or Commonwealth of Virginia did not exist until 1776. By a technicality, the decision to establish a legal system of slavery can be excluded from the contest to identify the second-worst decision of the State of Virginia.

The decision to secede from the Union in 1861 and join the Confederacy, which resulted in massive social and economic dislocation, might qualify. Tied to that decision was the establishment of legal de jure segregation after the Civil War, and the creation of Jim Crow laws that discriminated based on race with no consideration of talent or character.

"The Late Unpleasantness" led to much death and maiming on battlefields, and even greater death rate from disease in camps. Large numbers of people were dislocated, though some were enslaved people who decided that fredom was worth the challenges of moving away from known territory. The state was economically devastated. All the capital invested in buying slaves was eliminated by Emancipation. Railroads, turnpikes, and port facilities were destroyed. Farms were left without livestock or fences, and sometimes without an able-bodied man to work the fields. Three major cities, Fredericksburg, Richmond, and Petersburg, were flattened by fires and bombardments, with bridges destroyed and municipal records trashed.

Virginia's decisions to make unwise and excessively-risky investments in transportation, committing to build more turnpikes/canals/railroads than the state could afford, may be the second-worst political decision in the state's history.

The financial risk was clear, though the elected officials focused on the benefits of subsidizing transportation infrastructure that might stimulate new development in towns with enough political clout to get projects approved.

Railroads generated low (if any) profits for investors. Local business leaders in towns along the route bought stock in order to get construction started, but European and northern investors did not view individual railroads as credit-worthy investments. Railroads cost too much money to build and operate, and occasional profits had to be directed to track repair and purchase of new equipment. The probability of steady dividends for investors was low.

The state government provided the funding by purchasing stock. To finance the stock purchases, Virginia sold bonds backed by the credit of the state to European and northern investors. The process, known technically as "hypothecation," ensured that even if railroads generated no profits the state would pay dividends. If the railroads went bankrupt, the state was still committed to pay dividends.1

In 1858, as the state was committing to provide 60% of the funding to new railroads that it chartered, a state senator representing Charlotte and Mecklenburg counties warned that the commitment to new railroads was:2

- the first step towards sinking the credit of the Commonwealth beyond the hope of redemption

References

1. Scott Reynolds Nelson, Iron Confederacies: Southern Railways, Klan Violence, and Reconstruction, University of North Carolina Press, 2005, pp.20-22, https://books.google.com/books?id=vE_qCQAAQBAJ (last checked January 28, 2019)

2. Philip Stanley, "Legislating the Danville Connection, 1847-1862: Railroads and Regionalism versus Nationalism in the Confederate States of America

," Masters thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2014, pp.22-23, pp.46-47, https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4497&context=etd (last checked January 28, 2019)

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places