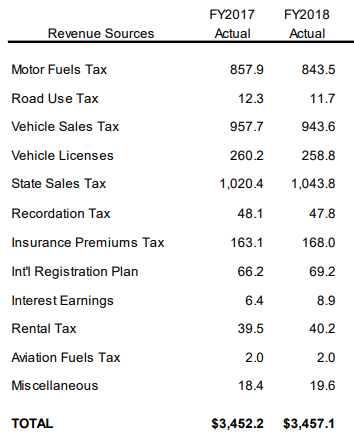

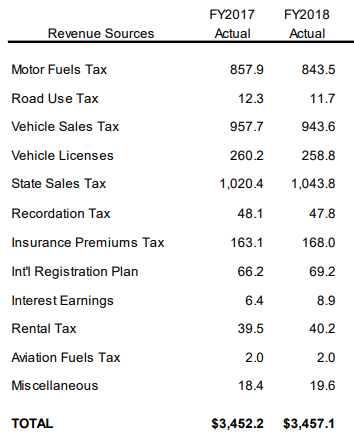

Where Does Virginia Get Funding for Transportation?

Commonwealth Transportation Fund (CTF) revenues come from multiple state tax sources, plus Federal sources

Source: Virginia General Assembly, House Appropriations Committee, Review of General Fund Revenues and the Virginia Economy for Fiscal Year 2018

Virginia first funded road construction and maintenance through the corvee system. County courts required that local residents had to work for a certain number of days each year to fill in muddy ruts, clear away brush and stumps, and ensure the roads were passable. The court appointed road overseers for different districts, and they organized road maintenance projects each year.

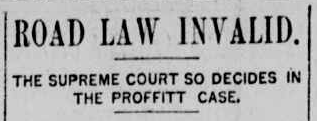

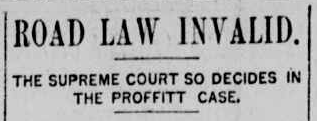

In an 1892 test case, William F. Proffitt in Louisa County objected to the demand that he contribute two days of free labor. When he refused, he was fined by the Cuckoo District road overseer. After Proffitt failed to pay and the county arrested him, he claimed his imprisonment violated the state constitution.

The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals agreed with him, in a 3-2 decision. The court ruled that the labor mandate was a poll tax, and exceeded the limits on such a tax in the Virginia constitution. In all other states except Nevada, courts upheld the labor requirement. So did the US Supreme Court, saying it did not impose "involuntary servitude" any more than the requirement to serve on a jury or in the militia.1

Virginia funded annual road maintenance by mandating unpaid labor, until the state's top court ruled in 1894 that the mandate was unconstitutional

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Richmond Dispatch (p.4, February 2, 1894)

After the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals ruled that mandating labor without compensation was not legal, the state could use convict labor, tax revenue, or both. Governor O'Ferrall, in his 1895 report to the General Assembly, called for hiring workers rather than forcing convicts to repair the roads:2

- The Supreme Court of Appeals of the State has held that road service cannot he required of the citizen, and I am glad of it, for long experience had fully demonstrated that the compulsory system was "penny-wise and pound-foolish." Our roads, then, must be worked entirely by taxation. This is settled.

The 1902 Constitution removed the prohibition of state funding for public roads, though it retained limits on all other forms of internal improvements. In 1906, it authorized use on convicts on local roads. Those guilty of "minor felonies" could be sentenced to road work rather than time to be served in the state penitentiary. The state fed, clothed, transported, and guarded the prisoners while the county furnished all equipment, materials, and a civil engineer to oversee the projects.3

The legislature began providing cash directly starting in 1908. It appropriated $250,000 for use by local jurisdictions, with the requirement that the counties had to raise matching funds.4

The Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) approves the Six-Year Improvement Program (SYIP) annually. Current funding for transportation exceeds $4 billion annually. The FY 2026–2031 SYIP allocated $18.8 billion to the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) and $7 billion to the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), for 4,500 projects.5

Links

References

1. Peter Wallenstein, Blue Laws and Black Codes: Conflict, Courts, and Change in Twentieth-Century Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2013, pp.20-25, https://books.google.com/books?id=xXI3QHGF4Q8C (last checked February 11, 2018)

2. "Journal of the House of Delegates of the State of Virginia for the Session of 1895-96," Superintendent of Public Printing, Richmond, Virginia, 1895, p.31, https://books.google.com/books?id=1xwSAAAAYAAJ (last checked February 11, 2018)

3. The Virginia Teacher, Volume 2, State Normal School for Women, July 1921, p.189, https://books.google.com/books?id=-qwpAQAAMAAJ(last checked February 11, 2018)

4. Peter Wallenstein, Blue Laws and Black Codes: Conflict, Courts, and Change in Twentieth-Century Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2013, p.28, https://books.google.com/books?id=xXI3QHGF4Q8C (last checked February 11, 2018)

5. "Six-Year Improvement Program (SYIP) Update," Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO), June 10, 2025, https://www.hrtpo.org/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=210 (last checked June 27, 2025)

Virginia Taxes

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places