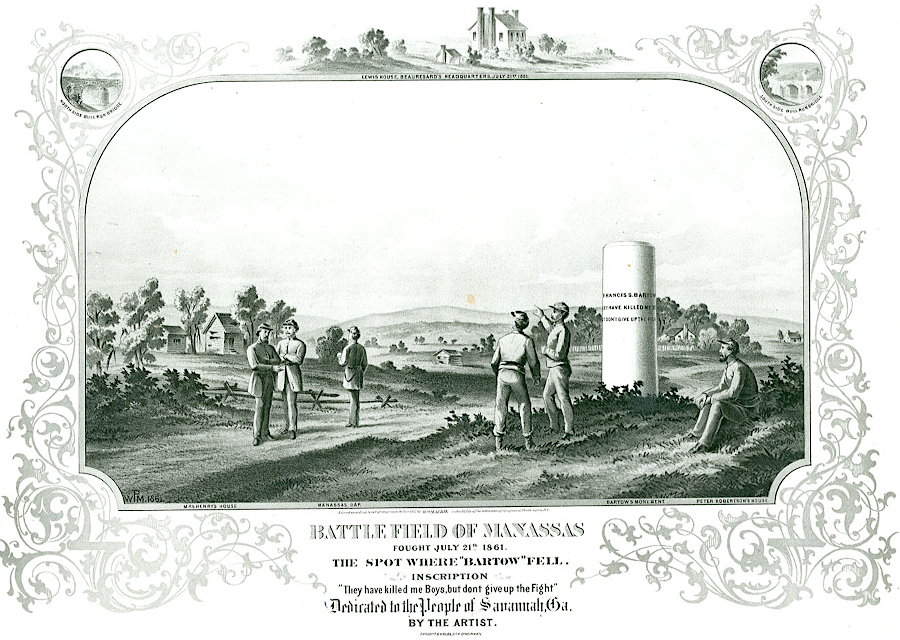

the first Confederate monument was erected to Col. Bartow, who died at the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861

Source: National Park Service, Bartow Monument

the first Confederate monument was erected to Col. Bartow, who died at the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861

Source: National Park Service, Bartow Monument

in early 1862, Union troops destroyed the marble obelisk that honored Col. Bartow - only the base remains today

Even before the Civil War ended, the first Confederate monuments in Virginia honored the soldiers and battles in which they fought. The very first Civil War monument was erected on September 4, 1861 by Confederates. The marble obelisk marked the spot where Colonel Francis S. Bartow was shot on Henry Hill at the First Battle of Manassas (known by Union soldiers as the First Battle of Bull Run). Bartow was the first officer from Georgia to die in that war.

Today just the base of the obelisk remains. Union troops gained control of the area in March, 1862 and destroyed the monument. A Pennsylvania soldier wrote in April, 1862:1

Union soldiers built monuments at Henry Hill and at Deep Cut to commemorate the First and Second Battles of Bull Run (known to Confederates as the First and Second Battles of Manassas). The two monuments were dedicated on June 11, 1865.

the monument on Henry Hill was completed in June 1865 to honor Union soldiers who fell at the First Battle of Bull Run

Source: Library of Congress, Bull Run, Virginia. Monument on battlefield; National Park Service, Bartow Monument

the Union monument erected in 1865 on Henry Hill has been restored to its original appearance, with artillery shells

Union troops dedicated the Groveton monument at Deep Cut on June 11, 1865 to honor soldiers who fought in the Second Battle of Bull Run

Source: Library of Congress, Groveton, Virginia. Monument on battlefield of Groveton

The first large celebration of Memorial Day was held at Arlington National Cemetery in 1868. That event was organized by the Union veteran organization called the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), but it was triggered as a Northern response to Southern women in Columbus, Georgia and elsewhere decorating graves of Confederate soldiers.

The New York Times observed in 1868:2

Confederate soldiers were valorized on monuments erected 50 years after the Civil War ended, such as this one at Bland County Courthouse

Within Virginia, almost all Civil War-related memorials and statues erected in the 19th and 20th centuries honored just Confederate soldiers and sailors. Statues and monuments to honor Confederates have been erected on the lawns of nearly every Virginia county and city courthouse, typically to honor "our dead" and to list the names of local units that fought in the Confederate Army. The monuments reflected the Southern effort to define the Lost Cause as a legitimate separation from the Union in which Southern men fought with honor.

"The Lost Cause" painting became an iconic image of a Confederate soldier returning to a devastated homestead, not to a plantation's mansion house

Source: Morris Museum of Art, The Lost Cause (by Henry Mosler, 1869)

In Alexandria, the Confederate memorial was placed at the intersection of Washington and Prince streets. Local units had mustered there when Union forces started to occupy Alexandria on May 24, 1861. The Confederate units fled, catching Orange and Alexandria Railroad trains to Manassas, and the city was a Union stronghold throughout the Civil War.

Starting in 1885, the R. E. Lee Camp of the United Confederate Veterans led the effort to honor the Confederates who died during the Civil War. The statue was modelled on a painting of a Confederate soldier, looking thoughtful at Appomattox on the day Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia surrendered in 1865. Inscribed on the statue were 100 names plus:3

the "Appomattox" statue stood on Washington Street in Alexandria from 1889-2020

Source: Library of Congress, Confederate Monument, Alexandria

The statue to "Stonewall" Jackson was placed on the grounds of the Virginia Capitol in 1875, but most of the monuments were installed between 1890-1920 when the veterans were aging and wanted to ensure their remembrance. The statues to Confederate leaders on Richmond's Monument Avenue were erected between 1890-1929.

When the Manassas battlefield was converted into a national park in 1940, the General Assembly appropriated $25,000 for a statue honoring General "Stonewall" Jackson. It was placed at a highly visible spot on Henry Hill, not far from where he earned his nickname at the First Battle of Manassas. Confederate veterans objected to the appearance of Jackson as "Superman" (the comic had been released just a year earlier) and the size of the horse; in reality, Little Sorrell was closer to a pony. The Virginia Fine Arts Commission refused to modify the design.

the equestrian statue of General Jackson at Manassas National Battlefield Park

When the statue of Robert E. Lee was unveiled on Monument Avenue in 1890, the Richmond Planet was the primary newspaper for the local black community. The editor, John Mitchell Jr., was also a city alderman representing the Jackson Ward. He abstained from the vote when the city appropriated funding for the statue, and wrote presciently in his newspaper:4

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) organized in 1894, four years after the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The two organizations demonstrated that women could occupy the top leadership roles in national heritage organizations, just as they did in the women's suffrage groups.

for over a century, monuments honoring the Confederacy were a feature in nearly every county seat

Source: Library of Congress, Tappahannock, Virginia

Though the United Daughters of the Confederacy maintained graveyards and maintained homes for Confederate veterans and their widows/children, a primary purpose of the organization was to espouse the "Lost Cause" perspective on the causes of the Civil War. In its interpretation of the War Between the States, the significance of slavery as the most important state's right to be retained was diminished. The organization presented other reasons to justify creation of the Confederate States of America and its defeat in 1865, and justified secession as a legal right because the US Constitution was a contract between separate states.

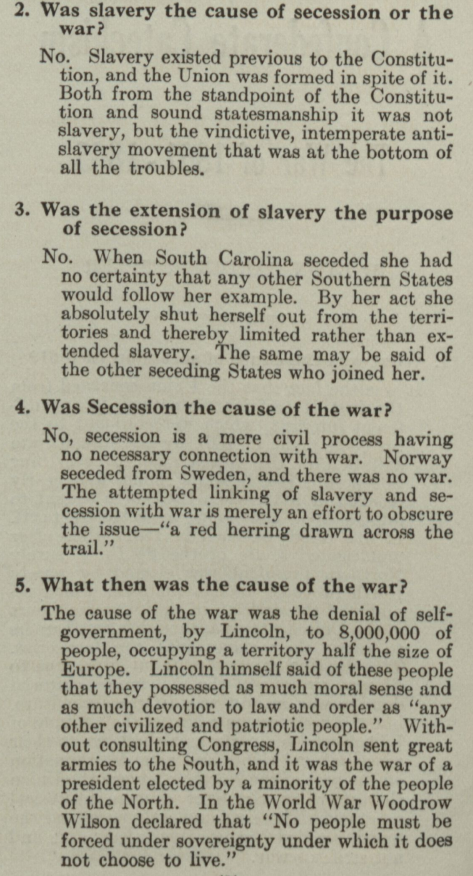

Lyon Gardiner Tyler, the son of former President John Tyler and president of William and Mary College, collected historical documentation using highly-selective criteria that matched the claims of the Lost Cause arguments. He published a Confederate Catechism in 1929 that sought to present the Confederates as equivalent to the liberty-seeking revolutionaries who led the American Revolution.5

the Lost Cause justified secession on moral grounds, separate from the desire of southern states to maintain the institution of slavery

Source: College of William and Mary, A Confederate Catechism (by Lyon Gardiner Tyler, 1929)

A statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond honoring Jefferson Davis was dedicated on June 3, 1907. The General Assembly designated Route 1 as Jefferson Davis Highway in 1922. In 1956, the United Daughters of the Confederacy financed an iron arch for a Jefferson Davis Memorial Park at Fort Monroe. The Confederate President had fled Richmond after General Robert E. Lee abandoned Petersburg in 1865, and was held at Fort Monroe for two years after he was captured in Georgia.

the Jefferson Davis monument in Richmond was a centerpiece on Monument Avenue

Source: Library of Virginia, Mercury car (April 4, 1956)

The harsh conditions of his imprisonment while awaiting trial for treason made Davis a sympathetic figure in the South, as reflected in the 1907 and 1922 memorials. The United Daughters of the Confederacy provided funding for a 50-foot high iron arch at Fort Monroe for a different reason than just to remember Jefferson Davis as Secretary of War, or even as Confederate president. In 1956, Virginia was choosing to engage in massive resistance to Federal court orders ending segregation. Honoring the Confederate past was a vehicle for expressing resistance to changing social boundaries, without mentioning racial issues directly.6

During the 1950's and 1960's, segregationists appropriated symbols of the Confederacy and portrayed them very visibly during opposition to the civil rights movement. The symbols, especially the Battle Flag, became clear representations of white resistance to integration. Later efforts to redefine them as symbols of heritage, not hate, were unsuccessful. Some groups, like the Virginia Flaggers, embraced the Battle Flag while recycling the claims in the "Confederate Catechism" that justified secession without acknowledging the role of slavery.

the Virginia Flaggers repeated the Confederate Catechism arguments in 2019

Source: Virginia Flaggers (April 30, 2019)

After the elections of President Obama and then President Trump, the close association between Confederate monuments and white nationalism spurred initiatives to move the historical statues and monuments out of public places of honor.

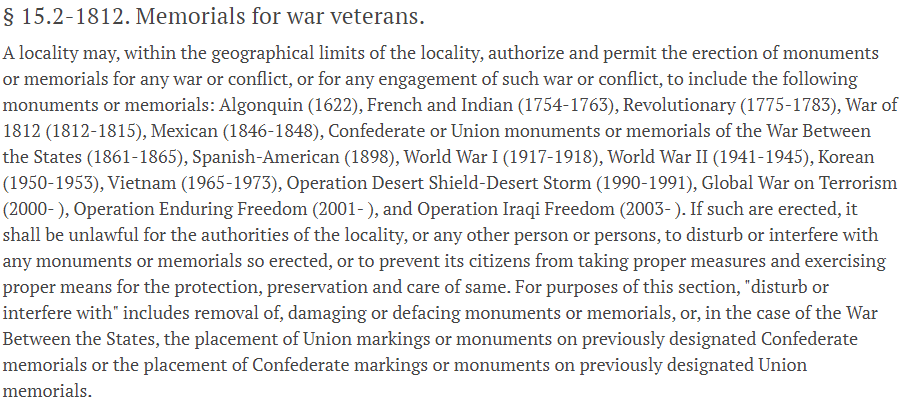

Until 2020, local governments were constrained in their ability to move Confederate war memorials. In 1904, the General Assembly first granted blanket authority for counties to construct Confederate war memorials in public squares. Prior to that law, local jurisdictions had to obtain special approval from the state legislature to erect such monuments, since Virginia is a Dillon Rule state. The law prohibited anyone from disturbing the monuments or interfering with those who might be caring for them.

The Code of Virginia was modified in 1988 to authorize construction of memorials for the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War. In 1997, the legislation was amended to grant authority to cities and towns as well as to counties to authorize construction on publicly-owned sites other than public squares, and to commemorate a broader range of past military events.7

the authority for local governments to erect, maintain, or move military monuments is defined in the Code of Virginia

Source: Code of Virginia, Section 15.2-1812. Memorials for war veterans

Those who supported relocation of Confederate monuments emphasized their association with a government that fought for preservation of slavery, plus their association with racist opponents of civil rights starting in the 1950's. Seeing symbols of racism on a regular basis ("monuments that only honor hate") is viewed as unpleasant and even oppressive, since such symbols are supported by the government.

Those who opposed relocation of Confederate monuments objected to changing traditional landscapes, places that were comfortably familiar. Others saw changes as efforts to minimize the role of famous people whose lives were considered significant.

Supporters of leaving monuments in place have also expressed concerns that moving them would be equivalent to erasing history, or rewriting it to be "politically correct" rather than accurate and complete. Some who viewed the Confederate period as a disastrous stage in Virginia's evolution were still opposed to moving the monuments to places of lower visibility, because reducing their visibility might limit opportunities for confronting all the stories of the past. In their view, it is helpful to examine the full breadth of what has happened in the past in order to reach a deep understanding and ultimately reconciliation.

Transferring monuments to historical museums, away from streets and courthouse lawns, moves items that trigger emotions as well as thoughts from daily public view. Those advocating for such changes note that in a historical setting, interpretation can tell a more-complete story of the people and events shown in the stone and bronze. In particular, signage can elaborate on how the monuments were associated with Confederate ideology that justified slavery and subjugation of people of color.

A supporter of adding more monuments to Monument Avenue in Richmond, expanding beyond the statues of Confederate leaders and Arthur Ashe, commented:8

In 2014, the Lord Bishop of London articulated the responsibility for commemorating the past on the 70th anniversary of a German V1 flying bomb destroying the Guards' Chapel at Wellington Barracks in London:9

entering the Tazewell County courthouse requires passing by a monument honoring Confederate soldiers

in East Tennessee, the statue in front of the Green County Courthouse honors the local men who enlisted in the Union army

In 2015, a white racist murdered nine African Americans in a Charleston, South Carolina church. Pictures of him surrounded by Confederate symbols led to a surge in efforts to move the monuments. In Danville, the City Council passed an ordinance on August 6, 2015 declaring that only national, state, city and MIA/POW flags would be permitted on city-owned property. That evening, a city police officer removed the Third National Flag of the Confederacy that had been flown for the last two decades at the Sutherlin Mansion, the "last capitol of the Confederacy."

The Virginia Attorney General facilitated the removal with an opinion that the flag on the grounds of the city-owned mansion was not a war monument. A lawsuit seeking to force the city to reestablish the flag at the Sutherlin Mansion reached the Virginia Supreme Court, which ruled 14 months later that the removal was legal.10

As of February 1, 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported that nationwide, 114 Confederate monuments had been moved in various states but 1,747 remained in place. Of the 262 items identified in Virginia, 14 had been moved.11

A step in the direction of "telling the whole story" occurred in Richmond when a 10-foot bronze statue of Maggie L. Walker was unveiled in July, 2017. The statue was placed in a plaza at the intersection of Adams Street and Broad Street, the gateway to Jackson Ward. That neighborhood was once the center of the black elite in Richmond, where the doctors and wealthy business leaders congregated.

The city's mayor noted that it was the first monument on city-owned property to recognize a woman. His comments also referenced how he felt about honoring a black woman and expanding the range of statues beyond those of Confederate leaders:12

On February 6, 2017, the Charlottesville City Council decided in a contentious 3-2 vote to remove the 1921 statue of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson from Jackson Park and the 1924 statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee from Lee Park. That decision was followed by a unanimous vote to rename Jackson Park as Justice Park. The city also decided to rename Lee Park as Market Street Park, and in a later vote to call that site Emancipation Park.

Gen. Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville (January, 2020)

That led to lawsuits to block the removal of the statues, plus multiple rallies to protest their planned removal. The August, 2017 Unite the Right rally made Charlottesville famous. On the evening of August 11, white nationalists carrying Tiki torches marched through the grounds (campus) of the University of Virginia chanting the Nazi slogan "blood and soil."

On August 12, counter-protestors clashed with the white nationalists at Emancipation Park and the crowd moved towards downtown Charlottesville. A speeding car driven by one of the white nationalists plowed into the counter-protestors, killing one and injuring several others. Two hours later, a State Police helicopter supporting the law enforcement response crashed outside of town, killing the two officers on board.

On August 13, President Trump famously said:13

In response, Governor Terry McAuliffe said Confederate memorials were "flashpoints for hatred, division and violence" and should be moved to museums. Senator Tim Kaine proposed removing statues of Confederate "heroes" from the US Capitol. In 1909, the General Assembly had sent a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee in uniform to the US Capitol for the first of Virginia's two slots for statues in National Statuary Hall. The second space was filled in 1934 with a statue of George Washington, three years after the state of Mississippi had used one of its two slots to install a statue of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis.14

Gen. Robert E. Lee next to Jefferson Davis, in the US Capitol

Source: Library of Congress, Statuary Hall at U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C. (1934 or 1935)

After the deaths in Charlottesville, city officials covered the Jackson and Lee monuments with black tarps and voted to sell those two statues to the highest bidder who would remove them from the parks. Six months later, a Charlottesville Circuit Court judge ruled that the tarps had to be removed while the lawsuits continued. The judge had issued a temporary injunction blocking removal of the Lee statue, but had been willing to accept a month or two of shrouds covering the monuments as an acceptable period of mourning. The statues were covered up for 188 days until he forced removal of the tarps.

The same state judge later ruled that the city could not claim the monuments were symbols of institutionalized racism rather than war memorials which were protected by state law, and issued a permanent injunction preventing the removal, disturbance, violation or encroachment of the statues. The plaintiffs who sued the city to ensure the monuments remained in place, open to public viewing, were not granted money for damages but the city was required to pay their attorneys' fees.15

In response to the planned removal of the two monuments in Charlottesville, in March 2018 the Virginia Flaggers erected a 120-foot-tall flagpole near I-64 east of the city to display the "battle flag" of the Confederacy. Other such flagpoles have been erected near interstate highways, always on private property, across the state.

the Virginia Flaggers erected a tall flagpole on private land near I-95 at Chester to display the battle flag of the Confederacy

Source: Facebook, Virginia Flaggers

Louisa County claimed the Charlottesville Spirt of Defiance I-64 Memorial Battle Flag violated the zoning there, which did not limit the flying of a Confederate flag but set a maximum height of 60' for flagpoles. A year of zoning appeals and lawsuits followed.16

In August 2017, the city councils in Norfolk and Portsmouth decided to move monuments honoring Confederates from their downtown locations to less-visible sites in city-owned cemeteries. One opponent of the proposal suggested that if the Confederate monument in Norfolk was moved, then the monument to Martin Luther King should also be taken to Elmwood Cemetery where the city maintained graves of the Confederate dead.

The Norfolk city council previously had considered moving its monument with a statue of "Johnny Reb" on top, which was erected in 1907. Discussions on moving it in 1927, 1930, and 1958 never resulted in any action, however. In 1965, the monument was placed in storage while a bank was constructed at the site. Reinstallation about 150 feet northeast of the original location was completed in 1971.

Discussions about removing that monument started again in 2015. To create a legal basis for moving Norfolk's monument, the city filed a lawsuit in 2019 claiming the state law created an unconstitutional limit to the right of free speech. The Virginia Attorney General told the court that the Norfolk statue was not protected by the 1904 state law because it applied only to counties until 1997, and when the General Assembly did not make the extension to all localities retroactive.

The Norfolk Commonwealth's Attorney and the Attorney General said in their response to the lawsuit that they would not seek to enforce the state law blocking removal, making it possible for the city to act.17

the Confederate monument on Norfolk was removed between 1965-1971, and then permanently removed in 2020

Source: Library of Congress, Main Street and Market Square [i.e. Commercial Place], Norfolk, Va. (c.1905)

In 2019, Governor Ralph Northam decided to complete his term rather than resign after his page in a college yearbook depicted a man in "blackface." The governor focused on racial equity, and encouraged removal of Confederate symbols from public places of honor.

He directed the trustees of the Fort Monroe Authority to remove the 50-foot iron arch at the entry to Jefferson Davis Memorial Park, even though it was a contributing element listed in the Fort Monroe National Historic Landmark designation. The arch was built at the time Virginia committed to massive resistance against Federal court requirements to end segregation, and it was not coincidental that the 1956 structure honored the president of the Confederate States of America.

The governor wanted swift action, before the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in English North America. The Fort Monroe Authority removed the letters on August 2, 2019, before the state-sponsored "Commemoration of the First African Landing" began on August 23. The letters were transferred to the Casemate Museum at Fort Monroe, where they could be interpreted within the context of the site's long history.18

the Jefferson Davis Memorial Arch at Fort Monroe, before removal of the letters

Source: Sarah Stierch, Jefferson Davis Memorial Park, Fort Monroe

Across the state, school boards considered adopting new names for schools that honored Confederate leaders such as Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. In 2017, after extensive debate, the Fairfax County School Board changed the name of J.E.B. Stuart High School. The community around the school proposed 73 names. Dropping the "J.E.B." to call the school "Stuart" was the first-place choice for 819 people. Coming in next were variants of Justice Thurgood Marshall or Justice, followed by Barbara Rose Johns.

The community anticipated the clear majority would determine the new name, but the popular vote was nonbinding. The School Board decided to rename J.E.B. Stuart High School as Justice High School. In Richmond, the School Board renamed J.E.B. Stuart Elementary School to Barack Obama Elementary School.19

Source: Fairfax County Public Schools, Justice HS Rededication Ceremony 2018

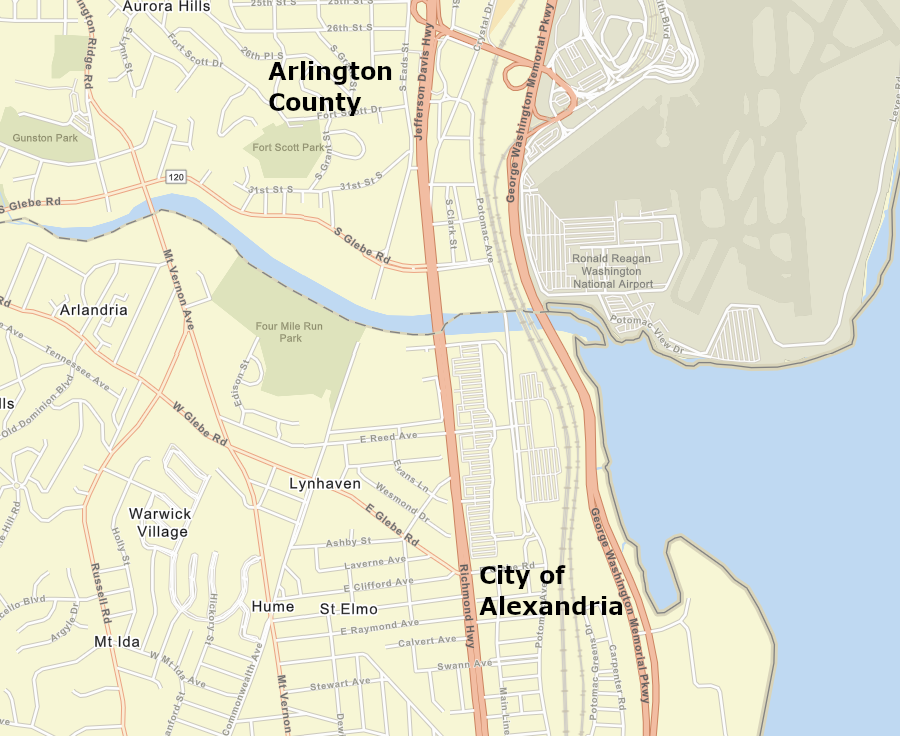

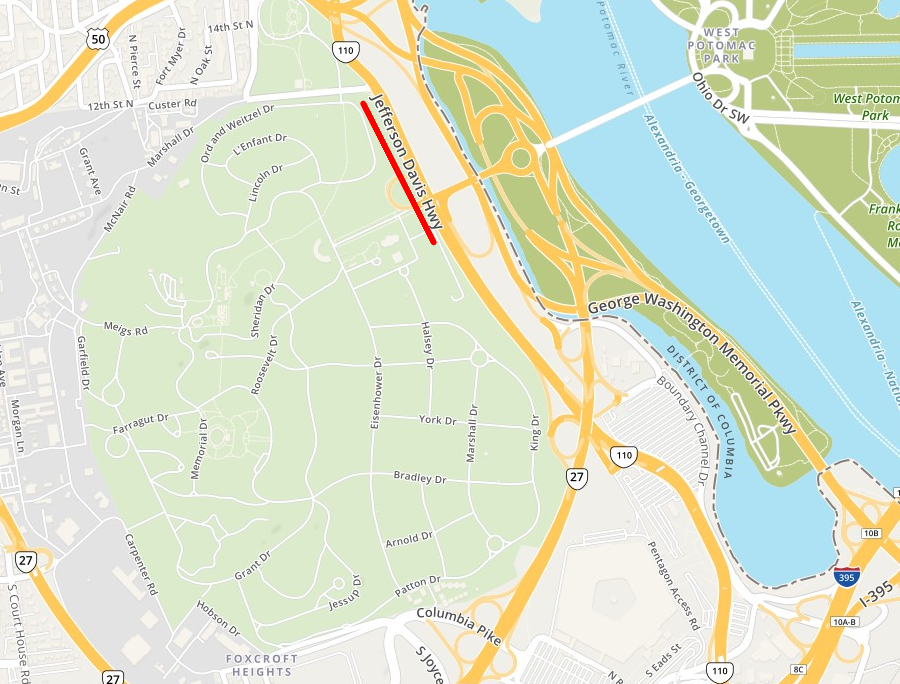

Arlington County decided in 2019 to rename a road named after the political leader of the Confederacy. All of Route 1 within Virginia had been designated Jefferson Davis Highway in 1922 by the General Assembly.

Cities had the authority to manage their roads, and within Alexandria the stretch of Route 1 was renamed Richmond Highway. The renaming process within the city involved three-year debate before new signs for "Richmond Highway" were installed at the start of 2019. Under Virginia's Dillon Rule, Arlington officials lacked the authority to name roads within the county. County officials anticipated difficulty in getting approval by the Republican-controlled General Assembly, but then the Attorney General ruled that the Commonwealth Transportation Board (appointed by the Democratic governor) had the authority to allow the name change.

Governor Ralph Northam, who was committed to addressing issues regarding race and equity and a scandal in which he was revealed to have worn "blackface" while in medical school, endorsed the change:20

between January-September 2019, Arlington and Alexandria had different names for Route 1

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Though Arlington renamed Route 1 after authorization by the Commonwealth Transportation Board, online mapping tools implemented the change on different schedules. GoogleMaps made the switch from Jefferson Davis Highway to Richmond Highway in January 2019, nine months before the change became official. In February 2020, MapQuest still labelled the road using the name of the former president of the Confederate States of America.21

MapQuest was slow in renaming Jefferson Davis Highway to Richmond Highway, within Arlington County

Source: MapQuest (as of February 23, 2020)

Arlington's supervisors also decided to rename Washington-Lee High School. The name had been used for 95 years, but after the 2019 class graduated it was called Washington-Liberty High School. That name change cost $250,000, one-third for replacing signs and the rest for "soft costs" such as uniforms.

Staunton changed the name of Robert E. Lee High School back to Staunton High School, the name used before 1914. Staunton also made the shift right after the 2019 class graduated. The school sold outdated "Robert E. Lee" athletic uniforms and gear as surplus items to the general public.22

what was once Robert E. Lee High School in Staunton was renamed in 2019

Source: Staunton High School

in August 2019, GoogleMaps still identified Staunton's high school as "Robert E. Lee High School"

Source: GoogleMaps

Not every local jurisdiction chose to alter names or monuments of Confederates. At the same time Arlington County was dropping "Lee" from the name of a high school, Frederick County decided to preserve the 1916 Confederate statue on the Loudoun Street Mall in front of the 1840 county courthouse.

Frederick County transferred ownership of the statue and the former courthouse to the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation. As part of the deal, the county and the non-government organization signed a 200-year agreement to operate a museum in the former courthouse and to preserve the statue in its existing location.23

The November 2019 elections shifted control of the General Assembly. For the first time in two decades, Democrats gained control of the House of Delegates and the State Senate. They passed legislation in 2020, 52-43 in the House of Delegates and 25-15 in the State Senate, that authorized local governments to determine the fate of Confederate monuments within their jurisdictions. Governor Northam, a fellow Democrat, signed the legislation without proposing any modifications.

The law specifically changed the relevant part of the Code of Virginia to replace "War Between the States" with "Civil War," created a commission to propose a replacement for the statue of General Robert E. Lee provided by Virginia in 1909 to Statuary Hall in the US Capitol, and established a public involvement process that granted new power to local elected officials:24

The legislation also made one exemption, to ensure no changes to the statues and plaques at the Virginia Military Institute:25

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 led to the removal of statues on public land in Richmond that honored Confederates. The most dramatic change was on Monument Avenue. The only monument left at the end of the year honored Arthur Ashe, a tennis champion and humanitarian with no direct connection to the Civil War.

Removing statues which had been in place for a century were controversial, and protestors painted many with graffiti while they were still in place. In 2020, Governor Ralph Northam was blocked by a lawsuit from implementing his plan to remove the statue of Robert E. Lee from the state-owned parcel of land along Richmond's Monument Avenue. The City of Richmond had the authority to remove statues on city-owned land, however.

The mayor acted boldly, after a difficult search to find a contractor willing to dismantle the monuments in the politically-charged environment. The first Confederate statue to be hauled away from Monument Avenue was the statue of Stonewall Jackson. On July 1, 2020, it was dismantled and moved to a storage yard at the city's wastewater treatment plant.

The governor finally obtained a court decision allowing him to move the statue of Robert E. Lee. A crane lifted it off the pedestal on September 8, 2021. The statue was then cut into two pieces so trucks could haul it to storage at the Goochland Women's Correctional Center. The pedestal was removed from the traffic circle by the end of December, leaving no trace of the monument.

The last statue honoring a Confederate on city-owned land was removed on December 12, 2022. The body of A. P. Hill was buried beneath his statue, so the legal process to authorize removal was delayed. A contractor hired by the City of Richmond disassembled the statue and hauled it to the wastewater treatment plant, while A. P. Hill's remains were taken to a cemetery in Culpeper County.

Eliminating the monument also eliminated a traffic headache on Hermitage Road; vehicles no longer had to swerve while traveling around the statue. The number of vehicle crashes at the intersection of Laburnum and Hermitage quickly dropped 71%.

The open space where the monument had stood encouraged driving through the intersection at a high rate of speed. Drivers also continued to make left turns despite restrictions during certain hours. As a solution, Richmond officials planned a roundabout. To test the response, the city first installed flex posts as a temporary measure. As one nearby resident noted:26

Source: WTVR, The statue is gone. Now Richmond wants your input on the future of this Northside intersection

The 2021 National Defense Authorization Act required the Secretary of Defense to:27

the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery was installed in 1914

Source: Arlington National Cemetery, Phase II Intensive-Level Survey of the Confederate Memorial (000-1235) (Figure 12)

Following that mandate, the Defense Department decided to remove by the end of 2024 key portions of a memorial to Confederate soldiers which had been erected in Arlington Cemetery in 1914. In 1900 President William McKinley ordered that the remains of Confederate soldiers scattered around Washington DC could be reburied in Arlington cemetery. President McKinley wanted to recognize how Southern men had volunteered to fight for the army of the United States in the 1898 Spanish-American War.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy raised money for the Confederate Memorial starting in 1906. It was designed by Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute who had fought for the Confederates at the 1864 Battle of New Market.

Inscriptions on the monument included "To Our Dead Heroes" and:28

inscriptions on the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery

Source: Arlington National Cemetery, Phase II Intensive-Level Survey of the Confederate Memorial (000-1235) (Figures 12 and 25)

The Defense Department proposed to remove the statue and the inscriptions, but leave the bare granite base intact:29

the Defense Department proposed removing all bronze elements but leaving the granite base of the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery

Source: Arlington National Cemetery, Phase II Intensive-Level Survey of the Confederate Memorial (000-1235) (Figure 19)

Former US Senator Jim Webb, who had represented Virginia between 2007-2013, objected to the removal. He wrote in a Wall Street Journal article:30

A rejoinder to Webb noted that there was opposition in both the North and the South to burial of Confederates in their own section at Arlington. The Ladies Hollywood Association in Richmond and the Ladies Memorial Association of North Carolina removed Confederate dead to gravesites in the South, the "native soil" of the soldiers.

Burying Confederates at Arlington National Cemetery facilitated reunion of the states and a more-powerful United States as it emerged as an international power, but did not create a reconciliation of Northern and Southern cultures. The Confederate Memorial was not a unifying component leading to reconciliation. Instead, it provided a focal point for honoring the distinctly different Southern society, based on legally-enforced segregation of the races and reinforced by the myth of the Lost Cause.31

The Confederate Memorial was removed on December 20, 2023. However, the Secretary of Defense in the second Trump Administration announced in August 2025 that it would be reinstalled. That was expected to take two years and cost $10 million.32

The issue of Confederate symbols was raised in 2024 when a Democratic candidate for the US House of Representatives posed with a Virginia state flag which had been adopted on April 30, 1861. That was the first time the legislature had officially adopted a flag for the state, but a similar version had been used informally since the 1830's.

The flag incorporated the state seal adopted in 1776 after Virginia had declared independence, with a woman representing Roman virtue placing her foot on Tyranny. The 1861 image put her in a suit of armor rather than with an exposed breast. The modern state flag adopted in 1950

The candidate in 2024 was unaware of the timing of the flag's adoption, or of its tenuous relationship with the Confederacy. He immediately requested that his supporter delete the Facebook post with the flag picture, to avoid any association with what he called "the brutal, dehumanizing past of this commonwealth."

The former president of the North American Vexillological Association said:33

the 1861 state flag (left), compared to the current state flag

Source: Wikipedia, 1863 Virginia gubernatorial elections and Flag and seal of Virginia

In 2022, there were still 2,089 Confederate memorials in the United States.34

At the start of his second term, President Trump sought to restore Confederate memorials as well as eliminate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs. The Department of Defense renamed military bases after little-known individuals who had the same name as Confederate generals. Fort Bragg, which had been renamed Fort Liberty, was renamed Fort Bragg again in February 2025 - supposedly in honor of Army Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, rather than General Braxton Bragg. That was followed by the decision to reinstall the Confederate monument in Arlington National Cemetery.

President Trump also issued an executive order, titled "Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History" directing the Secretary of the Interior to reinstate the pre-existing monuments, memorials, statues, markers, or similar properties which had been "been removed or changed to perpetuate a false reconstruction of American history. The order included:35

Governor Youngkin vetoed HB1699, which would have eliminated tax exempt status for personal and real property taxes paid to local governments by the Virginia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; the General Organization of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; the Confederate Memorial Literary Society; the Stonewall Jackson Memorial, Incorporated; the Virginia Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans; and the J.E.B. Stuart Birthplace Preservation Trust, Inc.. Youngkin acknowledged in his veto messages that the property tax exemptions approved by the state legislature were "ripe for reform" but stated:36

Limiting tax benefits based on the political perspective of an organization might violate the First Amendment. Governor Youngkin called for a broader reform of the process, and empowering local governments to determine whether to exempt non-profit organizations from local taxes. A law professor noted that the US Supreme Court has ruled that an attempt to limit benefits in California for a person unwilling to sign a loyalty pledge during the anti-Communist fervor in the 1950's was not legitimate:37

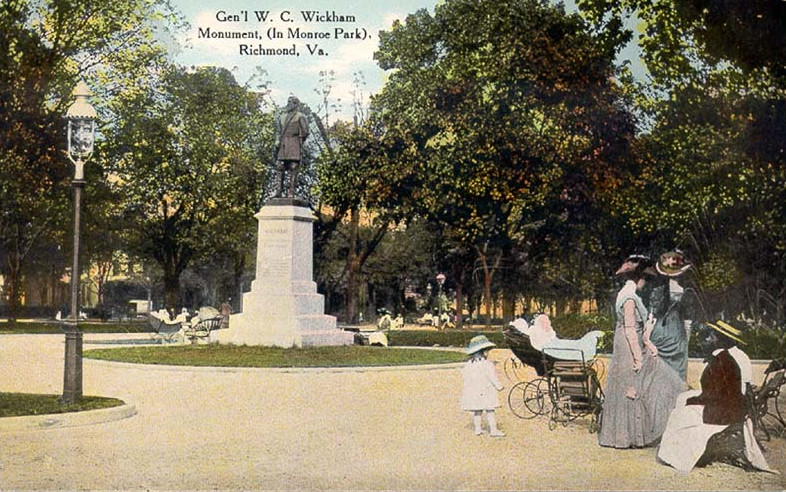

Black Lives Matter protestors started the monument removal process in Richmond on the night of June 6, 2020, when they pulled over the statue of Williams Carter Wickham in Monroe Park. Wickham had voted against secession in 1861, but ended up serving in the Confederate army as a brigadier general. The plaque on the pedestal of his statue, which was installed in 1907, said "Presented to the city of Richmond by comrades in the Confederate army."

Wickham's great-great-grandsons had requested the statue be removed, in their personal response to the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. The Monroe Park Conservancy had endorsed removal and the Monument Avenue Commission had explored that option, but city officials lacked the legal authority to act before a new state law took effect on July 1.

in 2020, protestors pulled down the statue to General Williams Wickham in Monroe Park

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), Gen'l W.C. Wickham Monument (In Monroe Park), Richmond, Va.

The next statue to fall was honored Christopher Columbus; it was pulled down on June 9. Like the statue of Wickham and unlike the statues on Monument Avenue, the Columbus statue was low to the ground and easy to place ropes on it. Richmond had already chosen to stop closing city offices on the Columbus Day holiday and to rename it "Indigenous Peoples' Day," and the statue of Columbus had been spray painted with graffiti in recent years.

The statue was tossed into a nearby lake in Byrd Park. It was later repaired, in part by the sculptor who had created the Arthur Ashe statue on Monumemt Avenue. In 2022, the city gave the statue to the Italian American Cultural Association of Virginia.

That group struggled to find a home for Christopher Columbus. No Virginia museum would accept it, though they were willing to take statues of Confederates that had been torn down. In 2024 the restored statue was put back on public display at the Rockland Lodge of the Sons of Italy in Blauvelt, New York.

When the Columbus statue was originally created, Italians in Richmond had hoped to place it on Monument Avenue. The Ku Klux Klan objected in part because Columbus was a Catholic, so the statue ended up being placed on the Boulevard in Byrd Park. As noted by a member of the Italian American Cultural Association in Richmond:38

the statue of Christpher Columbus in Byrd Park was torn down in 2020

Source: Wikipedia, List of monuments and memorials removed during the George Floyd protests (by Smash the Iron Cage)

Included in the Confederate monument removal process in 2020 was the Richmond Howitzers Monument at Park Avenue and Harrison Street. The statue, unveiled on December 13, 1892, showed an artilleryman standing at the front of a cannon with the tool used to shove the cartridges down the barrel. The sculptor had become a member of the Richmond Howitzers artillery unit in 1861.

The unit was reorganized for service in World War I and World War II, during which it participated in the Normandy invasion. At the time protestors pulled the statue down on June 16, 2020, the unit was officially Battery A, 111th Field Artillery Regiment in the Virginia National Guard39

The Virginia First Regiment Monument, erected in 1930 in Meadow Park between Park and Stuart Avenue near Monument Avenue, was pulled down from the pedestal on the night of June 19, 2020. The pedestal was removed by the city later. That monument honored the Virginia soldiers who fought in the French and Indian War, and six subsequent wars - including World War I.

Plaques on the monument referenced the regiment's service in the Civil War:40

All but one of the monuments and pedestals removed from city property in Richmond have been stored out of sight at the wastewater treatment plant. Richmond gifted the statue of Christopher Columbus to the local Italian American Cultural Association of Virginia, which repaired the damage and arranged for it to go back on public display in New York.

The statue of Jefferson Davis is the only Confederate monument that was once on city land and has been put on local display. It was incorporated into an exhibit at the Valentine Museum.

The Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and the Brick gallery organized an exhibit in 2025 to display the remnants of Confederate monuments. Decommissioned statues were mixed in with new and borrowed artworks in a unique context, transformed from the original setting of generals and political leaders on city streets and parks. Some of the monuments were shown in an unmarred condition, while others (such as the statue of Jefferson Davis) had been vandalized and covered with graffiti.

The Valentine Museum agreed to loan the Jefferson Davis statue. The Black History Museum in Jackson Ward also agreed to send to Los Angeles the "Vindicatrix" sculpture that was once at the top of the Davis monument.

The Matthew Fontaine Maury statue and globe, granite slabs from the former bases of Confederate monuments in Richmond, and bronze ingots from the statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville were loaned for the Los Angeles exhibit. That statue had been donated to the nonprofit Jefferson School African American Heritage Center in the city for its Swords Into Plowshares project. The original bronze statue of General Lee was melted down in 2023; the ingots were destined to be used to create a new work of art.

Also in the exhibit was the reworked statue of Stonewall Jackson that had been cast originally in 1921. Charlottesville removed that statue from a city park a century later, after four years of controversy. The city donated it to LAXART, a nonprofit gallery later renamed the Brick. LAXART paid the city $50,000 for moving costs and trucked the statue to a warehouse in New Jersey just before Virginia's Democratic governor, Ralph Northam, finished his term of office and Republican Glenn Youngkin replaced him.

The gallery commissioned Kara Walker to convert General Jackson's statue into a new design. She cut the statue into parts and reassembled the five tons of bronxe into a 13-foot high jumble in which Stonewall Jackson’s head is merged with the muzzle of the horse. As described by the New York Times:41

Botetourt County moved its Confederate monument from the grounds of the county courthouse in 2025. The move was not based on revising the perspective of history; instead, a new courthouse was being constructed. That 1904 monument had an inscription with a rare acknowledgement of women and Reconstruction, rather than just the men who served in military units:42

the monument to A. P. Hill was a traffic hazard on Hermitage Road in Richmond between 1891-2022

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, Gen. A.P. Hill Monument, Richmond, Va.

a Confederate soldier's dog was the first to mark the site of his death, in the 1864 Battle of Winchester

Source: Archive.org, Frank Leslie's illustrated history of the Civil War (p.446)

the myth of the Lost Cause defined Robert E. Lee, commander of a defeated army, as America's greatest general

Source: Library of Congress, Gen. Robt. E. Lee at Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862 (by Henry Alexander Ogden, c.1900)

the wife of General Pickett was instrumental in incorporating his memory in the myth of the Lost Cause

Source: Library of Congress, Gen. Pickett taking the order to charge from Gen. Longstreet, Gettysburg, July 3, 1864 (by Henry Alexander Ogden, c.1900)

the Town of Remington removed the Confederate flag from the town seal in 2020

Source: Town of Remington

Southern women feared desecration of graves of any Confederates buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Source: Chronicling America, Library of Congress, Evening Star (May 1, 1901)

the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Libby Hill overlooked the James River between May 30, 1894-July 8, 2021

Source: New York Public Library, Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Libby Hill, Richmond, Va.

site of the former Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument in 2022

in 1909 Virginia provided a statue of General Robert E. Lee, to accompany George Washington as the two people the state chose to honor in Statuary Hall of the US Capitol

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Robert E. Lee

one person was injured in 2020 when protesters beheaded a statue at the Confederate monument at the corner of High Street and Court Street in Portsmouth

Source: Library of Congress, Confederate memorial. Portsmouth, Virginia