skyline of Richmond, reflected in windows of Virginia War Memorial behind 23' tall marble statue "Memory"

skyline of Richmond, reflected in windows of Virginia War Memorial behind 23' tall marble statue "Memory"Source: Jos1etheDog, Flickr

skyline of Richmond, reflected in windows of Virginia War Memorial behind 23' tall marble statue "Memory"

skyline of Richmond, reflected in windows of Virginia War Memorial behind 23' tall marble statue "Memory"

Source: Jos1etheDog, Flickr

The Virginia focus on history and heritage includes honoring soldiers and sailors who have fought in various wars. However, the concept of marking places where battles were fought was not brought to Virginia by European colonists.

Native Americans memorialized key military events in songs and with markings on bows and arrows. A third process was to pile stones on battlefields.

John Lederer, who explored into the Monacan homeland beyond the western edge of settlement in 1669-1670, wrote:1

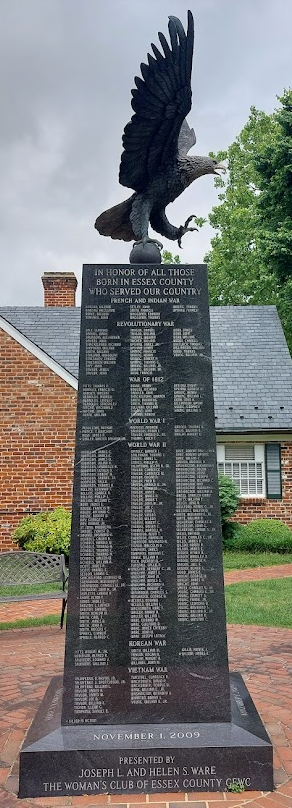

war memorial next to the Essex County courthouse

The decisions on who to honor, and who to omit, reflect attitudes of those with political power of the time that monuments and memorials were erected.

The veneration of Confederates after the Civil War peaked as that generation as dying after 1890, and as Jim Crow laws established legal segregation. Within the African-American community, the erection of monuments was controversial. Within the newspapers at the time, those objections were rarely noted outside of the press focused on a black audience.

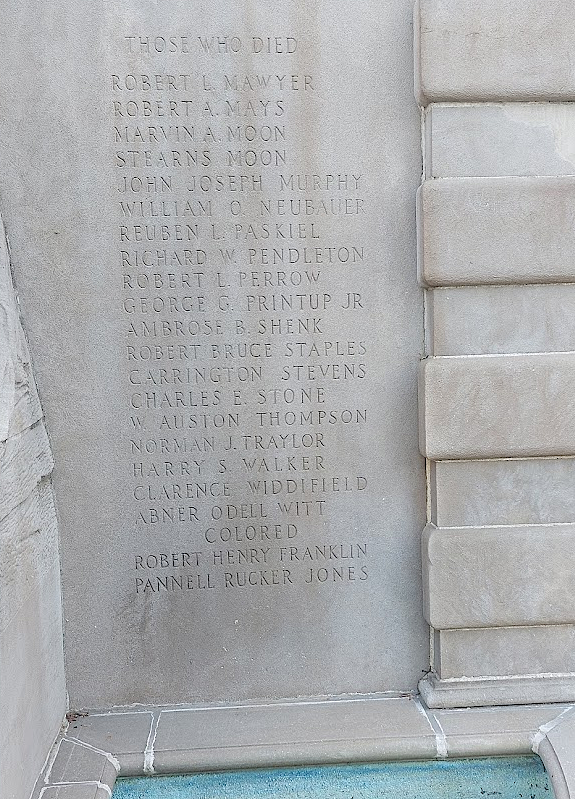

Segregationist attitudes were dominant when World War I memorials were placed on courthouse grounds. For example, the three African-American men from Loudoun County who gave the "last full measure" were included on the World War I memorial plaque in 1921, but not listed alphabetically. Their names were separated from the white soldiers, and placed at the bottom.

In 2020, after a period of national racial re-examination following the death of George Floyd while in policy custody, the American Legion supported revising the plaque. Loudoun County agreed that the War Memorial Trust Fund could be used to replace the plaque with one listing soldiers alphabetically.2

the memorial plaque on Loudoun County courthouse grounds segregated the names of the three African-American soldiers who died in World War I (photographed August, 2020)

the memorial plaque on Loudoun County courthouse grounds segregated the names of the three African-American soldiers who died in World War I (photographed August, 2020)

The Virginia Department of Veterans Services is responsible for the Virginia War Memorial, designed to honor all Virginia veterans of all wars. The memorial is located on a bluff overlooking the James River in Richmond.

It was initially opened in 1956, to honor those who served - and especially those who died - in World War II and Korea. A $26 million expansion began in 2017, to provide space for the names and stories of veterans involved in the Global War on Terror.3

Other memorials commemorate the many military conflicts which occurred within Virginia, and those outside the state boundaries in which Virginians were involved.

Less than two weeks after the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, the Confederation Congress passed a resolution to permanently mark the event:4

In 1834, 53 years later, the Yorktown residents petitioned the US Congress to construct the monument. They tried again in 1836. Fredericksburg and Boston requested support for American Revolution memorials in 1876, but the Federal government prioritized completion of the Washington Monument first.

The 100th anniversary of the Yorktown battle was the trigger for action. The US Congress authorized and funded the Yorktown Centennial Celebration and the monument in 1880. The cornerstone was laid in 1881 and the Yorktown Victory Monument was completed in 1884. The monument was constructed on four original Yorktown lots, numbered 80-83.

In 1942, the "Liberty" figure at the top of the column was struck by lightning. A new statue was placed on the column in 1956. Though lightning rods were added at that time, the hands and torso were damaged by another lightning strike in 1990. The lightning protection was upgraded when that damage was repaired.5

War memorials include more than statues.

At Jamestown, the National Park Service and Preservation Virginia have reconstructed portions of the walls at the site of the original fort which played such an important role in the first Anglo-Powhatan War (1609-13). The Commonwealth of Virginia, through the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, built a replica of the fort in 1957 for the 350th anniversary of English colonization.

The two sites tell the stories of both the original Virginia residents led by Wahunsunacock (Powhatan) and the English colonists led by a series of Council Presidents (including John Smith) and then governors appointed by the Virginia Company. Nearby, the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation manages the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown.

the Confederation Congress authorized the Yorktown Victory Monument in 1781, but the cornerstone was not laid until 1881

the Confederation Congress authorized the Yorktown Victory Monument in 1781, but the cornerstone was not laid until 1881

Source: Library of Congress, Yorktown Monument (Alliance and Victory Monument), Yorktown, Virginia. Rendering (1884)

Almost every courthouse in Virginia has a statue nearby commemorating the soldiers who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Until 2021, all but one of the statues along Monument Avenue in Richmond honor Confederate leaders. The city removed those Confederate memorials, and in 2021 the state removed the Lee statue from its pedastal.6

A debate about moving statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson in Charlottesville brought white nationalists to that city for a Unite the Right rally in August, 2017. The event brought national attention to the city after a counter-protester was killed, along with two state policemen in a helicopter crash. That event intensified debates within multiple Virginia jurisdictions about the pros and cons of relocating monuments related to the Confederacy, and led to the removal of Confederate statues from courthouse lawns in multiple jurisdictions.7

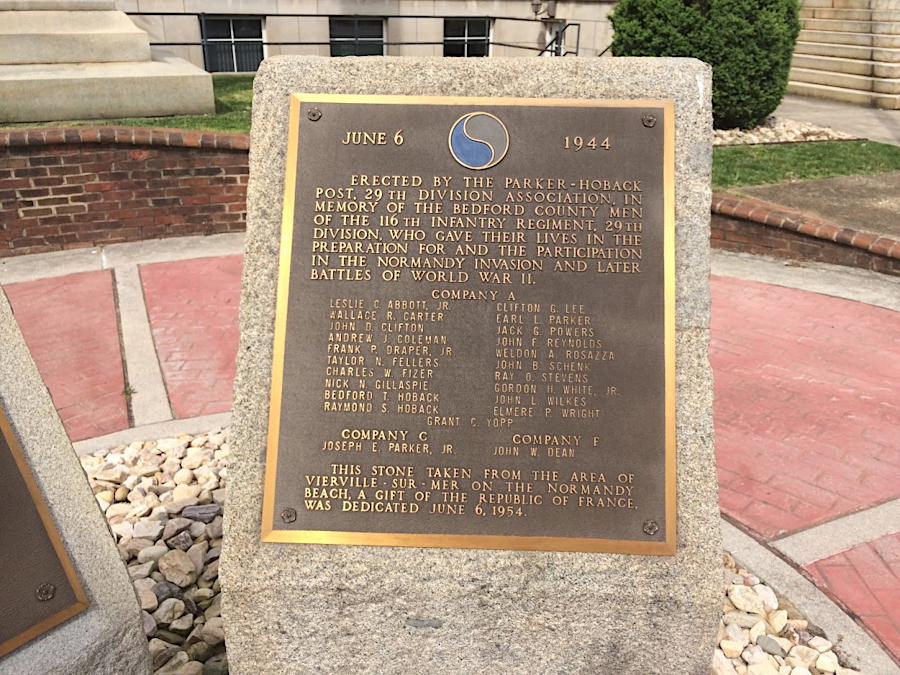

a plaque at the Bedford County Courthouse honors the soldiers from Bedford who died on D-Day (June 6, 1944)

the "Doughboy" statue in Lynchburg still segregates the World War I dead by color

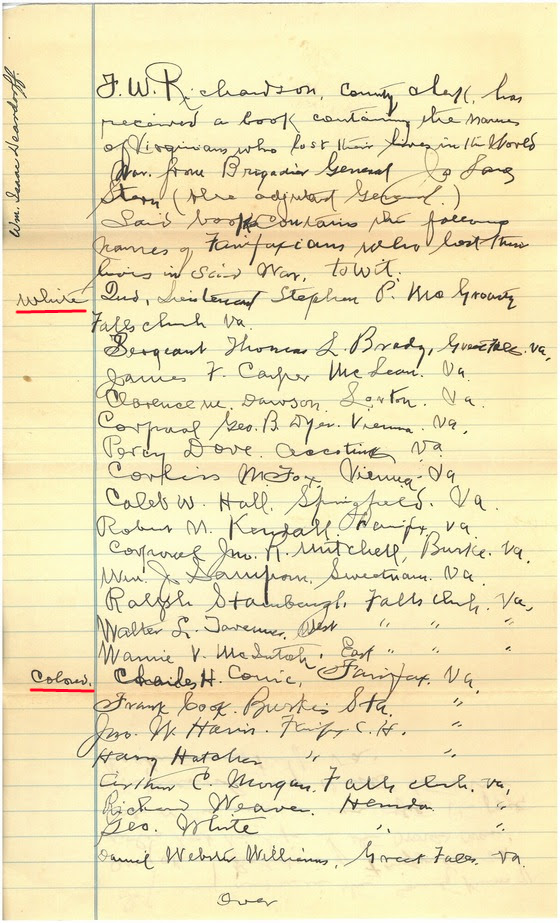

the Clerk of the Court in Fairfax County listed soldiers who died in World War I by race, and the World War I Memorial at the courthouse placed the 10 "colored" soldiers at the bottom rather than alphabetically

the Clerk of the Court in Fairfax County listed soldiers who died in World War I by race, and the World War I Memorial at the courthouse placed the 10 "colored" soldiers at the bottom rather than alphabetically

Source: Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, Found in the Archives newsletter (May 2025)