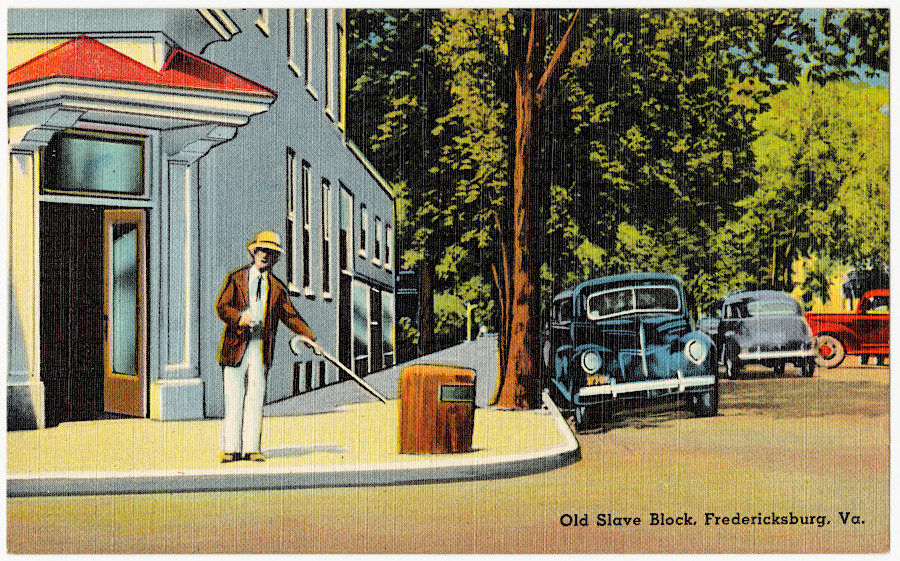

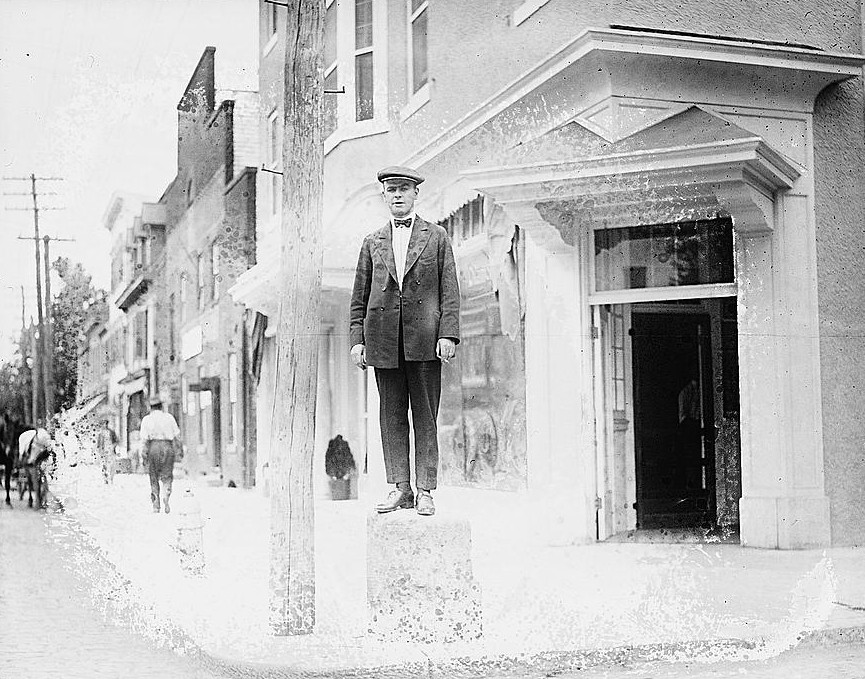

tourist postcards highlighted the slave sale site in Fredericksburg

Source: Boston Public Library, Old Slave Block, Fredericksburg, Va. (ca. 1930-1945)

tourist postcards highlighted the slave sale site in Fredericksburg

Source: Boston Public Library, Old Slave Block, Fredericksburg, Va. (ca. 1930-1945)

At the corner of William and Charles streets in Fredericksburg, a sandstone block was placed originally outside the United States Hotel. That hotel was built in 1843; when sold to a new owner in 1851, the hotel name was changed to the Planter's Hotel. The stone was a carriage step that enabled people to get in and out of horse-drawn carriages, but its other use is why the stone has historical significance.

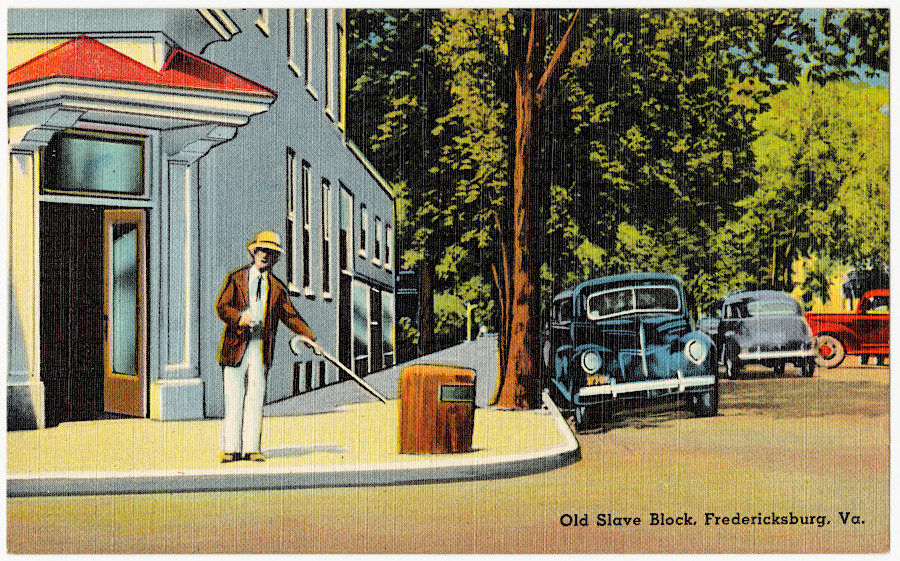

In Fredericksburg, sales of enslaved men, women, and children were held in front of the hotel. According to eyewitness reports and local tradition, people were placed on the "slave rock" to provide potential buyers a better view, with the last sale in 1862. A 1908 history of Fredericksburg stated:1

enslaved people were sold in front of the hotel once located next to the stone

Source: Boston Public Library, The Slave Auction Block at William and Charles (from Richmond Whig, December 24, 1847)

In 1913, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities requested the city place a marker at the site because it was historic. In 1924, the chamber of commerce proposed removing the slave block because it was a deterrent to tourism, and claimed the stone was just a carriage step and never used for slave auctions. A vigorous local response disputed that claim, and the stone was not removed.2

Starting in 1984, a plaque at the site provided a small part of the context via the words "AUCTION BLOCK, Fredericksburg's Principal Auction Site in Pre-Civil War Days for Slaves and Property."

Vandals damaged the slave block in 2005, smashing chunks of sandstone from the top with a hammer. The city repaired the damaged stone. A local guide who led black history tours in Fredericksburg described the significance of the slave block to residents and visitors:3

the slave block was located at the corner of Charles and William streets

Source: City of Fredericksburg, Slave Auction Block

In 2017, after a counter-protestor was killed at the white nationalist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, the city started another community dialogue on how to deal with the relic of slavery within the city's vision statement of "Sharing Our Past, Embracing the Future." One of the city's responses to Frequently Asked Questions about the slave block addressed directly the benefit of keeping it in place vs. moving a painful reminder of the past to the nearby Fredericksburg Area Museum:4

The community dialogue did not produce a consensus. City Council decided in June, 2019 to relocate the block to the Fredericksburg Area Museum.5

The local newspaper, in an editorial in support of leaving the block in place, made clear how the reminder of slavery compared to other monuments in the area commemorating the Civil War:6

Even after the decision by the City Council, the Architectural Review Board was unable to concur. The group split on a motion for a certificate of appropriateness for the change in the city's Historic District, and ended up making no decision before the 90-day window for action expired. The City Council then approved moving the stone to the Fredericksburg Area Museum for public exhibition there, and placing an interpretive wayside panel at the corner of William and Charles streets where the stone had been located. A medallion with the outline of the stone would be placed in the sidewalk.

The mayor commented about the lengthy decision process:7

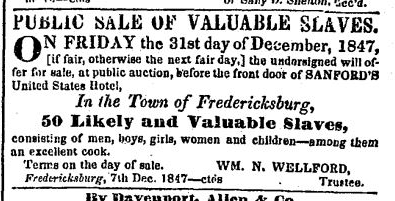

After the decision, owners of two buildings next to the slave auction block, 401 and 402 Williams Street, sued to keep the city from moving it. They feared that replacing the historic feature with a wayside panel would reduce tourist traffic and affect their businesses. The lawsuit argued that under the Dillon Rule, the City Council had authority to act only after the Architectural Review Board had issued a certificate of appropriateness.

owners of two buildings next to the stone (red X) sued to block its removal to the Fredericksburg Area Museum

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In response, the Fredericksburg Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) started a boycott of the businesses in 401 Williams Street. The owner of 402 Williams Street had rented it to a restaurant that was not associated with the lawsuit, and the NAACP was careful to note that no boycott was proposed of that restaurant. The owner of one of the buildings responded that the lawsuit reflected local politics and he was seeking to preserve history, while the NAACP stated that it:8

A Circuit Court judge ruled in February, 2020 that the city council had the authority to move the slave auction block. The council's action, after failure of the Architectural Review Board to grant a certificate of approval, did not exceed the authority granted to the city and thus violate the Dillon Rule. The city charter allowed local officials to manage and dispose of city property.9

the NAACP called for a boycott of businesses associated with the filer of a lawsuit trying to stop removal of the slave auction block

Source: Fredericksburg NAACP Branch

Despite the ruling, objections to moving the slave block continued. An architectural historian and former member of the Virginia State Review Board, Department of Historic Resources wrote a commentary published in the local newspaper, describing the slave block as:10

The Supreme Court of Virginia upheld the Circuit Court Ruling in April, 2020. The City Council acted in June, 2020, soon after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis led to widespread demonstrations and at least a temporary shift in public attitudes towards symbols systemic racism. Governor Northam and Richmond officials announced plans to move statues of Confederate leaders off Monument Avenue, generating nationwide news, and marches in Fredericksburg even blocked highways for short periods of time.

On June 5, the 800-pound Aquia sandstone block which had been installed in 1843 was excavated and moved to storage. City officials announced it would be loaned to the Fredericksburg Area Museum, which planned to incorporate it in an exhibit once the museum reopened after the COVID-19 pandemic.11

removal of the slave auction block on June 5, 2020

Source: City of Fredericksburg, Photos of Auction Block Removal

City officials decided to leave the red, white and green graffiti which had been spray-painted on the stone during Black Lives Matter protests, prior to its removal. The president of the Fredericksburg Area Museum stated:12

When the museum first displayed the object in 2021, the initial interpretation noted that 18 auctions of enslaved people occurred at the location of the slave block between 1847 and 1862. The block was placed in an obscure location, since the interpretive context had not been finalized and the display of profanity was a concern. Due to its weight, the slave block had to be exhibited on the first floor.13

Public reaction was that the auction block should not be obscured. In November 2022, the museum placed it in a highly-visible position for the exhibit "A Monumental Weight." The title referred to both the 1,000 pound physical weight of the chunk of Aquia sandstone, and also the moral and emotional weight of the block.14

In 2022, a research project into the history of Fredericksburg's black families include analysis of DNA. One man turned out to have haplogroup A000. That is considered the oldest genome, dating back to the ancestor known as "Y-line Adam" or "Y-chromosomal Adam" - the most recent common ancestor, living 254,000 years ago, from whom all men today are descended.

At the public event where the results of the study were revealed, the genealogist referenced the difference between the age of that genome and the slave auction block:15

graffiti added during Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 will remain on the slave auction block

Source: City of Fredericksburg, Photos of Auction Block Removal

In August 2023, the curator of African American history and special projects at the Fredericksburg Area Museum proposed to the City of Fredericksburg Memorials Commission how to display and interpret the block. She recommended inserting a series of text blocks along the curb of both Charles and William streets leading up to the corner, with text and images to provide context for the site. Embedded art such as a mosaic would mark the former location of the block, now in the Fredericksburg Area Museum. The site would also be illuminated at night.

The project was to be completed by 2025, together with a major new African American history exhibit at the museum.16

slave block in 1920

Source: Library of Congress, Slave Block, Fredericksburg, Va

an interpretive panel was installed at the site of the slave auction block

Source: City of Fredericksburg, Photos of Auction Block Removal