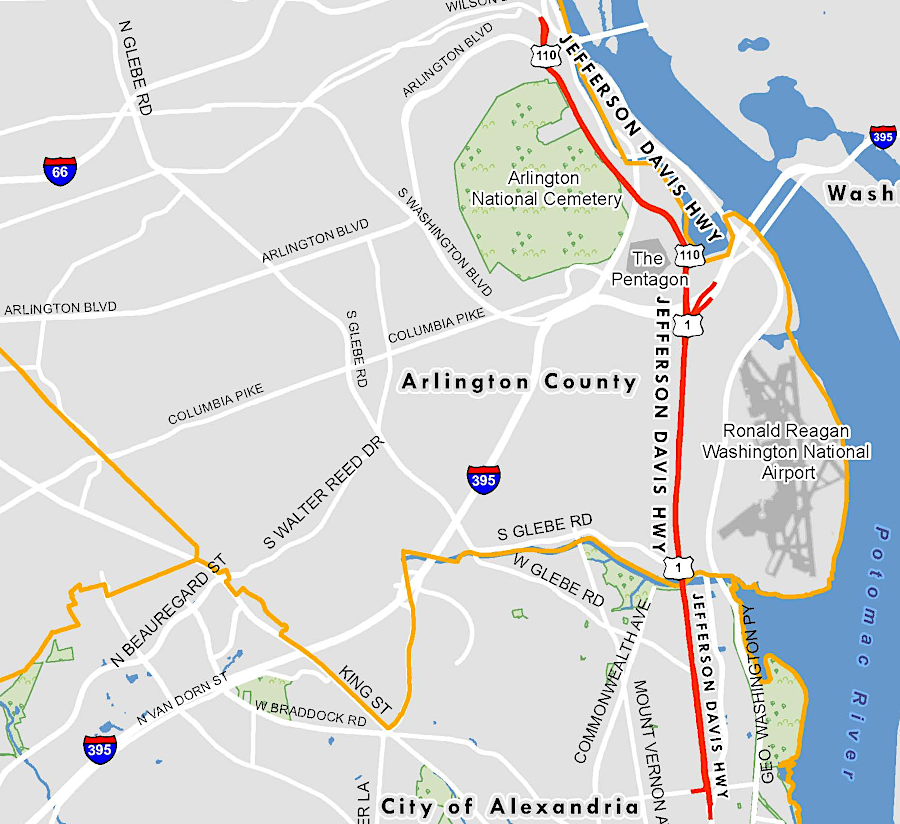

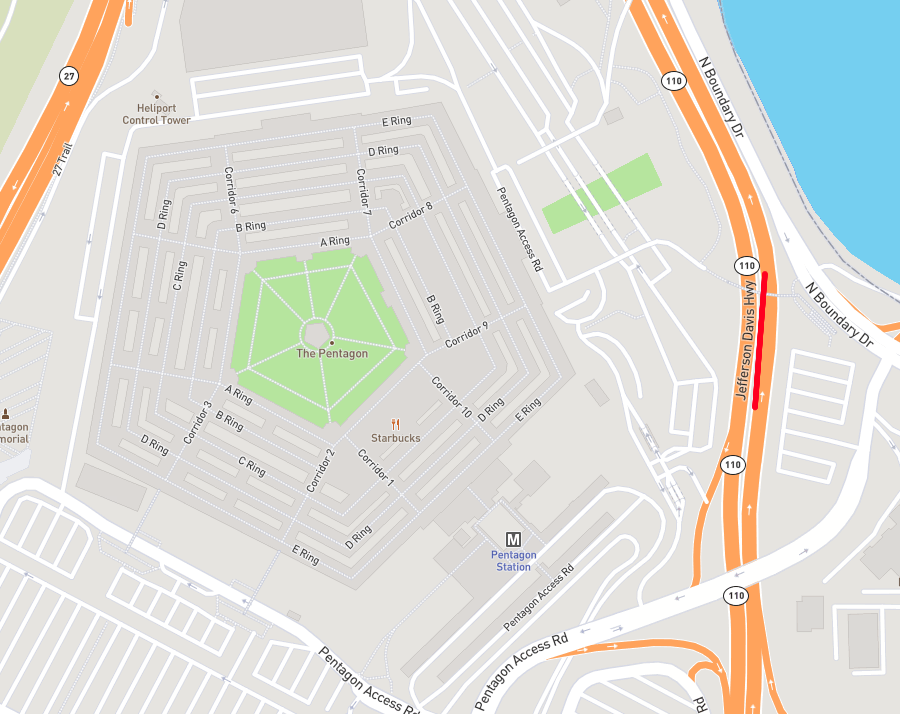

in Northern Virginia, the Jefferson Davis Highway name was applied to both Route 1 and Route 110 around the Pentagon

Source: City of Alexandria, Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Renaming Jefferson Davis Highway

in Northern Virginia, the Jefferson Davis Highway name was applied to both Route 1 and Route 110 around the Pentagon

Source: City of Alexandria, Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Renaming Jefferson Davis Highway

In 1913, before the standard system of assigning numbers to highways was established, the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) proposed naming a transcontinental auto trail after Jefferson Davis. It would be an "ocean to ocean highway from Washington to San Diego, through the Southern States...." The route would pass through seven of the capitals of the 11 states which had seceded in 1860-61.

The idea was a reaction to the proposal initiated a year earlier to define the shortest route connecting New York to San Francisco as the Lincoln Highway.

Jefferson Davis, as president of the Confederate States of America, had made many enemies among southern leaders between 1860-65. Being the leader of a failed cause that led to economic catastrophe did not make him popular with the general population in the Southern states either. However, harsh imprisonment by the Union Army at Fort Monroe after he was captured in Georgia in 1865 created sympathy for Davis.

After publication of his The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government in 1881, he was treated as a Confederate hero as advocates of the Lost Cause revised historical facts to match their cultural point of view. Davis was honored with a statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond in 1907.

The Honorary Chairman of the Jefferson Davis National Highway Committee wrote to the head of the US Bureau of Public Roads:1

The United Daughters of the Confederacy also proposed naming two other routes after the former president of the Confederate States of America. One connected Jefferson Davis' birthplace in Kentucky to his later home in Beauvoir, Mississippi. He wrote The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government there, and the house had become a memorial to honor him. The other was in Georgia, tracing the end of his flight before capture by Union troops. In 2001, a Mississippi state senator sought to have that state's legislature rename the stretch of road in her district "Jefferson Davis Highway," but the bill did not pass.2

After designing a distinctive marker for the Jefferson Davis Highway, the United Daughters of the Confederacy arranged for signs to be placed along the route. In the next decade, about 250 other private organizations were also establishing names for auto trails and erecting signs. The Federal government and state highway officials then partnered in a Joint Board to define a standard numbering system.

Efforts by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to get a single number assigned to the Jefferson Davis Highway were unsuccessful. The transcontinental road honoring the Confederate president ended up as part of US 1, US 15, and US 29. It used other highways westward, including US 80 from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama (now also designated the "Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail"), US 90 in Texas, and US 60 in Arizona.

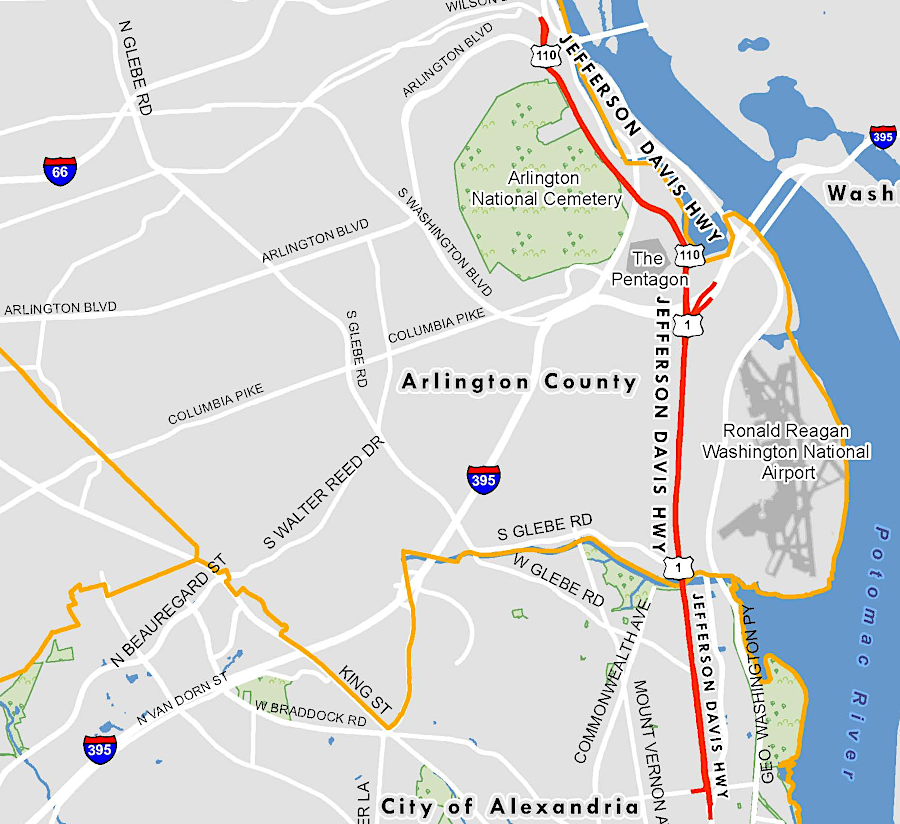

In 1922, the Virginia General Assembly designated an auto trail across the state as "Jefferson Davis Highway." The chosen route, the north-south route from Maine to Florida, had been designated by the legislature in 1918 as a primary highway and numbered Route 1. Near the North Carolina border, the auto trail designated in 1922 has been renumbered. It now jogs west to Clarksville on what today is US 58, then follows modern US 15 south to the state line.

the General Assembly designated the Jefferson Davis Highway in 1922

Source: Acts and Joint Resolutions, Amending the Constitution, of the General Assembly of the State of Virginia, 1922 (p.474)

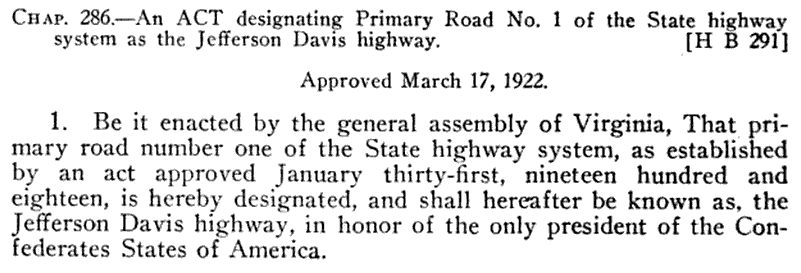

Within Virginia between 1913-1947, the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed 16 commemorative markers along the 235 miles from the Potomac River to the North Carolina border. Until completion of I-95, vacationers from the north going to Florida for the winter drove through Virginia on a highway honoring the one president of the Confederate States of America.

In 1926, a plaque was installed San Diego to mark the southwestern end of the road. In 1939, Route 99 north to the Canadian border was also labelled the Jefferson Davis Highway, and a monument in his honor was installed in Blaine, Washington.3

the United Daughters of the Confederacy installed a memorial stone at Proctor Creek in Chesterfield County in 1931

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 020-0561 Proctor Creek, Jefferson Davis Highway Marker

The last marker placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy was in Arlington County, at the start of the highway, in 1947. The original proposed location would have been within the boundaries of the District of Columbia. A site within the Federally-controlled district required approval from the US Congress, and representatives from northern states blocked it for years.

The barrier was overcome by locating a memorial stone to Jefferson Davis within Virginia, at the Virginia end of the 14th Street Bridge on Route 1. Over time, the 14-ton monument became an impediment to traffic. It was moved to the side of the road in 1964, after a fatal accident at the site.4

In 2015, a Change.org petition began advocating for removal of the name "Jefferson Davis Highway." Soon afterwards, a racist murdered nine people in a Charleston, South Carolina church and Southern jurisdictions began moving Confederate symbols away from places of honor. In 2017, pressure to act increased after a woman was killed in the white nationalist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville.5

The extent of the highway made it Virginia's largest Confederate memorial. Within Chesterfield County, the Jefferson Davis Highway was the only official "monument" honoring a Confederate leader. As an article in the Washington Post defined the challenge:6

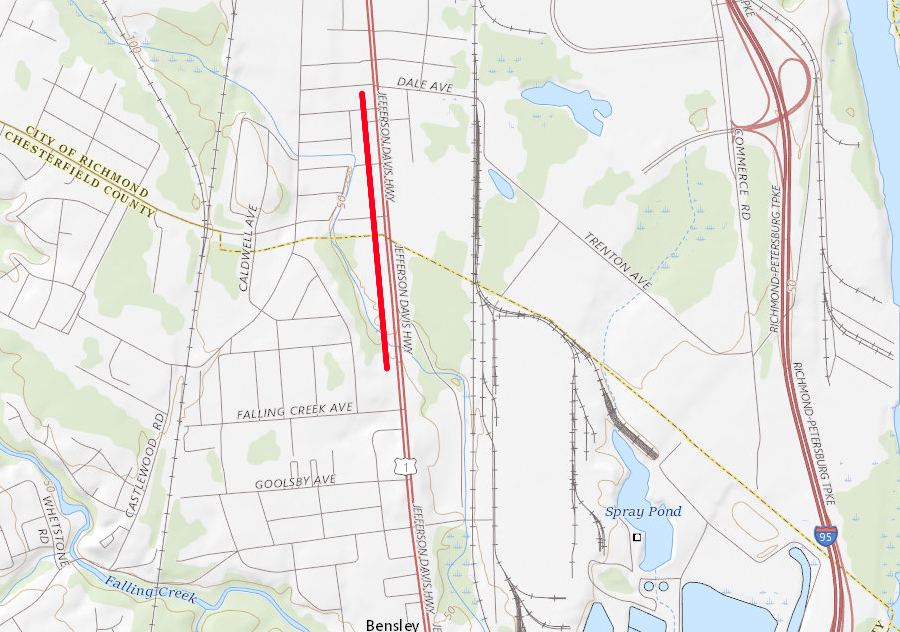

Jefferson Davis Highway (Route 1) parallels I-95 at the Richmond-Chesterfield County border, west of Deepwater Terminal

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Within Alexandria, street signs referred to Jefferson Davis Highway for the stretch of Route 1 south to where the road split into Patrick and Henry Streets. Within Old Town, no street signs referred to Jefferson Davis

The Alexandria City Council created an Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Confederate Memorials and Street Names in 2015, which recommended removing Davis' name a year later. The group did not recommend wholesale removal of other Confederate-related street names across the city. The history and intent of naming each street was different, and the city had a process for local residents to make specific requests.

The group also did not propose removing the "Appomattox" statue at the intersection of George Washington Memorial Parkway and Prince Street. The statue marked a specific historical event at that specific location, the withdrawal of the 17th Virginia Regiment as Union forces occupied the city on May 24, 1861. The group recommended additional interpretation, rather than statue removal. However, City Council decided to request permission from the General Assembly to move the statue. State approval was required, because a state law blocked local jurisdictions from moving historic war memorials.

In 2017, the city created a separate Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Renaming Jefferson Davis Highway to ensure a "robust community engagement process" before making a decision. Public suggestions for a new name, in addition to Richmond Highway, included:7

Arlington County lacked authority to change the Jefferson Davis Highway name without action by the General Assembly. Virginia is a Dillon Rule state, and only cities (but not counties) had been granted authority to rename roads. Arlington County had retained control over road construction and maintenance after passage of the Byrd Road Act of 1932, but did not have the power to change road signs.

Business owners in Arlington County complained that tenants would not choose to rent space, and conventions would not book hotels, in buildings with a Jefferson Davis Highway address. However, Northern Virginia representatives in the General Assembly calculated that the state legislature was unwilling to strip the historical name, dating back to 1922, from the road.

Del. Mark Levine, a member of the General Assembly from Alexandria, wrote bluntly in his constituent newsletter:8

in 2019, Richmond's tourism agency was still advertising Jefferson Davis Highway as a visitor attraction

Source: Visit Richmond

Del. Levine helped the Virginia Attorney General find another path in 2019. Based on obscure legislation, the Attorney General decided that the Commonwealth Transportation Board also had authority to allow Arlington County to rename the road.9

Arlington County quickly made the request, and the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved the switch and renamed the road as Richmond Highway on May 14, 2019. Governor Ralph Northam endorsed the change in a letter saying:10

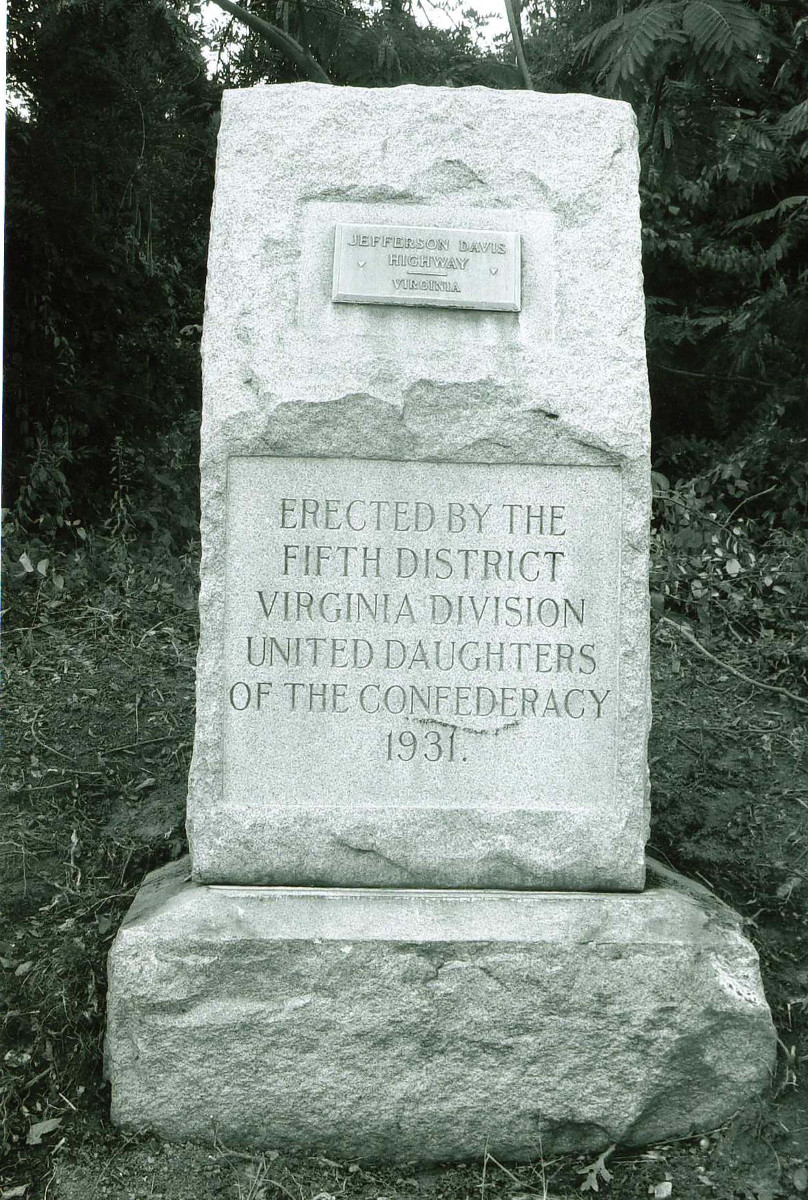

That 2019 change eliminated the designation as Jefferson Davis Highway for Virginia Route 110 past the Pentagon, and of Route 1 past the new Amazon headquarters.

Earlier that year, even before the Attorney General defined a pathway for a formal name change, news releases about Amazon's decision to chose Northern Virginia had used only "Route 1" to describe the road. GoogleMaps and other online services replaced the official name with "Richmond Highway" before Arlington had the opportunity to make the change officially.11

The US Postal Service determined that it would continue to deliver mail addressed to locations on "Jefferson Davis Highway," despite the name change. Because the Pentagon uses a Washington, DC mailing address, its mail has never included the highway name.12

Virginia Route 110 in front of the Pentagon was named Jefferson Davis Highway until 2019

Source: Driving Directions

1. E. S. Rafuse, "Jefferson Davis (1808–1889)," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, June 4, 2014, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/davis_jefferson_1808-1889; "Information About the Lincoln Highway," Lincoln Highway Association, https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/info/; Richard F. Weingroff, "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/jdavis.cfm (last checked May 15, 2019)

2.

3. "Opinion 19-010," Virginia Attorney General, March 21, 2019, https://www.oag.state.va.us/files/opinions/2019/19-010-Levine-issued.pdf; Richard F. Weingroff, "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/jdavis.cfm;

"A Short History of Beauvoir," Beauvoir - The Jefferson Davis Home and residential Library, https://www.visitbeauvoir.org/about-beauvoir; "Information About the Lincoln Highway," Lincoln Highway Association, https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/info/; "Plaque honoring Confederate president quietly removed from Horton Plaza Park in San Diego," Los Angeles Times, August 16, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-horton-plaza-confederate-20170816-story.html; "Proctor Creek, Jefferson Davis Highway Marker," nomination form to the National Register of Historic Places, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, April 20, 2008, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/020-0561_Proctor_Creek_Marker_2008_NRfinal.pdf; "Jefferson Davis Highway," Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jefferson_Davis_Highway (last checked May 15, 2019)

4. "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/jdavis.cfm; "14-Ton Monument to Jeff Davis Hasn't Been Stolen, Just Moved," The Washington Post, June 2, 1964, p.B2 (last checked May 15, 2019)

5. "Jefferson Davis Highway No More: Transportation Board Confirms Name Change By October," WAMU, May 15, 2019, https://wamu.org/story/19/05/15/jefferson-davis-highway-no-more-transportation-board-confirms-name-change-by-october/ (last checked May 15, 2019)

6. "Is it time to rename Jeff Davis Highway?," Chesterfield Observer, August 23, 2017, https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/is-it-time-to-rename-jeff-davis-highway/; "The largest Confederate monument in America can’t be taken down," Washington Post, August 22, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2017/08/22/the-largest-confederate-monument-in-america-cant-be-taken-down/ (last checked May 15, 2019)

7. "Final Report to Alexandria City Council," Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Confederate Memorials and Street Names, August 18, 2016, https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/manager/info/AdHocConfederateFinalReport-081816.pdf; "Route 1 name change ord" doclet memo, City of Alexandria, June 12, 2018, https://alexandria.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3529427&GUID=95FCD56B-00AF-431A-AB90-04AD1F019287&FullText=1; "Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Renaming Jefferson Davis Highway," City of Alexandria, https://www.alexandriava.gov/JeffersonDavisHighway; "City council approves Jefferson Davis Highway name change," Alexandria Times, September 21, 2016, https://alextimes.com/2016/09/city-council-approves-jefferson-davis-highway-name-change/ (last checked May 18, 2019)

8. "Naming Bridges and Highways," Virginia Department of Transportation, http://www.virginiadot.org/info/faq-highway-named.asp; "Naming highways, bridges, interchanges, and other transportation facilities," Title 33.2. Highways and Other Surface Transportation Systems, Chapter 2. Transportation Entities, Section 33.2-213, Code of Virginia, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title33.2/chapter2/section33.2-213/; "Who can change the names of roads in Virginia?," WTOP, August 20, 2017, https://wtop.com/arlington/2017/08/can-change-names-road-virginia/; "AG opinion paves way to rename Jefferson Davis Highway," Richmond Free Press, March 29, 2019, http://richmondfreepress.com/news/2019/mar/29/ag-opinion-paves-way-rename-jefferson-davis-highwa/ (last checked May 15, 2019)

9. "Opinion 19-010," Virginia Attorney General, March 21, 2019, https://www.oag.state.va.us/files/opinions/2019/19-010-Levine-issued.pdf; "Virginia agrees to let Arlington rename Jefferson Davis Highway," Washington Post, May 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/2019/05/15/e174356e-76b8-11e9-bd25-c989555e7766_story.html; "Arlington can rename Jefferson Davis Highway without going through legislators, AG opinion says," Washington Post, March 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/arlington-can-rename-jeff-davis-highway-without-going-through-legislators-ag-opinion-says/2019/03/22/c8cff8fc-4cb7-11e9-9663-00ac73f49662_story.html (last checked May 15, 2019)

10. "CTB Renames Jefferson Davis Highway In Arlington County; Names Amherst County Bridge After Fallen Trooper; Approves Round 3 Smart Scale Changes," Virginia Department of Transportation, May 15, 2019, https://www.virginiadot.org/newsroom/statewide/2019/ctb-renames-jefferson-davis-highway-in-arlington-county--names-amherst-county-bridge-after-fallen-trooper--approves-round-3-sm5-15-2019.asp (last checked May 18, 2019)

11. "Google Maps Now Displays Arlington Sections of Jefferson Davis Highway as ‘Richmond Highway,’" ARLnow, January 15, 2019, https://www.arlnow.com/2019/01/15/google-maps-now-displays-arlington-sections-of-jefferson-davis-highway-as-richmond-highway/; "With Amazon Coming, Arlington County is (Again) Trying To Rename Jefferson Davis Highway," DIist, November 16, 2018, https://dcist.com/story/18/11/16/with-amazon-coming-arlington-county-is-again-trying-to-rename-jefferson-davis-highway/ (last checked May 17, 2019)

12. "Arlington can rename Jefferson Davis Highway without going through legislators, AG opinion says," Washington Post, March 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/arlington-can-rename-jeff-davis-highway-without-going-through-legislators-ag-opinion-says/2019/03/22/c8cff8fc-4cb7-11e9-9663-00ac73f49662_story.html; "Virginia agrees to let Arlington rename Jefferson Davis Highway," Washington Post, May 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/2019/05/15/e174356e-76b8-11e9-bd25-c989555e7766_story.html; "State transportation board renames Jefferson Davis Highway in Arlington County," InsideNOVA, May 15, 2019, https://www.insidenova.com/news/arlington/state-transportation-board-renames-jefferson-davis-highway-in-arlington-county/article_4ffee412-773f-11e9-a6e0-af400af4bbe4.html (last checked May 17, 2019)