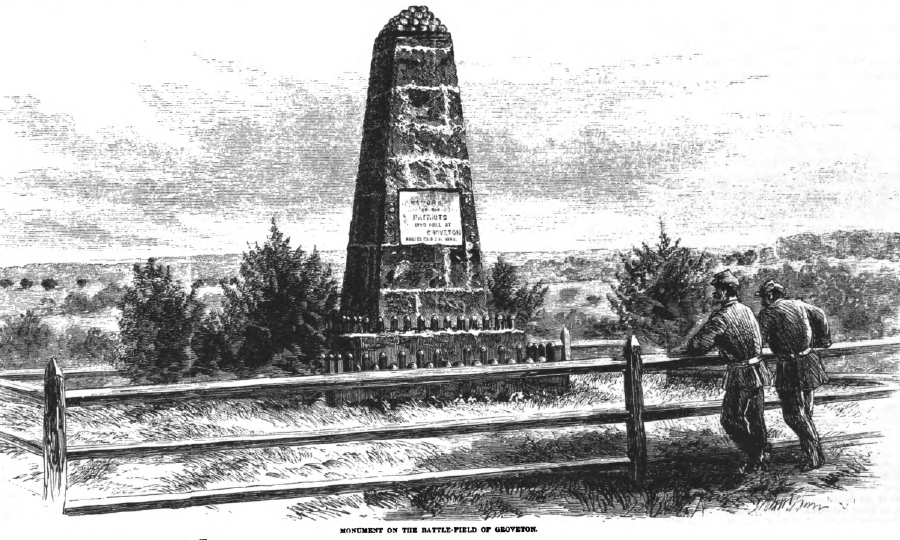

one of the first Civil War monuments constructed in Virginia honored Union soldiers who fought at Second Manassas

Source: Harper's pictorial history of the Civil War, Pope's Campaign in Virginia (p.389)

one of the first Civil War monuments constructed in Virginia honored Union soldiers who fought at Second Manassas

Source: Harper's pictorial history of the Civil War, Pope's Campaign in Virginia (p.389)

Virginia is covered in military monuments. Until some were removed after the muder of George Floyd in 2020, over 200 commemorated Confederates. There also are some which honor Union men or units as well.1

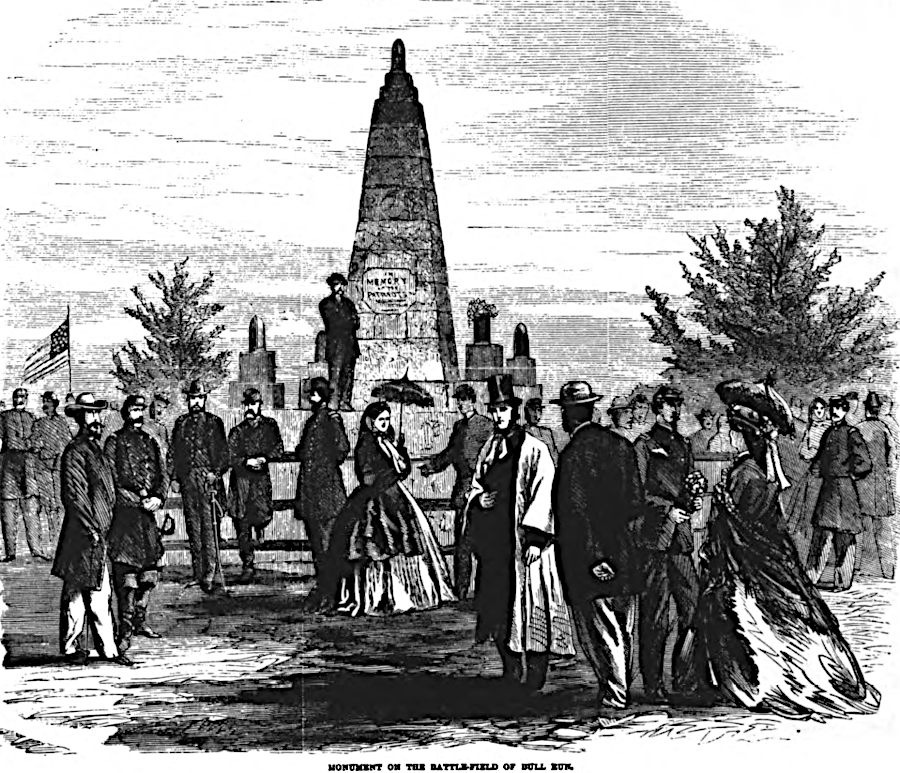

The first monuments to honor Union forces in Virginia were stone pyramids erected on the site of the First Battle of Manassas and the Second Battle of Manassas, known in the northern states as the First and Second Battle of Bull Run. The pyramids were constructed of local Triassic sandstone, and were decorated with shells and cannonballs. Plaques dedicated the monuments "to the patriots who fell," in recognition of over 10,000 Union casualties in the two battles.

The pyramids at Henry Hill (for First Manassas) and Deep Cut (for Second Manassas) were dedicated on June 10, 1865, after all Confederate forces had surrendered.2

Union-built monument at Manassas Battlefield

Source: Library of Congress, Monument on battlefield of Bull Run

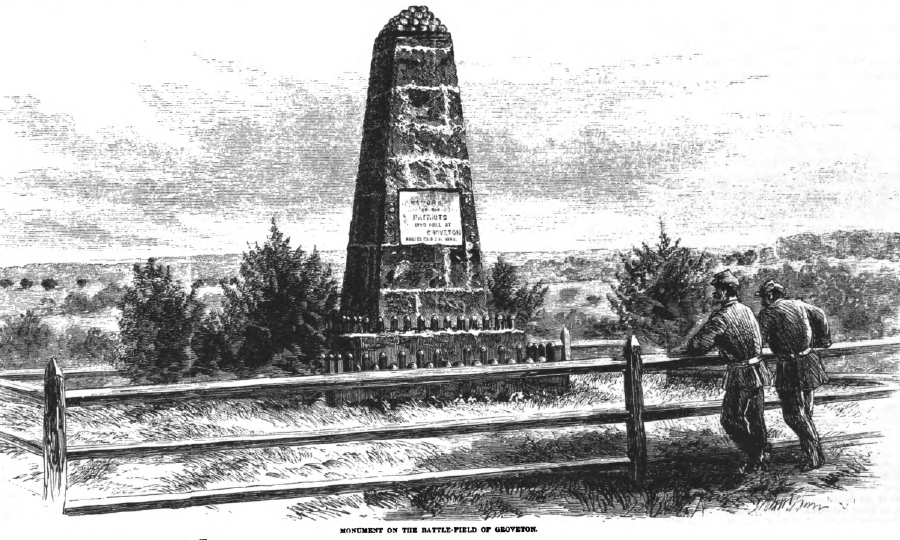

At the end of the Civil War, Union Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs designed a monument to the unknown Union and Confederate dead. He placed it on the grounds of Arlington House, which was owned by Robert E. Lee's wife. Meigs had chosen that plantation to be a new cemetery in 1864. By burying people next to Mrs. Lee's rose garden, he ensured the Lee family would never be able to return and sit on the porch to enjoy the view of the Potomac River and Washington DC.

The remains of 2,111 unidentified soldiers were collected from the battlefields around Manassas and the Rappahannock River. Some were excavated from shallow battlefield graves; many were just partial remains from bodies that were never buried. They were placed in a 20' deep pit with skulls, legs, arms, and ribs in separate sections.

A granite sarcophagus was placed on top before the site was dedicated in September 1866, in recognition that half of the war dead throughout the Civil War were also unknown. The initial Decoration Day ceremonies held at the monument honored just the Union dead.

In 1884, a Temple of Fame was built next to the Tomb of the Civil War Unknowns. A year later, names of Union Civil War leaders were engraved on the Temple of Fame, while new garden walks were constructed around the Tomb of the Civil War Unknowns. It was later upgraded with a fancier lid and a higher base.3

an Arlington Cemetery monument to honor the Civil War dead, dedicated in 1866, included unidentified remains from both Union and Confederate soldiers

Source: Library of Congress, Civil War Unknowns monument (c. 1866)

The 1,800-bed Union hospital at Fort Monroe during the Civil War benefitted from the service of women nurses, which were overseen by Dorothea Dix from 1861-1863. She led the effort in 1868 to build a 65-foot high granite obelisk on top of a 20-foot high base in the Hampton National Cemetery, where many of those who died at the Fort Monroe hospital were buried. Inscribed on it are the words:4

In Surry County, a land speculator from Delaware purchased much of the Claremont Manor estate in 1879-82. He sold tracts to people living in northern and midwestern states, attracting new settlers to the "Claremont Colony." The immigrants from north of the Potomac River had been supporters of the Union during the Civil War, and even established a chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic. In the local cemetery, they erected a monument with the words:5

In 1873, city officials in Norfolk created a cemetery for burial of African Americans. A 10-foot high brick wall separated it from the adjacent Elmwood Cemetery, used for graves of white people.

James E. Fuller, who served on the Norfolk Common Council between 1881-1889, got the new site renamed from "Potters Field" (and briefly "Calvary Cemetery") to West Point Cemetery. In 1886, the city dedicated a section of the cemetery for burial of African Americans who had served as Union Civil War soldiers and sailors, with space for a monument honoring them. Fundraising for a monument in the cemetery to honor US Colored Troops (USCT) began then.

The base of the monument was completed in 1906, but there was not enough funding for a statue until 14 years later. In 1920, after 35 years of fundraising, a life-size bronze statue of a black Union soldier was erected. It was located next to 58 headstones of Union veterans, which are aligned in three rows within Section 20.

It took even longer to erect a statue of a Confederate soldier next door in the whites-only Elmwood Cemetery. The pedestal for a monument was completed in 1912, but a statue there was not added until 2007.

The black Union veterans buried in West Point Cemetery are a small percentage of the 1,200 men of color from Hampton Roads who served in the Union Army. Most of the black men who served on the Union side in the Civil War ended up being buried elsewhere.

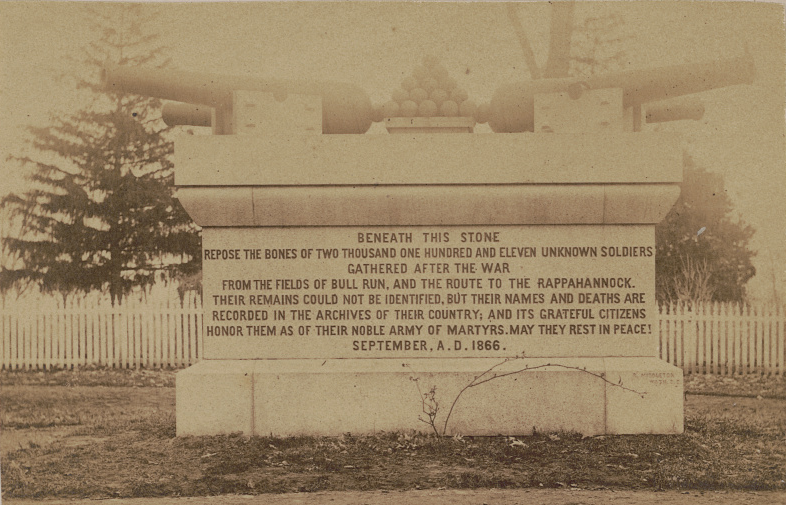

Nationwide, 180,000 black men served in the US Colored Troops (USCT), and about 37,000 of them died in the Civil War. About 135,000 of the men in the US Colored Troops escaped slavery before enlisting voluntarily in the Union army.

The model for the statue in West Point Cemetery was Sergeant William H. Carney of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. He was a native of Norfolk, and may be the first of 16 black men awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. The medal recognized his valor in grabbing the regiment's flag during the assault on Fort Wagner, when the color sergeant of the 54th Massachusetts was wounded. Sergeant Carney was then wounded four times, but proudly told his fellow soldiers who carried him to safety:6

Seargent William Carney waving the flag of the 54th Massachusetts on the breastworks of Fort Wagner, as Colonel Robert Gould Shaw is killed

Source: Library of Congress, Storming Fort Wagner (Kurz & Allison-Art Publishers, 1890)

Confederate supporters in Halifax County ordered a granite statue from the T.O. Sharpe Marble Company, and it was placed on a tall pedestal in preparation for an unveiling ceremony in 1910. The statue was one of several standard items made by the company for sale to both Northern and Southern customers. Before the ceremony, however, someone realized that the T.O. Sharpe Marble Company had shipped the wrong item from its catalog. In a "monumental error," Halifax County had received a statue of a soldier dressed in a Union uniform.

The Halifax County Camp of Confederate Veterans, the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and others in Halifax County made clear that the statue had to be replaced before any dedication ceremony. The Union soldier was removed from the pedestal and stored on the courthouse lawn temporarily. The company sent a granite Confederate soldier as a replacement, and chose not to pay getting the wrong statue shipped back. The Union soldier was eventually moved from the courthouse lawn to the Fairgrounds.

Dedication of a "correct" statue on April 17, 1911 solved the problem only briefly. A tree fell during a storm several years later and knocked the statue off the pedestal. The Confederate soldier was not replaced until 1937, when the Board of Supervisors funded a new statue in the middle of the Great Depression. The statue of a Union soldier is now on display in the South Boston-Halifax County Museum of Fine Arts and History.7

the Yankee monument delivered by mistake to Halifax County now is exhibited in the local museum

a Confederate soldier, erected in 1937, still stands in front of the Halifax County Courthouse

In 1907, residents of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania funded construction of a monument in Petersburg honoring the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. That unit, composed of coal miners, dug the tunnel and ventilation shaft used to initiate the Battle of the Crater. The monument is a statue of Col. George W. Gowen, who was briefly the regiment's commander after the battle, standing on a 20-foot tall granite base. Col. Gowen was killed at the spot where the statue was placed, as the regiment captured Fort Mahone on April 2, 1865.

Both Confederate and Union veterans attended the dedication in 1907. Governor Edwin Stuart of Pennsylvania and Governor Claude Swanson of Virginia attended the event as well. General Bolling, head of the A.P. Hill Camp of Confederate Veterans who had surrendered at Appomattox, said at the dedication:8

Governor Swanson assured the Pennsylvanians that the monument to a Union regiment located in Petersburg, Virginia would not be vandalized:9

Nearby in Petersburg National Battlefield, a memorial stone honors the US Colored Troops who served in the Union Army during the siege of Petersburg. The stone was placed where the troops made their first large-scale attack on June 15, 1864, in which they captured Confederate Battery Number 9. Later, the XXV (25th) Corps was organized to include exclusively US Colored Troops. The XXV Corps was sent to Texas after the Civil War, and disbanded two years later.10

Around 1916, a monument to the 25th Army Corps was placed in Lincoln Cemetery, an African-American cemetery in Portsmouth. The stone obelisk was erected by a local post of the Grand Army of the Republic.11

Another monument to a Union soldier was erected in 1925, north of Richmond.

On June 1, 1864, Charles Storke was in the 36th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry when he was captured in Hanover County. He was sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, then transferred to Andersonville Prison in Georgia. At the end of the war, he weighed only 95 pounds.

He ended up as a wealthy newspaper owner and mayor of Santa Barbara, California. In 1924, he bought land near where he had been captured and built a monument of polished Vermont granite. It honors the 137 men of companies B, E, F and G of the 36th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry who were killed, wounded, or captured with Charles Storke.

Storke donated the land and monument to Hanover County in 1925. He said at the time:12

In 2016, Norfolk named a local quarter-acre pocket park at the corner of Duke and York streets after Union Admiral David Farragut.

Farragut's first wife was a native of Norfolk. After she died, he married another woman from the same city. He was living in Norfolk at the start of the Civil War. He and his second wife left on April 18, 1861, after a convention in Richmond approved an ordinance of secession.

Captain Farragut commanded the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. He led the successful Union assault into Mobile Bay, during which he uttered the famous phrase "Damn the torpedoes. Full speed ahead!" He was later promoted to become the Navy's first full admiral.13

In 2021, a new monument was dedicated near Ebenezer Baptist Church at Maddensville in Culpeper County. It commemorated three soldiers of the 27th United States Colored Troops (USCT) Regiment, which was organized in Ohio. The regiment crossed the Rappahannock River as the Union Army began the Overland Campaign in May, 1864. The three black soldiers were captured by the 9th Virginia Cavalry and then executed.

The prime mover to create the monument noted:14

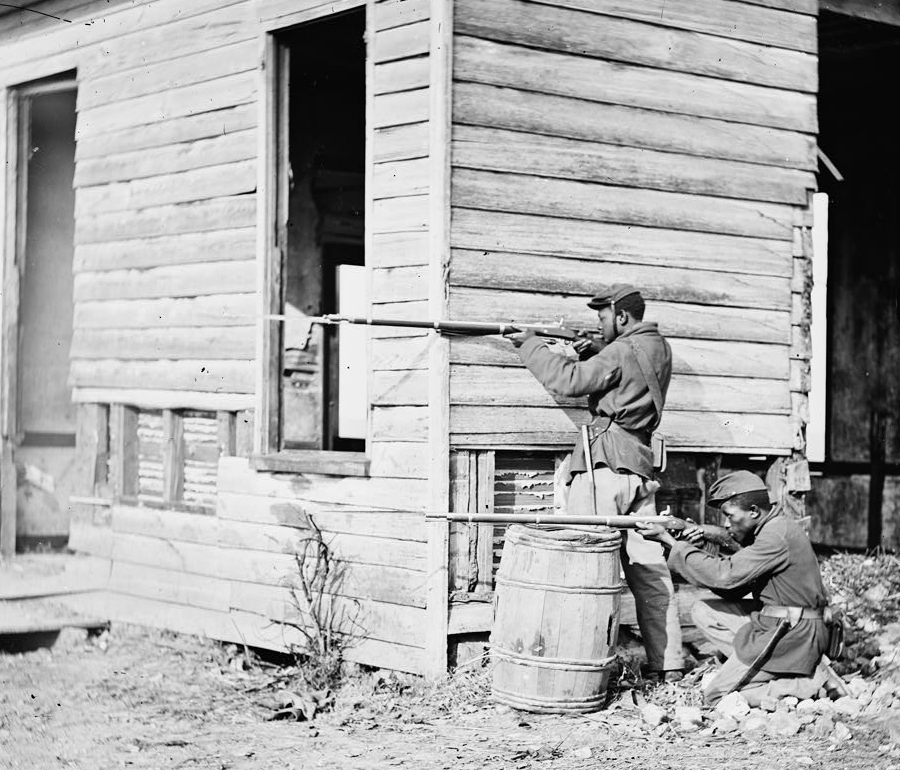

United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers are honored by a few monuments in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Dutch Gap, Virginia. Picket station of Colored troops near Dutch Gap canal

In 2021, a former member of the Northampton County Board of Supervisors led an effort to build a new monument on the Eastern Shore honoring Union soldiers. The leader's grandfather had been born enslaved, and had enlisted in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War.

After the United States Congress was forced to flee a mob that invaded the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, the Northampton Board of Supervisors voted to move the Confederate monument in Eastville. The Union Soldier Monument Advisory and Implementation Committee proposed a new monument very near the location of that monument, with the names of 2,300 Union and Confederate soldiers and sailors from the Eastern Shore. Because Union forces controlled the Eastern Shore by the end of 1861, the Confederate supporters had to flee and enlist in regiments from other locations.

On the Eastern Shore, white soldiers in the 1st Regiment Loyal Eastern Virginia Volunteers supported the Union. The vast majority of Union soldiers from the peninsula, 88% of them, were black men who joined the 7th, 9th and 10th United States Colored Troops when they were organized in 1863.15

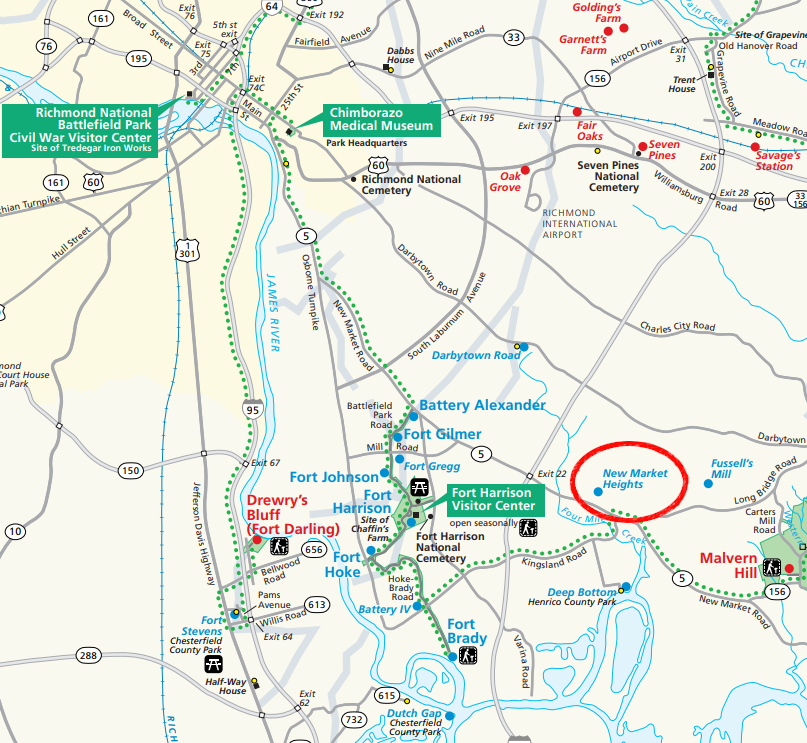

One site in Virginia has special significance for the US Colored Troops (USCT) that fought for the Union cause. The Capital Region Land Conservancy, with funding from the American Battlefield Protection Program and Viginia Land Conservation Fund, has protected land where the Battle of New Market Heights was fought on September 29, 1864.

Three brigades of US Colored Troops, about 3,800 men, were tasked with crossing Four Mile Creek and breaking through the Confederate defense line east of Richmond at New Market Road. Other Union forces attacked Fort Harrison.

the Battle of New Market Heights was part of an attack on the eastern edge of the Confederate defense line around Richmond in September, 1864

Source: Richmond National Battlefield Park, Park Map of every site in the Richmond National Battlefield Park system

Union General Benjamin Butler designed the attacks to evaluate if the US Colored Troops would be effective fighters, after poor leadership at the Battle of the Crater had led to a slaughter of the US Colored Troops in that engagement. Their success in capturing New Market Heights that day demonstrated both their capacity and their courage.

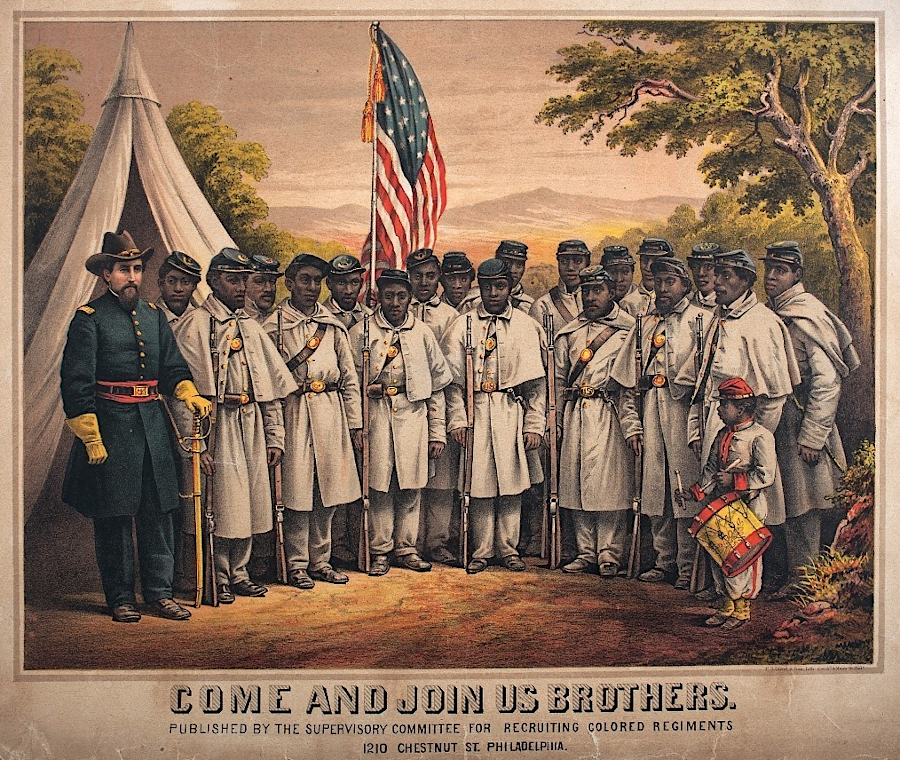

the prominent role of US Colored Troops at the Battle of New Market Heights makes that site distinctive in Virginia

Source: US Army, A History of African American Regiments in the U.S. Army

General Butler General Benjamin Butler personally commissioned a medal to recognize the valor of US Colored Troops at the Battle of New Market Heights. He also sought public recognition by nominating members of the US Colored Troops for the Medal of Honor, which had been created by the US Congress in 1862 to honor bravery on the battlefield.

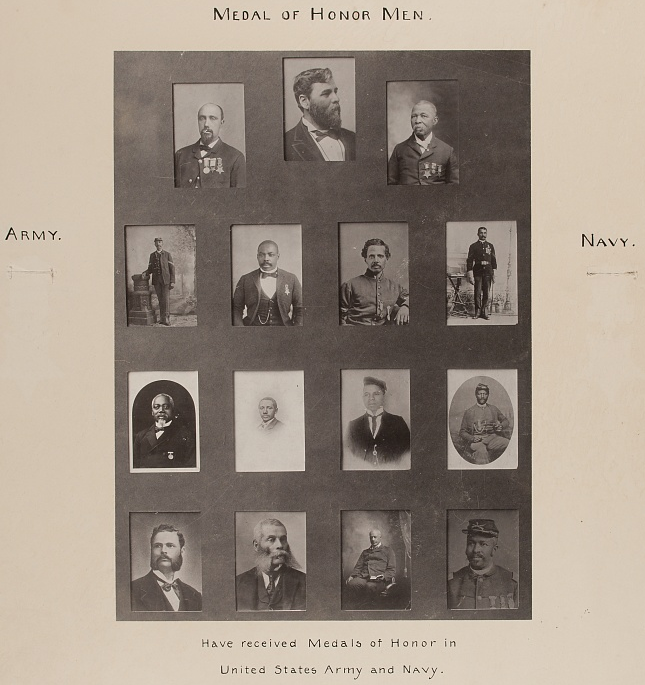

The War Department approved granting the Medal of Honor to 14 men. During the Civil War, the Medal of Honor was granted to 1,520 men and one woman. Though 10% of all the Union soldiers were black, just 1% of the recipients of the Medal of Honor were black. Of the 21 black soldiers and sailors to earn the Medal of Honor, 14 were at the Battle of New Market Heights.

In 2022, developers abandoned plans to build a 650-home subdivision known as The Ridings on 420 acres, about half of which was associated with the Battle of New Market Heights. That created the opportunity for public acquisition of the property. The Capital Region Land Conservancy highlighted why preservation of yet another Civil War battlefield was justified:16

In 2025, Henrico County planned to build a 3.2-mile-long paved, shared-use path linking the New Market Heights battlefield to the James River. The $16 million trail also would connect the Virginia Capital Trail to Deep Bottom Park, where the United States Colored Troops (USCT) crossed the James River before marching north to New Market Heights.

The Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association planned to build a monument on the battlefield honoring the United States Colored Troops (USCT) who fought there. Henrico County incorporated the monument in its planning:17

an exibit at the Negro Exhibit of the American Section at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900 identified 18 African-American men who had won the Medal of Honor

Source: Library of Congress, Medal of honor men Have received medals of honor in United States Army and Navy

In Franklin County, a local resident who had been the first group of black students to integrate the public schools failed to convince the Board of Supervisors to relocate the Confederate statue standing in front of the courthouse. The original 1910 statue had been destroyed in a 2007 truck wreck, but it was replaced in 2010.

More than 90% of Franklin County residents were white, and in a 2020 nonbinding referendum 70% had voted to keep the monument in its prominent place. Subsequent research identified 70 Franklin County men who had served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) - 69 soldiers and one sailor. In 2023 a county resident proposed to build a monument honoring them on the courthouse lawn. The chair of the Franklin County Board of Supervisors indicated he might support that proposal:18

The Franklin County NAACP chapter launched the "Raising the Shade 1850-1910" project to erect a statue honoring local U.S. Colored Troops. In 2023, it received a $285,000 grant from the Monuments Across Appalachian Virginia project administered by Virginia Tech, which was distributing $3 million donated by the Mellon Foundation. Sculptor Paul DiPasquale, who had already produced a statue of Arthur Ashe on Monument Avenue in Richmond and a statue of King Neptune on the Virginia Beach boardwalk, agreed to create a bronze statue.

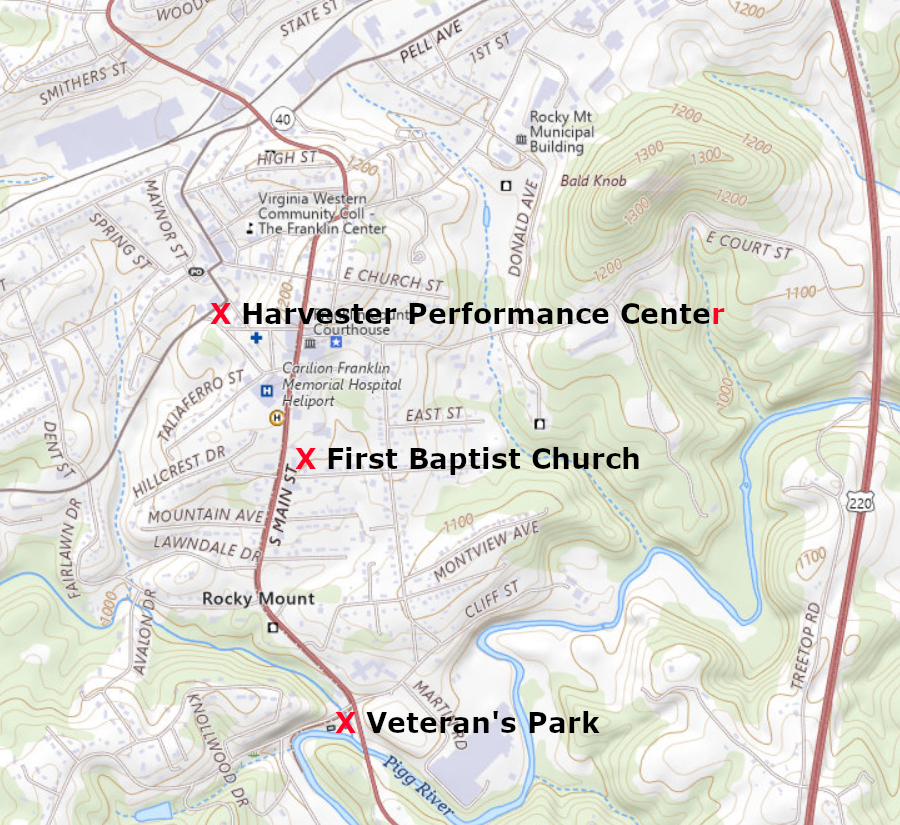

On June 20, 2024, the Franklin County Veterans' Memorial Commission voted 6-5 in support of placing the monument in Veterans Memorial Park in the Town of Rocky Mount. At Veterans Memorial Park, there was already an obelisk naming military members who had died in previous wars. The 70 black US Colored Troops (USCT) were not listed on that monument. The day following the 6-5 vote, three of the five on the losing side of the vote (including the Veteran Commission's chair and vice-chair) resigned without making any public statements explaining their reasons.

One alternative location for a US Colored Troops monument was near the farmers market and Harvester Performance Center in downtown Rocky Mount. That site had far more foot traffic that the existing obelisk memorial in Veterans Park.

The Town Council had to approve placement on town-owned land. In September the Town Council voted unanimously to ask the Franklin County NAACP chapter to agree to a memorandum of understanding which the chapter president had already rejected. The two needed to cooperate because the Monuments Across Appalachian Virginia grant that would fund the statue was provided to the NAACP chapter, not directly to the town.

One town member made the council's stance clear:19

The final compromise was to locate the seven-foot high bronze statue of a US Colored Troops (USCT) soldier at the site of the former First Baptist Church in downtown Rocky Mount. The church, founded by black residents in Franklin County, completed the building in 1907 but moved to a newer structure in 1965.

It was private property and no decision was required by the town council, but the mayor expressed support for that location and offered town resources for the monument's upkeep there. The old church building, which the congregation had already planned to convert into a community center, was a more visible and accessible location than Veterans Memorial Park.

The monument was dedicated on January 18, 2026, 16 months after the groundbreaking ceremony. When the decision on the location was finalized, Mayor Holland Perdue summarized the community's satisfaction with finding a solution that met the desires of the NAACP's Raising the Shade committee for a highly-visible location:20

the First Baptist Church ended up as the site for a statue honoring local U.S. Colored Troops in Rocky Mount

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Arlington County erected a sign in 2024 to honor United States Colored Troops based at Fort Ethan Allen in late 1865. The 107th Regiment had been organized in at Louisville, Kentucky between May-September 1864. The regiment participated in the siege of Petersburg, the capture of Fort Fisher in North Carolina, and the Campaign of the Carolinas until the surrender of the Confederate army led by General Joseph Johnston. The troops occupied forts guarding Washington, DC until being mustered out on November 22, 1866.

At the unveiling of the sign, the Chief Executive Office of the Virginia Tourism Corporation said:21

At the University of Virginia (UVA):22

The 69 students and faculty members who fought for the Union during the Civil War have not been memorialized by the university, but it has honored the Confederates. On June 7, 1893, the Monument to the Confederate Dead was dedicated in the Confederate Cemetery with the inscription "Fate denied them victory but granted them glorious immortality." Charlottesville had been a hospital center during the Civil War, and 1,097 Confederate soldiers ended up buried in the Confederate Cemetery.

That Confederate monument was next to the University Cemetery created in 1828, plus the separate burial site of enslaved workers and their families who helped construct the buildings of the University of Virginia. The graveyard of the enslaved was forgotten, until discovered in 2005 when the University of Virginia planned to expand the University Cemetery.

The 67 grave shafts found in the African American Cemetery have been enclosed within a wooden fence, and an interpretive marker tells the story of that site. However, no plaque or monument on the grounds of the University of Virginia honors the Union soldiers who fought for emancipation.23

the valor of the US Colored Troops in the 1864 Battle of New Market Heights was honored by special medals

Source: Wikipedia, Medals in the National Museum of American History

the First Manassas battlefield became a place for remembering Union soldiers at a place where they were defeated by the Army of Northern Virginia

Source: Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, Pope's Campaign in Virginia (p.391)