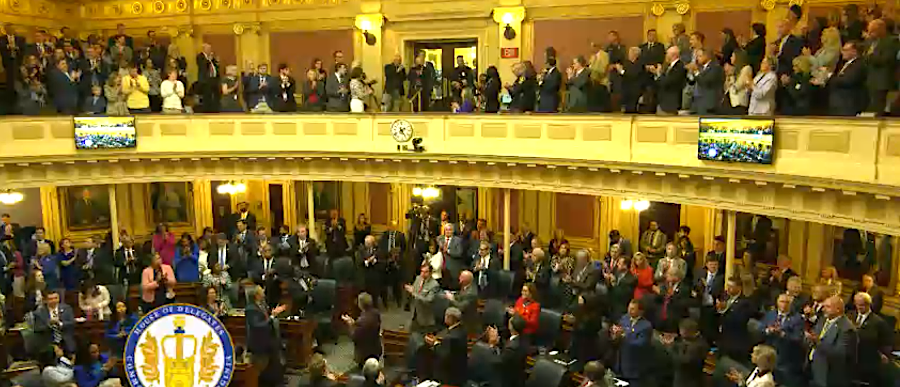

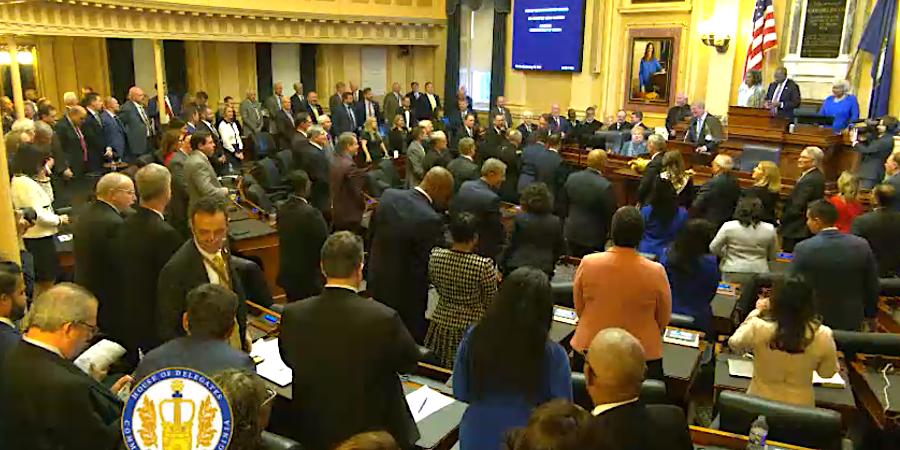

from the perspective of the Speaker of the House of Delegates looking at the 99 other members, the Republicans are seated on the right and Democrats on the left

from the perspective of the Speaker of the House of Delegates looking at the 99 other members, the Republicans are seated on the right and Democrats on the left

At the state level, the Virginia legislature is called the General Assembly. It is the oldest elected representative body in the United States in continuous operation.

The General Assembly started in 1619 as the "Grand Assembly" when the colony was a private corporation run by the Virginia Company and Jamestown was the colonial capital. The concept and implementation of representative government through the Grand Assembly survived the switch from private company to royal colony in 1624.

King James I died soon after deciding to revoke the charter of the Virginia Company. The charter was a business contract between the king and the private investors in the Virginia Company, and it was not clear how Virginia would be governed without a charter.

Charles I issued "Proclamation for setling the Plantation of Virginia" and defined Virginia as a royal colony within two months of becoming the monarch. However, he let fifteen years of uncertainty pass before formally recognizing the legitimacy of the General Assembly in 1639. In the vacuum of royal direction, the General Assembly assumed it had the power to govern the colony. It even "thrust out" a governor appointed by Charles I, forcing John Harvey to return to England.

In 1632, the Grand Assembly repealed all existing laws and then passed 61 laws. That was necessary to clarify what laws had been amended or repealed, and what laws were in effect. Many of the 61 laws were simply renewals of the repealed laws, but one in particular was new. It articulated a bold claim that the powers of the royal governor were limited, and only the Grand Assembly had the authority to levy taxes on the colonists:1

The Grand Assembly divided into two parts in 1643 when Governor William Berkeley arrived. The appointed Council of State (Governor's Council) began to meet in a separate location. The meeting of the elected burgesses became the "House of Burgesses." Governor Berkeley made the division in part because there were two factions. The merchants and planters who sought to direct all of the tobacco trade to England, where they had influence, ended up as members of the Council of State. Smaller planters who sought to trade with the Dutch comprised the new House of Burgesses.

After Charles I was beheaded in 1649, both the General Assembly and Governor Berkeley declared their allegiance to his oldest son as King Charles II. Until 1652, Virginia's leaders ignored the power of the Rump Parliament and New Model Army in England. Similarly, those who had seized control of the English government in London had more important issues to address than colonial policy.

At the end of 1651, Parliament sent four commissioners to Jamestown with instructions for all colonial officials to submit to the authority of the new Commonwealth in England. Governor Berkeley was forced out of office peacefully; he went into forced retirement at Green Spring. One of the commissioners, Richard Bennett, was chosen to serve as governor between 1652-1655.

In the instructions to the four commissioners, Parliament did specify that the General Assembly would continue in operation. In a separate action, Parliament altered the balance of power within the colony. The 1751 Navigation Act blocked trade with the Dutch, ending the competition which Governor Berkeley had enhanced in a 1647 deal that encouraged them to purchase tobacco in Virginia and raise prices accordingly.

In Virginia, banning shipments from the colonies to the Netherlands enhanced the influence of the wealthy planters in the Council of State and a group of allies in the House of Burgesses. They were well-connected with the English merchants that now controlled all tobacco purchases. The Navigation Acts blocked the legal trade of the smaller planters; ships from other European nations were no longer allowed to arrive at wharves in Tidewater.

Trading with Dutch and French ships continued, but through smuggling. The officials in Virginia who were responsible for regulating the tobacco trade lacked a navy to enforce the Navigation Acts, even if they had wanted to do so. The colony was essentially undefended. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) and the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), Dutch ships sailed into the Chesapeae Bay and captured English ships loaded with tobacco.

The Interregnum period in Virginia lasted from 1752-1660, when the governor and members of the council were no longer appointed in London. The instructions brought by the commissioners gave the House of Burgesses the authority to elect all colonial officials.

The two commissioners who reached Virginia (Richard Bennett and William Claiborne; two others drowned during the trip) plus Samuel Mathews led a faction that controlled the House of Burgesses. That faction was supported by the London merchants who benefitted from the Navigation Acts and gained a monopoly on trade, after the end of legal competition with buyers in other countries.

The Interregnum governors retained the power to call for elections to the House of Burgesses. That was a practical matter. The burgesses met for just a short period of time and then dissolved. In essence, every burgess was term-limited; members did not retain their position after a session had finished. To initiate a new meeting of the House of Burgesses, someone had to call for new elections. The governor was given that task between 1652-1660.

When Charles II was restored to the throne, the House of Burgesses chose Governor Berkeley to serve again. He sailed to London and returned in 1662 with a new appointment from King Charles II.

In his second stint as governor, he sought to implement policies that were unpopular with the leading planters. They were unwilling to diversify away from the dependence on tobacco, or to develop port towns where the royal officials could regulate trade and collect taxes.

Governor Berkeley manipulated members of the House of Burgesses after the 1662 session and gained control, in part by offering well-paid appointed jobs to allies. In addition to dissolving a House of Burgesses and requiring new elections, the royal governor had the power to prorogue a General Assembly and force it to stop meeting until he recalled it. To ensure his allies maintained their power, Governor Berkeley chose to keep in session the House of Burgesses whose members had been elected in 1662. For 14 years during the "Long Assembly," there were only intermittent elections to replace individual members who died/resigned.

Governor Berkeley's attempt to control the fur trade (primarily deerskins) with Native Americans blocked others who sought to gain wealth from that business. The colonists saw the governor's attempts to maintain peace with the tribes as appeasement. His unwillingness to defend those willing to live on the edge of English settlement eventually led to Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.2

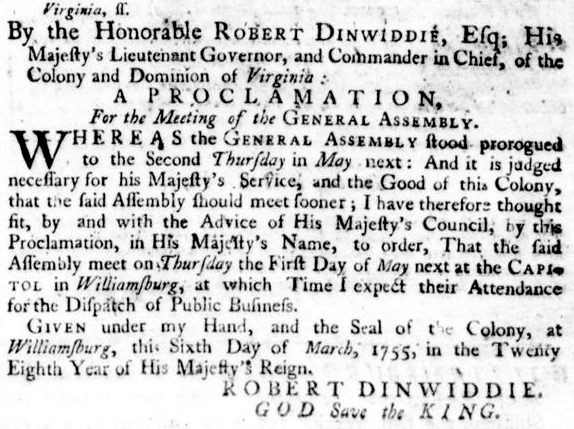

at the start of the French and Indian War, Gov. Dinwiddie called the General Assembly into session

Source: Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia Gazette (Hunter: March 21, 1755, p.4)

When the General Assembly was not in session, the governor and his Council of State/Governor's Council were responsible for making decisions. Traditionally a new governor would, upon arrival, call for new elections and start with burgesses that had a fresh mandate from those allowed to vote.

After the French and Indian War, the respect for royal government and the willingness to comply with orders from London faded in the 13 colonies. Efforts to impose taxation without representation led to economic boycotts. Particularly in Virginia, constraints on expanding settlement westward into the Ohio River Valley spurred the wealthy land speculators with economic social and political authority to question the benefits of being part of the British empire.

In Massachusetts, objections to the 1765 Stamp Act were expressed by a mob destroying the home of Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Leaders in the separate colonies began to correspond with each other, creating a sense of unity and common purpose which had been lacking at the start of the French and Indian War.

The March 5, 1770 "Boston Massacre" and the 1773 Boston Tea Party led to the city of Boston being occupied by British Regulars and closure of the port. Proposals in different colonies for banning the import of British goods and exports to Great Britain were controversial, but to be effective the separate colonies would have to agree on a common strategy to pressure Parliament. To negotiate a standard approach, 12 of the 13 colonies sent representatives to a Continental Congress in 1774.

Such a meeting was not authorized by royal officials, but colonial leaders began to ignore royal guidance and establish coordinated policies that were independent of the officials appointed by King George III. After Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in May, 1774 after it called for a day of feasting and prayer in support of Boston, the burgesses arranged for voters to elect representatives to an extra-legal convention at the same time they elected representatives for a new House of Burgesses.

What is known today as the First Virginia Convention met in Williamsburg two months later. Members elected an 11-person Committee of Safety to govern the colony. By replacing the role of the appointed Governor's Council, the authority to make decisions shifted from appointed to elected officials.

Governor Dunmore was traveling to the Ohio River to lead an army in Dunmore's War, so the planned November 1775 session of the House of Burgesses was postponed.

A proposal by the Committee of Safety for Lord Dunmore to call the House of Burgesses into session in early 1776, to respond officially to his offer to pardon the rebellious Virginia leaders, was rejected. Dunmore declined to give the Virginians an opportunity to use the official form of government to pass legislation opposing King George III's policies and to provide an official patina to the creation of an army.

The Second Virginia Convention met at the Henrico Parish Church (now known as St. John's Church) in Richmond on March 20-27, 1775. A dramatic "give me liberty or give me death" speech by Patrick Henry led to a decision to establish a colony-wide army, uniting the independent militia companies in preparation for war with British troops. The convention also elected representatives to the Second Continental Congress; across North America, the structure of government was shifting.

By the time Lord Dunmore fled the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg on June 8, 1775 and took refuge aboard a British warship in the York River, the power of an appointed Governor's Council had evaporated. Key members had joined what was developing into a rebellion or retired to their Tidewater mansions. Voters were electing representatives to serve in conventions; there was no longer a need for a House of Burgesses whose laws would be subject to veto by Governor Dunmore or King George III.

The House of Burgesses last met on May 6, 1776. A total of 45 burgesses assembled in their wing of the Capitol and declared there was a lack of quorum. Someone wrote "Finis" in the minutes. As soon as the burgesses left the room, the elected members of the Fifth Virginia Convention came in and began to meet. There were 126 eligible members plus six alternates for the Fifth Virginia Convention. They decided to became an independent state on May 15 and adopted Virginia's first constitution on June 29.

the journal recording the last meeting of the House of Burgesses concluded with a flourish

Source: Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia

In the new state constitution, the House of Burgesses was recast as a House of Delegates. Each county continued to elect two delegates, as did the district of West-Augusta. The city of "Williamsburgh" and the borough of Norfolk were each allowed to elect one delegate. Delegates served one year terms, so there was an election every year.

The 1776 state constitution made the legislature bicameral, with an elected State Senate as well as an elected House of Delegates. The General Assembly was required to meet annually. Members of the House of Delegates served one-year terms. State Senators served four-year terms, after the initial cycles of elections.

Continuing the pattern used for elections to the House of Burgesses, each county and the district of West Augusta elected two people to the House of Delegates.

For the new State Senate, the 64 counties were arranged into 24 districts. Senators were granted a four-year term, with 25% of the seats up for election each year. Four divisions of state senators were defined for the first election in 1776. That started the rotation cycle so six senators would be elected annually. In contrast, 100% of members of the House of Delegates were elected annually starting in 1776.

In the six districts which were categorized within in the first division, senators were elected to serve terms of just one year. Starting in 1777, senators in the first division were elected to serve for four years. For districts within the second division, the first six senators were elected in 1776 to serve two years terms. Those elected in 1778 began to serve four-year terms.

Similarly, senators in the third division were first elected in 1776 to three year terms. The 1779 election initiated the four-year cycle for those six districts. Starting in 1780, all state senators were elected to serve full four year terms.

counties and the district of West-Augusta were clumped into 24 districts for electing state senators in 1776

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1779, a Committee of Revisors established by the General Assembly submitted 126 bills to revamp colonial legislation which was outdated by independence, and did not reflect the new republican principals. The first item in the package was "A Bill To arrange the counties into Senatorial districts," calling for a revision of the specific counties arranged within the 24 districts. The bill was not addressed during wartime.

In 1785, the House of Delegates took up the bill and passed it. By then, the General Assembly had created 14 new counties (Powhatan, Fluvanna, Henry, Montgomery, Washington, Kentucky, Ohio, Yohogania, Monongalia, Shenandoah, Augusta, Rockingham, Greenbrier, and Rockbridge) while eliminating Fincastle, East Augusta, and West Augusta. However, the State Senate rejected the bill.

Realignment of counties within the 24 State Senate districts finally occurred in 1792. The 1830 constitution drew 32 State Senate districts, and the 1850 constitution created 50. The 1864 constitution adopted by the Restored Government of Virginia reduced the State Senate to 34 members, after creation of West Virginia had reduced the size of Virginia by 1/3. The 1870 constitution increased the number to 40, and that number has not changed since then.

Drawing State Senate districts based on geography, rather than population, continued until the US Supreme Court ruled in the 1964 in Reynolds v. Sims case that districts had to be equal in population.3

There are 140 members of the General Assembly now, 40 members in the State Senate, and 100 members in the House of Delegates. Voters elect the 100 Delegates to the House of Delegates every two years., and the 40 State Senators serve 4-year terms. Elections to the General Assembly are held in odd-numbered years such as 2017 and 2019, while elections to the US Congress (the Federal legislature) occur in even-numbered years such as 2016 and 2018.

After the Civil War, black men were elected as both delegates and state senators. Between 1890-1967, no blacks served in the General Assembly. That pattern began to change in 1967, when Dr. William Ferguson Reid was elected to the House of Delegates from a Richmond district.

Reminiscing in 2025 about taking office as the only black person among 140 members of the legislature, Dr. Reid said:4

From 1869-1882, control of the General Assembly shifted between "Funders" and "Readjusters." Conservatives sought to limit the political and social options for the newly-freed slaves, and objected to paying higher taxes to support public schools for them. Funders supported using state revenues to repay the pre-war debt obligations for transportation projects, maintaining the state's credit and future ability to sell bonds. Readjusters called for reducing the state's repayments based on post-war economic distress, and using more of the state revenues to provide services to citizens.

In 1882, conservative Democrats took control of the General Assembly for the next 90 years. In 1902, a revised state constitution restricted the electorate and blocked most blacks from voting.

In 1909, Virginia's Equal Suffrage League started advocating for allowing women to vote in Virginia. In 1920, enough states ratified the 19th Amendment to add it to the US Constitution. Virginia's General Assembly waited another 32 years before it ratified it, in what was by then just a symbolic gesture.

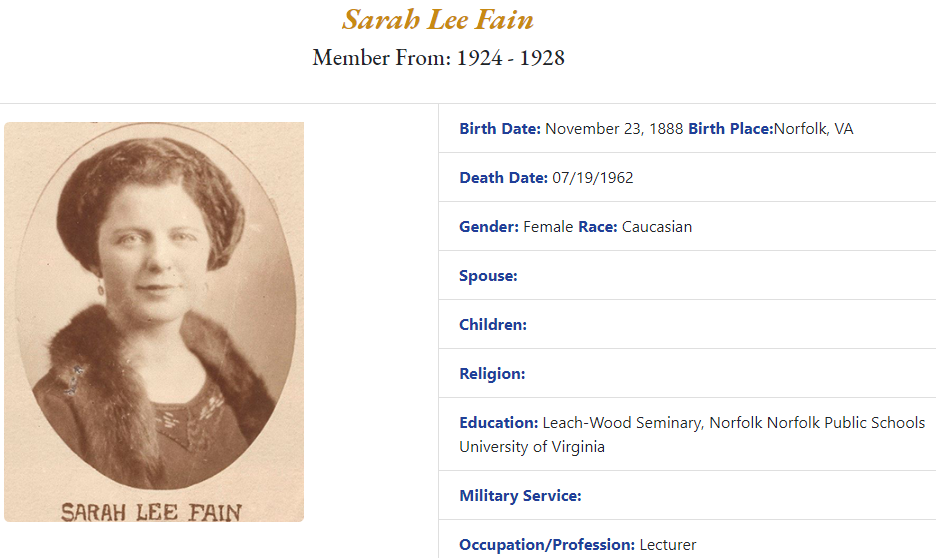

Norfolk voters elected the first women to serve in the Virginia legislature since it started in 1619. Sarah Lee Fain and Helen T. Henderson were elected to the House of Delegates in 1923.

The Database of House Members (DOME) listed 9,637 names of members who served in the General Assembly until 1643 and the House of Delegates between 1643-2019. It included just 91 women for that timeframe.

One of those was Yvonne Miller. She was the first African-American woman elected to the General Assembly in 1984. She too was elected from Norfolk, and her election reflected in part the demographics of that area.

Population changes in other urban areas resulted in later increases in diversity. In 2017, voters in Prince William County elected the first transgender delegate and the first two Latina delegates. Fairfax County voters elected the first Asian-American member, and Richmond voters elected the first openly lesbian woman to the House of Delegates.

After the 2019 elections, 41 of the 140 members were female. The Speaker of the House of Delegates, the Majority Leader, and the House clerk they hired were all women. The election of the first woman to serve as the Speaker of the House, Eileen Filler-Corn, occurred 100 years after passage of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution giving women in Virginia the right to vote and 400 years after the first meeting of a "Grand Assembly" in Jamestown.

The rules adopted by the House of Delegates in 2020 flipped the standard use of gender-based pronouns. References to "gentlemen/gentlewomen" had been dropped after the 2017 election of a transgender member to the House, and the 2020 rules replaced "he/him" with "she/her." Duties for all positions were described with "She will..." The Speaker stated clearly:5

The same Washington Post story which described the Speaker's opinion also quoted how a male delegate responded to the shift in pronouns:

Sarah Lee Fain was one of the first two women to serve in the General Assembly

Source: Virginia House of Delegates, Database of House Members

The Byrd Organization dominated Virginia politics between the 1930's and 1970's. It supported the election cycle where state officials were chosen in separate years from Federal officials. The conservative, "keep taxes low" Senator Harry Byrd advocated in odd-numbered years for Democratic candidates to be elected to state and local offices. In even-numbered years, the Senator supported conservative Republican candidates or maintained a "golden silence."

Senator Byrd died in 1965, when the few Republicans serving in the General Assembly were powerless. The Republican Party was the alternative to the Byrd Organization, so it was relatively liberal compared to the Democrats. The Republicans blocked blacks from participating in party conventions in 1920 and ran a "lily-white" ticket for state offices in 1921, but the national Republican Party was still the Party of Lincoln.

At the national level, the Republican Party was viewed as more conservative and the Democratic Party was viewed as more liberal, but in Virginia it was the opposite. The key issues protecting Democratic control were keeping taxes low, and ensuring whites had more economic and social opportunities than blacks.

In the 1950's, Senator Byrd was a key leader in the Massive Resistance movement to block school desegregation in Southern states. In Prince Edward County, the local county government kept the public schools closed for four years, in hopes of perpetuating the separate-but-equal system - even after Federal courts had determined "separate" was far from "equal."

In 1969, the Democratic Party in Virginia split and the state elected its first-ever Republican governor, Lynwood Holton. The political tides shifted, and the old political alignments fell apart in 1973.

That was the year of "Armageddon," according to a book of that name by Virginia election scholar Larry Sabato. The state Democratic Party was unable to agree on a nominee for governor. Liberal Democrats united behind progressive populist Henry Howell, while former Democratic governor Mills Godwin switched parties and ran for the office as a Republican. Conservative Democrats chose, like Godwin, to acknowledge they were now Republicans at the state as well as the national level.

Under decades of Democratic control, policy debates focused on how to raise taxes and distribute revenue. Different regions of the state competed for government funding, and the rural/urban divide was a common basis for debate.

Elected members tended to be re-elected, in part due to redistricting every 10 years that defined safe seats for powerful incumbents. Dick Saslaw was elected to the House of Delegates from Fairfax County in 1976. He ended up serving in the General Assembly for 44 years; fellow members at the end of his career joked that he once served with Patrick Henry. When Saslaw first arrived in Richmond, the Speaker of the House was the child of a Civil War veteran.

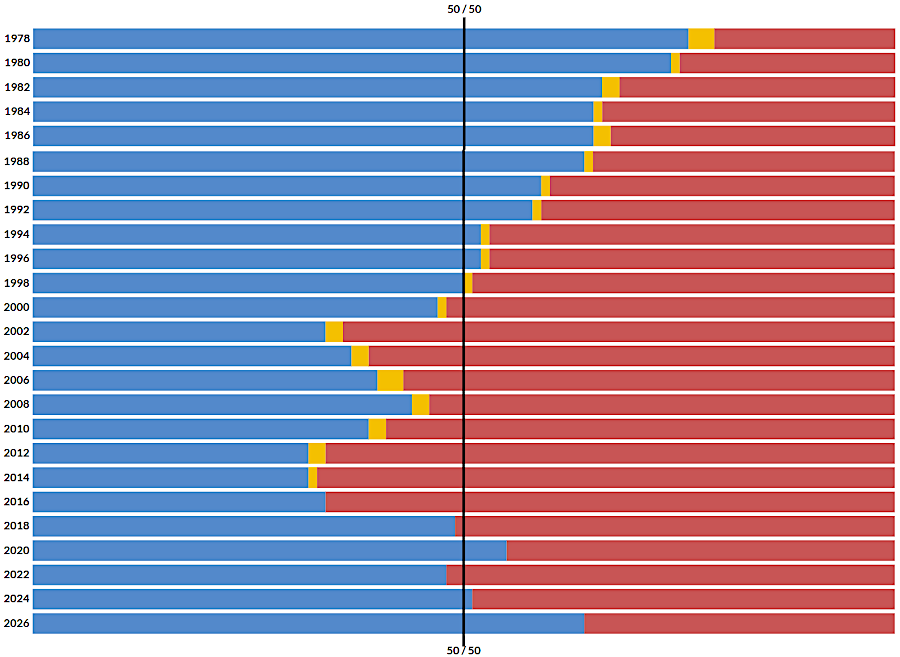

Until 1997, Democrats controlled the House of Delegates. After the 1997 election, their majority was just 51-49. Governor Jim Gilmore, a Republican, chose a Democrat to serve in his administration. In the special election that followed, the seat flipped to a Republican and created a 50-50 split. Before the new Republican was sworn into office in January, 1998, the Democrats elected a Speaker of the House. Eventually, the two parties negotiated a power sharing agreement with co-chairs of all committees.

Governor Gilmore also convinced a Democrat in the State Senate to take a job in the Virginia Department of Transportation. A Republican won the subsequent election to fill his seat, and that flipped control of the State Senate to a 21-19 Republican majority.

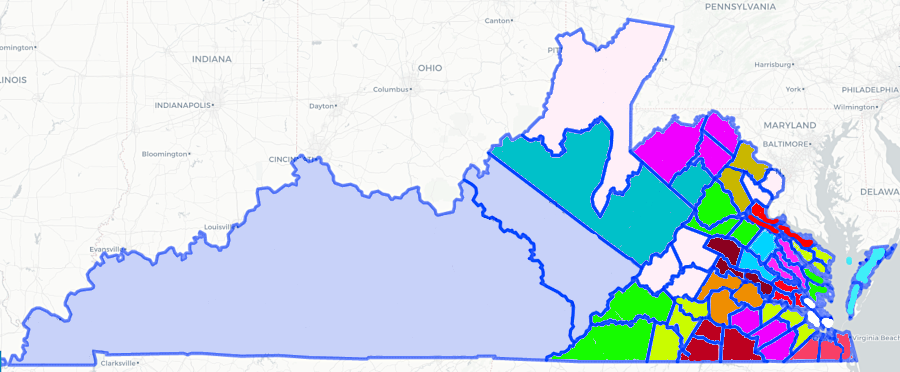

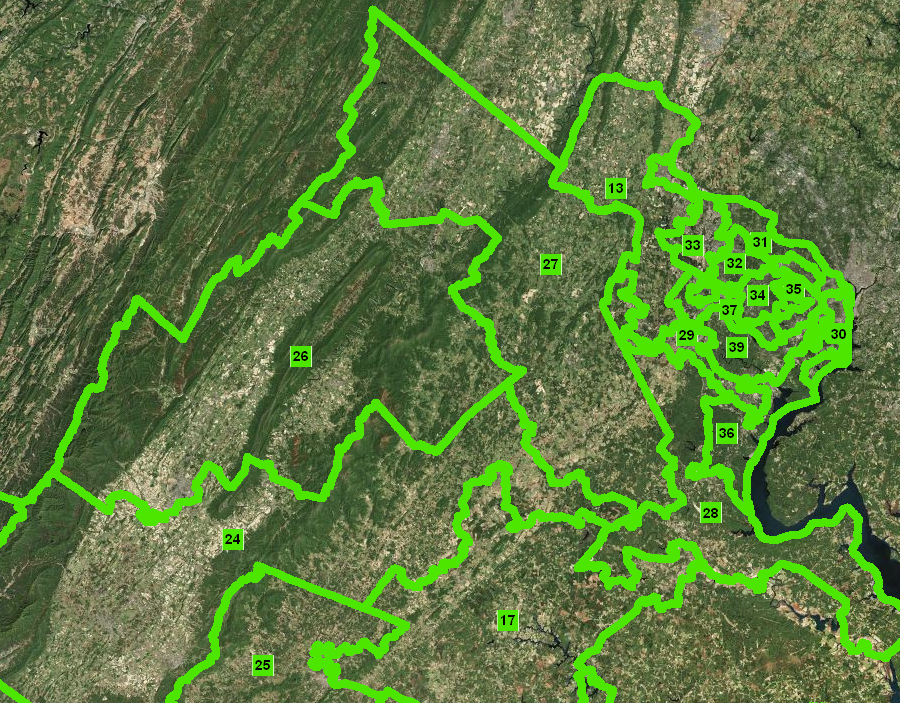

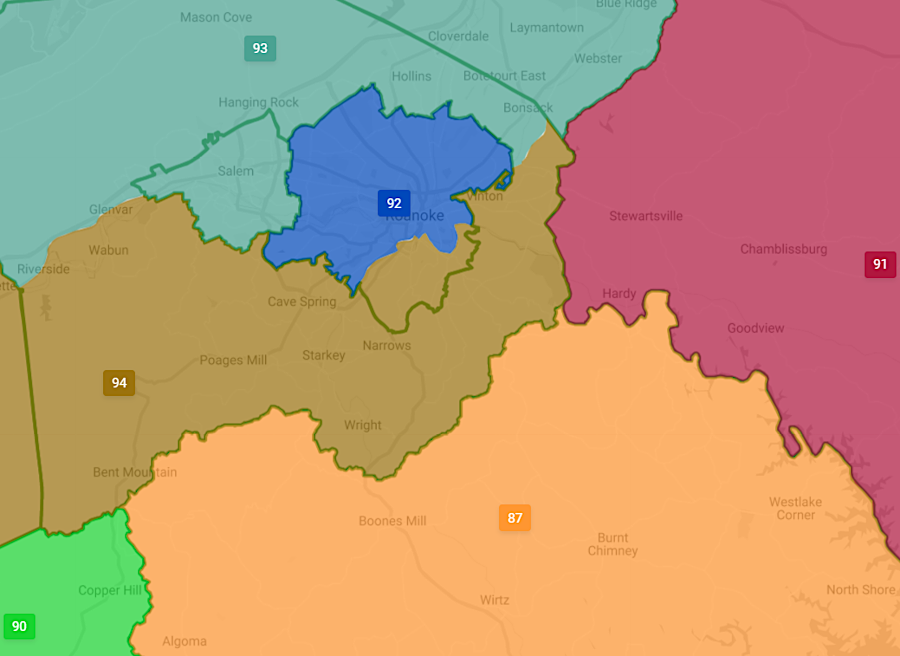

after the 2010 Census, boundaries of State Senate districts were redrawn - and clearly show how population is concentrated in Northern Virginia

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting 2010

In the 2011 election, the Republicans won control of the State Senate. Before that election, the Republicans controlled the House of Delegates but Democrats controlled the State Senate by a majority of 22-18.

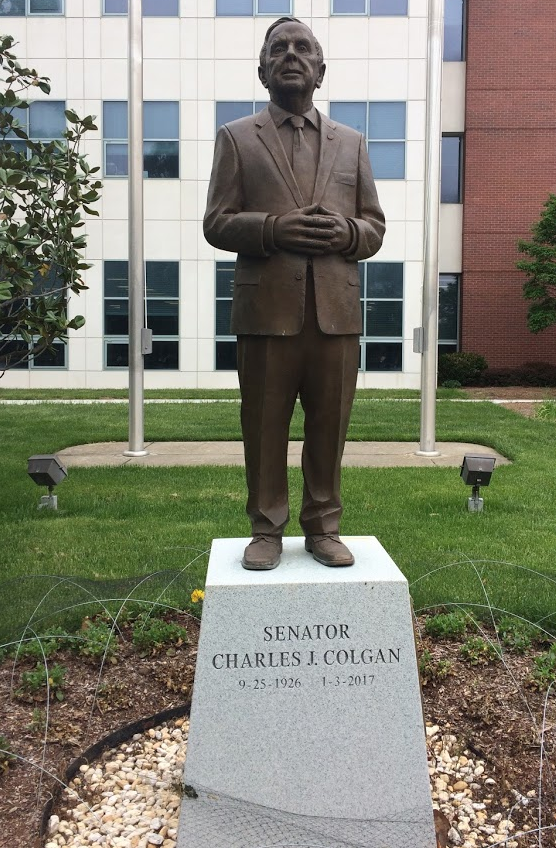

The Republicans won a net of two Senate seats in 2011, allowing the Lieutenant Governor (a Republican) to break tie votes. The Lieutenant Governor decided the state constitution blocked him from breaking ties on the votes to approve the budget, so the budget in 2012 was delayed. Finally, one Democrat (State Senator Charles Colgan from Prince William County) voted to approve the budget, and it passed 21-19.

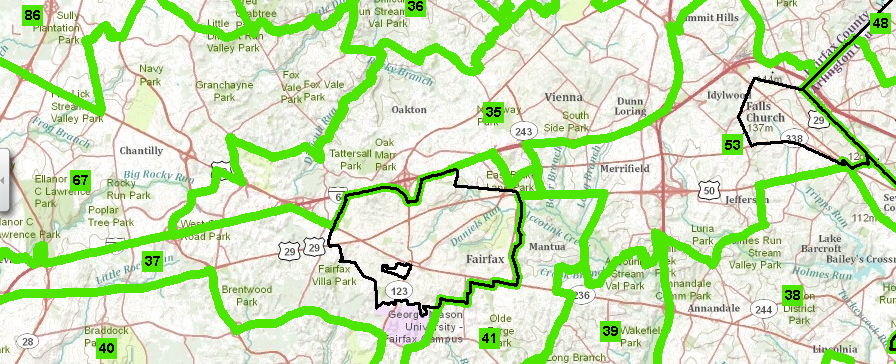

House of Delegates districts near GMU Fairfax campus, after 2010 redistricting (the City of Fairfax, outlined in black, is a different political jurisdiction than the County of Fairfax)

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services

Despite the significance of the 2011 election, in which control of the State Senate hung on a switch of just 2 seats, only 15 of the 40 contests for State Senate had only one major party candidate on the ticket. Only 27% of the major party House of Delegates races included contests between Republicans and Democrats, and in many of those contested elections one of the Republican/Democratic candidates had "no experience, no money, no campaign organization and no hope of victory."6

Redistricting allowed incumbents to shape districts that ensured re-election, consolidating Republican-supporting voters in some districts and overloading other districts with Democrats to create safe seats - and equivalent "packing" occurred by Democrats when they controlled a portion of the General Assembly. Thanks to the power of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology, politicians could choose their voters when election districts were revised after every Census - until 2020, when the voters approved a constitutional amendment and created a bipartisan Virginia Redistricting Commission.

When the members of the Virginia Redistricting Commission failed to agree on any maps in 2021, the Supreme Court of Virginia had to establish boundaries for 100 new House of Delegates districts, 40 State Senate districts, and 11 US House of Representatives districts. The commission had no role in revising local election districts for city councils and county supervisors. Local governments remained responsible for updating voting precinct boundaries to eliminate "split precincts," so election officials in a precinct would not have to give different ballots to voters based on their address.7

the Virginia Redistricting Commission considered different proposals for redistricting the House of Delegates in 2021, but failed to adopt any map

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, B7 STATEWIDE HOD

Prior to the Baker v. Carr US Supreme Court decision in 1962 that voting districts had to have approximately the same number of people, the political machine of Harry Byrd had structured Virginia districts so urban areas were under-represented and Byrd's rural supporters elected an excessive number of General Assembly members. Once the urban areas received full representation, the General Assembly politics changed - and after 1965 Virginia voters approved borrowing money for roads, building a community college system, and selling liquor-by-the-drink in public restaurants.

Ethnic and racial biases still affect Virginia's politics, but Virginia's population is too diverse, and too concentrated in urban/suburban areas, for a rural-based "organization" to dominate the state again. The swing vote that determines the winner in statewide elections is now concentrated in areas with a blend of urban and rural characteristics - the suburbs, places such as Loudoun, Prince William, Stafford, Chesterfield, Chesapeake, Gloucester, and York counties.

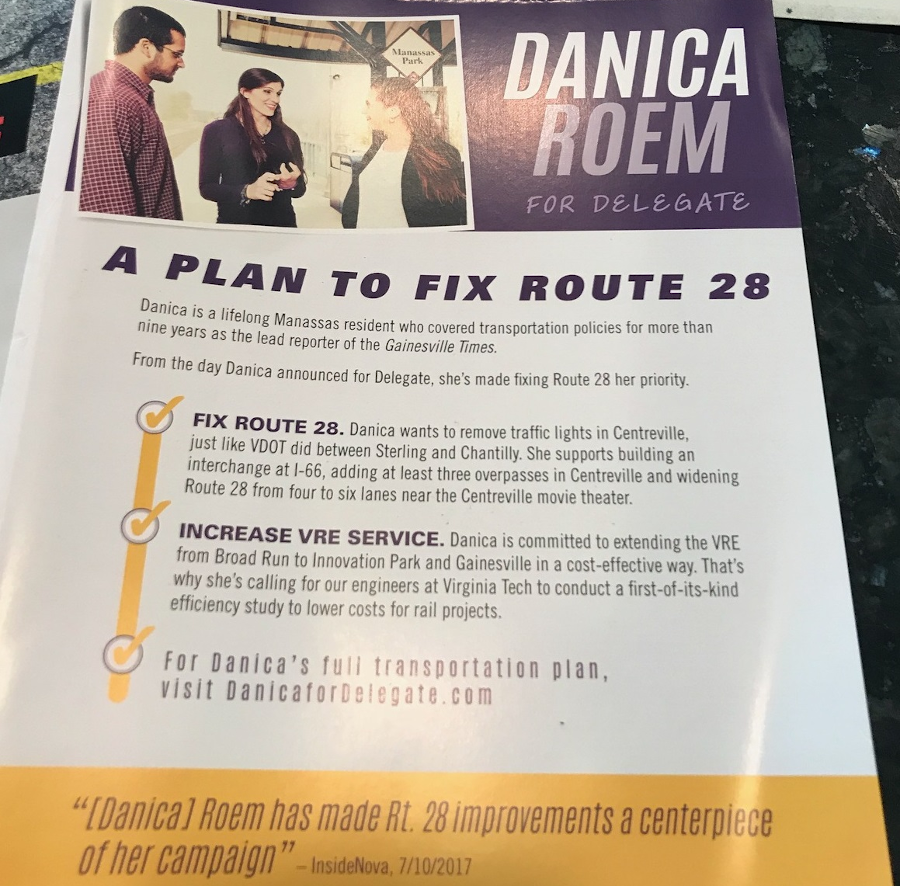

Del. Danica Roem (13th District) hosted one of her many town halls on transportation in July, 2018, but few voters chose to attend that particular meeting

The legislature met annually for most years in the colonial period, and after Virginia became an independent state in 1776. The 1851 state constitution changed the General Assembly meetings to biennial sessions.

Under the current state constitution, the General Assembly sessions start on the second Wednesday in January. The legislature is supposed to meet in "short" sessions of 30 days in odd-numbered years, such as 2025, and meet for 60 days in even-numbered years. The two-year (biennial) budget is passed in the longer 60-day sessions.

That schedule means the legislature maintains a high level of control over the state budget. Governors elected in an odd-number year inherit the biennial budget proposed by their predecessor.

Governor Glenn Youngkin, elected in 2021, inherited a proposed biennial budget for FY22 (July 1, 2022-June 30, 2023) and FY23 (July 1, 2023-June 30, 2024) that had been drafted by previous Governor Northam with different priorities. Gov. Youngkin had little time before the scheduled end of the session to get the legislature to redirect funding through amendments toward his FY22 priorities.

In 2023, like previous governors he proposed a FY23 "caboose bill" to the General Assembly to modify the last year of the budget which his predecessor had prepared. In 2024, Governor Youngkin finally proposed his own FY24-26 budget. His successor, Democrat Abigail Spanberger who was elected in 2025, inherited a biennial budget proposed for FY26 (starting July 1, 2026) and FY27 that Governor Youngkin had drafted.

A legislative session may be extended for an additional 30 days; typically the 30-day sessions are scheduled for 46 days. On occasion, the clock in one house of the legislature is stopped so the session can continue beyond midnight on the last day of a session to complete a key bill.

The state constitution requires only that the legislature meet once each year. The Governor may call the General Assembly into a special session, a technique used at times when the two-year budget has not passed before the next fiscal year starts, when a particular issue requires more time for debate, or when an unexpected issue arises that requires a quick response. The legislators may also force the Governor to call a special session by a 2/3 majority.

In 2025, the Democrats held just a narrow majority of each house and the Governor was a Republican. The Democrats wanted a special session to highlight the impacts of President Trump's policies, anticipating the extra attention would mobilize votes for Democrats in the November 2025 elections. The Republican Governor was unwilling to call a special session, and the legislators could call themselves into special session only by a supermajority vote. There were enough Republican legislators to block such a call.

However, the 2024 General Assembly already had authorized a special session. It was intended to deal with a complicated budget issue involving the Virginia Military Survivors & Dependents Education Program, and the State Senate (controlled by Democrats) had not closed that special session. At the end of the 2025 General Session, the Democrats controlled both houses. They approved by majority votes in each house to expand the scope of the 2024 special session to allow action on any:8

The Democratically-controlled State Senate remained in special session through the rest of Governor Youngkin's term, at total of 612 days until January 14, 2026. As a result, the 2024 General Assembly continued through 2025, so the legislature had parallel sessions.

The extended special session did not pass significant budget measures to deal with cutbacks in Federal funding during the first year of the second Trump administration. Republican Governor Youngkin had the power to veto such bills.

However, because the General Assembly was still meeting, Governor Youngkin could not make recess appointments to boards and commissions. In an unprecedented move, the Senate Privileges and Elections Committee - technically meeting in 2025 as part of the 2024 special session - rejected 22 of the governor's appointments to boards of several universities. The Republican Attorney General directed the appointees to continue meeting with the university boards until the state court system made a final ruling on their status.

Attorneys for the governor argued that the entire State Senate and House of Delegates had to act before a nomination was rejected, just as approval by both houses was required to confirm. The Virginia Supreme Court agreed with the state senators that approval by the Privileges and Elections Committee was the first step in the process, and rejection by that committee was sufficient to kill a nomination. Forcing a nomination to be considered by the House of Delegates after rejection in the State Senate would be a wase of time, what a justice called "an empty formality."9

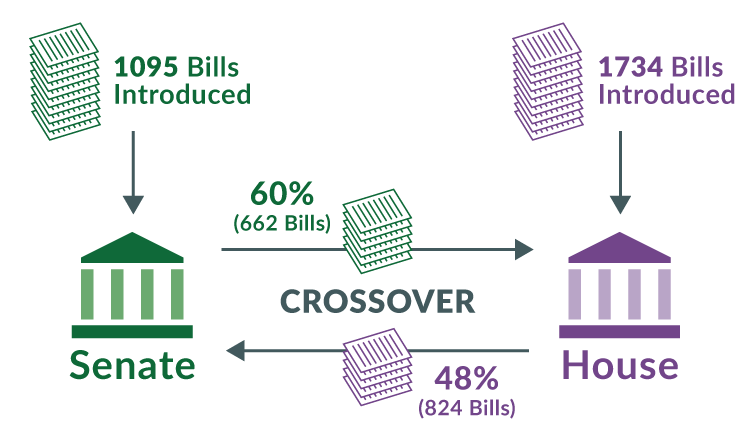

Most bills are debated and acted upon in subcommittees and committees. A small percentage get approved and reach the floor of the House of Delegates or State Senate. Those approved by one house then "cross over" to the other house for approval, revision, or rejection. If a bill is approved by both houses of the General Assembly, it must be signed by the governor unless the bill is a "joint resolution."

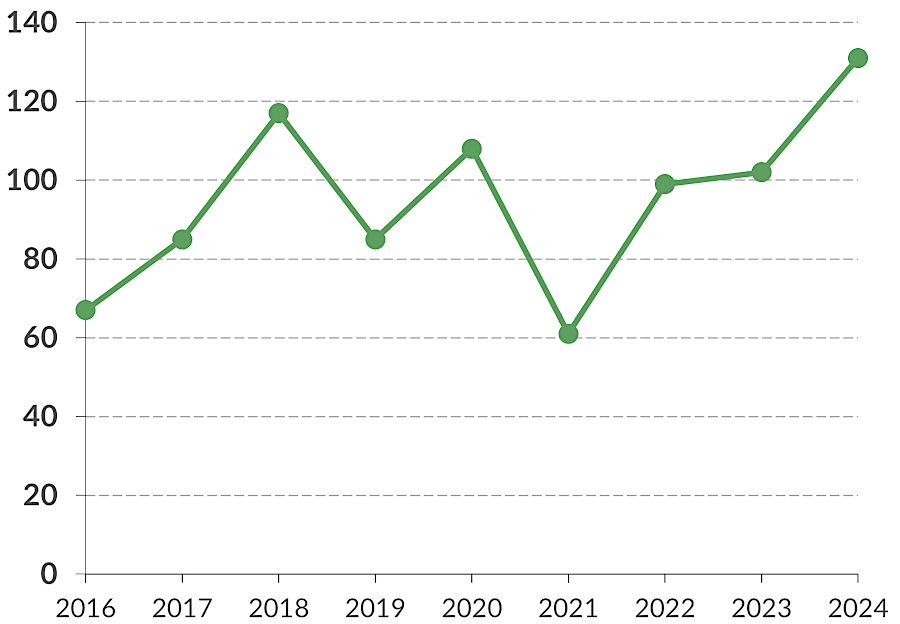

number of House and Senate bills killed after passing a committee and then being referred to appropriations committees, prior to crossover

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Surviving One Committee Only to Perish in the Money Committee

Most bills proposed by members never get to the governor for approval or veto because they are killed during the legislature's deliberative process. The Department of Planning and Budget provides a Fiscal Impact Statement on most proposed legislation expected to affect state expenditures. The statement assesses just expected costs or savings, without any evaluation of the policies affected by the bill. Other state agencies provide Fiscal Impact Statements on bills affecting their specific area of responsibility:

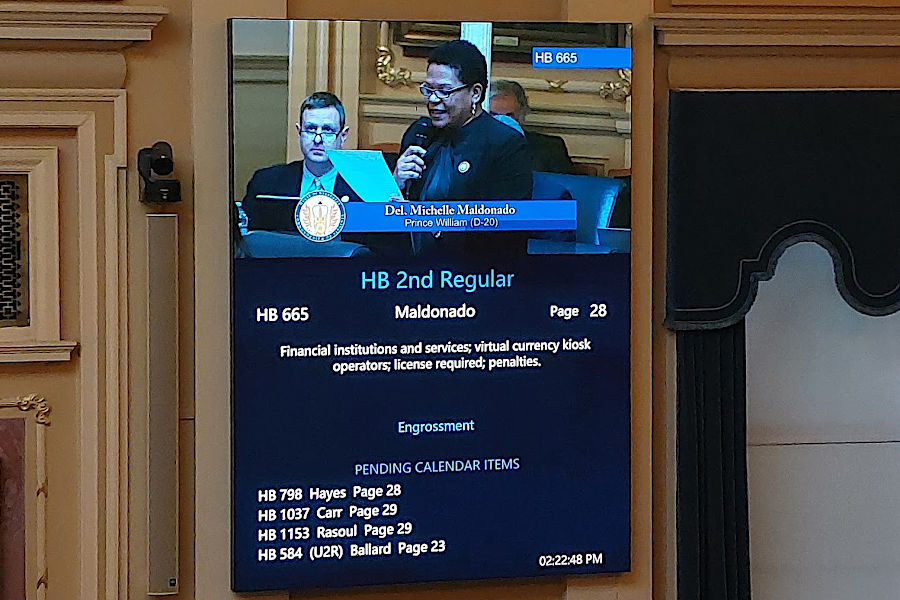

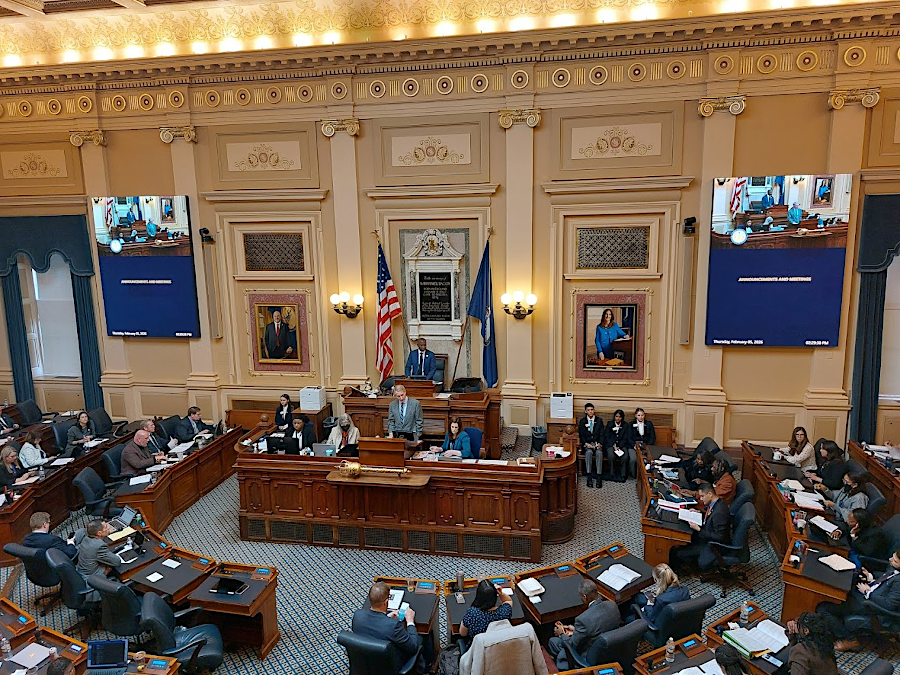

in the House Chamber at the State Capitol during a General Assembly session, delegates quickly summarize their bills before discussion and votes

No Fiscal Impact Statement is prepared for the governor's proposed budget submitted in even-numbered years, or for the "caboose" bill amending that budget in odd-numbered years. The departments have very little time to calculate fiscal impacts, and may simply state that the change could be done within the current appropriation.

The Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission must list $50,000 as an anticipated minimum cost to implement any bill that will increase the number of adult prisoners. Delegate Chip Woodrum of Roanoke championed the bill in 1993 that requires a minimum cost in the fiscal assessment of any legislation that would add inmates, such as the creation of a new felony.

The law requires the $50,000 minimum if impacts are unclear, and even today legislation that triggers a fiscal impact statement by the Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission is known as a "Woodrum bill." They must go through a second approval process in the Appropriations Committee of the House of Delegates, and in the Finance and Appropriations Committee of the State Senate. Those committees killed bills based on keeping taxes low, reducing the exposure of legislators to challengers who might claim that they were not tough on crime.

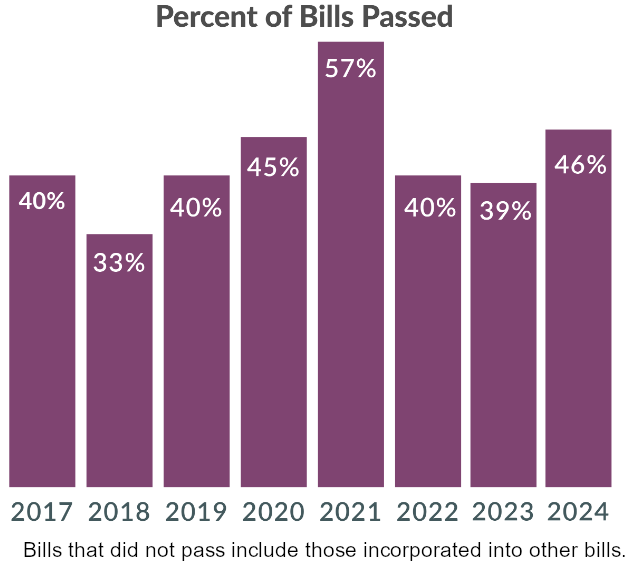

in most legislative sessions, it is rare for more than 50% of the introduced bills to pass both houses

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Pass or Fail? The Fate of 2024 Legislation

If a bill will create an expense large enough to require inclusion of a line item in the budget, then a majority of legislators are less likely to vote in favor. Bill sponsors may get their committee chairs to request a second evaluation by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC). That appeal process is not triggered often; in a typical General Assembly the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission might produce a Fiscal Impact Statement on only five bills. With additional time to assess a proposal, that state agency provides a different estimate of implementation costs about half the time.10

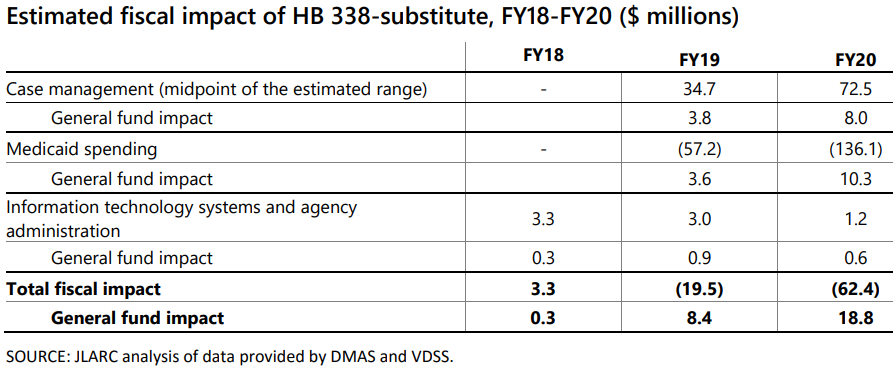

Expansion of Medicaid in 2018 to implement "Obamacare" was done through approval of the Appropriation Act, the state budget bill. The governor provided estimates of cost, but there was no Fiscal Impact Statement from the Department of Planning and Budget. A separate bill to require some Medicaid recipients to work or participate in community engagement activities for up to 20 hours per week was evaluated by the Department of Planning and Budget, and then again by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, to evaluate costs for case management and support as well as savings from reducing the number of individuals being enrolled.

After approval of the expansion of Medicaid in the 2018 General Assembly, the Department of Medical Assistance Services discovered that the entire program would cost about $460 million more than projected during the two-year budget cycle. The state had expanded the use of private long-term care companies to provide complex services needed by elderly and disabled Medicaid recipients, and miscalculated how much funding would be required to compensate those companies.

The extra costs were not for medical services for the new people enrolled by expansion of Medicaid. The Department of Medical Assistance Services still estimated that Medicaid expansion would save the state about $360 million over two years, and the surprise budget gap would have occurred whether or not Medicaid expansion had been approved.11

estimated fiscal impact of a state program overseeing requirement that Medicaid recipients seek work or provide community services

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Fiscal Impact Review HB 338-substitute (2018)

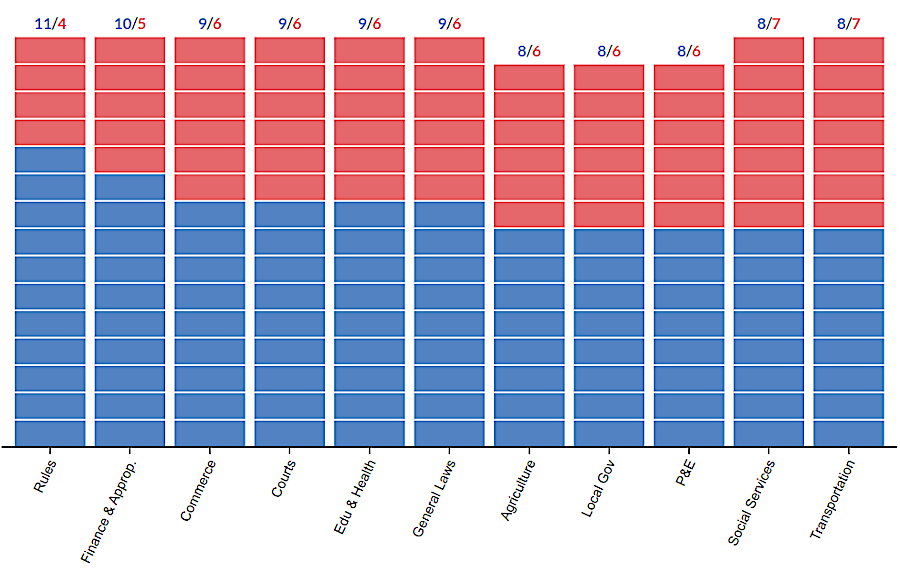

The State Senate has 11 standing committees. Senators with the most power typically serve on the Rules, Finance and Appropriations, and Commerce committees. In the State Senate, the caucus of each party decides which Republicans and which Democrats will serve on each committee, and then the whole State Senate votes at the start of each General Assembly to endorse those decisions. Unlike the House of Delegates, the party in control of the State Senate does not determine which individual members of the minority party will serve on different committees.

The clerk of the State Senate, not the Majority Leader, assigns proposed bills to committees based on their differing responsibilities. A objection to a bill assignment is resolved by the Rules Committee. Bills are often heard by two committees in sequence, especially if a proposal affects the "turf" of the Finance Committee in the House of Delegates or the Finance and Appropriations Committee in the State Senate.

end of the House of Delegates session on February 4, 2026

In 2024, referral of SB212 minimized the potential for a committee to kill a bill before it reached the full State Senate. SB212 proposed to legalize "skill games" which closely resemble slot machines. It was sent first to the Senate Committee on Commerce and Labor, where there was support for the proposed legislation. The Senate Rules called for bills involving gaming and wagering to be considered by the General Laws and Technology Committee, but the chair of that committee was not a supporter of the bill. The Senate Committee on Commerce and Labor chose to bypass the General Laws and Technology Committee and refer the bll directly to the Finance and Appropriations Committee.

The referral of the skills game legislation was not a partisan issue. Of the 10 state senators who voted to bypass the General Laws and Technology Committee, six were Republicans and four were Democrats.12

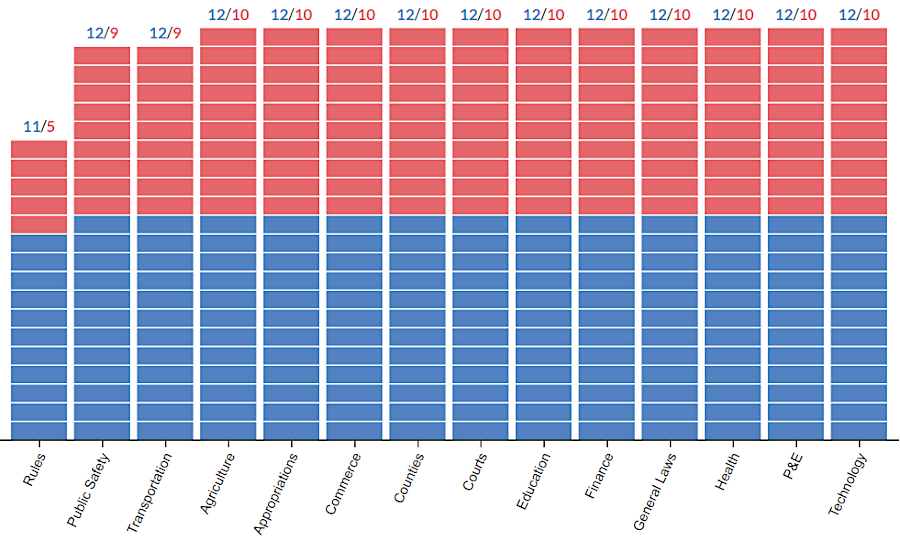

in 2024, with a 21-19 Democratic majority in the State Senate, Democratic appointees were over-represented on key committees such as Rules

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), 2024 Committee Party Split

The House of Delegates, with 100 rather than 40 members, has 14 standing committees. There too, the Appropriations, Rules, and Commerce committees are the most-prized assignments. The Speaker of the House serves as the House Rules Committee chair, and is the only delegate who may serve as chair or vice-chair on more than one committee .

Members of the General Assembly propose legislation before the start of each session. The legislator submits a draft to the Department of Legislative Services, which revises the language as needed so it is most appropriate for inclusion in the Code of Virginia. At times a legislators may propose a bill requested by a constituent to address an issue that is not a priority for that member of the General Assembly. Such bills are identified in the Legislative Information System by adding "by request" after the patron's name. Legislators also shape public policy by proposing amendments to the Governor's budget.

the State Senate, Virginia Supreme Court, Governor's Cabinet, and invited guests meet in the House of Delegates Chamber for the Governor's address at the opening session of the 2024 General Assembly

Source: Virginia House of Delegates Video Streaming, Regular Session (January 10, 2024)

Next to the Governor, the Speaker of the House of Delegates is the second-most influential elected official in Virginia.

The Speaker of the House assigns bills to whatever committee he/she desires. The Speaker determines the 22 members who will be appointed to each committee, including members of the minority party as well as members of the Speaker's own party, and who will serve as committee chair and vice-chair.

Appointments to key committees are not always consistent with the partisan balance in a chamber. In the 2024 State Senate, with a 21-19 Democratic majority, there were 10 Democrats and 5 Republicans appointed to the Finance Committee. After the House of Delegates and State Senate ended up with 50-50 splits between elected members, some committees in the two houses have been assigned members based largely on the partisan split percentage.

in 2024, with a 51-49 Democratic majority in the House of Delegates, most committees had 12 Democratic and 10 Republican members

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), 2024 Committee Party Split

The minority party can identify its preferences for which of its members should serve on different committees, but the Speaker makes the final decisions. He or she also appoints any independents, who typically caucus with either the Republicans or the Democrats, to one or more committees.

The rules of the House enable a Speaker to stack a committee with a majority of members known to oppose certain legislation, then assign a bill to that committee in order to kill it.

The Speaker can also use committee assignments to marginalize the effectiveness of members of the either political party. In 2020 the Democratic Speaker did not reappoint the Minority Leader to the Courts of Justice Committee, limiting his capacity to block her agenda for gun control and criminal justice reform.

In 2024 the Democratic Speaker did not appoint Del. Lee Ware, a known advocate for regulating public utilities, to the House Labor and Commerce Committee. Ware had served on that committee since 1997; he was a rare Republican skeptic of the policies proposed by Dominion Energy. There was speculation that the decision reflected the preference of the state's largest regulated utility, which had contributed $1.3 million to the Speaker since he was first elected in 2019.13

In an unusual pair of moves, the speaker in 2024 changed committee assignments in the middle of the session. Right at "crossover," when bills passed by the House of Delegates and the State Senate are sent to the other chamber, the Democratic Speaker removed the chair of the House Republican Caucus from the Rules Committee.

Speaker Don Scott also removed the ranking Republican from the House Appropriations Committee. Del. Barry Knight had chaired the committee in 2022 and 2023 when Republicans had a majority of members in the House of Delegates, and had a wealth on institutional knowledge and experience. The committee was considering the two year budget proposed by Gov. Youngkin.

The change was made without consulting the Republican leadership and was a surprise. Knight was moved to the Transportation Committee, and another delegate from Virginia Beach was shifted from it to the Appropriations Committee. The unexpected changes left the Hampton Roads region with equivalent representation, and did not alter the number of Republicans on the committee. However, Republicans in the House viewed the shift as partisan punishment. Observers predicted that a future Republican majority would exact retribution.

The Democrats retained and expanded their majority in the House of Delegates in the 2025 elections. In 2026, a Republican delegate from Bedford County refused the request of the subcommittee chair to stop speaking about his anti-abortion views, which the chair considered not relevant to a bill for the Board of Health to regulate violence prevention professionals. The Bedford County delegate declined to apologize for what was perceived as disrespect to the chair, after which Speaker Don Scott stripped him from all committee assignments. 14

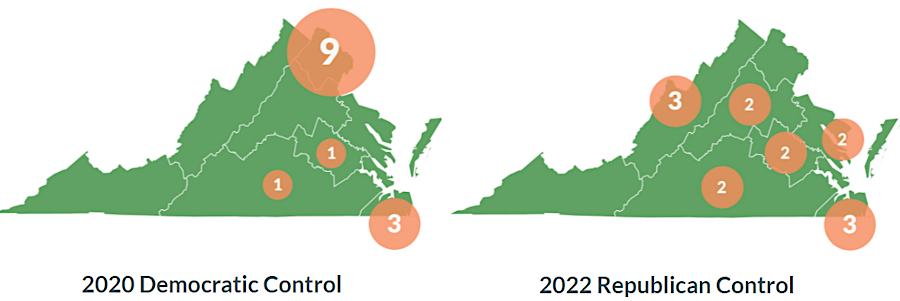

since 1998, partisan control of the House of Delegates has flipped between Republicans and Democrats (independents are orange)

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), House of Delegates Partisanship: 1978-2026

"Payback" can take a long time. In 2024, a Republican member of the House of Delegates introduced a bill that would severely restrict access to abortions.

There was a long-standing tradition that delegates could withdraw their proposed legislation after assessing it would not pass. and kill a bill before a vote. However, in 2024 Democrats saw the bill as an opportunity to force Republicans to go on record restricting a woman's right to choose, creating an opportunity for 2025 campaign ads highlighting the issue. The assumption was that a majority of Virginia voters supported reproductive rights, and on-the-record Republican votes in 2024 would yield Democratic victories in 2025 elections.

The maneuver was a duplication of what happened in 2008, when Republicans controlled the House of Delegates and refused to allow a patron to withdraw his bill to allow state agencies to engage in collective bargaining with labor unions. They had forced a vote by all 100 members in order to make Democrats vote against their union supporters, or energize voters in the next election who opposed increasing the power of labor unions.

In 2008, the unions told the Democrats to oppose the collective bargaining bill and they would ignore the vote. in 2024, almost all th Republicans also chose to oppose the bill limiting access to abortion, nullifying the attempt by the Democratic leadership to force an unpopular public stand on the issue.

Assessing the process of forcing a vote in 2024, a former Democratic Majority Leader commented:15

In 2017, Danica Roem flipped the 13th House District, defeating the Republican incumbent by highlighting her commitment to "fix" Route 28 traffic congestion. The Republican Speaker refused to assign her to the Transportation Committee, where she would have the greatest opportunity to act on her signature campaign issue. She was re-elected anyway in 2019, and after that election the Speaker of the House was a Democrat. She assigned Del. Roem to the Transportation Committee.

the Republican Speaker of the House of Delegates declined to appoint Del. Danica Roem to the Transportation Committee in 2018 and 2022

Source: The Derecho, Uhh, Danica, You Should Know Better

In 2022, Republicans were again in charge of the House of Delegates. The Speaker dropped Roem from the Transportation Committee. In 2023, she was elected to the State Senate and Democrats won control of that body. In 2024, State Senator Danica Roem was assigned to the Senate Transportation Committee.16

In 2022, after Republicans won control of the House of Delegates in the 2021 election, the Speaker appointed new committee chairs that were Republican delegates. In the previous 2020-2022 session when Democrats had the majority, 9 of the 14 committee chairs in the House of Delegates had been Democrats from Northern Virginia. In 2022-2024, no committee chairs were from that region. That discrepancy reflected the small number of Republican delegates from Northern Virginia compared to "downstate" and their lack of seniority.

In the 2022-2024 session the Speaker, House Majority Leader, and a Deputy House Majority Leader represented districts from west of the Blue Ridge. Of the 14 committee chairs, eight chosen by the Speaker had been elected from districts in rural areas. The partisan strength of Republicans in rural districts, and Democrats in urban districts, created a geographic shift in legislative leadership when power shifted between the political parties.

The lack of senior Democrats from rural areas affected leadership of the Senate Agriculture, Conservation and Natural Resources Committee and the House Agriculture, Chesapeake and Natural Resources Committee in the House of Delegates. In 2020-2020, both chairs represented districts in Fairfax County. In 2024-2026, the chairs represented districts in Fairfax and Arlington counties. No members from rural Southside Virginia were appointed in 2024 to the 15-member Senate Finance Committee.

the Republican Speaker of the House of Delegates appointed committee chairs in 2022 that reflected the geographical strength of the party outside of Northern Virginia

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Political Change, Cultural Shift

In both the State Senate and the House of Delegates, committee chairs have the authority to determine when a bill will be considered. Scheduling can be orchestrated to avoid votes when a large number of advocates attend a committee meeting, which can minimize the political impact of a "yes" or "no" vote by certain members. A committee chair can also decide never to bring up a bill for discussion or a vote, guaranteeing that it will not pass. Subcommittees in the House may kill legislation, but in the State Senate a subcommittee can only make a recommendation to the full committee for its action.17

The flood of proposed bills for each session can overwhelm the 140 part-time legislators. A patron may need to reintroduce a bill in multiple sessions of the General Assembly before members are familiar enough with an issue to vote in favor, rather than use different techniques to avoid making a clear decision.

Legislators elected for the first time in November will file bills in December for consideration by the upcoming General Assembly that starts meeting in January. New legislators have little opportunity to talk with stakeholders in state agencies and interest groups, or with fellow legislators, to explain the rationale behind their proposals. First-time legislators struggle to get bills passed in their first year in office and to establish a track record on which they can run for re-election at the end of their two-year term.18

A subcommittee or committee can postpone consideration of a bill by voting to "Pass Buy Indefinitely for the Day," but a decision to "Pass By Indefinitely" (PBI) or to "Strike" the bill kills consideration of the bill for the rest of the session. A "Lay on the Table" decision also halts discussion. If legislators do not want to upset an interest group by rejecting a bill outright, they have the options to "Report and Refer" or just "Refer" the bill to another committee for consideration. It is rare that a second committee will endorse a referred bill and "Report" it to the full House of Delegates or Senate.

A bill that gets approved by a full committee is then reported to the floor of the entire House of Delegates or Senate. A bill then must be approved by one of those two bodies before Crossover Day, when it is sent to the other body for rejection/amendment/approval there. Bills not approved by one house by Crossover Day will receive no further consideration in that session of the General Assembly, unless the governor incorporates some language in a proposed budget amendment.

in 2020, roughly half of the introduced bills survived to be considered by the other house after crossover

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Crossover 2020

Many bills passed by both the State Senate and House of Delegates including some different language. Leaders of each house appoint a small number of their members to a conference committee to adopt language that will be exactly the same, and then each house will vote on the bill with the compromise wording. Members of the conference committees, especially for the budget bills, are the most influential legislators in the General Assembly.

Occasionally, a conference committee will alter a bill in such a way that one of the houses will not approve the revised wording. In 2019, bills to prohibit drivers from using cell phones passed the State Senate and House of Delegates. Members of the conference committee revised the language so reading texts, using an app or typing would be banned, but drivers would be allowed to hold the phone in their hands while talking. The modification was not acceptable to legislators concerned about distracted driving, and the bill died that year.19

The assumption that televising meetings of the General Assembly will increase transparency of the legislative process is not fully accurate. A new member of the House of Delegates noted in 2020 that she still managed to meet with her peers outside of the spotlight:20

Chuck Colgan served in the State Senate between 1976-2016, and while on the Finance Committee earmarked funds for the George Mason University campus in Prince William County

The 2019 session of the General Assembly lasted 47 days. The legislators considered, sometimes quite cursorily, 2,362 bills. By one calculation, the two houses approved 950 bills. Resolutions do not require action by the governor, but most bills require the governor to sign, amend, or veto.

The Virginia Mercury noted:21

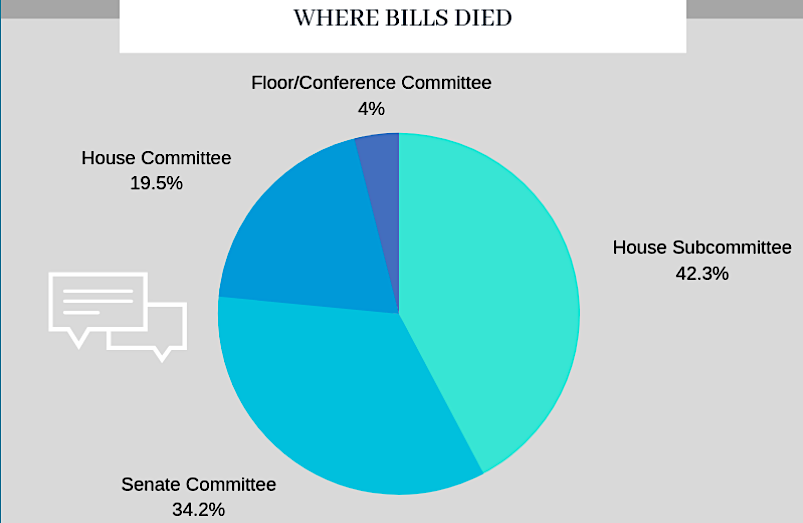

in 2019, as usual, most bills rejected by the House of Delegates died at the subcommittee level

Source: VaOurWay, A Look at the 2019 General Assembly (p.5)

Bills are printed after passage with the exact same language by both houses ("enrolled"), then signed by the Speaker of the House and the Lieutenant Governor (who presides over the State Senate) and delivered to the governor's office on the third floor of the State Capitol. If the governor does not want to sign or veto the bill, he can recommend one or more amendments to the General Assembly.

Article V, Section 6 of the state constitution requires the governor to sign, amend, or veto bills passed and presented to him more than seven days before General Assembly sessions end. A governor has 30 days to act on bills passed closer to adjournment.

A special "veto session" of the General Assembly is held automatically after the regular session ends, to deal with gubernatorial vetoes and amendments. Vetoes can be overridden by a two-thirds vote of the members present, in each house. If an amendment is approved by a majority in each house, the governor's proposed revision becomes law. If the amendment is rejected in at least one house, the governor has two choices - accept the original bill without the amendment, or veto the bill completely.

A third option is for the General Assembly to revise the original bill and alter the proposed amendment, then send the bill back to the governor.

Political bargaining is at the core of the decision process used by 140 legislators to make decisions. The checks and balances on power, created in the Constitution of Virginia, rarely allow one faction driven by political ideology or regional priorities to impose their will without compromise. A former Majority Leader in the House of Delegates used colorful language in 2020 to describe the process:22

when in session, members of the House of Delegates vote electronically from their desk

Relationships in the General Assembly are essential to getting bills passed and signed into law by the governor. Occasionally there is a trifecta where either Democrats or Republicans control both houses of the legislator and the office of governor, but most of the time there is a split between parties for one of the levers of power. For example, members of the House of Delegates seek co-sponsors from the other party in order to improve the potential for the State Senate also to approve the bill and for the governor to sign rather than veto it.

Building relationships in a part-time legislature requires time, and members with seniority members also gain leadership roles. At the start of the 2026 regular session, there were only five members in the 140-seat legislature who had been elected before 2000.

There had been a rapid turnover in the House of Delegates; over 20% of the members had been elected after 2019. When the new legislators elected in 2025 to draw lots for seniority, Lily Franklin (the member from the 41st District) ended up having the losing number and being designated as 100th in seniority. By the start of the session on January 14, 2026, she was 97th. Three members had resigned to serve in the administration of the new governor, and delegates elected after Franklin had less seniority.23

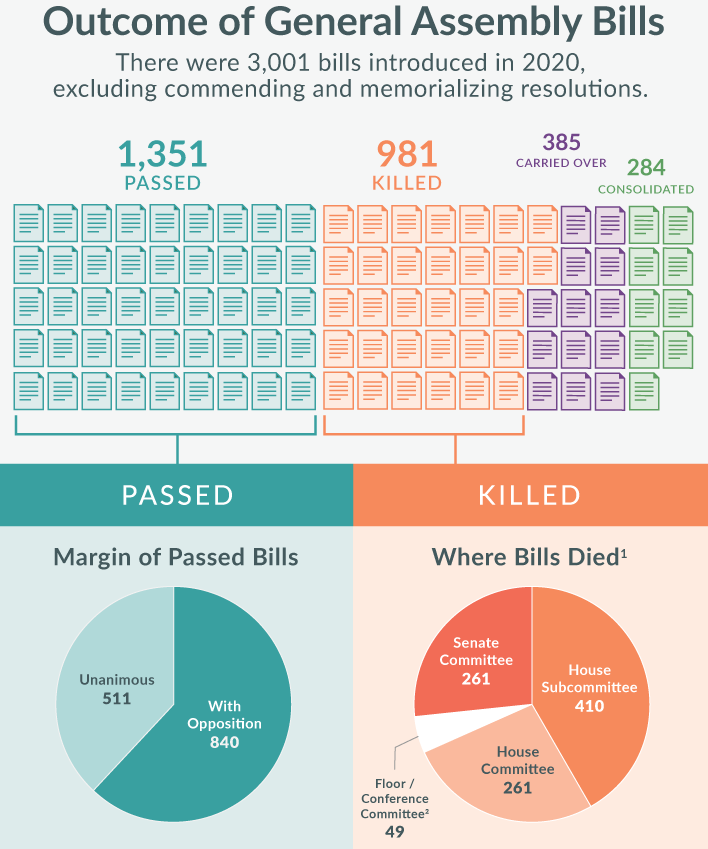

in 2020, 45% of the bills introduced were ultimately passed by the General Assembly

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Pass or Fail? The Fate of 2020 Legislation

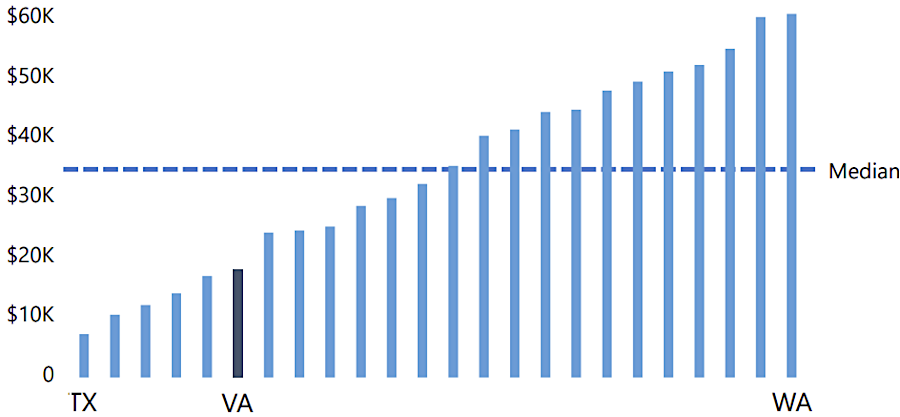

Between 1974-1980, salaries for state legislators were $5,475/year. That was increased to $8000, then increased again in 1984 to $11,000/year. The last time salaries were increased was in 1988, when they were raised to $18,000/year.

In 1991, Governor Wilder proposed a 2% reduction in salaries of state workers in order to balance the budget. The members of the House of Delegates approved a floor amendment to the budget, a rare event, and applied that 2% reduction to their salaries. Members of the State Senate did not alter their base pay. Since 1991, compensation for members of the House of Delegates ($17,640/year) has been 2% lower than for members of the State Senate ($18,000/year).

There was no cost of living adjustment tied to legislator compensation, and across-the-board increases for state workers have ot been applied to General Assembly members. Members did not increase their pay for nearly 40 years. Had pay been increased to match the 169% inflation between 1988-2026, legislators would be making almost $50,000/year.

Each of the 140 members receives the same payment for mileage and per diem to attend official meetings, plus an allowance for district office expenses. The state budget includes funding for the cost of office space in the General Assembly Building in Richmond and staff support there.

Though members are not full-time state employees, they receive health and retirement benefits. They are not required to contribute 5% of their salary in order to participate in the Virginia State Retirement System (VSRS). Retirement payments can be magnified for legislators who are recruited by a governor to serve in high-level positions within the Executive Branch, because the years of service as a legislator are counted towards calculating retirement benefits.

one perk of serving in the General Assembly is a state license plate with a low number

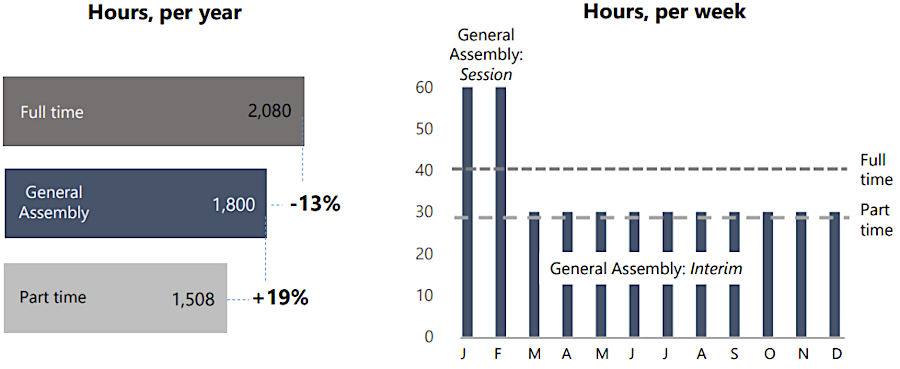

Legislators estimated in 2024 that they work on average 60 hours/week during the sessions of the General Assembly, which continue for 45 days in one year and 60 days the next. Between those annual sessions, delegates and state senators commit about 30 hours/week to their state jobs. Those 30 hours/week were consistent in every month when the legislature was not in session.

The amount of work compared to the compensation for a part-time job could make serving in the General Assembly a job suitable primarily for the rich, retired, or those relying upon a spouse's income. That may be a factor in helping legislators get re-elected, since most members must be employed in another job to pay the bills. One impact of the low pay and long hours: fewer candidates are economically able to challenge incumbents for the position.

When the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) was completing its 2024 salary review, one member said regarding balancing the workload between "regular" work and the General Assembly position:24

median hours required to serve as a member of the General Assembly in 2024

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Compensation: Virginia Senators and Delegates (SJR 17, 2024)

relative pay for serving in the Virginia General Assembly vs. other part-time legislatures

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Compensation: Virginia Senators and Delegates (SJR 17, 2024)

The National Conference of State Legislatures reported in 2025 that the average state legislator was paid $47,904/year. That was an 8% increase over 2024 salaries. New Mexico legislators were unpaid. In other states, salaries ranged from $100 in New Hampshire to $142,000 for serving full-time in New York.25

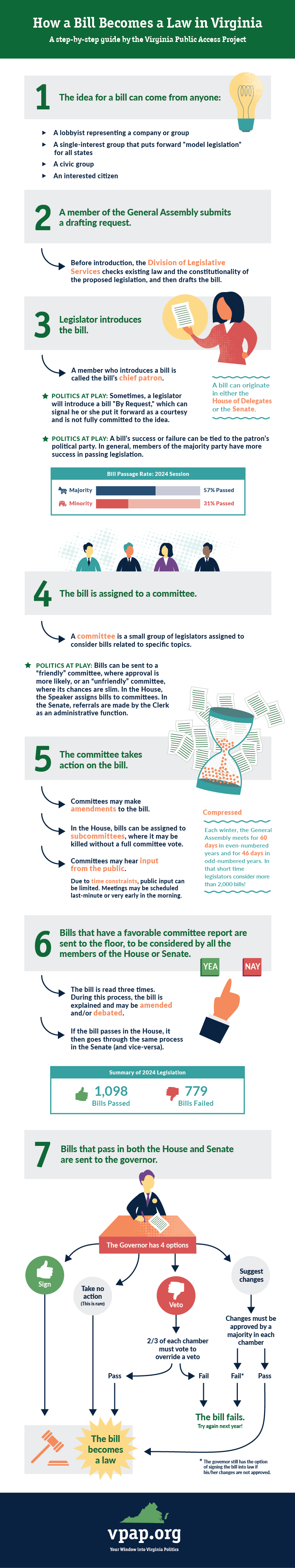

in the legislative process, the legislative branch (General Assembly) can over-rule objections by the executive branch (governor)

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), How a Bill Becomes a Law in Virginia

Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, home of the colonial governor - both the chief executive and head of colonial General Court, 1699-1775