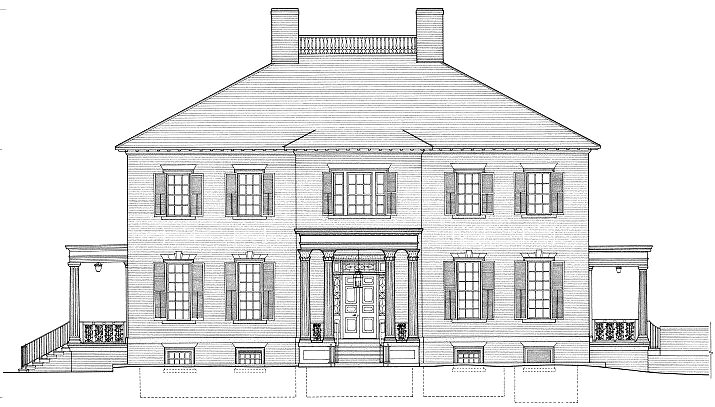

Governor Spotswood completed the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, and all royal governors or their deputies lived there until Lord Dunmore fled in 1775

Source: Wikipedia, Governor's Palace (Williamsburg, Virginia) (photo by Larry Pieniazek)

Governor Spotswood completed the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, and all royal governors or their deputies lived there until Lord Dunmore fled in 1775

Source: Wikipedia, Governor's Palace (Williamsburg, Virginia) (photo by Larry Pieniazek)

The Governor of Virginia is the most powerful single elected position in the state. He or she appoints agency heads and top leaders in the Executive Branch, and has veto authority over most bills passed by the General Assembly. In the legislature, 140 people share power. On the Supreme Court of Virginia, the Chief Justice has only one of seven votes.

After the American Revolution, however, the governor became more of a figurehead executive with little independent authority. The role of the state's chief executive has evolved since Virginia became a colony. Executive authority was not consolidated in Virginia until the 1902 constitution was revised in 1928.

The London Company chose the top administrator of the private corporation's business affairs in Virginia until the company charter was revoked in 1624. The First Charter issued by King James I in 1606 required creation of a council to manage affairs in the colony. From 1607-109 the leader of the council at Jamestown was called the "president."

The Virginia Company's leaders in London helped to craft the language of the Second Charter issued by the king in 1609, and it clearly empowered the company to appoint a "governor" in Virginia. The first governor of Virginia was Sir Thomas Gates, appointed in 1610.1

The Virginia Company's charter was revoked in 1624. When Virginia was a royal colony between 1624-1776, kings and queens in London appointed Virginia's governor. Between 1710-1768, the appointed governor's position was a sinecure in England. The governor hired a lieutenant governor to actually go to Virginia and administer the colony in the name of the royal monarch. The lieutenant governor was paid just a portion of the governor's salary.

Norborne Berkeley, Lord Botetourt, broke that pattern when he physically came to Virginia in 1768. Though he dissolved the House of Burgesses in 1769 after it responded to the Townsend Acts and asserted the exclusive right to impose taxes in Virginia, he remained popular. Botetourt died in the Governor's Palace in 1770, and the House of Burgesses commissioned a marble statue of him as a honor.

a bronze replica of the marble statue of Governor Botetourt stands outside the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary

Source: Wikipedia, Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt

The next and last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, was briefly popular after he arrived. However, he served when colonists decided that taxes and policies established in London were no longer acceptable. Complaints evolved into resistance, insurrection, and then open rebellion. Governor Dunmore fled Williamsburg to a British warship in June, 1775. After leading a failed military response to regain control of the colony, he eventually sailed out of the Chesapeake Bay to New York in August 1776.

The governors appointed by the monarch received instructions for setting policies from royal officials in London. He was advised within the colony by a Governor's Council (sometimes called the Council of State) composed of twelve of Virginia's most wealthy and prominent leaders.

Members of the Governor's Council were appointed for life and shaped the policy of multiple governors. Through the "advice" of the Governor's Council, the Virginia gentry maneuvered to implement policies that benefitted the wealthy landowners in the colony regarding tobacco inspection, land grants, trade with Native Americans, and other issues.

The Governor's Council, like the House of Burgesses, was a constraint on the ability of individual governors to implement policy. The members of the Governor's Council were typically selected by the governor in residence and reflected the social and economic power of different families in the colony, but appointments were technically made by the king or queen in London. Some appointments were made by the king/queen based on recommendations by London merchants rather than from recommendations made by the governor or his deputy serving in Virginia.

Even laws passed by the General Assembly, but opposed by key Virginia families, were repealed by the Privy Council in London. In the early 1700's, Governor Spotswood recognized that export of poor quality tobacco lowered the total value of the tobacco crop exported from Virginia, and that unfair interactions with Native American tribes threatened expansion of the colony due to unrest in the frontier contact zone.

Governor Spotswood succeeded in getting the General Assembly to regulate tobacco and Native American trade, only to see officials in London disallow the Tobacco Inspection Act and the Indian Trade Act. Throughout the colonial period, lobbying royal officials was an effective technique for undercutting the power of the appointed governor.2

The Governor and the dozen members on his council served as the "upper house" of the General Assembly after 1643. The office of governor included judicial as well as legislative and executive responsibilities. The General Court - the highest court in Virginia, hearing cases involving major issues and the death penalty for whites - consisted of the governor and the Governor's Council.

There were vacancies in Virginia after a governor died or failed to arrive on time. In those cases, the member on the Governor's Council who had served the longest became acting governor, and was called "President of the Council."3

In addition, royal appointee Governor Berkeley stepped aside between 1652-1660 during the English Civil War. Parliament sent a military force to Virginia and the General Assembly elected four governors. Once it was clear Charles II would be restored to the throne, Berkeley resumed his position as the royal governor.

colonial governors struggled with the General Assembly to implement royal guidance on growing, inspecting, and shipping tobacco

National Park Service, Tobacco and the Atlantic World - panel four of the Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network exhibit

Implementing royal policy transmitted from London required cooperation from the colonists in Virginia, since the colonial leaders controlled much of the wealth and led the militia. It was rare for royal troops to be positioned in Virginia, other than a guardship in Hampton Roads to protect against pirates and foreign raids, and most colonial revenue was controlled by the House of Burgesses or local governments.

The power of the governor varied based on personalities as well as economic/political conditions in England and Virginia, but the gentry serving in the House of Burgesses and on the Governor's Council prevented the governor from governing through edicts. In 1635, Governor John Harvey was "thrust out," forced by the leading colonists serving on his Council to leave Virginia and sail back to London.4

Governor William Berkeley was the longest-serving governor of Virginia, in that role for 27 years. He was in office from 1642-1677, with a gap between 1652-1660 during the English Civil War. Berkeley exercised his powers as governor to the fullest extent, gaining substantial wealth for himself in the process. His Green Spring mansion house was the center of political activity and described as "the finest seat in America & the only tollerable place for a Govenour...."5

no governor has served in office in Virginia longer than William Berkeley (27 years, counting his two terms)

Source: Library of Virginia, Sir William Berkeley

Colonial governors determined when the General Assembly would meet; elections were not scheduled on a regular basis. Gov. Berkeley evidently liked the burgesses who had been elected in 1661 after he was restored to office. He blocked new elections for the next 15 years, simply adjourning ("proroguing") the General Assembly after a session and recalling the same burgesses rather than authorizing elections colony-wide for new representatives.

Ending the "Long Assembly" with new elections in 1676 did not prevent Bacon's Rebellion. Berkeley faced down one threat when Nathaniel Bacon brought his forces to the statehouse, but was soon forced to flee Jamestown to safety on the Eastern Shore. Once the rebellion was crushed and Berkeley restored to office, he demonstrated the full range of executive authority in his retribution. He seized property and hanged 23 rebels, including the former governor of North Carolina (William Drummond).

Between 1710-1768, the appointed governor stayed in England. He allocated a portion of the office's income to pay someone else to serve as governor in Virginia. Lieutenant Governors did all the work, but received only a portion of the position's salary. The royal appointee, who stayed in England, kept the rest.

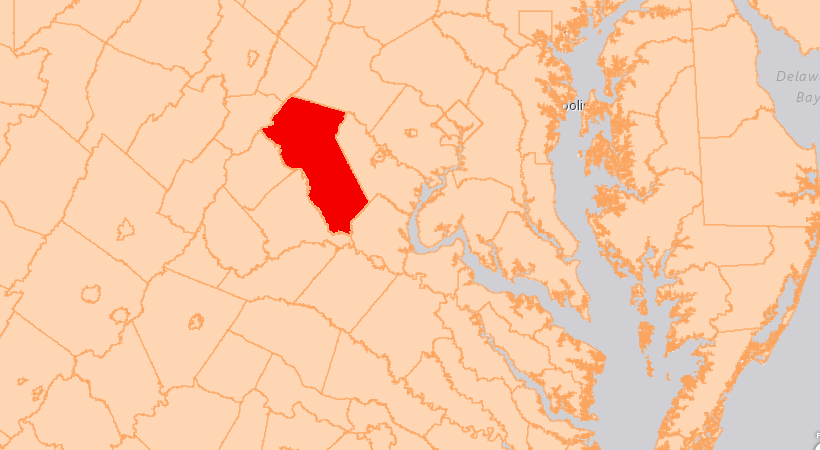

Fauquier County is named after Francis Fauquier, the last Lieutenant Governor to serve in colonial Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The House of Burgesses led the revolution against the colonial governors. When Lord Botetourt dissolved the legislature in 1769, the burgesses reassembled down the street in the Raleigh Tavern and adopted the Non-Importation Act.

In 1774, after Lord Dunmore dissolved the legislature when it showed support for the rebellious port of Boston, the burgesses once again ignored the royal requirement that the governor had to call for a meeting of the representative assembly and that the governor could force an end such meetings. That 1774 meeting, also in the Raleigh Tavern, was the first of five Virginia Conventions in 1774-76. They organized military resistance and maintained government services until independence, when a new General Assembly was created with a House of Delegates and State Senate.

During the colonial period, the Virginia gentry had relied upon the House of Burgesses to block actions of the royal governor and to implement policies preferred by the Tidewater planters. In 1776, at the start of the American Revolution, the General Assembly wrote a constitution that made the legislature the dominant branch of government.

The legislators who created that first Virginia constitution took advantage of the change in government to minimize the authority granted to the office of governor. The 1776 constitution separated the executive branch from the legislative and judicial branches. The position of governor was stripped of the old colonial authority to call and dissolve the legislature, and the governor was not empowered to veto bills passed by the General Assembly.

The governor retained the authority to appoint the judges who served on the county courts (no local officials were elected at the time), but had to share executive authority with an eight-person Council of State. The council was chosen by the General Assembly, just as the governor was elected by the legislature. The executive branch was separate from the legislative branch, but power of those two branches was unbalanced by design. The rebellious delegates wanted to create no opportunity for establishing a new monarchy in Virginia:6

After declaring independence from Great Britain and proclaiming the new constitution to be in effect, the General Assembly elected Patrick Henry as the first governor of the new Commonwealth of Virginia.

Raleigh Tavern served as the alternative for the House of Burgesses to meeting in the Capitol, when governors Botetourt and Dunmore dissolved the colonial legislature

For the 76 years between the establishment of Virginia as an independent state and the adoption of the 1851 constitution, the General Assembly chose the governor. There was no Lieutenant Governor position in the system of government until the 1851 constitution, which shifted responsibility for electing the governor from the legislature to the voters. That created the need for a new succession sequence in case the governor died or resigned, other than election by the legislature.

Patrick Henry was chosen to be Virginia's governor in 1776 in part because his opponents desired to see him isolated in that office rather than dominating the legislature. He was "pushed upstairs" to reduce Henry's ability to shape policy through speeches in the new General Assembly.

Henry was the first post-colonial governor to live in the Governor's Palace, between 1776-79. He was replaced by Thomas Jefferson, the last to live there.

The state capital was moved to Richmond in 1780, and the "Governor's Palace" erected by Governor Alexander Spotswood burned to the ground in 1781. Colonial Williamsburg built a replacement structure during the Great Depression, and the reconstructed Governor's Palace is a popular tourist destination today.

Between 1776-1830, under the provisions of the state's first constitution, governors served one-year terms with a maximum limit of three consecutive terms.

One, William Fleming, served just eight days. Thomas Jefferson's term expired when the General Assembly had been forced to flee from Richmond and then Charlottesville by General Cornwallis' British army. Between June 4-12, 1781, Fleming acted as governor until the legislature assembled and selected Thomas Nelson.

Fleming is one of only two Virginia governors to serve after 1776 who was not born in the United States. Fleming was born in Jedburgh, Scotland. Westmoreland Davis, elected in 1917, was born in Paris while his parents were on their annual summer holiday. However, he later claimed he was born on the ship traveling back across the Atlantic Ocean.

The General Assembly "fired" Governor Henry Lee III (Light-Horse Harry Lee) in 1794, after he had been elected to his third consecutive term as governor. During that term Governor Lee accepted President George Washington's appointment as a major general, in order to lead the US Army force to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. As described by the Encyclopedia Virginia:7

The 1776 constitution required the governor to obtain approval for all executive actions by the Council of State, which was also called at times the Privy Council and the Executive Council. If the governor died in office, the longest-serving member of the Council of State acted as governor until the General Assembly could elect a replacement. When Governor George William Smith died in the Richmond Theater fire in 1811, Peyton Randolph assumed the responsibility to act in the role of governor. The General Assembly happened to be in session, and was able to elect James Barbour as governor just nine days later.

The requirement for a governor to get all actions approved by the Council of State was retained in the 1830 constitution. That created a problem for Governor John Floyd in August 1831, when he received word of a rebellion by enslaved people in Southampton County led by Nat Turner. None of the members of the Council of State happened to be in Richmond. The governor could not call out the militia to help suppress the insurrection until one member returned, at which point a cursory consultation could be completed. Only then could Gov. Floyd send militia forces to Southampton County.8

The 1830 constitution established a fixed three-year term of office, and governors could not be re-elected immediately after completing a term. The 1851 constitution changed the governor's term of office to four years and continued the ban on immediate re-election. The Virginia constitution has been replaced and amended several times since 1851, but the four-year governor's term and the ban on consecutive elections have not been altered in those revisions. In contrast, there are no limits on the number of consecutive terms that one person can serve as Lieutenant Governor or Attorney General.

The 1851 constitution allowed the voters, rather than the General Assembly, to elect the governor. The legislative districts at the time were drawn so people east of the Blue Ridge would always control the General Assembly, no matter how much the population expanded west of the mountains. Reducing the General Assembly's role in choosing the governor gave more political weight to people living between the Blue Ridge and the Ohio River.

Governor Joseph Johnson, who served between 1852-56, was the first Virginia governor to be elected directly by the people. It was the first election in which almost all white males over 21 could choose the top leader of Virginia, and it occurred 244 years after English colonization began at Jamestown.

Governor Johnson was the only person ever elected governor from a western county that ended up becoming part of West Virginia. He was also the only governor elected twice to serve the very same term.

Johnson had been chair of the constitutional convention in 1850-51 which proposed direct election of governors. In March 1851, before the new constitution was ratified by the voters, the General Assembly elected him to a three-year term which would start on January 1, 1852.

In the Fall of 1851, he ran for governor as the nominee of the Democratic Party. That vote was held in anticipation of the new constitution being ratified by the voters during the same election. Joseph Johnson assumed office on January 1, 1852 based on the General Assembly choosing him as governor. On January 16, a day after the direct election votes were officially counted, he became governor based on winning the race via popular election. He was the first governor to serve for four consecutive years, and left office on January 1, 1856.9

since 1813, Virginia's governors have occupied the same structure - except in the Civil War, when the state had two governors simultaneously

Source: Library of Congress, Governor's Mansion, Capitol Square, Richmond

In the colonial era after Virginia became a royal colony, multiple governors had been appointed by the English monarch to serve a second term. Sir Francis Wyatt was the first governor appointed by the king in 1624, and he served for two years. He was appointed governor again in 1639 and served for three years. In the gap between those terms, Sir John Harvey was governor from 1630-1635 and, after being temporarily "thrust out," between 1637-1639.

Sir William Berkeley also experienced an involuntary gap, due to the English Civil War, between his terms in 1642-1652 and 1660-1677. Berkeley is Virginia's longest-serving governor to live in Virginia. Berkeley had 27 years in office; next closest was Sir William Gooch with 22 years. The Earl of Orkney was technically governor for 27 years between 1710-1737, but he stayed in England the entire time and arranged for three lieutenant governors to represent the crown in Williamsburg.

Francis Nicholson served as the lieutenant governor in Virginia from 1690-1692, then as full governor from 1698-1705.

Since 1851, Virginia has elected only one governor to serve a second term - or elected three governors to second terms, depending upon how you choose to count. William Smith, Francis Pierpont, and Mills Godwin can claim to have been elected twice.

There is no question that Governor Mills Godwin served two terms. He was first elected in 1965 and served between 1966-70. After a gap of four years out of office, and a switch from the Democratic to Republican parties, he was elected a second time and served a full second term between 1974-78.

Term limits in the state constitution since 1851 blocked Gov. Mills Godwin from being eligible for re-election to a second term in 1969 or in 1977. After Kentucky changed its constitution in 1992, Virginia became the last state to prohibit governors from serving two consecutive terms. Terry McAuliffe tried for a second term in 2021, after serving from 2013-17 and then sitting out four years. However, the former governor was defeated in the 2021 election.

The one-term limit makes a governor a "lame duck" the moment he completes the oath of office on the second Wednesday in January. In contrast, members of the General Assembly may serve as many as 40 years. The legislators can accumulate expertise, connections, and political power that will last far longer than the term of one governor.

The relative significance of the legislative and executive branches is reflected by the ceremony of a governor's inauguration. The 1851 state constitution set January 1 as inauguration day. That was revised in the 1902 state constitution to February 1, changed in the 1928 constitutional amendments to the third Wednesday in January, then revised for the last time in 1958 to the Saturday after the second Wednesday in the January after the election.

Since 1914, inauguration ceremonies have been public spectacles held on the north or south side of the Capitol. The exeception was the inauguaration in 2006 of Governor Tim Kaine. That Capitol in Richmond was under major construction, so Kaine's event was held in Williamsburg.

The inauguration of the leader of Virginia's Executive Brabnch is an official session of the General Assembly, the state's legislature. The presiding officer at a governor's inauguration is the Speaker of the House of Delegates. The process begins with a joint meeting of the General Assembly in the chamber of the House of Delegates, before moving outside for the swearing-in ceremonies and speeches.

An experienced legislator summed up the power of the General Assembly by saying:10

The 1861-65 Civil War created the unique period when Virginia had two governors simultaneously. If you consider both the Confederate and Unionist governments of Virginia to have been legitimate during the Civil War, then both Gov. William "Extra Billy" Smith and Gov. Francis Pierpont served portions of their second terms in the 1860's.

John Letcher and William "Extra Billy" Smith were the two governors of Confederate-allied Virginia. John Letcher was elected governor in 1859, and was in office when Virginia seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America. Letcher's predecessor, Henry Wise, ignored the fact that he was no longer governor and, in April 1861, organized the seizure of the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and the navy yard in Portsmouth. Being an official governor does not guarantee you will carry all the powers of that office, at least in times of war.

Gov. John Letcher, from Rockbridge County, served as governor between 1860-64 when Virginia seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy

Source: Library of Virginia, John Letcher (1813-1884)

In 1863, in the middle of the Civil War, William "Extra Billy" Smith was elected governor of Confederate Virginia for the second time. Smith had been elected governor for the first time by the General Assembly in 1845, and had completed his 3-year term between 1846-49.

His nickname reflected his ability to create additional routes for mail delivery, and thus additional fees, when he had contracts to deliver the US Mail - not his election to an extra term as governor. He served as governor for the ever-shrinking portion of Virginia under Confederate control into 1865.

In 1863, he was elected by the voters in the Confederate portion of Virginia to serve a 4-year term. Smith did not complete that second term; he resigned formally in May, 1865 after the Confederate armies had surrendered.11

In 1861, after Virginia seceded and joined the Confederacy, those who supported staying in the Union formed the Restored Government of Virginia. A convention in Wheeling elected Francis Pierpont to be the governor of the Restored Government of Virginia.

Governor Francis Pierpont served as Unionist governor from 1861-1868

Source: Campfire and Battlefield - An Illustrated History of the Campaigns and Conflicts of the Great Civil War, Francis H. Pierpont

When West Virginia became a separate state in July, 1863 and Wheeling was no longer located in Virginia, Pierpont moved the governor's office to Alexandria. Once Gov. Pierpont moved to Alexandria, he left behind in West Virginia most of the voters who had chosen him. His authority was ignored in all areas occupied by the Confederates. Many Union officers in many of the occupied areas, primarily Alexandria, Fairfax, Loudoun, Accomack, Northampton, and Norfolk, also ignored the powers of the civilian government.

Pierpont was unopposed in the May 28, 1863 election. He was re-elected to a four-year term, but ended up serving almost an extra year longer until April 4, 1868.

After the Federal army captured Richmond in 1865, Governor Pierpont moved to his third state capital. He served as Provisional Governor of Virginia during the first years of Reconstruction, even after Virginia lost its status as a state and became Military District One. In 1868, General John Schofield forced Pierpont out of office and appointed Henry H. Wells as governor. Governor Wells served until Virginia voters were allowed to elect a new governor in 1869.

Wells won the Republican Party nomination for governor. However, the Republican convention also nominated an African-American physician, Joseph D. Harris, for lieutenant governor. Opponents of Wells who lacked the ability to block his nomination may have created that ticket to get him defeated. In the July 6, 1869 election, held on the same day that Virginia ratified a new state constitution that met the requirements for the state to be readmitted into the Union, Gilbert C. Walker defeated Wells by a 119,535-101,204 vote.

A gubernatorial election had been planned for 1868, not 1869. Resistance to provisions in the constitution drafted in 1868 delayed the election. As a result of that delay, Virginia still elects its Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General one year after the presidential election.12

Confederate governors occupied the mansion in Richmond, while Governor's Pierpont's office (right) was at 415 Prince Street in Alexandria

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Virginia's Executive Mansion (left image)

In 1849, 70 years after the capital moved to Richmond, the General Assembly gave the governor his own office on the third floor of the Capitol. Today, the portraits of the most recent 16 Virginia governors adorn the walls on that floor, including two portraits of Gov. Godwin to reflect his two separate terms. The location, above the second-floor chambers of the House of Delegates and State Senate, is reflected in the current state constitution (emphasis added):13

Whenever the state constitution was replaced or revised substantially since 1830, the authority of the governor has been increased from the weak position created in 1776. In 1830, terms were extended from one year to three. In 1851, terms were extended to four years and the governor's election was shifted from the General Assembly to the voters.

In 1864, the Restored Government of Virginia added a provision for the governor to nominate judges for election by the General Assembly, an authority which in later constitutional revisions was lost and then regained by the office. In 1870, the governor gained the right to veto bills passed in the legislature. The 1902 constitution gave the position authority for line item vetoes in appropriation bills.14

The most significant shift in power to the governor's office came in 1928, after advocacy by Governor Harry Byrd. In that revision of the state constitution, the next governor gained control over many of the independent state agencies. When voters approved amendments to the state constitution in 1928, they authorized the "short ballot" and eliminated five statewide elective positions - Secretary of the Commonwealth, State Treasurer, Auditor of Public Accounts, Superintendent of Public Instruction, and Commissioner of Agriculture and Immigration.

Byrd had sought to restructure the executive branch to operate more like a business, with the governor operating as the chief executive. When he took office, financial operations were fragmented. There was no statewide compilation of obligations or payments, and the governor's appointees were responsible for only 42% of state expenditures.

Byrd argued successfully that centralizing accountability would reduce waste, increase efficiency, and create a government that was more responsible to voter priorities as reflected in the election of the governor. Main opposition to Byrd's proposal to centrail Executive Branch authority came from the Ku Klux Klan. It objected to the recent election of a Catholic as State Treasurer. The Klan, composed of religious as well as racist bigots, anticipated defeating the incumbent in the next election rather than allowing the governor to appoint him.15

Governors make about 900 appointments each year to fill positions on about 300 public commissions and boards, some of which are advisory and some of which oversee state agencies. Governors can also create advisory groups on their own initiative, but those private groups are not "official" state organizations.

Many terms of appointees to official boards and commissions are fixed and do not expire when a new governor takes office. In the course of a four-year term, a governor gradually gets the opportunity to replace all of the appointees.

Govrernors may fire appointees, including those appointed by a previous governor whose terms have not expired. However, new appointees must be confirmed by the General Assembly. A joint eight-person committee (five members from the House of Delegates, three from the Senate Senate) review resumes before confirmation votes, often looking for financial conflicts of interest. Governor Northam made 2,941 appointments, and the General Assembly confirmed all but 10 of them.

If the General Assembly is in session, the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections rather than the joint committee votes on conformations before sending them to the entire State Senate for action. In 2025, it rejected 17 of Governor Youngkin's appointments to boards overseeing state colleges and universities. The governor claimed his appointees could continue to vote as board members until the entire General Assembly took final action, leading to a lawsuit to clarify the issue.

The heads of some state agencies are chosen by the governing boards which oversee those agencies, not hired by the governor. Governors have the authority to fire their direct appointees, but not the authority to fire the executives hired by those governing boards. That requires appointing new members to governing boards - or simply applying political pressure to force resignations. Soon after being elected in 1993, George Allen demanded that 450 of the top state officials must submit their resignations. The maneuver became known as the "Knife before Christmas."

In 2025, the Federal government pressured the president of the University of Virginia until he resigned. The Trump Administration threatened to cut off Federal funding to the university. Only the Board of Visitors of the University could fire the president, but he chose to quit. The university faculty then approved a resolution of no confidence in the Board of Visitors "for not protecting the University and its president from outside interference," but made no mention of the governor.16

Virginia governors have line item veto authority for the budget bill, as well as the power to propose specific amendments to language in other legislation. Governor Youngkin, a Republican, demonstrated in 2024 that use of Executive Branch authority could overturn policies adopted by a legislature controlled by the Democratic Party.

Democratic leaders in the General Assembly complained that Governor Youngkin was "overreaching and authoritarian," as he directed appointed members of the Virginia Air Pollution Control Board and other regulatory boards to bypass legislative direction on climate and energy policies. According to the Democrats, the actions were designed primarily to attract Republican donors to support a future race by Glenn Youngkin for national office.

Lawsuits filed by Democrats to force compliance with what Governor Youngkin determined were discretionary guidance rather than legislative mandates would not be settled until after the end of Youngkin's term. The frustrated Speaker of the House of Delegates stated finally that there was one final solution to the legislative-executive dispute regarding the checks and balances on Executive Branch power, a repeat of Democratic success in gaining control of the State Senate in the 2023 election:17

After more changes in the constitution in 1980 and 1994, a special "veto session" is scheduled each year on the sixth Wednesday after the adjournment of the regular session of the General Assembly. That guarantees the legislators will have an opportunity to react to the governor's vetoes and proposed amendments to legislation, before the next regular session of the General Assembly starts the following January.

The governor lives in the Executive Mansion, but has offices in other buildings. The main offices for the governor and his staff, plus Cabinet secretaries, moved to the Patrick Henry Building in 2005 after the former home of the Virginia State Library and Supreme Court of Virginia was renovated.

Control over that space has been contentious. In 2014, the Capitol Police unlocked the office doors and allowed the clerk of the House of Delegates to physically deliver a copy of the state budget. That delivery initiated the 7-day clock for the governor to act on the budget, and was part of the partisan bickering between the Republican-controlled House of Delegates and the Democratic governor.

The governor's office described the event as a breach of security and officially notified the Capitol Police that the governor's office was off-limits. However, the Capitol Police work for the General Assembly and do not report to the governor.

Unlike the Virginia State Police, the Capitol Police are not part of the Executive Branch. The decision to separate the executive, legislative, and judicial branches in the 1776 Constitution created a new form of government, but the tension between governors and legislatures goes back to the beginnings of colonial Virginia.18

The political parties were scrambled after the Civil War, but the election of former Confederate General Fitzhugh Lee in 1885 as governor started the dominance of the Democratic Party in Virginia. All 21 governors elected between 1885-1965 were Democrats, until Republican Linwood Holton won the office in 1969.19

Some Lieutenant Governors have run for governor and been elected to full 4-year terms, but no Lieutenant Governor has become governor due to the death of the incumbent governor. The last Virginia governor to die during his term in office was George William Smith in 1811, before the office of Lieutenant Governor was created in the 1851 constitution.

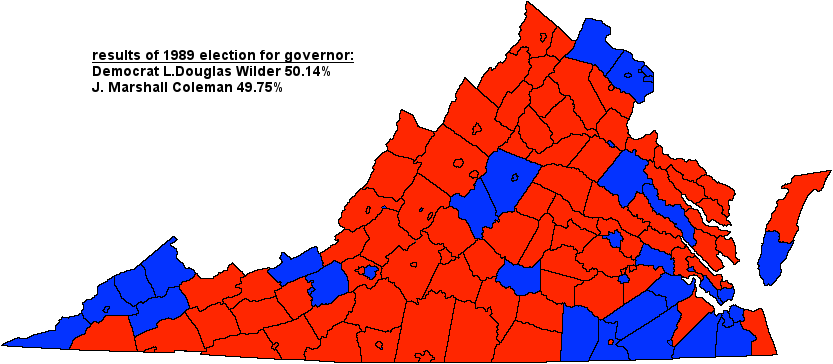

In 1989, Virginia became the first state to elect a black man, Douglas Wilder, as governor. (P. B. S. Pinchback had been appointed as governor of Louisiana in 1868.) Voters in Richmond had elected Wilder as a State Senator in 1969, a "first" since Reconstruction. His election as Lieutenant Governor in 1985 broke the color barrier for election to a statewide office in Virginia.

Douglas Wilder earned support from traditional Democratic leaders during his service in the State Senate, then won the nomination for Lieutenant Governor after rivals concluded that challenging Wilder would antagonize the African-American voters and cost them victory in the general election.

He campaigned initially in southwest Virginia and rural areas, gaining valuable publicity by appearing in person at places where segregation had been common. Key traditional Democratic leaders endorsed him, emphasizing his military career (Wilder won the Bronze Star in Korea) and his status as a Democratic candidate rather than as a man of color.

Wilder won election as Lieutenant Governor in 1985 by 52-48%. He won the governor's race in 1989 by 50.19%-49.81%, and the race was not certified until after a recount.

In 1990, Wilder was sworn in by fellow Richmonder and Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, who had been chairman of the Richmond School Board during "massive resistance" and had opposed closing public schools to maintain segregation of the races. During preparations for Wilder's inauguration, the Newport News Daily Press interviewed a black businessman in Richmond and recorded his prophetic statement:20

in 1990, Governor Wilder was sworn in as governor on the south steps of the State Capitol (Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, on right, administered the oath)

Source: Library of Virginia, Douglas Wilder Was Inaugurated Governor of Virginia, January 13, 1990

No Virginia governor has been forced out of office since William Smith and Francis Pierpont in the 1860's. In 2013, Gov. Robert McDonnell was accused of corruption, trading his influence in exchange for gifts and funding from the owner of a company trying to create a drug from tobacco. Near the very end of his term, McDonnell declined an offer from Federal prosecutors to resign in exchange for a lenient sentence and he finished his four years in office in January, 2014.

That same year the governor and his wife were both convicted in Federal court and later sentenced to jail. The Richmond Style Weekly wryly noted that the only Virginia governor to be convicted of corruption included in his official portrait the statue of George Washington next to the state capitol building:21

Before McDonnell's term, the Virginia State Penitentiary (with the electric chair for executions) had moved to the Greensville Correctional Center. Gov. McDonnell and his wife were convicted in a Federal court and could have been incarcerated in a Federal prison, had the conviction not been overturned by the US Supreme Court. Even if the state penitentiary was still located in downtown Richmond, they never would have been incarcerated in a state prison.

Only five offices in Virginia are elected through statewide votes - Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, plus the two Senators who serve in the US Congress. The Republican and Democratic parties nominate slates for the offices of Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, but Virginia voters regularly "split their tickets" and elect members of different parties to those three offices.

The Lieutenant Governor has the constitutional responsibility to preside over the State Senate. On the rare occasions that there is a tie vote in the State Senate, the Lieutenant Governor gets to break the tie except for budget-related bills. The Lieutenant Governor may choose to vote in opposition to the governor's preference; even if they belong to the same political party, they may be rivals.

In the race for governor, the election district is the entire state. Every vote from every part of the state has equal value; the total popular vote determines the winner.

Serving a single area does not appear to be a stepping stone to being elected Governor. As of 2023, the last sitting mayor to win a race for Governor was John Garland Pollard of Williamsburg in 1929. It helped that he had served previously in statewide office, as Attorney General.

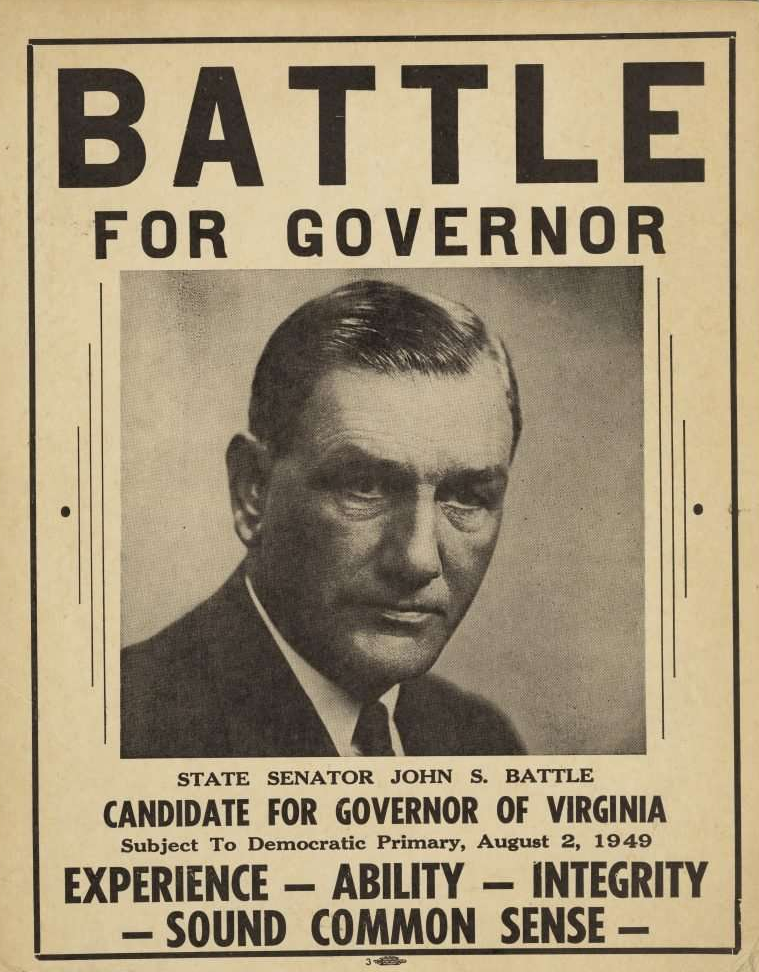

The last sitting member of the Virginia House of Delegates to be elected Governor was John Floyd of Blacksburg in 1849. The last sitting State Senator was John Battle, serving the Charlottesville area, in 1949.

No sitting US Senator has ever chosen to run for Governor of Virginia. The last sitting member of the US House of Representatives to be elected Governor was Claude Swanson in 1905, when he was serving the 5th District stretching from Pittsylvania County to Grayson County. Later, Thomas Stanley in 1953 and Colgate Darden in 1941 resigned their seats in Congress when they chose to run successfully to become the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia.22

the last sitting member of the General Assembly to win election as Governor was State Senator John Battle, elected in 1949

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, John Stewart Battle (1890–1972))

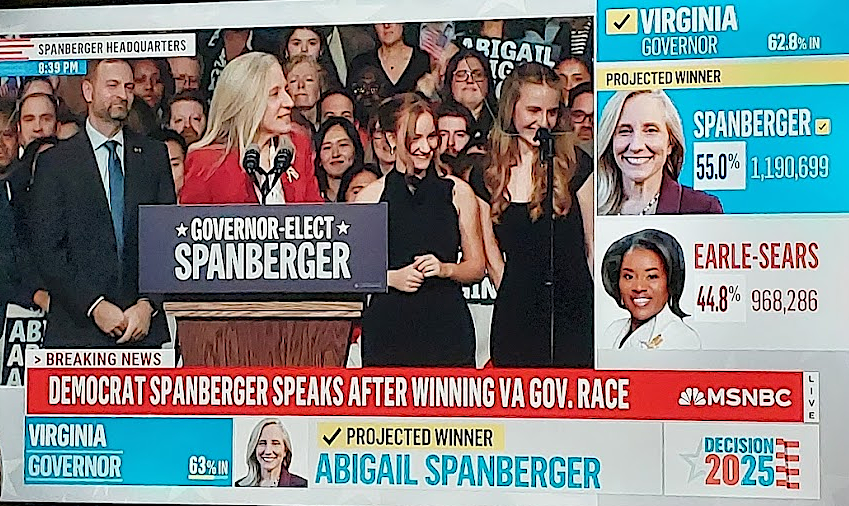

In 2023, immediately after the elections for seats in the General Assembly, Rep. Abigail Spanberger announced her decision not to run for re-election to the US House of Representatives from the 7th District. Instead, she chose to run for the Democratic nomination for Governor in 2025.

She won the Democratic Party nomination and the Republican Party nominated Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears. That guaranteed that Virginia would elect its first female governor on November 4, 2025. Prior to that election, Virginia had 74 male governors. OF that total, 43 were elected starting with Joseph Johnson in 1851. The remainder had been chosen by the General Assembly between 1776-1851.

Abigail Spanberger won the 2025 race. She gathered 57% of the vote in a Democratic sweep that increased her party's control of the House of Delegates from a narrow 51-49 margin to a commanding 64-36 majority.

The 43% of the vote for Winsome Earl-Sears was a historic low for any Republican candidate since Virginia became a two-party state in 1969. As noted by Dwayne Yancy at Cardinal News:23

Rep. Abigail Spanberger chose to run for Governor in 2025 rather than for re-election in 2024 to the US House of Representatives

Source: Spanberger for Governor)

It is irrelevant if a candidate for governor wins a majority of the 95 individual counties or 38 separate cities in Virginia. What matters is the total votes, statewide, for each candidate. There is no equivalent geographic impact in statewide races to the Electoral College used to count votes by state in presidential races. There is no advantage for a candidate for governor to win a particular town, city, or county; what matters is the number of total votes.

Candidates for governor campaign across the state, but all jurisdictions are not equally valuable to candidates. Some have far more voters that others. Candidates spend most of their time and their advertising money in the metropolitan areas of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads with a high number of voters.

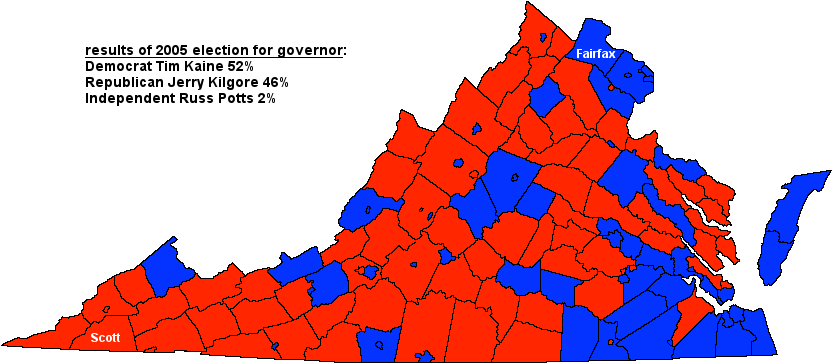

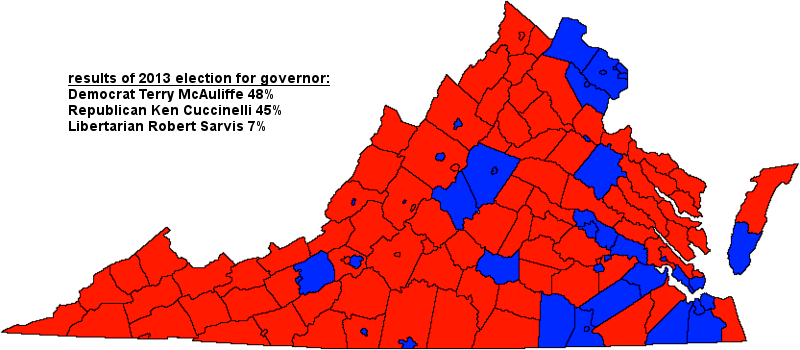

For the first decades of the 21st Century, the Republican candidates won the rural jurisdictions with low numbers of voters, Democratic candidates won the urban centers with a high number of voters, and the suburbs determined who won a statewide election.

Post-election maps that show a majority of the state colored red, indicating Republican majorities in most jurisdictions, are misleading. Population density is different in urban Democratic areas vs. rural Republican areas. The total number of votes in the blue-colored cities and densely populated counties for Democratic candidates may exceed the number of total Republican votes, even though the area colored blue is relatively small. In statewide races, Democratic officials have been elected by a majority of voters concentrated in a minority of local jurisdictions.

Votes count, not acres. Republicans who win the majority of low-population jurisdictions in Virginia will not celebrate victory on election night for governor, if the Democratic opponent wins more votes overall. When Republican Glenn Youngkin won in 2021, Democrats learned that they will not celebrate if rural turnout is high enough to outweigh the urban/suburban voters who traditionally support the Democratic candidate.24

in 1989, Southwestern Virginia was still a Democratic stronghold when Douglas Wilder won in Virginia's closest gubernatorial election in the Twentieth Century (blue indicates jurisdiction won by Democrat, red indicates jurisdiction won by Republican)

Source: Wikipedia, Virginia gubernatorial election, 1989)

in the 2005 governor's race, Republican candidate Jerry Kilgore won a 73% margin in his home territory of Scott County while the Democratic victor Tim Kaine won by only 60% in Fairfax County - but Kaine gained 163,644 votes in Fairfax County and Kilgore earned only 6,016 votes in Scott County

Source: Wikipedia, Virginia gubernatorial election, 2005)

in the 2013 governor's race, the successful Democratic candidate won only one county (Montgomery) west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Wikipedia, Virginia gubernatorial election, 2013)

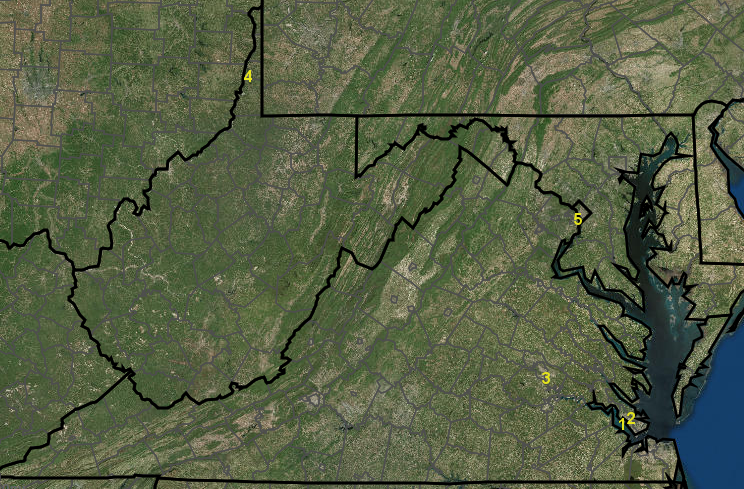

governors have ruled Virginia from five separate capitals at 1) Jamestown, 2) Williamsburg, 3) Richmond, 4) Wheeling, and 5) Alexandria

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online