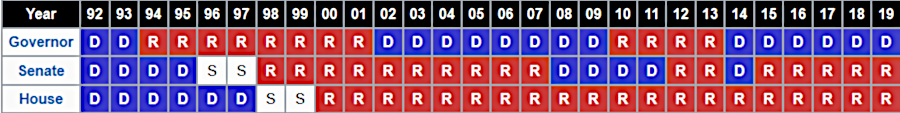

shared control of the State Senate occurred only in 1996-1997, because the Lieutenant Governor participated in procedural votes the other two times the State Senate was evenly split

Source: Ballotpedia, Party control of Virginia state government

shared control of the State Senate occurred only in 1996-1997, because the Lieutenant Governor participated in procedural votes the other two times the State Senate was evenly split

Source: Ballotpedia, Party control of Virginia state government

In the state legislature, both the House of Delegates (with 100 members) and the State Senate (with 40 members) could have tie votes. In tie vote in the House of Delegates equals a rejection of the proposal; the bill fails to advance for further action.

In the State Senate, the same rule applies for votes in subcommittees and committees. However, if a vote in the entire State Senate ends in a tie, the presiding officer (the Lieutenant Governor) is authorized to vote, creating a one-vote 21-20 majority. Partisan discipline usually ensures that one political party or the other controls each vote, so tie votes are most likely only when Republicans and Democrats each elect 20 people to the State Senate.

That has happened three times. There were 20 members of each party elected to the State Senate after the 1995, 2011, and 2013 elections.

After the 1995 election created a 20-20 split, the Democrats got advice from University of Virginia law professor A. E. Dick Howard, who had played a major role in crafting the 1971 state constitution. Democrats also consulted with Lane Kneedler, a former chief deputy in the office of the Attorney General. They advised that the constitution gave the Lieutenant Governor broad authority to vote as a member of the State Senate. They concluded that the Lieutenant Governor was a full member of both the legislative and executive branches of government.

From the perspective of the lawyers consulted by the Democrats, the state constitution was not intended to create a situation where the General Assembly would be paralyzed and unable to act on legislation due to a tie vote. In their interpretation, the Lieutenant Governor could use his tie-breaking vote on procedural matters, including the organization of State Senate committees, as well as vote on the budget.

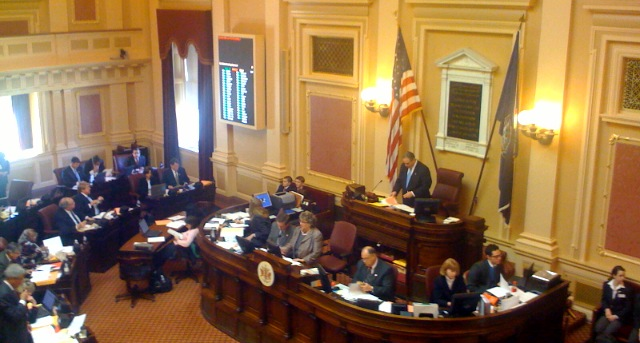

In 1995, the Lieutenant Governor was a Democrat, Don Beyer. He would not advance the governor's agenda because Governor George Allen, also elected in 1993, was a Republican. In the 20-20 split after the 1995 election, that vote would allow the Democrats to establish who would chair the 11 committees, thus enabling the Democrats to control decisions made in the State Senate.

Lieutenant Governor Beyer was blunt in his claim:1

the primary responsibility of the Lieutenant Governor is to preside over the State Senate

Source: Flikr, Senate Session (by Waldo Jaquith, January 21, 2008)

Allowing the Lieutenant Governor to cast a tie-breaking vote on procedural matters in 1995 might help Democrats initially, but result in a change of the State Senate in two years. A new election for Lieutenant Governor was scheduled for 1997. If a Republican was elected in 1997 and the Lieutenant Governor could vote on procedural matters, then the Republicans could take charge and chair all 11 committees until a new State Senate election on 1999.

Despite A. E. Dick Howard's opinion, the Attorney General (a Republican) claimed the Lieutenant Governor's authority to vote was limited. The state constitution said that only elected members of the legislature could vote on the budget and to choose judges. Governor Allen, also a Republican, said a tie-breaking vote on electing judges would not be acceptable; he would not acknowledge the legitimacy of new judges who might be chosen by such a process.

The role of the Lieutenant Governor is defined with minimal language in that part of the state constitution dealing with the Executive Branch:2

Other key language is in the separate section defining the role and responsibilities of the legislature (emphasis added):3

Left unclear in the constitution is whether the Lieutenant Governor is elected to the State Senate and is a full member with authority to vote on all issues, or allowed to vote only to break ties on bills that did not involve creation of new offices (such as judges), debt (statewide bond issues), appropriations (budgets), and taxes.

The Virginia Attorney General issued two opinions in 1980. They stated that the Lieutenant Governor was not a member of the Senate, but the Senate could allow the Lieutenant Governor to vote in order to break a tie on all issues other than those where Article IV of the state constitution explicitly prohibits such a vote. In 1996, the Attorney General issued an opinion that the Lieutenant Governor should not have been allowed to vote in order to break a tie on a proposed amendment to the state constitution.4

The stalemate after the 1995 election was broken not by a legal opinion, but by political pressure from conservative Democrats in the State Senate. State Senator Chuck Colgan and Virgil Goode forced their party to compromise. Goode even threatened to switch parties and align with the Republicans unless the Democrats accepted a balanced power-sharing agreement. State Senator Sen. Jane H. Woods on the Republican side threatened to vote with the Democrats if needed, to establish a fair bargain on control of the 11 committees.

The two sides agreed to a deal that would last four years. They recognized that the Democratic Lieutenant Governor could be replaced by a Republican Lieutenant Governor in the 1997 election, and did not want to go through the headache of forging a new compromise if that occurred.

Democrats ended up as the chairs for six committees, and Republicans chaired four. Co-chairs were selected for the powerful Senate Finance Committee. There were 8 Democrats and 7 Republicans on all committees except the Senate Finance Committee, which was expanded to create a 9-8 Democratic majority.

Virgil Goode was given a coveted seat on the House-Senate conference committee which negotiates the final compromise for the biennial state budget, but he was clearly no longer welcome as a member of the Democratic team. Within a month, he announced he would run for a seat in the US House of Representative.

After the 1995 elections created a 20-20 tie, the compromise on organizing the State Senate offered a clear contrast with the pattern set four years earlier after the 1991 elections. At the start of the 1991 campaigns, the partisan ratio in the State Senate was 30-10. After the elections, in districts with new boundaries drawn after the 1990 Census, the ratio dropped to 22-18. Democrats retained full control, though by a much-diminished number of seats, and minimized the potential for Republicans to delay or block the majority party's agenda. In the organization of the State Senate in 1991, just three Republicans were allowed to serve on the 15-member Senate Finance Committee.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch described the 1995 compromise, which happened only due to the potential defections of Senators Goode and Colgan, "a bitter pill for the Democratic leadership." The newspaper also noted that if the state's constitution had clearer language, "constitutional scholars could spend more time at the beach."

On February 5, 1996, Lieutenant Governor Beyer cast his first vote. The State Senate had reached a 20-20 tie on a proposed amendment to the US Constitution. The split was not purely partisan, and the tie vote had already blocked the proposal from going forward, but the Lieutenant Governor took the first opportunity to vote. He voted "no," so his vote did not change the outcome, but it set a precedent on his right to participate in the chamber's decision process.

Governor George Allen and Attorney General Jim Gilmore, both Republicans, immediately accused Beyer of making a "power grab." They pushed an interpretation of the state constitution that would limit the authority of the Lieutenant Governor, because someone from the opposite political party sat in that chair in 1996.5

Another test of the position's authority came in 1997. The 20 Democrats proposed electing to the Virginia Supreme Court someone unacceptable to the 20 Republicans. That could have created a test case, but every court in the state which could rule on the issue was headed by a judge appointed by the General Assembly. Any Circult Court judge hearing the case would have to deal with both a separation of powers issue and a potential conflict of interest, since the General Assembly appoints those judges to six-year terms.

Though most incumbent judges are re-appointed, the elected politicians have the power to block another term if a judge has made an unpopular decision. The risk is not just theoretical. Circuit Court Judge Richard Pattisall failed to get reappointed in 2002. He had ruled in 2001 that the redistricting plan prepared by the Republican-controlled House of Delegates was unconstitutional.6

A case could have been filed in the court of a judge not seeking reappointment, but the 20 Republicans found another solution. They chose not to vote on the proposed appointment. Judicial appointments require, under the state constitution, an "affirmative vote of a majority of all the members elected to each house" - which is 21 votes in the 40-member State Senate. The 20 votes of the Democrats lacked a majority of the State Senate. With a 20-0 vote, there was no tie which would allow the Lieutenant Governor to vote.7

The power-sharing deal which was negotiated in 1995 was designed for four years, until the 1999 elections at the end of the four-year terms for State Senators elected in 1995. The power-sharing deal ended up lasting only two years.

Another Republican, Jim Gilmore, was elected Virginia's governor in 1997 to replace George Allen. In that race his opponent was the Lieutenant Governor, Don Beyer. John H. Hager was elected as the new Lieutenant Governor to replace Beyer.

Hager was a fellow Republican. He could have broken the 1995 power-sharing bargain and used his tie-breaking vote to reorganize the State Senate. The legitimacy of that approach might have been questioned, and the relationships among members of the State Senate would have been soured even further by a clear "power grab" replacing the power-sharing agreement.

Governor Gilmore had been Attorney General in 1996 and issued the opinion that Democratic Lieutenant Governor Beyer could not vote on amendments to the Federal constitution. It would have been logically inconsistent for him to flip his opinion and assert two years later that Republican Lieutenant Governor Hager had more authority than his predecessor.

Governor Gilmore found an alternative way for Republicans to establish a majority in the 20-20 State Senate, without claiming the now-Republican Lieutenant Governor had broad authority to vote.

After the 1997 elections, Governor Gilmore quickly and skillfully reshaped the partisan split in the State Senate by a different approach. He offered jobs to Democratic incumbents.

One Democratic State Senator accepted an offer to become deputy transportation secretary. When State Senator Charles L. Waddell accepted the executive branch position offered by the governor, he left the State Senate halfway through his term.

By facilitating the shift to Republican control in the General Assembly, State Senator Waddell sacrificed any future political ambitions. However, the full-time job provided a much higher salary compared to the part-time compensation for a State Senator. The higher salary for the last three years of his government service dramatically increased the retirement pay of the former legislator, increasing financial security for the rest of his life.

A special election for Waddell's vacated State Senate seat was held in January, 1998. As Governor Gilmore anticipated, a Republican was elected with 61% of the vote to replace the Democrat. The partisan split in the State Senate changed from 20-20 to 21-19, with Republicans in the majority.8

The State Senate was equally divided again after the 2011 election. After the 2010 Census, the General Assembly and the governor agreed on new boundaries for political districts. The Republican-controlled House of Delegates drew partisan boundaries benefitting that party, and the Democratic-controlled State Senate drew partisan boundaries benefitting that party.

Despite having the ability to draw new State Senate boundaries that benefitted their party, two Democratic incumbents in the State Senate were defeated in the Fall elections. That created another 20-20 split.9

Lieutenant Governor Bill Bolling was a Republican, as was Gov. Bob McDonnell. The Republican leadership revised its previous perspective on Professor A. E. Dick Howard's advice in 1995, and of Attorney General Gilmore's opinion in 1996. Lieutenant Governor Bolling voted on organizing the committees that made most decisions in the State Senate.

The Democrats called his actions a "power grab." There was no power-sharing agreement comparable to the one negotiated after the 1995 elections. Only Republicans were appointed as committee chairs, and there were no co-chairs. Republicans were appointed to a majority of seats on every committee except Local Government and Rehabilitation and Social Services.

After Bill Bolling was elected Lieutenant Governor in 2011, the Democratic leadership adopted a partisan perspective quite different from 1995. After Don Beyer had been elected in 1995, Democrats claimed broad powers for the Lieutenant Governor's ability to break a tie and act as the 21st member of the State Senate. In 2011, one Democrat articulated the new perspective of the party out of power:10

No one suggested the Lieutenant Governor could cast a tie-breaking vote on the budget. In 2012, the 20 Democrats and 20 Republicans could not agree on a budget. Deadlock was extended because no compromise was negotiated, and the state constitution required that Lieutenant Governor Bolling sit on the sidelines.

Resolution finally came after an extra month of debate, during which Democrats failed in their efforts to get the Republicans to compromise on power sharing in exchange for votes in support of the budget. State Senator Charles Colgan, a conservative Democrat, switched his vote and voted for the Republican budget. His Democratic colleagues were caught by surprise, but Colgan had crossed party lines before and was not planning to run for re-election.11

In the Fall 2013 elections, there were no State Senate races because those terms ran from 2011-2015. However, Democrats from the State Senate won the races for Lieutenant Governor and Attorney General. That dropped Democratic membership from the 20-20 tie to 20-18.

On January 7, 2014 a Democrat was elected to replace Ralph Northam because he had been elected as Lieutenant Governor. The State Senate race was so close that results were delayed by a recount. The second race to replace Mark Herring, elected as Attorney General, did not occur until January 21. Before leaving office at the end of his term, Republican Governor Bob McDonnell had scheduled that race very late. The delays in replacing the two state senators gave the Republicans a majority in the State Senate for the first three weeks of the legislative session.

After the recount concluded and a Democrat won the race to replace Mark Herring, the Democrats had 20 members in the State Senate again. They repeated the "rearticulation of Senate rules" used by the Republicans in 2012 after the 2011 election create a 20-20 tie. With the tie-breaking vote of Lieutenant Governor Northam, Democrats reorganized the State Senate. A majority of Democrats were appointed to all committees except Local Government and Rehabilitation and Social Services.

A Democrat replaced the Republican chair on 10 State Senate committees. The Democrats did allow a Republican to co-chair the Senate Finance Committee, but switched membership to create a 11-6 Democratic majority to replace the 10-5 Republican majority. When Republicans complained about the reorganization in the middle of the four-year terms, the Democratic Majority Leader said:12

The Democratic governor's #1 priority was Medicaid expansion so 400,000 low-income Virginians could get more access to low-cost health care as authorized under the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"). The governor's policy decision was proposed in the budget, but the 20 Republican State Senators refused to approve it.

The 20-20 deadlock could not be broken by the Lieutenant Governor; by 2014, it was well accepted that a Lieutenant Governor was not authorized to cast a tie-breaking vote on an appropriations bill. The budget debate continued into June, 2014, long past the normal date for approving a budget at the end of the regular session in March/April.

The stalemate made it impossible for school systems and county/city governments to estimate state aid and complete their local budgets. Delay also threatened to leave state agencies without authority to spend money after the next fiscal year started on July 1. A "shut down" of state government operations was possible.

An unexpected resolution came with the resignation of Phillip Puckett, a Democratic State Senator, in June 2014.

State Senator Puckett wanted his daughter to be elected as a Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court judge. The House of Delegates, already controlled by Republicans, had voted for her twice The State Senate traditionally refused to elect as judges any children or spouses of members sitting in the State Senate. Democrats accused Puckett of bargaining with the Republicans to resign his seat, then have his daughter elected by the General Assembly once the Republicans controlled the Senate by a 20-19 majority.

Rumors also circulated that Puckett would also get a new job for himself, as deputy director of the Virginia Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission. That agency was chaired by a Republican member of the House of Delegates.

As part of the surprise resignation, State Senator Puckett and his wife cleaned out his office on a Sunday. There was no advance notice for movers to help pack and transport his personal items, so the two of them collected trash cans in the building and used them as packing boxes.13

The next day, with a 20-19 majority, Senate Republicans used their new majority to make Republicans the committee chairs in the State Senate. Governor Terry McAuliffe had to negotiate a new budget for 2015-17 without Medicaid expansion. He left former State Senator Puckett a bitter message on his voicemail:14

Puckett was never offered any job with the Virginia Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission. Gov. Bob McDonnell had been charged recently by federal prosecutors with corruption, and there was high sensitivity to the perception of another state scandal.

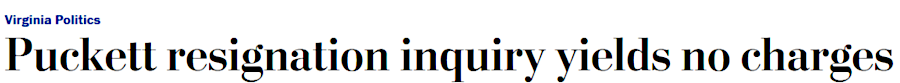

Puckett may have once been offered a position with the state agency by Republican leaders, but Democratic leaders (including Gov. McAuliffe's chief of staff) may have offered him jobs as well. After resigning, he ended up returning to his regular job in the private sector at a Southwest Virginia bank. A Federal investigation of various job offers was closed without any charges being filed.15

the perception that State Senator Puckett was offered a job inappropriately to spur his resignation led to an investigation by federal prosecutors

Source: The Washington Post (December 12, 2014)

The vacant seat in Puckett's 38th District was filled by a Republican, giving that party a clear 21-19 majority. Despite strong efforts by the Democratic Party to gain at least one seat in the 2015 election cycle and allow the Lieutenant Governor to break ties again, the partisan split in the State Senate remained 21-19 for another four years. Governor McAuliffe was never able to get Medicaid expanded during his term.

Republicans still controlled the State Senate by that 21-19 majority in 2018 when Medicaid expansion finally occurred. The shift in policy came in response to a "blue wave" in the 2017 election, which replaced 15 Republicans in the House of Delegates with 15 Democrats. The 66-34 split in the House shifted to a 51-49 split. The Republican majority in the House was continued for two more years only after a Republican candidate was selected by chance to win an unusual race that had ended with a tie vote.

After the 2017 election, Republicans in the State Senate recognized the political necessity to approve Medicaid expansion. That approval in 2018 removed the issue from discussion before the 2019 elections, reducing the potential for another "blue wave" that might sweep more Democrats into the State Senate.16

In 2019, the General Assembly chose to elect the sister of a sitting State Senator to serve a 12-year term on the Virginia Supreme Court. In 2019, the Republicans still controlled the State Senate by their 21-19 majority, thanks to the resignation of Democratic Senator Phillip Puckett in 2014 and the election of a Republican to fill that seat in 2014 and in the regular 2015 election.

Senator Ben Chafin, brother of the candidate for a seat on the Virginia Supreme Court, even chose to stay in the Courts of Justice Committee hearing when his sister and three other candidates were interviewed. He did not ask questions, and when it came time to vote on the floor of the Senate he did not participate in that decision.

The sister of State Senator Ben Chafin joked in her interview that she had been elected as a lower court judge 11 years before her brother was elected to the General Assembly, so if there was nepotism in the process of choosing government officials then he was the beneficiary. Others noted that Ben Chafin had been elected to the State Senate to fill the vacancy caused when Senator Phillip Puckett resigned in 2014, because he had hoped that leaving the State Senate would eliminate nepotism concerns and enable his daughter to be chosen as a judge.17

headline showing the anti-nepotism policy regarding election of judges related to sitting members of the State Senate changed in 2019

Source: The Roanoke Times (February 6, 2019)

In the 2015-2019 General Assemblies, Republicans had control of the State Senate with a 21-19 majority. There was proportional representation, with Democrats given just slightly fewer members than Republicans, on all but the two most important committees. On the Senate Finance Committee, there were 11 Republicans and only 5 Democrats. On the Commerce and Labor Committee, there were 11 Republicans and 4 Democrats.

The 2019 election flipped control of the State Senate to the Democrats, and they held a 21-19 majority when the General Assembly opened in January, 2020. Republicans complained that in the new legislative session, on the Senate Finance Committee there were 10 Democrats and 6 Republicans. On the Commerce and Labor Committee, the new ratio was 12-3.

The State Senate was not split 20-20, and the balance of power was reflected in the appointments. The Democratic Majority Leader create 8-7 Democratic majorities on half of the 10 committees in the State Senate. Regarding the unbalanced ratio on two most powerful committees, he commented about Republican calls for proportional representation:18

Having 20 Republicans and 20 Democrats in the State Senate is not required to create an opportunity for the Lieutenant Governor to cast a tie-breaking vote. In 2021, for example, Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax broke a 19-19 vote to support a bill moving all local elections to November. Two of the 21 Democrats in the State Senate opposed the bill, and one Democrat did not vote. One Republican joined the remaining 18 who supported it, and one seat was vacant after a State Senator died just before the session started.19

In 2023, Democrats had a 22-18 majority. Two of the 22 Democrats in the State Senate joined with all 18 Republicans to support one of Governor Glenn Youngkin's nominees to the Board of Visitors at the University of Virginia. That 20-20 vote enabled Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears to cast her vote in favor of the controversial nominee, who had been opposed by students and faculty at the university.20

Two years later, as Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears prepared to run as the Republican nominee for Governor, Democrats in the State Senate engineered a tie vote to force her to make a public decision on a controversial issue. On January 28, 2025, there were 21 Democrats and 18 Republicans on the floor when it was time to vote on a bill that would guarantee the right to obtain contraceptives.

It would have been a 21-18 party-line vote for approval, but one Democrat abstained and one voted against the bill in order to manufacture a 19-19 tie. That forced the Lieutenant Governor to cast a ballot, and as expected she voted against the right to contraception bill. The Democrats gained the opportunity to highlight her "anti" vote in the upcoming gubernatorial campaign, and then brought the bill back for another vote in which it passed.21