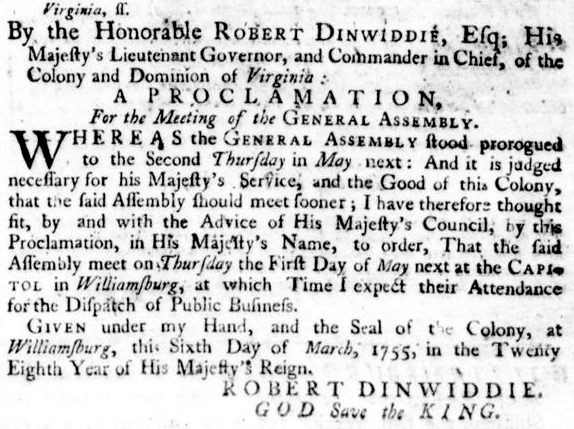

at the start of the French and Indian War, Gov. Dinwiddie called the General Assembly into session

Source: Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia Gazette (Hunter: March 21, 1755, p.4)

at the start of the French and Indian War, Gov. Dinwiddie called the General Assembly into session

Source: Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia Gazette (Hunter: March 21, 1755, p.4)

When the General Assembly started in 1619, the Virginia Company began to grant authority to the residents in the colony to govern themselves. Since the arrival of Sir George Yeardley from Bermuda in 1610, the company's appointed governor had possessed all executive authority in Virginia. The Virginia Company chose to share authority with colonists, and reduce the power of the governor, by issuing the Great Charter in 1618.

That set of instructions in 1618 created the headright system, offering 50 acres of land to all new settlers. Creation of a colonist-led General Assembly and an appointed Council of State to advise the governor was expected to alter the negative perception that colonists must accept arbitrary Virginia Company policies in Virginia.1

When the private company lost its charter and Virginia became royal colony in 1624, the king or queen of England appointed a Royal Governor and a Council of State to advise him. Officials in London issued royal instructions to the governor, who sought to shape the decisions of the elected House of Burgesses and the appointed Council of State (Governor's Council). The governor decided when the House of Burgesses would start meeting, when it ended, and when there would be elections for new burgesses.

The colonial governor in Jamestown and then Williamsburg had substantial leverage, including the ability to determine who received appointments to various official positions that generated fees for the appointee. The governor had to sign bills passed by the House of Burgesses. However, exercising his right of disallowance by refusing to sign a bill would lead to a fight with the wealthy Virginia elite with whom the governor socialized.

To block passage on an undesired bill, it was easier for the governor to mandate an immediate cessation of a meeting of the House of Burgesses. He could issue an order to "prorogue" the legislature, forcing an end to a meeting but leaving the membership of legislature unchanged until he recalled the House of Burgesses back into session later. The governor also had the option of dissolving (rather than just proroguing) the House of Burgesses, forcing a new election in which some members might retire or might not get re-elected.

During the colonial period, the Governor's Council could refuse to assent to a bill and block action by the House of Burgesses, but the Council also could outvote the governor and approve a law despite his opposition. When outvoted by his Council, the governor had one more option. Laws passed by the General Assembly required royal assent before going into effect. The royal governor could advise the Privy Council in London to exercise the king's prerogative to veto legislation.

Governor Harvey established the principle that royal assent, as required for laws of Parliament, would also apply to laws passed by the provincial assembly in Virginia. In 1631 the General Assembly sent all of its laws to London for approval. The burgesses asked that the review accept that the form of the laws might be technically imperfect, since few colonists had training in the law.

The first disapproval of a Virginia law occurred after the General Assembly passed a series of laws in 1677 during Bacon's Rebellion. All legislation from that session was vetoed by the Privy Council in 1678.

The Privy Council create a committee to review laws submitted by all the colonies. Starting in 1718, a special solicitor managed the review process and submitted reports to the committee with comments from the Board of Trade, other British officials with an interest, and affected merchants. A response to a colony typically required up to three years. The perspective in London was that new colonial laws were subject to a "suspending clause;" they could not go into effect until approved by the Privy Council.

The power of the king and queen in England to veto laws faded over time, as the role of Parliament grew. The last veto of a bill passed by Parliament was in 1708. However, Parliament did not view the provincial assemblies in the colonies as equivalent elected representatives of the people and did not empower those legislatures to block royal guidance. Instead, Parliament supported the veto power of the king's appointed governors in order to retain London's authority over colonial legislatures.

As seen from London, colonial governors and assemblies both were exercising powers granted to them by royal choice. The ability of colonial assemblies to make decisions was limited to the extent the king or queen had chosen to provide. As seen in Parliament, it had an inherent right to make laws for all British subjects but the legislators elected in the colonies had none. The colonies had only the authority defined by the king, as interpreted by the Privy Council.

Bills that limited royal powers, expressed in instructions to appointed governors, were subject to Privy Council vetoes if the colonial governors had not chosen to block the bills. One veto blocked a bill passed by the General Assembly to alter the charter of Norfolk, because the Privy Council wanted to assert that only the king could grant charters.

Colonies could not constrain or revise laws which had been passed by Parliament, such as the Navigation Acts or trade with Native Americans. Bills that impacted relations between the colonies drew special scrutiny. When the North Carolina legislature passed a law to encourage Virginia traders with the Native American tribes to move into North Carolina and to tax such traders, London officials cancelled the bill to protect the Virginians. When Virginia tried to impose a tax on cargo entering the Chesapeake Bay in order to fund a lighthouse at Cape Henry, the bill was killed in London to protect the Maryland colonists.

English merchants ensured the Privy Council blocked bills affecting rates of exchange or bankruptcy that would impact profits. Attempts to create local taxes on ships or goods imported into the colonies were routinely vetoed. A bill to create a local "court of hustings" in Williamsburg was annulled because merchants anticipated colonial judges and juries in Virginia would not be sensitive to the concerns of merchants in England.

Sometimes bills passed by the General Assembly that affected influential Virginians were also annulled. William Byrd II claimed credit for getting two bills vetoed while he was living in England, the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1713 and the Indian Trade Act of 1714. Byrd was feuding with the lieutenant governor, Alexander Spotswood, and lobbying in London to get him recalled. That effort did not succeed while Byrd was in England, but he did interfere with Spotswood's efforts to set public policy.

At times, the London officials would return a bill to a colonial legislature with amendments. If not adopted, only then would the original legislation be blocked. The process was roughly comparable to the way Virginia governor's now recommend amendments to the General Assembly.

The practical authority of the colonial governor morphed over time, reflecting the increasing economic power of the First Families of Virginia who controlled tobacco exports. Even in the early days of the colony, there were conflicts between the legislature and the appointed governor. The General Assembly "thrust out" Governor Harvey out in the 1630's, declaring he was no longer the governor and forcing him to get on a ship sailing back to England. That was a direct challenge of the power of King Charles I to appoint the governor of his colony, which had become a royal colony when the Virginia Company charter was dissolved in 1624.

The king responded by sending Governor Harvey back to Virginia for just a token term of service. His replacement, Sir Francis Wyatt, re-established the authority of the royal governor.

The next governor, Sir William Berkeley, then negotiated deals with the gentry that dominated the House of Burgesses. Over time, his dominant personality minimized the checks and balances within colonial government. Governor Berkeley appointed legislators and their family members to positions that required high taxes and fees to pay the salaries, and in return the colonial officials endorsed the governor's policies. That process enriched just a few officials rather than provided services for the majority of colonists. High taxes, and inequality of the opportunity to gain wealth and influence beyond a narrow group of families, helped trigger Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.

Starting with the appointment of Sir Thomas Culpeper in 1677, royal governors chose to stay in England. Governors were men who had influence with the king, and sailing across the Atlantic Ocean to live in isolated Jamestown far from the court circles in London was not an attractive option. Governor Culpeper sent a lieutenant governor to Virginia to actually serve in the role. Until 1768 the official governor selected his lieutenant who served in Virginia and represented the king/queen in the colony, and paid him a portion of the governor's royal salary.

During the 1700's, the House of Burgesses control over taxes and appropriations allowed the Virginia gentry to gain power over the lieutenant governors. In 1768, as London officials sought to centralize control over all the colonies and generate revenue for new taxes, George III required Lord Botetourt to go in person to Virginia and enhance the power of the appointed executive official over the elected legislative.

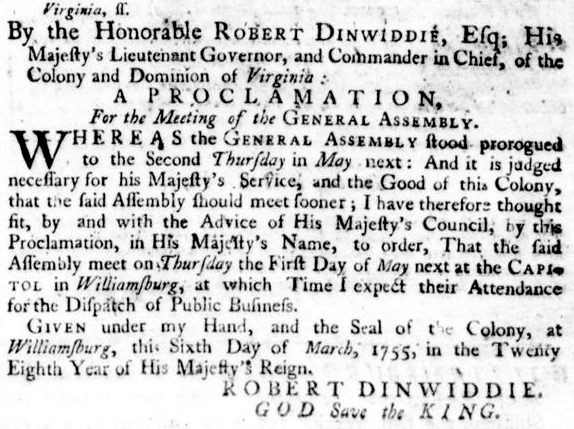

In the 1760's and early 1770's, proroguing/dissolving the House of Burgesses and the use of the royal prerogative to block colonial laws spurred Virginians to rebel against the authority of British officials. The decision of the Privy Council in 1759 to void the Two Penny Act, which limited compensation of Anglican ministers, led to the rise of Patrick Henry. The veto did not declare that the Anglican ministers were entitled to back pay, so they filed suit in Hanover County. Henry's eloquent complaints about royal power while pleading the Parson's Cause lawsuit in 1763 stirred the emotions and the thinking of colonial leaders, prior to their coordinated response to oppose the 1765 Stamp Act.

Objections to Privy Council vetoes widened to colonial claims that the elected Parliament and the king lacked the power to establish laws in Virginia. The Fifth Virginia Convention finally declared Virginia to be an independent state in June, 1776, eliminating all power based in London. Privy Council decisions to veto bills that would limit importing slaves (thus increasing the value of enslaved workers already in Virginia) was one issue which Thomas Jefferson cited a short time later in 1776, when he compiled grievances for the Declaration of Independence.

The members of the Fifth Virginia Convention were opposed to creating another strong executive in the new state government to replace the role of the British king. The first state constitution, adopted in 1776, reduced the governor's authority by having the legislature appoint him to a fixed one-year term, with a maximum of two subsequent terms.

Patrick Henry was elected the first governor by the General Assembly; not until 1851 was the governor elected directly by the people of Virginia. Henry's many opponents supported his election because moving him to the governor's office reduced his capacity to shape legislation through his extraordinary speaking ability in the General Assembly. As governor, he lost the ability to speak during legislative meetings or to vote on bills.

Under the first state constitution adopted in 1776, the legislature was perceived as the primary agent of the people. In contrast, during the colonial period the royal governor was the agent of the king or queen, not the residents of the colony. Virginia's first constitution did not give the governor authority to veto specific bills except with the approval of the Council of State - which was appointed by the members of the General Assembly to ensure the governor complied with legislative priorities.

By 1787, only Massachusetts and New York had constitutions which clearly granted their governor the right to veto bills passed by the state legislature. The US Constitution gave only qualified veto power to the President, and the US Congress was allowed to override a veto. George Washington vetoed only two bills, but he set the precedent. Until the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828, the first six US presidents vetoed only 10 bills in total. Not until 1845 did the US Congress override a presidential veto, on the 34th time one had been issued.

As the first governor of Virginia, Patrick Henry also could not block meetings of the legislature like colonial governors. The 1776 state constitution declared:2

Patrick Henry was elected the first governor after Virginia declared its independence in 1776, and placing him in that executive position minimized his power in the state government

Source: Library of Congress, "Give me liberty, or give me death!" Patrick Henry delivering his great speech on the rights of the colonies, before the Virginia Assembly, convened at Richmond, March 23rd 1775, concluding with the above sentiment, which became the war cry of the revolution

The ability of a governor to exercise executive authority has grown gradually but substantially since 1776. In 1830, a new state constitution created a three-year term for the governor, though sequential elections were banned to ensure no executive gained too much political power. The 1851 constitution extended the governor's term to four years, while also starting the process of electing governors directly by the voters rather than by the legislature.

In 1870, a new state constitution gave the governor the power to veto bills passed by the General Assembly. If he rejected a bill passed by the two houses of the legislature, they could override his veto by re-passing the bill with a two-thirds majority of all the members present. However, the governor gained the power to block legislation that may have been endorsed by a majority of legislators, but was opposed by at least one-third of the members in each house.

The governor was also given the opportunity in the 1870 constitution to allow a bill to become law without his approval. If he simply failed to act on a bill within five days after it was sent to him, it became law automatically. However, if the General Assembly adjourned within that five-day window, any bill not signed by the governor was "pocket vetoed." As a result, the governor had greater authority over legislation passed at the very end of a legislative session.3

Since the 1902 constitution was proclaimed to be in effect, Virginia governors have had the right to propose amendments to legislation. The General Assembly had to approve the amendments for them to go into effect. If the amendments came too late in the session for consideration or were rejected by the legislature, then the recommended changes would not be incorporated into the bill. That left the governor with the option of accepting the original legislation as passed by the General Assembly, or vetoing it.

The 1902 constitution also expanded the power of the governor by authorizing the line item veto for appropriations bills. Since 1902, a governor has been able to veto just a slice of the state budget, the line that allocates money to a state program. The budget line item veto authority had first been included in the constitution adopted by the Confederate States of America.4

Between 1870-1928, the governor's veto power was one of his few management tools for controlling state operations.

In 1928, Governor Harry Byrd led a reorganization of state government that culminated in major amendments to the state constitution. In that process, the governor's authority to manage the executive branch was greatly expanded. He gained control over previously-fragmented state agencies. Centralized decisionmaking and financial management since 1928 has enabled the governor to shape the implementation of laws without having to veto them.

Based on the 1971 constitution, the governor can sign, veto, or propose amendments to bills passed by the General Assembly. The "pocket veto," blocking a bill from becoming a law by taking no action, is no longer an option in Virginia. If the governor refuses to sign or veto a bill, then the state constitution says that it automatically becomes a law.5

The governor has seven days to act, if the General Assembly is still in session after it has delivered a bill to the governor's office. If the bill was passed at the end of the session and the General Assembly adjourned within seven days of delivery, or if the bill was delivered after the session had ended, then the governor has 30 days to act on it.6

since 1849, the governor has had an office on the third floor of the state Capitol

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Virginia State Capitol - Third Floor Virtual Tour

The percentage of bills approved by both houses but ultimately blocked by the governor normally is tiny, unless the governor belongs to one political party and both houses of the legislature are controlled by the other party. Threats of a veto normally are sufficient to force compromises before both houses invest the committee and floor time required to pass a bill.

In the General Assembly's January-March 2019 session, by one calculation the governor signed 883 laws passed by both houses, vetoed 17 bills, and recommended amendments to 48 others. He also suggested 40 amendments to the appropriations bill, giving legislators a chance to modify the budget before exercising his line item veto authority.7

Under the state constitution, the General Assembly can override any veto by a vote of two-thirds of the members present in the House of Delegates and two-thirds of the members present in the State Senate. However, between 1902-1980 governors could veto bills passed at the end of the session with confidence that the veto would stick. The General Assembly would not reconvene for another year and have a chance to override the veto, unless two-thirds of the members in each house called for a special session.

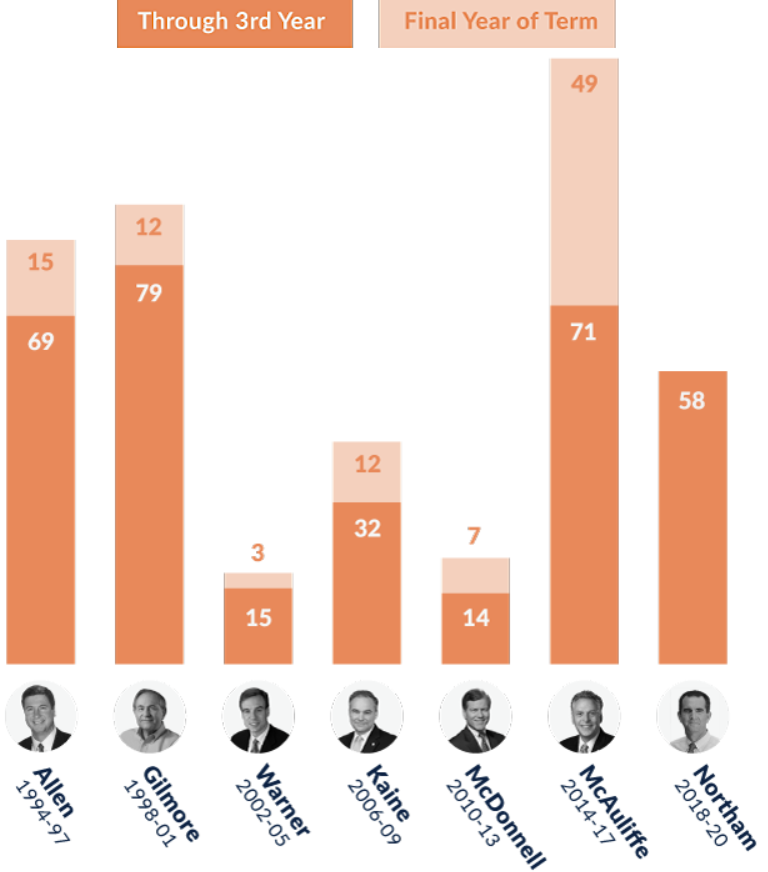

Constitutional amendments passed in 1980 and 1994 have created today's automatic Reconvened Session (often called the "veto session") of the legislature. Reconvening the General Assembly on the sixth Wednesday after adjournment gives it an opportunity to override the governor's vetoes of legislation passed in the last session, and to approve, modify, or reject amendments proposed by the governor. There are typically more amendments by the governor to address than vetoes in the reconvene session.8

The governor's amendments can be rejected by the General Assembly. If it does not concur, the legislation with rejected amendments is returned to the governor for action. If the governor vetoes the bill, then it does not become law. If the governor takes no action on the bills with rejected amendments, then the original legislation becomes law after 30 days.

The alternatives are:9

If a governor's proposed amendment is approved by a majority in each house during the veto session, the governor's revision becomes part of the new law. An amendment proposed by the governor can be altered by the General Assembly; it is not a "take it or leave it" proposition.

Determining how an amendment might alter all aspects of existing or proposed law is not always clear and simple. A governor could even submit contradictory amendments for consideration. An amendment may trigger negotiations that result in a substantive change in the bill, which can become law if the modified version is approved by both houses and signed by the governor.

In 2019, for example, the General Assembly could not resolve how to pay for upgrades to I-81. It passed a bill creating the I-81 Corridor Improvement Fund but rejected proposals to generate funding, after the trucking industry objected to plans for adding tolls to the interstate highway. Via an amendment, Governor Northam proposed a different funding mechanism, based on a regional tax on gasoline sales and a statewide increase in truck registration and diesel fuel taxes. That was acceptable to the legislators in the region, and the amendment led to a final decision rather than an extension of debate for yet another year.10

If both houses do not approve an amendment as proposed or in some revised version, the governor has two choices. The governor can agree to let the original bill become law, without the amendment, or can veto the law.

the General Assembly has an automatically-scheduled "veto session"

Source: Virginia Legislative Information System, Constitution of Virginia

A governor still has one path for preventing the General Assembly from overriding his or her veto. After the veto session adjourns, the governor can veto an amended bill. Typically that occurs when the amendments were altered, but a veto is possible even if the governor's proposed amendments had been accepted without change. Unless the General Assembly meets in a special session later that year, there is no opportunity to override a veto which occurs after the veto session until the next regular session. At that point, almost a year later, legislators can pass new law to "correct" the veto, but an election before the next regular session might have altered the membership of the General Assembly.

The governor's "line item veto" authority for appropriations bills can modify a budget without vetoing the entire bill. A veto of the entire budget would be a drastic action. It could leave the state unable to legally incur any expenses, dramatically interrupting operations.

A governor who exercised the "nuclear option" and vetoed a budget would increase costs for the state to borrow money for many years in the future, if bond rating agencies concluded there was a higher risk that Virginia officials might not pay bills for contracts or get to closure on planned economic development deals. Vetoing a line item enables a governor to eliminate funding that would implement a policy initiative which the governor opposed, but could not block by vetoing a different bill - and without vetoing the entire budget.

The governor does not have the authority to increase or reduce the appropriated amount, or to retain the funding but redirect its use.

The entire line in the appropriation bill must be vetoed, ending all funding for that item and eliminating the direction on how it should be spent. Each line item must have a distinct purpose, so the impacts of an appropriation and a veto would be clear to the voters.

Appropriations item in budget bills passed by the General Assembly must have comply with the "single object" requirement in the state constitution. That requirement blocks legislators from combining unrelated issues into one line item, "logrolling" separate parts together. The logrolling practice could capture support from different members of the General Assembly who might vote for the consolidated language in order to get the one piece they desired, even though there was not a majority within the legislature for any of the pieces individually.

The Supreme Court of Virginia used to be the ultimate umpire who could determined if a bill meets the single object standard. For budget bills, it has stated:11

The legislature has clawed back some of its power regarding how it considers gubernatorial amendments. In 1994, voters approved a revision to the state constitution which gave the legislature authority to determine, by majority vote of the members present in either house, if one or more amendments proposed by the governor were specific enough for a separate vote. If not, then the amendments could be ignored. The unchanged bill, as originally passed, would be returned to the Governor for complete veto or complete approval.12

In 2011, the General Assembly overrode one bill that Governor Bob McDonnell had vetoed. He tried to limit the amount which could be awarded by courts in medical malpractice cases. The House of Delegates voted to override the veto by 93-7, and the State Senate vote was 29-11.13

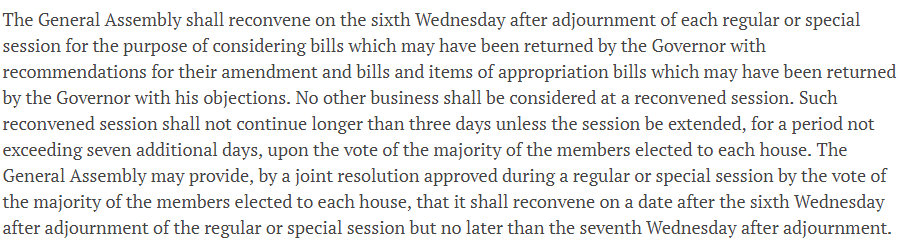

Governor Terry McAuliffe set a record for Virginia governors and vetoed 120 bills while serving in 2014-2018, including proposals to deny public funding to Planned Parenthood because it offered abortion-related services. None of his vetoes were overturned by the General Assembly, even though both houses were controlled by the opposition party (Republicans) during his term. Gov. McAuliffe made 80 amendments to appropriations bills during his four-year term, and the General Assembly approved over 80% of them.14

One of the hottest amendments not accepted from Gov. McAuliffe was his proposal to expand Medicaid and implement "Obamacare" in Virginia. That expansion did not occur until after the 2017 election, when a "blue wave" flipped 15 seats in the House of Delegates and the Republican majority dropped to 51-49. In the first year of Gov. Ralph Northam's term, the General Assembly approved Medicaid expansion as part of a regular bill, not through the amendment process.

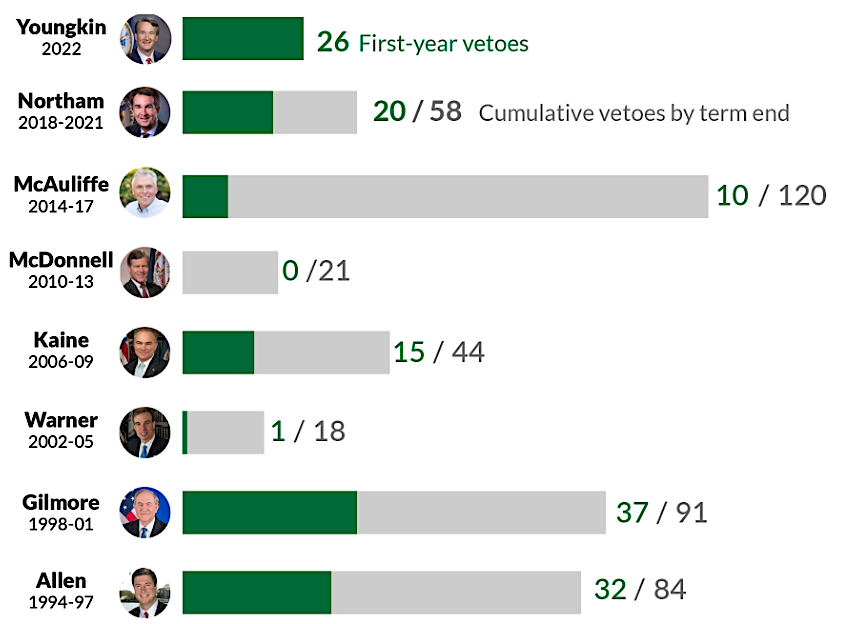

In 2018 and 2019, his first two years as governor, Gov. Ralph Northam dealt with a General Assembly in which Republicans controlled both the House of Delegates and the State Senate. He vetoed 54 bills.

In 2020, after the 2019 elections, Democrats were in control of both houses. Gov. Northam vetoed just four bills.

He blocked a proposal from the dairy industry that would have required all items labeled "milk" to come from mammals and not from almonds, soy, or other vegetable products. The other three dealt with the Affordable Care Act. After the three bills had been passed by the General Assembly with broad bipartisan support, the governor proposed amendments because he thought they might raise the cost of medical care for the poorest members of society. When the legislators rejected his amendments, Gov. Northam vetoed those three bills.15

for all four years he was in office, Gov. McAuliffe was a Democratic governor with a Republican-controlled legislature

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), First Year Vetoes

Governor Youngkin broke tradition with some of his first 25 vetoes in 2022. The General Assembly had passed duplicate versions of some bills, a technique that allowed members of the House of Delegates and the State Senate to claim they were responsible for introducing the same legislation. Governor Youngkin, a Republican, vetoed six bills that had been introduced by a Northern Virginia Democrat in the House of Delegates, while signing the equivalent bill introduced originally in the State Senate.

Youngkin vetoed nine of the ten bills introduced by the Democratic legislator, even though six of them had passed unanimously through both houses. By denying the Democrat the opportunity to claim credit, the governor sent a message but also exacerbated partisan tensions in the legislature.16

Both houses of the 2024 General Assembly sent 1,046 bills to Governor Youngkin, a Republican. He vetoed 153 bills while signing 777 bills and amending 116 bills. The relatively high number of vetoes reflected the partisan difference between the Executive and Legislative branches, after the results of the 2023 election switched the House of Delegates from Republican to a Democratic majority.17

The governor considered vetoing the budget, after the General Assembly had revised his proposal substantially and incorporated policies into funding which Governor Youngkin opposed. Another option was to use his line item veto power for appropriation bills and strike funding for specific proposals. The legal authority for line item vetoes of appropriation bills has been questioned, but both Republican and Democratic governors have used that power anyway.

Governor Youngkin chose to submit 233 specific budget amendments to undo policy and funding changes made by the legislators to his draft 2025-2026 budget. The one-day veto session scheduled for April 17 would not be sufficient to consider those complicated revisions.

In response, the House Majority leader said:18

Failure to adopt a budget before July 1 would force a shutdown of state government operations. Just the potential of such a failure would threaten the state's AAA bond rating and increase the cost of borrowing money.

In the end, leaders in the legislature and Governor Youngkin agreed to start over and draft a new budget. In choreographed moves, the General Assembly rejected all 233 budget amendments during the annual one-day veto session and the governor called a special General Assembly session to meet in May. In the intervening month, the legislators and governor agreed to negotiate their differences and draft a new FY25-26 budget. It passed in a one-day special session.19

Democratic Governor Ralph Northam vetoed 54 bills when Republicans controlled the General Assembly in his first two years - and just four bills in his third year, when Democrats were in control

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Gubernatorial Vetoes After Three Years

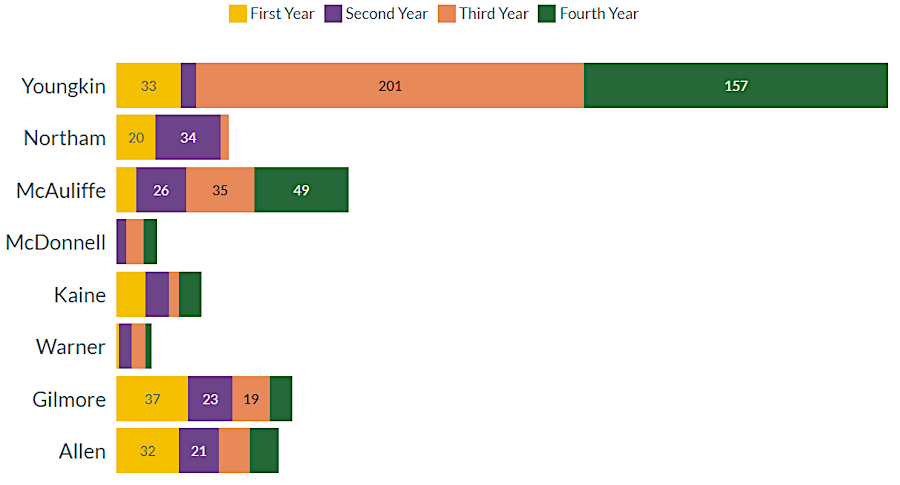

Despite the ability to compromise on the budget, Republican Governor Youngkin and the Democratic majority in the General Assembly were unable to reconcile many other differences. He ended up vetoing 201 bills passed by the legislature in the first session of the 2024 General Assembly. That surpassed the previous record of 120 vetoes by Governor Terry McAuliffe during his entire four years.

In 2022 and 2023, the Republican-controlled State Senate had blocked partisan "culture war" issues. In 2024 Governor Youngkin had to use his veto power to kill bills he opposed involving guns, birth control, clean energy, and state tax subsidies for Confederate heritage organizations.

Included in his list of vetoes was a bill authorizing "skill games," which allowed a form of gambling which generated significant revenue for mom-and-pop convenience stores. That bill had passed after much debate within both parties. Governor Youngkin did indicate he was willing to explore a new bill to regulate skill games, a bipartisan issue of great interest to business owners in rural Virginia localities represented by Republicans.20

Governor Youngkin vetoed 157 of the 916 bills approved by the 2025 General Assembly. Throughout his four year term, all of his vetoes were sustained by the legislature; none were overridden. The primary challenge for the legislators in 2025 was how to deal with amendments proposed by the governor to 159 bills. Refusing to accept an amendment could result in the bill being vetoed, while accepting the amendment could dilute the impact.

2025 was the governor's last year in office. Amendments that he proposed in 2022 in his first year in office had been harder to oppose, since there would be no chance to overturn a veto for four more years.

The math was different in the governor's last year in office. Democrats who anticipated retaining control of the House of Delegates and winning the governor's race in the November 2025 election were more willing to reject an amendment. The governor's veto would create only a one year delay; passage of the bill without an amendment would be possible in 2026:21

The Democrats gambled that they would have 51 seats in the House of Delegates in 2026 and that their candidate, Abigail Spanberger, would be the first woman elected governor:22

the record number of vetoes by Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin reflect both his combative approach and having a Democratic-controlled legislature for four years

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Vetoes by Year: 2025

In the 2025 General Assembly the Democrats clearly lacked the 2/3 majority required to overturn the governor's vetoes; they had only a slim 51-49 majority in the House of Delegates and a 21-19 majority in the State Senate. They forced votes - and lost each time - on 15 bills in the House of Delegates. That ensured recorded votes which could be used in the 2025 campaigns for the November election. There was no political advantage for the Democrats to debate individual bills in the State Senate. Those members were serving four-year terms, and the next election for those 40 seats was not until 2027.

The veto override attempts in the House of Delegates were recognized as political theater. The primary question for the April 2, 2025 one-day "reconvene" meeting of the General Assembly was how many of the governor's 205 specific amendments to the FY2025-2026 budget would be accepted, and similarly for the 159 bills where the governor submitted amendments rather than a veto.

The legislature made 515 amendments to the two-year budget, which had been adopted in 2024 and went into effect on July 1, 2024. The governor proposed 205 amendments and made an additional eight line item vetoes. The House of Delegates ended up accepting 41 budget amendments and rejecting ("passing by") 164. Of the line item vetoes, six were sustained and went into effect, but two were ruled to be out of order by the House Speaker and voided by that parliamentary action. The State Senate accepted 33 of the governor's amendments, so in the end 172 were rejected.

On four bills dealing with health care, enough Republicans joined with Democrats in the House of Delegates to create a 2/3 majority to override the governor's veto. Voting to override the veto of their Republican governor may have immunized those Republican delegates against partisan attacks in the upcoming election. They also knew their votes were just symbolic, since the 49 Republicans in the State Senate would provide enough votes to sustain the vetoes.

The governor had the option of vetoing the entire budget bill because 84% of his amendments had been rejected, but that would have been a drastic response and would have killed the 33 amendments which were accepted. He also had the ability to exercise line item vetoes in the budget, which would eliminate funding for items which he was unable to amend.23

Gov. Youngkin returned 91 bills to the General Assembly in 2025 with proposed amendments. He also recommended 205 changes to the budget bill.

The legislature supported him on 69 of the bills, plus 33 of the budget revisions. After the "reconvene" session, the governor had the option to veto the other 91 bills where his amendment was rejected or to allow the bills to go into effect without his amendments. He ended up vetoing 53 of the 91, and allowed 38 to become law without his amendments.

He also made 37 line item vetoes to the budget bill. Those line item vetoes reduced expenditures in the state budget by $900 million. In most cases, Gov. Youngkin blocked funding for capital improvements. The $900 million was part of a $3.2 billion surplus that was appropriated in the bill. The vetoes left $900 million unspent, to serve as a reserve in case state tax revenues dropped in an economic downturn/recession during the first year of the Trump Administration.

For the 53 bills and the 37 line items that he vetoed, legislators expected they had to wait until the 2026 General Assembly to try again.24

However, the Clerk of the House of Delegates used his authority as "Keeper of the Rolls of the Commonwealth" to reject three budget amendments. According to rulings by the Supreme Court of Virginia, particularly the Brault v Holleman case, Article V in the state constitution requires that a veto of an item in the budget bill must eliminate both the funding and whatever conditions were attached to the funding:25

The key language in Article V Section 6 of the Constitution of Virginia was:26

The clerk, Paul Nardo, determined that for three items, the veto did not address the appropriation as well as the language putting conditions upon expending the money. The failure to veto the funding as well as the conditional language would, in the clerks judgment, permit spending for a purpose beyond what the legislature has authorized. Republican legislators had been responsible for selecting the clerk, who had used the same constitutional provision to block vetoes from Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe in 2014 and 2016.

The clerk's actions reflected institutional conflicts between the authorities of the legislative branch vs. executive branch, rather than simple partisan politics. His actions in 2025 blocked the vetoes of a Republican governor from taking effect. Nardo relied upon the division of powers in the state constitution:27

Governor Youngkin said he would ignore the clerk's action. State agencies would act as if the vetoes were in effect. The Virginia Health Care Association-Virginia Coalition for Assisted Living filed a lawsuit to force the Department of Medical Services Assistance to ignore the governor's direction and distribute Medicaid funding to support increased staffing in nursing homes.

The Democratic Speaker of the House of Delegates, which had standing to sue because budget bills originate in that house, had chosen not to sue. He decided to use a political rather than legal approach, waiting until the next governor took office. Speaker Don Scott anticipated that the Democrats would win that race and retain control of the House of Delegates in the November 2025 elections. He said about Governor Youngkin28

The Republican/Democratic split between the governor and the legislature was one reason for the high number of vetoes by Governor Youngkin. By the end of his term, he had vetoed 399 bills. In his first two years when Republicans controlled the House of Delegates, he vetoed 41 bills. In 204-2025, when Democrats controlled both houses of the General Assembly, he vetoed 358 bills.

Democratic leaders claimed that the governor's approach was a key factor. Senate Majority Leader Scott Surovell said at the end of the 2025 "reconvene" session:29

In contrast, Gov. Baliles never vetoed a bill. During his entire 1986-1990 term, fellow Democrats had full control of the General Assembly. Baliles still had policy differences with legislators, especially regarding transportation funding. Those differences were resolved before bills were passed, not afterwards through a veto.

As described by one political insider in 2025, after Youngkin had already set a record with the number of his vetoes:30