Riverhill Farms in the Shenandoah Valley has been producing biodiesel since 2010

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Riverhill Farms in the Shenandoah Valley has been producing biodiesel since 2010

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Liquid biofuels are manufactured at several small refineries in Virginia. For example, since 2010 Riverhill Farms near Port Republic in Rockingham County has been creating biodiesel. It's source material was originally soybeans, and then canola grown on that farm. In 2019, costs to produce that locally-generated biofuel was just $1/gallon.1

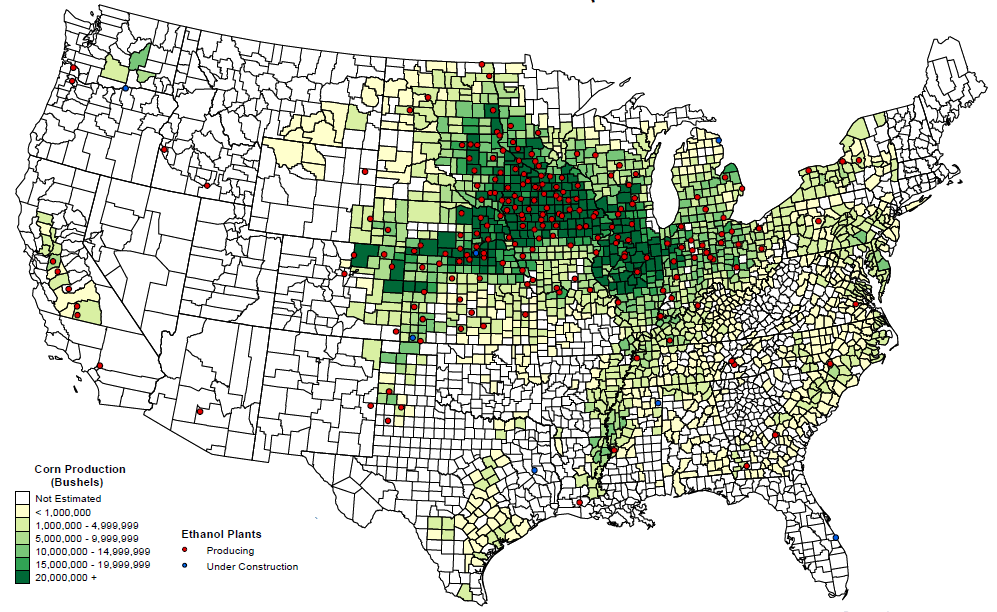

The first large-scale ethanol plant in Virginia started operating in 2014.

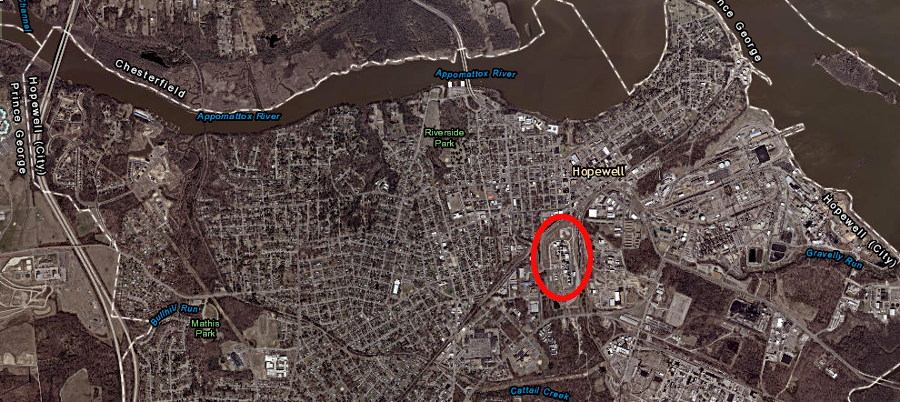

In 2011, Osage Bio Energy completed a roughly $200 million ethanol production facility to make 65 million gallons of ethanol per year in Hopewell from barley. Perdue Grains contracted with Virginia farmers to grow barley as the feedstock to be converted into ethanol. Osage Bio Energy planned to convert the starches in the barley grains into ethanol, while the hulls of the grain would be burned for energy and the dried distillers grain (DDGS) residue would provide a protein-rich food supplement for livestock.

The facility was expected to require 300,000 acres to grow 28 million bushels of barley. The Hopewell plant, the first ethanol production facility on the East Coast, was predicted to create a $100 million demand for a winter cover crop that would simultaneously enhance water quality, by utilizing nitrates in the soil that otherwise washed into the Chesapeake Bay.2

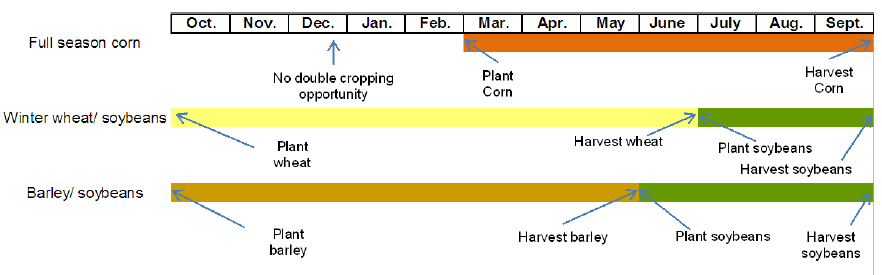

Osage Bio Energy encouraged Virginia farmers to grow barley for biofuels rather than corn or wheat - double cropping barley and soybeans provided a longer growing season for soybeans, enabling a higher yield

Source: Osage Bio Energy (presentation to Virginia Commission on Energy and Environment, October 14, 2008)

The completed plant never opened as planned in May 2011, apparently because the investors (First Reserve, an equity firm in Connecticut) were unable to get a bank to provide operating capital. To maintain its reputation within the farming community, Perdue absorbed a financial loss and bought the 2011 crop of barley anyway. The City of Hopewell, which had anticipated $5 million/year in tax revenues, had to sue First Reserve to collect some of the promised financial benefits.

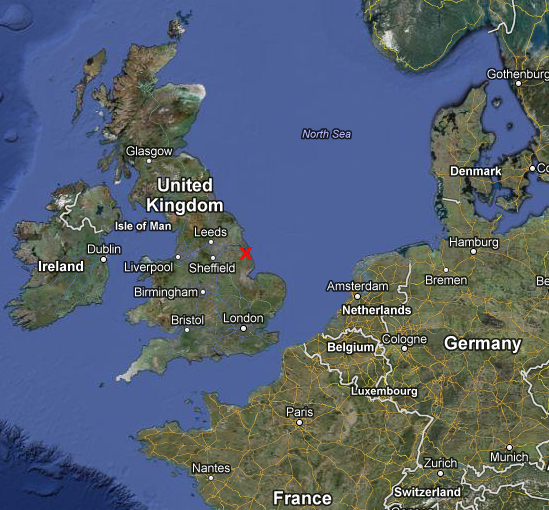

In 2013 the equipment was sold to a company that planned to dismantle the plant and move the equipment to Northeast Lincolnshire in England. In 2014, the Hopewell City Council agreed to match a $250,000 grant from the Governor's Agriculture and Forestry Industries Development Fund, and the state committed up to $1.5 million/year in subsidies through 2017.

That commitment convinced the British company Vireol to start operations at the ethanol plant in Hopewell, rather than move the equipment. Up to 70 jobs were created when the plant opened in 2014, and Virginia farmers gained a customer interested in purchasing over $30 million of corn, wheat and barley each year.3

equipment at the ethanol plant in Hopewell could have been shipped to the village of Great Coates in Northeast Lincolnshire

Map Source: Google Maps

Biofuels is a high-risk business. Expenses are guaranteed, but profits are not. In 2015, Vireol stopped operating and was forced to declare bankruptcy. Gas prices had dropped 35%, and the company was behind in paying the local property and the machinery and tools (M&T) taxes. Green Plains, a large ethanol producer based in Nebraska, acquired the Hopewell facility, spent $10 million to upgrade it, and restarted operations in 2016.

Rather than rely upon barley, Green Plains announced plans to purchase 62,000 bushels of corn annually. As the plant manager described the decision to switch from barley to corn:4

the biofuels plant producing ethanol in Hopewell

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Green Plains upgraded the Hopewell plant so it could produce as much as 60 million gallons a year of ethanol. However, in 2018 the company closed the facility due to reduced demand for ethanol used as a gasoline supplement. In the decommissioning process, Green Plains shipped equipment that could be re-used to the 13 other ethanol production plants owned by the company.

The Hopewell facility is the only facility in Virginia that has produced ethanol for sale in large quantities. The product was sold to gasoline terminal operators in Richmond/Petersburg. They blended the ethanol with gasoline before it was trucked to retail outlets for sale to customers filling gas tanks of their cars. Green Plains also sold the residue from the corn, distillers grain, to local farmers for livestock food.

Even without a large ethanol facility operating in Hopewell, Virginia farmers still can grow barley or corn for ethanol and soybeans for biodiesel. Hampton Roads ports offer easy transportation options to export biofuels, and the Virginia Biodiesel Refinery in West Point has been operating since 2003. West Point, Yorktown, Craney Island, and Portsmouth are likely candidates for future ethanol/biodiesel refineries producing fuel from renewable resources, at a scale large enough for barge export.

Virtually any location near an existing petroleum tank farm than blends gasoline with ethanol is suitable for a small-scale refinery producing E-10, E-15 or E-85 gasoline. Small projects owned by local farmers, cooperatives, or business leaders are also economically feasible.

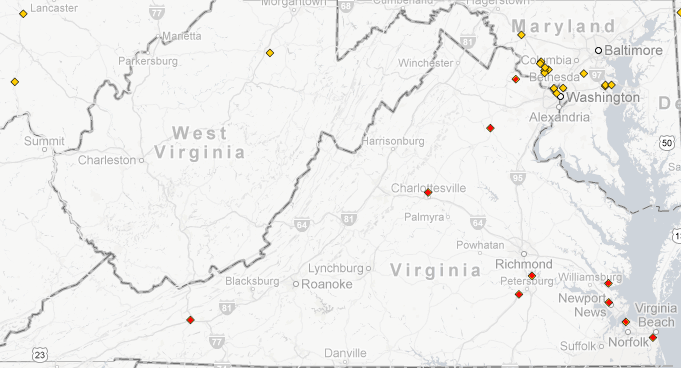

By 2016, there were six plants across the state producing biodiesel from soybeans, canola, or waste grease from restaurants and blending it with petroleum-based diesel. By 2017, Wholesome Energy in Edinburg had stopped operating. The remaining five were still active in 2019:5

- RecoBiodiesel (City of Richmond)

- Red Birch Energy (Bassett, Henry County)

- Shenandoah Agricultural Products (Clearbrook, Frederick County)

- Synergy BioFuels (Pennington Gap, Lee County)

- Virginia Biodiesel Refinery (West Point, King William County)

- Wholesome Energy (Edinburg, Shenandoah County)

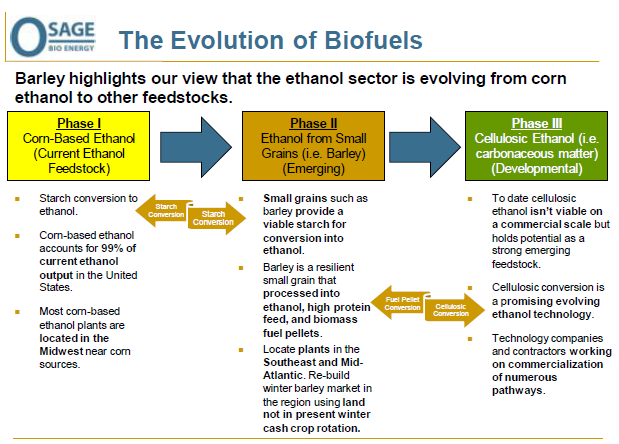

Osage Bio Energy expected barley to be an interim source of biofuels, until switchgrass or other sources of cellulose could replace it

Source: Osage Bio Energy (November 18, 2009 presentation to Mid-Atlantic Crop Management School)

Since 2008, Red Birch Energy in Bassett (Henry County) has been buying canola seeds to create biodiesel sold at the company's Country Market Biodiesel Truck Stop. Canola is purchased from North Carolina suppliers, as well as from farmers in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. The canola is converted into B20 (20% from canola, 80% diesel refined from petroleum) and B100 biofuel in a $1 million refinery.

The project was stimulated in part by the truck stop's difficulty in getting fuel after Hurricane Katrina forced refineries on the Gulf Coast to close in 2005. The result was the first closed-loop biofuel delivery system in the country, where the owner could say "We grow it, we make it, we sell it, all in one community."

To facilitate using the glycerin residue from refining canola to generate electricity and power the truck stop's operations, the Biomass Energy Grant Program of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided $750,000 (of the $1.2 million project) in Federal funds to Red Birch Energy.6

perhaps appropriately, Red Birch Energy is located next to two fast food restaurants and a gas station

Source: GoogleMaps

The Virginia Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission is providing state-sponsored financing in the former tobacco growing areas, in hopes of creating jobs for farmers and in refineries that create biofuel. The commission funded an assessment of nine potential biomass projects in Southside Virginia and ten sites for such projects in Southwestern Virginia, looking beyond biodiesel to the option of using cellulose-based material to generate electricity.

The top two opportunities identified were for a biomass-fueled heating system to service 20 buildings at Charlotte Court House, and a similar system to heat four facilities in the Town of Independence (Grayson County). The projects would be cost-effective if the biomass operation was large enough to generate surplus electricity to be sold to the local utilities, as well as heat for the buildings.7

In 2012, the Virginia Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission did provide $2.7 million to Tyton BioSciences in Danville, to create ethanol and biodiesel directly from tobacco. Farmers typically grow only 6,000 tobacco plans/acre, but if energy feedstock was the goal then farmers would grow 80,000-100,000 plants/acre. The company's founder chose Danville for a reason:8

In 2013, Piedmont BioProducts received $5.3 million in state grants to build a biodiesel refinery in Gretna. The goal was to convert perennial grasses such as switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) into biodiesel, creating jobs in the farming community to grow the feedstock and jobs at the refinery to create the biodiesel.9

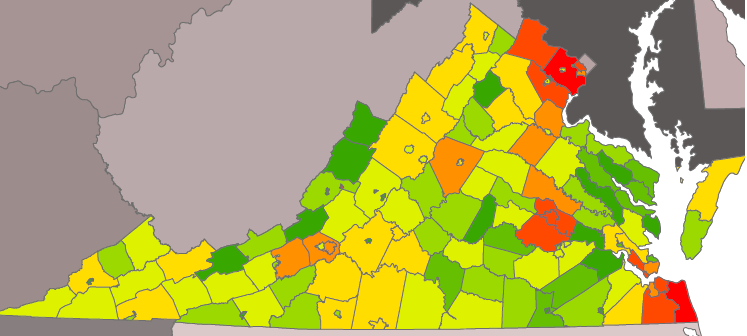

availability of "yellow grease" from commercial food operations reflects where population is concentrated in Virginia - Northern Virginia, Hampton Roads, and Richmond area

Source: Preliminary Residual Biomass Inventory for the Commonwealth of Virginia (p.59)

Another oil refining opportunity is to recycle waste cooking oil and fats ("yellow grease") from restaurants, creating biofuel for use in cars and other machinery. In 2007, the Virginia Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission awarded Synergy Biofuels a grant to fund half of a new $1 million biodiesel fuel production facility in Lee County, in part because "There is a plentiful supply of used vegetable oil around the neighboring areas."10

Darton Environmental, a small garage-based business in Bedford, expanded in 2013 and established a new refinery at an industrial site to process grease/oil generated at food establishments around Roanoke and Lynchburg. Shenandoah Agricultural Products in Frederick County has established its own closed-loop system. It raises canola and produces edible fryer oil, which is sold to local restaurants. The waste oil is collected from those restaurants and used to produce biodiesel, which then fuels operations on the farm that raises the canola.11

not every place called a "refinery" processed petroleum - the Capitol Refinery, located where the Pentagon now sits, was built to process cottonseed oil into 1,000 barrels/day of salad/cooking oil12

Source: Library of Congress, Capitol Refining Co. plant

Valley Proteins, headquartered in Winchester, produces lipids that are used as an animal food supplement. Today it converts used restaurant oil and animal fats into biofuel as well.

Since 1949, Valley Proteins has recycled waste oil from restaurants, fat trimmed off animal carcasses at meat processing plants and grocery stores, dead horses, and remains of chickens and turkeys not suitable for processing into human food. At one time, the company even "rendered" pets collected from veterinarians, heating carcasses in boilers to extract the reusable fats, oil, and grease. The biofuel product was used at the company's processing plants and sold as an alternative to No. 2 and No. 6. fuel oil.

After the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned the use of brain/spinal cord tissue from older cattle for production of animal feed to reduce the risks of "mad cow disease" (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), recycling of cows at rendering plants cut back sharply. At Valley Proteins, processing of euthanized animals ended in 2019, after pentobarital from some euthanized horses ended up as an "unapproved drug" contaminating a batch of final product.13

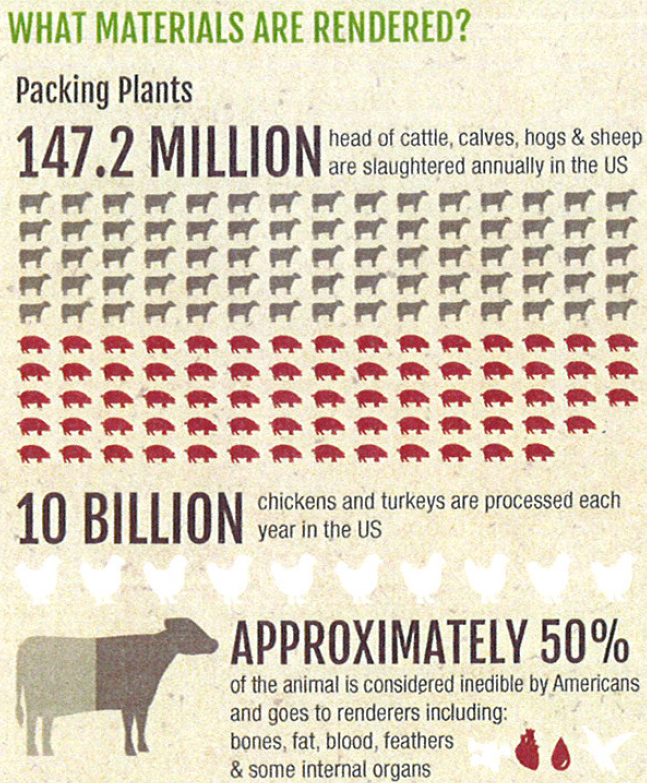

renderers convert animal carcasses into edible oils, proteins, and biodiesel products

Source: Valley Proteins, Rendering Is Recycling

Valley Proteins used to have essentially a monopoly in Northern Virginia and Richmond, as well as in the Shenandoah Valley. The company charged restaurants for removal of waste oil, since municipal solid waste landfills will not accept liquid waste, so the raw material was essentially free.

That created opportunities to generate profits from waste collection services for nearly 50,000 restaurants, plus profits from the sale of the processed "yellow grease" used as animal feed. Market demand has varied, and smaller companies who enter the waste oil collection business typically disappear during the downturns. After other biofuel companies entered the business, such as Greener Oil in Richmond in 2008, Valley Proteins was forced to compete in order to maintain its sources of supply.

At times, demand gets high enough for restaurants to charge for their waste oil, and "rustling" can become a problem. In 2012, thieves were getting $3 per gallon. During that peak market, Valley Proteins bought over 1,000 locks monthly to re-seal dumpsters, after thieves cut off the old locks. In some cases, they bypassed the locks and used torches to cut into the storage tanks in order to drain the oil.

In 2019, there was another surge of thefts in Northern Virginia. The region was attractive to waste oil theft because many restaurants were located close to each other, providing a target-rich environment. One man was caught draining 150 gallons at a Burger King in Annandale Shopping Center. A Valley Proteins lawyer reported that the company had lost $5 million in stolen oil in 2015, plus another $1 million that year for re-securing waste oil storage tanks. Thieves were thought to make as much as $10,000 per night.14

The governor of Virginia optimistically stretched the definition of "biodiesel" in 2014, when he announced plans by Appalachian Biofuels LLC to open a new biodiesel production facility in Russell County.

Appalachian Biofuels proposed to use enzymes from an Israeli company to reprocess used oil and oil products as the feedstock to produce "biofuel to be blended with petroleum diesel fuel as mandated by the federal government." The process did not involve using plant material to create fuel, but the state claimed a green energy company would produce an alternative fuel.

The company committed to make a $3.5 million private investment and create 40 jobs, and obtained a $565,000 grant from the Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission. The facility never opened, after oil prices dropped significantly. Appalachian Biofuels LLC repaid $355,000. The company's Chief Executive Officer convinced the commission to waive its claim on the remaining $210,000, citing his success as the Vice-Chair of the Virginia Israel Advisory Board in attracting other investments to the region.

An Inspector General report concluded in 2020 that the deal to substitute other activities for repayment of the Tobacco Region Opportunity Fund (TROF) grant had never been approved, as required, by the Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission. The executive director of the commission had authority to negotiate grants under $1 million, and claimed responsibility for negotiating an alternative to repayment of the $210,000.15

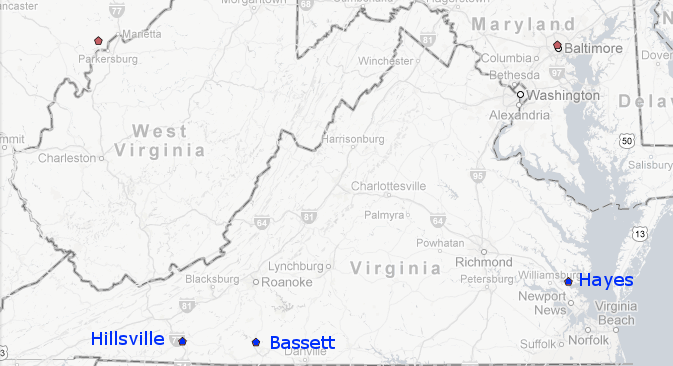

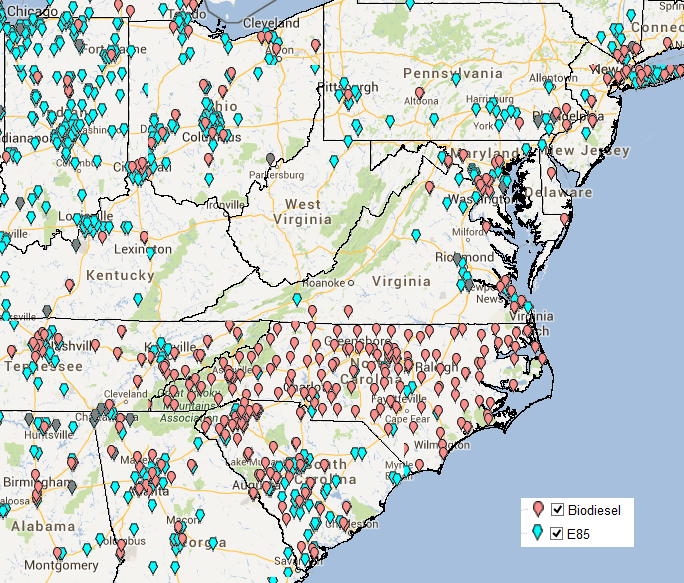

in early 2013, Virginia had 3 biodiesel (B20 and higher) fueling stations in Hayes (Gloucester County), Basset (Henry County), and Hillsville (Carroll County)

Source: US Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center

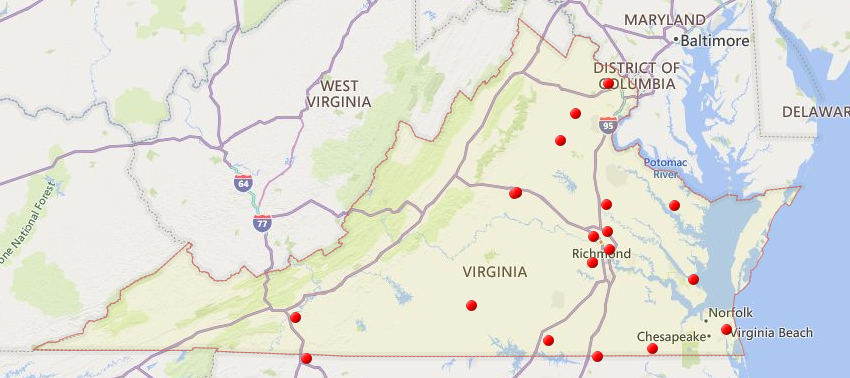

by 2020, Virginia had 18 biodiesel (B20 and higher) fueling stations

Source: National Bi

odiesel Board, Retail Map

Production of ethanol and biodiesel from food crops, such as corn, canola, and barley, raises demand and thus the prices paid to farmers. Virginia adopted a voluntary Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) in 2007, but the Federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) established a minimum volume of renewable fuel to be used annually for gasoline/diesel.

soybeans are crushed at Riverhill Farms to extract the oil used for biodiesel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Alternative energy powers a Virginia farm

The proposed increase from 10% volume ethanol (E10) to 15% volume (E15) has triggered concerns that prices will stay so high that the livestock industry in Virginia and other southeastern states will be damaged. Concerned that the cost of ethanol was too high to justify an E15 Renewable Fuel Standard, Rep. Robert Goodlatte introduced legislation to repeal or modify the Federal Renewable Fuel Standard mandate.16

in early 2013, Virginia had 10 E85 fueling stations

Source: US Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center

by 2020, E85 fueling stations were common across Virginia

Source: US Department of Energy, Alternative Fueling Station Locator

Goodlatte represented the 6th District, including the most productive livestock operations in the Shenandoah Valley, and Virginia does not produce enough corn to support its livestock industry. The Virginia Grain Producers Association claims the state imports 90% of its animal feed, while most Virginia-grown corn is exported. A 2012 study by an economist associated with the poultry industry claimed:17

However, a separate study by the National Corn Growers Association reached a different conclusion. That study argued that beef and dairy farm profits have climbed since RFS expansion, though the 12 states analyzed did not include any Mid-Atlantic or Southeastern states (except Florida).18

Whatever the impact of the Renewable Fuel Standard on food prices or profits of different sectors of the agricultural industry - if ethanol remains more expensive than gasoline, and the Federal mandate for adding ethanol to transportation fuels is lowered, then the potential for another ethanol refinery in Virginia (in addition to the one at West Point) would drop until cellulosic-based facilities can replace those using food crops.

as of March 8, 2012, ethanol plants were located primarily near corn producers

Source: US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Production by County and Location of Ethanol Plants (2011)

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) could be grown for a profit on agricultural land not suitable for food crops (too steep, too sandy, too poor in nutrients). Like any crop, switchgrass would have to be harvested, digested, and converted into ethanol. Switchgrass is a native species, but now rare due to patterns of past grazing:19

In the future, tissue culture technology might facilitate production of genetically-identical plants to grow non-native grasses such as (Miscanthus genus), giant cane (Arundo donax), or other species for conversion into biofuels. The Institute for Advanced Learning and Research in Danville, working with the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Virginia Tech, has developed micropropagation technology that could result in commercial-scale production of biorenewable feedstock.20

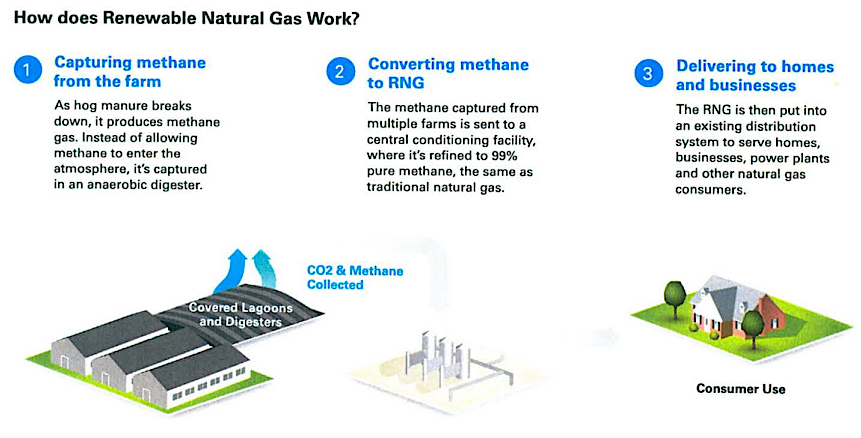

Virginia's first large-scale biogass facility was approved in a 2-1 vote by the Surry County Board of Supervisors in June, 2022.

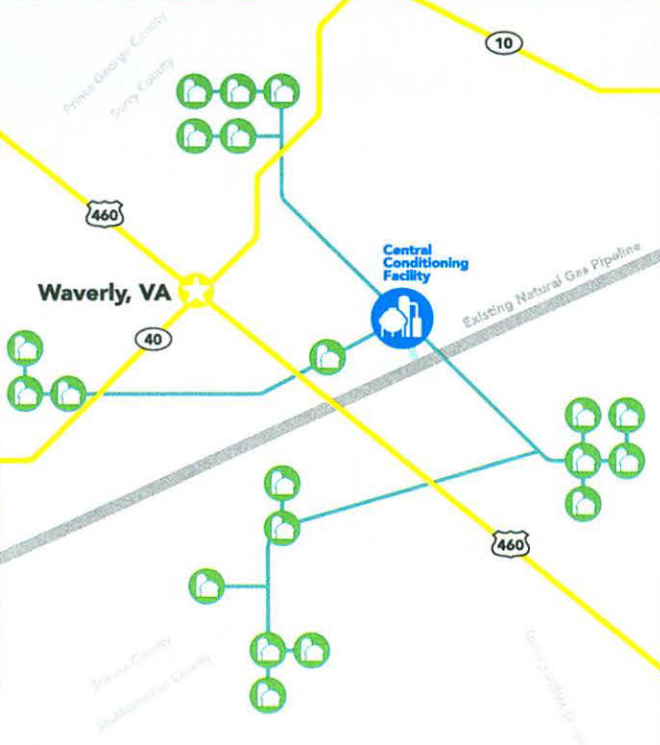

Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy partnered in 2018 to create Align Renewable Natural Gas, to convert methane from hog manure into pipeline-quality natural gas. At the time, Dominion Energy was championing construction of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The biogas project was one response to concerns about how expansion of fossil fuel use would impact climate change.

The project included constructing a 65-mile network of pipelines from 20 farms where hogs were concentrated to the biogas production site at Waverly. In contrast to the challenges faced by the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Mountain Valley Pipeline projects, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission unanimously approved pipeline crossings of Blackwater River, Seacock Swamp, and Assamoosick Swamp, using the horizontal directional drilling method in Surry, Southampton, Sussex, and Isle of Wight counties.

capturing and burning methane was projected to provide climate change benefits

Source: Align Renewable Natural Gas, Align Renewable Natural Gas (Align RNG) Partnership in Virginia

The gas from hog manure lagoons was 60-65% methane and 30-35% carbon dioxide, with enough hydrogen sulfide to provide a distinctive smell. The lagoons would be capped in order to trap the gas emissions in digesters. After the gas was transported via pipeline to a site near Waverly, methane would be separated and inserted into an existing Columbia Gas of Virginia pipeline. The carbon dioxide would be released into the atmosphere. Some of the sulfur would be captured for reuse, and the remaining hydrogen sulfide would be incinerated to convert the odiferous gas into sulfur dioxide before release.

Customers burning the methane would later generate more carbon dioxide, but the project could claim greenhouse gas emissions would be reduced overall. Methane causes greater global warming impacts than carbon dioxide. Align claimed that the benefits from converting methane would be equivalent to planting 1.5 million new trees each year. One news story described the project in the headline as:21

Align Renewable Natural Gas planned 65 miles of pipeline to capture methane from 20 hog farms near Waverley

Source: Align Renewable Natural Gas, Align Renewable Natural Gas (Align RNG) Partnership in Virginia

The dissenting member of the Surry County Board of Supervisors lived near the proposed project. After the vote, he sued the county based on a claim that the Planning Commission had not followed procedures according to legal requirements. He was unable to sue the county and simultaneously serve as elected supervisor unless the other two members of the Board authorized his lawsuit. When they declined, he resigned from the board.22

Starting in 2019, the Western Virginia Water Authority planned a facilities upgrade that included the ability to trap methane emissions. The 2022 General Assembly passed the Virginia Energy Innovation Act which authorized gas capture as an alternative to wastewater treatment plants burning waste methane in a flare stack. The utility then partnered with Roanoke Gas to send the methane to the gas utility's 63,000 customers through the natural gas pipeline network.

As part of the upgrade, Roanoke Gas would invest over $7 million in the digester gas conditioning system so the raw emissions that were 64% methane could be processed into a product that was 99% methane. A Roanoke Gas executive commented:23

The State Corporation Commission approved the project in March, 2023. In a hearing at the State Corporation Commission, Appalachian Voices had objected to including that investment in the gas company's rate base. Appalachian Voices claimed the environmental benefits of the project were greatly overstated, and that the state's review of the project had been inadequate. Its lawyer said:24

Appalachian Voices was more successful in its opposition to proposed legislation in the 2023 General Assembly declaring coal bed methane captured from mine ventilation holes to be "renewable" energy. Such classification could allow coal mines to sell Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) and thus incentivize more coal mining. In the end, the bill language was changed to direct the Department of Energy just to evaluate policy options, and Appalachian Voices withdrew its opposition.25

Fast food restaurants, which once paid haulers to remove used cooking oil as a waste product, now can sell that material as a source of energy. Carbon intensity is low and processing costs are high, but customers sensitive to climate change value "green" energy sources. The carbon footprint of "sustainable diesel" created from hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) is about 20% of the impact of the "dinosaur oil" produced in standard refineries.

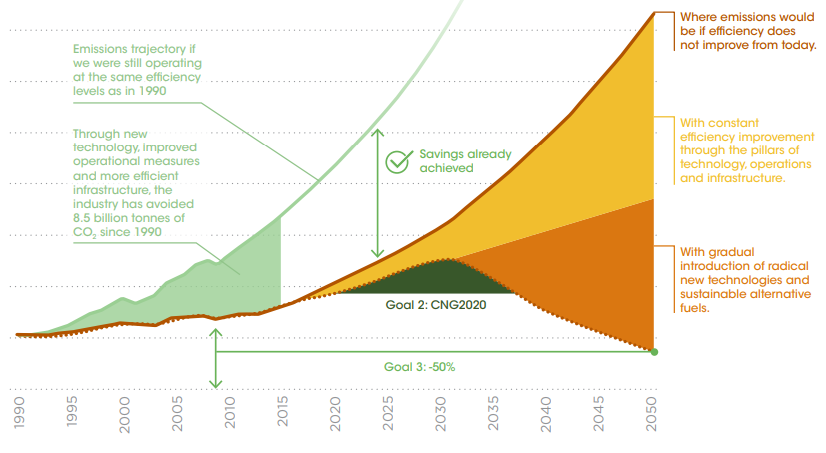

The aviation industry could become carbon neutral by 2050 by using carbon offsets to mitigate the continued use of petroleum-based fuels, or by creating electricity-based aircraft engines. Another alternative is to create Sustainable Aviation Fuel to replace jet fuel. Airplane travel creates about 3% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Reprocessed cooking oil, hydrotreated esters and fatty acids (HEFA) and hydrotreated vegetable oils (HVO), is authorized for use in existing jet engines but costs 3-6 times the equivalent of petroleum products. HEFA/HVO biorefineries creating renewable diesel must do extra processing to creating bio-aviation gas.

In 2024, the US Department of Energy committed $3 billion to support production of Sustainable Aviation Fuel through conversion of vegetable oils and leftover animal fats and greases at one facility in Montana, and creation of ethanol from corn at another operation in South Dakota.26

the aviation industry plans to be carbon neutral by 2050

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Biojet Fuels (Figure 1)

Thanks to widespread use of cooking oil to make French fries and hamburgers in restaurants, biodiesel is far more available than hypothetical alternatives. As a result of demand, theft of grease and oil from the storage drums behind restaurants is a common problem for biodiesel companies.

Thieves used crowbars to open containers behind restaurants and siphon out the now-valuable "waste." Darton Enterprises in Waverly lost thousands of dollars in used oil to thieves in early 2023. The owner of the company complained:27

By 2030, 10% of jet fuel is predicted to be Sustainable Aviation Gas. Green hydrogen may be a fuel for the future, but new engines will need to be designed and manufactured before hydrogen will become practical. As described in one 2023 news story:28

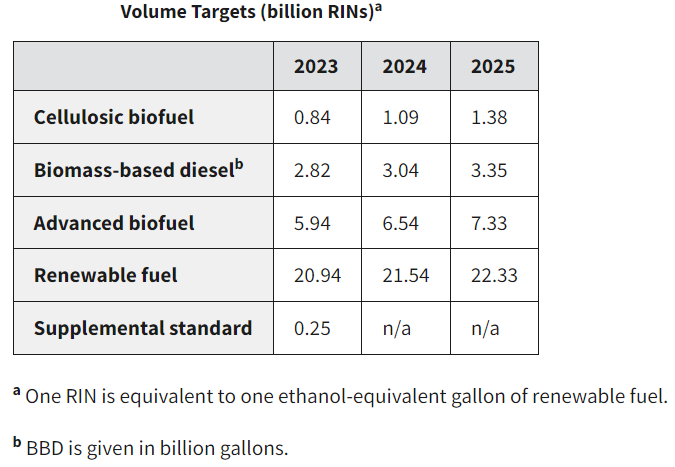

Federal Renewable Fuels Standards are set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The standards for 2023–2025 included a court-ordered supplement for 2023, but that was a one-time requirement.29

In 2024, Vanguard Renewables began constructing a biogas digester at Oakmulgee Dairy Farm in Amelia County. Manure from 300 Holstein cows, plus waste plant material, was to be converted into methane. AstraZeneca planned to purchase the "renewable natural gas" to fuel pharmaceutical production facilities. Vanguard Renewables launched a project earlier in the year with Prince Michel Vineyard & Winery in Madison County to produce biogas and fertilizer from waste plant material.30

The Hampton Roads Sanitation District invested $30 million to capture methane bubbling out of wastewater being treated at the Atlantic Treatment Plant and burn the gas to generate electricity. It was designed to eliminate the flaring of the biogas, which converted the methane to carbon dioxide (a less potent greenhouse gas) but provided no economic benefits.

The utility partnered with Virginia Natural Gas, which financed the project. Utility customers will pay an extra $0.40/month on their sewer bills to cover the costs. The extra charge had been authorized by the General Assembly when it passed the Virginia Energy Innovation Act of 2022.31

The Southeastern Public Service Authority (SPSA) also found a private partner to upgrade its biogas reuse at the regional landfill in Suffolk. Terreva Renewables invested $25 million to convert landfill emissions into renewable natural gas for injection into the nearby TC pipeline. Previously, the landfill's biogas (with minimal processing) had been burned on-site to generate electricity.32

Renewable diesel and Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) biodiesel both start with organic fats and oils, but different production provcesses generate distinctly different products.

To produce biodiesel, organic fats and oils are heated in a reactor and then mixed with methanol and base catalysts. The final producr includes oxygen, so it can corrode storage tanks and be subject to microbial fouling. Biodiesel begins to crystallize at 34° compared to 16° for regular petroleum diesel, so it is not sold to end customers as B100 (100% biodiesel). Biodiesel is blended with petroleum diesel and sold as B5 (5% biodiesel) and B20 (up to 20% biodisel).

Renewable diesel a hydrocarbon (with carbon and hydrogen, but no oxygen) produced by a refining process very similar to refining crude oil. The final product can be used as a simple alternative to petroleum diesel, though it has 4% less energy by volume. Based on Renewable Fuels (RFS) mandates to use minimum quantities of biomass-based diesel, investments to alter refineries to produce renewable diesel increased substantially prior to the second Trump Administration in 2025.33

As of 2025, Virginia produced only biodiesel. There were no renewable diesel refineries within the state.

the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets national Renewable Fuels Standards

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Final Renewable Fuels Standards Rule for 2023, 2024, and 2025

switchgrass (Panicum Virgatum) is a native species in Virginia that could become a source for ethanol

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Switchgrass - Panicum virgatum L.

a 2013 map of Alternative Fuel Stations shows wide availability for customers throughout North/South Carolina compared to narrow availability in urban areas of Virginia

Source: US Department of Energy - National Renewable Energy Laboratory, BioFuels Atlas