Oil Refining in Virginia

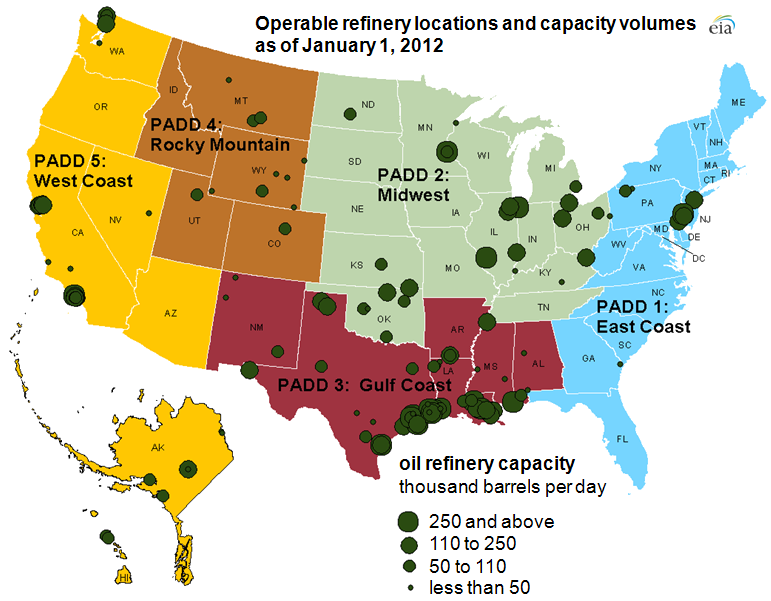

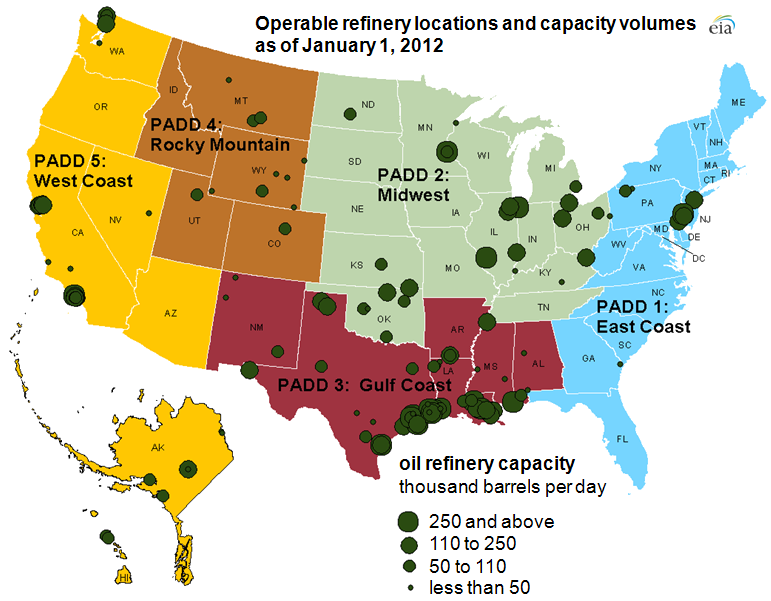

refineries on the East Coast are clustered on Delaware River and northern New Jersey, with no refineries operating now in the Chesapeake Bay watershed

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Much of the country's refinery capacity is concentrated along the Gulf Coast

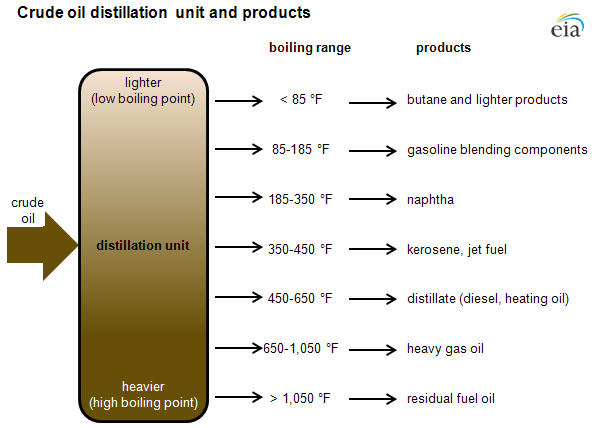

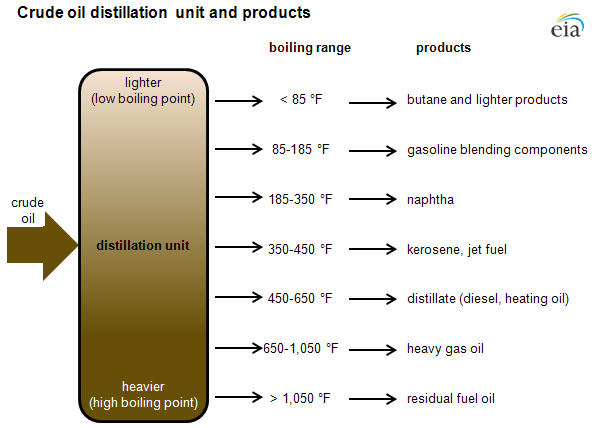

Refining crude oil is similar to making whiskey by distillation. A fluid is heated and the resulting gases are condensed. In whiskey making, the alcohol boils before the water, so a distiller manages the temperature carefully to capture the condensed alcohol without too much water.

In oil refining, crude oil is boiled (carefully...). The vapors are then distilled into various products. The complex chemistry of the hydrocarbon liquids requires careful manipulation of pressure as well as temperature, plus the use of catalysts to break long-chain molecules into high-value gasoline/jet fuel and to minimize the residue of low-value bunker fuel/asphalt.

at a refinery, crude oil is vaporized under atmospheric pressure or a vacuum - and then gases with different molecular compositions condense at different temperatures, resulting in different products

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Crude oil distillation and the definition of refinery capacity

Virginia once had three small refineries processing crude oil, but all are now closed. Over half of the refineries in the United States have closed since 1982, and only 141 remained in 2016. In Petroleum Administration for Defense District 1 (PADD 1 is the East Coast from Maine-Florida, including West Virginia but excluding Ohio), the 27 refineries operating in 1982 declined to just nine in 2016.

The South Philadelphia Refinery, the largest on the East Coast, closed after an explosion in 2019. By 2022, there were just seven refineries in PADD 1 - one in West Virginia, one in Delaware, two in New Jersey, and three in Pennsylvania. That was still enough to keep gasoline and diesel prices lower in on the East Coast than in California. The Colonial Pipeline reaches the refineries in Delaware and New Jersey plus one in Pennsylvania, but California lacks pipeline capacity. The inability to transport crude oil cheaply by pipeline to California refineries is one reason why fuel prices are typically significantly higher in that state.1

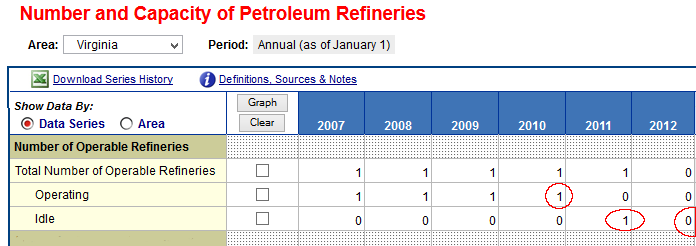

Since 1990, the tiny Primary Energy Corporation refinery in Richmond closed, reducing capacity by 6,100 barrels/day. The last oil refinery that operated in Virginia, at Yorktown, could supply central Virginia, Hampton Roads (including the US Navy), Washington DC, and Baltimore by barge and truck. It could even barge products to the Philadelphia/New York region when justified by market conditions (such as the temporary shutdown of a refinery in that area for maintenance). The Yorktown facility could refine as much as 66,000 barrels a day of crude oil into products such as gasoline, diesel, home heating oil and propane, before it closed at the end of 2011.2

Standard Oil of Indiana built the Yorktown refinery in 1956, and the company was renamed AMOCO in 1985. The refinery has been known locally as the "AMOCO refinery," even after AMOCO merged with British Petroleum in 1998, then Giant Industries purchased the refinery from BP in 2002, and Western Refining purchased Giant in 2007. In September, 2010, Western Refining closed the Yorktown refinery, but kept the oil storage and shipping facilities in operation.

In December, 2011, Western Refining announced the sale of the refinery, which had recently been connected to the Colonial Pipeline. The new owner, Plains All American Pipeline, disassembled and sold the idle refinery equipment. The refinery was converted into a terminal for storage/distribution of natural gas, biodiesel, crude oil, and refined petroleum products transported by ship, rail, truck, and pipeline.3

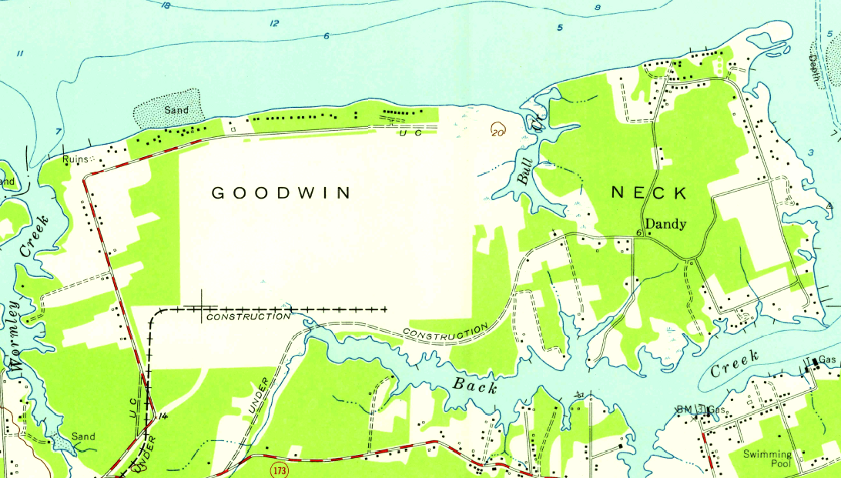

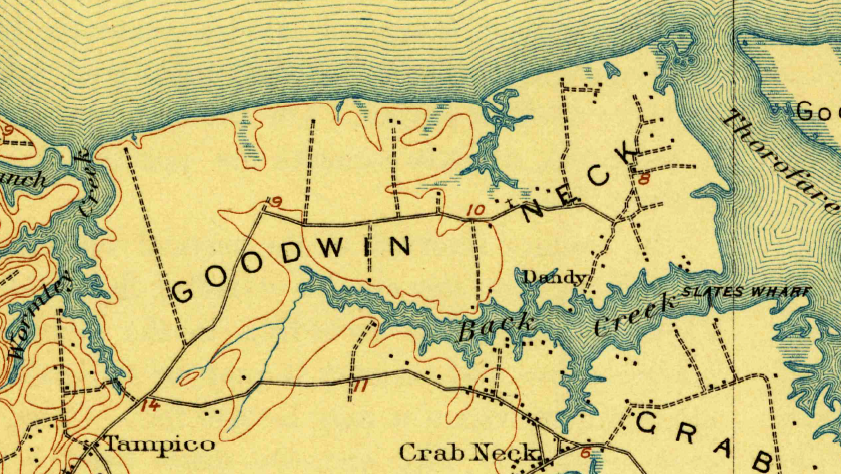

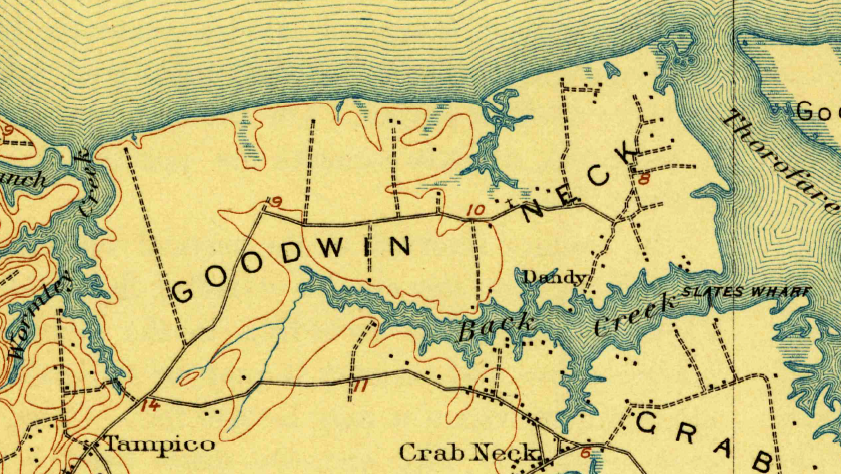

site of future oil refinery on Goodwin Neck at Yorktown, 1955

Source: US Geological Survey, Poquoson West 7.5x7.5 topographic map (1955)

site of future oil refinery on Goodwin Neck at Yorktown, 1955

Source: US Geological Survey, Hampton 15x15 topographic map (1907)

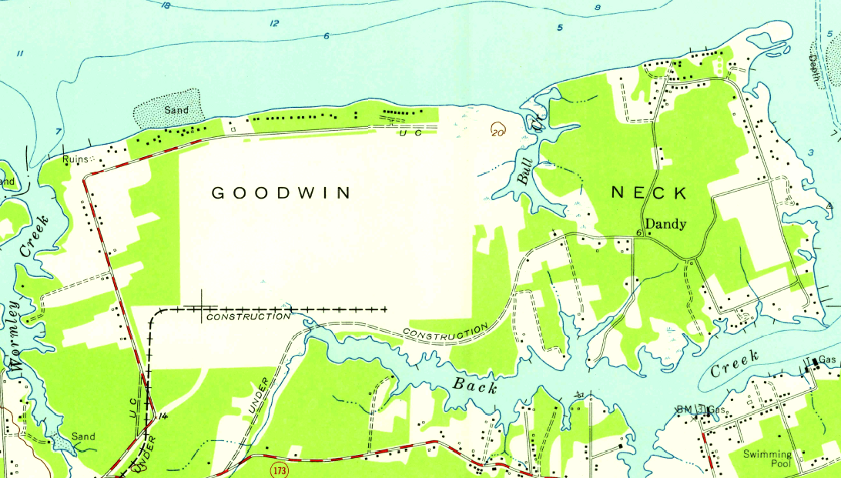

oil refinery on Goodwin Neck at Yorktown, 2010

(Yorktown Power Station is in upper left, south of Waterview Road)

Source: US Geological Survey, Poquoson West 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2010)

When in operation, crude oil was shipped to the refinery from a wide variety of foreign sources including Canada, the North Sea, West Africa, South America and the Far East.4

The refinery relied upon foreign oil arriving by tankers/barges; no pipeline connected it to the crude oil in Texas/Louisiana, and shipments of US-produced crude from the Gulf of Mexico oil fields would have increased transportation expenses. The Jones Act requires use of US-flagged vessels for interstate shipments between American ports - and such vessels have substantially higher operating costs than tankers registered in foreign nations.

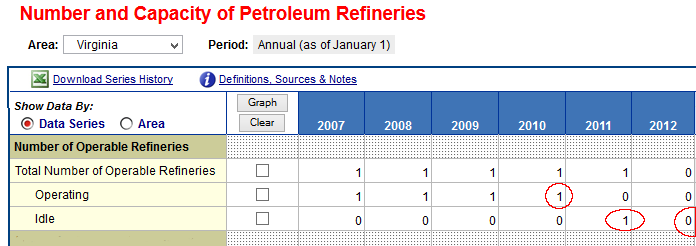

from one to none - Virginia's only operating refinery in 2010 was idle in 2011, and dropped completely from the statistics in 2012

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Petroleum and Other Liquids - Virginia

At the time of closure, the Yorktown facility was paying more property taxes than any other property in York County. Converting the refinery into a storage hub for petroleum and biodiesel products lowered York County tax revenue from the site from $4 million/year to $1.3 million/year, and eliminated about 200 jobs.5

The AMOCO refinery at Yorktown was also the first site in Virginia where industrial re-use was permitted for treated wastewater. The refinery's closure eliminated the prime customer for the effluent from the York River Treatment Plant of the Hampton Roads Sanitation District. The refinery was buying water treated to meet industrial standards for cooling equipment, at half the cost of water treated to meet standards for drinking. The sanitation district did not make a profit on the water sales, but did eliminate a portion of its nitrogen/phosphorous discharge into the Chesapeake Bay watershed.6

Shutting down the Yorktown refinery in 2010 matched business decisions by Sunoco, ConocoPhillips, and Hess in 2011 to close refineries in the Philadelphia area and one in the Virgin Islands. The refineries, like the one at Yorktown, were dependent upon foreign oil imported by tankers. There are no pipelines carrying crude oil from Texas/Louisiana to East Coast refineries on the Delaware River, and very limited pipeline capacity to ship crude from Canada/North Dakota to the East Coast. (The controversial expansion of the Keystone XL pipeline was designed to transport crude from Canada to Illinois/Texas refineries, not to the East Coast refineries.)

Refineries on the East Coast have depended upon low-sulfur ("sweet") foreign oil, often with a relatively high percentage of hydrocarbon molecules that had a low molecular weight ("light" crude). The East Coast and Virgin Islands refineries could not access lower-cost North American crude oil without paying a hefty premium for shipping in US-flagged vessels. That was not economical, especially as demand for gasoline and other refined products began dropping in the 21st Century due to fuel-efficient cars and a major economic recession in 2008-13.

Refinery closures in the US began after the Federal government abandoned its crude oil allocation and price control system in 1981. At one point in 2011, the price for refinery-produced gasoline was lower than the cost of raw crude oil imported from Nigeria. The economic value of refineries on the East Coast was limited and upgrades were not cost-effective when there was little or no profit margin. Rather than maintain the refining operations, Yorktown closed - at the same time other companies considered shutting down 50% of total East Coast refining capacity. As described by Financial Times:7

- US petrol demand has fallen steadily since 2007 as cars became more fuel-efficient, fuel marketers blended more corn-based ethanol into their product and high unemployment kept highway travel light. This wedged refineries between high input costs and a poor appetite for their fuel.

former oil refinery at Yorktown

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

The Yorktown refinery was disassembled and began to serve just as a storage/redistribution facility, but other East Coast refineries survived the 2008-2011 recession intact. Some were upgraded to process lower-cost North American crude, delivered by railroad tanker cars or new pipelines with liquids produced from "fracked" wells near the Ohio River.

Location and capacity of crude oil pipelines has been a significant factor in determining what refineries to maintain or close on the East Coast. Yorktown was dependent upon delivery of crude oil and upon export of refined products via tankers. Other refineries on the Delaware River had better access to pipelines and to railroads that could deliver crude in tanker cars, comparable to a pipeline.

The Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania refinery was reopened due to its ability to refine lower-cost liquids produced from Marcellus Shale natural gas wells, replacing some of the expensive light crude imports from the North Sea. The Marcellus Shale liquids moved from western Pennsylvania to Marcus Hook, after flow was reversed in an old pipeline which once carried refined products away from the refinery to markets in western Pennsylvania. Yorktown did not have such an option.8

Another large refinery in Delaware City, Delaware was partially reopened in 2011 after a two-year closure. That facility had the rare (on the East Coast) infrastructure to process "heavy" crude oil. The Delaware City facility began to refine crude oil from North Dakota and western Canada, shipped in by railroad tanker cars. While shipping by rail (and perhaps in part via barge down the Hudson River) can cost an extra $22/barrel compared to transport in a pipeline, the cost of the North American crude was expected to stay more than $22/barrel cheaper than European oil.9

The price of Canadian "sour" oil (with a high percentage of sulfur) produced from tar sands, and Bakken "sweet" (low-sulfur) crude extracted from the Williston Basin in North Dakota, is depressed because it is landlocked. There is limited pipeline capacity to distribute it to refineries, so the limited demand reduced the value of that oil. In 2012, Western Canadian Heavy crude was $37/barrel cheaper than European (Brent benchmark) crude, and $20/barrel cheaper than U.S. crude (West Texas Intermediate benchmark), while the Bakken crude oil was $17/barrel cheaper. Shipping that crude by rail to Delaware City is expensive, but still cost-effective.10

Though Yorktown lacked a pipeline to deliver relatively low-cost crude from fracked wells, the terminal was upgraded to receive various petroleum products by train. Crude oil from the Bakken formation in North Dakota is shipped via the CSX rail lines to Yorktown, in addition to already-refined products (ethanol and biodiesel). Those items are stored at Yorktown, then re-shipped via barge to various refineries and other terminals on the East Coast. The storage and distribution hub at Yorktown will have the capacity to receive two unit trains, with 80-100 tanker cars/train, carrying 130,000 barrels per day.

The oil trains increased CSX traffic on the railroad line bisecting the Peninsula. As an offset, the coal train traffic was reduced. Dominion Power retired the two coal-fired units at the Yorktown Power Plant adjacent to the old refinery site in 2015, converting one to natural gas supplied via a gas pipeline.11

The terminal was also upgraded to receive refined petroleum products (as opposed to crude oil) via pipeline. The Colonial Pipeline was already supplying the US Navy's nearby Yorktown Fuel Terminal. In 2011, Western Refining built a 24,000 barrels/day, one-mile pipeline connection to the old Yorktown refinery site. With the upgrades in rail and pipeline connections, the Yorktown terminal could obtain refined products for storage/distribution via pipeline, train, truck, and barge.12

the former oil refinery at Yorktown has been converted into an oil storage facility

Source: Google Maps

Unlike the "saved" and restarted Delaware and Pennsylvania refineries, the Yorktown facility will never again process crude oil into higher-value products. However, the environmental impacts of the petrochemical activity remain.

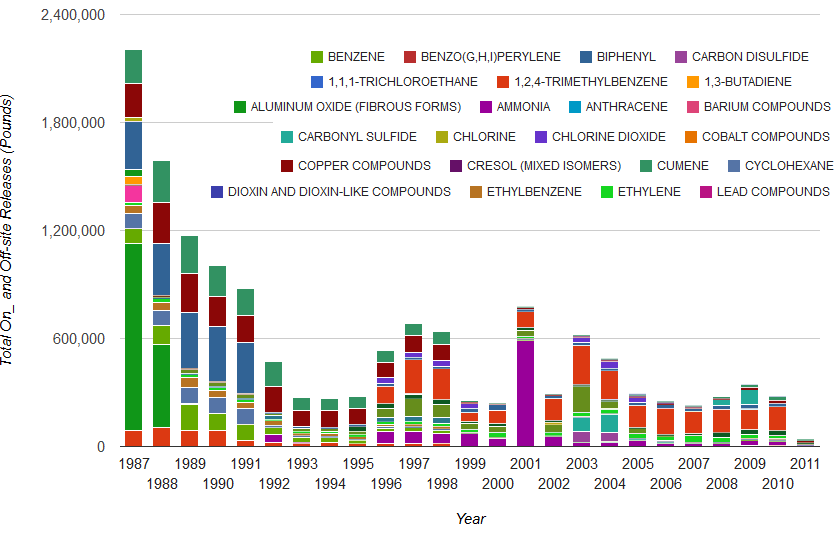

Two "landfarms" at the site were contaminated when petroleum sludge was dumped as waste, affecting groundwater in the Columbia Aquifer and the upper portion of the Yorktown Confining System aquifer. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified petroleum hydrocarbons such as benzene, toluene and xylene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenols, and heavy metals such as arsenic, chromium, and cadmium. A Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) corrective action plan was completed to monitor groundwater contamination exceeding Maximum Contaminant Levels of 15 contaminants.

According to EPA's RCRA Facility Investigation (RFI):13

- - groundwater contaminant plumes detected at concentrations higher than risk-based screening criteria appear to be confined to the site

- - A complete pathway may exist for potential recreational users (hunters, fishermen) in the areas of the York River, Bull Creek Pond, and the Tidal Marsh and Transition zones at the eastern edge of the Facility, however risk estimates calculated using RFI data show no unacceptable exposures are occurring.

- - groundwater impacts identified beneath the refinery are not migrating offsite in either the shallow or deep aquifer

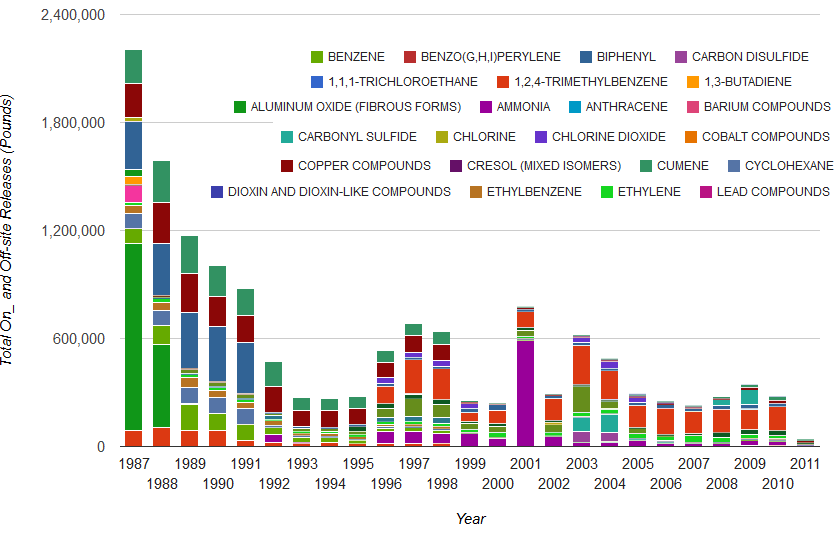

On- and Off-site Releases of toxic chemicals at Yorktown oil refinery

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Toxic Release Inventory Explorer

Links

- A Barrel Full

- Conserv

- Congressional Research Service

- Digital Commons

- Environmental Protection Agency EPA)

- Newport News Daily Press

- Reco Biodiesel (City of Richmond)

- Red Birch Energy (Bassett, in Henry County)

- Shenandoah Agricultural Products (Clearbrook, in Frederick County)

- Synergy Biofuels (Pennington Gap, in Lee County)

- US Department of Energy

- US Energy Information Administration

- Valley 25x'25 (helping Shenandoah Valley to achieve 25% renewable energy before the year 2025)

- Valley Proteins

- Virginia BioDiesel (West Point, in King William County)

- Virginia Tech - Center for Coal and Energy Research

- Virginia Department of Environmental quality

- Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy

- We Are The Practitioners

References

1. "US Number of Operable Refineries as of January 1," US Energy Information Administration, June 22, 2012, http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=8_NA_8O0_NUS_C&f=A; "East Coast (PADD 1) Number of Operable Refineries as of January 1," US Energy Information Administration, June 22, 2012, http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=8_NA_8O0_R10_C&f=A; "Number and Capacity of Petroleum Refineries," US Energy Information Administration, https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pnp_cap1_dcu_R10_a.htm; "After the shutdown, what comes next for the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery?," Penn Today, January 26, 2022, https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/after-shutdown-what-comes-next-former-philadelphia-energy-solutions-refinery; "Why gas is so expensive in some U.S. states but not others," Washington Post, June 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/06/20/gas-prices-by-state-explained/ (last checked June 21, 2022)

2. "Table 13. Refineries Permanently Shutdown By PAD District Between January 1, 1990 and January 1, 2012," Energy Information Administration, Refinery Capacity 2012, US Energy Information Administration, http://www.eia.gov/petroleum/refinerycapacity/table13.pdf (last checked December 24, 2012)

3. "Western Refining selling Yorktown refinery," Newport News Daily Press, December 1, 2011, http://www.dailypress.com/news/york-county/dp-nws-york-refinery-sale-1201-20111201,0,834647.story (last checked December 2, 2011)

4. "Western Refining to Shut Down Virginia Plant After Profit Margins Narrow," Bloomberg reports, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-08-05/western-to-shut-yorktown-virginia-oil-refinery-because-of-poor-margins.html (last checked December 23, 2012)

5. "Virginia's only oil refinery becoming storage facility," The Virginian-Pilot, December 23, 2012, http://hamptonroads.com/node/663129; "Western Refining suspending most operations at Yorktown plant," 13NEWS/WVEC.com television, http://www.wvec.com/news/local/Western-Refining-to-close-Yorktown-plant-100030339.html (last checked December 23, 2012)

6. "Water Reuse: Ensuring Wastewater Is Not Wasted Water," Hampton Roads Sanitation District, http://www.hrsd.com/firstreuseproject.htm (last checked December 23, 2012)

7. "Potential Impacts of Reductions in Refinery Activity on Northeast Petroleum Product Markets," U.S. Energy Information Administration, February 2012 (updated May 11, 2012), http://www.eia.gov/analysis/petroleum/nerefining/update/pdf/neprodmkts.pdf; "Energy: Refined out of existence," Financial Times, April 9, 2012, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/256f583c-7a83-11e1-8ae6-00144feab49a.html (last checked December 24, 2012)

8. "Former Sunoco refinery in Marcus Hook will process Marcellus Shale products," Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 2012, http://articles.philly.com/2012-09-28/business/34128480_1_ethane-sunoco-logistics-sunoco-s-marcus-hook (last checked December 23, 2012)

9. "PBF Energy bets big on crude-by-rail to feed ECoast ref," Trainorders.com, November 26, 2012, http://www.trainorders.com/discussion/read.php?2,2927408,nodelay=1; "Rail it on over to Albany - Moving Bakken East," RBN Energy LLC, May 14, 2012, http://www.rbnenergy.com/Rail-it-on-over-to-Albany-Moving-Bakken-East (last checked December 23, 2012)

10. "PBF to run more Bakken crude at Delaware City," Reuters, August 24, 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/08/24/us-refinery-operations-pbf-delcity-idUSBRE87N0UA20120824 (last checked December 25, 2012)

11. "New details reveal scope of expansion at former Yorktown refinery," Newport News Daily News, August 6, 2012, http://articles.dailypress.com/2012-08-06/news/dp-nws-york-yorktown-terminal-announcement-0807-20120806_1_yorktown-refinery-rail-plains; "Rail it on over to Albany - Moving Bakken East," RBN Energy LLC, May 14, 2012, http://www.rbnenergy.com/Rail-it-on-over-to-Albany-Moving-Bakken-East; "Integrated Resource Planning," Dominion Resources, https://www.dom.com/about/integrated-resource-planning.jsp (last checked December 25, 2012)

12. "Colonial Announces Expansion Of Virginia Line," Colonial Pipeline, October 31, 2011, http://www.colpipe.com/press_release/pr_111.asp (last checked December 25, 2012)

13. "Documentation Of Environmental Indicator Determination" for BP Yorktown Refinery, Environmental Protection Agency, February 5, 1999, http://www.epa.gov/reg3wcmd/ca/va/hhpdf/hh_vad050990357.pdf (last checked December 25, 2012)

Rocks and Ridges - The Geology of Virginia

Energy

Virginia Places