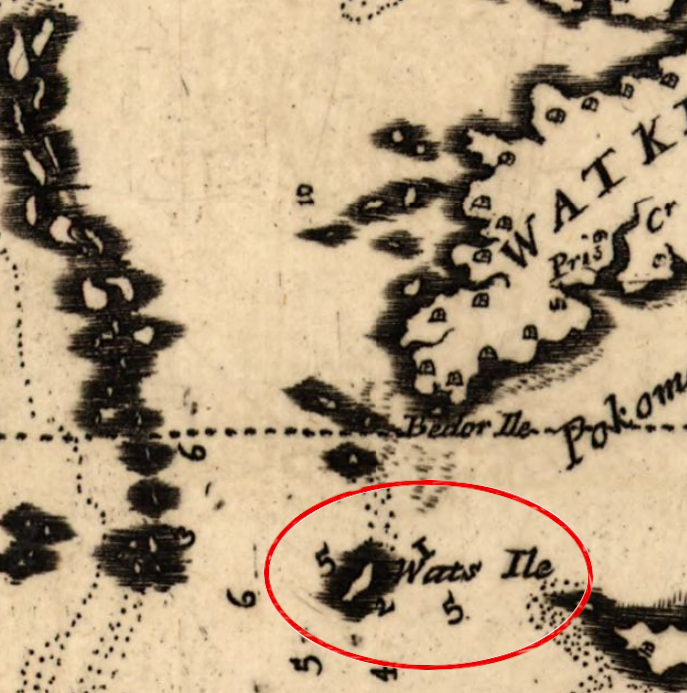

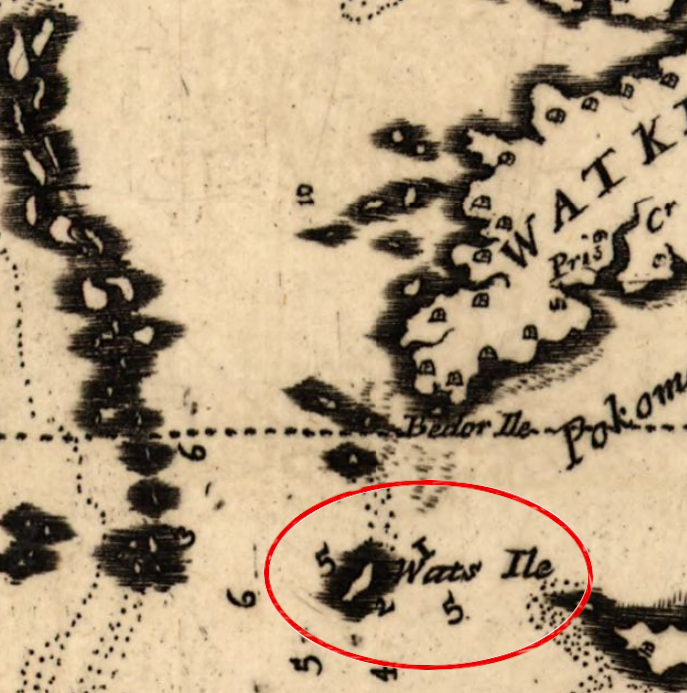

Watts Island got its current name in 1670

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

Watts Island got its current name in 1670

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

Watts Island is one of the islands that has been abandoned. It was patented Nickolas Waddelow in 1652, and he called it St. Gabriell's Island. He sold a portion to John Watts, and mapmaker Augustine Herrman named the island after him in 1670.

In 1685, Rodger Makeele used the island as a base for piracy. He organized several men and started by seizing a small boat loaded with 20,000 pounds of tobacco. It's three-man crew had stopped for the night at Watts Island, and were unarmed when the pirates appeared out of the dark. For about two months, Makeele and his men used several Chesapeake Bay islands as a base from which they sailed out to capture shipping, raid shoreline plantations, and even steal guns and furs from Native American groups on the Eastern Shore. When the threat of capture became to great, he abandoned the Chesapeake Bay and established a new base in North Carolina.

It was used as a base by Loyalists during the American Revolution. Ships could sail from there to plunder shoreline plantations, and even seize other ships sailing on the Chesapeake Bay. The British built a fort on Watts Island during the War of 1812, though Tangier Island was their major base.

In 1800, 15 people lived on Watts Island and raised cattle there on the marsh grasses. In 1833, the US Government purchased Little Watts Island and built a lighthouse, placing the light fueled by kerosene at the top of a 48-foot tall tower. During the Civil War, both Union and Confederate sailors cut all the trees for firewood to fuel the boilers of steamships, but the seven-acre island stayed under the control of Union forces due to their more-powerful Navy presence.

In 1877, arbitrators defined the boundary between Maryland and Virginia in the Chesapeake Bay. Their zig-zag line placed Watts Island, along with most of the oyster-rich Pocomoke and Tangier Sounds, clearly within Virginia.1

Steady erosion reduced the size of Watts Island. In 1908 a storm cut it in half, and the last residents left. Two years later, a New Jersey lawyer moved to Watts Island after his brother purchased it. Charles Hardenberg 's intention was to restore his mental health by reducing stress. Companionship on the island was limited, with just annual trips to the Eastern Shore to get supplies. In 1915, the lighthouse keeper transferred to New Point Comfort and Charles Hardenberg took the job at Little Watts Island. When the light was automated in 1923, he moved back to Watts Island.

A 1930 interview with a New York newspaper made him famous briefly as the "hermit" in the Chesapeake Bay. He traveled to New York, quickly found a wife, and then the pair went to live on Watts Island. The 1933 hurricane forced them to flee to the Eastern Shore. Mrs. Hardenberg chose to stay there, while her husband returned alone. He left Watts Island three years later due to illness, and died at his brothers home in 1937.2

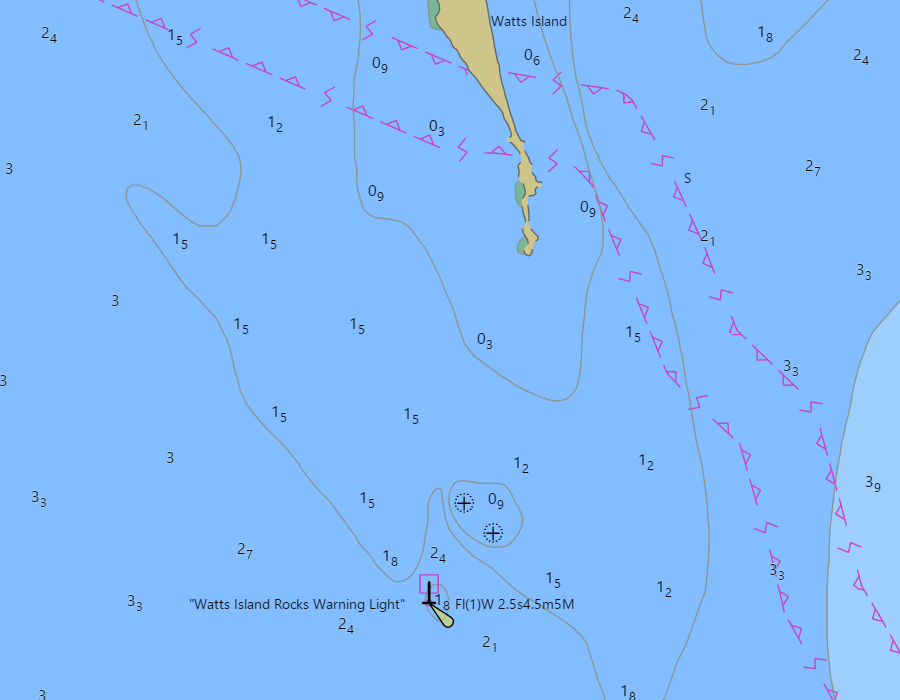

By 1923, erosion had washed away over 50% of Little Watts Island. In 1944, the lighthouse tower collapsed after a severe storm. Bricks not salvaged for use in buildings on the Eastern Shore now form underwater "structure" which attracts fish. Today, Little Watts Island is just a shoal with Watts Island Rocks Warning Light on a tower.3

Little Watts Island is now a navigation hazard with a warning light

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NOAA ENC Viewer

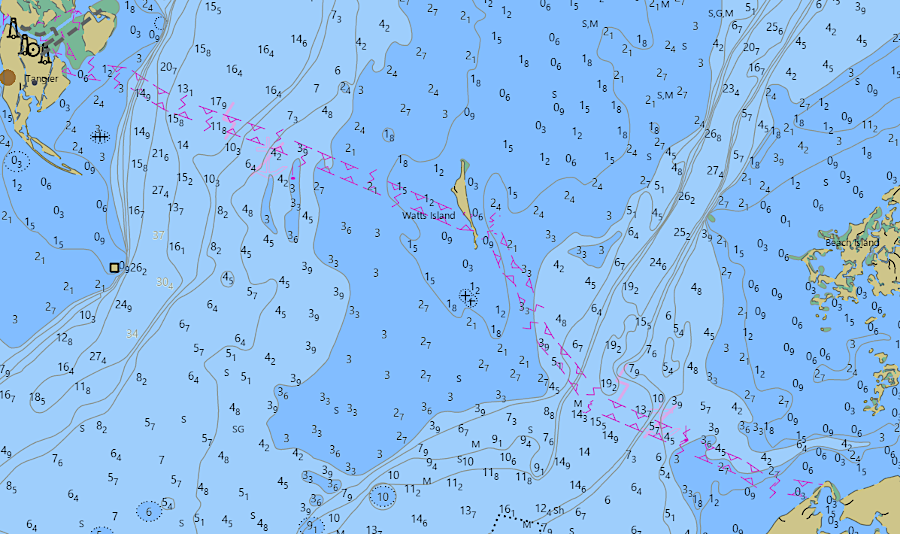

In 1977, a submerged cable was installed between Onancock and Tangier Island to provide reliable electricity, replacing diesel generators on Tangier. The cable crossed Watts Island and a junction box was erected on the upland. Today, a tower has been erected to support the junction box because so much of the land has eroded beneath it.4

nautical charts mark the route of a submerged electrical cable which crosses Watts Island

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Electronic Navigational Charts (ENC) Viewer

G. R. Klinefelter, who owned a house at Tangier Island, purchased Watts Island at auction in the 1960's. He used dredge spoils to protect his house on Tangier from erosion, but allowed the natural process to continued on Watts Island. As the cemetery there was washing away, Klinefelter rescued a few headstones and moved them to Tangier. Klinefelter allowed the Chesapeake Bay Foundation to use Watts Island for educational field trips until selling it in the early 1990's.5

The Conservation Fund purchased Watts Island, then donated it in 1995 to the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Watts Island is now included within Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, part of the Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Its least tern nesting colony is one of the largest colonial bird rookeries in Virginia.

Bald eagles nest in the loblolly pines still growing on the 125-acre island. Refuge staff erected peregrine falcon hacking towers there, and successfully reintroduced falcons to restore the population.6

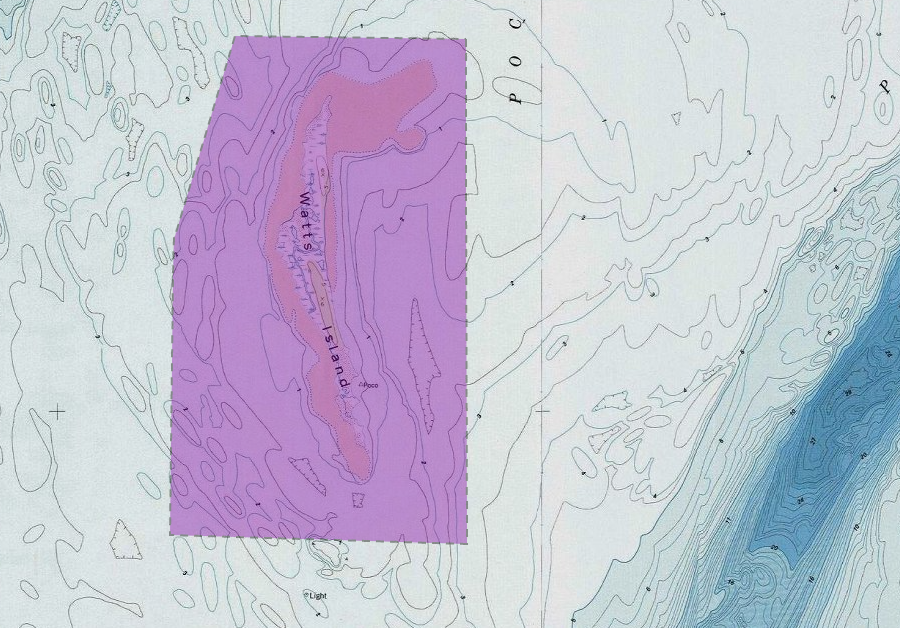

Watts Island is included within Unit VA-27 of the Coastal Barrier Resources System. The US Fish and Wildlife Service calculates that the island has 13 acres of upland, and the entire unit includes an additional 1,972 acres of wetlands, marshes, estuaries, inlets, and open water landward of the coastal barrier.7

the 13 acres of "fastland" and an additional 1,972 acres of aquatic habitat at Watts Island are included within the Coastal Barrier Resources System

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, CBRS Projects Mapper

Watts Island is now part of the Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tangier Island VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)