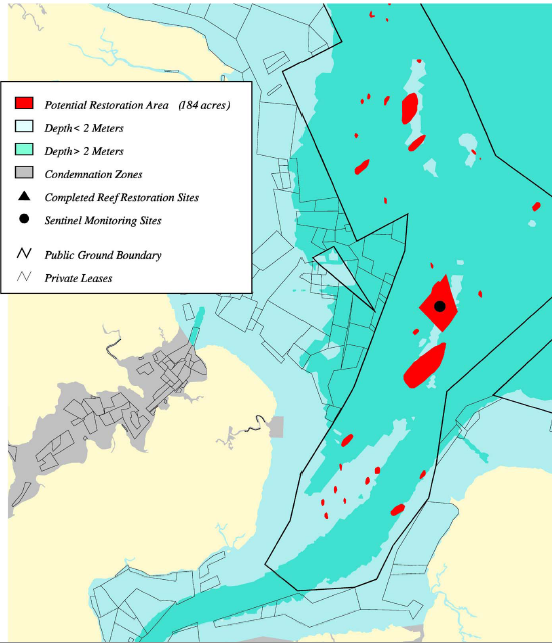

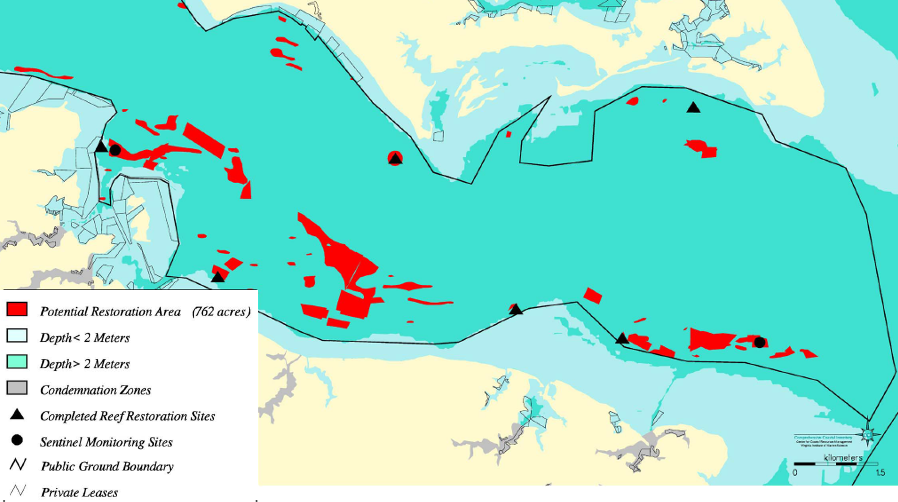

oyster restoration site, confluence of Nansemond and James rivers

Source: Virginia Oyster Reef Restoration Map Atlas

oyster restoration site, confluence of Nansemond and James rivers

Source: Virginia Oyster Reef Restoration Map Atlas

Oyster restoration began on a large scale in Virginia at the start of the 20th Century, by private individuals who had an economic interest in growing oysters for profit.

In 1892-94, the Baylor Surveys in Virginia delineated areas where oysters were growing naturally and identified submerged lands that were barren of oysters. (Maryland defined its Natural Oyster Bars in surveys by C.C. Yates between 1906-1912.) In Virginia, these barren areas were made available for lease (privatized) at very low cost per acre.

Private aquaculture used the same techniques as the state used on public oyster grounds. However, the right to harvest the oysters that grew on "private rocks" (submerged land leased by the Commonwealth of Virginia) was limited to the leaseholder.

Leaseholders bought old oyster shells from packing houses or dredged them from fossil oyster reefs in the James River. The shells were shipped to privately-leased submerged tracts, then stocked with young seed oysters that were often harvested from the living reefs on the James River.

After a year or two, the seed oysters grew to market size and were harvested by the leaseholder - assuming an unauthorized oyster pirate had not scraped up those oysters illegally. The Ballard Fish & Oyster Company on the Eastern Shore still advertises that is has been "producing great shellfish since 1895."1

The state used public funding to restore natural, still-producing oyster bars within the areas delineated in the Baylor Surveys. Oyster shells were dumped on the natural oyster bars, not the barren submerged lands identified in the Baylor Surveys and then leased for private aquaculture initiatives. The "public rocks" were available for public harvest by watermen who could not afford to pay for private leases and develop "private rocks."

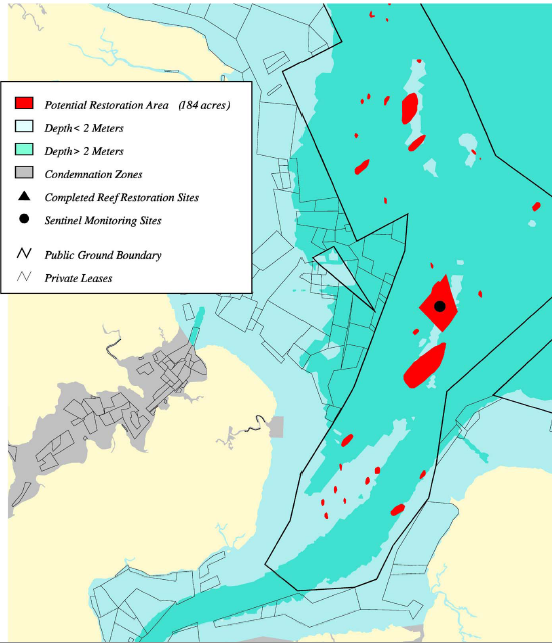

the Baylor Surveys defined the boundaries of public oyster grounds in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Norfolk: Public Oyster Grounds (1892)

Expanding the square footage of hard substrate created more suitable oyster habitat on the river bottom. More oysters grew, but the state did not impose tight restrictions on harvest. Tonguing and dredging dispersed the shells on the public rocks, reducing three-dimensional reefs into scattered piles. That limited natural oyster reproduction. Restoration on public rocks became a put-and-take fishery, comparable to annual stocking of trout in mountain streams for recreational fishing.

oyster shell with spat, suitable for transplanting as a seed oyster

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery: Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan - Maryland and Virginia

The state investment in oyster restoration on public rocks was justified in part because it created economic opportunities for the watermen and the influential oyster shucking houses. The public paid for increasing the oyster supply, though only few private individuals quickly harvested the benefits. The oyster restoration process was a subsidy for a traditional industry. The put-and-take restoration approach was not a cost-effective was to increase the oyster population,, but it was politically popular in the thinly-populated counties along the Chesapeake Bay.

Because the new oysters were quickly harvested, restoration efforts failed to increase the overall population of oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. Few people considered re-establishing oyster bars without harvesting the oysters, just to provide filter-feeders that could help to re-balance the ecology of the Chesapeake Bay.

The political and economic reasons for authorizing harvest of restored sites was joined by a biological reason, starting in the 1950's. The single-celled protozoan parasite known as Dermo (Perkinsus marinus) was first identified in the Chesapeake Bay in 1949. A decade later, the parasite MSX (Haplosporidium nelsoni) infected oysters where salinity was at least 15 parts per thousand (15ppt).

Both diseases killed oysters before they reached marketable size, but oyster beds in the Rappahannock River survived better. The spring runoff of freshwater in that river reduced salinity below the thresholds acceptable to the Dermo and MSX parasite in April/May, at a time when water temperature exceeded 15°C. In other streams, the timing of the salinity drop occurred when the water temperature was lower and the parasites were still dormant, or after the water temperature had climbed to the point where diseases had already damaged the oyster population.2

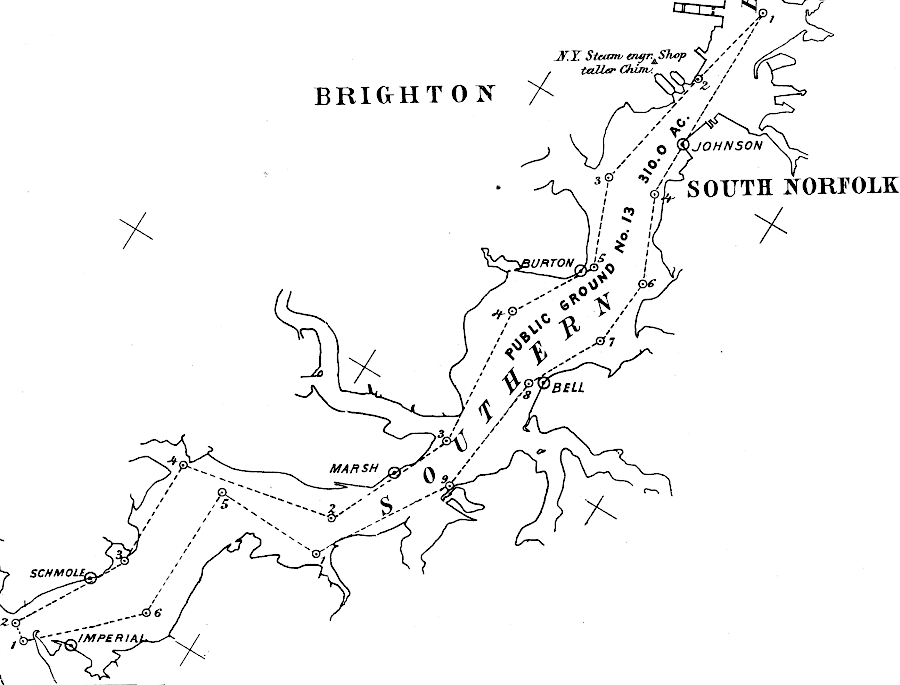

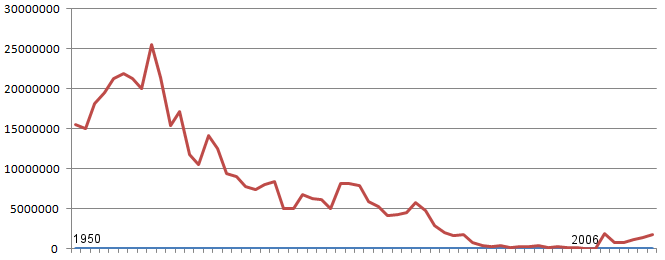

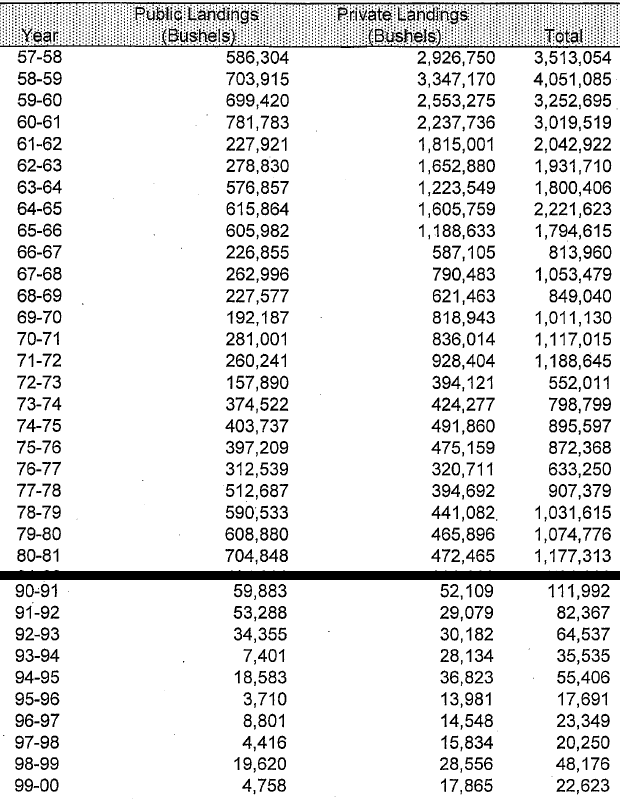

oyster harvest, measured by bushels, shows a dramatic decline between 1958-1994

Source: Oyster restoration efforts in Virginia, Oyster Ground Production (p.118)

oyster harvest (shown here in pounds rather than bushels) has begun to recover since 2006

Source: National Marine Fisheries Service, Annual Commercial Landing Statistics, 1950-2012

Since most oysters were dying within the first three years of their life, the restocked beds would be "wasted" if not harvested quickly. However, any oysters with potential to survive sediment, predation by cow-nosed rays, and disease were removed by quick harvest. As a result, restocked oyster beds never had a chance to regrow to their previous extent (and the opportunity for oysters to evolve resistance to the diseases was lost with each harvest).

Commercial harvest dropped from 4 million-7 million bushels/year in 1880-1925 to a low point of just 18,000 bushels in 1995-96. That triggered a change in oyster restoration policy.3

To increase the oyster population, Virginia and its partners in the Chesapeake Bay Program adopted the new strategy of creating oyster sanctuaries, where harvest was 100% prohibited. There are ecological reasons for oyster restoration separate from the economic objectives to increase the commercial harvest.

More filter-feeding oysters (each one processing 3-12.5 gallons of water daily) could improve the water quality in the Chesapeake Bay. Oysters had the potential of stripping some excess nutrients from the water column. By one calculation, harvesting 100,000 oysters will remove six pounds of nitrogen and phosphorus from the Chesapeake Bay.

The oyster restoration project manager for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation commented:4

Adding more oysters into the waters of the Chesapeake Bay could help Virginia come closer to meeting the Clean Water Act requirements. If the oysters were protected by sanctuaries, they could help "Save the Bay." If the oysters were harvested and enjoyed by consumers who do not live close to the water, the oysters might stimulate public support for public policies and investments that have even greater impact on pollution that filtering the water.

The Chesapeake Bay Agreement signed in 2000 included a specific goal for using protected areas as a technique for restoring oysters:5

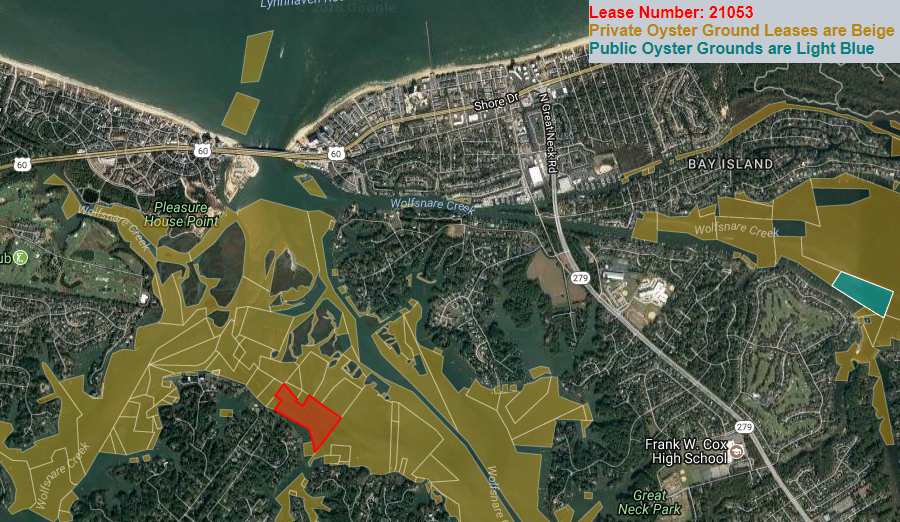

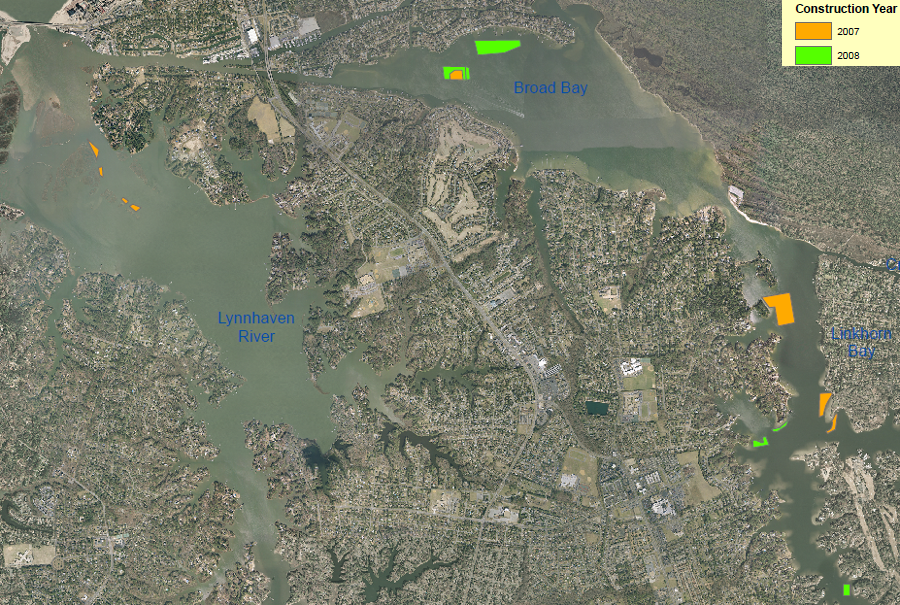

Virginia Beach has acquired its own oyster leases on the Lynnhaven River and Broad Bay to support restoration projects.

Virginia Beach acquired Lease #21053 for oyster restoration in the Lynnhaven River

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Maps: Oyster Ground Lease

Since the 1800's, the standard process for growing oysters in the bay has been to scatter oyster shells on the bottom and wait to see if the site produced mature oysters in two-three years. In 1993, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (in cooperation with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science) began to build three-dimensional vertical reefs, rather than just spreading a thin layer of shells on the bottom.

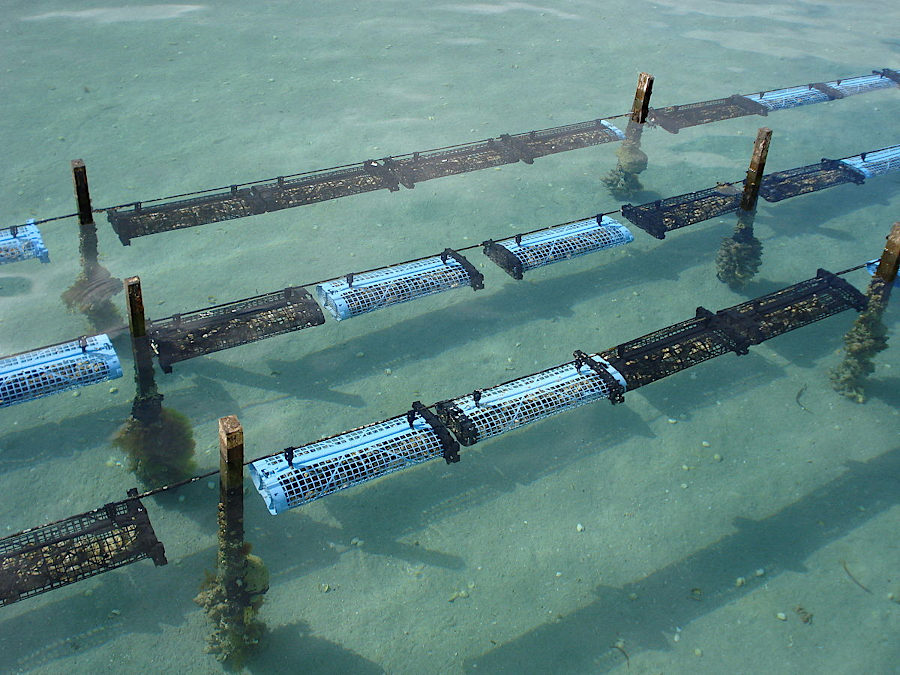

aquaculture - growing oysters in floats, Taskinas Creek

(Chesapeake Bay Virginia National Estuarine Research Reserve)

Source: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

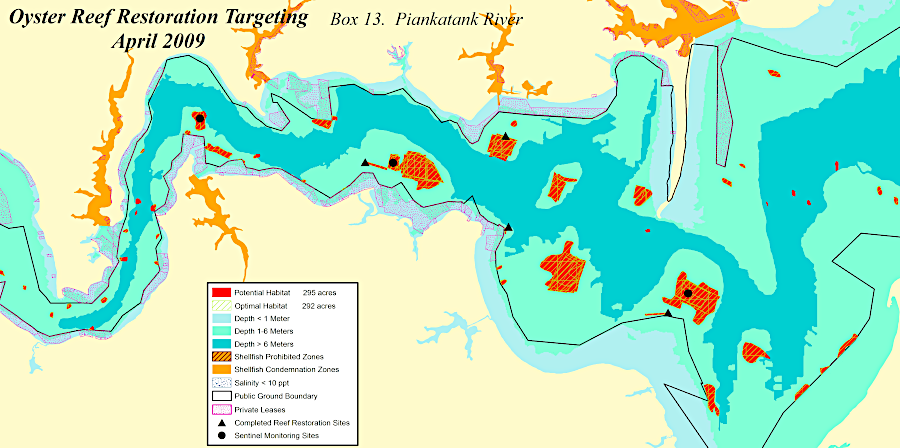

The reefs were created in new sanctuaries established at the mouth of the Piankatank River. Since 1963 the site had been managed for producing seed oysters, which were harvested soon after larvae "set" and then moved to other locations where the oysters grew into maturity.

granite rock, brought in by barge, was methodically placed in the Piankatank River near Gwynn's Island in Mathews County

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

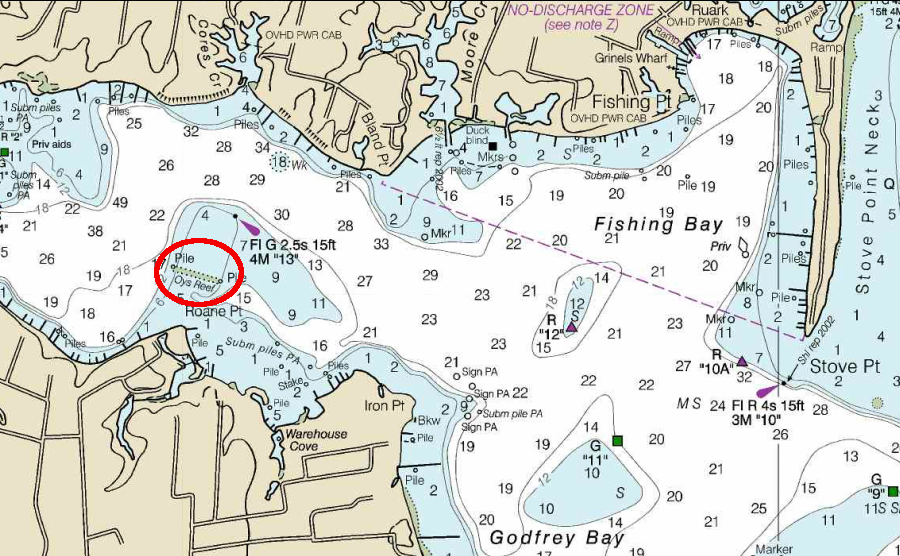

The Piankatank River was a good location for generating seed oysters because, within the embayment at the river mouth, brackish water flowed in a gyre. That pattern trapped oyster larvae and created high potential for larvae to settle onto a hard surface and create a productive reef. In addition, water quality was good since there was so little development upstream in the Piankatank River/Dragon Run watershed. The state created Palace Bar Reef and designated it as a sanctuary, banning harvest to ensure that dredging/tonguing would not alter the vertical structure by scraping off the top layer.6

moving granite from barge to the bottom of the Piankatank River, to provide oysters a base for building a new reef

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

Additional artificial reefs have been created in that bay and elsewhere. In the 20 years after the Palace Bar Reef project, Virginia constructed more than 100 sanctuary reefs, investing in three-dimensional structures as well as spreading shell onto flat oyster beds.

In 2012, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation expanded Palace Bar Reef again, but used a different technique. It added hollow concrete spheres ("reef balls") already covered with spat, after sinking the balls in the Virginia Institute of Marine Science oyster hatchery tanks. Reef balls were used to create a three-dimensional substrate rather than natural shell, because the supply of oyster shell could not meet the demand for restoration. In 2014, The Nature Conservancy committed funding to create a new reef nearby in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, this time using recycled concrete.7

Palace Bar Reef, at the mouth of the Piankatank River, was the first three-dimensional reef for oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Rappahannock River, the state built 14 one-acre sanctuary reefs. Broodstock (mature oysters capable of spawning) was planted and then protected from disturbance. In additional, 500 acres of two-dimensional bars were constructed, scattering shells on the Rappahannock River bottom that would provide habitat for the larvae generated naturally on the different sanctuary reefs.

The presence of new reefs and bars with large oysters, grown to marketable size, led to political pressure to permit commercial harvest at those sanctuaries. The success of the restoration forced Virginia to find a middle ground between "let the watermen harvest everywhere" and "keep the oysters undisturbed forever."

Virginia implemented an oyster management solution that was intended to balance the ecological objectives of increasing oyster populations with economic opportunity. The 500-acre harvest area on the Rappahannock River was divided into six sections.

Two sections were opened for harvest every three years, allowing oysters to grow for two years undisturbed before a section was harvested on the third year. In addition, watermen were required to place the largest oysters on the sanctuary beds as broodstock, rather than selling them to customers. The rotating schedule enhanced spawning from the three-dimensional sanctuary reefs, but still provided annual opportunity for watermen to make a profit.8

Permanently-protected oyster sanctuaries now are providing broodstock for re-stocking public oyster beds, and other public oyster grounds are being harvested on a rotating basis. The schedule allows time for young oysters to grow, then be collected before the diseases of Dermo and MSX kill the mature oysters. The management scheme involves having enough beds in the harvest phase each year to keep watermen busy collecting large oysters, reducing the temptation to poach small oysters from closed areas. As described in a 2011 news release from the governor, celebrating the rebirth of the industry in Virginia:9

Rappahannock River Oyster Management Areas

Source: Virginia Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Program, Virginia Oyster Gardening Guide

Sanctuary reefs create masses of interconnected oysters, which are more capable of resisting predation by cow-nosed rays than the two-dimensional bars. In 2006, after scientists planted 750,000 oysters on a flat bar in the Piankatank River and even added a layer of shells to protect the new oysters, a school of cow-nosed rays ate 94% of them in just five days. In 2008, a planting of a million oysters in the York River was "vacuumed up" by rays.

One option considered by state officials was to create a market for eating cownose rays. The objective was to entice fishermen to catch the rays, so fewer rays would eat fewer oysters. It was an approach comparable to efforts on land to increase the number of preferred game animals such as deer/elk, by reducing the number of predators such as wolves/coyotes. Another major predator of oysters, the blue crab, has been managed through commercial harvesting for many decades.

The cownose rays were advertised as Chesapeake Rays, leading to one headline "Help the Bay, eat a Chesapeake ray." However, no population assessment was completed to determine if a cownose ray fishery would be sustainable, and a decade later new research revealed that they were not major predators of oysters:10

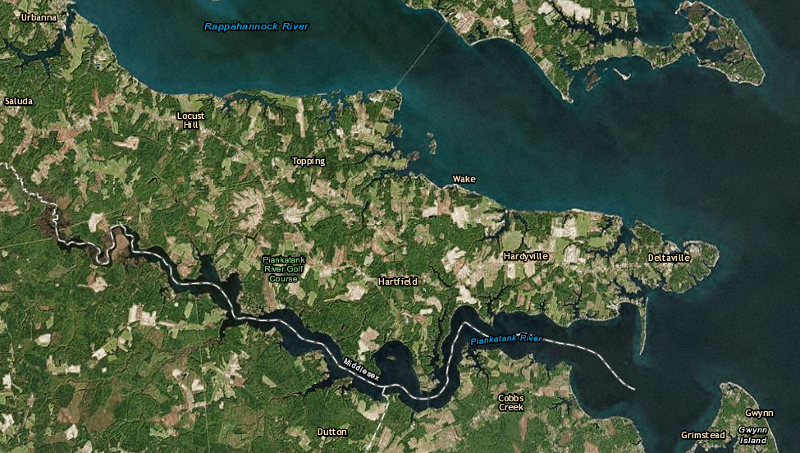

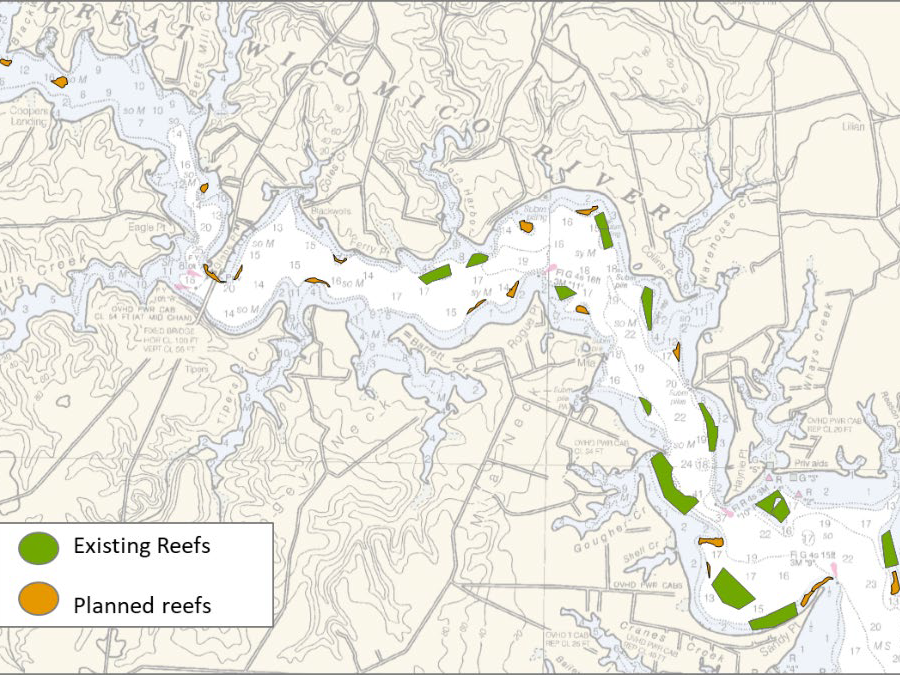

A five-year experiment at building new reefs in oyster sanctuaries on the Great Wicomico River showed that tall (10-18 inch) reefs were more successful in recruiting new oysters than short (3-5 inch) reefs. Tall reefs benefited from currents removing sediments and providing more algae for oysters to eat, and prohibiting harvest preserved the vertical structure.

In harvested areas, the natural reef is lowered by tonguing and dredging as oysters are scraped away. The areas open to harvest typically have 2-11 oysters/square meter, while the short reefs built in the Great Wicomico River sanctuary developed 250 oysters/m2 and the tall reefs had 1,000 oysters/m2. The Corps of Engineers defines restoration as "successful" if the live adult oyster density is at least 50/m2.

The restoration effort on the Great Wicomico River produced dramatic results, in part because water circulation patterns in that area tend to trap oyster larvae which then could set on the artificial reefs:11

less than 100 acres in an oyster sanctuary on Great Wicomico River has more oysters than all 270,000 acres of public oyster grounds in Maryland, demonstrating the productivity of vertical reefs undamaged by harvesting

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Oyster sanctuaries and public oyster grounds are being replenished with shells dredged from various sites. As sea level has risen since the end of the last Ice Age, "fossil" reefs are now located too deep underwater to sustain oysters. It is possible to dredge those shells and redistribute them to locations within the Chesapeake Bay where oysters could thrive, if they had suitable substrate for spat to start growing.

The primary source for shell has been old reefs on the James River that were once highly productive. Old reefs on the Piankatank River have also been dredged.

Dredging and redistribution has been controversial at times. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources was unable to get a permit from the state's Board of Public Works and the US Army Corps of Engineers to dredge shells from the Man o' War Shoal near the mouth of the Patapsco River. Recreational anglers feared the dredging would damage the habitat for finfish. The estimated 100 million bushels of oyster shells are still intact at Man o' War Shoal.

In 2021, the Potomac River Fisheries Commission used nautical maps to identify 30 sites within a 10-mile stretch of the Potomac River, upstream of the U.S. 301 bridge, which could be fossil oyster reefs with one million bushels of shell. At some time in the past, for perhaps decades or a century, the habitat was suitable for at least small oysters to grow.

Today the salinity level in that stretch is less than 10 parts per 1,000, too low for oysters. Hurricane Agnes brought so much fresh water and sediment downstream that nearly all oyster reefs upstream of the Route 301 bridge were wiped out. The last reef survived until heavy rain lowered salinity too low in 2019.

The Potomac River reefs were particularly attractive as a source of shell because there was little silt and mud on top; extracting buried shell deposits would not impact water quality as much as hydraulic dredging of other reefs. However, the fossil reefs are a non-renewable resource. They provide rare hard substrate which may be essential for sturgeon to breed successfully. Using the shells for oyster restoration could damage sturgeon restoration efforts.

The demand for shells exceeds the supply, so other material has been used to create artificial reefs. Ground concrete was scattered on the bottom of the Piankatank River to build the foundation for a new oyster reef there.

the Piankatank River oyster reef was started with ground-up concrete

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 140530-A-OI229-047

a Lafayette River oyster reef was built with fossilized oyster shell

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 140314-A-ON889-108

Restoration of public sites, and creation of new habitat on private leases, has helped increase the population of oysters in the bay. Watermen are harvesting increasing numbers of bushels from both "public rocks" in the winter, and from private leases on submerged river/bay bottom in the summer.

In 2012-13, the Virginia harvest increased to 400,000 bushels, then 500,000 bushels in 2013-14.

Private aquaculture based raising oysters in cages, a practice that has grown substantially since 2008, is playing a key role in re-establishing the oyster industry in Virginia. By 2018, Virginia had leased over 130,000 acres of bottom for raising oysters.12

Modern oyster gardening does not require the old techniques of harvesting with tongs and dredges on the open water during the October-February season (extended into April on the James River). Restoring the oyster through aquaculture benefits the ecology of the bay and economics of waterfront towns, but growing oysters in cages rather than on oyster beds will not preserve the traditional skills or tools of Virginia's remaining 1,000 watermen.13

bushels of oysters harvested from Virginia waters

Source: Governor of Virginia news release, Virginia's Oyster Harvests Boom (February 7, 2012)

(see entire chart)

Virginia, Maryland, and Federal officials have a common perspective on the science of oyster restoration, but differ on the politics and priorities.

For a century, Maryland focused on managing oyster beds that were open to public harvest, while Virginia enabled private leases for creation of new oyster beds on submerged land that was no longer naturally productive. Federal officials got involved in oyster recovery as part of efforts to reduce pollution and "Save the Bay" so it met the standards of the Clean Water Act.

Initial Federal efforts in Virginia mimicked the state's approach, with the addition of new shells to public oyster beds in the Rappahannock River in 2000 and in Tangier Sound in 2002-2003. However, the Federal efforts were intended to create ecological benefits rather than support traditional harvesting by watermen.

The Corps of Engineers concluded that the state's approach (known as "repletion") was not cost-effective, because harvesting removed the oysters and damaged the oyster beds as fast as they were restocked. The Corps estimated that 1/3 of the oysters placed in Maryland sanctuaries between 2008 and 2010 were harvested illegally by poachers. Federal agencies (in addition to the Corps, the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration funded oyster restoration projects) stopped trying to grow oysters at public expense and plant them for private harvest, which socialized the costs while privatizing the benefits:14

At the end of 2018, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission made it harder for Maryland to maintained its traditional repletion program. It stopped issuing permits to transfer seed oysters to Maryland. The state agency also ended the Fall 2018 harvest of seed oysters from the James River earlier than planned, to avoid exceeding the quota of 40,000 oyster seed bushels.

Since 2011, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission had authorized a Spring harvest of 80,000 bushels of seed oysters and a Fall harvest of 40,000 bushels. At least half of the James River seed oysters were sold to be placed on the bottom of rivers and the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland.

Maryland had no source of seed oysters for transplanting. Virginia officials assumed they had a surplus on the Piankatank and Great Wicomico rivers as well as on the James River.

Virginia scientists were concerned that too many seed oysters would be harvested. Virginia watermen were concerned because the transplanted oysters reduced the supply in Virginia and increased the supply from competitors in Maryland.15

allowing or blocking oyster harvest from sanctuary reefs is controversial in Maryland

Source: Chesapeake Network, WaterSavers cartoon

The conflict between state-Federal restoration priorities was revealed clearly in 2011, over repletion of reefs on the Great Wicomico River. The Corps and the state had cooperated on creating the state's largest artificial reef project since 2004. The sanctuary reefs were off-limits to commercial harvest, and in 2011 Virginia decided that it would not contribute its 25% share unless some acreage could be opened to watermen. Federal rules allowed restoration funding for just sanctuaries.

The ultimate compromise led to the Federal government spending only $600,000 of the planned $2.5 million for the Great Wicomico River that year. The sanctuary reefs in the Great Wicomico River were raised to a higher level by the addition of new shell, providing more habitat for oysters.16

the initial sanctuary reefs created in 2004 on the Great Wicomico River were raised by the addition of more shell

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

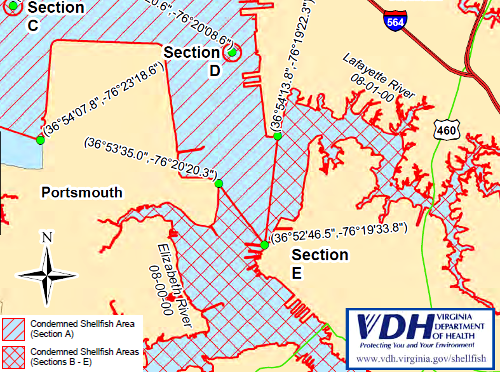

The state also rejected $200,000 for construction of new oyster reefs in the Lafayette River. The river has been closed to shellfish harvesting since 1934 due to bacterial pollution from Norfolk's sewage and stormwater runoff, so increasing the oyster population in the Lafayette River would provide no economic opportunity for commercial harvest.17

there is now an oyster sanctuary reef along the Elizabeth River shoreline next to the Corps of Engineers office building

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

The Lafayette River was the first target for restoration, with support from the Elizabeth River Project. The river suffered summertime red tides (algae blooms) triggered by excessive nutrients from nearby residences, but had high potential for recovery because there was little industrial development along the shoreline except for the Norfolk Naval Base at the river's mouth.

In 2010, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation placed the first reef balls used for oyster restoration in Virginia into the Lafayette River, after the reef balls were stocked with spat produced at the Virginia Oyster Restoration Center in Gloucester County next to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS). The state agency partnered with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and facilitated growing oysters for restoration.

Private hatcheries grew the oysters for restoration projects. The two Virginia Institute of Marine Science hatcheries, at Gloucester and the Kauffman Aquaculture Center on the Rappahannock River, focused on oyster-breeding to generate brood stock for oyster farmers. That was the aquaculture equivalent of the Virginia Department of Forestry growing seedlings at the state nurseries for sale to commercial tree farms.

In addition, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science conducted research on oysters. The Gloucester hatchery, which opened in 1975 without heating, could raise oysters only between March-June. A replacement facility opening in 2022 finally included adequate temperature controls for raising oysters for research and brood stock between January-September.18

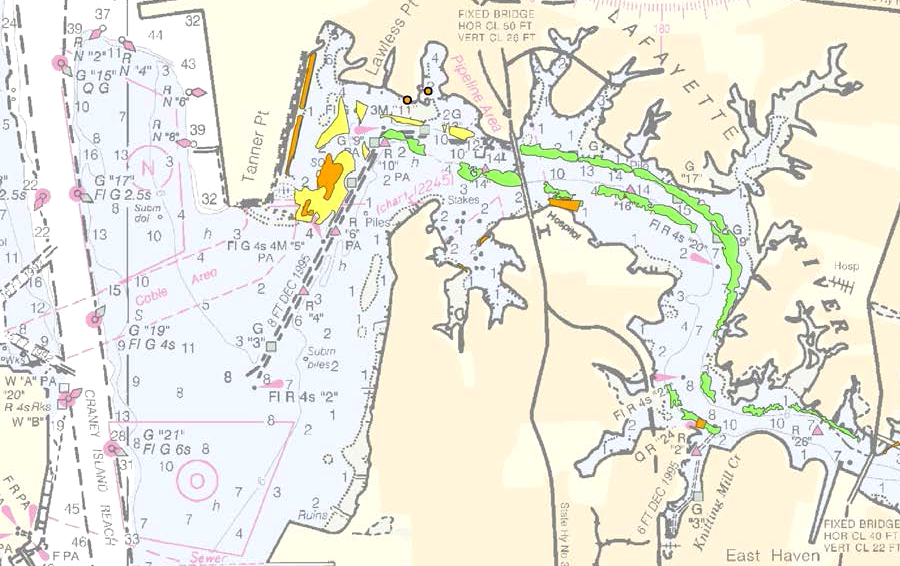

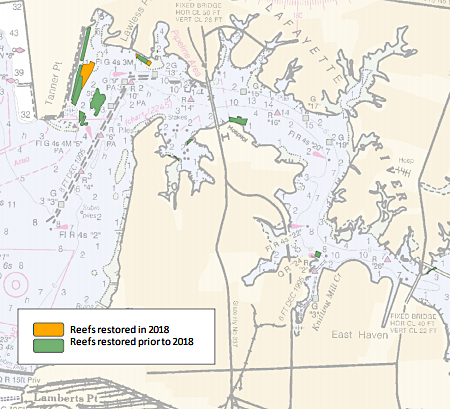

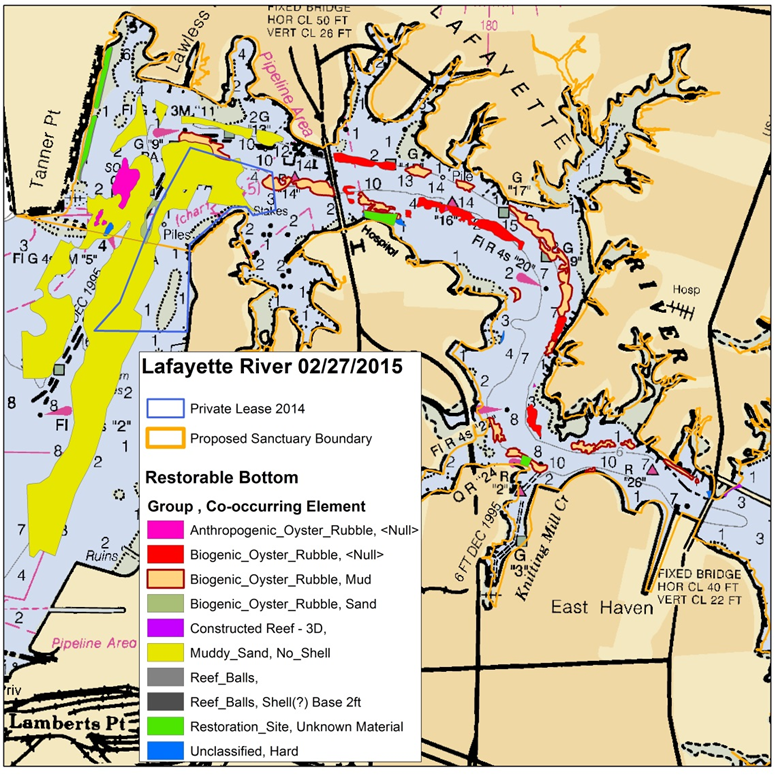

existing oyster reef restoration projects (orange), relict reefs (green), and prime restoration bottom (yellow) in the Lafayette River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Integrated City of Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement (Figure 10-22)

Though the state was unwilling to contribute oyster shells in 2011, restoration efforts have continued on the Lafayette River. In 2014, scientists discovered evidence that vertical oyster reefs can rebuild naturally if not disturbed or harvested. An underwater survey of the Lafayette River revealed 10 natural oyster reefs populated by native oysters. Watermen had not harvested oysters from the polluted, urban river in 80 years, and somehow during that time the oyster population recovered naturally.19

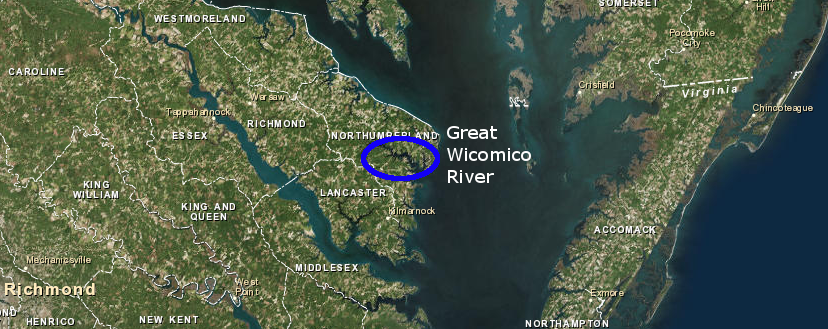

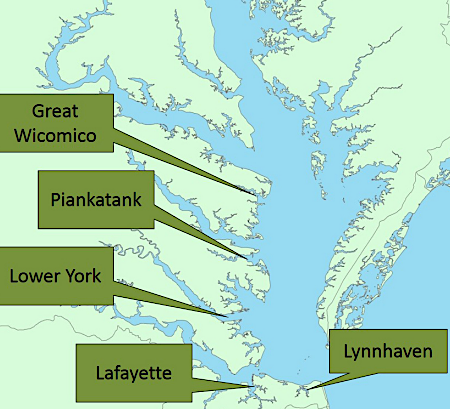

In the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement, Maryland and Virginia each committed to restoring oyster reefs in five rivers by 2025. Maryland started with oyster sanctuary sites on two tributaries of the Choptank River, Harris Creek and Tred Avon, plus the Little Choptank River and St. Mary's River. Breton Bay on the Potomac River was chosen as well. Biologists then discovered few living oysters there, suggesting the habitat was unsuitable, so that site was dropped and the Manokin River was chosen instead.

Maryland's last project was also its biggest. It planned to plant oysters on 441 acres of river bottom along 25 miles of the Manokin River, in what would be the world's largest restoration project.

However, watermen remained upset that the once-abundant oyster beds on the Manokin River had been declared off-limits in 2010. The state planned to use granite rocks as the solid substrate for oyster spat for one-third of the project acreage. Watermen complained that granite blocks would snag the baited trotlines used for crabbing, which was allowed in Maryland's oyster sanctuaries. Somerset County officials filed suit in 2021, claiming the county owned the submerged land where the state was planning the oyster sanctuary.

The lawsuit delayed Maryland's plan to fulfill its 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement commitment to restore oysters on five rivers.20

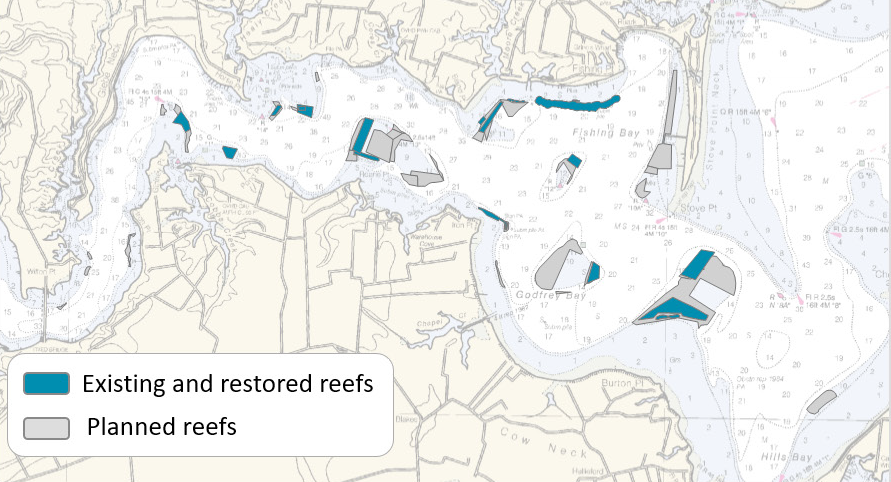

The five sites chosen by Virginia were on the Lafayette, Lynnhaven, Piankatank, Lower York, and Great Wicomico rivers. Western Shore Oyster Restoration Workgroup focused on the Piankatank, Lower York, and Great Wicomico rivers, while the Hampton Roads Oyster Restoration Workgroup tackled the Lafayette and Lynnhaven rivers. Metrics were established to define "success." Metrics for the Wicomico River were::21

Virginia committed in 2014 to complete oyster restoration in five rivers, and achieved success in the Lafayette River in 2018

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2018 Virginia Oyster Restoration Update

Private funds were required, in addition to Federal, state, and local resources. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation gave $200,000 to Lynnhaven River Now and the Elizabeth River Project in 2018, helping those local organizations continues their recovery projects.

The first declaration of success was for the Lafayette River, where careful surveying identified hard river bottom which could support an oyster population. The target of 12 acres was achieved in 2018.

selecting restoration sites required identifying areas with a hard substrate and where sedimentation would not cover the spat

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Oyster Restoration Geodatabases, Lafayette River Restorable Bottom Criteria (Figure 1, December 2020)

The Lynnhaven River Now project focused on the Lynnhaven River. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation planted 470 million spat-on-shell oysters on 12 new reefs, covering 32 acres, created by the Elizabeth River Project with recycled shells, granite and crushed concrete on the sandy bottom. On average an 18-inch-diameter reef ball ended up covered with more than 2,000 oysters. Because scientists found 48 more acres of existing "historic" reefs, the initial restoration target of 80 acres with an oyster density of 50 oysters per square meter was achieved far quicker than expected.

On the Great Wicomico, 122 acres were restored.

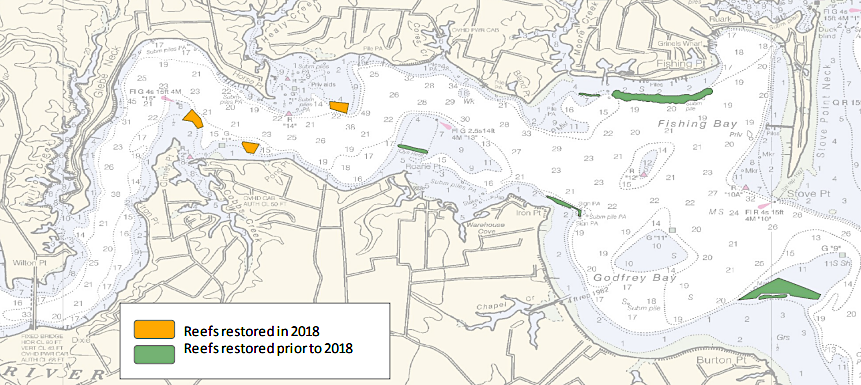

by 2020, oysters had been restored on 100 acres of the 122-acre target on the Great Wicomico River

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Great Wicomico River Oyster Restoration Tributary Plan (Figure 1, December 2020)

The Elizabeth River Project's volunteer efforts led to an extra, sixth restoration initiative on the Eastern branch of the Elizabeth River. Nearly 24 acres of new oyster reef was created there.22

The other large Federal-state debate was over Virginia's proposal to import an Asian species (Crassostrea ariakensis) to replace the native species, (Crassostrea virginica). State officials assumed Dermo and MSX had permanently damaged the Eastern oyster that had evolved in the Chesapeake Bay, while the Suminoe oyster originally from the China Sea was resistant. If the limiting factor in the Chesapeake Bay was not the loss of habitat but the pressure of disease, then introducing a disease-resistant oyster was thought to have both economic and environmental benefits.

the Virginia Department of Health bans shellfish harvesting throughout Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Department of Health - Shellfish Closure and Shoreline Survey Documents, Shellfish Area Condemnation #056-007

Federal officials required completion of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before authorizing the release of the Asian oyster, to assess if new virus or other diseases might be introduced at the same time. The EIS assumed the goal was to be able to harvest 5 million bushels/year from the entire bay, roughly comparable to harvests between 1920's-1970's before Dermo and MSX devastated the population. At the time of the EIS, the existing population in the Chesapeake Bay was less than 10% of the desired number (12 billion market-size oysters).23

The slow, five-year EIS process frustrated state officials, but led to the key discovery that has enabled recovery of the oyster population.

The environmental analysis required evaluating comparable versions of the Asian and native species. To protect against an accidental introduction, a sterile version of the Asian oyster was used to see how it would grow in the Chesapeake Bay. Since the Asian species had been genetically modified to have a third set of genes to make it sterile, a "triploid" version of the native species (with 30 rather than 20 chromosomes) was needed. Standish Allen, at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center and the person who discovered in 1979 how to create triploid oysters, produced sterile versions of both species and distributed them for testing around the bay.

Growers discovered that the triploid version of the Eastern oyster grew substantially faster than the normal diploid version, since no energy was diverted to spawning (one reason that eating oysters was not recommended in the summer months that do not have an "R" in their name). The triploid version matured within 18 months, so fast that it was ready for harvest before being damaged by Dermo and MSX. The testing process trained a critical mass of people in how to grow oysters with intensive management using cages that floated from docks, a revolutionary change from the traditional scatter-shell-and-see-what-grows-on-the-bottom process.

After realizing that the native species was as suitable as the Asian one, the Corps - with the support of Maryland and Virginia - rejected the proposal to import the Asian species. Oyster growers, already experienced in using the gear for the Crassostrea ariakensis tests, switched to growing the triploid version of the native species. Aquaculture has boomed, and now offers one path for getting to the target of 12 billion market-size oysters in the bay.24

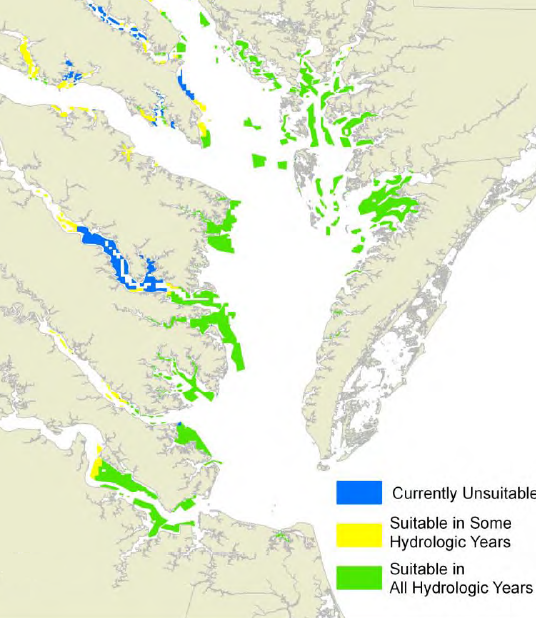

The Federal and state agencies proceeded to develop a Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan. However, "Save the Bay" efforts will not restore all 232,016 acres of the original habitat for oysters that were documented in the 1892-1894 Baylor surveys.

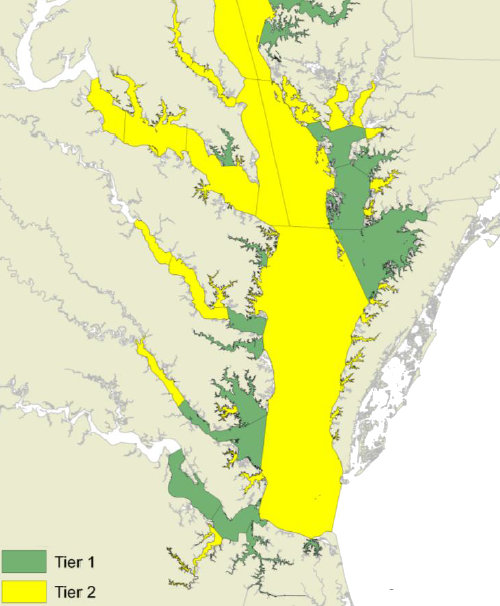

The oyster restoration plan defined a numeric target for the area to be set aside as sanctuaries: 20-40 percent of historic habitat, equivalent to 8-16 percent of the land designated as Baylor Grounds in Virginia and Natural Oyster Bars by the Yates surveys in Maryland. The US Army Corps of Engineers clarified that it had no authority to create new sanctuaries; that was a state role. Federal efforts in Virginia would be focused on existing sanctuaries in 10 tributaries with high-salinity water, designated Tier 1 sites:25

Location | Restoration Target (Acres) |

| Great Wicomico River | 100-400 |

| Lower Rappahannock River | 1,300-2,600 |

| Piankatank River | 700-1,300 |

| Mobjack Bay | 800-1,700 |

| Lower York River | 1,100-2,100 |

| Pocomoke/Tangier Sound | 3,000-5,900 |

| Lower James River | 900-1,800 |

| Upper James River | 2,000-3,900 |

| Elizabeth River | 200-500 |

| Lynnhaven River | 40-150 |

the Tier 1 areas for oyster restoration at sanctuaries do not include Virginia's portion of the Potomac River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery: Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan - Maryland and Virginia

By 2012, 2,214 acres of oyster habitat had been restored in Virginia. That was less than 2% of the 121,000 acres of restorable habitat identified by the oyster restoration plan that was within Baylor Survey areas reserved for public use. Though oysters can build their own habitat by creating reefs, in the Chesapeake Bay the substrate is disappearing naturally (dissolving in the water, or sinking into the soft sediments) faster than oysters are replacing it.

Restoration of 10 tributaries was included in the state's Watershed Implementation Plan, to comply with the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) established with the Environmental Protection Agency.

A significant new source of funding was provided in 2020. The state budget included $10 million in capital funds for the first time to restore oyster beds, defining them as natural infrastructure. Governor Northam commented:26

Source: Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Nansemond Indian Nation: Restoring Connections Through Oysters

As sea level rises, the challenge of oysters to maintain their existing habitat is increased. Human placement of granite or other hard material on submerged lands can mitigate the loss of calcium-based substrate.

In 2007, two scientists published a provocatively-titled study, "Why Oyster Restoration Goals In The Chesapeake Bay Are Not And Probably Cannot Be Achieved." They noted that it would be impossible to restore the ability of the oysters a century ago to filter the entire volume of the Chesapeake Bay in three days, and the most optimistic expectations should be a modern equivalent of 14-28 days. They identified only one location in the entire bay that was healthy enough to support regular commercial harvest, the Burwell Bay region of the James River.27

Burwell Bay has the most-sustainable oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay watershed

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Another study in 2015 identified a previously-unrecognized threat that might limit restoration in shallow waters. The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center determined that "dead zones" can appear in creeks and rivers as shallow as 20' deep, as well as deep waters on the Chesapeake Bay. After the sun sets in the evening, oxygen is continuously removed from the shallow water by the respiration of animals and plants and decay of material on the bottom - but no oxygen is provided by photosynthesis.

When wind and currents do not stir the shallow waters sufficiently, brief periods of time without oxygen occur in shallow waters once thought to be safe places for creating new reefs. Research was conducted in the "Room of D.O.O.M." (Dissolved Oxygen Oyster Mortality), and as one restoration leader noted:28

new reefs have been planted in the Piankatank River

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2018 Virginia Oyster Restoration Update

Microplastics in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries are another threat to oysters. Polyester, nylon, and other plastic material in clothing will releases microfibers (less than 5mm in diameter) and microbeads (less than 1mm in size) into washing machines. Wastewater discharged by treatment plants will intercept a portion of the plastic residue, but discharge some down surface streams.

Oysters ingest the plastic pollution as they filter the water to feed. The plastic provides no food value to oysters. There was concern that the plastic particles would block digestive tracks or reduce the uptake of nutrients and slow oyster growth. Research in the early 2020's indicated that oysters excreted the plastic about as fast as the material was ingested, and no clear impact was discernable.29

plastic microfiber/microbead pollution does not appears to limit oyster growth, and plastic baskets can be useful cages

Source: Wikipedia, Oyster Farming

Restoration is expensive. Costs for building 12-inch high reefs and seeding them with spat are estimated a $1.0 billion-$3.6 billion for just Virginia. Costs would be higher if sanctuaries were located in low salinity tributaries, where oyster reproduction is lower. Meeting all oyster goals for ecosystem restoration in the Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration Executive Order (E.O. 13508) could cost $1.6 billion-$5.4 billion in Virginia.30

One way to reduce costs would be to utilize a "direct setting" approach. The traditional approach was to grow larvae in aquaculture laboratories and then have them attach to shells, before placing young oysters into the water. "Direct setting" involved putting larvae directly into the water above an existing reef, artificial or natural. If enough larvae managed to attach themselves to a hard object, then the time required to grow spat in an aquaculture laboratory could be minimized.

A 2019 experiment determined that at least some larva released for direct setting did end up on the reef.31

Of the three causes for the decline of the oyster in the Chesapeake Bay - over-harvesting, disease, and habitat loss - restoration of habitat will be the most expensive technique to re-establish a sufficient number of oysters to meet ecological objectives. If funding for restoration is used for dual purposes, including perpetuating a "put and take" fishery where oysters are removed by commercial harvesting, then the costs will be even higher.

Source: Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Back to Baysics: Oyster Sanctuaries

Aquacultural operations that raise fish create artificially-high concentrations of animals that allow disease to spread. Oyster aquaculture may have the opposite effect.

Oysters naturally establish reefs and live in high concentrations. The concentration levels are less significant than the age of the oysters for the risk of infection by Demo and MSX. Those diseases take several years to infect maturing oysters.

Oyster aquacultural operations harvest oysters before they become diseased. A study in 2018 concluded that the harvesting cycle might reduce the presence of those diseases in the wild, and:32

restoring oyster reefs requires hauling shells to plant spat

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Chesapeake Bay Partners Have Restored 1,220 Acres of Oyster Reef and Chesapeake Bay: Oyster Restoration

In 2020 the Chesapeake Bay Foundation debuted a new technique for creating oyster reefs. It created the Mobile Oyster Restoration Center, which consisted of two barges with over 7 million baby oysters growing in six tanks placed on top of the barges.

Natural oyster shells or concrete balls inside the tanks were seeded with oyster spat, then transported to a restoration site. The tanks were lowered by crane onto the bed of a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay or, on the eastern edge of the Eastern Shore, the Atlantic Ocean. That process eliminated the need to remove seeded shells from the tanks at the foundation's Virginia Oyster Restoration Center at Gloucester Point, transport them to an artificial reef location, then drop them through the water column to the bottom.33

the plan to restore 438 acres of oyster reef on the Piankatank River was the largest such project in the world

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, 2019 Virginia Oyster Restoration Update and Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Box 13: Piankatank

By the end of 2021, the creation of artificial reefs had been completed on the Lafayette, Piankatank, Great Wicomico, and Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River. The creation of 438 acres of restored oyster reef on the Piankatank River was the largest such project to date in the world, but that river still had far less than the 7,000 acres being harvested after the Civil War.

State agencies were confident that the projects on the lower York and Lynnhaven rivers would be completed by 2025. Virginia had committed in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement to create oyster reefs on five rivers, and in 2020 added the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River as well.34

fourth graders from Virginia Beach's Seatack Elementary School partnered with the Corps of Engineers to grow 60 bushels of oysters in 2011-12 for a reef in the Elizabeth River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 120402-A-ET072-028

The target in the Lynnhaven River was to create 152 acres of oyster reef. Because natural oyster shell was unavailable, the Lynnhaven River Now organization chose to recycle concrete for the Lynnhaven River Reef Replenishment Program. The concrete came from a mountain of construction rubble over 60 feet high which had accumulated along Interstate 264, until the City of Virginia Beach forced the landowner in 2021 to remove the eyesore.

Some ended up in a one-foot high artificial reef underneath the waters of the Lynnhaven River, providing habitat for oyster spat. Water circulation in the Lynnhaven River naturally recycled oyster spat within the river, creating more opportunity to find a hard surface and grow into a mature oyster. As a "trap estuary," the river was a good site for investment in oyster restoration.35

Lynnhaven River was a good site for restoration in part because it is a trap estuary, where river circulation helps to retain oyster larvae

Source: Lynnhaven River NOW, Army Corps of Engineers Oyster Reef Restoration

The Chesapeake Oyster Alliance, which included a wide array of businesses, educational institutions, non-government organizations, and oyster growers, set a target in 2018 of adding 10 billion oysters to the Chesapeake Bay by 2025. It encouraged small-scale efforts like oyster gardening projects. The 100 partners in the Chesapeake Oyster Alliance were halfway to the target in 2022, and 6 billion oysters had been planted on the bottom of tributaries and the bay itself by 2024.

The alliance projected that water quality would be improved by adding the 10 billion oysters:36

By April 2024, reef restoration was completed on the lower York River. That added 200 more acres, and was the eighth of 10 rivers in the 2025 goal - plus Virginia's decision to add the Elizabeth River as a bonus. In the previous decade, Maryland and Virginia together had added 1,572 acres of oysters. Still remaining to be restored at the end of 2024 were the Manokin River in Maryland (222 acres) and the Lynnhaven River in Virginia (38 acres).

The Nansemond Indian Nation was participating in the restoration process as well as state/Federal agencies and non-government organizations. It was one of the participants in the Chesapeake Bay Foundation's Oyster Gardening Program, and in 2024 added 9,000 oyster shells coated with spat to one of three reefs in Chuckatuck Creek established by the Nansemond River Preservation Alliance.37

Statewide, in 2024 over 100,000 oysters were transferred from private aquaculture "gardens" into the Chesapeake Bay. Across the bay, one billion oyster spat were added annually by a wide range of partners. Between 2017-2024, the total number of oysters added to the bay has totaled over six billion. The Chesapeake Oyster Alliance goal was to reach ten billion by the end of 2025.38

In 2025, Maryland finished planting oysters in a sanctuary on the Manokin River. That completed the target of 10 tributaries, with five in Maryland and five in Virginia. Virginia added the Elizabeth River to exceed its original commitment in tributaries. After discovering that roughly 500 acres planned for restoration already had an acceptable population, the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement reduced the goal from 2,400 acres to 1,800 acres.

Virginia ended up planting oysters on 1,059 acres, at a cost of $22 million. Maryland planted 1,333 acres, at a cost of over $100 million. The cost difference was due in part to the requirement for Maryland to plant far more oysters per acre, because the salinity in that state's portion of the Chesapeake Bay was lower and fewer planted oysters would survive.39

oyster shell can be barged to a reef restoration site, then washed overboard

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

Palace Bar Reef at the mouth of the Piankatank River is marked on nautical charts

Source: OceanGrafix, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Nautical Chart 12235

low levels of dissolved oxygen makes much of the Rappahannock River unsuitable for oyster restoration

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers - Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan, Briefing to Shellfish

Advisory Committee (April 2012)

candidate locations for oyster restoration at mouth of Rappahannock River

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Virginia Oyster Reef Restoration Map Atlas (2002)