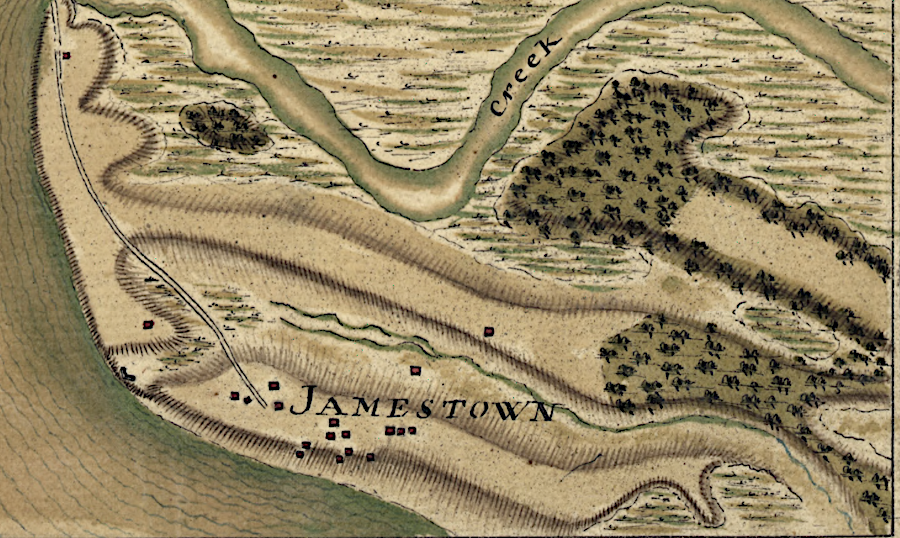

French troops in 1781 mapped structures on Jamestown Island next to the shoreline

Source: Library of Congress, Plan du terrein à la rive gauche de la rivière de James vis-à-vis Jamestown en Virginie ... (by Jean Nicolas Desandrouins, 1781)

French troops in 1781 mapped structures on Jamestown Island next to the shoreline

Source: Library of Congress, Plan du terrein à la rive gauche de la rivière de James vis-à-vis Jamestown en Virginie ... (by Jean Nicolas Desandrouins, 1781)

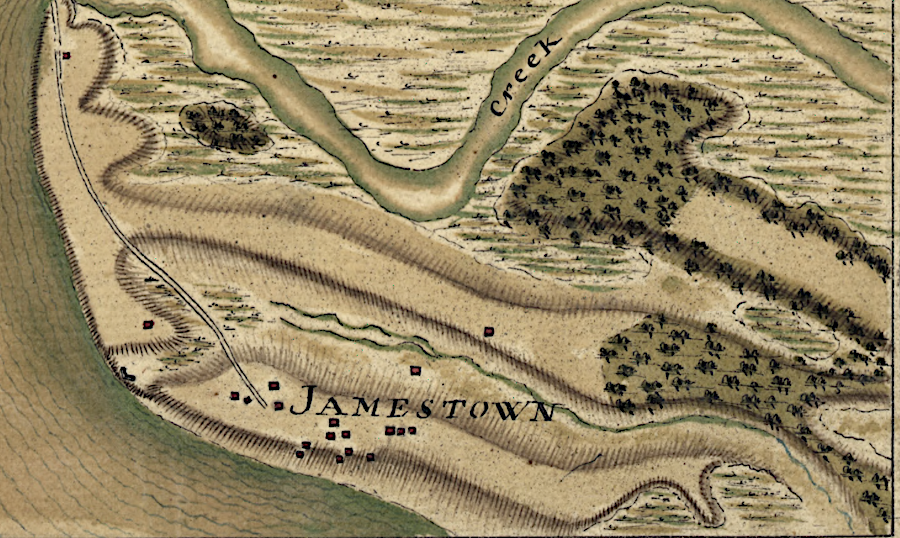

A seawall was constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1901 to protect Jamestown Island. The seawall was extended in 1906 to protect the presumed location of the southeastern corner of the palisade that protected Jamestown.

James River shoreline at Jamestown before the seawall was constructed in 1901-1902

Source: Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Jamestown in 1907

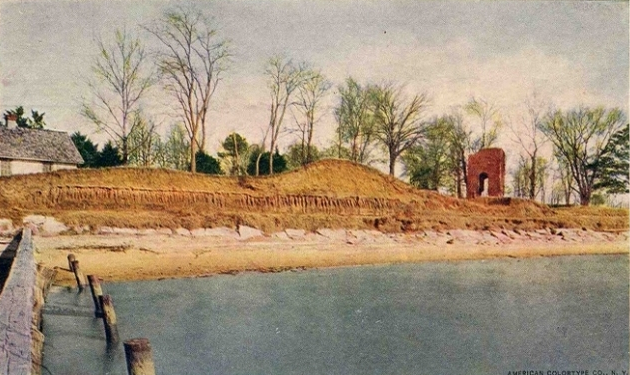

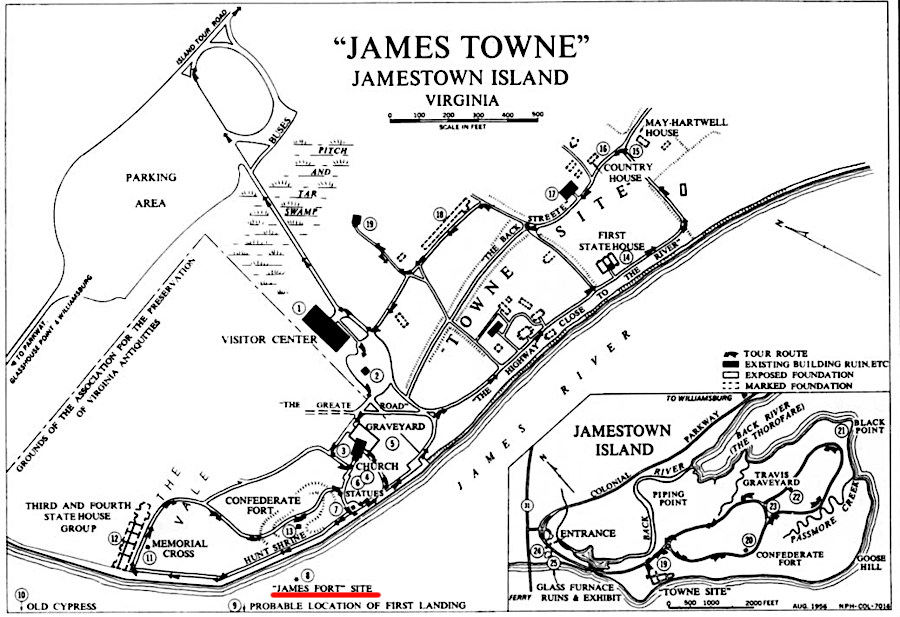

At the start of the 20th Century, the conventional wisdom assumed that the historic 1607 fort had already disappeared from erosion. A single cypress tree in the James River, 100 yards from the western shore of Jamestown Island, was thought to mark the shoreline where English colonists had tied their ships to trees:1

until 1994, the 1607 fort at Jamestown was thought to have been lost due to erosion

Source: National Park Service, Historical Handbook Number Two (1957)

The members of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the elite white women concerned with protecting key historical sites in Virginia after the Civil War, took the lead in preserving Jamestown. The group assumed the place still retained great significance even if the fort had eroded away.

Mr. and Mrs. Edward E. Barney donated 22.5 acres to the group, including the brick church tower, in 1893. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities was successful in getting the US Congress to appropriate $10,000 for a breakwater in the 1894 Rivers and Harbors Act. Large granite stones were placed along shoreline. In addition, wooden fences were built perpendicular from the shoreline into the river, to slow the currents and increase sediment deposition rather than erosion. Evidence of four of those fences are still evident at Jamestown today.

Storms washed away the soil around the large breakwater stones. They moved away from the shoreline and no longer provided protection, so the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities convinced the US Congress to fund a seawall.

Colonel Samuel H. Yonge of the US Army Corps of Engineers was responsible for the seawall construction project in 1900-1901. He was particularly interested in the history of the site, and published his research and maps in time for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition celebrating the 300th anniversary of the arrival of English colonists.

Col. Yonge determined that the erosion of Jamestown Island had started as far back as 1686. He attributed the erosion to wave action rather than tidal currents. The average tidal range was 22 inches. That was enough to submerge the isthmus that connected Jamestown to the mainland and make it appear to be an island at high tide, but not sufficient to erode the clay soil significantly.

Winds created waves in the wide James River, and those waves washed away the island. Once steamboats began traveling up the James River in the mid-1800's, erosion accelerated from two feet annually to four feet.2

seawall in 1907, at the 300th anniversary ("tercentennial") of the construction of James Fort

Source: Samuel H. Yonge, The site of old "James Towne," 1607-1698: A brief historical and topographical sketch of the first American metropolis (1957)

The Federal government got involved in managing the site three decades after building the seawall. In 1930, President Hoover used his executive authority to proclaim the remaining 1,560 acres on the island as Colonial National Monument, and the National Park Service acquired that acreage in 1934. Two years later, the US Congress designated the site as Colonial National Historical Park.

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities signed a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service in 1940. The Association - now known as Preservation Virginia - established the "Historic Jamestowne" partnership with the National Park Service in 2007, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of English colonists.3

The assumption that the fort had eroded away with 20 acres of the island was disproved starting in 1994. Archeological investigations have revealed that only a corner of the fort was actually "lost."

The rediscovered fort was at still at high risk. Sea level rise was expected to continue to alter the landscape. Rising waters had already flooded two of the 59 historic structures and archaeological sites, while damaging 24 others. All but two would be flooded by 2065, and most of Jamestown Island would be underwater by 2100. In 2022, the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed Jamestown as one of the "11 Most Endangered Historic Places for 2022."4

Source: Jamestowne Rediscovery, Losing Ground: Jamestown Before the Seawall – Dig Deeper, Episode 22

A 2021 engineering study identified that the seawall was at risk of collapse. Surprisingly, the engineering study and salinity testing showed the threat to the seawall was from rainwater. Intense rain events raised the water table on the island. Pressure from groundwater was pushing the concrete slope of the seawall out of alignment.

In response, Preservation Virginia raised $2 million to reinforce the seawall. Chunks of granite, each weighing 500-1,500 pounds, were barged to Jamestown Island placed against the river side of the seawall. The extra weight was designed to prevent blocks of concrete from sliding out of place. The director of collections and conservation for Jamestown Rediscovery said plainly:5

There are archeological resources on the bottom of the James River outside the seawall that protects the archeological resources on Jamestown Island. An underwater survey at Colonial National Historical Park in 2006 identified 26 shipwrecks plus landings, wharves and piers. Shifting sediments and river currents have not destroyed all the heritage that is underwater.6