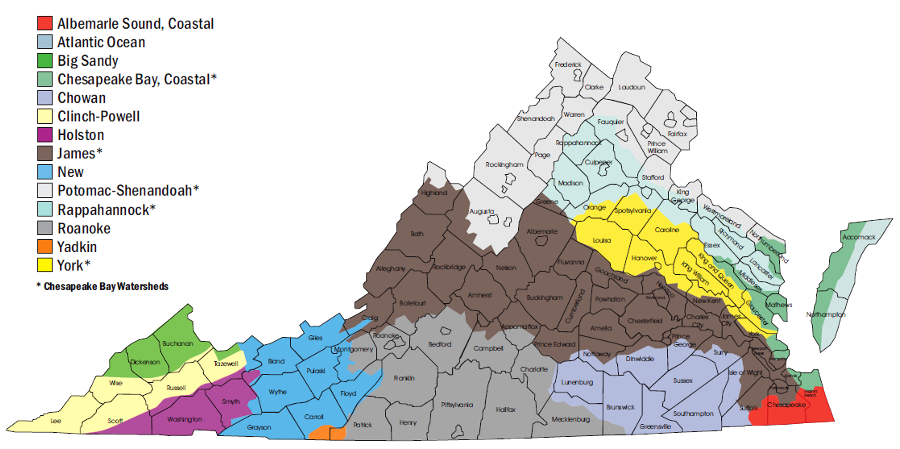

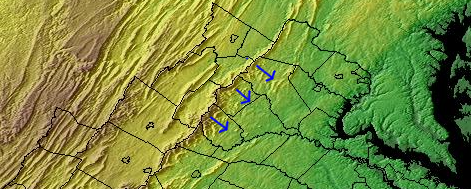

major watersheds of Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Watershed Map

major watersheds of Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Watershed Map

Watershed management is the basis for many environmental protection decisions. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) even has a Watershed Academy. The Federal agency has responsibility for implementation of many water pollution control laws, overseeing all states to ensure no locality attracts business unfairly by allowing excessive amounts of pollution.

The differences in boundaries between watersheds and states/counties complicates the efforts to control pollution. "Everyone lives downstream" - but sometimes the factories or urban areas upstream who generate the pollution are in another state and are not harmed by the bad water flowing away, while those affected by the pollution may have limited political influence to ensure upstream problems are fixed.

For example, a major chemical plant in Saltville (now a Superfund site) degraded the water quality for Kingsport, Tennessee for 80 years. Virginia politicians were well aware that Virginia residents received benefits from operating the plant without paying the costs of controlling the excessive chlorides from salt dumped into the North Fork of the Holston River. Those who suffered from the pollution lived in Tennessee and could not vote in Virginia.

Tennessee officials went to court to force Virginia to impose realistic pollution control standards on the company. It then closed down, eliminating 1,000 jobs in a community of about 2,000 people.1

Three terms in particular are essential in understanding the physical geography of Virginia - watershed, divide, and tributary. No matter where you are on land in Virginia, you are in a watershed, or "drainage basin." The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines watersheds as:2

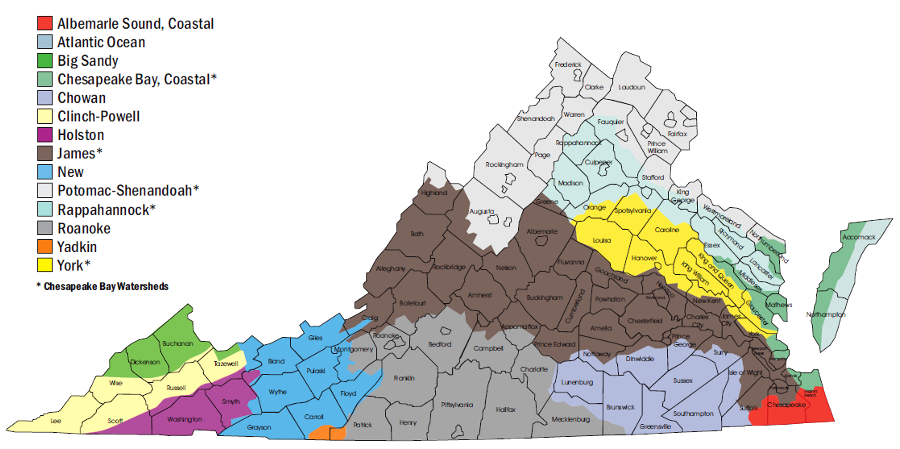

watersheds A and B as defined by roof of Arlington House, at Arlington Cemetery

Source: National Park Service

Elsewhere, the Environmental Protection Agency uses the definition created by John Wesley Powell for a watershed:3

The Code of Virginia defines a watershed:4

A watershed divide is the ridge on the ground that separates watersheds. If you look at a roof, you will see a divide at the top where a ridge directs rainwater towards one side of the roof or another. Many houses built since the 1990's have complex rooflines, so those roofs have multiple watersheds separated by different ridges/divides.

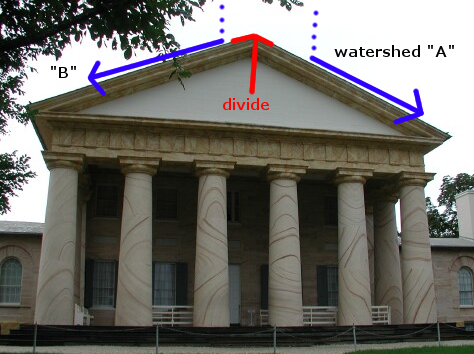

the Blue Ridge is a major watershed divide - rain falling on the east slope flows to the east

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), State Topography Image: Virginia

A tributary is a stream that flows into a larger stream - which might be called a branch, stream, creek, run, or river. The concept is the same, despite whatever names has been adopted for the streams.

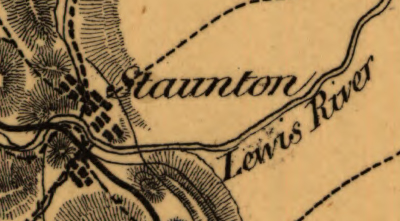

on this 1860's map, Staunton was at the headwaters of Lewis River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the Virginia Central Railroad

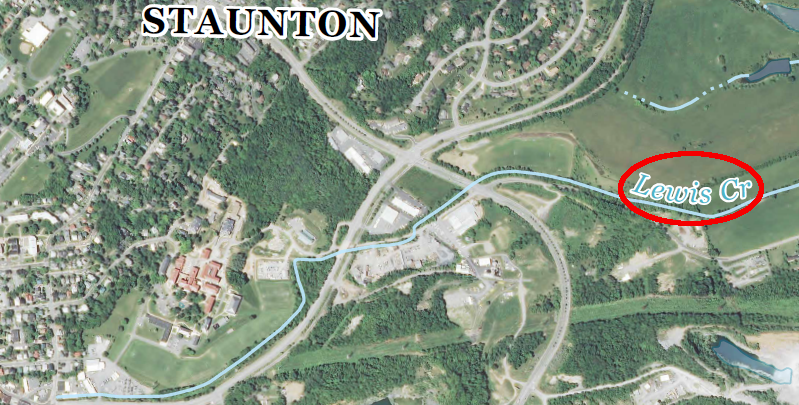

Lewis Creek in Staunton, on a 2013 map

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Staunton 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013, Revision 1)

Tributaries are upstream, and water from tributaries flow downhill on their journey to sea level. In Virginia, all land and water is at or above sea level, unless someone has dug a unnatural deep hole; there are diabase quarries in Northern Virginia that have excavated so deep into the bedrock that the quarry's bottom is below sea level. There is no natural equivalent in Virginia to the Dead Sea in the Middle East, which is in a depression that is over 1,400 feet below sea level.

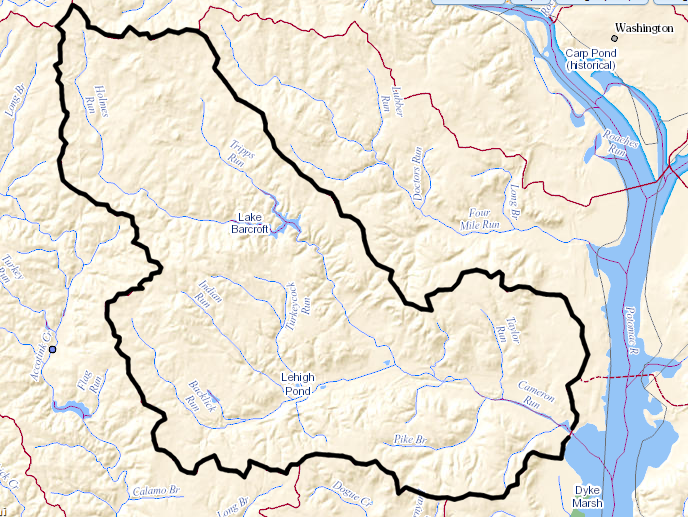

Tripps Run, Holmes Run, Turkeycock Run, Indian Run, and Backlick Run are some of the tributaries flowing into Cameron Run (boundaries of Cameron Run watershed shown in black)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Hydrography Dataset Viewer

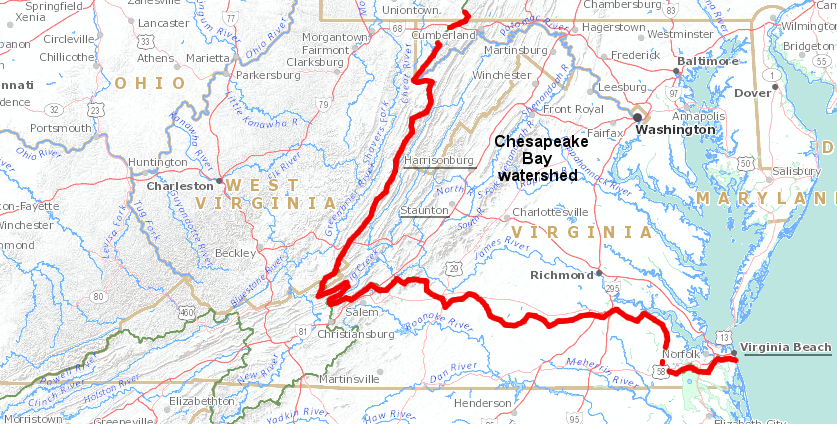

All of Northern Virginia and all of the Shenandoah Valley are in the watershed of the Chesapeake Bay. Most of Virginia south of the James River is not. Raindrops that fall on the campus of Washington and Lee in Lexington or the "grounds" of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville will end up in the Chesapeake Bay. Raindrops that fall on the campus of Virginia Tech in Blacksburg will flow to the Gulf of Mexico, and never get to the Chesapeake Bay.

Staunton and Harrisonburg are in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, but the southern part of Virginia is not - including two of the four watersheds of Virginia Beach

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer; City of Virginia Beach, Southern Rivers Watershed

There is a water fountain next to the Johnson Center on the Fairfax Campus. Some spray can flow away from the fountain, and (if the water does not evaporate) the droplets flow down to the Potomac River. The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, so by definition the Potomac River is a tributary of the bay.

Where water flows, pollution goes. When a smoker flings a cigarette butt onto the ground at the Fairfax campus of George Mason University, the tobacco leaves quickly dissolve - but the filter could float all the way to Virginia Beach. Similarly, oil droplets and metal filings from brake pads that end up on roads and parking lots in Northern Virginia will pollute the local stream, then the Potomac River, then the Chesapeake Bay before ending up in the Atlantic Ocean. Pollution is heavily diluted during the journey, but the campaign to Save the Chesapeake Bay depends upon cleaning up the pollution upstream in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia before excessive amounts of sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorous wash into local streams and then flow to the bay.

pollution from the GMU Fairfax campus travels down the Potomac River and through the Chesapeake Bay, before reaching Virginia Beach

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

According to the Chesapeake Bay Program, the bay has 100,000 separate tributaries, with a large watershed. The streams that drain farmland, suburban subdivisions, and urban centers all contribute pollution downstream to the bay. Pollution from the large watershed is concentrated in the bay, because the:5

the Occoquan watershed is a subunit within the larger Potomac River watershed,

and the Potomac River watershed is part of the even-larger Chesapeake Bay watershed

Source: Fairfax Water, Assessment of Potential Water Supply Impacts From Uranium Mining in Virginia

To understand how watershed boundaries affect pollution, first think of a raindrop. A raindrop falls to the ground and runs downhill, of course. At the paved parking lot at grocery stores and Wal*Mart stores, the raindrops run towards drains. If all the water drains to one outlet, then the entire parking lot is in the watershed of that one drain. The water that falls anywhere on that lot will run downhill to one stream, via that drain and its outlet pipe.

When the rainwater on one side of the parking lot runs towards one drain, and rainwater on the other side flows towards a different drain, then that parking lot has two tiny watersheds with a divide separating them. After a rainstorm, the divide gets driest first as the water drains away. The high spot, the divide is where customers walk to avoid the puddles at the end of a storm.

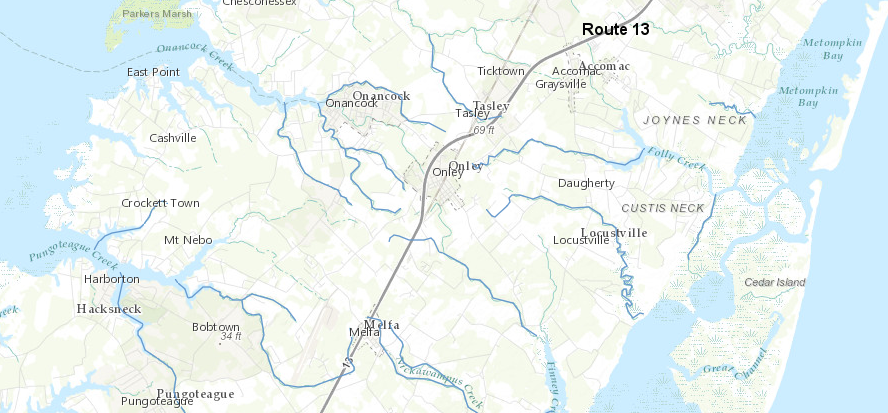

"The divide will dry first" pattern is why roads such as Route 60 goes down the middle of the Peninsula between Richmond and Hampton, and Route 13 goes down the middle of the Eastern Shore. The ridgetops, the watershed divides on those peninsulas are low in elevation, but they are slightly higher than the adjacent land. Farmers who wanted to avoid getting stuck in the mud understood that the original dirt roads would dry quickest at the top of the ridge.

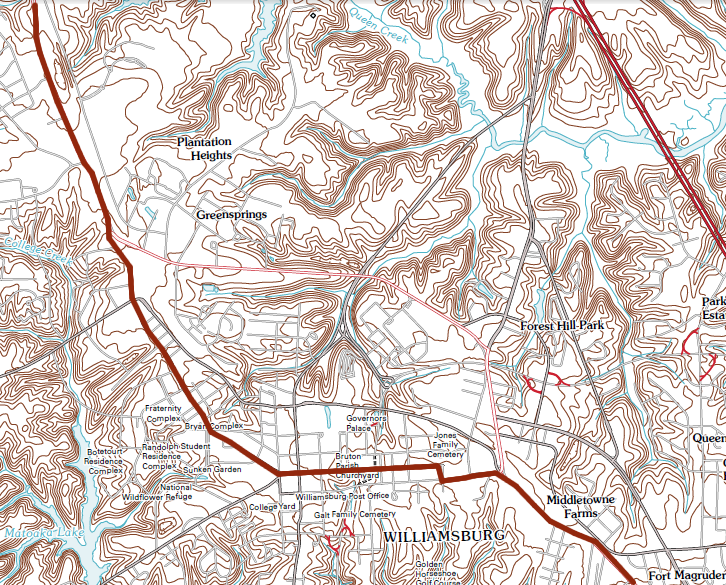

Route 60 between Richmond and Hampton (brown line) was built on top on the watershed divide between the James/York rivers - as was the community of Middle Plantation (now Williamsburg)

Source: US Geological Survey Williamsburg 1:24,000 scale topographic map

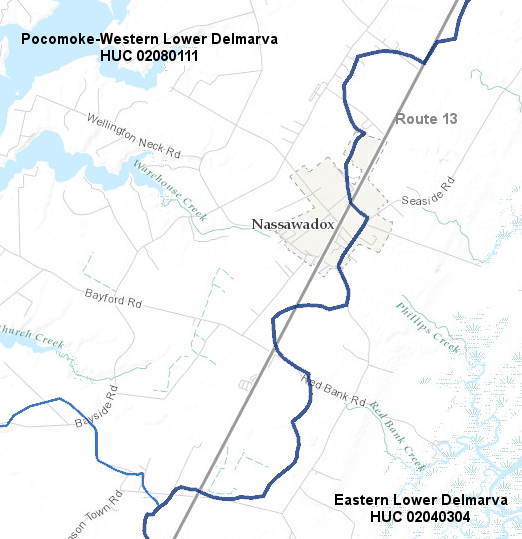

On the Eastern Shore, US 13 follows close to the watershed divide. East of the highway, most of the streams drain directly to the Atlantic Ocean. Most farmland west of US 13 is located in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, where farming practices are affected by efforts to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. Virginia must meet Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) water pollution requirements, reducing runoff of nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorous) and sediments into the bay - so the watershed divide is a key feature on the Eastern Shore.

on the Eastern Shore, Route 13 is located close to the divide... but is not exactly on the watershed boundary

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Hydrologic Unit Explorer

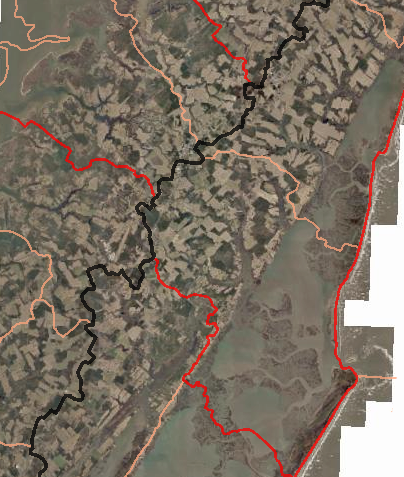

roughly half of the Eastern Shore drains to the Chesapeake Bay, half to the Atlantic Ocean, and the watershed boundary (black line) is in the middle of the peninsula

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Hydrologic Unit Explorer

on the Eastern Shore, much of Route 13 follows the watershed divide, and the route helped the original dirt road dry quickly as well as minimize the number of bridges across creeks

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In Northern Virginia, large parts of Route 7 and Route 50 between Fairfax City and the Blue Ridge follow the watershed divide. The initial road builders chose the relatively-high ridges in part to avoid the cost of building bridges over large creeks, and in part to locate the dirt roads where they would dry quickly after a rain so farm wagons would not get stuck in the mud.

Parking lots look flat, without a sharp "knife's edge" of mountains separating the valleys. Follow the rain as it flows down, however, and the different watersheds associated with different drains will become obvious.

Roads have a "crown" in the middle to facilitate drainage. Athletic fields used for football and soccer games also have a slight rise in the middle, so water will drain away to the sides rather than pool in the center of the field. There is a tiny watershed divide in the middle of the athletic field in every stadium.

A watershed is the area drained by a stream. By that definition, all the land that drains into Pohick Creek, including the majority of the Fairfax campus of George Mason University (GMU), is in the Pohick Creek watershed. Rainfall flows off the impervious surfaces on campus into Rabbit Run, which joins Pohick Creek, which flows into the Potomac River.

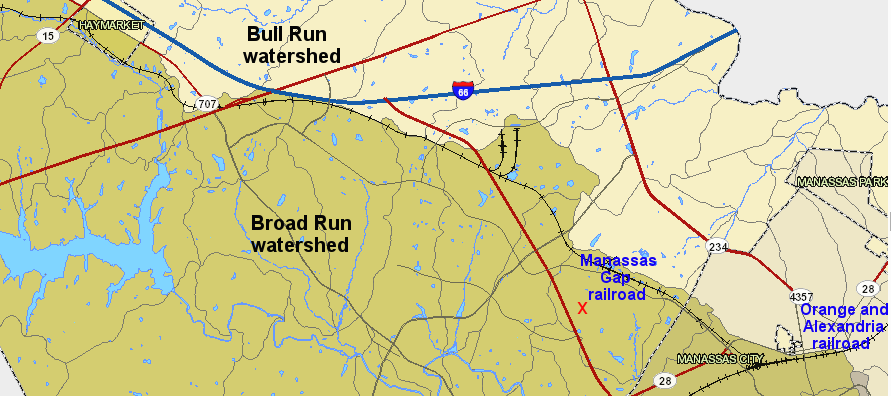

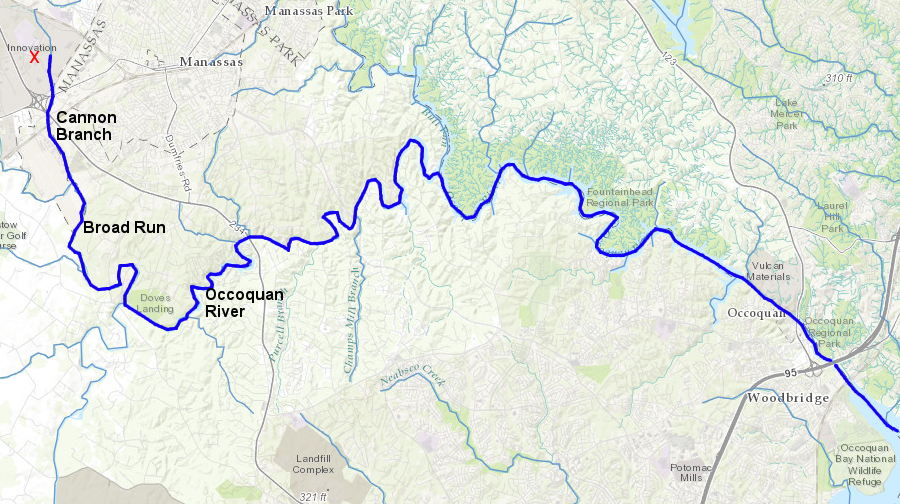

The Prince William campus is in the Occoquan River watershed. Rainwater that falls on the roof of the GMU buildings at the Prince William campus will end up flowing under Freedom Center Boulevard, through the stormwater pond at the Northern Laboratory of the Department of Forensic Science, and down Cannon Branch to the stormwater ponds at the Route 234-Route 28 intersection near the Manassas airport.

When rainfall is sufficient, those ponds will release water into the downstream portion of Cannon Branch, which flows into Broad Run. Broad Run will join with Cedar Run to form the Occoquan River, which has been dammed downstream to create Lake Jackson. The raindrops that flow over the dam will continue downstream to the next dam which formed the Occoquan Reservoir, then over that dam and under I-95 to the Potomac River, and ultimately get to the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

in the 1850's, engineers chose the ridge that divided the Bull Run and Broad Run watersheds as the route for the railroad near the modern Prince William campus of George Mason University (red X)

Source: Prince William County, County Mapper

water running off GMU's Prince William campus (red X) flows into Cannon Branch, which flows into Broad Run, and then into the Occoquan River

Source: Prince William County, County Mapper

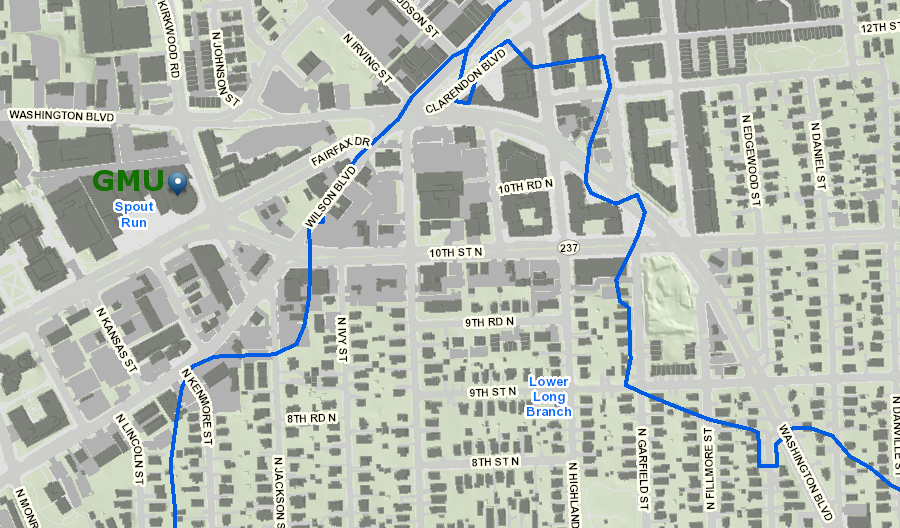

The Arlington Campus of George Mason University is in the Four Mile Run watershed. With all the concrete and asphalt in that urbanized area, it is hard to see the natural topography and hard to recognize watershed boundaries.

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Arlington campus is in the Spout Run watershed, near divides with Rocky Run and Lower Long Branch that are obscured by modern development

Source: Arlington County Map Gallery, Watershed & Resource Protection Areas<

![]() The boundary between watersheds are called a watershed divide. Divides are ridges. Hikers who walk across a divide will go uphill to the top of the divide, and then downhill on the other side. Rainwater goes only in one direction, downhill. Rain that lands on the ridge will flow down one side into one watershed, ending up in a particular stream. Rain landing just a little bit away on the divide will flow down the other side of the ridge, and end up in a different stream.

The boundary between watersheds are called a watershed divide. Divides are ridges. Hikers who walk across a divide will go uphill to the top of the divide, and then downhill on the other side. Rainwater goes only in one direction, downhill. Rain that lands on the ridge will flow down one side into one watershed, ending up in a particular stream. Rain landing just a little bit away on the divide will flow down the other side of the ridge, and end up in a different stream.

For example, rainfall that lands at the top of the Blue Ridge does not sit there, accumulating on the surface in natural lakes. Rainfall flows downhill to the east or to the west. Under the force of gravity, raindrops move initially in "sheet flow" across the surface (most obvious in parking lots...) or by sinking into the soil and then moving downhill while below the ground surface. Ultimately, the water that soaked into the soil will emerge at a spring, joining the rivulets flowing across the surface to form small creeks/streams/runs.

McAfee Knob, looking north into Catawba Creek watershed (draining into James River)

Small "first order" creeks/streams/runs flow together, creating larger branches/creeks/streams/runs and ultimately rivers. In Virginia, there is no consistent logical distinction in size or other characteristics between branches, creeks, streams, or runs. Early explorers and/or local residents chose those labels almost at random, though anything called river will (almost always...) be larger than anything nearby called branch, creek, stream, or run.

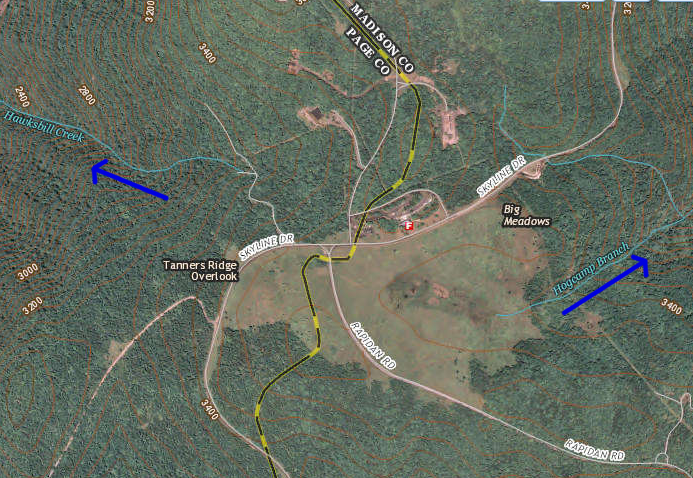

at Big Meadows in Shenandoah National Park, raindrops landing in the meadow will flow downhill to Hogcamp Branch - not uphill into Hawksbill Creek

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map - National Hydrography Dataset

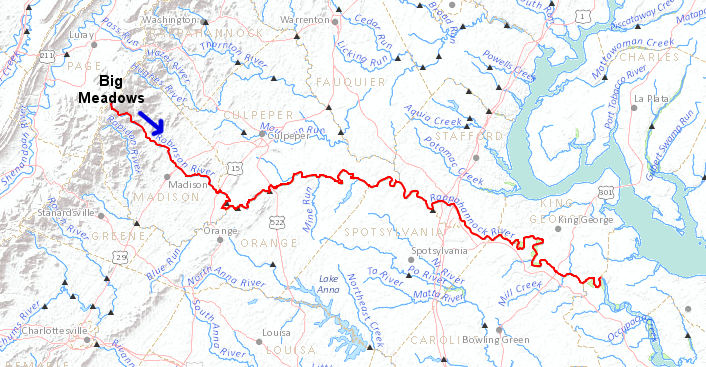

At Big Meadows in Shenandoah National Park, the raindrops that land in the actual meadow across Skyline Drive from the Byrd Visitor Center will flow to the east and form Hogcamp Branch. Hogcamp Branch is a tributary of Rose River, which flows into the Robinson River.

The Robinson River flows into the Rapidan River, which flows into the Rappahannock River, which flows into the Chesapeake Bay, which flows into the Atlantic Ocean. Hogcamp Branch is in the headwaters and in the watershed of each of those rivers downstream. A raindrop landing at Big Meadows will move 3.500 feet downhill on its 100-mile trip to sea level at Fredericksburg, just east of I-95.6

runoff from Big Meadows flows underneath I-95 at Fredericksburg

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas - Streamer

Rainfall that lands on the parking lot for the Big Meadows lodge, campground, and picnic area west of Skyline Drive will flow westward across the pavement and the land into small rivulets that have been etched into the hillside after eons of erosion. The small rivulets ultimately join to form Little Hawksbill Creek or Hawksbill Creek.

Those creeks flow down the west face of the mountain, into the Page Valley, and then into the South Fork of the Shenandoah River at Luray. The mouth of Little Hawksbill Creek and the South Fork of the Shenandoah River in one of many "confluences" with tributaries, increasing the volume of the water flowing down the South Fork of the Shenandoah River.

Big Meadows and the lodge in Shenandoah National Park is at the watershed divide, at the headwaters of different streams that flow downhill in multiple directions

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Big Meadows 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (Revision 1, 2013)

Gravity does not quit working just because a mountain stream has reached the valley and, after a confluence, a tributary no longer retains its name. Raindrops that flow into the South Fork of the Shenandoah River continue to flow down the valley, flowing "up the map" to the north.

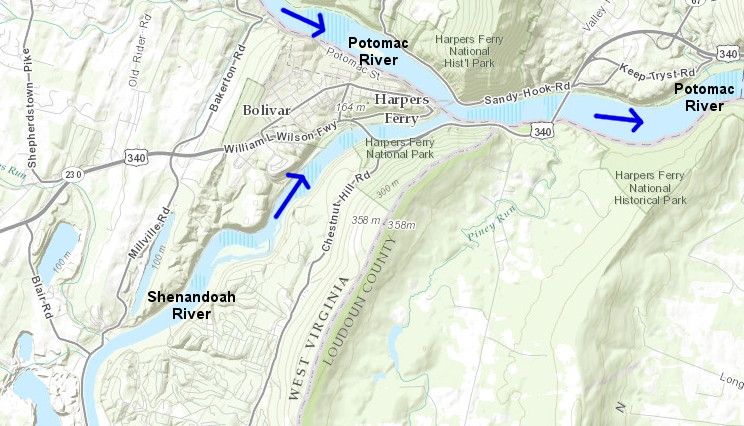

At Front Royal, the South Fork and the North Fork join to form the main stem of the Shenandoah River, which keeps flowing north to Harpers Ferry. The water from the parking lot at Big Meadows will end up reaching sea level when it flows past the Fall Line at the District of Columbia. Every raindrop from the top of the Blue Ridge in Shenandoah National Park that stays in the stream channel, every drop that is not lapped up by a thirsty deer or absorbed by a plant root or evaporated into the atmosphere, will reach the Chesapeake Bay and finally the Atlantic Ocean.

confluence of Potomac and Shenandoah rivers at Harpers Ferry

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

By definition, the confluence is where streams join, where they flow together and at least one stream loses its name. Below the confluence at Harpers Ferry, there is no Shenandoah River. The rain that landed at Big Meadows and washed down the western slope of the Blue Ridge will continue to flow downhill/downstream past Harpers Ferry, but that water flowing below Harpers Ferry is labelled the "Potomac River."

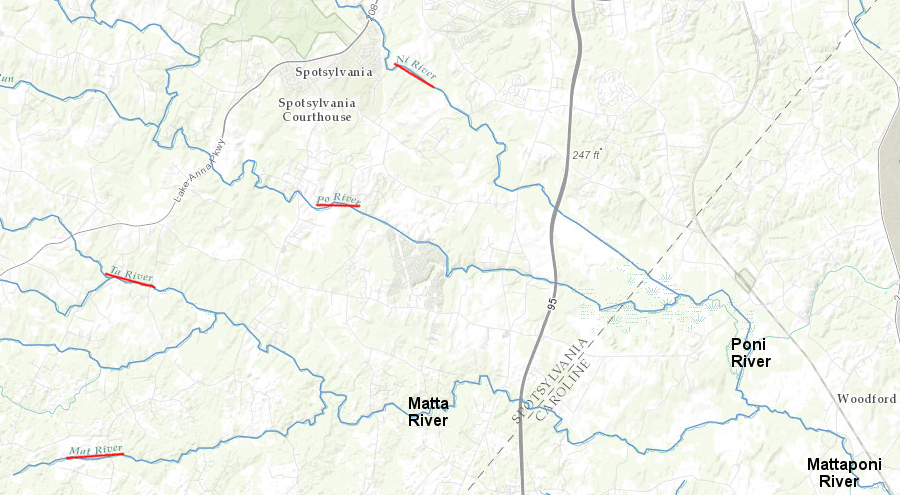

Names of streams that flow together are not hyphenated, like last names may be hyphenated when two people get married. If the custom was to hyphenate all the streams through which water flowed before reaching a place, the stream flowing past Jamestown could be called the Jackson-Cowpasture-Maury-Rivanna-Appomattox-James River. The closest example of cumulative naming in Virginia is the Mattaponi River, whose separate tributaries are the Mat, Ta, Po, and Ni rivers.

the Mattaponi River is formed by four tributaries, the Mat, Ta, Po, and Ni rivers

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In some areas of the western US, streams flowing out of the mountains may dry up before reaching the ocean. In Utah, many streams flow into the Great Salt Lake or equivalent small lakes where the water evaporates, rather than flows on to the Pacific Ocean. As the stream leaves the mountains, the volume of the water in the stream channel may get smaller rather than larger, until the stream dries up completely at a salt flat or sink.

In Virginia, nearly every stream will get larger as it flows downhill and other streams flow into it, ultimately forming rivers and reaching the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic Ocean. The main Virginia exception to the "streams get bigger" rule is in karst topography, where streams might disappear or sink into the ground before flowing underground through porous limestone.

Sinking Creek, west of Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, is in karst topography. Near Sinking Creek, water on the surface may flow into sinkholes in the limestone. On the surface, there is no stream connecting the sinkhole with any creek, but underground the water is still flowing downhill. It will reappear in a spring near the creek, or bubble back to the surface in the streambed itself.

During the winter, when water flows are higher, the surface flow in Sinking Creek goes all the way to the New River. In the summer, water may flow in the channel of Sinking Creek upstream of US 460, but near the mouth of the stream there will be nothing but river gravel in the streambed. The water has disappeared underground, and will emerge from springs in the bed of the New River.

Sinking Creek west of Blacksburg, Virginia

(note topographic contours with hatch marks, showing sinkholes north of the creek)

Source: US Geological Survey, Eggleston 1:24,000 topographic map

Virginia watersheds

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Water Monitoring Day

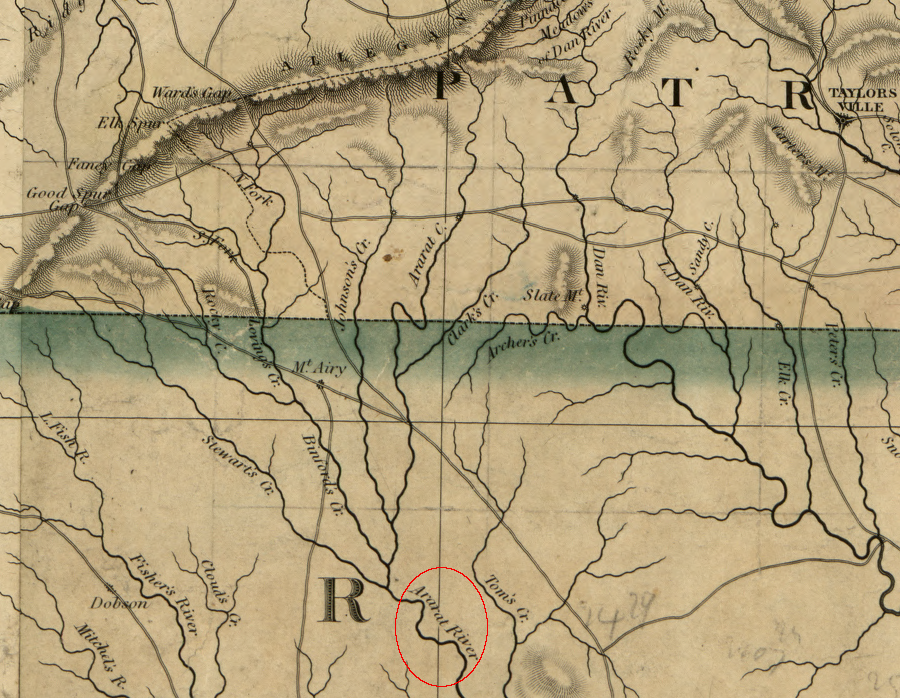

the Ararat River in Patrick County is the only Virginia watershed east of the Blue Ridge that is not in the Chesapeake Bay or Albemarle Sound watersheds (the Ararat River part of the flows into the Yadkin River upstream of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and the Yadkin River then flows into the Pee Dee River)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents (1859)

Source: Library of Congress, The adventures of Junior Raindrop (1948)