Cascades (Giles County)

To make a waterfall, Mother Nature and Father Time need three ingredients:

Waterfalls most often visited by tourists are concentrated in the Blue Ridge and along the Fall Line, though there are waterfalls of various height across the state. An early writer in 1676 noted that the waterfalls on the Fall Line were dependent upon the rivers flowing east from the Blue Ridge:1

Cascades (Giles County)

Virginia has plenty of water for waterfalls. On the average, over 40 inches of rain falls each year across the state. Some is absorbed by vegetation and evaporates (actually, "transpires") from leaves and needles. The cooling effect of evapotranspiration is what keeps temperatures from reaching above 100 degrees on most summer days in Virginia. The evaporating spray at waterfalls creates the same cooling effect.2

Rainfall that is transpired by plants or evaporates from a hot parking lot's pavement will not reach a waterfall. Normally a Virginia waterfall is less impressive in August than in April because evaporation and transpiration reduces streamflow, but waterfalls can reach impressive peaks after a summer thunderstorm or hurricane.

The presence or absence of topographic relief determines where Virginia waterfalls are located. The resistance of the rock determines the type of waterfall.

Tidewater east of Interstate 95 is the flattest portion of the state, but there are still a few bluffs over 20 feet high. Fones Cliff along the Rappahannock River is 100' high, while Horse Head Cliffs at Westmoreland State Park on the Potomac River is up to 150' high. Even on the Eastern Shore north of Kiptopeke State Park, bluffs provide enough of a drop in elevation to create a waterfall wherever a stream is present and sediments are consolidated enough to resist erosion.

The bedrock of the Coastal Plain consists of weakly-consolidated sediments. Streams crossing the bluffs quickly etch a valley into the soft rock, rather than form an impressive waterfall. The soft formations in Tidewater Virginia form gullies rather than waterfalls, wherever streams cut through clay and sand sediments.

At the Fall Line, however, all three ingredients are present for making waterfalls where Virginia rivers drop 50-100 feet in elevation from the Piedmont to sea level. Unlike the sediments on the Coastal Plain, the bedrock of the Piedmont is hard, metamorphic rock which is resistant to erosion.

The eastern edge of the Fall Line in Virginia is the eastern edge of waterfalls where rivers reach sea level. Those waterfalls blocked ships from sailing further upstream, resulting in a series of Fall Line cities stretching from Baltimore to Augusta, Georgia.

The waterfalls are created when rivers flowing across the hard metamorphic bedrock of the Piedmont physiographic province reach the soft sediments of the Coastal Plain. East of the point where rivers reach sea level, river bottoms are muddy sediments on top of the buried hard metamorphic rock. By the time the James River reaches Hampton Roads, the layers of sediments underneath the river bottoms are thousands of feet deep and 145 million years old.

West of the point where rivers reach sea level, river bottoms are hard metamorphic rock. The rivers are eroding into that bedrock, cutting a channel. The western edge of the Fall Line could be defined as the location where the gradient of that channel becomes significantly steeper.

Rivers flowing from the Blue Ridge to the western edge of the Fall Line typically drop about 1-2' per mile as they flow east. Rapids and waterfalls develop where that gradient steepens significantly, as much as 14' per mile in the James River at Richmond.3

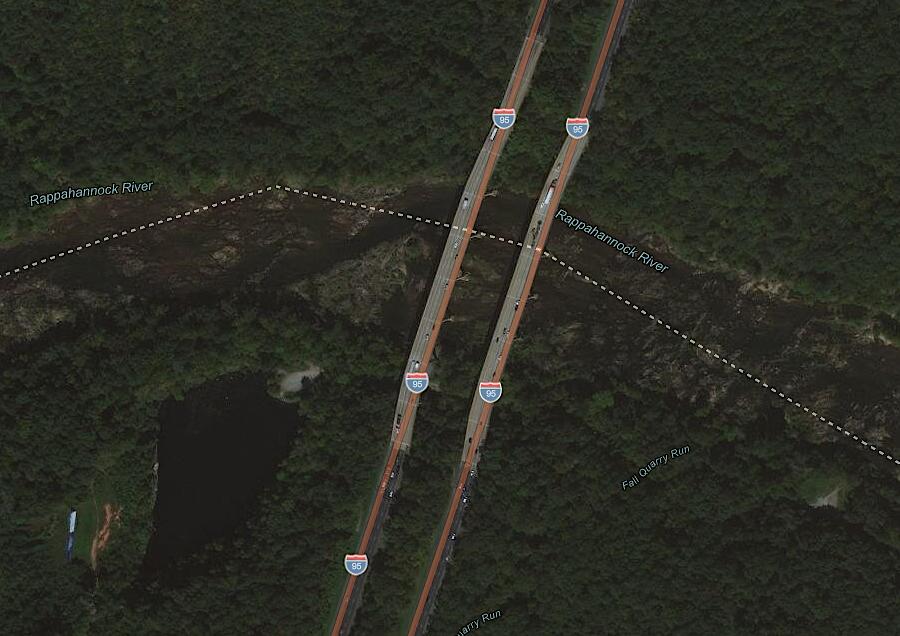

For many Virginia rivers, the change in gradient creates a distinct zone of turbulent flow that continues until the water reaches sea level. The rapids in the Rappahannock River and Janes River visible from I-95 mark a portion of the Fall Line.

the waterfalls viewed most often in Virginia are Fall Line rapids along I-95

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Great Falls, on the Potomac River

The James River has eroded into the bedrock from the I-95 bridge upstream to the Huguenot Bridge, so the James River crosses the Fall Line in a series of rapids rather than in one giant Niagara-like waterfall. The Potomac River has etched into the bedrock from the Teddy Roosevelt Bridge in the District of Columbia, carving a gorge upstream. The rock at the upstream end of the gorge is particularly resistant, so nearly all of the elevation drop occurs at Great Falls now. (Great Falls is 11 miles upstream from the contact between Piedmont and Coastal Plain, so the creation of the gorge demonstrates the power of the Potomac River to erode even the metamorphosed bedrock.)

Not all Virginia rivers cross the Fall Line, and not all riffles in a river are high enough to qualify as a "waterfall." Boaters on the downstream section of the Shenandoah River are well aware of the tiny limestone ledges that require some skill in "reading the water" to avoid turning over a canoe or running a bass boat aground. Bull Falls near Harpers Ferry is the most significant ledge on the Shenandoah, but the Shenandoah enters the Potomac River far upstream of the Fall Line at Great Falls.

limestone ledges in Cedar Creek under Natural Bridge (Rockbridge County)

The New River, the Big Sandy, the Holston, the Clinch, and the Powell as well as other streams on the western side of the Eastern Continental Divide flow to the Mississippi River, never coming near the Fall Line in Eastern Virginia. There are waterfalls along those rivers too. The New River flows through McCoy Falls (called "Big Falls" in the DeLorme Atlas and Gazetteer) where it cuts through Walker/Sinking Creek Mountain downstream from Radford. Further upstream, where the New River drops over a small ledge, a textile factory was built to take advantage of the waterpower. That waterfall stimulated development of the town of Fries.

Virginia's tallest waterfalls are in the Blue Ridge, because there is plenty of water, hard bedrock - and the elevation differences are greatest there. There is nearly 2,000' of potential topographic relief between the top of the mountains and the base of the Blue Ridge in the valley floor to the west, or the Piedmont to the east.

The smaller streams in the mountains can drop spectacular distances, creating impressive scenic attractions in Shenandoah National Park and along the Blue Ridge Parkway. In the Blue Ridge, streams have not finished the physical process of eroding the hard volcanic or granitic bedrock and levelling the mountains into a flat plain.

Native Americans recognized the distinctive character of places in the Blue Ridge where they could hear as well as see waterfalls. Models on where to find archeological sites that were based on locations of food to hunt/gather/grow, water to drink, and rock to process into tools are now incorporating locations where infrasound from waterfalls can be sensed.

Bells and drums generate infrasound as well as audible sound, and percussion was a common element in the music encountered by colonists in the Contact Period. Waterfalls may have been visited just for beauty and recreation, and may also have been viewed as offering a special opportunity for spiritual connections valued in preparation for rituals. Canyons with waterfalls also may have concentrated infrasound and audible sound generated by thunderstorms.

Archeologists are discovering pottery fragments near Blue Ridge waterfalls at locations even before waterfalls could be seen, as people followed stream valleys upwards. Where infrasound was first sensed:4

the lowest of five cascades over knickpoints at Crabtree Falls

Source: Crabtree Falls (by Jim Liestman)

Crabtree Falls is often mentioned as Virginia's highest waterfall. The waterfall is created as Crabtree Creek descends 1,000 feet in the Blue Ridge of Nelson County before flowing into the Tye River.

The Virginia Tourism Corporation describes Crabtree Falls as:5

The adjectives are relevant. Technically, Crabtree Falls is a cascade. There are five major drops as the water flows over one billion year old granite bedrock, which was emplaced during the Grenville Orogeny when the supercontinent Rodinia formed.

The Blue Ridge at the site of the cascades is being rejuvenated, uplifted by perhaps compressional forces in the tectonic plate. That uplift has disrupted the stream channel. Instead of reflecting a "mature" pattern with a steep headwaters segment and then a gradual bending towards a more-gentle slope, the "hypsometric curve" reflects a disequilibrium landscape with knickpoints where water drops vertically.6

Falls of the Little River (Floyd County) and Dismal Falls (Giles County)

artificial waterfall: dam at Gatewood Reservoir (Pulaski County)