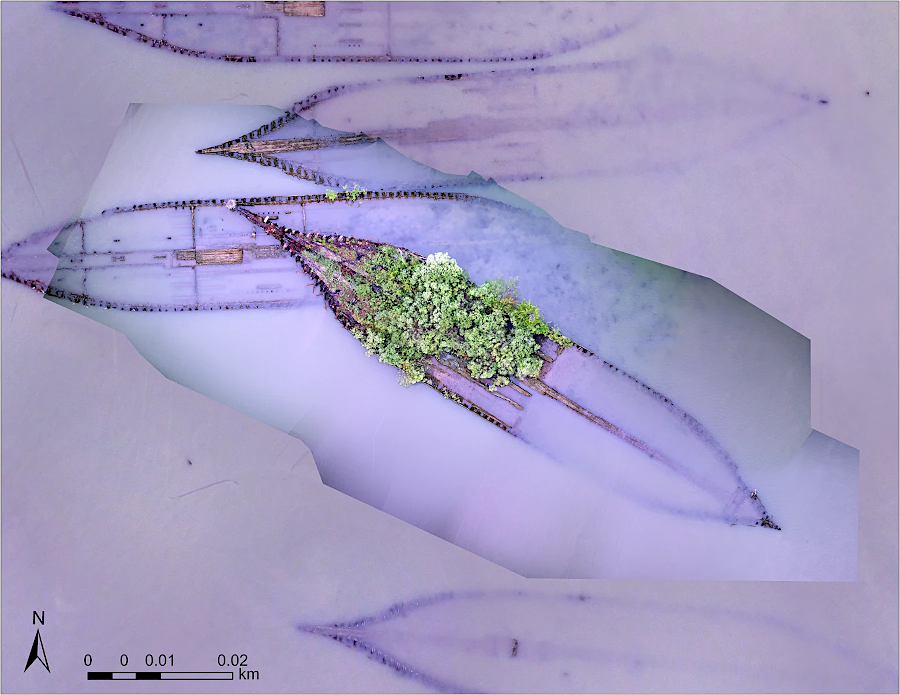

a site on the North Landing River next to the Chesapeake/Virginia Beach border has become a boat graveyard

Source: National Park Service, Paddle to Sunken Ships at Dutch Gap Conservation Area

Sunken boats have accumulated in Virginia waters for centuries. Spanish ships started sinking off the coast of North America in the 1500's. Since then, certain areas have become natural boat graveyards, while other areas have been chosen on purpose as a place for abandonment.

In 1781 at Yorktown, the British navy scuttled the remainder of its fleet, the boats not already sunk by French and American artillery fire, before surrendering. Nearly 40 ships ended up on the bottom on the York River, including the HMS Charon.1

There are boat graveyards on the Potomac and James rivers that are now attractions for recreational boaters. At Dutch Gap Conservation Area on the James River, canoeists and kayakers can explore the remains of several wooden barges that once hauled sand and gravel, Decaying slowly next to them on the shoreline is an old metal tugboat. The National Park Service advertises the Lagoon Water Trail as an attraction for boaters on the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail.2

a site on the North Landing River next to the Chesapeake/Virginia Beach border has become a boat graveyard

Source: National Park Service, Paddle to Sunken Ships at Dutch Gap Conservation Area

On the Potomac River, boaters can see the "Ghost Fleet of the Potomac" at Mallows Bay. Submerged boats overgrown with vegetation are located within Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary, established by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2019.

The graveyard started with construction of 734 new ships ordered in 1917 by the United States Shipping Board as the United States entered World War I, in anticipation of an urgent need to transport soldiers and supplies to Europe. Eventually 87 separate shipyards received contracts for building wooden ships, 240-300 feet in length, based on a standard design. When the war ended on November 11, 1918, only 134 had been completed and 98 of the ships had been delivered; none had crossed the Atlantic Ocean to deliver cargo for the war effort.

After World War I there was no demand for poorly-built wooden ships fueled by coal; the cargo business desired steel ships fueled by diesel. In 1920, the US Navy stored 285 of the unneeded ships in the James River. They were anchored next to Camp Eustis, which is now part of Joint Base Langley-Eustis.

In 1922 an Alexandria company, Western Marine & Salvage Company, purchased 233 of the inactive and incomplete wooden ships in order to salvage the metal from them. The company was authorized to hauul the hulls to a mooring area on the Potomac adjacent to Widewater in Stafford County. The company towed a few ships to Alexandria where machinery would be removed for scrap.

The stripped hulls were towed back to Widewater and burned so nails and other remaining metal could be stripped and recycled. The plan was for the burned hulks to be pushed into marshland on the Stafford County shoreline, and to use dredge spoils from the river channel to cover them.

Watermen objected strenuously that the shad and herring fishery would be damaged. There were 123 hulls stored at Widewater, with nearly 80 more scheduled to be moved, when Western Marine & Salvage Company chose to relocate. It bought land adjacent to Mallows Bay in Charles County, Maryland and towed all the boats there. The company still hauled boats, a few at a time, to Alexandria to strip off the major metal parts. The wooden remainders were towed back to Mallows Bay and burned.

the remains of the "Benzonia" now support vegetation at Mallows Bay

Source: Scientific Data, Mapping the "Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay," Maryland with drone-based remote sensing

Western Marine & Salvage Company ultimately moved 169 ships to Mallows Bay, on the Maryland shoreline. Not all ships had been processed and burned there before salvage efforts stopped during the Great Depression; the company went into bankruptcy in March of 1931.

over 100 wooden steamships were burned at Mallows Bay

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary

Local residents took the opportunity to recover metal. Some also used the ships for floating brothels and making moonshine whisky. In 1942-44, during World War II, scrap recovery was performed by the government-organized Metals Reserve Company.

Source: The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered, The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay

After the war a local utility, PEPCO, secretly purchased the adjacent land in Charles County, Maryland. It lobbied to have the derelict hulls removed, but local opponents to construction of an electricity generating plant blocked the utility's plans. The Federal government determined that the Ghost Fleet could remain in place. Maryland funded marine archeology that documented the ship graveyard also includes a derelict menhaden boat, car ferry, workboats, barges, and even a possible Revolutionary War longboat.

Only one wooden hull is still above water, while vegetation grows on many of the hulks. Plants and aquatic creatures have taken advantage of the shade and structure that the derelict ships provide.

Source: NOAA Sanctuaries, Explore the Blue: 360° Mallows Bay Ghost Fleet

Today the site is a floating forest. Designation of Mallows Bay as a National Marine Sanctuary happened finally in 2019. That designation was delayed by opposition from watermen who feared Federal restrictions in their harvest seasons and operations. Many historians, conservationists, and boaters now consider the wrecks to be a "mistake turned ecological treasure." As described by the president of the Chesapeake Conservancy:3

the Ghost Fleet at Mallows Bay ended up as a tourist attraction

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Mallows Bay - NOAA Marine Sanctuary Potomac River Nanmejoy (MD) 2023 (by Ron Cogswell); Aerial footage of Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary

Another ghost fleet is located in the Nansemond River, within the boundaries of the City of Suffolk. The Virginia Department of Historic Resources has designated the Nansemond Ghost Fleet as an historic site, 44SK0631.

The cluster of wooden vessels was discovered in 2017 near the Main Street Bridge. A marine archeology program has found 13 vessels of various types:4

the remains of 13 abandoned vessels in the Nansemond Ghost Fleet are now a historic site

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), The Nansemond Ghost Fleet (p.84 and Figure 25)

After World War II, another excess of ships ended up being mothballed. They were stored at the site where the wooden ships had been anchored after World War I. Those ships were designated as the James River Reserve Fleet. It is now managed by the Maritime Administration (MARAD), which is part of the US Department of Transportation:5

The Maritime Administration is responsible for disposal of Federal ships that are at least 1,500 gross tons and no longer useful for defense or aid missions. Some are sunk in the SINKEX program, used at-sea live-fire training exercises by the US Navy. Because the salvage value of dismantling/recycling ships is lower than the cost in US shipyards that must meet worker safety and environmental regulations, the Maritime Administration typically must pay shipyards to dispose of old ships.6

The James River Reserve Fleet (JRRF), the first of eight National Defense Reserve Fleets, is one of three fleets that is still active. It includes decommissioned U.S. Navy ships and obsolete commercial vessels:7

part of the James River Reserve Fleet in 1990

Source: Wikipedia, James River

barges that one hauled sand and gravel now form an underwater graveyard at Dutch Gap on the James River

Source: RESRI, ArcGIS Online