Naming and Numbering Virginia Roads

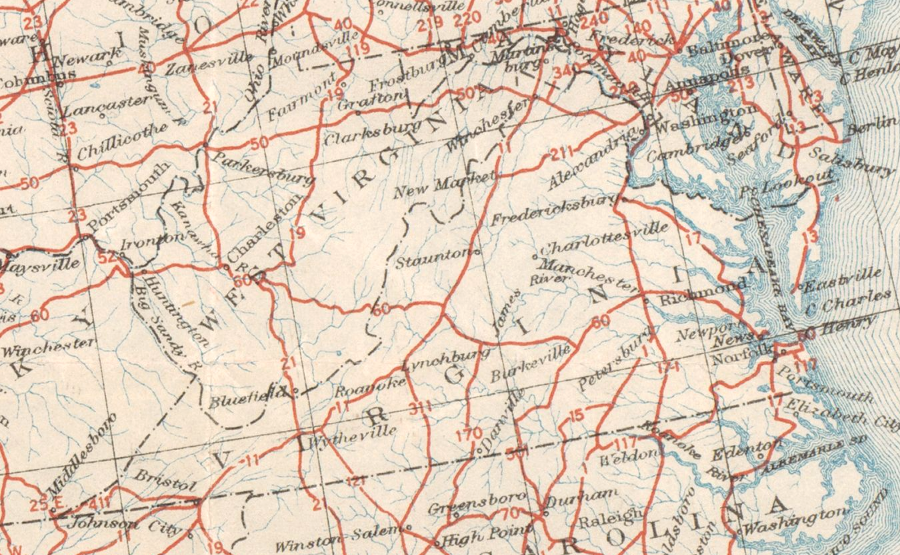

roads eligible for Federal funding were numbered initially by the Joint Board on Interstate Highways in 1925

Source: University of North Texas Libraries, United States system of highways: adopted for uniform marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials, November 11, 1926

Colonists in Virginia marked their roads by cutting marks in trees, rather than installing signs. To get from Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley, a traveler followed an old Native American path which the English improved to Three Chopt Road. The marks on the trees were supplemented with milestones, numbered west to east, by the early 1740's.

A traveler from Switzerland in 1702 reported:1

- We met a man on horseback (it is a strange sight to see anyone traveling on foot) whom we asked about the way. For the guidance of those not knowing the way it is only necessary to watch the signs that are found on trees along the great high road. Every year white places are cut into the trees with hatchets, by the removal of the bark. There are so many ways that otherwise one could easily go astray. There are many paths that lead to plantations, others have been made by the cattle or the game.

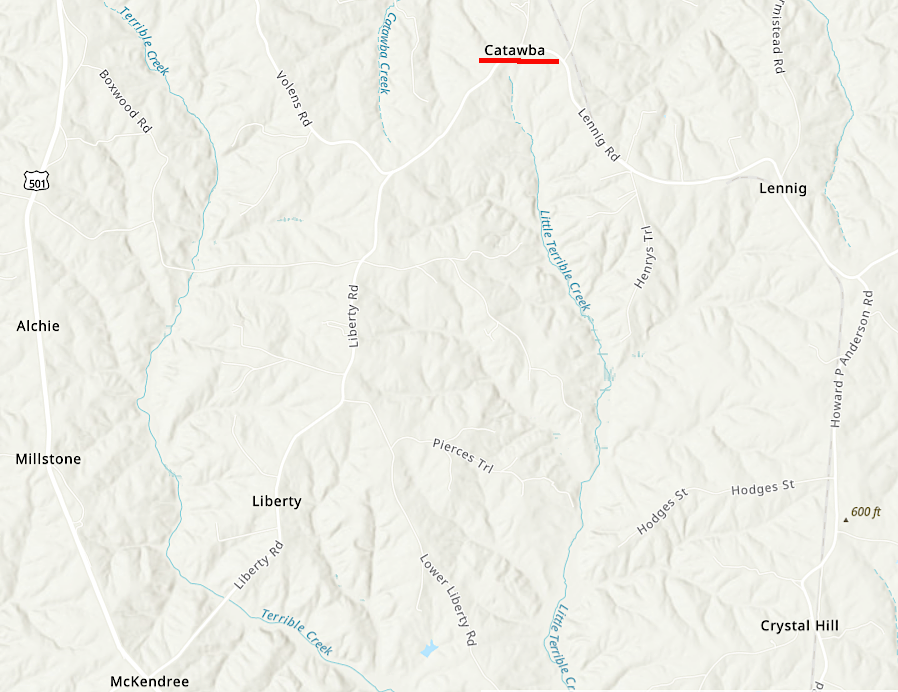

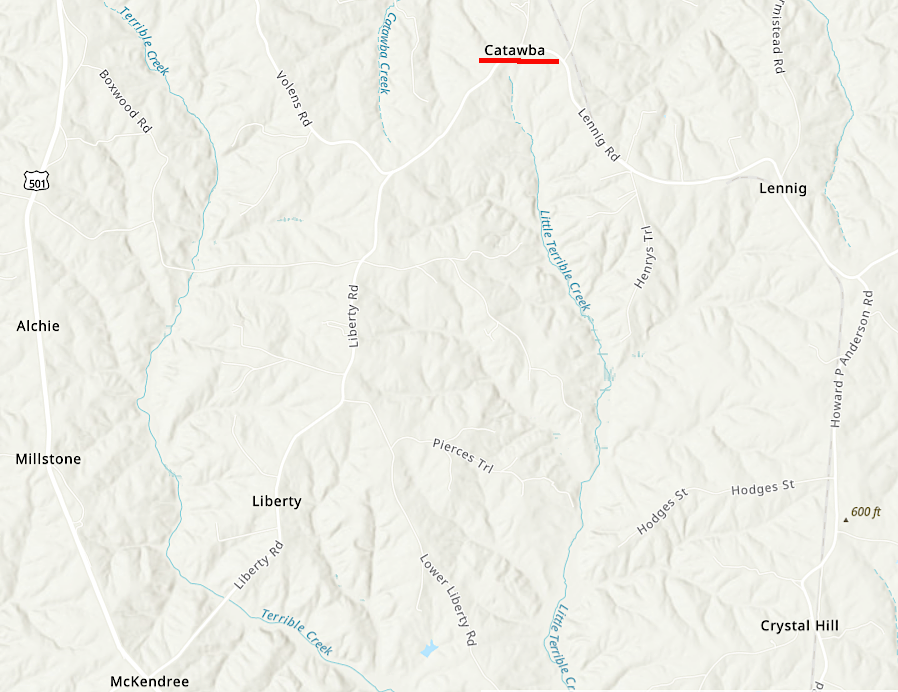

One of the oldest highway signs in Virginia is in the community of Crystal Hill in Halifax County. When the Virginia Department of Transportation began widening Route 626 (Howard P. Anderson Road) in 2018, local residents reported that a slab of rock partially buried under the roots of the tree and broken into pieces was a historic road sign. When George Washington passed through the area in 1791, the words chiseled into the rock were stil readable:2

- The Right/ To Coles Fery/ 11 Miles/ The Left to/ Barksdales Store/ 6 Ms.

the ancient road sign to "Barksdales Store" leads to what is now known as Catawba (Halifax County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

For centuries, Virginians used names rather than official numbers to refer to roads. Prior to the American Revolution, the major north-south route along the Fall Line was called the King's Highway. Developers of turnpikes chose their name, such as the Little River Turnpike. Residents often referred to the local road by the name of the town to which it connected. People living in Fauquier and Prince William County talked about the turnpike leading east to the Potomac River as the Alexandria road, while Alexandria residents called it the Warrenton Turnpike.

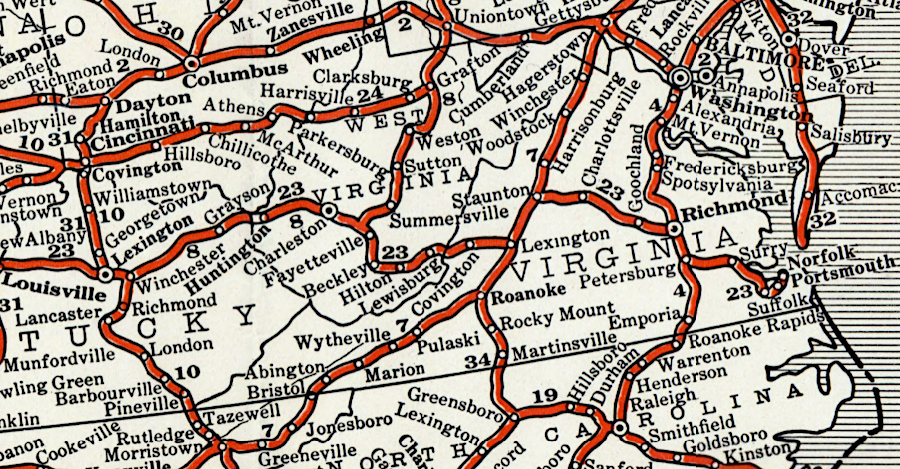

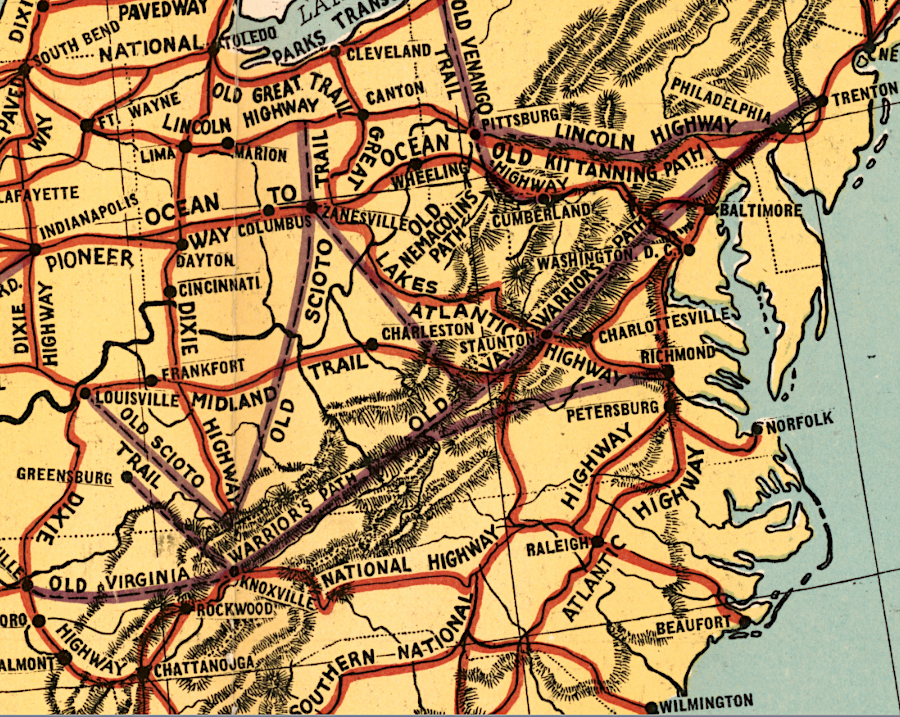

After development of the automobile, private organizations such as the Virginia Good Road Association agitated for government funding to pave roads and get various states "out of the mud." Communities partnered with trail sponsors to label roads in order to draw tourists to a particular area. Some trail sponsor organizations convinced towns and cities to contribute funds in order to market a named route, which reflected geographic distinctions. The Lincoln Highway Association routed the Lincoln Highway north of the Ohio River through Illinois, while different routes labeled "Dixie Highway" led to destinations in the South.

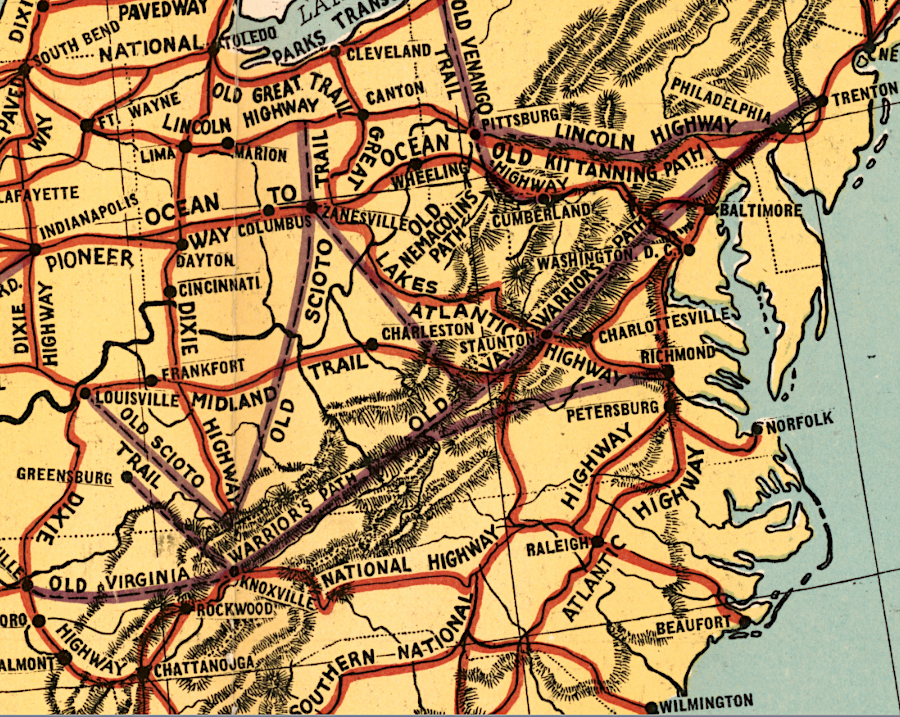

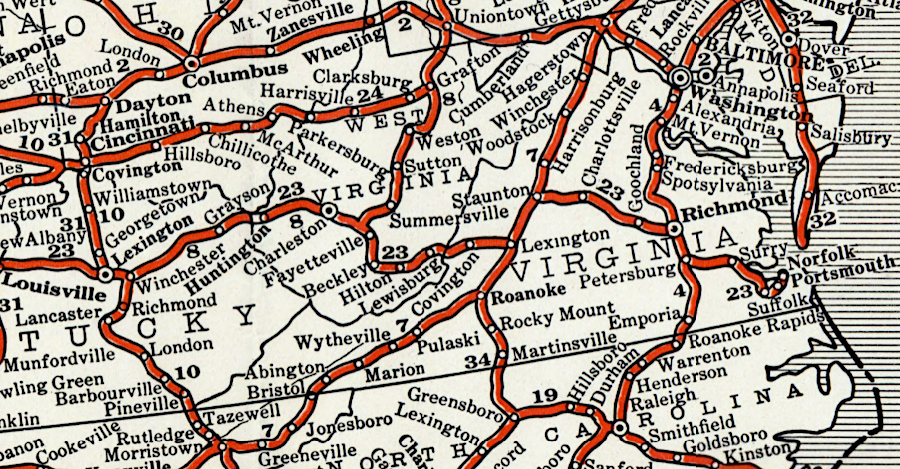

In 1914, the National Highways Association proposed a 50,000-mile network of 37 national highways. Five national roads would pass through Virginia - Atlantic (Number 4), Appalachian (Number 7), Indiana-Atlantic (Number 23), Ontario-Chesapeake (Number 32), and Roanoke-Greensboro (Number 34).

of the 37 national highways proposed in 1914, five were in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Fifty Thousand Miles of National Highways Proposed by the National Highways Association (1914)

Local communities and trail organizations competed as much as cooperated with each other as rivals. By the 1920's, it was common to have multiple trail markers on the same route. Sometimes less-than-respectable trail sponsors gave the same highway name to different roads, after getting competing communities to endorse and provide funding based on marketing promises.

By 1925, confused drivers could follow 250 marked "trails" identified by various organizations. An organization with a perspective broader than local tourism advertising was needed to coordinate and construct a cost-effective network of paved roads linking major population centers.

paved roads built in the early 1900's were named before they were numbered

Source: Library of Congress, The comprehensive series, historical-geographical maps of the United States: Trails and Highways (1919)

Federal leadership to standardize the highway system came slowly. In 1893, Congress established the U.S. Office of Road Inquiry in the Department of Agriculture in 1893. That office was renamed the Office of Public Roads in 1905, then the Bureau of Public Roads in 1915.

In 1906, the General Assembly created the State Highway Commission. The legislature also authorized the use of the labor from convicts for road construction and maintenance. The first appropriate from the state treasury for a road project was approved in 1908. Registration and licensing of motor vehicles was required starting in 1910. That same year the General Assembly established the state's first speed limits - 8 miles/hour in towns, and 20 miles/hour in open country.

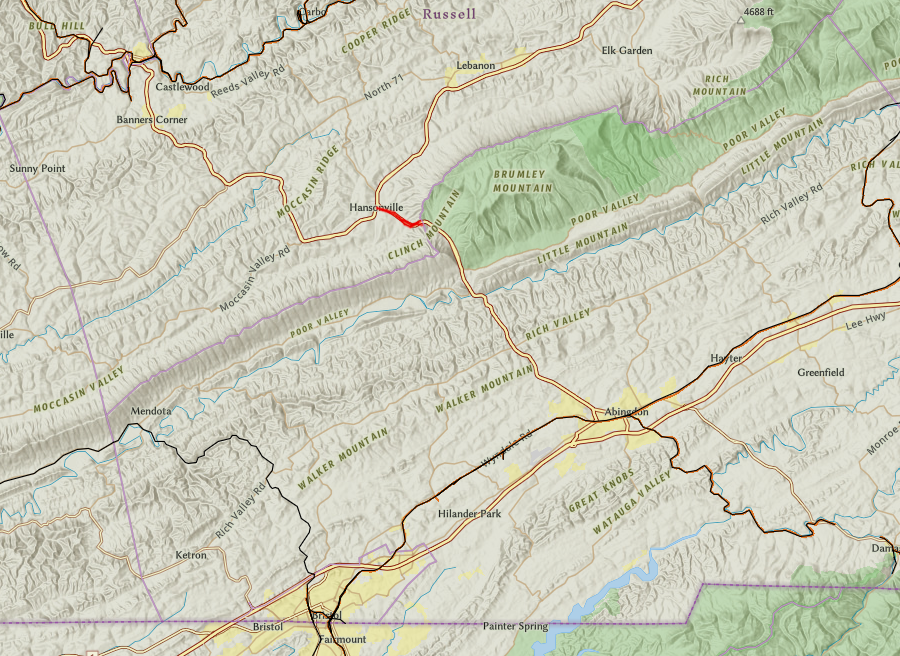

The US Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act in 1916 and began to provide Federal funding to establish a nationwide highway system. In 1918, Virginia's General Assembly committed to provide funding for a statewide highway system totaling 4,002 miles. The shift in government responsibility for the transportation network, away from local jurisdictions to Federal/state organizations, led to standardization of the "wayfinding" system with consistent identification of routes between major cities.

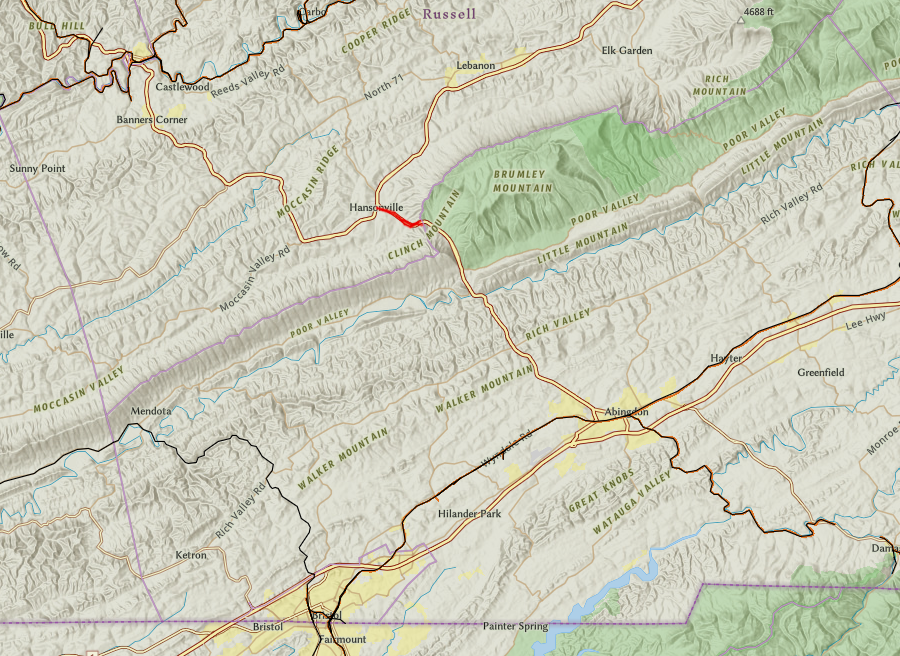

what is now Route 19, between Hansonville and Moccasin Gap at the Russell County boundary, was the first stretch of road improved with Federal funding

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Federal government's Bureau of Public Roads worked with state officials, who organized as the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). Federal/state officials negotiated a new road designation system which was based on route numbers rather than names, eliminating the potential of a major highway such as Route 66 changing its number when it crosses a state line.3

The modern highway network is based on consistent route numbers assigned by government agencies rather than private organizations. The naming of highways, bridges, and other transportation facilities for tourism and memorialization of people/groups still continues. The emergence of multiple craft breweries, wineries, cideries, and distilleries along Route 151 in Nelson County led to tourism officials designating it as the Nelson 151 Trail, incorporating the route number in the state's Secondary System of highways. In addition, visitors still refer to Route 151 informally as "alcohol alley."4

marketing for a major highway in Nelson County includes the official number for Route 151

Source: Virginia Tourist Authority, Nelson 151 Craft Beverage Trail

The Bureau of Public Roads was still a part of the US Department of Agriculture when the nationwide road numbering system for US highways was adopted in 1925. That reflected the initial priority to facilitate farm-to-market commerce; the US Congress did not authorize the Federal Department of Transportation until 1966.

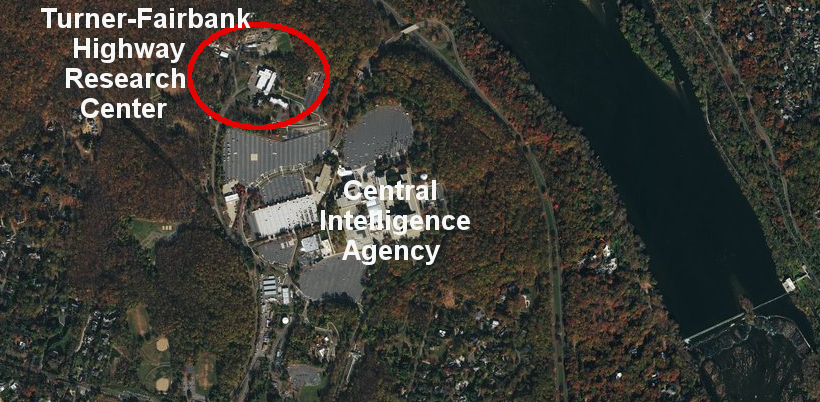

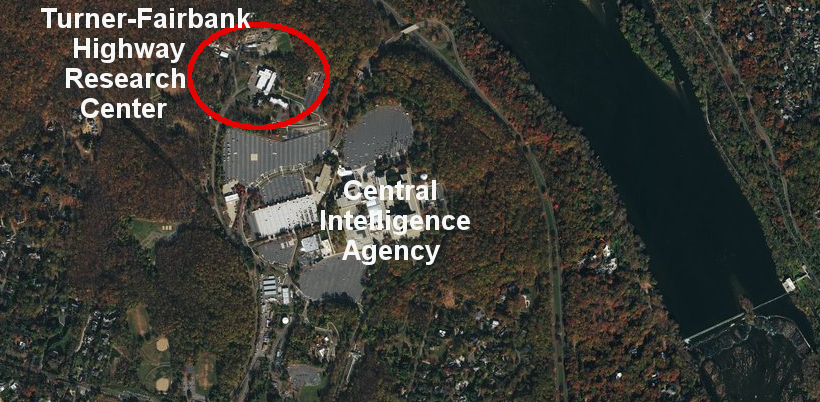

During the Great Depression, the Bureau of Public Roads became part of the Federal Works Agency and was renamed the Public Roads Administration in 1939. Ten years later, the agency was transferred to the US Department of Commerce and the name reverted back to Bureau of Public Roads. The exit to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters, on the George Washington Memorial Parkway, was marked for many years by only a sign for the Langley Research Station of the Bureau of Public Roads. Today that facility is called the Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center, and the highway sign directs travelers to the Central Intelligence Agency.

The Bureau of Public Roads had consistent leadership even as it changed names. Thomas H. MacDonald remained the head of the organization from 1919-1953, and that continuity facilitated building trust with the state highway agencies. The last agency name was Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). It was applied in 1966, when the agency was incorporated into the new US Department of Transportation.5

the Bureau of Public Roads facility next to the Central Intelligence Agency is called the Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center now

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The slow increase in the role of the Federal government was linked to the slow increase in Federal funding for road construction. Under the Post Road Act of 1912, the Office of Public Roads built demonstration roads in Virginia and several other states.

Virginia Highway Commissioner George P. Coleman helped to draft the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. It allocated Federal funds for 50% of the cost to pave rural post roads, linking back to the authority granted to the Federal government in Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution "To establish Post Offices and post Roads." Since the US mail was transported by train between major cities, the 1916 law did not provide funding to pave the main thoroughfares because they were not "post roads."

In 1918, supporters of Federal funding for long-distance roads organized a Joint Highway Congress of the Highway Industries Association and the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). It debated whether Federal aid should be focused on building a limited number of major national highways to be constructed and managed by the Federal government, or distributed to the states for broader use with all highways constructed and managed by state agencies.

State officials lost the debate. The Joint Highway Congress proposed a national highways system to be constructed by the Federal government, passing resolutions that included:6

- That a federal highways commission be created to promote and guide this powerful economic development of both highways and highways traffic and establish a national highways system...

- That all governmental activities with respect to highways be administered by the federal highways commission.

Meeting separately, the Highway Industries Association proposed Federal funding for a national arterial highway system of 50,000 miles. The Federal government would build and manage 5 east-west routes and 10 north-south routes. In that scenario, a Federal Highways Commission - not the trails organizations, and not the states - would have full responsibility to determine how to identify the 15 most important highways in the United States for "through traffic" that linked major population centers.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 did not create a Federal Highways Commission to construct and control a 50,000 mile national road network. Instead, it expanded eligibility for Federal funding so states could improve roads that could potentially be used by the postal service, as well as roads actually used for transport of the mail. Improving roads included upgrades such as putting down a gravel surface, installing drainage ditches, and straightening curves as well as paving.

Federal funding could be applied to just 7% of roads within a state, particularly the 3% of roads designated as a primary road system. Federal aid to the states gave the Department of Agriculture, through the Bureau of Public Roads, the power to designate a system of arterial roads that would link up at state boundaries. Key Senators apparently calculated that a system including 7% of existing roads was the lowest fraction that would provide each state at least one road going east-west and another road going north-south across the state.7

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 accommodated state concerns by providing Federal aid to states, ending the proposal for a Federal highway department building roads independently. State governments would be responsible for constructing the 7% of roads that could be financed with Federal funds, as well as the other 93% of roads financed with local/state funds. In 1922, the General Assembly defined boundaries for eight highway districts and required funding be allocated equally among them.

the Washington-Richmond Highway through Chopawamsic Swamp was paved in 1920, and renamed Route 1 in 1926

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Facebook post (December 4, 2020)

Creation of the "Seven Percent Road System" meant that the states did not get flexibility to spend Federal funds on low-priority farm-to-market roads. Identifying, improving, and naming/numbering the roads in the Federally-funded arterial network would become a joint effort of Federal and state officials. The compromise, mixing Federal and state responsibilities, answered the questions raised by Rep. John Robsion of Kentucky during the debate:8

- Do we want to create a "tourist" system of roads or strengthen and build up our present "farm-to-market" system? Do we want to destroy the "producers-to-consumers" system and install a "joy-rider" system?

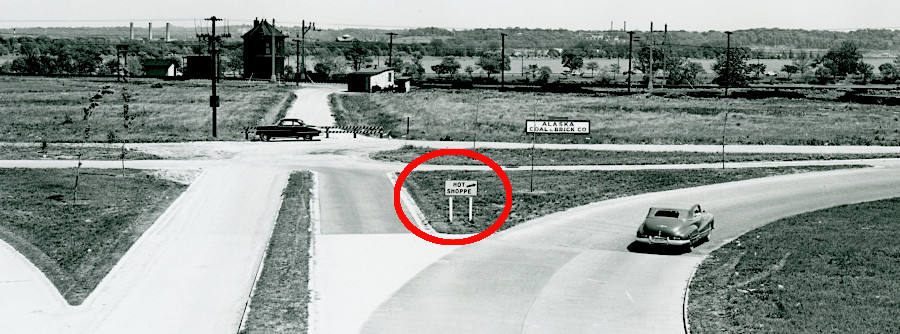

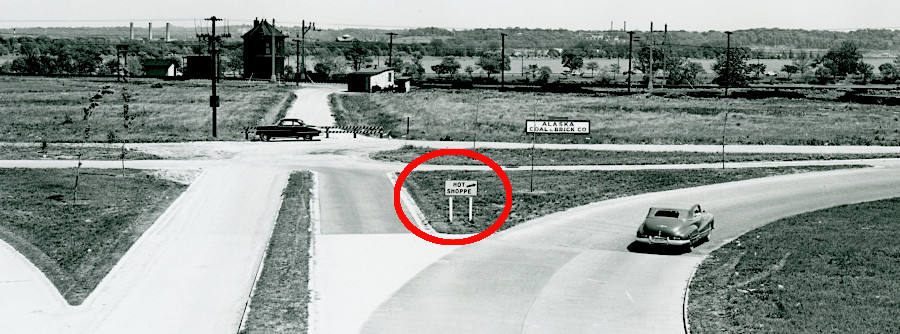

the sign to the Hot Shoppes at Fairlington traffic circle was very basic

Source: National Archives, Traffic Signs in Virginia (May 1952) and Shirley Memorial Highway (July 1, 1947)

In 1924, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) proposed that the Secretary of Agriculture name a joint commission of officials from the Bureau of Public Roads and the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). The group would be tasked with responsibility for identifying a network of highways used for interstate travel, and adopting standards for directional and warning signs.

The Joint Board on Interstate Highways held meetings in different regions across the country. State officials were invited to testify, while trail organizations had to share their ideas and concerns in informal meetings.

In 1925, the Joint Board decided that green lights would mean "go," yellow mean "caution," and red mean "stop." The group chose standard shapes, as well as colors, for highway signs. Originally it wanted the background on the octagonal STOP sign to be red, but could not find a durable paint in that color. The standard for STOP signs was black on yellow until new paint and enamel technology evolved. The revision to today's white on red standard was adopted by the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) in 1955.

The symbol chosen to designate US highways was a shield with a route number inside. After extensive debate, it was agreed that the state name could be included as well. Southern states insisted on state names since states would be paying for signs. One participant later wrote:9

- Hamilton and Jefferson saved the Constitution by locating the National Capital in the South. We saved the United States Numbered System by recognizing the name of each State on every road shield erected on roads forming a part of the United States road system in that State.

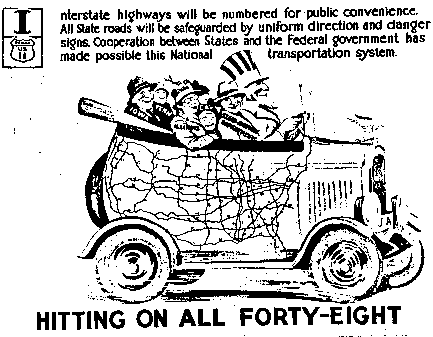

the Joint Board on Interstate Highways decided to assign numbers, not names, to the national highway network

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Origins of the Interstate System

The officials decided that the road network should have uniform style of marker and roads should be numbered, not named. Though the Lincoln Highway Association and some other trails organizations were respected, other groups were perceived as parasites extracting money from communities without providing any return on the marketing investment. Such organizations were described by one newspaper as:10

- blood-suckers who have sat in their swivel chairs and milked the public for funds to keep their swivels greased.

One person joked that the shift from named highways to numbered highways should be extended. When describing presidents, George Washington should be known as President Number 1, and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans should be renamed Ocean Number 1 and Ocean Number 2.11

Identifying a 75,884 mile primary road network was especially challenging. The final recommendations, with 32 primary routes, totaled 2.6% of the 2,862,197 miles of public roads that had been certified by the states.

Virginia certified that it had 53,338 miles of public roads in 1925. The state proposed 2,614 miles (4.4% of certified road miles) to be included in the Federal road network, the Joint Board on Interstate Highways selected 660 miles (1.2%) initially, and they settled on 1,543 miles (2.9%).

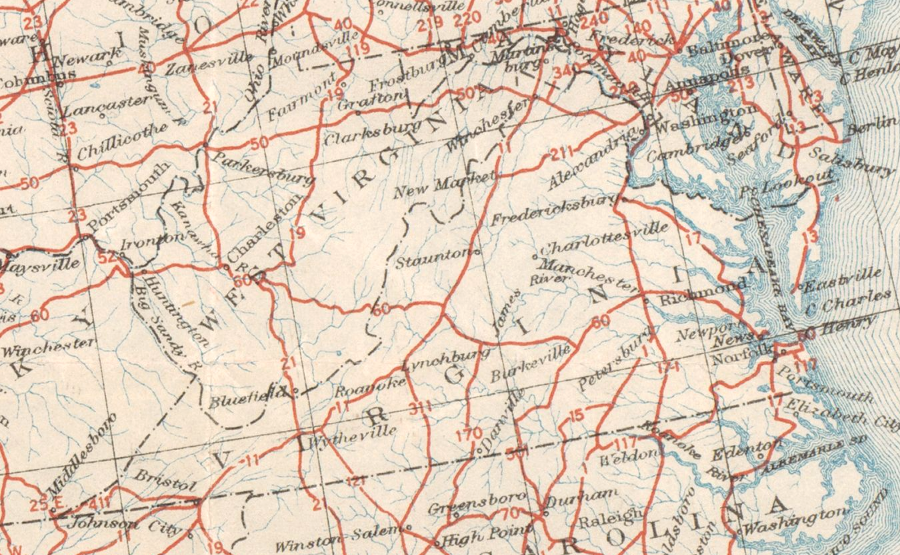

Routes including portions of Virginia were:12

- Route 1 from Fort Kent (Maine) through Alexandria/Fredericksburg/Richmond/Petersburg to Miami (Florida)

- Route 11 from Rouses Point (New York) through Winchester/Staunton/Bristol to New Orleans (Louisiana)

- Route 13 from Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) through Cape Charles to Wilmington (North Carolina)

- Route 15 from Petersburg through Emporia to Wilmington (North Carolina)

- Route 21 from Cleveland (Ohio) through Wytheville to Jacksonville (Florida)

- Route 50 from Annapolis (Maryland) through Winchester to Wadsworth (Nevada)

- Route 52 from Newport News through Richmond/Burkeville/Lynchburg/Lexington/Covington to Fowler (Indiana), Route 170 from Greensboro (North Carolina) through Danville/Lynchburg to Lexington

- Route 211 from New Market to Alexandria

- Route 301 from Fredericksburg through Saluda/Yorktown to Lee Hall

- Route 311 from Roanoke through Martinsville to Aberdeen (North Carolina)

- Route 401 from South Hill through Clarksville to Sanford (North Carolina)

- Route 411 from Bristol to Corbin (Kentucky), Route 501 from Burkeville through Halifax to Durham (North Carolina)

The 7% network was based on recommendations from the Bureau of Public Roads staff. The centroid of the national road system ended up in the same Indiana county as the centroid of the national population. That suggested the proposed road network would link population centers, and was not based on the tourism marketing goals of trails organizations that diverted travelers to isolated areas.

The key individual on the Bureau of Public Roads staff, E. W. James, later recalled a Geographic Information System process which combined data from physical maps rather than overlayed layers in a computer:13

- We first selected from the Post Office Department the only complete uniform set of State maps showing only county outlines. The Post Office used them I think for laying out R.F.D. routes in counties. From the Census Bureau we got population; agricultural produce in dollars; manufacturer's, mineral, and forest products also in dollars and by counties.

- We laid the quantities out for each of the five items, each on a separate set of maps, in each State and in each county of each State. Calling the total State population 100, we determined the population index for each county. This process was repeated for each of the five significant items.

- We then combined the indices for all items by counties in each State giving a total of 500. We then divided the combined county indices by 5, bringing the total index figure back to 100 with a single county index representing the importance of that county in the State as a whole.

- We reduced these county indices first to circles, which were not distinguishable enough, so we adopted squares as emblems of the indices. When these squares, blackened in, were put into their appropriate counties on a clean map, we had a series of emblems through which diagrammatic routes could be laid out.

- Routes through the heaviest emblems were routes through the generally wealthiest and all around most important county areas. Road locations could be made catching obvious local control points along these diagrammatic lines, and you had a selection from best to poorest almost staring you in the face.

The decision to number rather than name the network resulted in Virginia "losing" the transcontinental National Roosevelt Midland Trail. That route had two legs that went from Washington, D.C., and Old Point Comfort, Virginia to Charlottesville, then to San Francisco. The route was promoted as a transcontinental route by Kansas and Colorado towns which were upset that they had been bypassed in the Lincoln Highway route chosen in 1913. The Old Point Comfort-San Francisco route was originally called the Midland Trail.

The attempt to rename that route, after former President Theodore Roosevelt died, conflicted with a similar effort further north. The Theodore Roosevelt International Highway was proposed between Portland, Maine, to Portland, Oregon, with a section through Canada which made it "international." Ultimately US 2 was designated between Houlton, Maine, to Everett, Washington, and memory of a cross-country trail named after Roosevelt faded.

Virginia did gain Route 60. That road was a multiple of 10, so it should have been used from the beginning to designate a transcontinental route in the numbering scheme. However, the committee that designated numbers for highway routes initially assigned Route 60 to a Chicago-Los Angeles road.

Kentucky complained that transcontinental traffic was being routed north of the Ohio River. Kentucky's governor highlighted that his state had no major highway ending in "0." The ultimate solution was to designate Route 60 from Newport News to Springfield (Illinois), and re-number the route from Chicago-Los Angeles as Route 66. After World War II, Route 66 became an iconic symbol of traveling by car thanks to popular song with a "get your kicks on Route sixty-six" lyric and a television show.14

the Chicago-Los Angeles route, made famous in a 1960's TV show, was originally proposed as Route 60

Source: Akron Beacon Journal, Local history: "Route 66" TV stars got their kicks at 1961 All-American Soap Box Derby

Creation of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950's required assigning new route numbers. Transportation officials adopted the existing pattern of using odd numbers (ending in 1.3, 5, 7, 9) to identify north-south routes and even numbers to designate east-west routes. However, the interstates on the eastern side of the United States were given the largest numbers, reversing the pattern for existing major roads. US 1, the highway closest to the Atlantic Ocean, was paralleled by I-95. On the West Coast, US 99 was paralleled by I-5.

Switching the numbering scheme for north-south routes ending in "5" reduced potential confusion when referring to an existing highway and a new interstate near the coasts. For the east-west interstates, the lowest number (I-10) was placed in the south and the highest number (I-90) in the north. There is no I-50 or I-60, because those interstates would run too close to US 50 and US 60.

"Minor" interstate routes are short segments at major cities assigned three numbers, such as I-495. The connection to a major interstate is indicated by the last two numbers of a three-number label for a minor interstate. For example, around Richmond I-295 connects to I-95. The same three numbers for minor interstates are used in different states, along with local names. I-495 in Virginia is the Capital Beltway, while I-495 in New York is the Long Island Expressway.

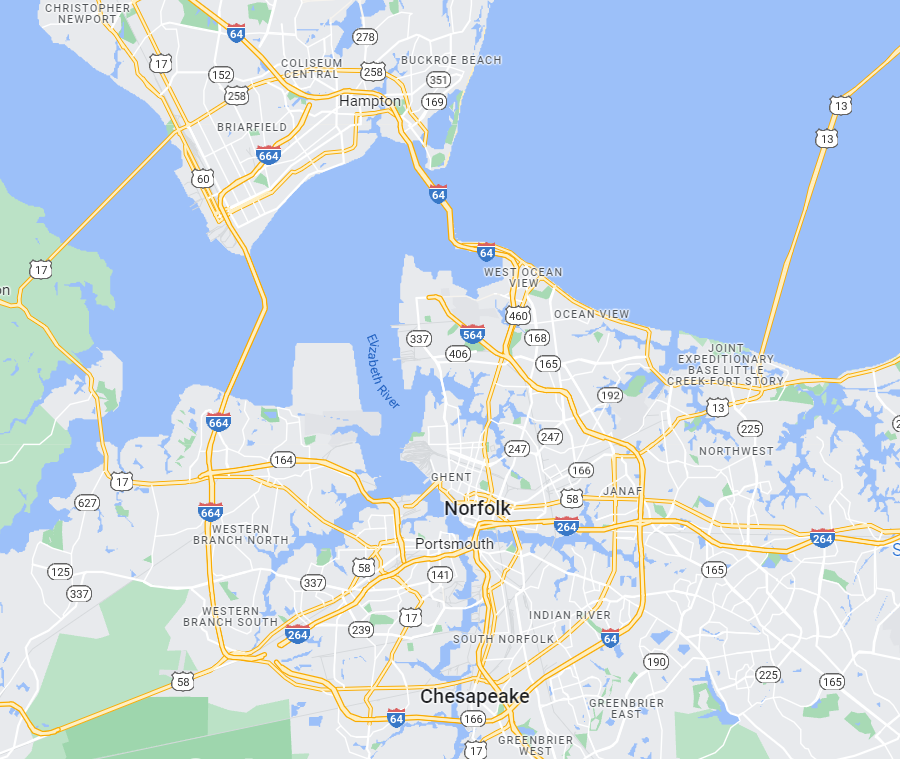

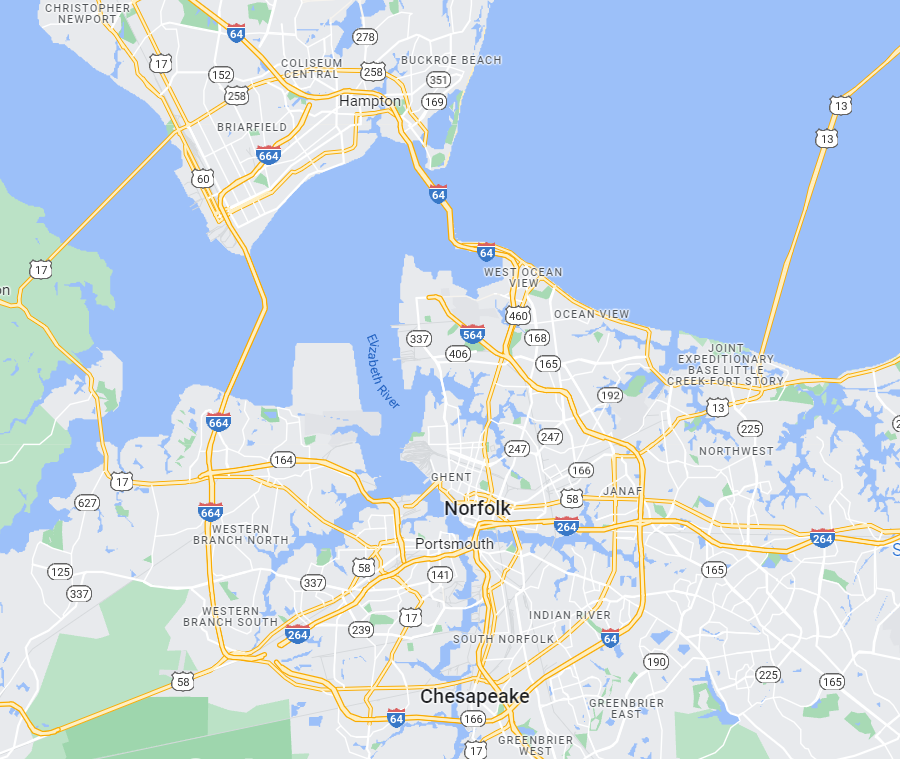

If the first number of a minor interstate is even, then the road will connect at two places to the major interstate and serve as a bypass. I-664 links to I-64 in Newport News to I-64 in Chesapeake.

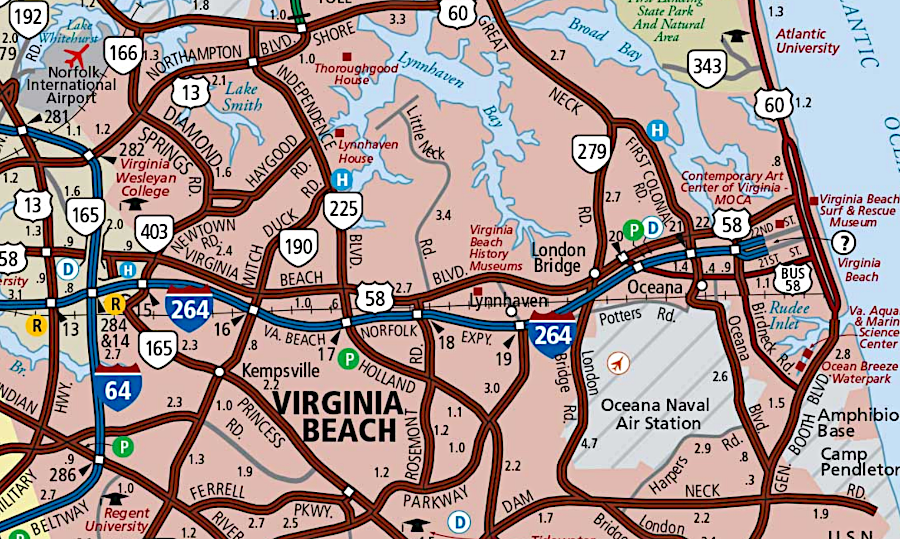

I-664 connects to I-64 at two places, so it uses an even number (6) at the start of its three-number designation

Source: GoogleMaps

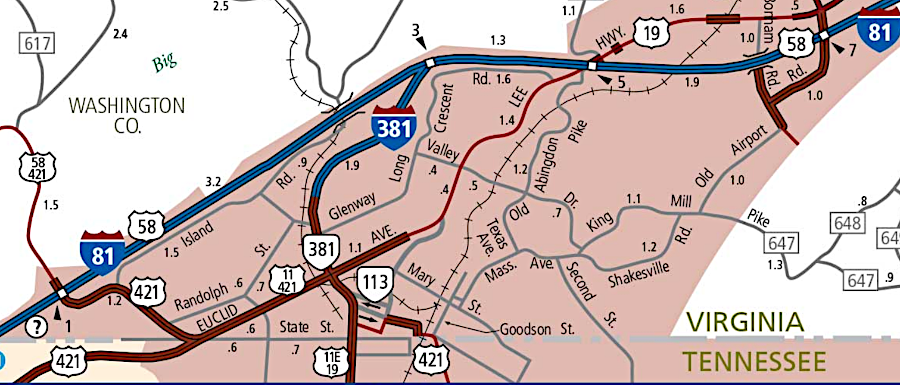

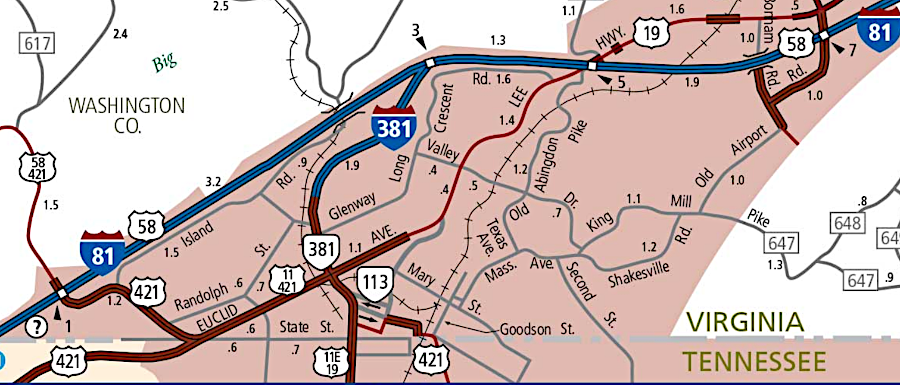

If the first number is odd, then the minor interstate is a spur that connects to a different major interstate or dead ends, such as I-581 in Roanoke and I-381 in Bristol.15

I-381 is a dead-end spur from the main interstate, so it uses an odd number (3) at the start of its three-number designation

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Virginia Cities In Detail - Bristol

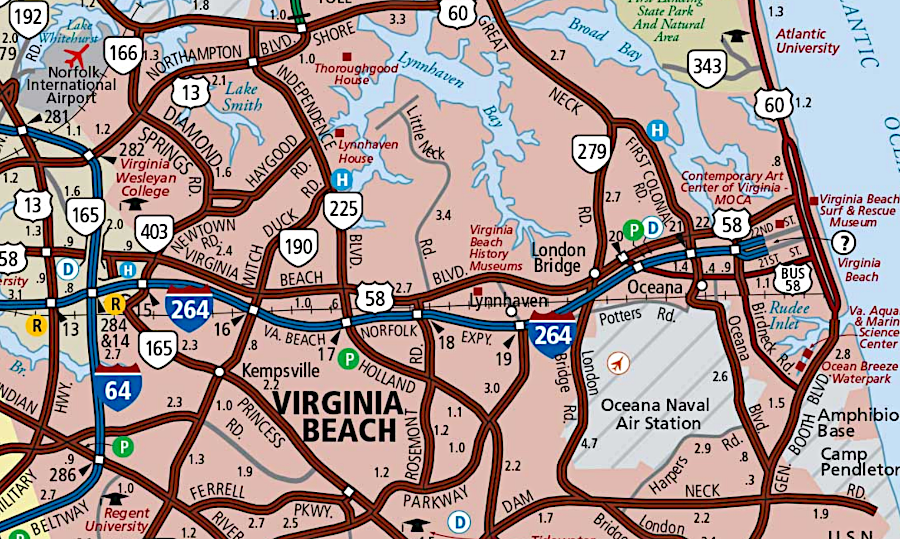

I-264 is a dead-end on its eastern edge, but starts with an even number (2) because it connects to I-64 at two locations further west

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Virginia Cities In Detail - Virginia Beach

Names are given to Virginia highways as well as numbers. For example, the General Assembly designated what is now Route 29 from Danville to Warrenton as the Seminole Trail in 1928. That may have been an effort to attract the tourist trade driving to Florida. Other portions of the road were designated as the Lee Highway, memorializing the leader of the Army of Northern Virginia for the last three years of the Civil War. In 1994, as the "greatest generation" of World War II veterans were dying off and the 50th anniversary of the invasion of Europe was commemorated, the state legislature also designated Route 29 as the 29th Infantry Division Memorial Highway. That name honored of the division's service in World War II, particularly on D-Day.16

The General Assembly has retained authority for assigning names to roads in the system of Primary Highways and delegated that authority to local governing bodies for just roads in the Secondary system, with one exception. The Commonwealth Transportation Board can name state highways, bridges, interchanges, and other transportation facilities to honor someone who is already dead, or a group of people such as Vietnam Veterans.

Local governments can request action by the Commonwealth Transportation Board, after passing an official resolution of support for a name of a highway or bridge. Individuals, businesses, and non-government organizations also can request the General Assembly (rather than the Commonwealth Transportation Board) to name a highway or bridge.

Cities and the counties of Arlington and Henrico, which never transferred their local roads to the state under the 1932 Road Act, have authority to change names of primary roads within their boundaries. Counties lack that authority, since Virginia is a "Dillon Rule" state and the General Assembly has granted road naming authority only to cities.

In 2018, the City Council of Alexandria used its power. It renamed as "Richmond Highway" that portion of Route 1 through the city, a stretch which the General Assembly had designated as part of the Jefferson Davis Highway in 1922.

Arlington County wanted to rename its portion of Jefferson Davis Highway, but needed state action. That was facilitated by an opinion from the Attorney General that the Commonwealth Transportation Board, as well as the General Assembly, could rename the highway. In 2019, the Commonwealth Transportation Board agreed to drop the Jefferson Davis Highway name and use "Richmond Highway" in Arlington as well. However, special legislation was passed by the General Assembly in 2021 in order to allow Arlington County to change the designation of US 29 as "Lee Highway."

In 2021, the General Assembly decided to rename all stretches of Route 1 as Emancipation Highway. Local jurisdictions were given the opportunity to choose a different name, but had to act before the end of 2021. Fredericksburg endorsed Emancipation Highway, but nearby jurisdictions opted for alternatives. Stafford County chose Richmond Highway, Spotsylvania County chose Patriot Highway, and Caroline County considered yet another name - Historic Route 1.

Residents who had used "Jefferson Davis Highway" as their address had to get a new drivers license. Businesses had to print new business cards and other items with their contact information, and local jurisdictions had to change street signs. The General Assembly mandated a name change, but provided no funding for changing addresses and signs. Fredericksburg estimated the cost at $90,000, while Spotsylvania County projected a $380,000 cost.17

In 2022, the City of Fairfax adopted new names for 14 city streets to replace names associated with slavery and the Confederacy. Nine of the streets in the Mosby Woods community were renamed, and Mosby Woods Drive became Fair Woods Drive. Because the City of Fairfax is respnsible for its road network, the city council did not have to obain state permission before changing the names.18

Though only the General Assembly or Commonwealth Transportation Board can assign a name to transportation facilities in the Primary System, local governments can name new roads in the Secondary System (highways with numbers below 600). There is no requirement for two local jurisdictions to use the same name for a continuous stretch of road that crosses city/county boundaries. Even straight roads that pass through two subdivisions within the same town, city or county may have different names.

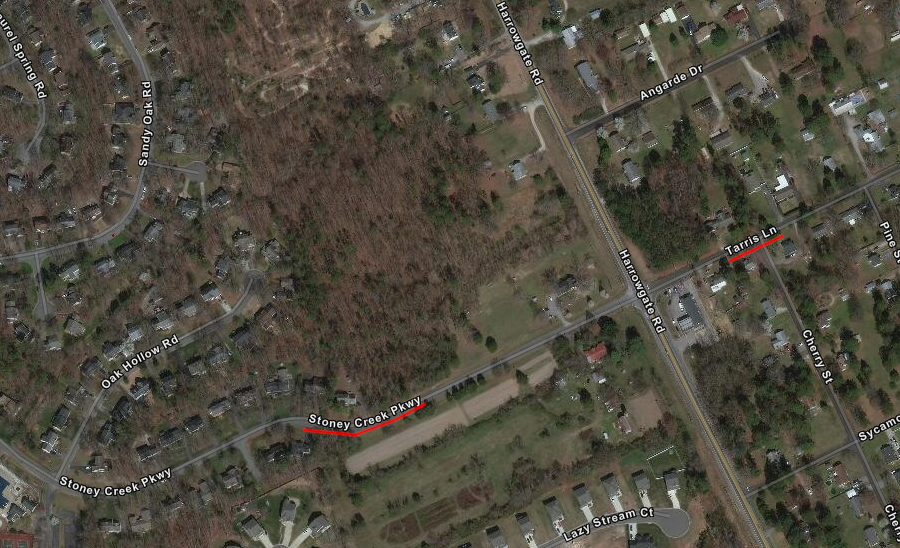

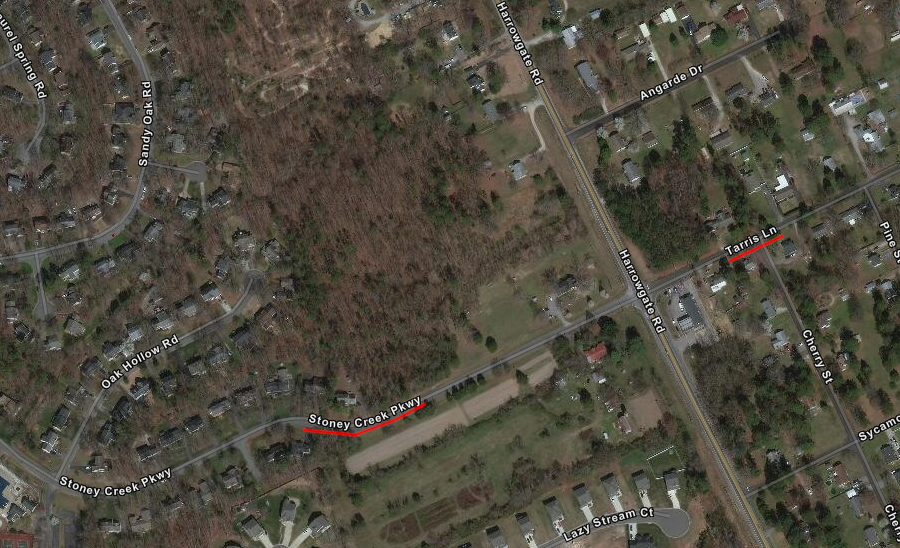

In Virginia, developers of a new subdivision typically choose the names of roads they build. It is common for developers to choose different names for their stretches of road, creating unique identities for their subdivisions but creating confusion for pizza and Amazon delivery drivers. A bewildering number of names have been applied to paved highways - road, street, lane, circle, court, trace, parkway, interstate, etc. Terms for roads are used loosely in casual conversations; a standard joke is that "we park on driveways and drive on parkways."

Stoney Creek Parkway and Tarris Lane in Chesterfield County have different names, but the same functional classification as "collector" roads (as opposed to "arterial" or "local" roads)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

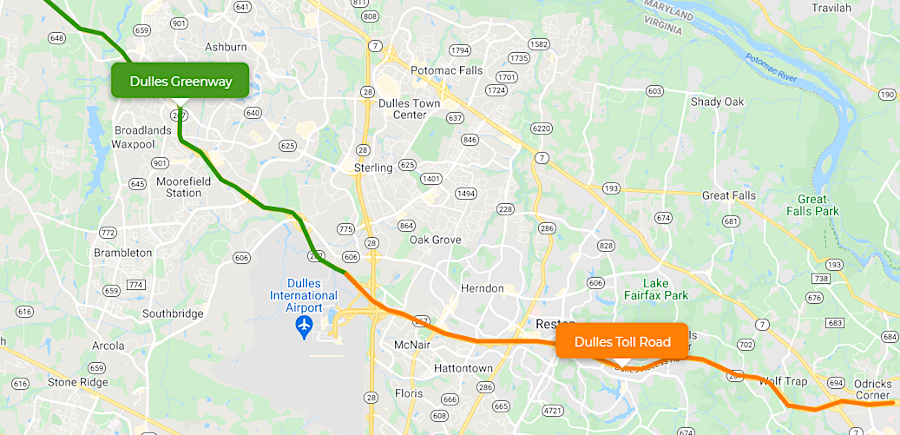

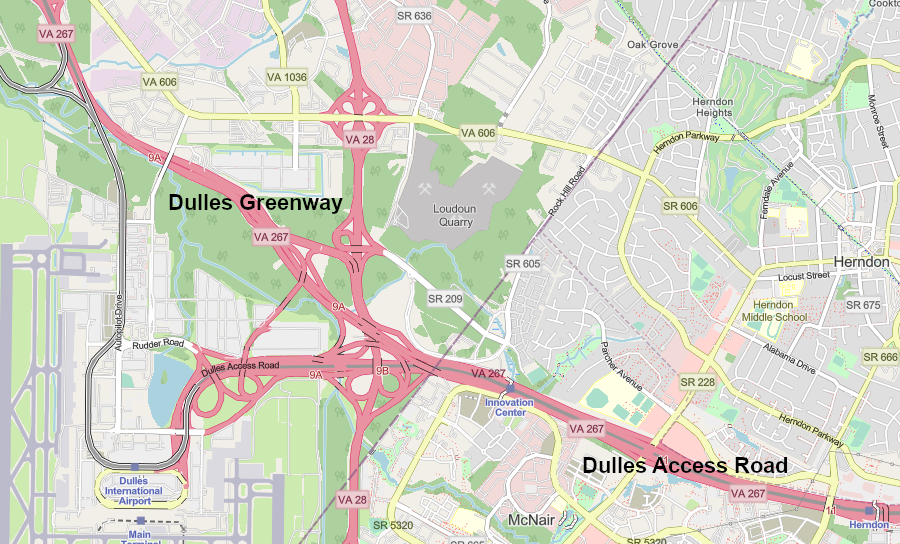

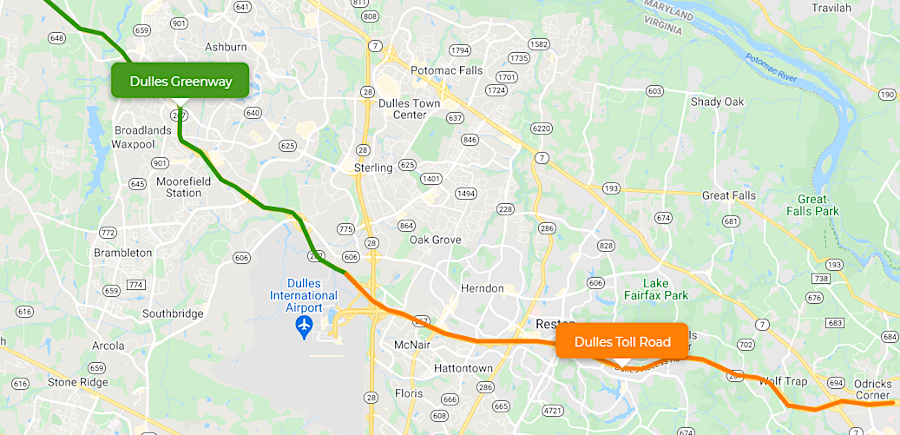

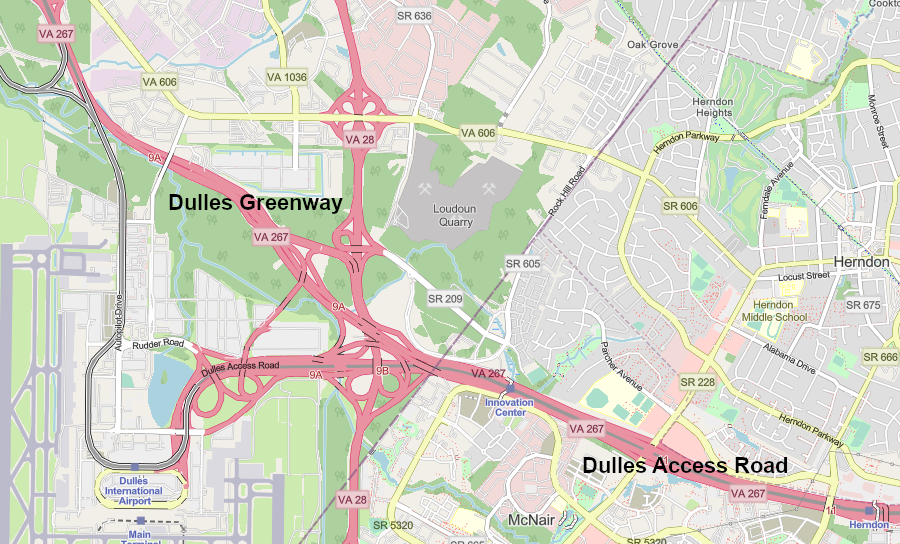

The Dulles Greenway, a private toll road in Northern County, is included in the state numbering system as Route 267.19

the Dulles Greenway is a private toll road, but is still included in the state highway numbering system (together with Dulles Toll Road) as Route 267

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Toll Roads in Virginia and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Links

References

1. Wm. J. Hinke, "Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel from Berne, Switzerland, to Virginia, October 2, 1701-December 1, 1702. Part II," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 24, Number 2 (April, 1916), p.115, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243509 (last checked October 10, 2022)

2. "Restored rock road sign in Halifax County dates back to era of George Washington," The Gazette-Virginian, October 9, 2022, http://www.yourgv.com/news/local_news/restored-rock-road-sign-in-halifax-county-dates-back-to-era-of-george-washington/article_66fcd44a-4805-11ed-b0c5-33e359f6b3e1.html (last checked October 10, 2022)

3. "Report of the Joint Board on Interstate Highways, October 30, 1925," Bureau of Public Roads, November 18, 1925, p.6, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015021099604; Richard F. Weingroff, "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm; "'The Most Convenient Wayes' - A History Of Roads In Virginia," Virginia Department of Transportation, 2006, pp.23-28, http://www.virginiadot.org/about/resources/historyofrds.pdf; "Fifty Thousand Miles of National Highways Proposed by the National Highways Association," Library of Congress, 1914, https://lccn.loc.gov/2021668520 (last checked April 16, 2022)

4. "Fighting for booze equality on 'Alcohol Alley'," R Street, February 27, 2017, https://www.rstreet.org/2017/02/27/fighting-for-booze-equality-on-alcohol-alley/

5. "Who We Are," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/about/; "Milestones for U.S. Highway Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration," Federal Highway Administration, Public Roads, Volume 59, Number 4 (Spring 1996), https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/96spring/p96sp44.cfm; "CIA's Mysterious Neighbor: FHWA," Overt Action, http://www.overtaction.org/2015/05/cias-mysterious-neighbor-fhwa/ (last checked March 21, 2018)

6. Richard F. Weingroff, "'Clearly Vicious as a Matter of Policy': The Fight Against Federal-Aid - Part One: Unease in the Golden Age" Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/hwyhist04a.cfm#s02 (last checked March 21, 2018)

7. "E. W. James on designating the Federal-aid system and developing the U.S. numbered highway plan," Federal Highway Administration, February 21, 1967, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/ewjames.cfm (last checked March 21, 2018)

8. Richard F. Weingroff, "Celebrating A Century of Cooperation," Public Roads, Federal Highway Administration, September/October 2014, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/14sepoct/03.cfm; "'The Most Convenient Wayes' - A History Of Roads In Virginia," Virginia Department of Transportation, 2006, p.30, http://www.virginiadot.org/about/resources/historyofrds.pdf (last checked June 13, 2021)

9. Richard F. Weingroff, "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm (last checked March 21, 2018)

10. "Report of the Joint Board on Interstate Highways, October 30, 1925," Bureau of Public Roads, November 18, 1925, p.17, p.19, p.47, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015021099604; Richard F. Weingroff, "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm (last checked March 21, 2018)

11. Richard F. Weingroff, "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm (last checked March 21, 2018)

12. "Report of the Joint Board on Interstate Highways, October 30, 1925," Bureau of Public Roads, November 18, 1925, pp.45-60, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015021099604 (last checked March 21, 2018)

13. "E. W. James on designating the Federal-aid system and developing the U.S. numbered highway plan," Federal Highway Administration, February 21, 1967, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/ewjames.cfm (last checked March 21, 2018)

14. Richard F. Weingroff, "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/numbers.cfm; "E. W. James on designating the Federal-aid system and developing the U.S. numbered highway plan," Federal Highway Administration, February 21, 1967, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/ewjames.cfm; "U.S. 2: Houlton, Maine, to Everett, Washington," Federal Highway Administration, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/us2.cfm; "Route 66 Overview," National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/route-66-overview.htm (last checked June 13, 2021)

15. "The Interstate's Forgotten Code," CGP Grey, https://youtu.be/8Fn_30AD7Pk (last checked June 1, 2022)

16. "US 29 through Virginia - The Seminole Trail," GribbleNation, January 7, 2017, http://www.gribblenation.org/2017/01/us-29-through-virginia-seminole-trail.html (last checked June 12, 2021)

17. "Naming Bridges and Highways," Virginia Department of Transportation, http://www.virginiadot.org/info/faq-highway-named.asp; "Naming highways, bridges, interchanges, and other transportation facilities," Title 33.2. Highways and Other Surface Transportation Systems, Chapter 2. Transportation Entities, Section 33.2-213, Code of Virginia, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title33.2/chapter2/section33.2-213/; "Who can change the names of roads in Virginia?," WTOP, August 20, 2017, https://wtop.com/arlington/2017/08/can-change-names-road-virginia/; "Virginia agrees to let Arlington rename Jefferson Davis Highway," Washington Post, May 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/2019/05/15/e174356e-76b8-11e9-bd25-c989555e7766_story.html; "Arlington can rename Jefferson Davis Highway without going through legislators, AG opinion says," Washington Post, March 22, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/arlington-can-rename-jeff-davis-highway-without-going-through-legislators-ag-opinion-says/2019/03/22/c8cff8fc-4cb7-11e9-9663-00ac73f49662_story.html; "State Bill Allows County to Rename Lee Highway, But 'Loving Avenue' Name Unlikely," ArlingtonNOW, February 24, 2021, https://www.arlnow.com/2021/02/24/state-bill-allows-county-to-rename-lee-highway-but-loving-avenue-name-unlikely/; "How many names will U.S. 1 have come Jan. 1?," Free Lance-Star, September 1, 2021, https://fredericksburg.com/news/local/how-many-names-will-u-s-1-have-come-jan-1/article_f3d7d500-939c-56ec-9fe3-412e7edce144.html (last checked September 1, 2021)

18. "Fairfax City Changing Confederate Street Names," Fairfax Connection, December 7, 2022, http://www.fairfaxconnection.com/news/2022/dec/07/fairfax-city-changing-confederate-street-names/ (last checked December 24, 2022)

19. "VA State Route 267," Roadnow, https://roadnow.com/us/va/road_description.php?id=r10004378&road=VA-State-Route-267 (last checked August 9, 2021)

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places