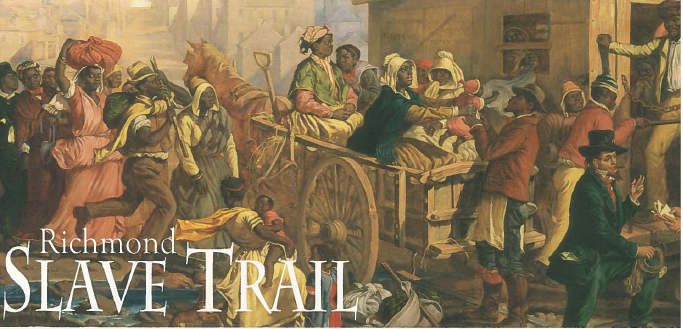

the trail to the James River landing where slaves were loaded on ships is now commemorated in Richmond

Source: Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission, Slave Trail Map

the trail to the James River landing where slaves were loaded on ships is now commemorated in Richmond

Source: Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission, Slave Trail Map

Representing the heritage of slavery may be the toughest challenge at historical sites in Virginia.

Civil War re-enactments were common across Virginia after the centennial in 1961-65, with people dressing in period uniforms. Typically the re-enactors were all white men, often older and heavier than the soldiers they represented. Units re-enacting the US Colored Troops (USCT) were rare. The enslaved people that supported Confederate officers in the 1860's were invisible in the re-enactments.

At Colonial Williamsburg and various historic sites in Virginia, characters dressed in costume present historical interpretation. Only after 2000 was it possible to find characters interpreting the institution of slavery. Obviously, no historic site is going to re-enact the whippings and other cruel punishments imposed upon recalcitrant slaves, but in the Twentieth Century the institution of slavery was marginalized in historic interpretation. It was easy to find a famous Virginia plantation house that offered no more than passing comments about the majority of people who lived there.

Some historic plantations such as Mount Vernon have built re-creations of slave cabins and marked the locations of slave graveyards. Other than Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, Colonial Williamsburg, and the Booker T. Washington Memorial, however, few sites in Virginia dedicated substantial resources towards presenting the slave experience to modern visitors before the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. The colonial plantations along Route 5, between Richmond and Williamsburg, preserve the houses of the wealthy gentry. Tourism marketing highlighted the life of the wealthy who lived in those homes. Tourists were expected to be less interested in struggling with their emotions if challenged to explore the difficult lives of the majority of residents at those sites, the enslaved workers.

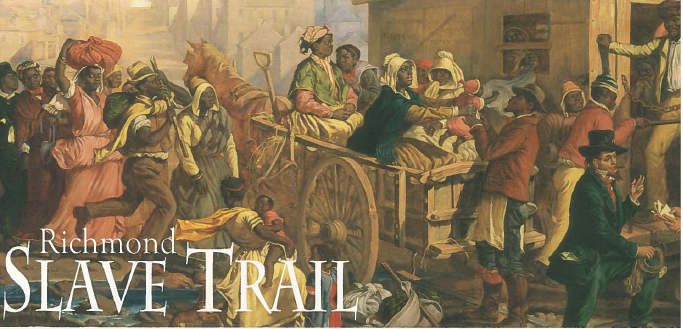

Gunston Hall is owned by the state of Virginia, but interpretation there is provided by a non-government partner. The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America and the state government have restored the plantation house at great expense, but in 2020 the dwellings occupied by slaves who worked the fields was largely missing from the interpretive landscape. The story of slavery was not omitted completely at Gunston Hall, but a visitor could easily learn about George Mason's life without understanding why he had so much free time to write letters about political philosophy and quarrel with George Washington.

the slave quarters at "Log Town" in the woods west of the mansion at Gunston Hall are mentioned in some interpretive signs, but none of those pine log structures were re-created like other wooden outbuildings

Smithfield Plantation in Blacksburg mimicked the Gunston Hall approach. That plantation was founded in the 1770's not just by Col. William Preston, but also by slaves that he purchased and brought west of the Blue Ridge.

In the 1840's, a Preston descendant bought slaves in Norfolk and brought them west to Smithfield Plantation. A slave in that group from Norfolk named Jim Barbour sought to escape and ultimately drowned in the Ohio River. For years, visitors to the plantation could learn the story of the Prestons without getting the story about slaves like Jim Barbour, but as noted in news article:1

Colonial Williamsburg seeks to provide an authentic representation of colonial life, but its first efforts to demonstrate interactions between slaves/masters stimulated strong reactions from tourists. Some visitors interrupted historic presentations to challenge the "slave" to explain why they are not setting a "good example" to children by asserting basic human rights. Colonial Williamsburg may have considered it to be an interpretive success to engage visitors so deeply and to get them to discover the limited choices in the 1770's for enslaved people, but getting guests upset is rarely a successful business model.2

One solution was expensive: double the number of interpreters and put one in traditional garb acting as a slave, but have another interpreter in modern dress. The interpreter acting as an enslaved person could avoid breaking out of character, while the interpreter in modern dress could articulate the context and history of the "peculiar institution" of slavery.

George Washington, a farmer with his slaves

Source: Library of Congress, Life of George Washington--The farmer, painted by Junius Brutus Stearns

Former governor Douglas Wilder (the first African American to be elected governor in the United States, and the grandchild of a slave) had plans to make the story of slavery into a major tourist attraction by opening a museum of slavery. He flirted with locating the U.S. National Slavery Museum in the Jamestown area, where slaves first arrived in Virginia. He then rejected Richmond, and selected Fredericksburg.3

Even after Governor Wilder was elected mayor of Richmond, he still rejected proposals to locate the museum there. After the old Confederate cannon manufacturing plant, Tredegar Iron Works, re-opened on October 7, 2006 as the Civil War Visitor Center, the new exhibits stimulated discussion along the lines of "if we could get the mayor to move the slavery museum to Richmond, the city could tell the whole story of the Civil War here..."Wilder chose Fredericksburg in part because it was closer to the population center in Northern Virginia, but also in part because the major developer in Fredericksburg donated 38 acres for the museum at the "Celebrate Virginia" development. Wilder's fundraising efforts to build a museum failed, and after a few sculptures were installed no construction was ever started.

Wilder was too busy as mayor of Richmond to build a museum in time for the 2007 commemoration of the last 400 years of English settlement in Virginia, and his prickly personality was a factor as well. During the major recession starting in 2008, the City of Fredericksburg lost patience and rejected Wilder's request to eliminate the property taxes on the museum site. That led to a series of lawsuits over control of the 38 acres.4

the Fredericksburg location (red X) for the U.S. National Slavery Museum would have been highly visible from I-95

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The slavery museum project went into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2011. Bankruptcy temporarily blocked Fredericksburg from selling the property in order to collect the property taxes. In 2013 the parcel was supposed to be transferred to a new owner, who obtained city approval to build a baseball stadium on the site and would pay the back taxes. That transfer was supposed to end plans for a slavery museum in Fredericksburg.

The saga continued, however. The ballpark plans collapsed when site development cost far exceeded initial estimates and the Hagerstown Suns dropped plans to move the Class A baseball team to Fredericksburg. In 2015 the city renewed efforts to force a sale of the 38-acre site and collect over $650,000 in back taxes and interest.5

The failure in Fredericksburg triggered a new effort in Richmond to locate a slavery museum there. In 2014, Governor Wilder endorsed building a location in Shockoe Valley near the old Lumpkin Slave Jail. The former governor was famous for his independent streak, which limited the willingness of others to work with him. He failed to tell the Virginia Commonwealth University about his plans before he recommended that the National Slavery Museum be located in a building currently being used by the VCU medical school.6

Virginia missed its window of opportunity to open a slavery museum before the Smithsonian Institution opened the $250 million National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in 2016.

If a slavery museum is ever completed in Richmond, attendance will demonstrate if there is a large-enough audience interested in slavery to support such a museum just 100 miles away from the Smithsonian facility. The design of the museum, as well as the distance, will be key factors. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has demonstrated that competition from Federally-supported art museums100 miles away does not limit the ability of Virginia facilities to thrive in Richmond.

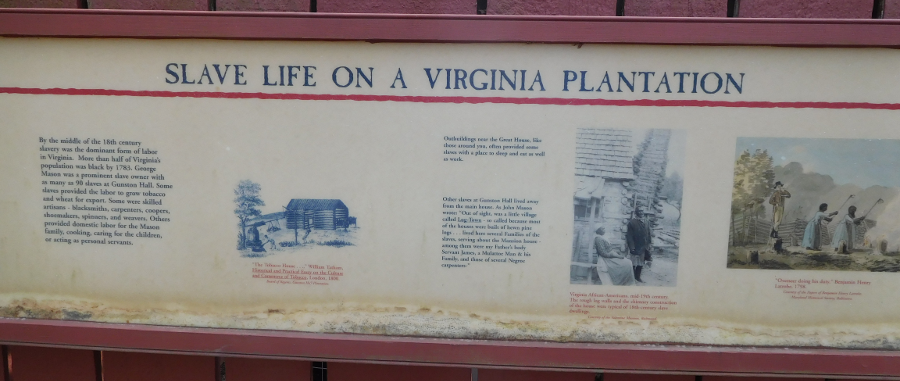

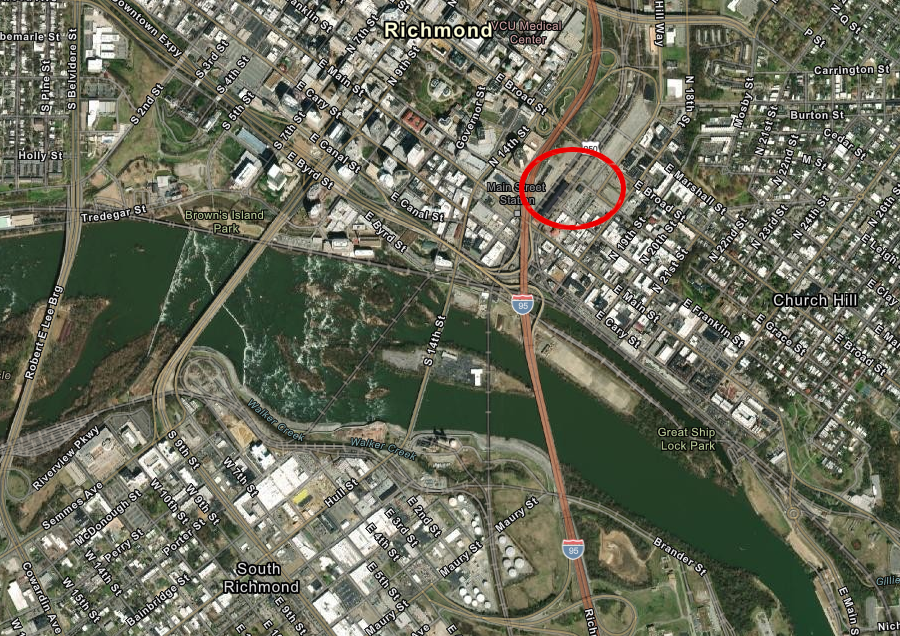

In 2020, Richmond officials dedicated $2 million for the planning and design of a slavery museum in in Shockoe Bottom, next to Main Street Station. That area included the site of Lumpkin's Slave Jail ("Devil's Half Acre") and the historic center of the marketing of enslaved people. Total cost of the planned museum was estimated initially at $20-$50 million.

By the start of 2022, the city was planning a $200 million complex, and there were commitments of $40 million in state and local funding. A feasibility study produced:7

a slavery museum in Richmond near the old Lumpkin Slave Jail would be highly visible from I-95

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Governor Wilder was not the first to experience failure by trying to interpret slavery. The Walt Disney Corporation proposed to incorporate the slavery experience in the "Disney America" theme park. The park was planned for western Prince William County, near Haymarket and not far from DC.

Why there, rather than in Charleston, South Carolina or near Jamestown? Disney hoped to attract some of the tourists that already came to Washington, DC. Disney America might grow into a destination resort over time, drawing visitors just to see the theme park - but in the short run, the facility would benefit from tourists already coming to the national capital.

The historical community opposed the Disney America project. The primary concern was protecting Manassas National Battlefield Park from development similar to sprawl surrounding Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. The Disney publicity campaign to soften opposition was damaged when a spokesman, referring to the historical accuracy planned for the theme park, suggested visitors would get an authentic experience:8

The idea of visitors getting an authentic experience with slavery, as either master or slave, was not helpful to the company's effort to generate political support. Disney abandoned the Disney America proposal in 1993, and the site was developed into residential subdivisions..

In 2010, Governor Bob McDonnell triggered a public relations uproar when he issued a proclamation at the request of the Sons of Confederate Veterans declaring April to be Confederate History Month. McDonnell's proclamation was designed in part to increase tourism during the 150th Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, but his statement did not mention slavery. The omission stirred memories of similar proclamations by Governor Allen and Governor Gilmore, which were perceived as racially insensitive. McDonnell quickly apologized for the omission, and in his final budget proposed $5 million for a slavery museum in Richmond.

Governor McDonnell sought to support tourism in Virginia through commemoration of African-American heritage, as well as through commemoration of the Civil War. Left unclear is whether tourists are interested in slavery. One assessment is that slavery and tourism, to many Americans, do not mix, and one historian even titled an essay "Nobody Knows the Troubles I've Seen, But Does Anybody Want to Hear about Them When They're on Vacation?"9

modern skyline of Richmond - once the capital of the Confederacy and a major slave market

Fredericksburg officials debated since 1924 whether to maintain one local memento of slavery, the slave auction block on the corner of Williams and Charles streets in the city's downtown. The chamber of commerce proposed removing in in order to increase tourism. In 2019, two years after the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville remobilized public concern about the reminder of slavery, City Council finally decided to move the sandstone block off the public street and place it in the Fredericksburg Area Museum.10

Plans to incorporate the story of enslaved workers at the Executive Mansion, the home of Virginia's governor in Richmond, advanced during the terms of Terry McAuliffe and Ralph Northam. New staff was hired and the kitchen in the building’s annex, where enslaved children as young as 10 and enslaved adults worked 15-hour days, was revised to serve as the center of interpretive tours that told a more-complete story of life in the house. The initiative was put on hold after the election of Glenn Youngkin as governor in 2021. He reassessed plans for the kitchen to be converted into an educational room for schoolchildren, and the historical specialist in charge of the project resigned her position.

While underway, the project identified roughly 20 descendants of enslaved people who had worked at the mansion, and at plantations of governors who brought them to the mansion. The director of community initiatives for Virginia Humanities commented about the project's capacity to reveal the landscape of slavery:11