wetland at mouth of Neabsco Creek, at Leesylvania State Park

wetland at mouth of Neabsco Creek, at Leesylvania State Park

Technically, wetlands are:1

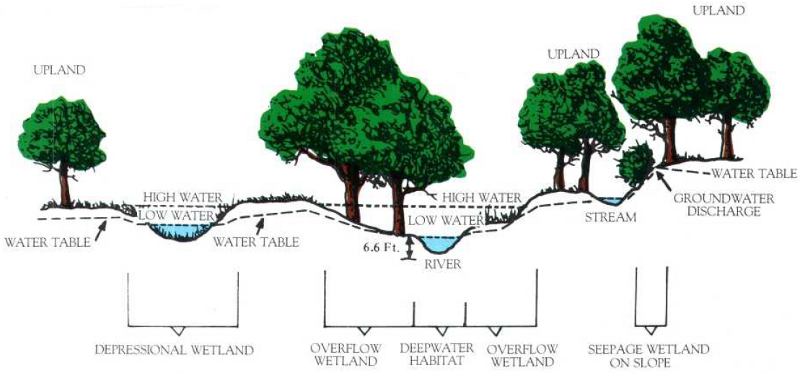

Wetlands do not have to have standing water 12 months of the year, but soils and plants must reflect the frequently-high water table. The ecological character of a wetland is determined by sustained inundation. Organisms in "hydric soils" consume the oxygen, and water blocks more oxygen from diffusing into the soil. The presence of the limited number of plant species that thrive in oxygen-deprived soils is a clue that a particular site is a wetland.

Most plant species require "dry feet," roots not saturated with water for a large percentage of the year. Such plants are most common on uplands, where raindrops flow from the surface through the soil and there is a "vadose" zone in which the gaps between soil particles are filled with air. In wetlands, most gaps between soil particles are saturated with groundwater and the water table is at or near the surface.

During a dry period a wetland may not have any surface water, but the distinctive character of soil and vegetation is still obvious to a trained wetland specialist. The type of soil and vegetation, more than the presence or absence of water on a particular hot August day, define what is wetland vs. upland. Developers who propose cutting down the cattails to disguise the existence of a wetland, hoping to expand the acreage that can be paved and on which structures can be built, will not be successful; soils alone will still provide the evidence.

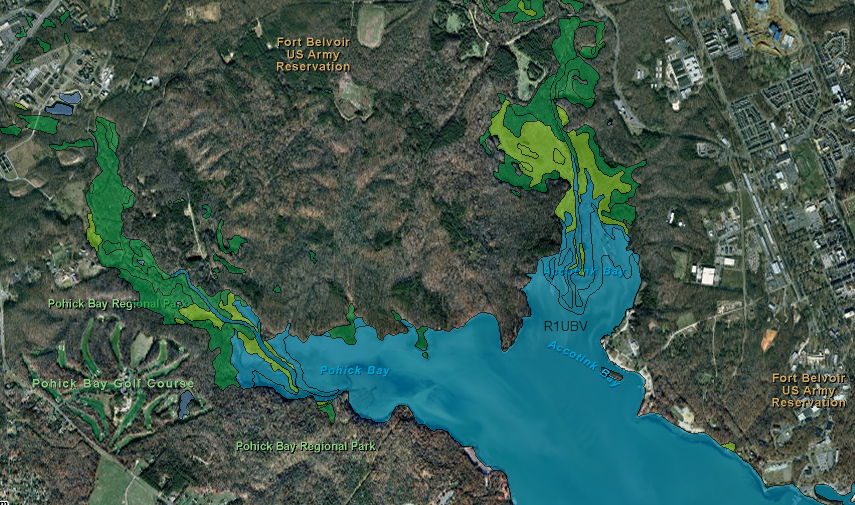

wetlands mapped at mouth of Pohick Creek and Accotink Creek

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service National Wetlands Inventory, Wetlands Mapper

Virginia wetland statistics (calculated at the end of the 1970's):2

1 million acres of wetlands of all types

72% are palustrine vegetated wetlands ("palustrine" wetlands are located in fields/forests and on the edge of streams - but not adjacent to large lakes or on the edge of tidal waters)

23% are estuarine wetlands ("estuarine" wetlands are associated with tidal waters, east of the Fall Line)

72% of all wetlands are located in the Coastal Plain

22% of all wetlands are located in the Piedmont

6% of all wetlands are in the other physiographic provinces

Wetlands are now a valued ecological resource in Virginia. They provide essential habitat, particularly for salamanders and frogs. Wetlands provide stormwater management services, capturing runoff during/after a storm before the rainwater reaches streams and erodes the channel.

Isolated wetlands, low areas without a stream connecting them directly to a river, still intercept nutrients as well as sediment. Plants take advantage of the nutrients. In addition to creating habitat that is especially rich biologically wetlands also provide natural pollution control.

a spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) from a vernal pool at Bull Run Mountains Natural Area Preserve in February, 2023

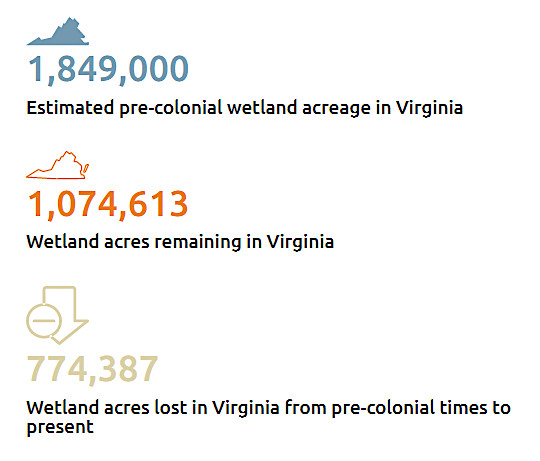

Virginia still has 146 named swamps, but in the 400 years of settlement after Jamestown 42% of the natural wetlands were drained or filled for agriculture, industrial facilities, roads/ports, and urban/suburban development. In particular, estuarine and palustrine vegetated wetlands were lost. The "lost" acres have been converted into upland (filled in with dirt and other materials) or open water through dredging or erosion.

At the same time, artificial construction of farm ponds and reservoirs created an increase in open water areas.3

Today, government policy is to ensure "no net loss" of wetlands, ideally by avoiding alteration of a natural wetland. As described by the Environmental Protection Agency:4

Projects that destroy even tiny wetland areas are required to mitigate the loss by creation of artificial wetlands of an equivalent type. Destruction of a forested wetland requires two acres of new forested wetland for every acre destroyed, while destruction of a scrub-shrub wetland must be mitigated by a 1.5-to-1 ratio.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issues Virginia Water Protection Permits for non-tidal wetlands, and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) manages changes to tidal wetlands. State permits are required under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act. The Federal government authority to regulate wetlands is based on Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, processed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Section 404 requires a permit before dredged or fill material may be discharged into waters of the United States.

wetlands locations

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, MidAtlantic Wetlands: A Disappearing Natural Treasure

Today:5

estuarine wetlands on eastern side of Eastern Shore

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wetlands Inventory, Wetlands Mapper

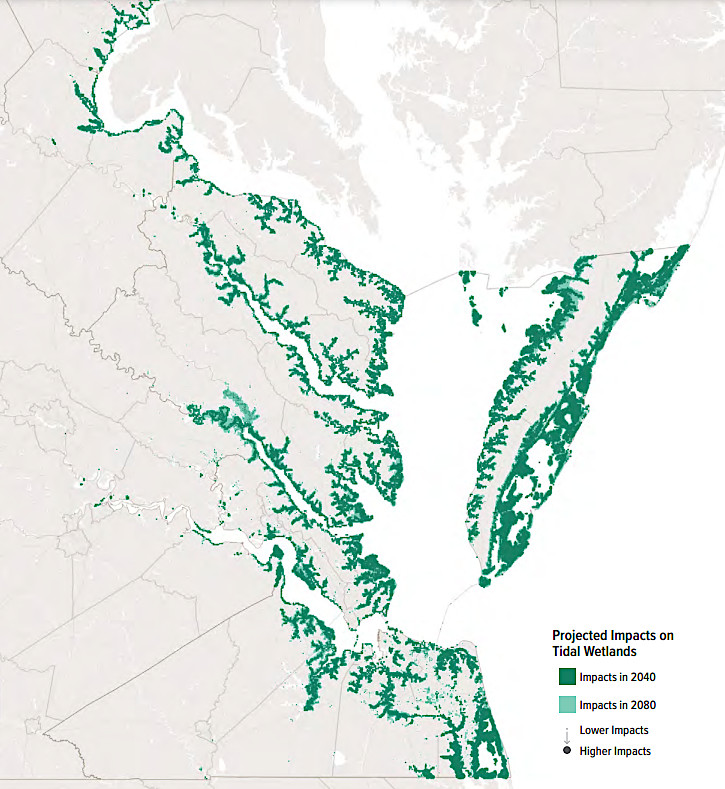

If no action is taken to address climate change, the worst-case scenario, then by the year 2100 over 40% of the remaining tidal wetlands could be drowned by sea level rise. If greenhouse gas emissions are reduced and sea level rises slowly, shorelines can migrate slowly into current uplands.

The percentage that will be lost depends upon whether sea level rises quickly, and on how many miles of shorelines have been "armored" with bulkheads or seawalls that prevent existing wetlands from migrating. The 2021 Virginia Coastal Resilience Plan was even more pessimistic. It predicted that between 2020 and 2080:6

Virginia has lost over 40% of its natural wetlands since 1607

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Wetland Preservation in Virginia

89% of the 190,000 acres of tidal wetlands still remaining in 2020 could be converted to open water by 2080

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan, Phase 1 (p.137)

Both the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issue permits for dredging and filling wetlands. The Federal permits are required by Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (Public Law 95-217). A list of public notices being considered by the Norfolk District of the Corps will almost always include a few announcements about 404 permit applications in Virginia.

The Federal government's right to control even minor land disturbance is based on the constitutional authority to regulate navigable waterways (including Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act passed in 1899). As described Section 320.2 of the Code of Federal Regulations:7

Mathews County wetlands

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wetlands Inventory

Filling wetlands will change the way water runs off into the navigable streams, such as the James River. The Corps is notorious in some quarters for its philosophy of building structures rather than preserving the natural environment, even when the economic (as well as environmental) costs of a waterway or dam exceed the benefits - but according to the Federal rules of the game, it's the Corps that determines what permits to approve or reject.

fronds of a sensitive fern offer a good clue that the soil moisture levels are high in the area

Defining the edge of a "jurisdictional" wetland is a judgment call that has significant impact on how a parcel of land could be developed. Different people can assess the soil and vegetation as it grades from wetland into upland, and draw the boundary of a wetland in different places.

Federal agencies, including the Department of Agriculture farming bureaus, the Department of the Interior wildlife conservation bureaus, and the Environmental Protection Agency, struggled to adopt one standard manual for mapping wetlands consistently. The Environmental Protection Agency and the Corps of Engineers now use the 1987 Corps of Engineers Wetlands Delineation Manual and Regional Supplements to define wetlands for the Clean Water Act Section 404 permit program.

Many developers hire contractors to delineate the boundaries of wetlands before drawing up detailed development plans, and specialists responsible for wetlands delineation must be trained in using the manual. Until 2023, the Corps of Engineers was responsible for reviewing delineations of wetlands in Virginia and determining if they met the necessary quality standards.

Determining the exact edge of a wetland involves both art and science. Delineation of a wetland boundary is not a cookbook process that any landowner can do. The Corps definition of wetlands recognizes that areas that are dry for much of the year can still be classified as wetlands. On-site reviews, not just examination of aerial photography, are required to determine exactly where the regulations require a permit based on the vegetation, soil, and hydrology.

The Corps advises landowners to request consultation if, in the Corps definition, an:8

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Bay 101: Wetlands

Wetland protection became a political issue in the Bush/Quayle administration, with claims that the "no net loss" commitment was a fraud because the definition of wetland was being narrowed to just areas with standing water throughout the year.

Though many farming/forestry activities were excluded by the US Congress from Section 404 regulation under the Clean Water Act, the American Farm Bureau Federation challenged the legal status of "isolated wetlands," places that are not directly connected to the navigable waters of the United States such as a vernal pool in a forested area away from a stream.

In 2006, the US Supreme Court determined that development of isolated wetlands with an ecologically-significant nexus could be regulated under the Clean Water Act. In the May 25, 2023 Sackett v. EPA decision, however, five justices declared that wetlands had to be "adjoining" rather than "adjacent" to streams.

Biologically, wetlands might exist anywhere. The Supreme Court ruled that "jurisdictional" wetlands subject to the Clean Water Act were more limited, and had to be indistinguishable from waters of the United States (WOTUS). To be regulated under Federal law, a wetland must be near a relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters, and have:9

The Virginia Farm Bureau and the National Association of Home Builders celebrated the decision, describing it as a victory for private property rights against Federal overreach. The Potomac Riverkeeper Network noted that the decision would remove Federal protection from 65% of wetlands nationwide and more than 80% of the streams.

In Virginia, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) assumed responsibility for reviewing delineations by certified private wetlands professionals. Virginia laws protecting wetlands, streams and even groundwater were broader than the Clean Water Act, and did not require a "continuous surface connection" with Waters of the United States.10

boardwalk across Neabsco Creek under construction on March 1, 2018

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey

vernal pools are wetlands which hold water seasonally, providing habitat long enough for egg masses of wood frogs and salamanders to mature before drying up in the summer