Philip Barbour chaired the 1830 convention that revised Virginia's constitution for the first time

Source: U.S. House of Representatives, Philip Pendleton Barbour

Philip Barbour chaired the 1830 convention that revised Virginia's constitution for the first time

Source: U.S. House of Representatives, Philip Pendleton Barbour

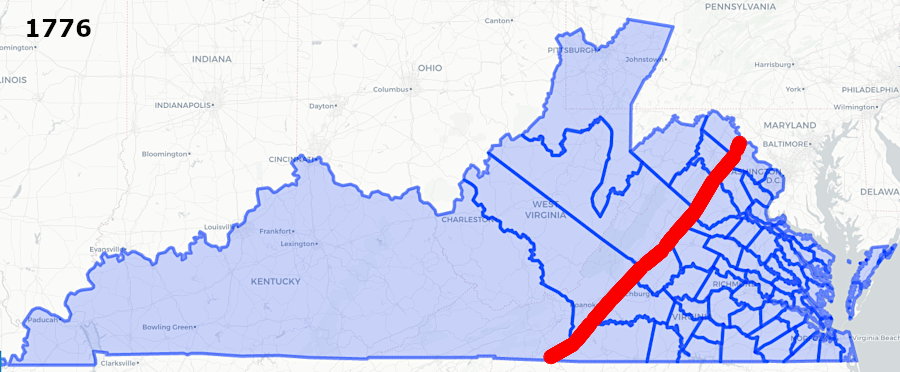

After 1776, Virginia's population grew west of the Blue Ridge. Two new members of the House of Delegates were added each time a new county was created by the General Assembly. However, political representation stayed unchanged for the State Senate.

Western counties exerted pressure for revising the 1776 constitution, or replacing it. When it became clear that the 1830 census would reveal the continuing population shift to the west, eastern leaders finally agreed to allow a vote on whether to hold a constitutional convention. The vote was 21,896 to 16,646 in favor.

Each of the 24 State Senate districts was entitled to send four representatives to the convention, which met between October 5, 1829 - January 15, 1830. When the Capitol was occupied by meetings of the General Assembly, the delegates met in the First Baptist Church. James Madison, who had participated in the 1787 convention that drafted the US Constitution and served as President of the United States between 1808-1816, was the most famous delegate in 1830.1

Since there was no authority to amend the 1776 document, the convention wrote a new constitution. Unlike the free-flowing text document in 1776, the 1830 document was structured with seven separate articles describing the functions of separate units of the government - legislature executive branch, and judiciary in particular. The proposed "amended constitution" was submitted to the voters and approved in 1830.

The ratification debates for the new constitution focused on proposals to expand the right of suffrage (i.e., who could vote), and to increase the number of members in the General Assembly elected from the western section of the state.

In the eyes of the white men living west of the Fall Line and especially west of the Blue Ridge, Tidewater counties had excessive political power in the General Assembly. The sectional split in the debate over the new constitution was clear during the convention.

The 1776 constitution had left unchanged the colonial-era requirement that in order to vote, a person had to be a white male citizen at least 21 years old, and had to own land or a house. Minimum property requirements were 50 acres of undeveloped land, 25 acres of land plus a house on it, or a house on a lot within a city or town. A lower percentage of families west of the Blue Ridge met that qualification. Of the 143,000 free white males in Virginia in 1829-30, only 40,000 owned real estate. Another 60,000 who paid taxes on personal property were not allowed to vote.

The eastern delegates argued that a person should own land and be a "freeholder" within a district where they voted; people who did not own land were not sufficiently connected to the district. The western delegates argued for extending suffrage to all white men, then compromised and argued for all white men who paid taxes. In the end, voting rights were expanded to include leaseholders who paid taxes on $20-25 of property, plus all tax-paying housekeepers who were heads of families.2

Under the 1776 constitution, each county elected two members of the House of Delegates. The General Assembly created large rather than equally small counties west of the mountains, so people outside of Tidewater has less political influence. The state's Board of Public Works funded far more transportation projects for residents living east of the Blue Ridge, expanding the economy of port cities and enhancing the value of farms east of the mountains. Unbalanced representation in the General Assembly meant that western residents lacked the ability to apply political pressure for a "fair share" of dollars for internal improvements.

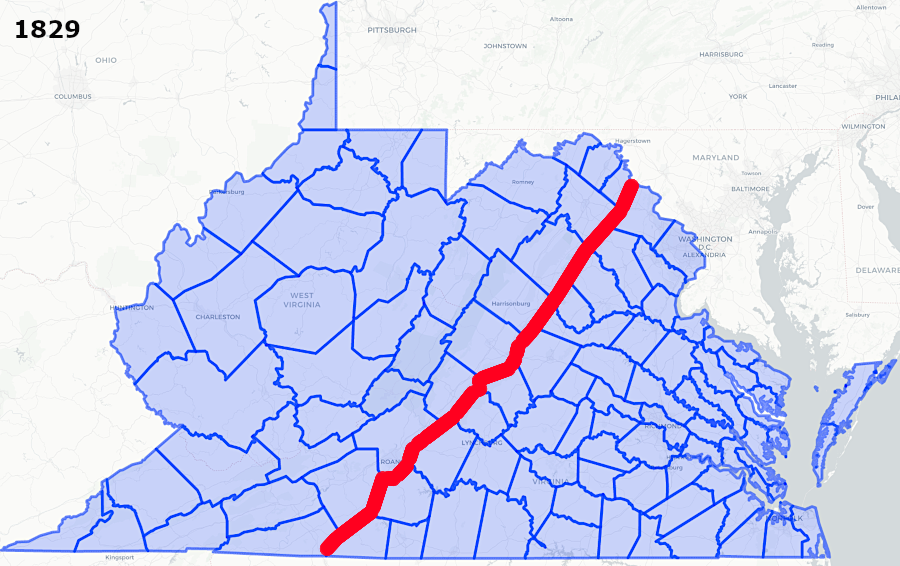

The State Senate was expanded from 24 to 32 members, with authorization to grow to a total of 36. Only 13 districts (40%) were located west of the Blue Ridge. The other 19 State Senate districts were located east of the mountain. Following the example set in 1776, the districts were divided into four classes, with the initial terms of the State Senators set at one, two, three, and four years.

The State Senate gained a slight amount of political power. The 1776 constitution empowered the State Senate to amend all laws passed by the House of Delegates except budgets, which had to be accepted or rejected in total. The 1830 constitution allowed the State Senate to propose amendments to budget bills as well:3

Boundaries of election districts within each division could be realigned to reflect population changes, but the east-of-the-Blue-Ridge vs. west-of-the-Blue-Ridge totals could not be altered. The ban on reapportionment between the two districts guaranteed that the Coastal Plain/Tidewater and Piedmont regions would continue to control the General Assembly, even as the percentage of the state's white population east of the Blue Ridge continued to decline as people moved into the Ohio River watershed.

The creation of new counties had led to 214 members being elected to the House of Delegates. That number was reduced to a more-manageable size of 134 members by defining a smaller number of districts for House of Delegates elections, with multiple counties within each district. Proposals for drawing those boundaries exposed the sectional differences again.

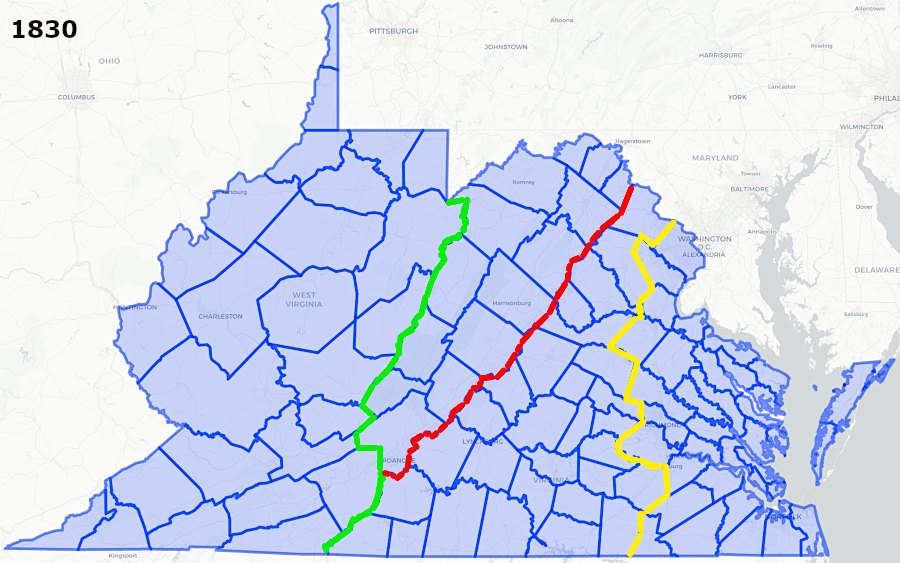

between 1776-1829, new counties created west of the Blue Ridge (red line) were few and large, minimizing their political influence in the General Assembly

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Eastern delegates argued that the majority of the taxable property lay east of the Blue Ridge. Government was supposed to protect property as well as life and liberty, and the region with the greatest property value should have the greatest representation.

Western delegates appealed for districts having boundaries drawn so each district would have the same number of white people. Enslaved people were concentrated in counties east of the Blue Ridge, so drawing boundaries based on the total population would tilt political power to the eastern side of the state. Former president James Monroe proposed drawing boundaries for the House of Delegates using only the white population and to use the total population (including enslaved people and free blacks) for the State Senate districts.4

The final political compromise was not based on any clear criteria. The state was broken in four sections for the election of 134 members to a smaller House of Delegates, and only 56 (42%) were for districts west of the Blue Ridge. The constitution specified that those sectional totals would remain unchanged following the census every decade, so population increases in the western counties would not be matched by increases in political power in the General Assembly:5

The 1830 constitution also said:6

The 1776 provision preventing ministers from being elected to the General Assembly was retained:7

The voters statewide ratified the new constitution in 1830 by 26,055 to 15,563, but west of the Allegheny Front most voters opposed it. Talk of secession from Virginia continued, and the Board of Public Works funded few transportation projects that would facilitate economic development in the Ohio River watershed.

In addition to suffrage and boundaries for electoral districts, there were other significant changes to the 1776 constitution. The term of the governor was changed from one year (with a limit of three appointments) to three years. No immediate second term was allowed, a pattern that continues today. The constitutional convention rejected a proposal for direct election of the governor by the voters; the General Assembly retained authority to choose the state's chief executive. The most-senior member of the Council of State (also called the Executive Council) still was designated to act in the place of the governor if necessary; the 1830 Constitution created no permanent lieutenant governor position.

The role of the governor was enhanced. His term was extended from one to three years, but re-election was prohibited. The Council of State was reduced from eight to three members, so the executive branch gained greater flexibility in reaching decisions. By 1830, fears of the governor becoming a new George III had been replaced by a desire for greater efficiency in state government, plus a recognition that the governor's authority to initiate a war had been assumed by the Federal government.8

The new constitution included within its language the 1786 Act for Establishing Religious Freedom. Revising that language, or passing legislation inconsistent with it, was no longer an option for the General Assembly. Changes would now require changing the state constitution, which was more difficult than just passing a law.

Western residents did not achieve what they desired; the 1830 constitution provided little substantive change regarding representation and political power for them. Political pressure to expand democracy and reduce the dominance of the Tidewater elite had to wait another two decades:9

The 1830 state constitution went into effect on July 1, 1830. Like its 1776 predecessor, it provided for no amendment process. Changes could occur only by calling another constitutional convention. When opposing the idea of creating an amendment process, John Randolph compared it to including provisions for a divorce in a marriage contract.10

the 1830 Constitution defined four sections for electing members to the House of Delegates

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries