the primary objective of the 1902 state constitution was to limit the ability of black men to vote

Source: Broadside 1901.N68, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia, 1901 Flyer--"No White Man to Lose His Vote"

the primary objective of the 1902 state constitution was to limit the ability of black men to vote

Source: Broadside 1901.N68, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia, 1901 Flyer--"No White Man to Lose His Vote"

Virginia's political elite decided to write a new state constitution after the Supreme Court legalized separate-but-equal treatment of blacks, including the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. The Williams v. Mississippi decision in 1898 made clear that the Supreme Court would allow voter discrimination, provided the tools used to suppress black voting were written in a race-neutral manner.1

The Democratic Party, with a white supremacist agenda, gained control of the General Assembly from the biracial Readjuster Party in 1883. After the Democrats won all statewide offices in 1885, the Readjuster Party dissolved. The racist perspective of the Democratic Party at the time was reflected in a comment by one delegate to he 1901-1902 constitutional convention:2

The General Assembly and governor proceeded to "redeem" control, finding ways to bypass the 15th Amendment. Mississippi started the process of changing a state constitution to require voters to pass literacy tests and pay poll taxes, tools which were used to discriminate against blacks and squeeze them out of the political process. By 1899, though blacks formed the majority of the state's population, 82% of white males and only 9% of black males were registered to vote.

Other states mimicked Mississippi and established mechanisms for segregation in new state constitutions - South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), North Carolina (1900), Alabama (1901), Virginia (1901), Georgia (1908), and Oklahoma (1910).3

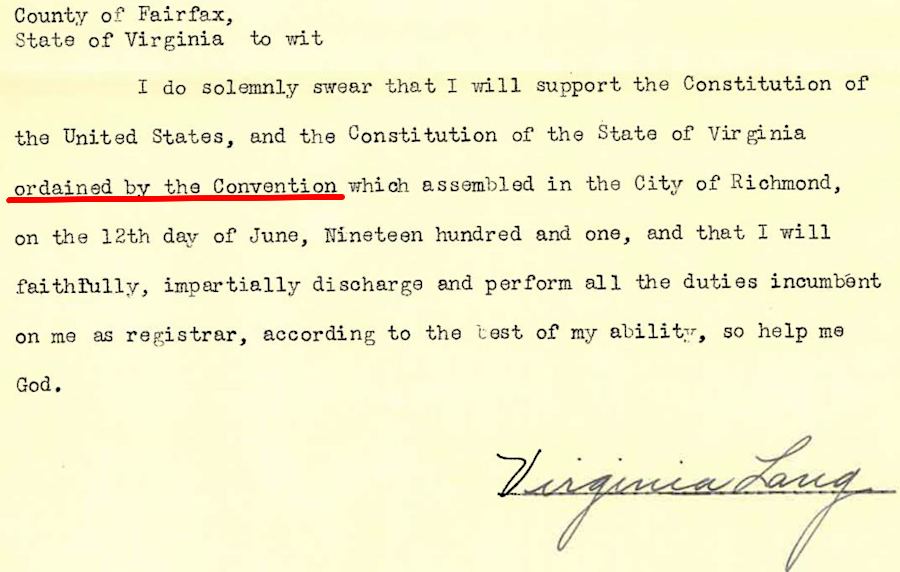

Virginia voters authorized a constitutional convention in 1900. On May 24, 1901, 100 delegates were elected to what has ended up being Virginia's last general constitutional convention. The delegates met from June 12, 1901-June 26, 1902.

The 1902 constitution created stricter voting requirements, substantially reducing the number of potential voters. Carter Glass made clear that the objective was to exclude black voters from the democratic process, using legal authorities according to the Supreme Court decisions:4

One delegate said equally bluntly that the:5

The 1901-1902 constitutional convention did not submit its new document to the voters for ratification. The convention simply declared that the new constitution replaced the 1870 constitution (as amended). There was no ratification vote, and the voters who were disenfranchised never got an opportunity at the ballot box to express their opposition. The Virginia Supreme Court ruled in the 1903 case Taylor v. Commonwealth:6

Local and state officials used the new controls created in the 1902 constitution to block many blacks (and poor whites) from registering to vote. The US Supreme Court interpreted the Fifteenth Amendment to prohibit disfranchising voters simply by race, but did allow restricting who could vote by administrative procedures.

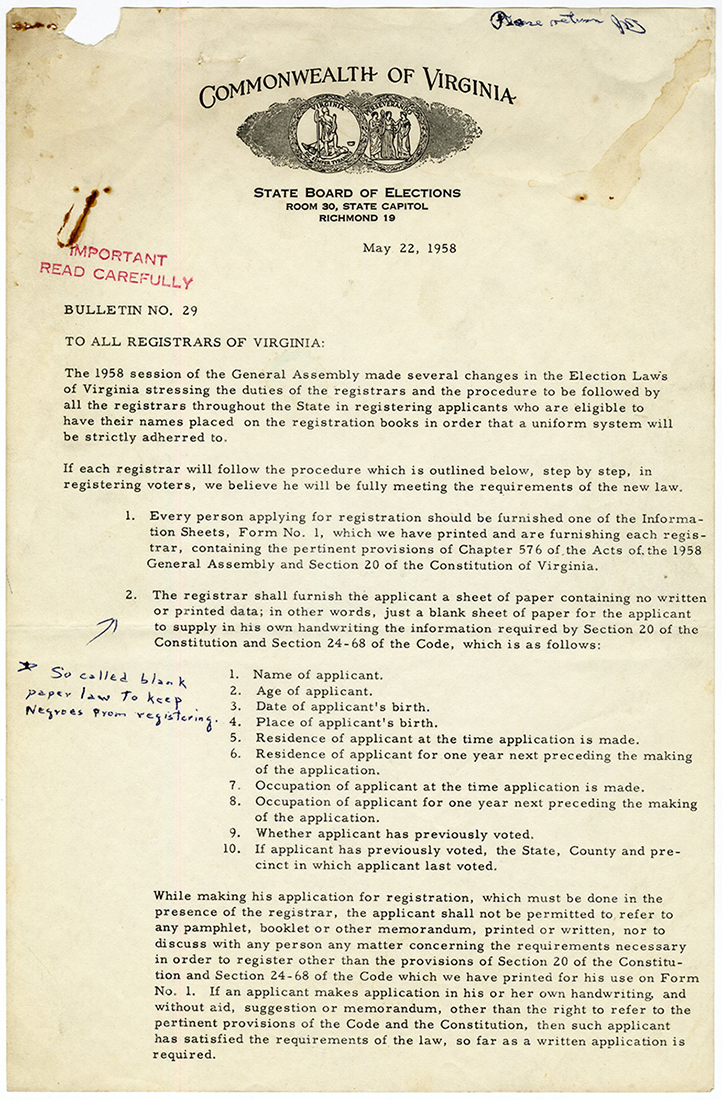

Poll taxes and the unequal application of literacy tests were effective tools for discrimination. Local offcials used the language in the 1902 constitution authorizing a "blank" form for registration to hand a literally blank piece of paper to applicants not expected to support the Democratic Party candidates. They had to fill out on the blank form the 10 required items from memory in order to qualify to vote.

Political leader W. Gordon Robertson said:7

the blank form was used by local officials to limit voter registration

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, Virginia State Board of Elections Bulletin No. 29

The political machine of Governor and then Senator Harry Byrd ensured the poll tax of his supporters was paid so they could vote. By the 1940's, Virginia's political process was considered to be so unrepresentative that the state was described as a "museum of democracy."8

The "Underwood" constitution adopted in 1870 had required the state's Supreme Court of Appeals to "hold its sessions at two or more places in the state, to be fixed by law." The General Assembly then specified that the court meet in Staunton, Winchester and Wytheville, as well as in Richmond. The 1902 constitution retained the requirement to meet in two or more places, but the General Assembly then decided that holding sessions in Winchester and Wytheville was not necessary.

The Supreme Court of Appeals met in Staunton and Richmond until the state constitution was revised again in 1971. The last meeting of the Supreme Court of Appeals in Staunton was in 1969.9

In Article IV, Section 44 of the 1902 Constitution, for the first time employees of the Federal government were specifically prohibited from serving in the General Assembly. Since 1868, only one Democrat had been elected president of the United States. Presidents appointed members of their party to Federal offices, and Federal officials hired members of their political party under the "spoils system." The 1902 provision blocked primarily Republicans from being elected to the state legislature:10

An attempt to revise the Bill of Rights in the 1902 constitution failed. One delegate proposed deleting the word "Christian" from the statement that "it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other."

The effort was intended to highlight that state government was completely neutral regarding religious beliefs; Jews in leadership positions should not be told to engage in a Christian practice. Though some other delegates were willing to alter the language, the constitutional convention retained the traditional wording in order to avoid stimulating a negative respons in the general populace to the 1902 constitution.

The 1901-1902 constitutional convention did respond favorably to pressure by Bapists and Methodists to block public funding on private institutions related to religious denominations. Cities such as Richmond and Norfolk were partnering with religious groups, including the Roman Catholic church, to operate charitable facilities such as homes for orphans and hospitals.

The Baptists and Methodists argued successfully that the institutions were not purely secular, and enhancing them would enhance the power and prestige of religious denominations. Much of the emotional component in their argument was fear of the Catholics.

The members of the convention were not logically consistent in their decisions. Banning public funding to non-public institutions was justified by the need to separate church and state, but the convention rejected a suggestion to incorporate and tax churches just like other businesses. The convention also expanded the property tax exemption on church property to include parsonages, which were provided primarily by rural Protestant denominations. State politics were still dominated by rural residents, while the small numbe of Roman Catholics were concentrated in the cities. 11

The 1902 constitution recognized the distinction between counties and independent cities. The new constitution also gave the governor more authority. That followed a pattern that started in 1830. It also created the State Corporation Commission, replacing the Board of Public Works. The State Corporation Commission was somewhat independent of the General Assembly, which was under the control of railroad lobbyists.

Article XV in the 1902 constitution made is easier to approve amendments. It modified the requirement created in the 1870 constitution that a proposed amendment had to be approved by a second General Assembly, after a general election for both houses, before submission to the voters for ratification. Instead, amendments could be approved at a second meeting of the General Assembly after an election for just the House of Delegates. Since delegates served two-year terms and state senators served four-year terms, the change in the 1902 constitution potentially accelerated approval of an amendment by two years.

Since 1902, no general constitutional convention has produced a document to replace - rather than amend - the 1902 constitution. The substantial amendments incorporated into the 1928 and the 1971 constitutions, other more-limited amendments, and the revisions proclaimed by limited constitutional conventions in 1945 and 1956 are all changes to (but not replacements of) the 1902 constitution.

voting registrars (including women after 1920) swore to uphold the 1902 state constitution that was ordained rather than ratified by voters

Source: Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, Found in the Archives (February 2020)