1776 Constitution of Virginia

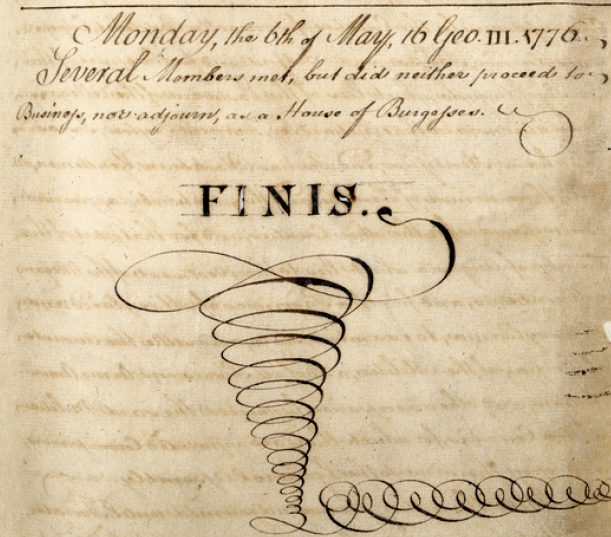

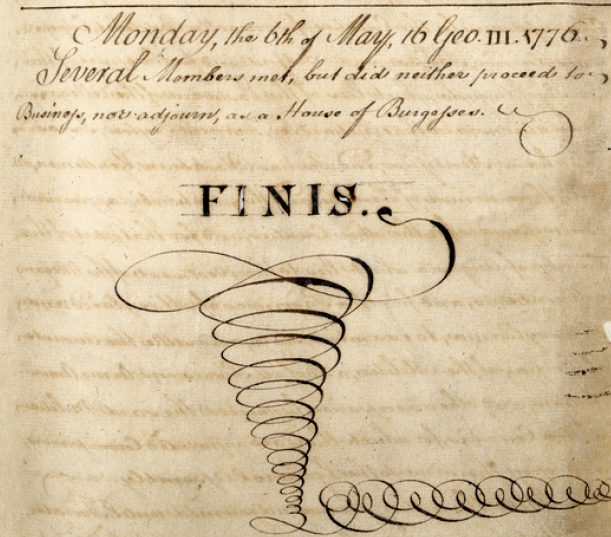

the colonial House of Burgesses stopped meeting on May 6, 1776, and the Virginia Revolutionary Convention declared independence and adopted the first state constitution a month later

Source: Library of Virginia, Final Meeting of the House of Burgesses ("Finis" Document), May 6, 1776

Three years before declaring independence, Virginia's gentry began to construct an alternative to the official colonial government led by Governor Dunmore. On March 12, 1773, Dabney Carr introduced a proposal in the House of Burgesses to create a standing Committee of Correspondence to build relationships with the disgruntled leaders in other colonies. That implemented an idea proposed back in 1768 Richard Henry Lee.

Similar to the committees created to unite the colonies in resistance to the Stamp Act in 1765, the 1773 committee was created without authorization from colonial governors. However, Virginia's 1773 committee was distinct because it was intended to be permanent. The supporters recognized that creation of committees in each colony would lead to a meeting, a "congress," of representatives from the colonies to propose joint actions of resistance.1

After 150 years of obedience to officials in London, the political leaders in Virginia began to create a new form of legitimate authority. Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke offered justifications for representative government without a monarchy and a Parliament, and but prior to the start of fighting in 1775 Virginians had little of the practical experience needed for creating an alternative.

After Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in May, 1774, 89 of the burgesses formed an extra-legal association to limit imports from Britain. The burgesses planned to stop buying anything imported by the East India Company, with the exception of saltpeter and spices for which there was no alternative source. The Virginia leaders also initiated calling of a "congress" with representatives of all the colonies to coordinate how they could deal with royal authority.

Further action was triggered a few days later by receipt of a letter from the Boston Committee of Correspondence. Massachusetts leaders proposed that the colonies stop trading with Britain, and apply the same economic leverage used to resist efforts by Parliament and King George III's officials to impose the Stamp Act and other new taxes in the 1760's.

Ending the import and export trade would dramatically impact the wealth of the Virginia colony. A ban on tobacco exports could bankrupt the very same people proposing that strategy, plus their family and neighbors. To consider next steps, 25 of the burgesses who had not left Williamsburg met at the Raleigh Tavern on May 30, 1774. The meeting was not authorized by the governor, of course.

As private citizens, acting on their initiative without instructions from the voters or permission from the governor, the burgesses proposed that each county should elect representatives to a "convention" in Virginia. The Royal Governor could prorogue and dissolve the House of Burgesses and refuse to call for elections to restart the colonial legislature. However, a convention could meet without the authority of Lord Dunmore.

The First Virginia Convention began on August 1, 1774. It met at the Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg, not in the Capitol building. The First Virginia Convention elected Virginia's representatives to the First Continental Congress. Four other conventions followed into 1776, providing a form of government for Virginia that paralleled and then replaced the House of Burgesses.

Some burgesses met in the Capitol on October 1775 and March 1776, but they adjourned without taking any action. To be official, a General Assembly meeting required the presence of the governor and Council of State. During the last two meetings of the House of Burgesses, Governor Dunmore was on a British warship in the Chesapeake Bay rather than in Williamsburg.

The final meeting of the House of Burgesses was on May 6, 1776, the first day of the Fifth Revolutionary Convention. In that final meeting the few burgesses in the room agreed to stop adjourning as the House of Burgesses, to stop anticipating it might be reconstituted rather than replaced. Instead, they decided that the House of Burgesses was "finis," which was the last word the assistant clerk of the House of Burgesses wrote in the official journal.2

When the 1773 Committee of Correspondence started, followed by the Association and five conventions, there was no roadmap to revolution or self-government for Virginia that omitted the authority of King George III and his royal governors. The people in the rooms during meetings of the Virginia Conventions and Continental Congresses had to invent new governmental structures and procedures for resolving conflicts and making decisions.

In 1775, Richard Henry Lee and John Adams began to explore how a new form of government could replace the colonial structures. The two men were in Philadelphia at the Continental Congress. They discussed how authority could be divided among executive, legislative, and judicial branches, reducing the excessive concentration of power that made colonial governors a threat to liberty.

Lee arranged to have an anonymous handbill published that shared his ideas, while Adams published his own Thoughts on Government. The proposals reassured reluctant revolutionaries that there would be continuity after independence, not chaos. Colonial authority could be replaced by state authority without a massive disruption of the decision process. A new form of government could be established, and Virginia would not be in a "state of nature" after declaring independence from Great Britain.

As portrayed by the philosopher Thomas Hobbs, only the rule of law kept naturally-selfish humans from raiding and attacking each other. Without a form of government to punish people who violated established rules of behavior, people in a state of nature rather than in a state of law would engage in constant warfare and life would be "nasty, brutish, and short."3

Virginia's Fifth Revolutionary Convention met in the Capitol at Williamsburg between May 6-July 5, 1776. On May 10, the Continental Congress called for the individual colonies to create new governments, starting the process towards establishing independence from Great Britain.

On May 15, 1776, the Fifth Revolutionary Convention delegates decided in a unanimous vote to instruct Richard Henry Lee and the other Virginia delegates at the Second Continental Congress to propose that all the colonies declare in a joint statement that they were now independent of Great Britain.

Also on May 15, 1776, the Fifth Revolutionary Convention appointed a committee:4

- "... to prepare a Declaration of Rights, and such a plan of Government as will be most likely to maintain peace and order in this Colony, and secure substantial and equal liberty to the people.

Richard Henry Lee proposed to the Second Continental Congress on June 7, 1776 that "these colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states" (Thomas Jefferson is wearing red vest)

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Declaration of Independence (painted by John Trumbull)

Virginia was not the first newly-independent state in North America to write a constitution. New Hampshire created one in January, while South Carolina adopted one in March 1776. Both were intended to be just temporary, rather than establish a lasting form of government independent from royal control.5

On May 10, 1776, the Continental Congress called for permanent replacement of royal government in all colonies. The Fifth Revolutionary Convention started to act before that news reached Richmond.

The convention members defined the structure of an independent state government, one that owed no allegiance to King George III. Those at the convention wanted a weaker chief executive than the royal governor and a stronger legislature than the House of Burgesses, but there were few models to imitate. Writing that first constitution to create a brand new government structure required creative thinking. Other colonies had the advantage of reacting to Virginia's example, and also chose to include a declaration of rights.

On May 15, 1776, the Fifth Revolutionary Convention passed a resolution that ultimately triggered the Declaration of Independence:6

- Resolved unanimously that the delegates appointed to represent this colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent states absolved from all allegiance to or dependence upon the crown or parliament of Great Britain... Provided that the power of forming government for and the regulations of the internal concerns of each colony be left to the respective colonial legislatures.

That required the convention, acting as a colonial legislature because the House of Burgesses was "Finis," to form a government that could create regulations to address the internal concerns of Virginia. The next resolution passed by the convention was to create committee to start that process:7

- Resolved unanimously that a Committee ought to prepare a Declaration of Rights and such a plan of government as will be most likely to maintain peace and order in this colony and secure substantial and equal liberty to the people.

A key drafter of the first Constitution of Virginia was George Mason IV, though many others were involved in preparing the final product. First Mason prepared the Virginia Declaration of Rights, in collaboration primarily with Thomas Ludwell Lee. Editorial changes proposed by Thomas Ludwell Lee were adopted without extensive discussion. Two policy changes made by the convention to Mason's draft of a Declaration of Rights were of great significance.

Debate over Mason's draft exposed the contradiction between the fight for liberty and the commitment of Virginia's elite to keep 40% of the population in slavery. The members of the convention were all white men, and they were not revolting against England in order to free the enslaved or to enfranchise women.

Mason's first draft, completed between May 20-26 1776, said in Article 1:8

- That all Men are born equally free and independant, and have certain inherent natural Rights, of which they can not by any Compact, deprive or divest their Posterity; among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty, with the Means of acquiring and possessing Property, and pursueing and obtaining Happiness and Safety.

Article 1 was amended by the Fifth Revolutionary Convention before ratification on June 12:9

- That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Virginia's wealthy slaveowners at the convention had no intention of treating all men as if they had "certain inherent natural Rights... among which are the Enjoyment of Life and Liberty." Independence was not intended to result in a new form of government in which black men would have an equal voice with white men, or to allow women equal rights.

Robert Carter Nicholas led the effort to narrow Mason's initial language and limit who could claim rights to life and liberty. Nicholas drew upon the philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, who described those living "in a state of nature," without a form of government, as being at great risk of living a "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short life." Enslaved people in Virginia lacked the ability to create laws and had to obey orders from their masters, so Nicholas claimed they were living in a state of nature.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and others proposed that government was a social contract, providing protection for people who choose to bond according to defined rules of behavior. A commitment to obey laws moved people out of a state of nature into a "state of society" where life, liberty, and property could be protected.

Robert Carter Nicholas ensured that the 1776 Declaration of Rights was based on the assumption that those who were enslaved lived in a state of nature, but that free white Virginians had entered into a state of society. Since the enslaved had not entered into a state of society, independence would not result in any increase of liberty for them.10

Other states relied upon Mason's initial draft of the Declaration of Rights when crafting language for their constitutions, as did Thomas Jefferson when he wrote the Declaration of Independence. Omitting the modifier "when they enter into a state of society" was significant in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in 1783 that slavery was inconsistent with the broad language included in that state's constitution.

When he was a Chancellor on a High Court of Chancery, George Wythe interpreted the Declaration of Rights in the 1776 Virginia Constitution in a manner similar to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Wythe ruled in Hudgins v. Wrights that Jackey Wright and her family members were free and not born into slavery as their enslaver, Houlder Hudgins, claimed.

The General Assembly had determined in 1662 that the status of the mother determined if a child was born free or could be enslaved for life. Enslaving Indians had been banned since 1705. Wythe accepted Jackey Wright's claim that her mother and grandmother were not enslaved, in part because she appeared physically to be of Native American and white ancestry with a copper complexion and straight hair.

Lawyers for Houlder Hudgins appealed to the Virginia Court of Appeals, the state's supreme court. They argued that the Wrights had a mixed ancestry involving black males. Wythe's judgement, that everyone was entitled to the presumption of free birth under the Declaration of Rights unless proven to be subject to enslavement, was upheld in 1806. However, the Court of Appeals narrowed Wythe's interpretation to apply to just white persons and Native Americans.

As a modern scholar described that decision:11

- Indians were by default citizens of a free nation; Africans were by default members of an enslaved race.

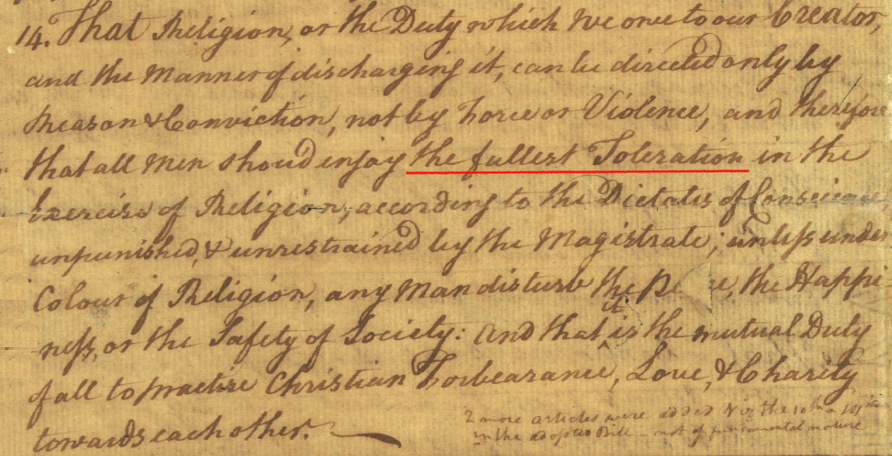

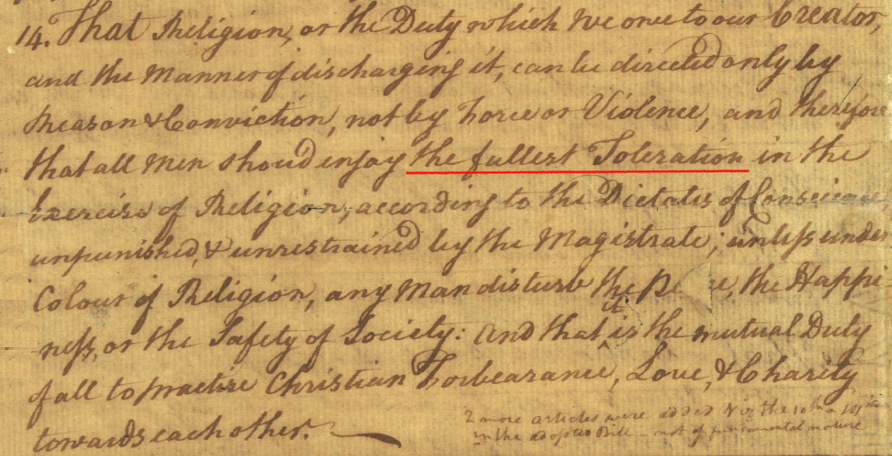

Another key revision was proposed by the youngest member of the convention. Though just 25 years old, James Madison spoke up and proposed changing Article 16.

Mason had proposed (emphasis added):12

- That as Religion, or the Duty which we owe to our divine and omnipotent Creator, and the Manner of discharging it, can be governed only by Reason and Conviction, not by Force or Violence; and therefore that all Men shou'd enjoy the fullest Toleration in the Exercise of Religion, according to the Dictates of Conscience, unpunished and unrestrained by the Magistrate, unless, under Colour of Religion, any Man disturb the Peace, the Happiness, or Safety of Society, or of Individuals. And that it is the mutual Duty of all, to practice Christian forbearance, Love and Charity towards Each other.

James Madison argued that religious belief was one of the natural rights that could not be ceded to government. Mason concurred, as did others at the convention, and in the final version Article 16 was changed to (emphasis added):13

- That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

The change from toleration to entitlement reduced the potential of the new Virginia government, in the future, to withdraw its permission for religious practices based on beliefs not held by the majority. Madison had experienced discrimination against Baptists in particular, and his edits added greater protection for Baptists, Presbyterians, Dunkards, and others who held minority religious views.

Madison was more ambitious in his efforts to establish religious freedom as a bedrock principle of natural rights. However, he failed to get approval of his proposed language that would have withdrawn state support for the established Anglican Church. The first constitution of Virginia excluded slaves, women, and Native Americans from direct participation in the political process. The 1776 constitution left the newly-independent state with an official, established church until passage of the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom in Virginia in 1786.

The governor was not designated as the head of the Anglican church in Virginia, to replace King George III in that position. Reflecting hostility to the Anglican ministers who had supported traditional royal authority rather than the revolution, and also an early indicator of the desire to separate church and state authority, ministers of the gospel were excluded from serving in the General Assembly or being appointed to the Council of State:14

- The two Houses of Assembly shall, by joint ballot, appoint Judges of the Supreme Court of Appeals, and General Court, Judges in Chancery, Judges of Admiralty, Secretary, and the

Attorney-General, to be commissioned by the Governor , and continue in office during good behaviour... These officers shall have fixed and adequate salaries, and, together with all others, holding lucrative offices, and all ministers of the gospel, of every denomination, be incapable of being elected members of either House of Assembly or the Privy Council.

George Mason proposed only toleration of religious minorities in his draft of a Declaration of Rights

Source: Library of Virginia, The Virginia Declaration of Rights, June 12, 1776

The Fifth Revolutionary Convention adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights on June 12, 1776.

While that convention debated the wording in the Declaration of Rights for several weeks, George Mason worked with a committee to draft a new state constitution. He presented his plan to the committee for debate and revision between June 8-10.

Mason had been able to draw on proposals made by John Adams in late 1775, then elaborated with more detail in January, 1776. Richard Henry Lee quickly had Adam's revised proposal published as a pamphlet entitled Thoughts on Government: Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies. In a Letter from a Gentleman to his Friend. It may have been Lee who had a proposal similar to that from John Adams published in Purdie's Virginia Gazette, on May 10, 1776.

Soon after publication of the John Adams proposal, an alternative was printed in Philadelphia. The "Braxton Plan" is attributed to Carter Braxton. His Address to the Convention of the Colony and Ancient Dominion of Virginia, on the Subject of Government in General, and Recommending a Particular Form to Their Consideration. By a Native of the Colony had little influence on George Mason or the convention. It was not published in Virginia until the June 8 and June 15 editions of Dixon & Hunter's Virginia Gazette. It

The Braxton Plan recommended an aristocratic approach with few changes to the royal form of government. However, the revolutionaries in Virginia's fifth convention were breaking from the past and they rejected the conservative approach of the Braxton Plan. The committee working with George Mason made significant changes to his draft, with almost every article being amended in some way.15

George Wythe brought a proposal from Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson produced three drafts while in Philadelphia in May, and sent the third draft with Wythe to carry south from Philadelphia. Jefferson separately sent another copy to Edmund Pendleton, to ensure delivery. It arrived as the committee was concluding its work. They were able to incorporate and expand on his list of grievances against King George III, but the convention did not reopen debate to address most proposals.

Jefferson had recommended that the royal governor be replaced with an "Administrator," elected by the legislature's "house of Representatives." To minimize the power of the executive branch, the Administrator would be allowed to serve only a one-year term and could not be re-appointed until three years had passed. The Administrator could not veto any bills, and could not dissolve, prorogue or adjourn either house of assembly.

11 years later in 1787, as delegates in Philadelphia drafted a replacement for the Articles of Confederation, Thomas Jefferson supported a weak role for any executive and empowering the elected legislators instead. In his lifetime royal governors had been the enemy and legislative assemblies had represented the people. To avoid creating the equivalent of a king, Virginia's new constitution should constrain the power of the new state's governor.

Jefferson wrote that, in his opinion, no monarch in Europe was qualified by merit even to serve on an Anglican vestry in Virginia:16

- There is scarcely an evil known in these countries which may not be traced to their king as its source...

The convention also ignored this provision in Jefferson's draft:17

- No person hereafter coming into this country shall be held within the same in slavery under any pretext whatever

Virginia's first state constitution was adopted on June 28, 1776. The Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, voted to declare independence on July 2. Only 12 colonies voted that day in support of the resolution proposed by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia:18

- Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

- That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

- That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation,

The New York delegates abstained because they had been instructed specifically not to vote for independence. The New York Provincial Congress reversed those instructions on July 9, allowing the Continental Congress to order on July 19 preparation of an "engrossed" version of the Declaration of Independence on parchment.

Two days later, the Continental Congress voted to issue a declaration publicly declaring the decision to separate from Great Britain, essentially a "press release" to announce and justify independence. The official paper record of the July 4 vote was signed by just the president and secretary of the Continental Congress, John Hancock and Charles Thomson.

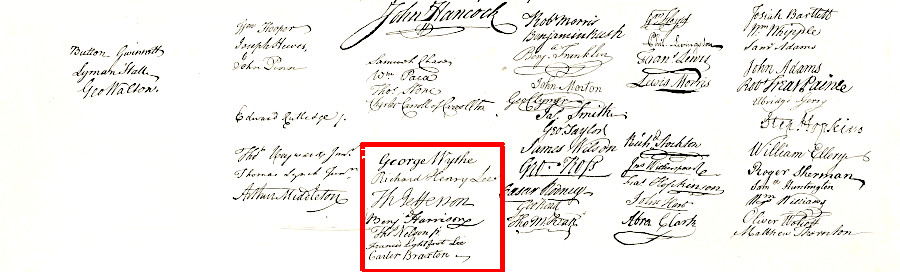

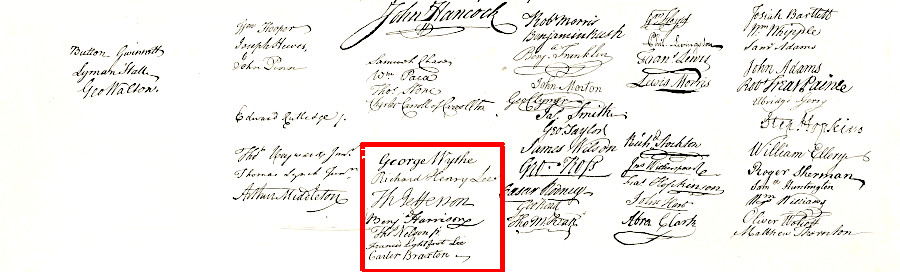

Signing of the parchment version of the Declaration of Independence started in Philadelphia on August 2, 1776. By the time John Hancock signed with his famous high-visibility flourish, Virginia was starting its second month of government under a state constitution.19

the seven Virginians who signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia could not participate in the Fifth Revolutionary Convention which adopted the first state constitution

Source: National Archives, America's Founding Documents

Virginia's Declaration of Rights had been appended to the state constitution; it did not require a second approval by the Fifth Revolutionary Convention. European philosophers had articulated concepts about liberty and how governments affected them, and other states had adopted temporary constitutions to replace colonial charters, but Virginia was the first of the 13 new states to adopt a new form of government intended to be permanent.

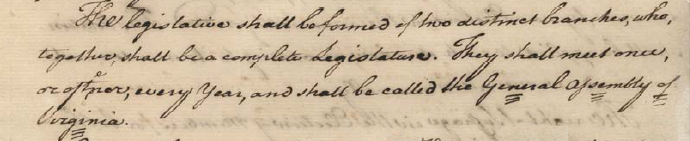

The government structure in the 1776 constitution included the House of Burgesses, though renamed to House of Delegates. The royal governor was replaced by a governor elected by the General Assembly, with far less power and a fixed one-year term (though he could be re-elected twice in a row). A new addition was the State Senate, with 24 districts drawn for electing members to that new body.

The Governor's Council, previously appointed by London officials, was replaced by an eight-member Council of State. Members of the Council of State, also called the Privy Council, were elected jointly by the State Senate and House of Delegates; the governor could not choose his own advisors. The convention intended to create a new form of government that would limit executive power. The governor's discretion was limited, and he was required to get advice from the Council of State before taking most actions. No "little king" in Virginia would replace George III in England:20

- Separation of powers was expressly asserted, but separation did not mean equality of power; the legislative branch was unquestionably dominant. This characteristic of legislative supremacy was an obvious expression of the revolt against executive authority from which the colonists had experienced abuses under the British Crown.

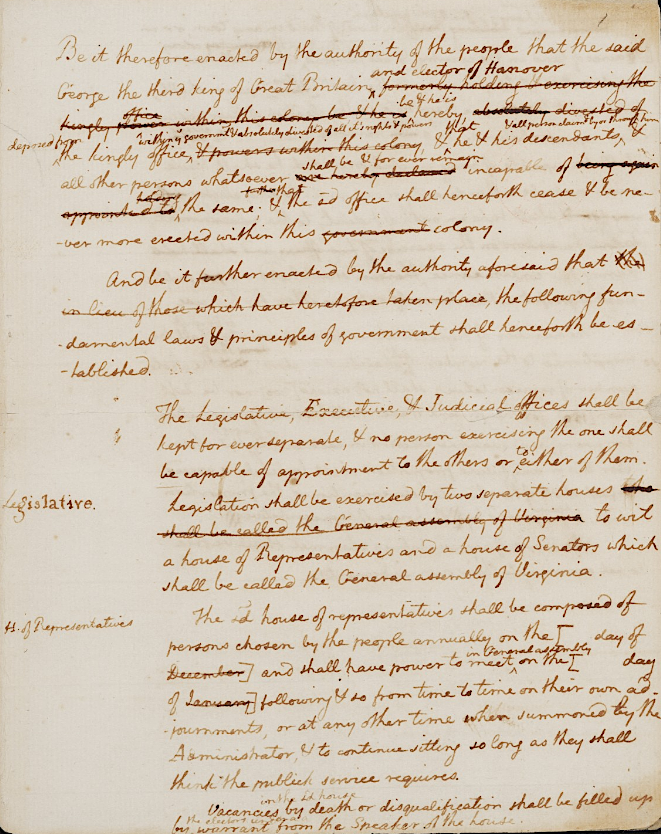

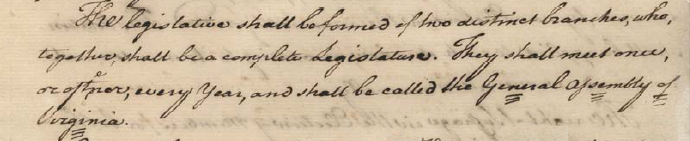

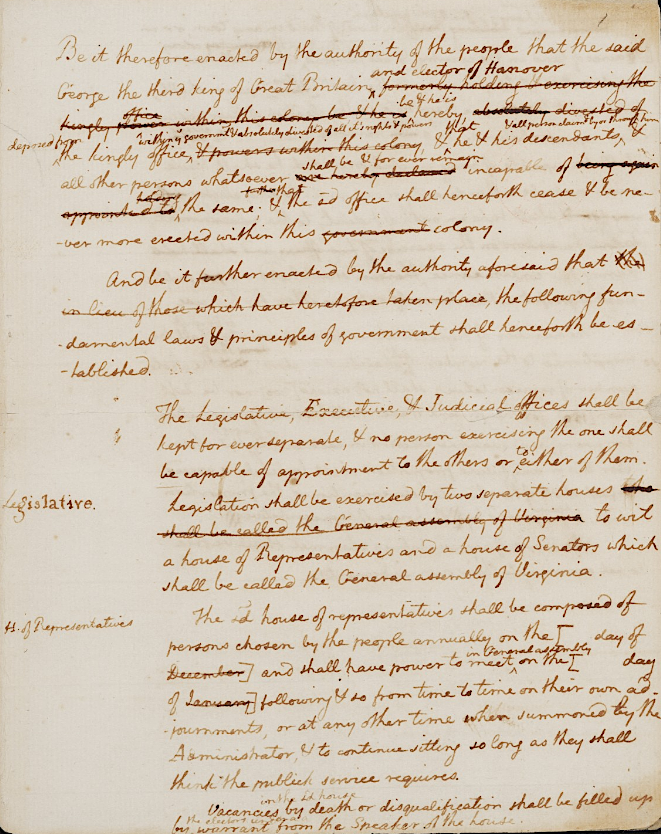

the first state constitution created the State Senate and defined the legislature as the General Assembly

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

The constitution designed the House of Delegates to have the greatest number of elected representatives with two for each of the 62 counties, two for the District of West Augusta, one for the city of Williamsburg, and one for the borough of Norfolk. The new State Senate was limited to just 24 members initially, and its political powers were constrained:21

- All laws shall originate in the House of Delegates, to be approved of or rejected by the Senate, or to be amended, with consent of the House of Delegates; except money-bills, which in no instance shall be altered by the Senate, but wholly approved or rejected.

The franchise, those authorized to vote in elections for government officials, was left unchanged in 1776. The requirements established in a 1736 law were continued; only male "freeholders" who owned a certain amount of property could participate in elections. The property requirement was ownership of:22

- ...fifty acres of land, if no settlement be made upon it, or twenty-five acres with a plantation and house thereon at least twelve feet square... and every person possessed of a lot in any city or town, established by act of Assembly, with a house thereon at least twelve feet square

Thomas Jefferson is often, but incorrectly credited with drafting Virginia's 1776 state constitution. He was in Philadelphia in 1776 as a member of the Second Continental Congress when the Fifth Revolutionary Convention drafted Virginia's first constitution. In contrast to Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee traveled to Richmond to participate in the May, 1776 discussions even though he was not a voting member of the Fifth Revolutionary Convention.

On May 16, 1776, Jefferson proposed the Virginia delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia return to Williamsburg to participate in the debate and decision process. He considered framing the new form of government for Virginia to be more important than serving in the Continental Congress. According to him, creating a good alternative to the royal form of government was:23

- ...the whole object of the present controversy; for should a bad government be instituted for us in future it had been as well to have accepted at first the bad one offered to us from beyond the water without the risk and expence of contest

Thomas Jefferson drafted a constitution for his home state of Virginia, but it arrived after the Fifth Revolutionary Convention was writing its own version

Source: US Capitol, https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/exhibitions/artifact/thomas-jeffersons-drafts-and-notes-virginia-constitution-june-1776

Jefferson was disappointed in the process used to create the 1776 state constitution, as well as the substance. He was concerned that a constitution approved only by the legislature would not constrain the legislature's power, if the constitution could be treated as a regular law and modified at will. Jefferson wanted the constitution to be ratified by a vote of the people, to become fundamental law that could be modified only by another vote of the people. Otherwise, the General Assembly might pass legislation which infringed on the natural rights of the citizens. A serious concern was that freedom of religion could be constrained by the re-establishment of an official state-supported church, unless a fundamental law blocked the legislature from such action.

When Jefferson sent his proposed constitution from Philadelphia to Richmond in June, 1776, he included a note:24

- It is proposed that this bill, after correction by the Convention, shall be referred by them to the people to be assembled in their respective counties and that the suffrages of two thirds of the counties shall be requisite to establish it.

The 1776 Virginia constitution established the first government with separate offices responsible for executive, legislative, and judicial responsibilities. Separation of government, with checks-and-balances by different branches, was an unproven approach. Thomas Jefferson objected to the excessive power granted to the legislature. The governor was elected by the General Assembly and had no veto power. The power of judges, operating in an independent branch separate from the legislature and executive for the first time, was not clear. Implementation of the concept of judicial review had not been established yet. Though the power of the royal governor had been dispersed in the 1776 constitution, Jefferson feared the power concentrated in the legislative branch could evolve into "elective despotism."

The General Assembly and the Council of State chose to defer to the 1776 constitution, rather than modify or ignore it. George Wythe quicky claimed that a Virginia court could treat the constitution as fundamental law and void an act passed by the legislature that was inconsistent with it. In 1782, in Commonwealth v. Caton, Wythe declared boldly that the Supreme Court of Appeals was empowered and he was prepared to block the legislature from overstepping the limited powers granted to it by the people in the state constitution. His clear statement was issued 21 years before the Marbury v. Madison case, in which Chief Justice John Marshall declared that the US Supreme Court had the right to void laws passed by the new US Congress that began meeting in 1789.25

Jefferson returned to from Philadelphia to Virginia in 1776. Though too late to shape the state's constitution, he sought to revamp the laws passed by the General Assembly when Virginia was a royal colony. Jefferson served on a Committee of Revisors with Edmund Pendleton and George Wythe, a group tasked by the General Assembly to propose reforms to all the existing laws, updating them to reflect principles of republican government. Jefferson was especially interested in altering the aristocratic procedures that directed inheritances to the oldest son ("primogeniture") and prevented the division and sale of land ("entail").

The reformation process was slow, and it was not until 1779 that the three men documented 126 laws that needed to be changed. Jefferson was active during those three years in proposing changes to individual laws whenever he saw that he might get a majority of votes to address a particular issue.2526

As British and Patriot armies were fighting the American Revolution and independence was still at risk, the General Assembly was willing to revise old laws in a piecemeal fashion but was not inclined to revise the 1776 state constitution. After the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, Jefferson thought the legislature might be willing to hold a constitutional convention. To ensure his ideas were considered, he spent only a month in drafting a constitution to recommend for adoption.

In his 1776 draft of a constitution, Jefferson based his language on his experience in court dealing with colonial laws and procedures, reactions to the problems with royal government, and theoretical proposals and concerns regarding "republican" government. By 1783, practical experience provided him new perspective, and he modified his 1776 language.

For example, Jefferson had been governor in 1781 when Lord Cornwallis forced him and the General Assembly to flee Richmond. The weak powers assigned to the governor left him unable to respond appropriately, and he resented the way he was blamed for the failed response by the Virginia militia to Cornwallis' invasion. The 1783 draft proposed that the governor have greater responsibility over the state militia. The draft also strengthened the executive branch by extending the term of the governor from one year to five years, and reducing the Council of State to a mere advisory body.

Though Jefferson did not propose giving the governor the power to veto laws, he did propose creating a Council of Revision that could alter legislation passed by the General Assembly. The Council would be composed of the Governor, Chancellor, and judges of the Supreme Court of Appeals, so the separation of executive, legislative and judicial powers would have been blurred.

When the US Constitution was passed, John Adams viewed the three branches of government at the state level as the governor, senate, and assembly. That structure was a parallel to the colonial system of a King, Houe f Commons, and House of Lords. It reflected the perspective of the elite that society consisted of preeminent figures, nobles, and commoners. Adams opposed proposals to unite in unicameral legislatures the elected assembly and the appointed senate.

Today all high school civics classes teach that in the United States, government authority is divided between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches; each branch serves as a check-and-balance on the other two. That concept evolved only after Chief Justice John Marshall made rulings, particularly in the 1803 Marbury v. Madison case, that established the power of the courts to void laws which judges determined to be unconstitutional.

Jefferson's proposed 1783 constitution sought to modify the election districts so Tidewater planters were not given excessive influence in the House of Delegates. He also proposed abolishing the slave trade and starting gradual emancipation of enslaved people, declaring to be free all those born after December 31, 1800. The right to vote was broadened to "free male citizens of full age and sane mind" who had lived within a county for a year, or had been enrolled in the militia for a year, or had owned a certain amount of property there.

Jefferson sent his 1783 draft to James Madison, who was serving in the General Assembly. Patrick Henry successfully resisted the agitation for a constitutional convention, so the merits and shortcomings of the 1776 Constitution and Jefferson's 1783 draft were not debated in a public forum. Instead, Jefferson published his draft as an appendix to Notes on the State of Virginia. It was available to those drafting the US Constitution in 1787 and the state constitution for Kentucky in 1792, but was just one of many resources by then.27

Though Patrick Henry blocked efforts to get a new constitution adopted in 1783, James Madison led an initiative in the General Assembly in 1785 to revise the laws of Virginia to incorporate some of Jefferson's ideas. Madison started with the package of 126 reformed laws proposed in 1779 by the Committee of Revisors. He manage to get about one-third of the laws passed in 1785-86, even though much of his energy was directed towards approval of the controversial Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.28

The 1776 constitution lacked any provision for amendment. It was in effect for 54 years until replaced with a new state constitution.

Efforts to alter the 1776 version came primarily from people living west of the Fall Line, and especially west of the Blue Ridge. They were under-represented, while eastern counties had an excessive number of delegates and state senators who prioritized the concerns of the Tidewater gentry.

Legislators finally called for Virginia's first convention dedicated to writing a constitution only as the 1830 Census prepared to reveal the regional imbalance in representation. It was not until 1851, 77 years after adoption of the 1776 constitution, that the right to vote was broadened significantly beyond those owning land or that the western counties achieved significantly more representation in the General Assembly.29

Links

- 1776 Constitution of Virginia

- Constitution Project

- Current Constitution

- Library of Virginia

- The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and other Organic Laws of the States and Territories now or heretofore forming the United States of America (compiled and edited by Francis Newton Thorpe, 1909)

- Thomas Jefferson: Notes on the State of Virginia

References

1. "Thomas Jefferson to Dabney Carr, 19 January 1816," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-09-02-0238; Edgar Wallace, "Dabney Carr," The Louisa County Historical Magazine, Volume 2, Number 2 (December, 1970), pp.11-12, http://www.piedmontvahistory.org/archives14/files/original/f627c7efa0510327942350d5f1c4ffed.pdf (last checked March 10, 2021)

2. "Resolution to Summon a Convention in Williamsburg, May 30, 1774," Library of Virginia, http://edu.lva.virginia.gov/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/doc/resolution_1774; "Raleigh Tavern," Colonial Williamsburg, https://www.history.org/almanack/places/hb/hbral.cfm; "Final Meeting of the House of Burgesses ('Finis' Document), May 6, 1776," Library of Virginia, http://edu.lva.virginia.gov/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/doc/finis (last checked February 5, 2019)

3. John E. Selby, "Richard Henry Lee, John Adams, and the Virginia Constitution of 1776," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 84, Number 4 (October, 1976), https://www.jstor.org/stable/4248066; "Thomas Hobbes: Leviathan," Online Library of Liberty, October 31, 2023, https://oll.libertyfund.org/publications/reading-room/2023-10-31-temnick-thomas-hobbes-leviathan (last checked July 31, 2025)

4. "Preamble and Resolution of the Virginia Convention, May 15, 1776," The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/const02.asp; Ray Raphael, "10 Myths For The Fourth Of July," Journal of the American Revolution, July 1, 2014, https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/07/10-myths-for-the-fourth-of-july/ (last checked July 4, 2023)

5. "Constitution of South Carolina - March 26, 1776," The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/sc01.asp; "Constitution of New Hampshire - 1776," he Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/nh09.asp; Colin Bonwick, "Enlightenment and Experience: The Virginia Constitution of 1776" in G. L. McDowell et al. (editors), America and Enlightenment Constitutionalism, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p.179, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057/9780230601062_8.pdf (last checked March 14, 2021)

6. "This Day in Virginia History - May 15, 1776," Library of Virginia, https://www.virginiamemory.com/reading_room/this_day_in_virginia_history/may/15 (last checked March 14, 2021)

7. "This Day in Virginia History - May 15, 1776," Library of Virginia, https://www.virginiamemory.com/reading_room/this_day_in_virginia_history/may/15 (last checked March 14, 2021)

8. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights - First Draft," Gunston Hall, https://gunstonhall.org/learn/george-mason/virginia-declaration-of-rights/virginia-declaration-of-rights-first-draft/ (last checked March 14, 2021)

9. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights - Ratified Version," Gunston Hall, https://gunstonhall.org/learn/george-mason/virginia-declaration-of-rights/the-virginia-declaration-of-rights-ratified-version/ (last checked March 14, 2021)

10. "Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau on Government," Bill of Rights in Action, Constitutional Rights Foundation, Spring 2004, https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-20-2-c-hobbes-locke-montesquieu-and-rousseau-on-government.html; "Virginia Declaration of Rights by George Mason," Constituting America, March 13, 2013. https://constitutingamerica.org/wednesday-march-13-2013-essay-18-virginia-declaration-of-rights-by-george-mason-guest-essayist-kevin-r-c-gutzman-j-d-ph-d-professor-and-director-of-graduate-studies-department-of-histo/; Jeff Broadwater, "George Mason (1725-1792)," Encyclopedia Virginia, March 6 2014, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Mason_George_1725-1792; Kevin Gutzman, Virginia's American Revolution: From Dominion to Republic, 1776-1840, Lexington Books, 2007, p.28, https://books.google.com/books?id=w9xvrrB6LckC (last checked March 14, 2021)

11. Randy E. Barnett, "Opinion: What the Declaration of Independence Said and Meant," Washington Post, July 4, 2017 , https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/07/04/what-the-declaration-of-independence-said-and-meant/; Vernellia Randall, "Hudgins v. Wrights (1806)," Race and Racism in American Law, Dayton Law School, University of Dayton, 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20150706225511/http://academic.udayton.edu/legaled/Race/Cases/Hudgins%20v%20Wrights.htm; "Hudgins v. Wrights," Wythepedia, College of William and Mary, https://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Hudgins_v._Wrights; Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won't Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America, Harvard University Press, 2010, p.24, https://www.google.com/books/edition/What_Blood_Won_t_Tell/TV4lEAAAQBAJ (last checked September 4, 2023)

12. "George Mason and the American Revolution," Gunston Hall, https://gunstonhall.org/category/virginia-declaration-of-rights/ (last checked March 14, 2021)

13. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights – Ratified Version," Gunston Hall, https://gunstonhall.org/learn/george-mason/virginia-declaration-of-rights/the-virginia-declaration-of-rights-ratified-version/ (last checked March 14, 2021)

14. "The Virginia Declaration of Rights," (Mason's initial draft), Gunston Hall, http://www.gunstonhall.org/georgemason/human_rights/vdr_first_draft.html; Constitution of Virginia, June 29, 1776, posted online by National Humanities Institute, http://www.nhinet.org/ccs/docs/va-1776.htm; Robert A. Rutland, James Madison: The Founding Father, MacMillan, 1987, p.11, https://books.google.com/books?id=iHpfjCoA1_wC; "Virginia Constitution, 1776," for Virginians: Government Matters, https://vagovernmentmatters.org/files/download/419/fullsize.pdf (last checked December 4, 2015)

15. "Editorial Note: The Virginia Constitution," in Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0161-0001; Brent Tarter, "George Mason and the Conservation of Liberty," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 99, Number 3 (July, 1991), https://www.jstor.org/stable/4249228; "George Mason and the American Revolution," Gunston Hall, https://gunstonhall.org/category/virginia-declaration-of-rights/ (last checked March 14, 2021)

16. "'Shall We Have a King?'," American Heritage, Volume 70, Number 4 (Fall 2025), https://www.americanheritage.com/shall-we-have-king (last checked October 19, 2025)

17. "III. Third Draft by Jefferson, [before June 1776]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0161-0004 (last checked March 14, 2021)

18. "Lee Resolution (1776)," National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/lee-resolution (last checked July 4, 2023)

19. Ray Raphael, "Was The Declaration of Independence Signed On July 4? How Memory Plays Tricks With History," Journal of the American Revolution, July 4, 2023, https://allthingsliberty.com/2023/07/declaration-independence-signed-july-4-memory-plays-tricks-history/ (last checked July 4, 2023)

20. Brent Tartar, The Grandeees of Government: the Origins and Persistence of Undemocratic Politics in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2013, p.76, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Grandees_of_Government/cedrAAAAQBAJ; Albert L. Sturm, "The Constitution of Virginia: 1776 and 1976," University of Virginia Newsletter, Volume 53, Number 4 (December 1976), p.13, https://newsletter.coopercenter.org/sites/newsletter/files/Virginia_News_Letter_1976_Vol._53_No._4.pdf (last checked June 12, 2021)

21. "The Constitution of Virginia (1776)," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/the-constitution-of-virginia-1776/ (last checked August 16, 2023)

22. Julius F. Prufer, "The Franchise in Virginia from Jefferson through the Convention of 1829," The William and Mary Quarterly, Volume 7, Number 4 (October, 1927), p.255, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1921255; "Virginia State Constitutions 1776-1971," Library of Virginia, 2021, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/71constitution/resources/Virginia-Constitutional-History.pdf (last checked June 23, 2021)

23. "Editorial Note: The Virginia Constitution," in Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0161-0001; "Virginia's Fifth Revolutionary Convention Called for Independence," This Day in History, Library of Virginia, http://www.virginiamemory.com/reading_room/this_day_in_virginia_history/may/15; "'One of the most intriguing might-have-beens in American History' - Jefferson's Tardy Constitution," Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2007, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Spring07/jefferson.cfm (last checked March 10, 2021)

24. "III. Third Draft by Jefferson, [before June 1776]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0161-0004 (last checked March 14, 2021)

25. "Commonwealth v. Caton," Wythepedia blog, William and Mary Law Library, http://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Commonwealth_v._Caton; "Commonwealth V. Caton 4 Call's (Va.) Reports (1782)," Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/politics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/commonwealth-v-caton-4-calls-va-reports-1782; "Editorial Note: Jefferson's Proposed Revision of the Virginia Constitution," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0255-0001 (last checked March 10, 2021)

26. "Report of the Committee of Revisors Appointed by the General Assembly of Virginia in MDCCLXXVI," Wythepedia, William and Mary Law Library, https://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Report_of_the_Committee_of_Revisors; "Editorial Note: Revisal of the Laws 1776-1786," Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0132-0001 (last checked March 12, 2021)

27. "III. Jefferson's Draft of a Constitution for Virginia, [May-June 1783]," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0255-0004; "Editorial Note: Jefferson's Proposed Revision of the Virginia Constitution," Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0255-0001; Robert Forbes, "Notes on the State of Virginia (1785)," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, January 12, 2021, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/notes-on-the-state-of-virginia-1785/; "Left Behind In History: John Adams' Misguided Defense," Journal of the American Revolution, November 9, 2023, https://allthingsliberty.com/2023/11/left-behind-in-history-john-adams-misguided-defense/ (last checked November 9, 2023)

28. "Editorial Note: Revisal of the Laws 1776-1786," Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0132-0001 (last checked March 4, 2021)

29. Albert L. Sturm, "The Constitution of Virginia: 1776 and 1976," University of Virginia Newsletter, Volume 53, Number 4 (December 1976), p.14, https://newsletter.coopercenter.org/sites/newsletter/files/Virginia_News_Letter_1976_Vol._53_No._4.pdf (last checked June 12, 2021)

Virginia Government and Politics

Virginia Places