the drafters of the US Constitution within Independence Hall in Philadelphia in 1787 could take advantage of the 13 state constitutions, starting with Virginia's written in 1776

Source: National Park Service, Independence Hall

the drafters of the US Constitution within Independence Hall in Philadelphia in 1787 could take advantage of the 13 state constitutions, starting with Virginia's written in 1776

Source: National Park Service, Independence Hall

Leaders in each of the 13 British colonies paid attention to events in the other 12 colonies, but until the 1760's declined to work in concert. In London, officials sought for consistent policies between individual colonies and Native American tribes, but trade rivalries caused colonies to negotiate separately and undercut each other's bargaining positions.

All colonies were ordered to send representatives to a conference in Albany, New York in 1754 to rationalize dealings and craft a treaty with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederation. Seven colonies ended up appearing, but none south of Maryland sent representatives to the Albany Conference.

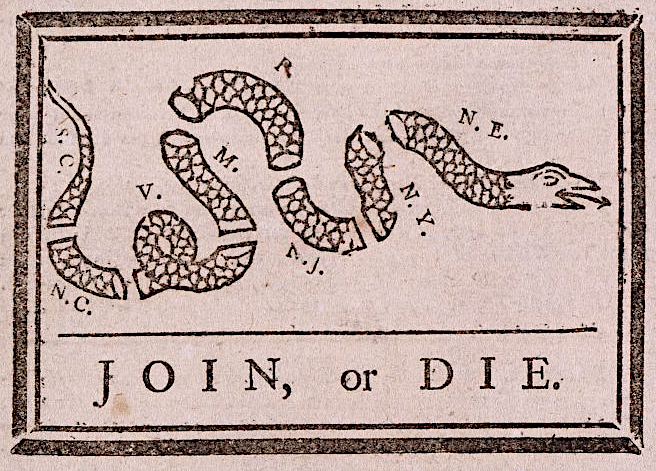

Benjamin Franklin pushed for coordinated action and voluntary union by the colonies, exemplified by his Join or Die cartoon. However, centralizing the colonial governments would increase the power of officials who reported to London while reducing the authority of elected representatives in separate colonial legislatures.

At the Albany Conference, attendees did adopt a proposed plan of union on July 10, 1754. After representatives returned to their individual colonies, however, no actions were taken to implement the unification plan even after the destruction of General William Braddock's army in 1755.

The Albany plan of union involved centralizing negotiations with Native American tribes and resolving boundaries between colonies claiming the same land:1

no Virginia representative attended the 1754 Albany Conference

Source: Library of Congress, Join or Die (Benjamin Franklin, 1754)

No Virginians attended the Albany Conference in 1754, though they did attend various treaty negotiations involving other colonies and Native America tribes in New York and Pennsylvania over the next two decades. The separate colonies failed to unite in 1754; their rivalries were more important. British officials determined policies and military strategies during the French and American War, and there was no coordinated approach by the colonial legislatures for dealing with Native Americans in particular.

The Proclamation of 1763, the Stamp Act and Sugar Act in 1765, and then the Intolerable Acts after the Boston Tea Party triggered a change in perspective.

A reliable Virginia commitment to coordinate policies and actions with all other colonies started with the creation of Committees of Correspondence during the response to the 1765 Stamp Act. Boycotts and other economic sanctions by the colonies had to be synchronized in order for non-violent action to have enough impact in Great Britain to force Parliament to change policies.

The critical driver to create a political union among all the colonies was the need for coordinated and centralized military capacity during the American Revolution. State constitutions replaced colonial charters starting a year after fighting erupted at Lexington and Concord.

Richard Henry Lee presented the resolution from Virginia on June 7, 1776 to declare independence. The Continental Congress decided on June 11, 1776 to appointed two committees. One was assigned the task of drafting a declaration to establish independence, while the other committee was given the responsibility of determining how the colonies should join together in some form of common government.

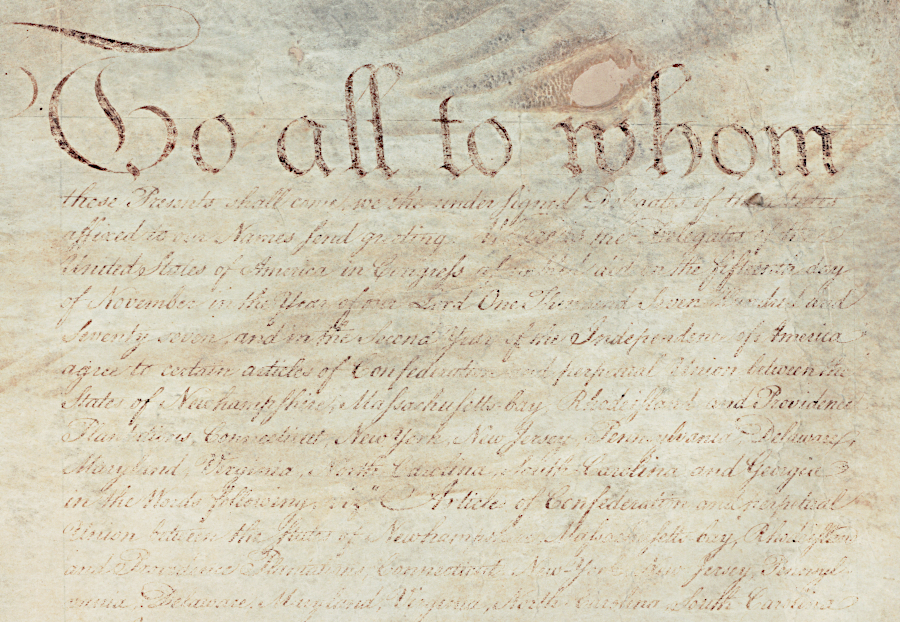

Thomas Jefferson took the lead in the first committee and prepared the Declaration of Independence. It was approved officially on July 4, 1776. John Dickenson took the lead to draft what became the Articles of Confederation, and the final version was approved by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777.

Each of the states was given equal representation in the national government of the new United States of America, despite the major differences between them in size and population. To go into effect, all 13 states had to ratify the Articles of Confederation. Canada was specifically invited to join as well. The document ensured that the states would empower the national government to prosecute the war, and no state would sign a separate peace treaty with Great Britain. Any future amendment to the document required approval by all 13 states.

The first state to ratify the Articles of Confederation was Virginia, on December 16, 1777. All but three other states ratified before June, 1778. The holdouts were Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey. They had no claims to western land claims, and wanted the status of those claims by other states to be resolved first.

New Jersey finally ratified on November 20, 1778. Delaware followed on February 1, 1779. It was still unclear then if Great Britain would win a military victory and suppress the rebellion, returning the states to the status of colonies.

Virginia relinquished its western land claims to the national government, and identified its conditions for eventual cession of the Northwest Territory, on January 2, 1781. That was sufficient for Maryland's legislators, and its General Assembly finally ratified the Articles of Confederation on March 1, 1781.2

the first words of the Articles of Confederation are "To all to whom these Presents shall come..."

Source: National Archives, Articles of Confederation (1777)

Some of the Virginians who prepared the first state constitution in 1776 during the Fifth Revolutionary Convention in Williamsburg were key participants in another convention a decade later. It met 11 years later in Philadelphia to prepare a constitution that would define a new relationship between the states.

The national government was not operating successfully under the Articles of Confederation. Those had been adopted by the Second Continental Congress in 1777, after revision and debate over six drafts. The Articles of Confederation were finally ratified by the last state (Maryland) on March 1, 1781.

Five years later, it was clear that Congress was unable to make the decisions necessary to keep the United States "united enough" to defend itself against European rivals, or to facilitate trade and economic development within the country.

Virginia and Maryland had negotiated a compact in 1785 for free trade across the Potomac River, after George Washington hosted the Mount Vernon Convention. Trade between the other states was constrained by various fees, tariffs, and other barriers. Economic recession in 1785 was followed by Shays' Rebellion in 1786 in Massachusetts, as western farmers resisted state-imposed taxes.

The negotiations at Mount Vernon led to the Annapolis Convention in September, 1786, to which New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia sent representatives. They focused on the commercial disputes between the states, and how to restructure interstate relations. In the end, they called for another convention of all the states, to start in Philadelphia.

As Thomas Jefferson later described the challenge faced by political leaders:3

Representatives from 12 of the not-so-united 13 states met in Philadelphia in 1787 to define a new relationship among the states. What is known today as the Constitutional Convention was held to form a "more perfect union." What the delegates prepared was ratified by 11 states in 1788, and then by North Carolina and Rhode Island over the following two years.

The Articles of Declaration, crafted in the early stages of the American Revolution, have largely been forgotten. The Federal Constitution has achieved mythic status now. A shrine has been created at the National Archives for visitors to see the document in an altar-like setting.

That reverence would surprise the men who negotiated it in 1787, or argued for its adoption by the 13 colonies in 1788-90. The US Constitution is a powerfully influential document today, but in 1787 it was just a negotiated agreement between people seeking to re-arrange a failed "first marriage" managed under the Articles of Confederation. The five states who attended the Annapolis Convention in 1786 recognized that they could not overcome interstate trade barriers constraining economic development within the United States. The convention's main result was a call for commissioners from all the states to:4

The Virginia General Assembly was the first to appoint commissioners to the proposed meeting. Six other states followed that example before the Continental Congress proposed a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation.

George Washington debated whether he should attend the meeting in Philadelphia. In response to Washington's request for advice, Henry Knox wrote:5

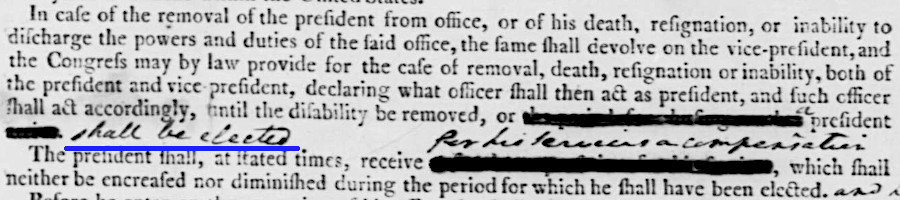

marginal notes made by George Washington during debates on a draft of the US Constitution, suggesting a different way of replacing a president

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Constitution, Printed, with Marginal Notes by George Washington, September 12, 1787

Delegates to the convention in Philadelphia had the advantage of reading 13 previous efforts to define how people were willing to govern themselves through democratic institutions, starting with the first constitution adopted in 1776 in Virginia. One lesson learned after 11 years from governing under Virginia's first constitution was the need to include a process for amendments. Virginia's constitution required a new convention to write a new constitution after changing circumstances required revisions, a step that did not occur until 1830.

Crafting the new "marriage agreement" between the colonies required substantial compromises. Virginia's delegates proposed a new government structure, the Virginia Plan, where representation in two legislative branches would be based on the number of free inhabitants. As the state with the largest population, Virginia would have the greatest voice in such a government.

New Jersey countered with a proposal that each state get a single vote in a one-chamber (unicameral) legislature, similar to the decision process under the Articles of Confederation. The Connecticut Compromise created the bicameral US Congress in which representation in the House of Representatives is based on population, while each state gets two votes in the Senate. In the Electoral College for selection of a president, every state got two votes based on having two members in the US Senate plus additional votes equal to the number of members from that state in the US House of Representatives.

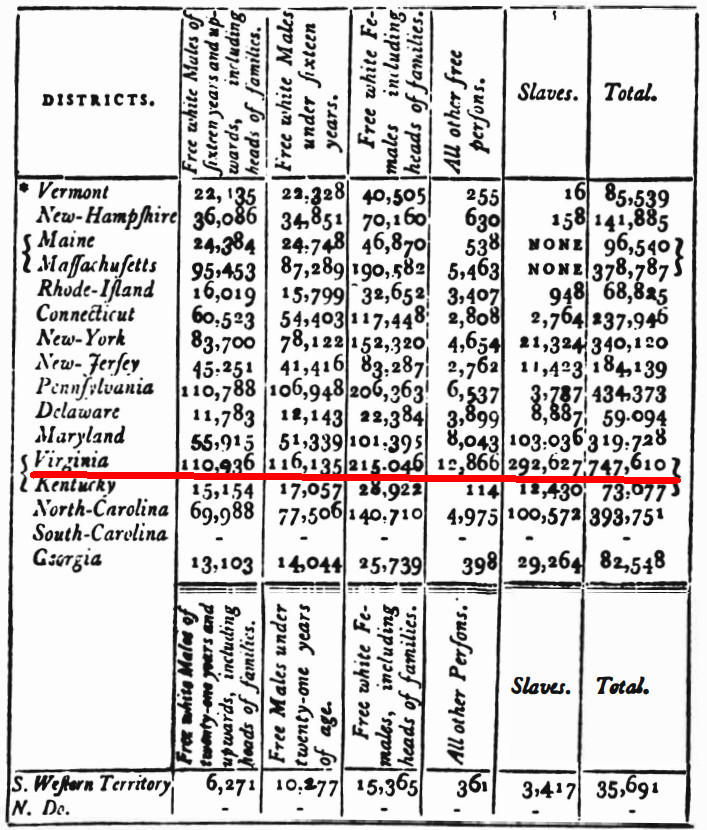

The political leaders of Southern states, already dependent upon the institution of slavery, insisted upon ensuring that Northern states would not restrict it. One of many compromises made at the Philadelphia Convention was to increase the number of votes in the US House of Representatives of Southern States. Proposals to the number of US Representatives on the free (almost entirely white) population were revised to include a percentage of the enslaved (all black) population as well.

Since Southern states had the largest number of enslaved people, the decision to count some of them increased the political power of those states in the US House of Representatives and the Electoral College. All tax bills has to be originated in the House of Representatives, so the compromise that led to counting some of the enslaved population gave Southern states the power to block direct taxes that would limit the value of slave "property."

The Philadelphia Convention could have decided to count 100% of the population in the different states when determining how to allocate votes in the US House of Representatives. From the perspective of New York, Massachusetts, and other Northern states, such percentage would have granted too much power to the Southern states where the enslaved population was concentrated.

The non-free population, including "Indians not taxed", could not vote; they were not allowed to participate in the democratic decision process within the states. Counting people who could not vote did not ensure that elected officials would represent the popular will, but that was not the priority in the debate. After all, the concept of giving white women or children the right to vote was not seriously considered.

The fundamental issue behind the debate about counting the enslaved population was allocating political power between different regions in the new country. In 1787 the Northern and Southern states sought to find a balance that would allow them to increase the strength of a united government. The alternative was clear - the states would eventually split into separate fragmented groups, similar to how Europe was organized into separate nations that engaged in almost constant destructive wars.

The representatives of the 12 states that participated in the Philadelphia convention decided to give the Southern states a 60% bonus in the House of Representatives by counting three-fifths of the enslaved population. That percentage did not reflect a perspective that enslaved people were only 60% human; the three-fifths percentage was a compromise over political power and not a debate about humanity.

In the end, the US Constitution included in Article I, Section 2:6

Virginia benefitted more than any other state by the decision to count three-fifths of enslaved people for representation in the new Federal government

Source: Census Bureau, Return of the Whole Number of Persons within the Several Districts of the United States (1790)

George Washington had presided over the discussions while sitting in a chair with a sun symbol on it. Benjamin Franklin commented at the end of the debate:7

a replica of the "rising" sun on George Washington's chair at the 1787 Constitutional Convention

The document proposed by the convention in Philadelphia granted too much authority to the Federal government, at least as some interpreted it. Debates during the 1788 ratification process in Virginia centered on whether a second constitutional convention would be required to revise the 1787 version. In Virginia, Patrick Henry led the opposition that sought to block ratification of the proposed constitution. He proposed that new amendments be developed and incorporated first, before ratification by Virginia's voters later.

Opponents of the proposed Federal government, including George Mason, feared the new central government would assume powers that infringed on individual liberty and state's rights. Reflecting his concern that a new national government would expand beyond the limited authorities granted by the constitution drafted in Philadelphia, Patrick Henry said "I smelt a rat."

Source: George Washington's Mount Vernon, Jefferson and Hamilton Debate Federal vs. States' Rights

The Virginia ratification convention met June 2-27, 1788. Delegates assembled on Broad Street in the Richmond Theatre, which was serving as the state capitol at the time. Nine states had ratified. Leaders in New York, North Carolina and Rhode Island were waiting to see if Virginia would endorse the new form of government, or if the product from the Philadelphia convention would be rejected. In that case, the Articles of Confederation would remain the basis for a national government.

Since it was clear the decision process based on the Articles of Confederation had failed, the likely result of a rejection by Virginia was the breakup of the new nation and the formation of separate, regional governments.

Edmund Pendleton chaired the convention. The 61-year old George Wythe and 37-year old James Madison prevailed in the Virginia ratification convention. Wythe served as chair of the Committee of the Whole, which debated the proposal. They agreed the proposed document was not perfect, and Madison had to commit that amendments would be adopted once the First Congress met.

At the start of the Virginia Ratifying Convention debate, delegates were evenly split with 84 in favor and 84 opposed. The final decision on June 25, 1788 was to approve the US Constitution, a decidsion made in a 89-79 vote. A day later the delegates approved amendments they wanted to see added by the first Federal Congress. New York then ratified with a margin of only three votes and Rhode Island by only two.

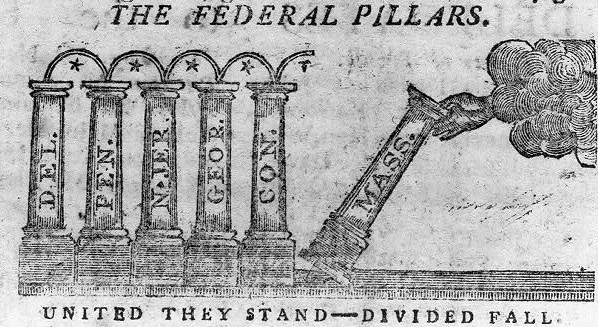

at least 9 states had to ratify the proposed new US Constitution before it could replace the Articles of Confederation

Source: Library of Congress, The federal pillars

Virginia, like New York and Rhode Island, include a provision in its ratification to limit the authority granted to the new Federal government. A 1788 "resumption clause," which the Virginia secession convention cited in 1861, said:8

Madison was true to his promises during the ratification debate to modify the now-implemented Federal Constitution. First he had to overcome Patrick Henry's opposition and get elected to the House of Representatives for the First Congress. There James Madison led the effort to get amendments approved by the Congress and sent to the states for another ratification process.

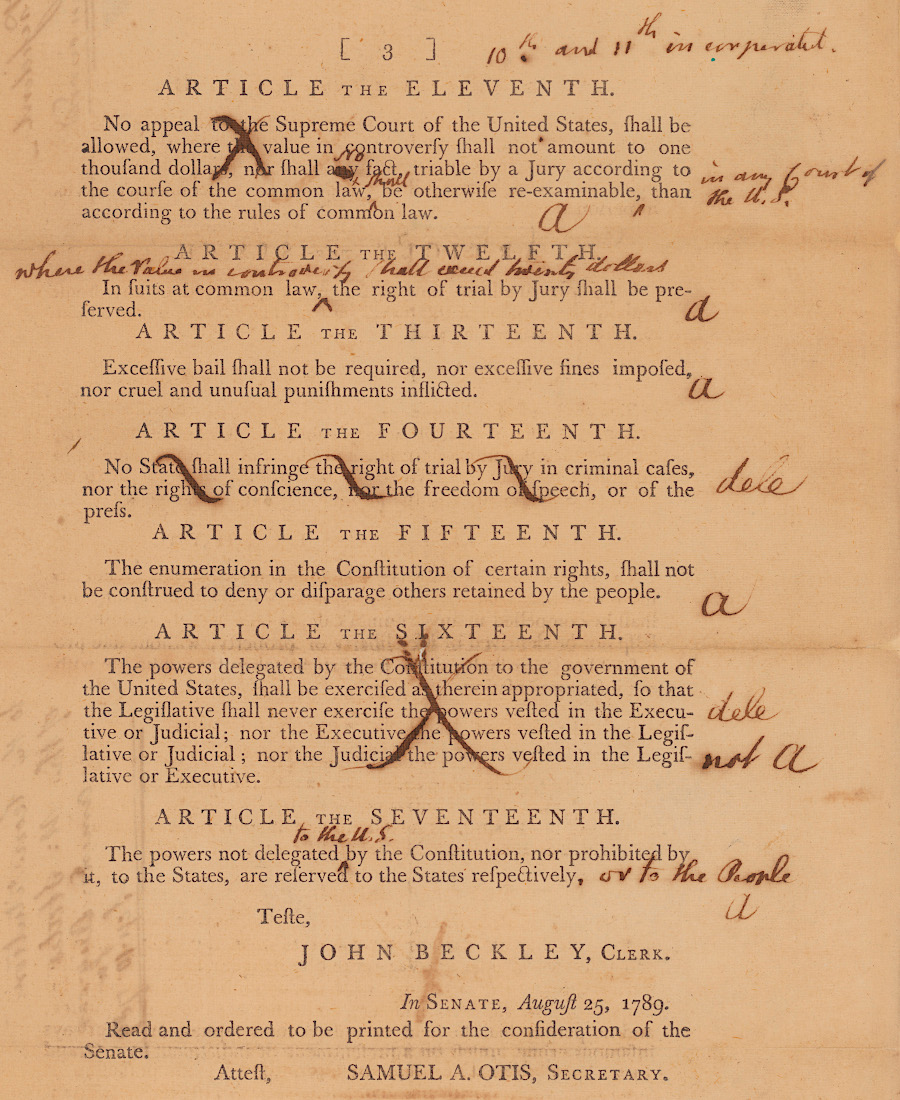

Between June-August 1789, Madison maneuvered 17 amendments through the House of Representatives. Each got the required 2/3 vote for approval. He assumed the wording of the Constitution would be revised, but ultimately all amendments were appended to the original wording.

The decision to add amendments at the end of the original document was one reason his proposed 16th Amendment was rejected by the US Senate. The 16th Amendment would have specified more clearly that the legislative, executive, and judiciary were separate branches of government. The Senate felt it was redundant language. It also addressed the structure of government rather than enumerated rights of the people, and possibly US Senators were reluctant to endorse language that might lead to new restrictions on the powers of the Senate.

The first ten were ratified in 1791 by at least 75% of the states; they are known today as the Bill of Rights. One of the others was finally ratified as the 27th Amendment in 1992.9

in 1872, the Parliament in England authorized the right to meet and speak freely at the Speakers' Corner of Hyde Park in London - but there is no First Amendment in the unwritten English constitution

Madison ended up the House of Representatives because Patrick Henry kept him from being selected as a US Senator. Henry was an opponent of the stronger Federal government, and arranged for Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson to be chosen instead.10

Virginia was the 10th state, not the first state, to ratify the US Constitution. When the United States Mint issued commemorative quarters in 1999-2008, it followed the order in which the states joined the Union. Virginia's quarter was the tenth in the sequence, because the state was the tenth to ratify the Constitution.11

the Virginia state quarter was issued in 2000, tenth in the sequence to match how the states ratified the US Constitution

Source: United States Mint, Virginia State Quarter

The US Constitution has been amended 27 times, starting with the first 10 amendments in 1791. The most recent amendment, ratified in 1992, was one of 12 originally moved by James Madison through the First Congress in 1790. That amendment limited the ability of members in Congress to raise their own pay. It was not ratified by three-fourths of the states until 202 years later.

Virginia has ratified 24 of the 27 amendments. Those not ratified were the ones which authorized the income tax, popular election of US Senators, and granting the District of Columbia three votes in the Electoral College for presidential elections:12

First Amendment: December 15, 1791

Second Amendment: December 15, 1791

Third Amendment: December 15, 1791

Fourth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Fifth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Sixth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Seventh Amendment: December 15, 1791

Eighth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Ninth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Tenth Amendment: December 15, 1791

Eleventh Amendment: November 18, 1794

Twelfth Amendment: between December 20, 1803 and February 3, 1804

Thirteenth Amendment: February 9, 1865

Fourteenth Amendment: October 8, 1869

Fifteenth Amendment: October 8, 1869

Sixteenth Amendment: never ratified

Seventeenth Amendment: never ratified

Eighteenth Amendment: January 11, 1918

Nineteenth Amendment: February 21, 1952 (rejected February 12, 1920)

Twentieth Amendment: March 4, 1932

Twentyfirst Amendment: October 25, 1933

Twentysecond Amendment: January 28, 1948

Twentythird Amendment: never ratified

Twenthyfourth Amendment: February 1, 1963

Twentyfifth Amendment: March 8, 1966

Twentysixth Amendment: July 8, 1971

Twentyseventh Amendment: December 15, 1791 (went into effect May 18, 1992)

Other amendments have been proposed to the states, but have not been ratified by a sufficient number of states to be added to the US Constitution. A notable example is the proposed Equal Rights Amendment.

In 2019, proponents sought to get the General Assembly to make Virginia the 38th state to ratify that amendment. Some lawyers interpreted the exercise as political theater, but others claimed Virginia's vote could make the difference and get the amendment into the Constitution. The State Senate approved the amendment and Governor Northam promised to sign it, but in the House of Delegates the bill was killed in a subcommittee. A parliamentary procedure to force a full vote in the House of Delegates failed in a 50-50 tie, ending the effort to get ratification by Virginia in 2019.

In the November, 2019 elections, Democrats won a majority in both the House of Delegates and the State Senate. The legislature quickly ratified the Equal Rights Amendment in January, 2020. Because the deadline 38 states to ratify had expired in 1982, the action was symbolic and the amendment did not go into effect.13

Only one constitutional convention has generated wording for the US Constitution; all other changes have occurred through the amendment process. There has never been a second convention to replace the version of the US Constitution, as drafted in 1787 and amended since ratification. Political conservatives led by the American Legislative Exchange Council have advocated for a second convention, which could be called either by Congress or by two-thirds (34) of the states.

By 1983, 32 states had passed resolutions calling for a new convention, though 16 had rescinded their call by 2010. The primary focus of convention supporters was to create a constitutional requirement for a balanced budget. However, a convention could propose replacing any part of the existing US Constitution, including equal allocation of two senators for each state or elimination of the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights.

A mock constitutional convention was held in Williamsburg in 2016. It demonstrated how delegates could draft a new document to replace the existing US Constitution, just as delegates in 1787 proposed a complete replacement for the Articles of Confederation.

To date, the Virginia General Assembly has not joined that movement. The legislature has not called for a new national convention to replace the US Constitution. In contrast, in addition to the amendment process, multiple conventions have replaced or revised the Virginia state constitution.14

Both the US Constitution and the Virginia state constitution ultimately derive their authority from the people who are governed, but there is a significant difference in the approach. When Virginia published an updated version of the state constitution in 1950, a footnote to Section 63 included:15

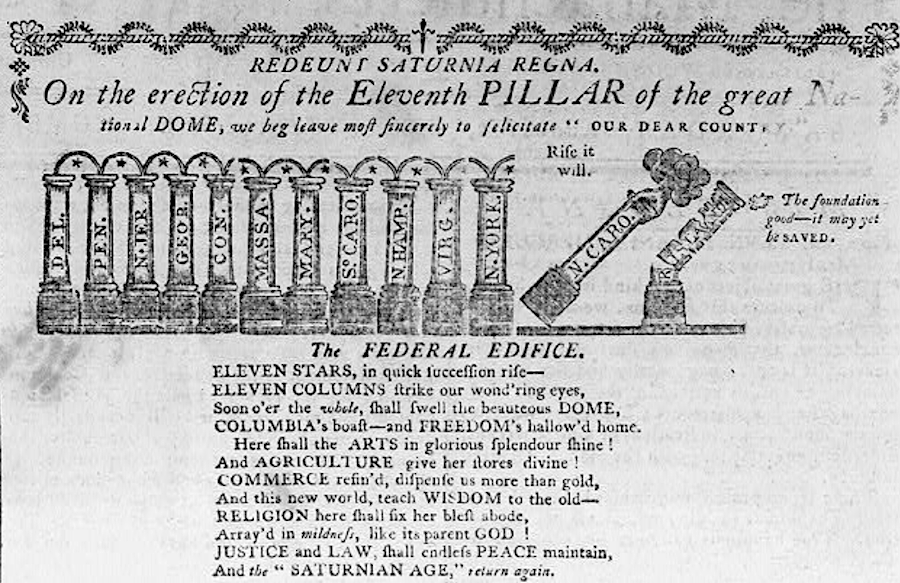

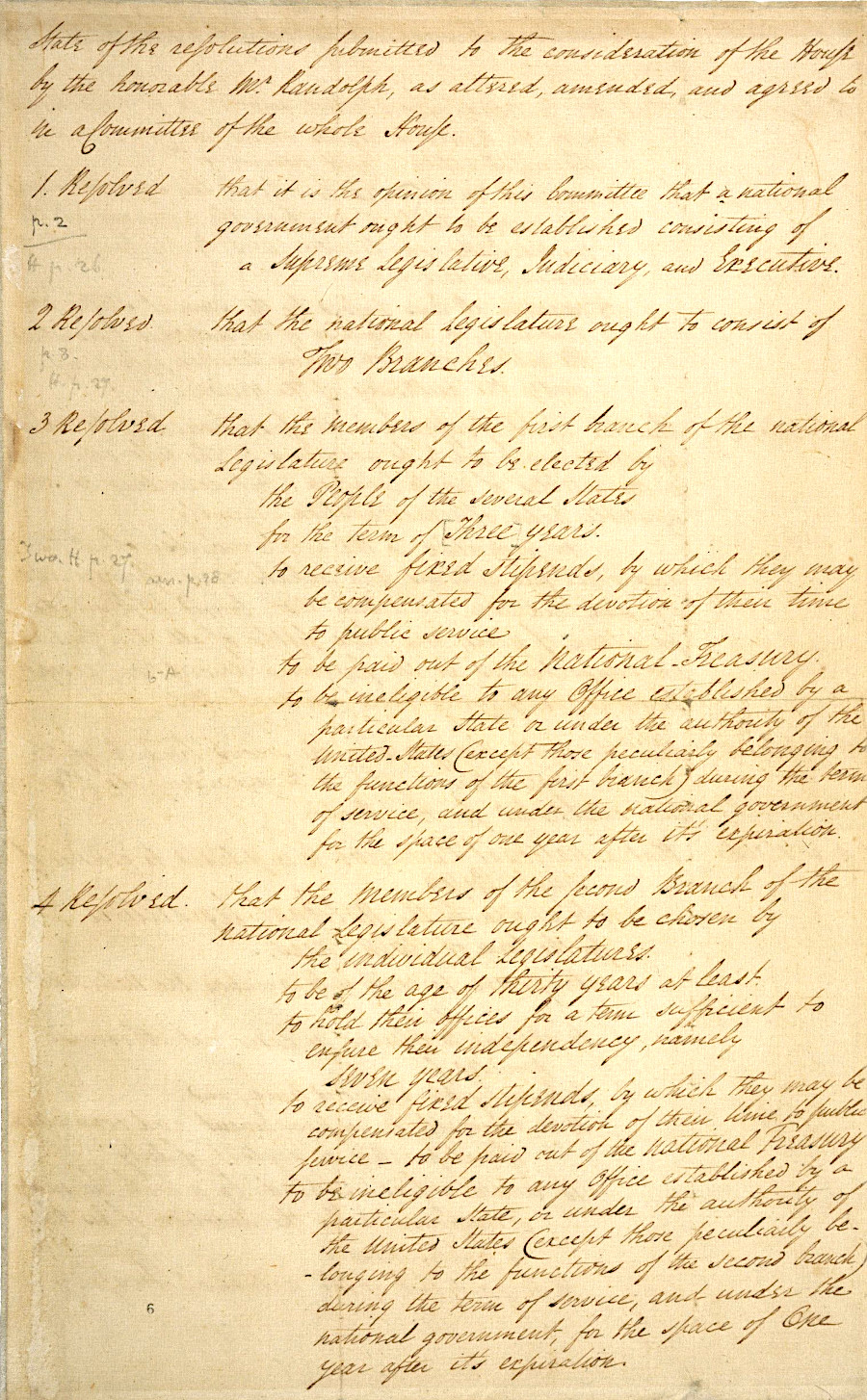

the original Virginia Plan was submitted on May 29, then debated and altered to create this version on June 13, 1787

Source: National Archives, Virginia Plan (6/13/1787)

in 1789 the US Senate consolidated Madison's 17 proposed amendments to 12, in part by deleting the 16th Amendment

Source: National Archives, Bill of Rights