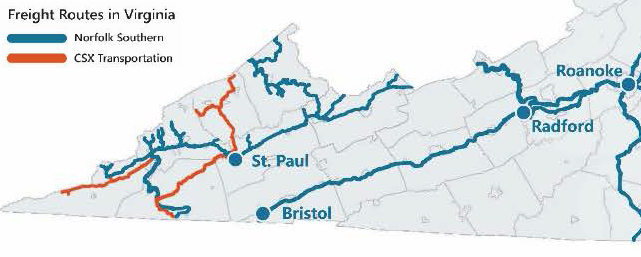

the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads carry coal through Southwest Virginia today

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Virginia Statewide Rail Plan (Figure 2-1)

the Norfolk Southern and CSX railroads carry coal through Southwest Virginia today

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Virginia Statewide Rail Plan (Figure 2-1)

Coal in the Midlothian Basin was near the Fall Line, and relatively easy to transport via the Chesterfield Railroad to a port on the James River. The coal in the western part of the state, especially the rich coal seams in the Appalachian Plateau, was easy to see and easy to mine - but far harder to move to market.

Virginians were aware of the Appalachian coal in 1750. It was suitable for local use, but transportation by mule-drawn wagons over muddy roads to distant markets was not cost-effctive.1.

After the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad reached Cambria (now part of Christiansburg) and Central Depot (now Radford) in the 1850's, coal from the New River Valley near Blacksburg was shipped east to Norfolk. The Merrimac Mine in Price Mountain (Montgomery County) supposedly supplied the coal that fueled the Confederate ironclad ship CSS Virginia which battled the Union ironclad Monitor in Hampton Roads in 1862. The Confederate ironclad had been constructed from the USS Merrimac. Its superstructure had burned when the US Navy abandoned the shipyard at Gosport in 1861, but the hull had sunk in the water and been recovered by the Confederate Navy.

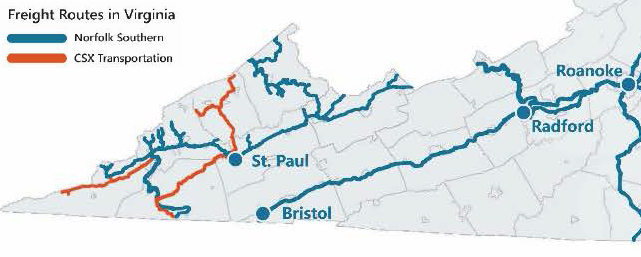

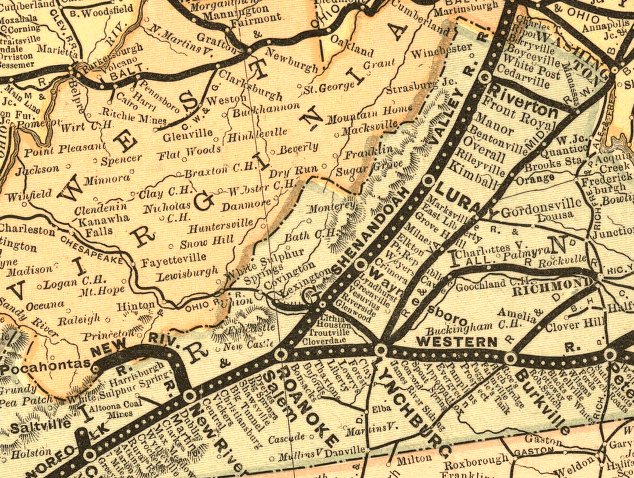

the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was built in the 1850's to haul agricultural products, timber, and iron, 30 years before coal was transported from the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant (1852)

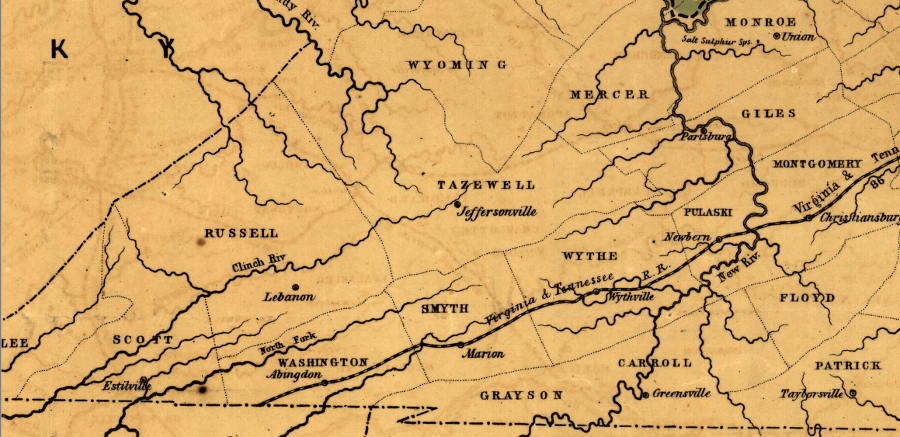

The Norfolk and Western Railroad was the first line to climb out of the Valley and Ridge province, cross the Blue Ridge and the Valley and Ridge physiographic provinces, and reach Virginia's Appalachian Plateau. The Norfolk and Western Railroad started shipping coal between Pocahontas and Norfolk in 1883, over a century after the Midlothian Basin mines were first opened.

To get from the Appalachian Plateau to the Atlantic Ocean, coal trains crossed the eastern edge of the Appalachian Plateau (the Allegheny Front), dropped down into the Valley and Ridge province, climbed back up and across the Blue Ridge province, then crossed the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain provinces. Trains reached navigable, sea level water at the Fall Line ports on the boundary of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, before tracks were extended to Portsmouth, Norfolk, and ultimately Newport News in Hampton Roads.

Due to topography, there were many ups and downs for heavy trains headed east, loaded with Appalachian Plateau coal. Return trips west, with empty cars headed back to the coal mines, were less troublesome because the locomotives were pulling lighter loads. Railroad engineers tried to design tracks with a "controlling grade" that was more gentle headed east, so locomotives could pull the heavily-loaded cars up slopes at a lesser angle.

Norfolk and Western route to Pocahontas

Source: Library of Congress - Map showing the Norfolk & Western Railroad and its connections (1887)

In the 1880's, the new Norfolk and Western Railroad built a new line westward, downstream along the New River, to connect the old Virginia and Tennessee mainline between Lynchburg and Bristol to the Appalachian coalfields along the Virginia-West Virginia border.

The new track snaked westward from Radford down the New River Valley. The river flows to the west through Montgomery and Giles counties, so the valley gets lower towards the west. The railroad had to climb up to reach the coal on the plateau.

To climb up, the tracks left the New River valley at Glen Lyn and ran up the valley of the East River. The new railroad crossed the state border into West Virginia by following the East River valley to the watershed divide at Bluefield. The track then looped in a long curve down the Bluestone River valley to reach the coal at Pocahontas.

That route was not the most direct, but the longer distance allowed engineers to avoid steeper grades that would have been required to climb over the ridges.

round wheels on rails require flat routes, with grades typically less than 2%

Source: Pixabay

Question: Why spend money building a longer rail line, rather than building in a straight line between Radford and Pocahontas?

Answer: locomotives lose most of their power when trying to go uphill. The surveyors who located the route looked for easy grades. They needed to minimize the "up and down" so trains could travel on level (or close-to-flat) grades. Locomotives, while powerful in pulling trains forward, quickly lose capacity when forced to travel uphill.

A complex formula is used to determine the pulling ability ("tractive force") of the engines in a locomotive, but that power is used to spin smooth metal wheels on slick rails. Once a train gains momentum, the smooth metal track minimizes friction.

Just one modern diesel locomotive can haul 100 cars carrying 150 tons of coal on flat ground. However, any uphill/downhill incline (the "grade" of a railroad track) dramatically reduces the ability of a locomotive to move the load. On a 2% grade, 43 pounds of the locomotive tractive force would be required to haul the load uphill.2

a narrow-gauge railroad built with a 30% grade at Fort Belvoir in 1918 used a cable hoist rather than a locomotive to move cars

Source: National Archives, Military Administration - Transportation - Rail - Construction - Railroad Construction By Engineers, Belvoir, Virginia

The physics of gravity and traction forced railroads to build longer lines through valleys, or to construct expensive tunnels, in order to avoid grades over 2% (a 2-foot rise in elevation over a horizontal distance of 100 feet, or a change in elevation of about 100 feet/mile). If it was not cost-effective to avoid a steep grade via extra trackage or a tunnel, then railroads had to purchase more-powerful locomotives, split trains and haul then in portions over the hills, or add additional locomotives to the trains to help haul the weight through steeper sections of track.

Louisa Railroad grade from South River west to Staunton, showing feet/mile in sections

from Waynesboro-Fishersville, Fishersville-Christian's Creek, and Christian's Creek-Staunton

Louisa Railroad route from South River west to Staunton

Source: Library of Congress - A map of the Virginia Central Railroad, west of the Blue Ridge, and the preliminary surveys, with a profile of the grades

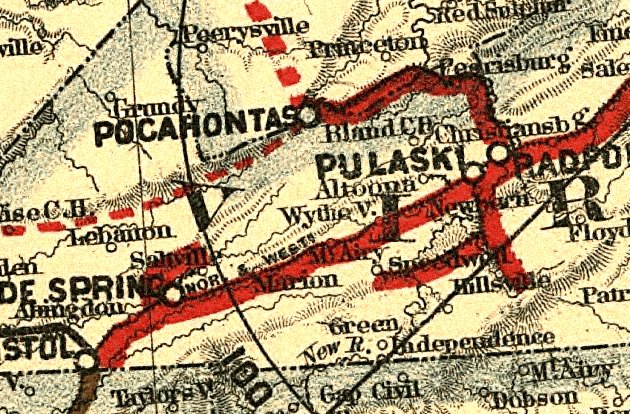

In the 1900's, four railroads hauled most of the Virginia coal from the Appalachian Plateau to salt-water ports at sea level: the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O), Norfolk and Western (N&W), Virginian, and Clinchfield railroads. Those historic railroads demonstrate the impact of topography on transportation. Prior to the Civil War, boosters of extending the Richmond and Danville Railroad to Greensboro, North Carolina claimed it would become a coal-hauling line due to the coal in the Dan River Basin, and coal would encourage manufacturing growth in North Carolina. However, the amount, quality, and accessibility of that coal was too thin to justify investment in a major mining operation in that basin.

Today, tracing their routes require knowing some business history. The C&O and the Clinchfield have been incorporated into the CSX railroad, while the Norfolk and Western and the Virginian are both part of the Norfolk Southern railroad now.

Prior to the Civil War, boosters of extending the Richmond and Danville Railroad to Greensboro, North Carolina claimed it would become a coal-hauling line due to the coal in the Dan River Basin. North Carolina legislators were encouraged to allow construction of track connecting Greensboro to Danville. That line might divert agricultural products from the North Carolina Piedmont to Richmond, away from the North Carolina towns and port at Wilmington, but coal from the Dan River Basin would encourage manufacturing growth in North Carolina. In the end, the amount, quality, and accessibility of that coal was too thin to justify investment in a major mining operation. The Piedmont Railroad was built as a military necessity in 1862-63 to deliver supplies to the Confederate army fighting in Virginia, not to haul coal.3

the Blue Ridge Tunnel built by Claudius Crozet carried the Virginia Central under the Blue Ridge, until a new tunnel opened in 1944

Source: Library of Congress, General View of Entrance to Blue Ridge Tunnel (Left) From Southeast. Original Blue Ridge R.R. (Crozet) Tunnel Is Visible at Right. - Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, Blue Ridge Tunnel, Highway 250 at Rockfish Gap, Afton, Nelson County, VA

Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O)

After the Civil War, the Virginia Central became part of the C&O. The C&O was constructed west from Clifton Forge (originally known as Jackson's River Station) after the Civil War. Collis P. Huntington financed the expansion to connect the Ohio River and the Atlantic seacoast, ultimately choosing to build his port at Newport News to ship coal up to New England or across the Atlantic Ocean.

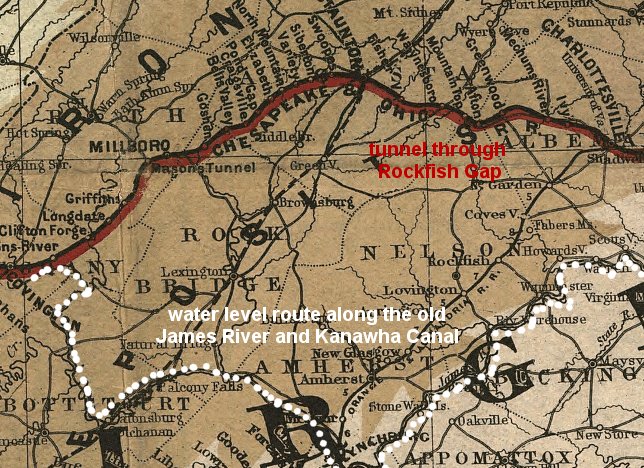

The C&O built westward across the Allegheny Front, but it also revised the existing route east of Clifton Forge. The Virginia Central used the first railroad tunnels in Virginia (built at state expense) to cross the Blue Ridge at Rockfish Gap, reaching Jackson's River Station/Clifton Forge at the western edge of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province prior to the Civil War. In the 1880's, after Northern capitalists provided new funding to expand the railroad,, the C&O found a way to bypass the steep climb over the Blue Ridge. The railroad acquired the James River and Kanawha Canal path along the James River, and established a new line with a much more gentle grade to Richmond. (Technically, the canal path had been purchased earlier by the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad, which the C&O acquired.)

Getting further west into the Appalachian Plateau was also a technological challenge. Even today, with a tunnel to reduce the peak grade on the climb up Allegheny Mountain, the modern CSX track still has a 1.1% grade between Alleghany Tunnel (2,052 foot elevation) and Clifton Forge (1,031 foot elevation). However, locomotives are hauling heavy trains downhill, and empty coal cars uphill. The loaded trains from the West Virginia coalfields are going downhill after climbing out of the New River Gorge and entering the James River valley, and only empties returning from Newport News are forced to climb that grade.

Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad routes across the Blue Ridge (click on image for larger map)

Source: Library of Congress - Map of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad and its connections (1873)

You will also see empty CSX coal cars hauled along the old Blue Ridge Tunnel route, which has now been leased to the Buckingham Branch Railroad. If you're waiting for an Amtrak train at the Charlottesville or Staunton train stations, note the locomotive (those owned by CSX are painted blue and yellow), the type of cars being pulled (the Buckingham Branch Railroad still hauls some standard boxcars, cars specialized for lumber, and of course intermodal trailers on flatcars), and the direction of travel (if you see coal cars, you'll see just empties headed west unless there's been a disruption in normal traffic patterns).

For eastbound freight, the ruling grade - which determines the maximum locomotive power required to move traffic on the railroad line - is 0.6% on the western side of Allegheny Tunnel. Once past Clifton Forge, the coal-carrying CSX trains on the old C&O have a relatively gentle glide traveling nearly 1,000 feet downhill along the James River through the Blue Ridge at Balcony Falls to Richmond (54 feet elevation). East of the Fall Line at Richmond, the CSX drops just another 30 feet before reaching the docks at Newport News (at 15 feet elevation).4

CSX water route vs. Blue Ridge Tunnel route

(Clifton Forge is 1.083 feet in elevation above sea level)

Source: National Atlas

the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) relied upon the Blue Ridge Tunnel to haul coal across the Blue Ridge

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Blue Ridge Tunnel

bricks lined the western portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel, where it passed though the Chilhowee Group of sedimentary formations

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Blue Ridge Tunnel

Norfolk and Western (N&W)

The eastbound Norfolk and Western crossed Flat Top Mountain at Bluefield, where the ruling grade now is 1.4% for traffic headed east. Returning empties face an even-steeper 1.6% grade from Glen Lyn up to Bluefield. The loaded trains have to travel up the New River Valley from Glen Lyn (1,520 feet elevation) to cross the Allegheny Front at Christiansburg (2,052 feet elevation) to reach the Roanoke River valley. The last part of that eastbound climb at Christiansburg involves a 1% grade up to the crest - but returning westward, the Norfolk and Western was engineered for locomotives to pull empties over a 1.3% grade to the crest of Allegheny Mountain at Christiansburg.

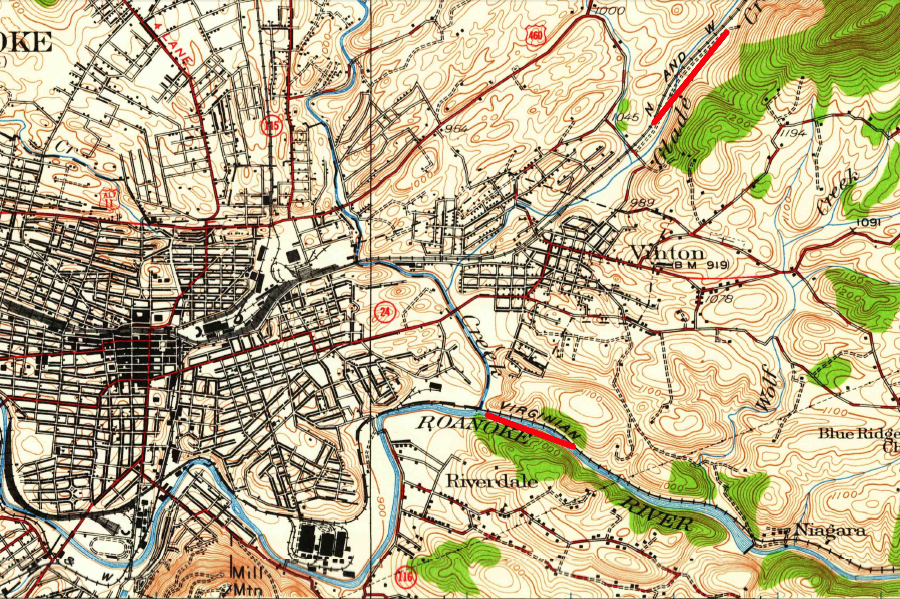

Unlike the C&O, the N&W developed no water-level route through the Blue Ridge to an Atlantic Coast port. Instead, trains from the Appalachian Plateau (including the town of Pocahontas) climbed out of the New River Valley at Christiansburg, followed the Roanoke River down to Roanoke (905 feet elevation), then climbed a 1.2% grade to cross the Blue Ridge (1,296 elevation).5

Norfolk and Western in 1882, when the line up the New River was a branch off the main line between Lynchburg and Bristol

Source: Library of Congress - The Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia Air Line; the Shenandoah Valley R.R.; Norfolk & Western R.R.; East Tennessee, Virginia, & Georgia R.R. (its leased lines,) and their connections (1882)

The original Virginia and Tennessee (V&T) track between Lynchburg and Bristol was a general merchandise line. It was acquired by the Norfolk and Western Railroad, and a great business in hauling coal was developed by that railroad - but the track was not designed initially to haul heavy loads of coal from the mountains to sea level. The line provided an up-and-down train ride. "In the 200 miles between Lynchburg and Bristol, V&T's total rise and fall was in excess of 5700 feet, more than five times greater than the difference in elevation between the two endpoints!"6

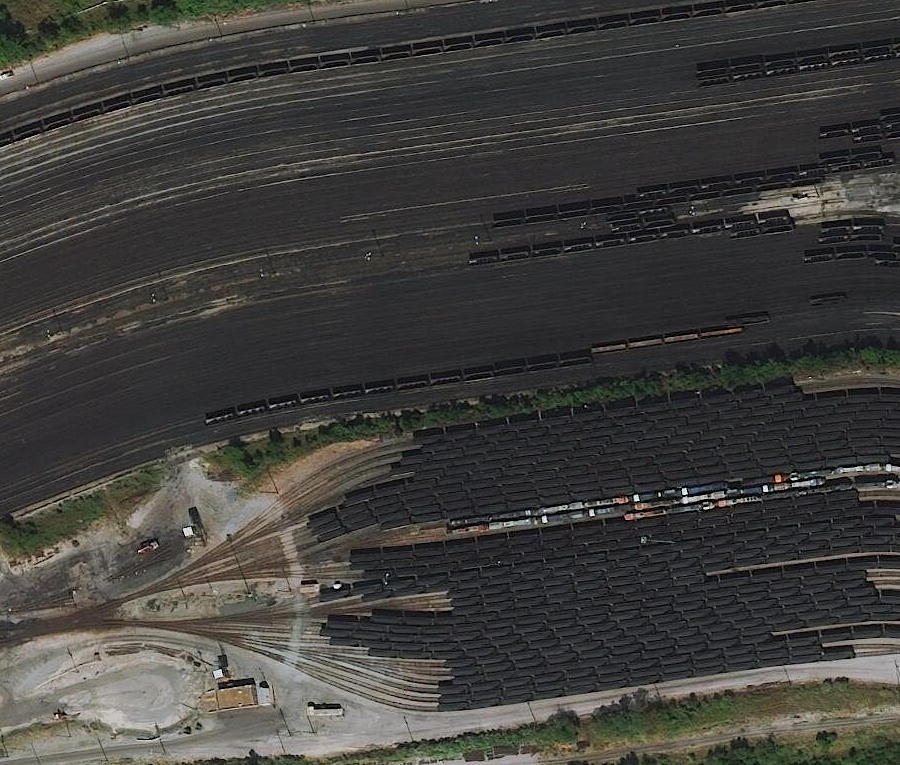

"Pusher" locomotives are used to provide supplemental power where the grade is especially steep. Using pushers enables the railroads to minimize the investment in capital equipment. Coal trains are slow freight, intended to travel at a steady and cost-effective pace. For example, for most of the distance between Glen Lyn on the West Virginia border and Norfolk, one or two steam locomotives could haul a loaded coal drag. Only at a few spots was additional tractive effort required. One of those today is Whitethorne, west of the Allegheny Tunnel at Christiansburg. Two locomotives are often stationed there to attach to the back of a coal train and help push it over the crest and through the tunnel. Once into the Roanoke River valley, the locomotives cut free and return to Whitethorne to help the next coal drag.

the Norfolk and Western Railroad brought coal across the Blue Ridge to Lamberts Point in Norfolk

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginian

The Virginian was engineered and built 50 years later than the Norfolk & Western, and designed with one purpose - to carry coal from West Virginia to Hampton Roads. The ruling grades on the Virginian were substantially less than on the N&W, because the Virginia built a tunnel to cross the New River-Roanoke River divide. The Virginian Railroad's Allegheny Tunnel elevation was 1953 feet, about 50 feet lower than the N&W route eastward to Roanoke. The eastbound grade of the Virginian from Whitethorne to Merrimac, across Allegheny Mountain at Christiansburg was 0.75%, in contrast to the N&W's 1% grade.

Further east, the Virginian followed the Roanoke River through the Blue Ridge, traveling downhill while the N&W climbed a 1.2% grade through the Blue Ridge gap. The N&W connected Roanoke to Lynchburg, while the Virginian bypassed the towns on the Piedmont. That route sacrificed the chance to pick up some general merchandise traffic, but maximized the efficiency of the route to Norfolk. The Virginian finally started to climb out of the Roanoke River valley at Red Hill (the last home of Patrick Henry), reaching the drainage divide with a 0.2% grade at Abilene. The Virginian and the N&W ran in parallel at Abilene, headed down the Appomattox River valley.

The modern Norfolk Southern route between West Virginia and Norfolk combines the best grades of the N&W and Virginian routes. Trains loaded with coal climb out of the New River valley and go through the Allegheny Tunnel, the route with the more-gentle grade, then follow the old Virginian route east along the Roanoke River. This bypasses both the Blue Ridge grade and the old 0.5% grade at Bray Hill, east of Lynchburg (where the N&W climbed out of the James River valley). Norfolk Southern trains with empty hopper cars returning from Norfolk follow the old N&W route, with a 1.3% grade in a 12-mile climb from Elliston in the Roanoke River to Christiansburg at the crest of Allegheny Mountain.7

Light trains carrying empty hopper cars take that route into the New River valley, because it leaves the Allegheny Tunnel on the old Virginia route free for the heavily-loaded coal trains headed east.

the Norfolk and Western Railroad and the Virginian Railroad took separate routes east from Roanoke

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Roanoke VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1929)

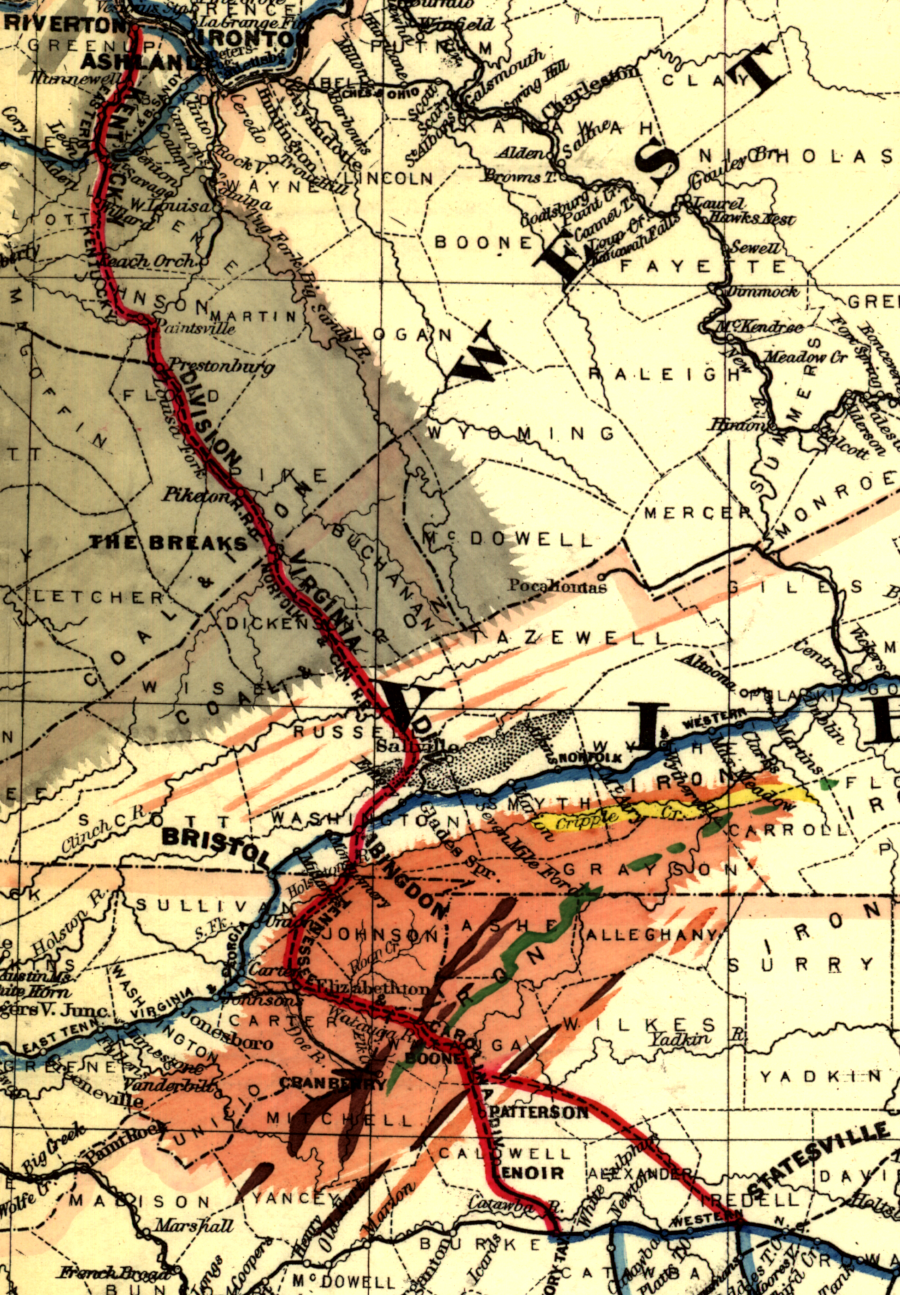

Clinchfield

The Clinchfield was built to haul coal from Dickenson County to Spartansburg, South Carolina. The route was southward along the Clinch River, and the climb over the Blue Ridge occurred in North Carolina. However, a later extension was built northward to connect St. Paul with Elkhorn City in Kentucky, allowing the Clinchfield to ship coal into the Ohio River valley. The Sandy Ridge tunnel was built north of Dante to minimize the grade required for the Clinchfield to cross the Tennessee Valley divide, between the Clinch River and the Russell Fork of the Big Sandy River.

the Clinchfield Railroad built its line connecting Kentucky and Virginia coal fields through The Breaks

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Consolidated Southern Railway, Kentucky Division--Eastern Kentucky R.R. Virginia Division--Norfolk & Cincinnati R.R. Tennessee & Carolina Division and its connections (1883)

multiple railroads crossed the Kentucky and Virginia border between Cumberland Gap and the Tug Fork

Source: Library of Congress, Preliminary map of Kentucky 1891

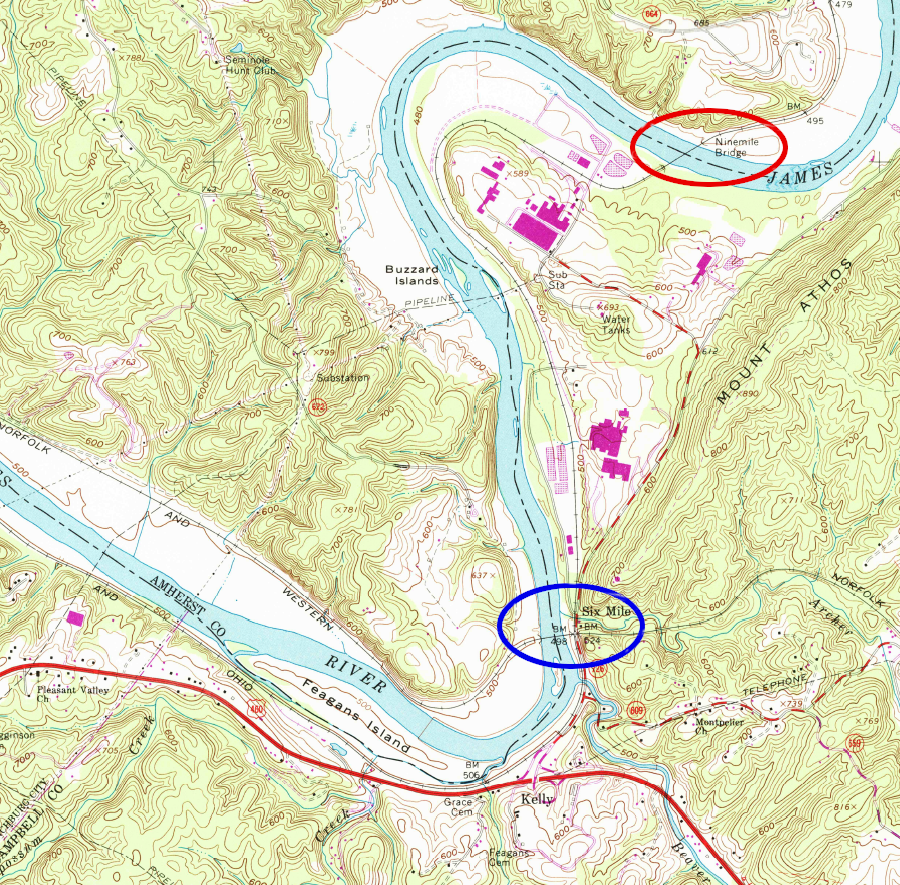

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway hauled coal across the James River via a bridge nine miles downstream of Lynchburg, while the Norfolk and Western Railway used Six Mile Bridge

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Kelly, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1963)