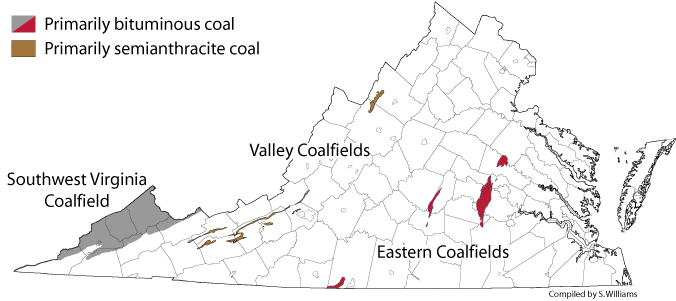

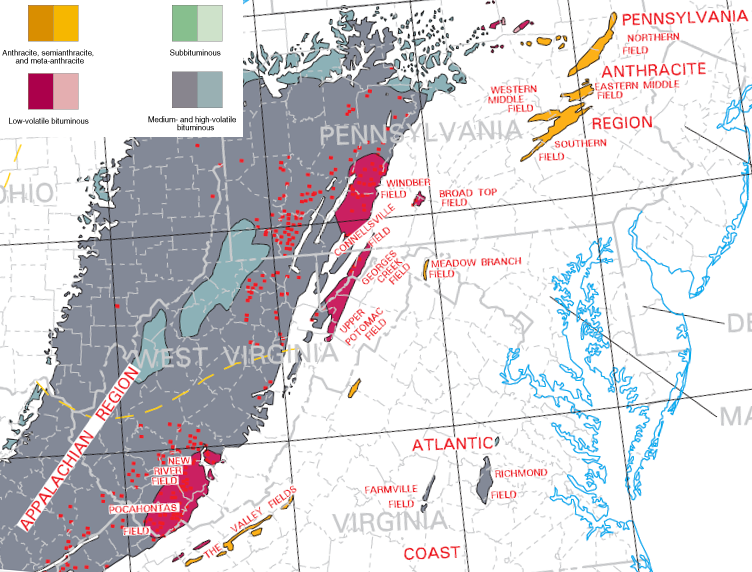

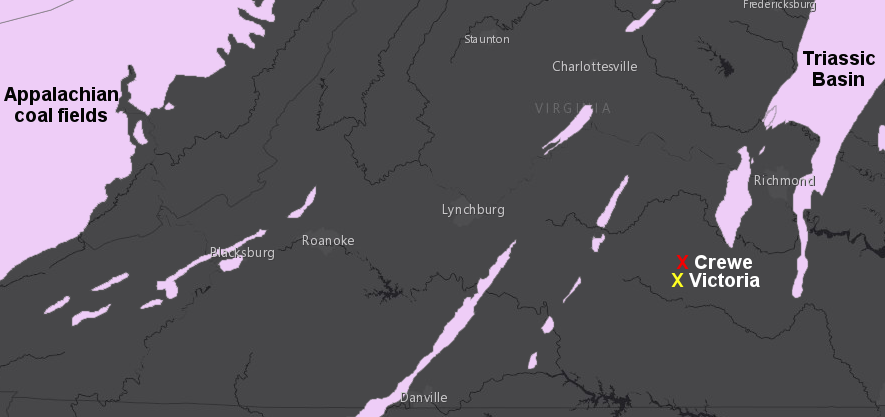

Virginia's Valley and Ridge coal is semi-anthracite, while Appalachian Plateau and Triassic Basin coal is bituminous

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Coal

Virginia's Valley and Ridge coal is semi-anthracite, while Appalachian Plateau and Triassic Basin coal is bituminous

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Coal

Most of the coal in western Virginia was created 359-299 million years ago, when what today is Virginia was near the Equator. Rivers flowed off mountains east of today's Appalachian Plateau, draining into a shallow sea to the west. Swamps developed at the mouths of the rivers flowing into the Central Appalachian Basin. Similar swamps in Triassic Basins led to coal deposits forming 250-201 million years ago. Coal deposits in Wyoming, Colorado and other western states are significantly younger.1

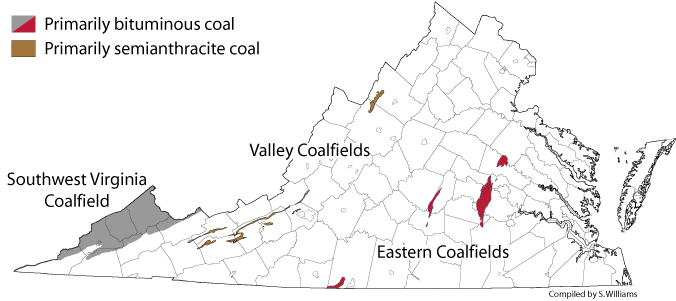

the location of Virginia's anthracite, semi-anthracite, and bituminous coal reflects the different pressures exerted by the collision of continental plates as Pangea was created - and the absence of pressure when the Richmond coal fields formed

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Coal Fields (Plate 6a, digitized by University of Richmond)

The plants in the swamps absorbed carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and photosynthesis provided the energy to "fix" the carbon in plant cells. When plants died, bacteria/fungi decomposed some organic material. Other plant cells were covered by sediments and the remains of yet more plants. Because oxygen was blocked from reaching the buried layers, plant photosynthesis in the warm climate created organic material faster than it could decay during the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian ("Carboniferous") periods.

What today is the Appalachian Plateau experienced cyclical periods of subsidence. Swamps near the shoreline sank along with the underlying block of crust, and sediments (first mud, then sand) covered the organic deposits. When basins subsided low enough to be covered by the nearby ocean, lime-rich sediments were deposited on top of the mud and sand. When tectonic uplift would raise the land above sea level, fresh-water swamps would grow again.

Sediments that washed off the mountains and accumulated during high sea levels created pressure and heat at depth. That transformed the dead plant cells into peat and then into coal, as volatile gases were driven off and carbon in the organic material was concentrated.

The cycle of swamp development during low sea levels and sedimentary deposition during higher sea levels was repeated often. As sediments were accumulated in the basin, heat/pressure metamorphosed the mud layers into shale, the sand layers metamorphosed into sandstone, the lime-rich sediments metamorphosed into limestone, and the organic swamp layers metamorphosed into coal.

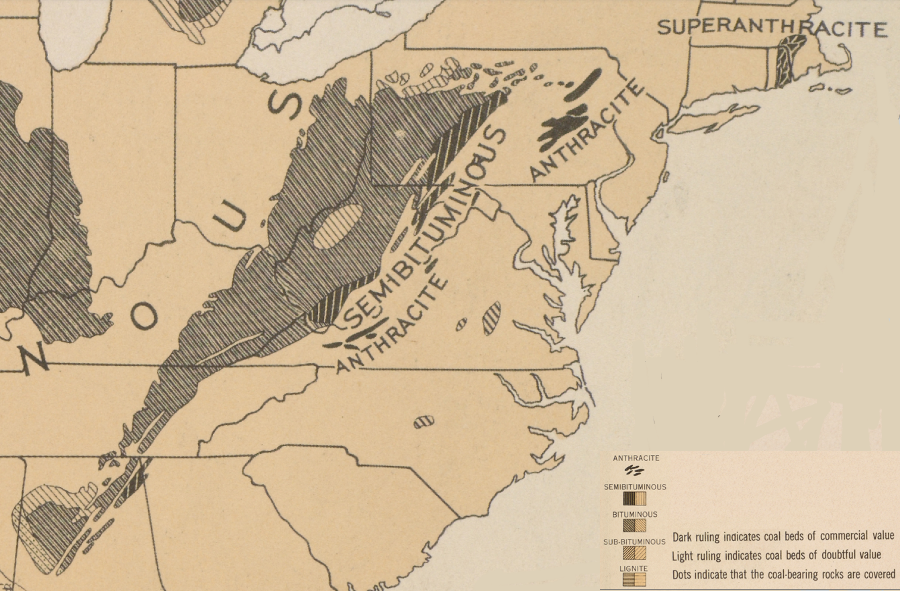

The percentage of carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and other elements in the coal varied depending upon the plants that were in the swamp originally, and the conditions under which the organic material was compressed into coal. Coal with a low percentage of sulfur and ash is sold as metallurgical coal, and is more valuable than thermal coal burned in power plants. Metallurgical ("met") coal is heated in an oven without oxygen, creating a carbon-rich product known as coke that was used in manufacturing steel.

in 1974, metallurgical coal was processed into coke near the mines in Tazewell County before shipment to steel mills

Source: National Archives, Coke Furnaces At Keen Mountain, Near Richlands, Virginia and second image

What is now the Appalachian Plateau physiographic province of Virginia ended up with 76 discrete coal beds, of which about half are mined commercially today. The four most valuable coal beds were named Pocahontas No. 3, Jawbone, Splash Dam, and Dorchester. Stratigraphic intervals that include layers of coal deposited in the Pennsylvanian time period (323-290 million years ago) vary in thickness from 800 feet to over 5,000 feet. The thickest stratigraphic intervals are in the eastern side of the Southwest Virginia Coalfield, where more sediments washed down mountains on the east side of the basin.2

Source: USGS Open-File Report OF 96-92, Coal Fields of the Conterminous United States

The old plant material was squeezed by overlying sediments in the Appalachian Plateau of southwestern Virginia (modern-day Buchanan, Wise, and Dickenson counties) to drive off water and other volatile gases to form bituminous coal. The organic materials were not buried deep enough to concentrate the percentage of carbon to form anthracite or even semi-anthracite coal beds.

The tectonic pressure from the Alleghenian orogeny was diffused by the cracking, thrusting, and folding of the sedimentary layers east of the Appalachian Plateau, creating the wrinkled landscape of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. The energy of the orogeny that formed the supercontinent of Pangea was weak to the west of what is now labelled the Allegheny Front, and the bituminous coal beds on the Appalachian Plateau were not metamorphosed further.

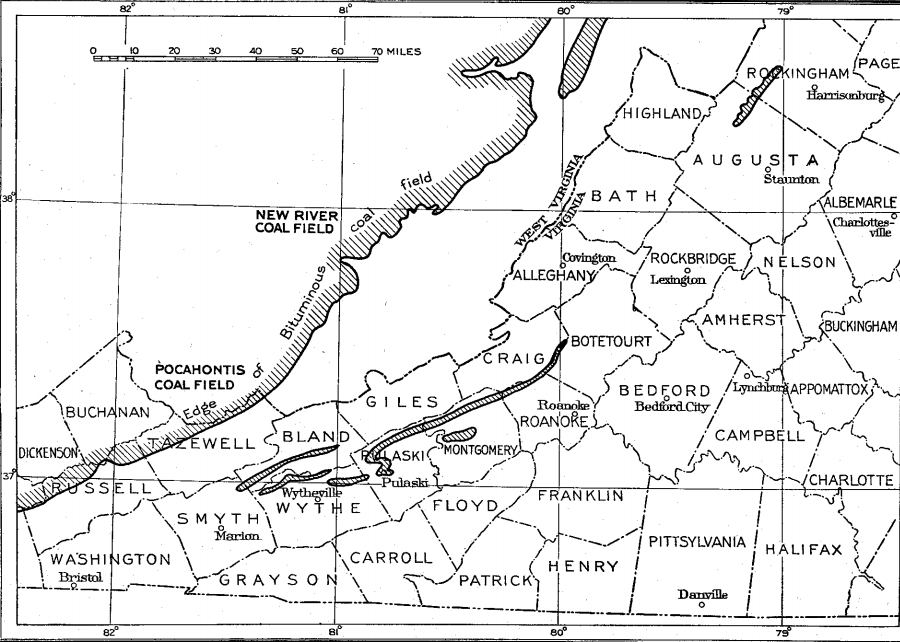

The coal beds in Montgomery, Augusta, and Rockingham counties were in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province of Virginia. Those coal beds were closer to the collision of Gondwana (Africa) with Laurentia (North America). Those beds were buried deep enough and squeezed enough in the Alleghenian orogeny to be metamorphosed into semi-anthracite.

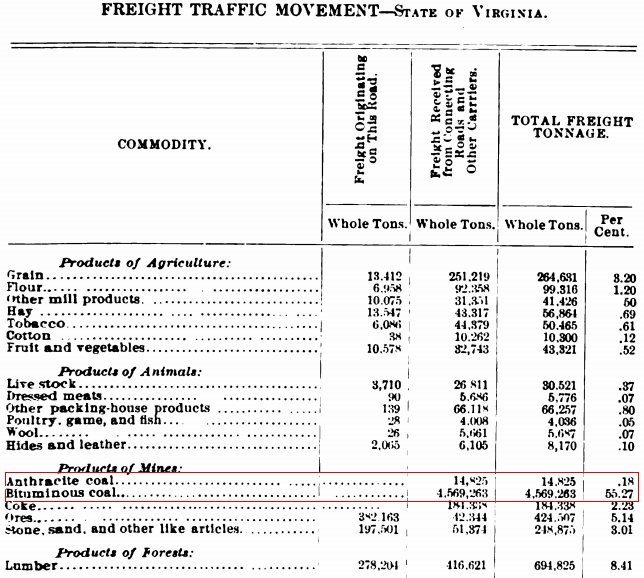

in 1905, the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad transported a little anthracite and a lot of bituminous coal

Source: Annual Report of the State Corporation Commission of Virginia - Volume 2 (1905), Chesapeake Western Railway (p.113)

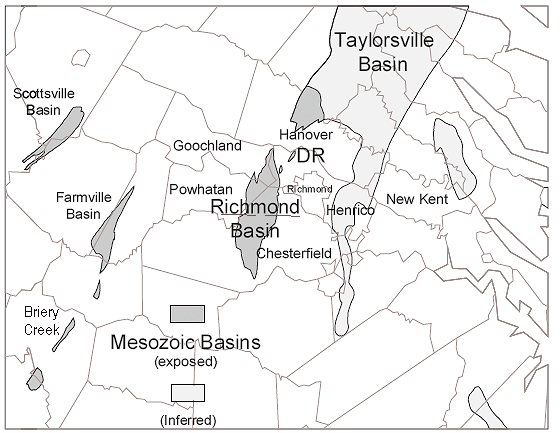

The coal beds at Midlothian and Farmville are younger that the coal beds on the Appalachian Plateau near West Virginia and Kentucky. The coal beds in the Triassic Basin near Richmond formed in similar swamps, but only 205 to 245 million years ago. That Richmond basin was formed as Pangea was splitting up and the Atlantic Ocean developed, after the Alleghenian orogeny.

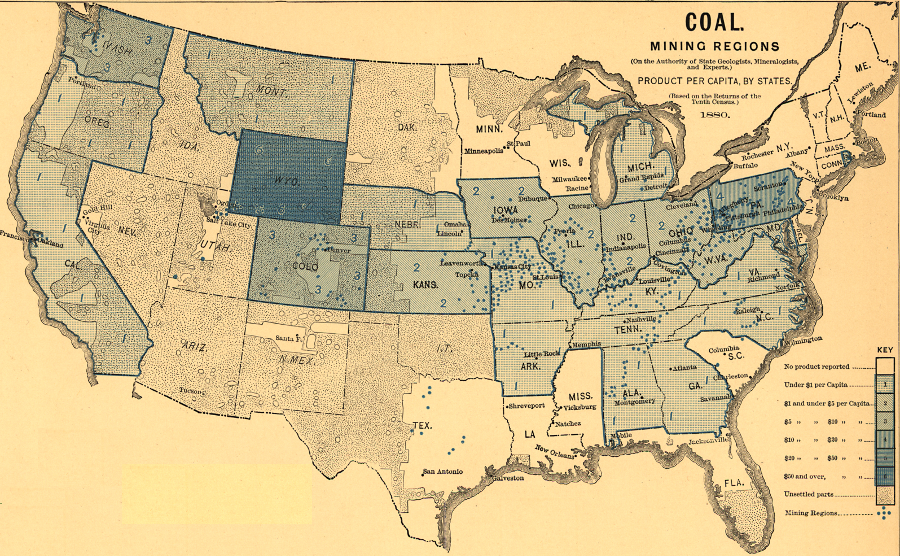

Most coal in western states is also younger than the Alleghenian orogeny. Montana has 30% of the coal resources in the United States, more than any other state. That coal developed less than 200 million years ago, at a time when dinosaurs were wandering through the swamps.

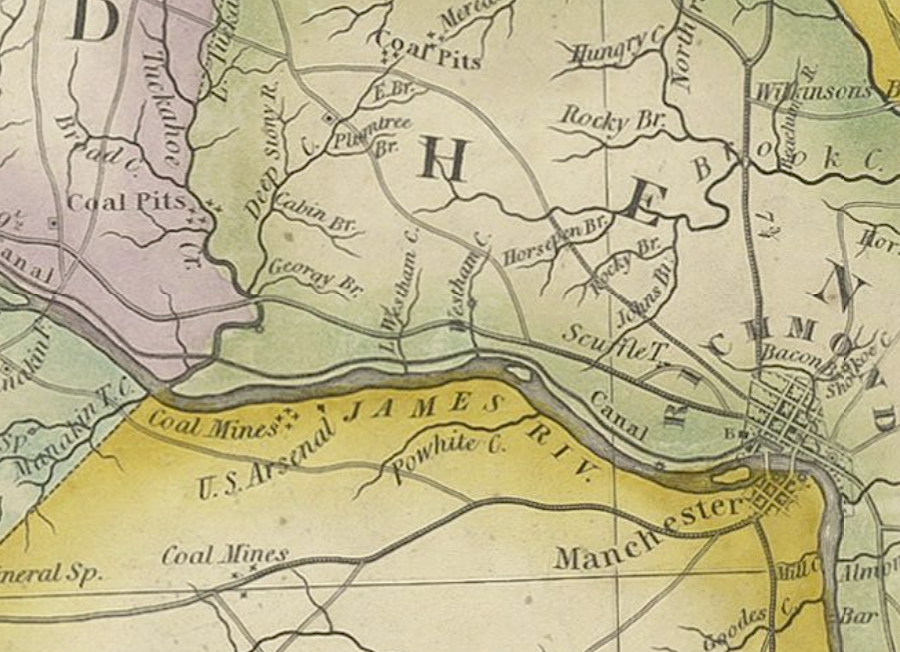

Virginia's first coal mines were in Chesterfield and Henrico counties

Source: Library of Virginia, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law, from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents (John Wood and Herman Böye, 1826)

Though the coal beds in Chesterfield County are east of the semi-anthracite coal beds in Montgomery and Rockingham counties, they were not in existence during the Alleghenian orogeny. In the Triassic Basin, pressure to convert organic plant material into coal came from just the weight of overlying sediments, without tectonic squeezing. The late development of the Triassic Basin coal, when Pangea was splitting apart and the tectonic pressures involved expansion rather than compression, explains why the coal beds east of the Blue Ridge are bituminous rather than semi-anthracite.

As a result, Virginia has bituminous coal east and west of the semi-anthracite coal in Montgomery and Rockingham counties. During the Alleghenian orogeny, tectonic forces on what is now the Appalachian Plateau were not sufficient to compress the organic sediments into anthracite. The organic sediments in the Triassic basin at Midlothian never experienced an orogeny, and have been compressed into bituminous coal just by the pressure of overlying sediments. Only the coal beds in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province were in existence and close enough to the pressure of colliding tectonic plates to become semi-anthracite.

anthracite and semi-anthracite coal fields (shown in yellow) are located in the Valley and Ridge province of Pennsylvania and Virginia, where burial underneath ancient mountains formed in Africa-North America collision created extra heat/pressure

Source: USGS Open-File Report OF 96-92, Coal Fields of the Conterminous United States

The early colonists were aware of the coal near Richmond, but chose to use wood as their primary fuel. As historian Robert Beverley noted in 1705:3

The first Virginia coal mining started in the 1700's near Midlothian in Chesterfield County. From Chesterfield County south of Richmond, coal was carried on rails in mule-pulled carts to Manchester and Richmond. The mules were later replaced by the first locomotives in Virginia, which were fueled by wood.

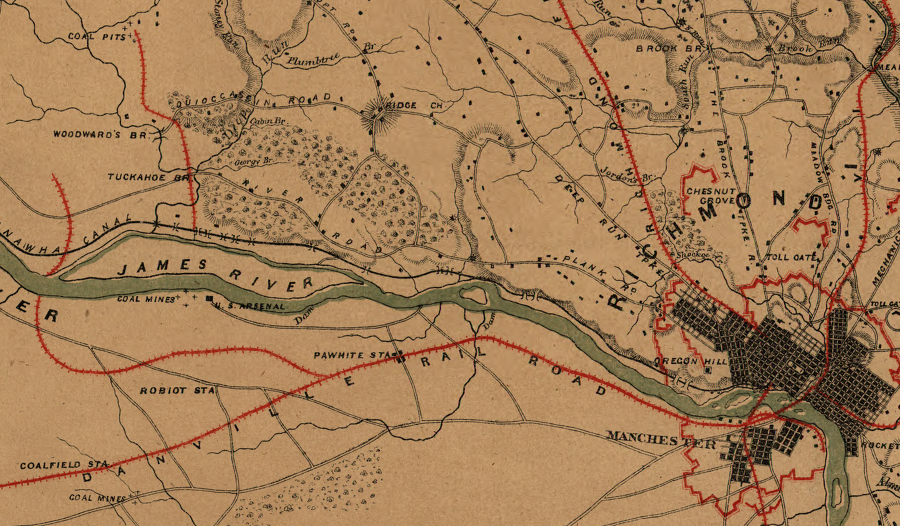

coal was mined from pits in the Triassic Basin and carried to Richmond by railroads and boats before the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Military topographical map of eastern Virginia

The small Midlothian coal field was valuable to the local market, and was exported to Caribbean islands. The coal was valued for its ability to provide heat, and reportedly was used in the White House fireplaces when Thomas Jefferson was president. In addition to the coal mined at Midlothian, the James River and Appomattox River waterpower was a major factor in the development of manufacturing at Richmond and Petersburg.

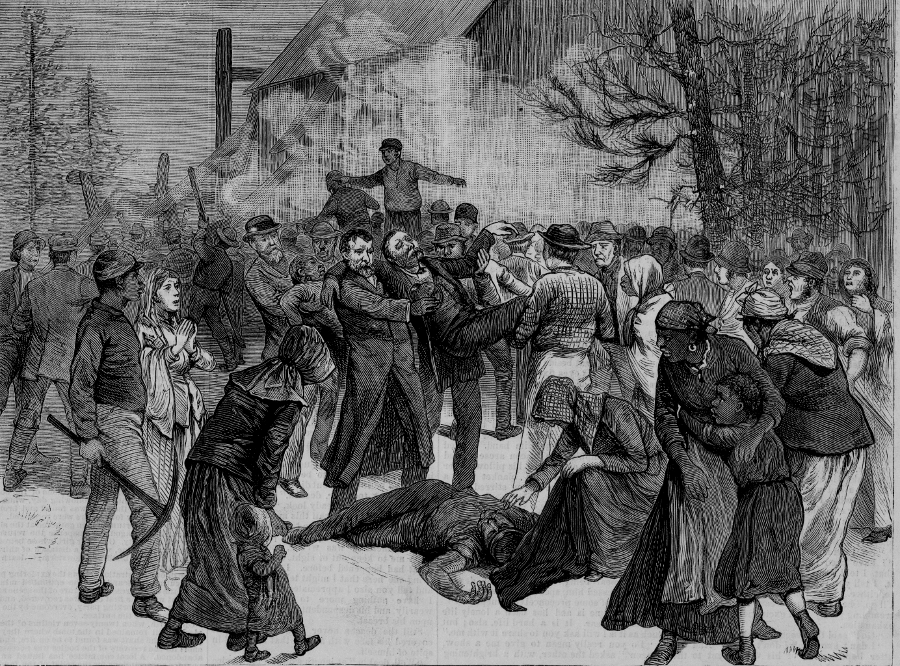

After the Civil War, the Midlothian mines struggled to stay in business. On April 3, 1867, an explosion in the Bright Hope pit, 850 feet deep, killed about 70 men - and four or five mules, as noted by the mine superintendent. Most mines closed in the 1880's, and the last coal mining ended in 1923.

Occasionally the residual material in mine waste dumps will catch fire by spontaneous combustion, or from a wildfire that passes across exposed waste coal. In 2023, two fires in tailings from the Beaver Slope Mine of the Bright Hope Coal Company in Chesterfield County required action by local firefighters. The Virginia Department of Energy Abandoned Mine Land team then covered the coal residue with gravel. Burying the coal was intended to isolate it from the air, preventing a new fire.

However, the tailings caught fire again in 2025 from spontaneous combustion. The mine had been active in 1877, back when it was harder to separate valuable coal from worthless shale and other rock. Once more the fire was extinguished with water, and inert material was mixed in with the coal waste in hopes of preventing spontaneous combustion again.4

37 men were killed in the 1882 explosion of a Midlothian coal mine, after methane accumulated in the poorly-ventilated tunnels

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, James Branch Cabell Library, The fatal explosion at the Midlothian Coal Mine

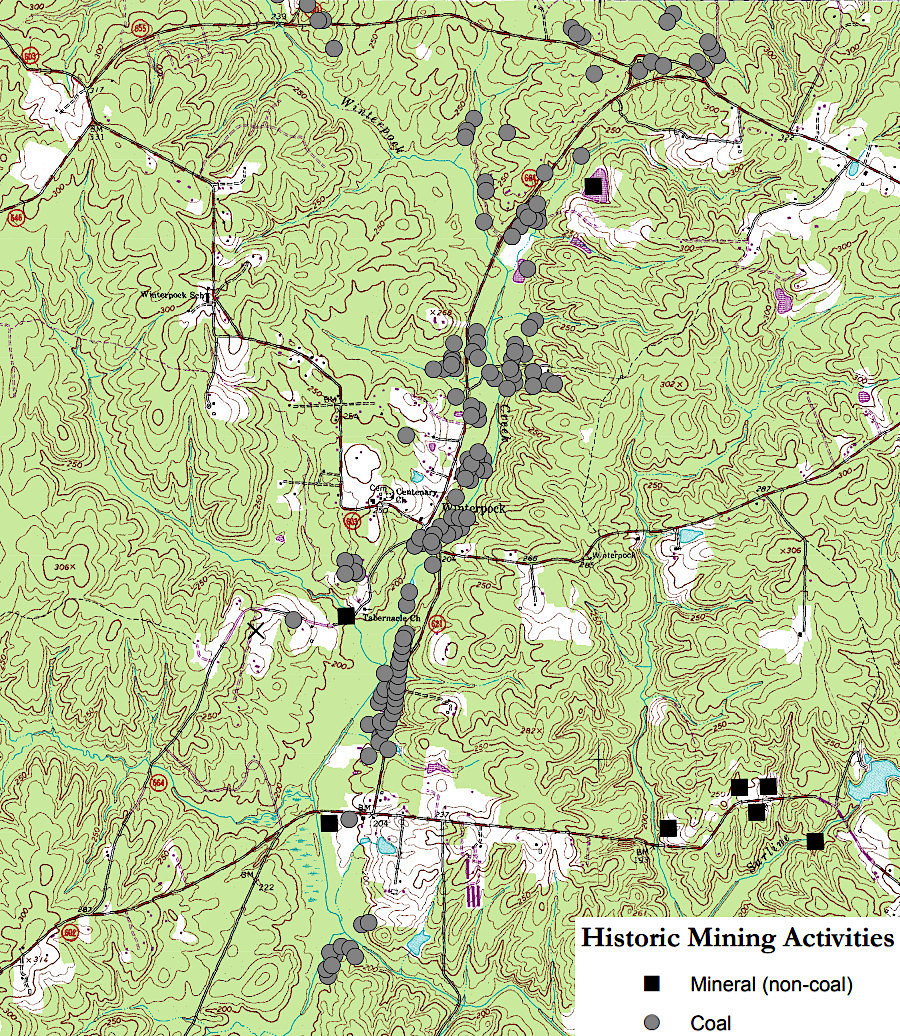

coal mines were common around Winterpock in Chesterfield County

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Abandoned Mine Land - Winterpock

Coal was also mined in Henrico County, west of Richmond.

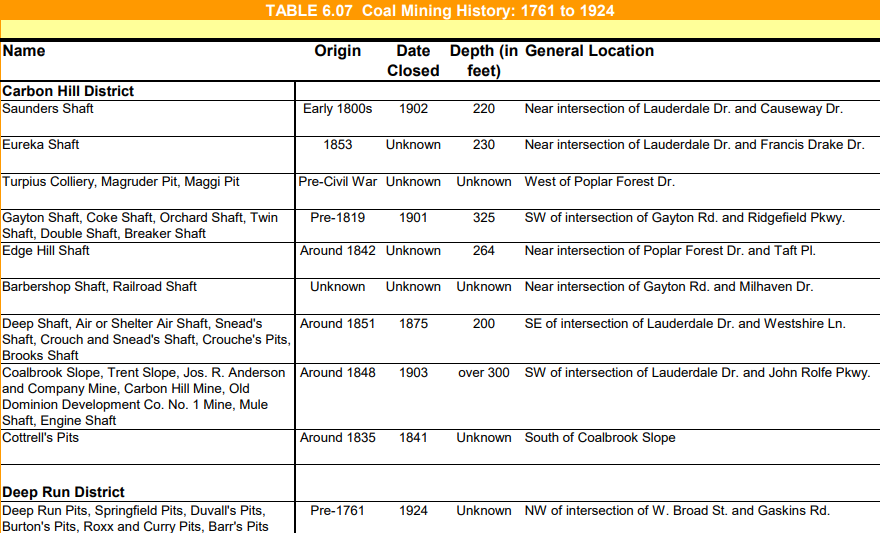

coal was mined from 10 locations in Henrico County prior to the Civil War

Source: Henrico County, Henrico County Historical Data Book

coal in Henrico County was west of Hungary Station on the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad

Source: National Archives, Map of the Vicinity of Richmond

the first Virginia coal mining was in Triassic Basin coal formations ("A") south and west of Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Geological map of the state of Virginia (1862)

Coal was mined from the Briery Creek basin near Prince Edward Courthouse in the 1840's. The Piedmont Coal Company mine opened in the Farmville basin in 1860. Virginians knew there was coal in the Appalachian Plateau, but those coal fields were not developed prior to the Civil War. Southwestern Virginia was remote with few customers to use the resource locally, and there was no transportation network to bring that coal to the customers living east of the Allegheny Front.5

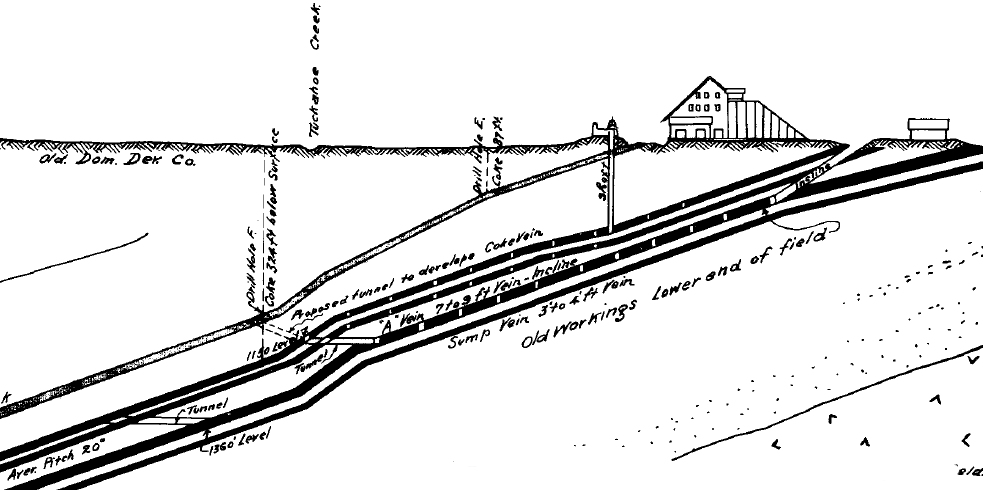

coal seams in Triassic Basin near Richmond, at Old Dominion Development Co. No. I Mine, angled downward

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Mining History Of The Richmond Coalfield Of Virginia

The coal fields of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province had value. Managers of iron furnaces in the Valley and Ridge province relied upon locally-produced charcoal, created from partially-burned wood, until after the Civil War. The Chesapeake & Western Railroad was extended west to the Dora coal field, near North River Gap in Rockingham County, but the small deposits east of the Allegheny Front were too small to support large-scale industrialization.

coal was mined from small fields east of the Allegheny Front

Source: Virginia Geological Survey, The Valley Coal Fields of Virginia (Figure 1)

Theoretically the iron producers west of the Blue Ridge could have obtained coal from Chesterfield and Henrico counties, transporting it from east of the Blue Ridge to the iron furnaces in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. However, the cost of transporting coal from the Triassic Basin across the mountains were too high.

It would have been uneconomic to purchase coal from the Richmond-area mines, ship the coal up the James River on the canal boats, and finally haul the coal by wagon to furnaces in the Shenandoah Valley or in the Great Valley south of the James River. Charcoal had lower energy per pound that coal and more baskets of charcoal had to be added to heat an iron furnace, but charcoal could be produced from the abundant nearby forests and delivered to an iron furnace at lower cost than Triassic Basin coal.

Mines in Montgomery County did ship coal by rail to Hampton Roads, after the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad provided a connection in the 1850's. Tradition holds that the coal from the Merrimac Mine on Price Mountain, between Christiansburg and Blacksburg, traveled all the way to Portsmouth and fueled the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia, built from the hull of the USS Merrimac. The first battle between ironclad ships, the Confederate CSS Virginia (Merrimac) and the Union Monitor, was also the first battle in the United States between warships fueled exclusively by coal.

coal outcrop near Mountain Lake in Giles County

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Northern financiers supported the extension of Virginia railroads into the timber-rich and coal-rich mountains of southwestern Virginia. The Norfolk and Western Railroad built a line up the New River Valley, and in 1882 reached Pocahontas in Tazewell County. The ability to ship heavy products to market by rail spurred land sales to corporations, followed by economic development and population growth on the Appalachian Plateau. Many of the profits were exported to Northern cities along with the timber and coal, limiting the standard of living for the average resident in the coal region.

an 1880 map of coal mining regions shows that Appalachian Plateau coal resources were not developed yet

Source: Library of Congress, "Scribner's Statistical Atlas of the United States," Plate 141: Mining (Coal)

The quality and quantity of the coal justified the extension of rail lines into many Appalachian "hollows." The Pocahontas Mine in Tazewell County had a seam of high-quality coal 13 feet thick, making it unusually easy to mine. By World War I, after the Norfolk and Western railroad built a rail line down the New River from Radford, then through West Virginia to the coal fields, the Pocahontas Mine became a major supplier of coal for the Navy.

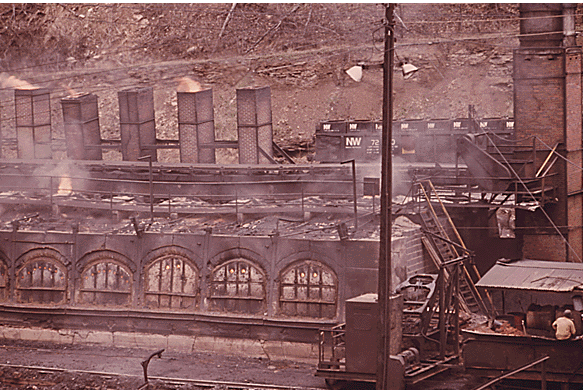

coal was first mined in Virginia from the Richmond, Briery Creek, and Farmville basins, up to fifty years before the Appalachian coal fields were developed

Source: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2004-1283, Geology and Energy Resources of the Triassic Basins of Northern Virginia

The role of coal has been critical in shaping the growth of Southwest Virginia for over a century. The Appalachian coal fields had national and international significance once they were developed in the 1880's, but the region has alternated between boom and bust economic cycles.

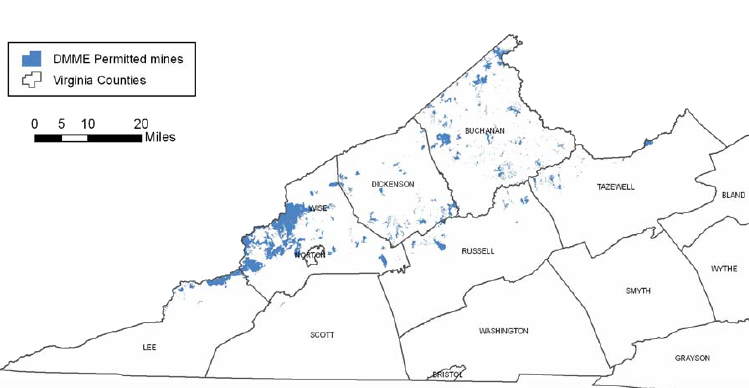

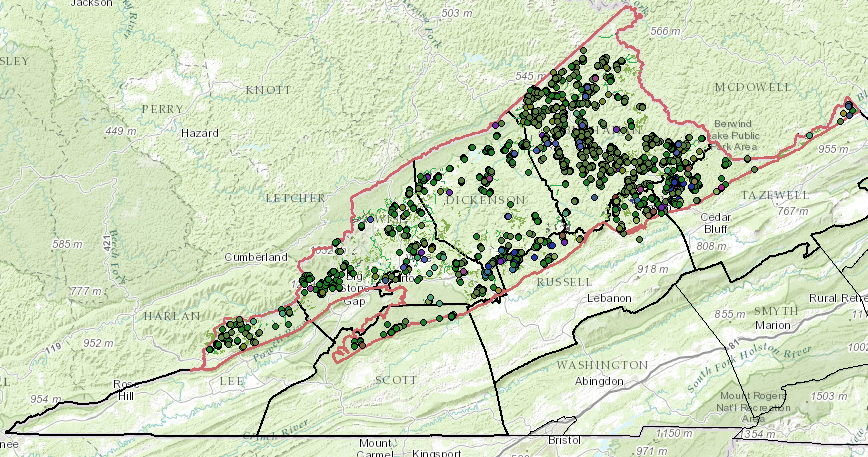

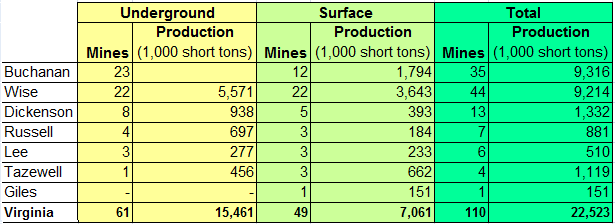

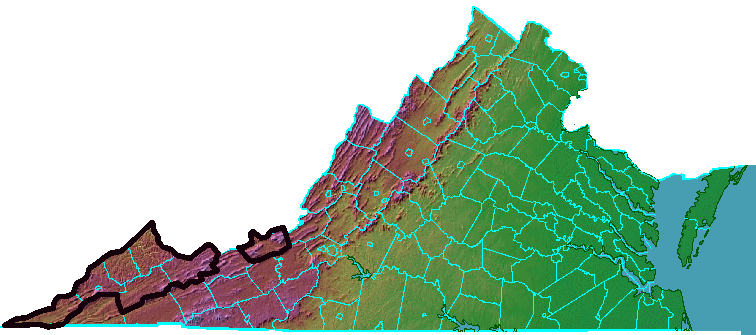

coal mines are concentrated in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties, but also located on that portion of the Appalachian Plateau that extends into Lee, Russell, and Tazewell counties

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Elk Restoration and Management Options for Southwest Virginia (Figure 4)

The demand for coal surged in the 1880's when the Industrial Revolution transformed the United States economy and railroads made it possible to ship the bulky coal to factories in the Northeast and in the Ohio River watershed. The Norfolk and Western Railroad, and later the Virginian Railroad, specialized in carrying coal to Norfolk. The Chesapeake and Ohio developed Newport News as a coal export port, and later built a trestle on the Richmond waterfront to bypass street crossings and speed delivery of the coal.

Roanoke blossomed to service the railroad traffic, and grew so quickly it was called the Magic City. Railroad jobs also led to development of towns on the Appalachian Plateau such as Dante, St. Paul, and Appalachia. East of the Blue Ridge, the coal-hauling business stimulated development at Crewe and Victoria with roundhouses, turntables, facilities for supplying coal and water to steam locomotives.

the towns of Crewe and Victoria are far from the coal fields, but owe their growth to that resource

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A century later in the 1980's, demand for coal from Appalachian mines had dropped significantly. Clean Air Act requirements led to a switch to low-sulfur coal, which was available from Powder River Basin in Wyoming. With the exhaustion of easy-to-mine coalbeds, the supply of low-cost coal from Virginia dropped. Underground mining, even with longwall machinery and other technology, was too expensive compared to strip mines in other regions. Appalachian strip mines were able to extract coal from seams near the surface, but the visual and environmental impacts of mountaintop removal created a public backlash.

coal miners in Tazewell County in 1974, with shifts preparing to go underground and emerging from the mine

Source: National Archives, Miners Waiting To Start Their 4 P.M. To Midnight Shift At Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company #4 Near Richlands, Virginia and Miners Just Leaving The Elevator Shaft Of Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 Near Richlands, Virginia At 4 P.M

Many of the trains still carrying coal to Newport News and Norfolk carry metallurgical ("met") coal. Overseas customers use it to fuel steel mills in particular.

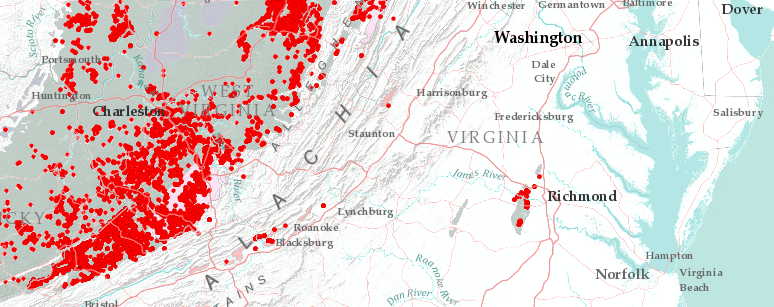

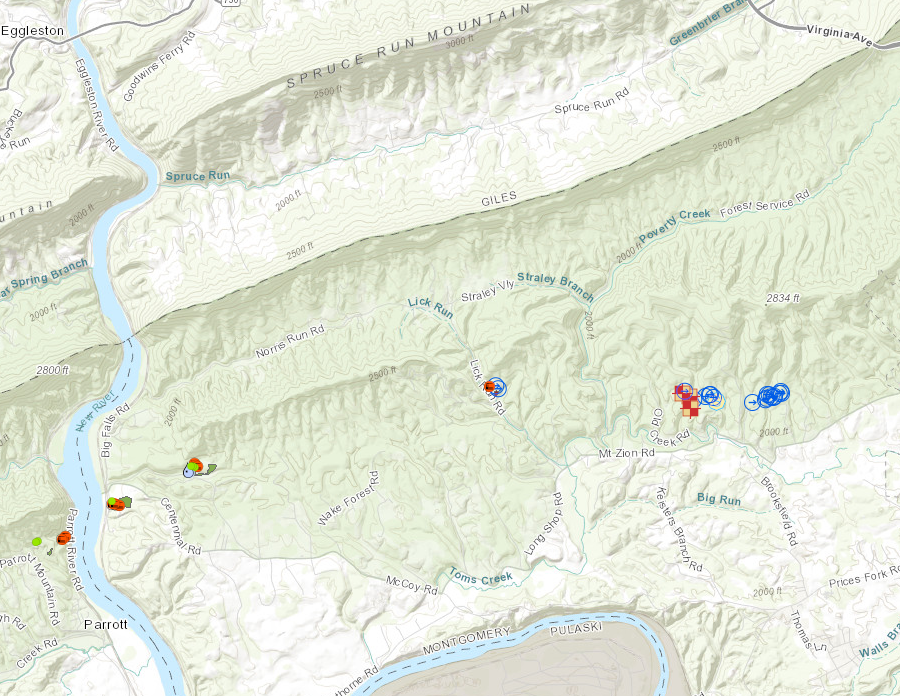

abandoned mine lands in Virginia include coal mines near Richmond, Harrisonburg, and Blacksburg, as well as in the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Office of Surface Mining - Abandoned Mine Land Inventory System, e-AMLIS

most abandoned mines in Virginia are located in the Appalachian Plateau, reflecting coal mining in the century before the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act was passed in 1977

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Flexviewer page

The coal fields and the oil/gas fields in Virginia are concentrated in the southwestern part of the state, and the Virginia Department of Mines, Mineral and Energy used to maintain multiple offices in the region. As mining activity declines, offices in Keen Mountain (Buchanan County) and Abingdon (Washington County) were consolidated with the offices in Lebanon (Russell County) in 2009. A separate office still remains at Big Stone Gap (in Wise County).

The Southwest Virginia economy is still vulnerable to "bust" as well as "boom," but some Virginia coal mines are still operating. Mine owners have expressed concerns that there will be too few trained miners if demand increased. Many children of miners have moved away or chosen other lines of work, and new hires will need formal training in coal mining.

Virginia's coal mines are all in the Appalachian Plateau, in a handful of southwestern counties

Source: Department of Energy Annual Coal Report, Coal production and number of mines by State, County, and mine type, 2011

For the long term, the Department of Energy predicts that increased demand for coal will be met by other regions. Even if a "clean coal" process could be developed for using coal to meet increased demand for electricity, Virginia's coal fields are not likely to see a major jump in production. Demand for thermal (vs. metallurgical) coal will be met by increased mining in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, or in the Indiana/Illinois/Western Kentucky coal fields.6

predicted growth in coal output to year 2030, showing how production from Appalachian fields is predicted to decline and affect Buchanan, Wise, and Dickinson counties in particular

Source: Department of Energy's Annual Energy Outlook 2008 with Projections to 2030

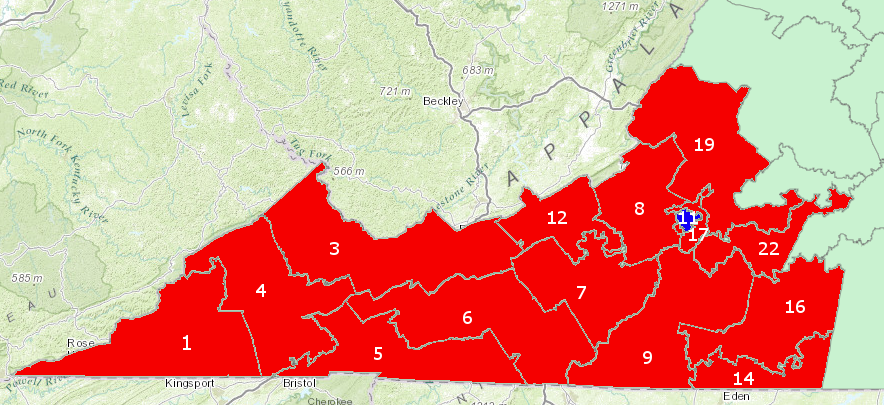

The decline of the coal industry in southwestern Virginia has affected both the economy and the politics of the region. The culture of the region remained focused on coal mining, even as the number of people employed in the industry has declined substantially.

The loss of unionized miners has reduced the strength of the Democratic Party in the region, which now depends upon urban voters to win statewide elections. Republican candidates in southwestern Virginia have capitalized on rural voter's concerns about social issues such as gun control and concerns about the size and power of government, and also benefited from Republican control of the process for redrawing boundaries of House of Delegates districts after the 2010 election.

Rick Boucher, who had won 19 elections as a Democrat to represent the "Fighting Ninth" congressional district, was defeated by a Republican opponent in 2010. By 2014, Republicans controlled every seat in the state legislature from the region except for one state senator's district. When State Senator Phillip Puckett resigned in 2014, voters chose a Republican to replace him. That switched control of the State Senate to the Republican Party, which then successfully blocked key initiatives by Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe (such as expanding access to Medicaid as part of "Obamacare") for the rest of his term.7

in 2013, only the 11th District (City of Roanoke) elected a Democrat to serve in the House of Delegates in the General Assembly

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (with 2014 Virginia House of Delegates layer from Virginia Geographic Information Network)

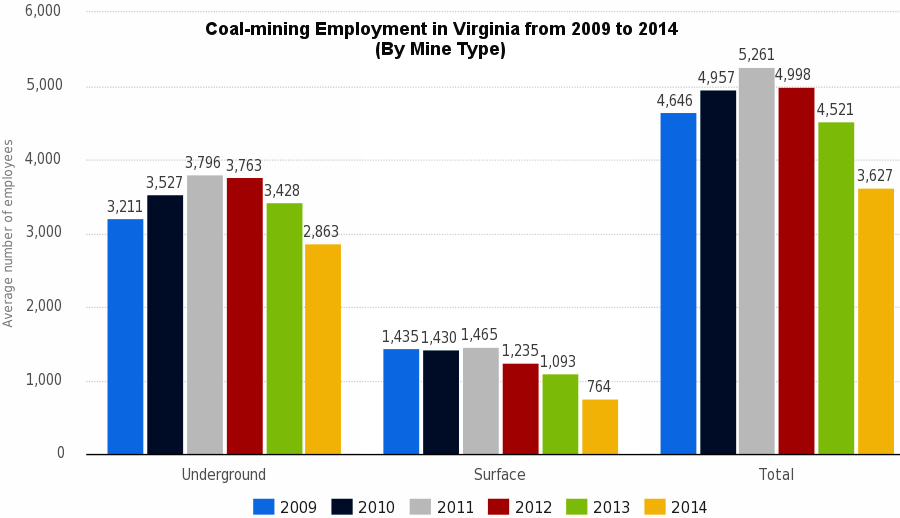

In the 2012 elections, the Republican Party accused the Obama Administration of conducting a "War on Coal" in in the southwestern part of Virginia. An October, 2012 rally in Grundy drew 5,500 people - when the total population in Buchanan County was less than 24,000, and there were only 5,000 coal miners in Virginia (a 50% drop since 1990).8

"the small number of coal miners have an outsized political influence because there are few other high-wage jobs in Southwestern Virginia

Map Source: Statistica, Coal-mining employment in Virginia from 2009 to 2014, by mine type

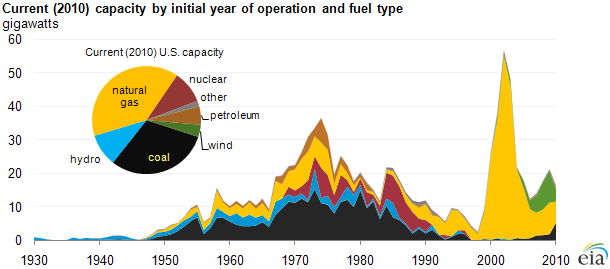

A major justification for that partisan claim was the decision by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant, and to issue other regulations that could be a "train wreck" for coal-fired power plants. However, one of the greatest long-term threats to coal was not political, but economic. As described by the Congressional Research Service, the development of natural gas combined cycle technology in the 1990's offered an alternative, cost-effective way to generate electricity at lower cost than maintaining old coal-fired power plants:9

since the 1990's, most new power plants have been fueled by natural gas or wind rather than coal

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Today in Energy, Age of electric power generators varies widely (June 16, 2011)

Some Federal regulations affect the cost of mining coal, such as Mine Health Safety Administration mandates to require effective ventilation systems to minimize the potential of methane gas explosions. After 1977, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) has imposed a fee on active mines in order to generate funds to reclaim abandoned mines.

For current coal mines, SMCRA requires coal mining companies to restore the approximate original contour of the land surface after strip mining is concluded. There is an exception for mountaintop removal operations. Operators can reshape the original topography of the site to fill valleys with the overburden removed from above the coal seam and create a level plateau of a gently rolling contour with no "highwalls."10

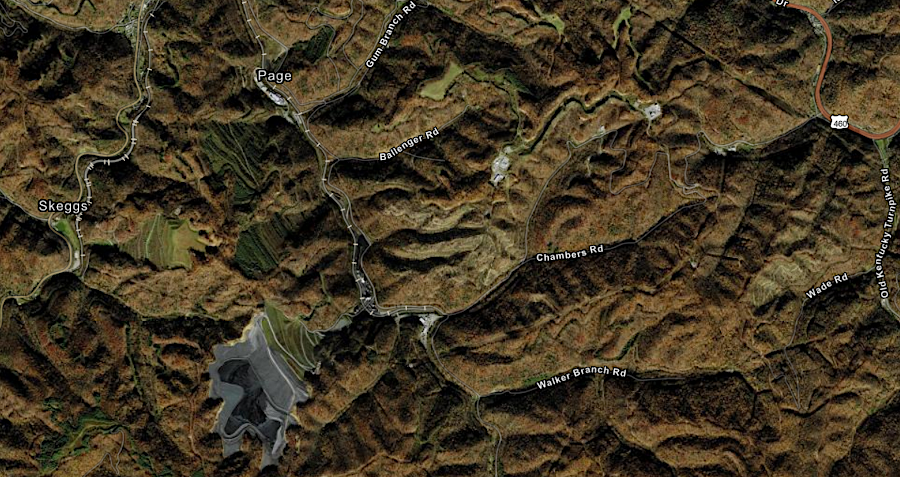

mountaintop removal has transformed the landscape in the Southwestern Coal Region, as in Wise County next to the Kentucky border

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Division of Mined Land Reclamation (DMLR) Flexviewer page

The EPA regulations regarding air quality and coal ash disposal have a substantial impact on the cost of burning "steam coal" to create electricity. "Met" (metallurgical purposes) coal is mined for making steel rather than electricity, and most is exported through ports at Hampton Roads - so the EPA regulations will have little impact on the "met" coal business.

Most Virginia mines operate for a short period until thin seams of economically-recoverable coal have been removed through the room-and-pillar method. The Buchanan Mine, near Mavisdale, is an exception, and celebrated its 30th anniversary of operations in 2013. It was the only Virginia mine using the longwall method to extract coal from the thick, highly-valuable Pocahontas 3 seam.

The need to vent methane to prevent explosions in the mine helped trigger the development of coal bed methane, which became a high-value energy resource in the Buchanan Coalfield. In the early 1990's, the General Assembly passed legislation to clarify ownership and royalty payments for coal bed methane. Consol then built a 50-mile pipeline from Buchanan to West Virginia, and later additional pipelines, in order to ship the natural gas through the interstate pipeline system.11

evidence of longwall mining of the Pocahontas 3 coal seam underground at the Buchanan Mine is

far less visible on the surface, compared to strip mining operations

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Vansant and Keen Mountain 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle maps (Revision 1, 2013)

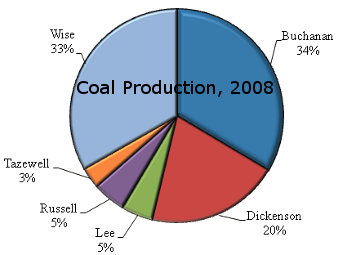

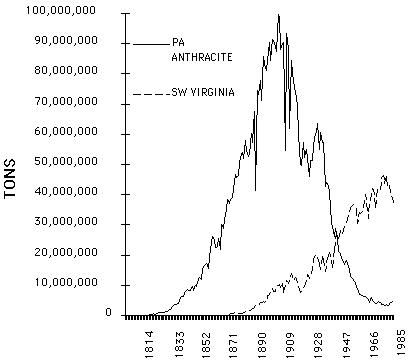

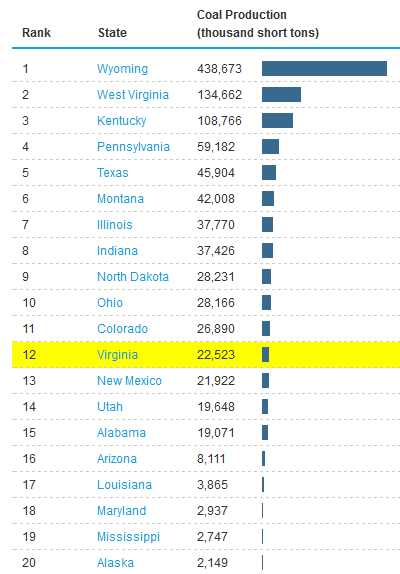

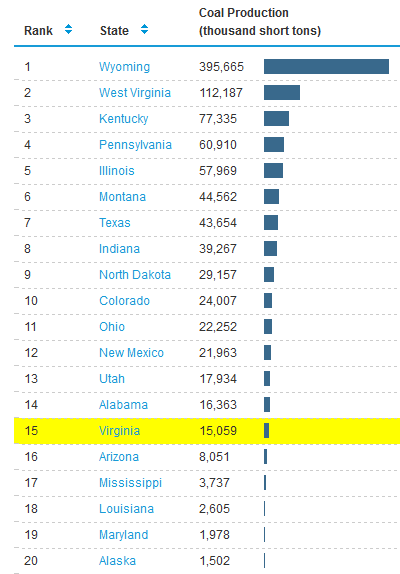

Of the 25 coal-producing states, Virginia was in the middle for tonnage of production in 2011. Wyoming mined over 20 times as much coal as Virginia. Both West Virginia and Kentucky produced over 5 times as much coal as Virginia. In 2011, the 49 surface mines in Virginia produced 55% of the state's coal, while 61 underground mines produced the remaining 45% - but those statistics vary significantly each year, as companies react to market demand and cost of extraction by opening/closing individual mines.12

commercial coal production commenced much later in Virginia than in Pennsylvania, and Virginia peaked at a little less than half of the maximum production for Pennsylvania anthracite

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), A Predictive Production Rate Life-Cycle Model for Southwestern Virginia Coalfields (USGS Circular 1147, Figure 4)

The same statistics from the US Energy Information Administration showed that Virginia's mines were relatively small producers in 2011, averaging just slightly over 200,000 short tons/mine. In 2011, the 110 operating coal mines in Virginia produced less coal than the 10 mines in Colorado.

Production/mine is much higher at surface mines. Only Virginia and West Virginia had more underground than surface mines, and only three states (West Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania) had more underground mines than Virginia.

between 2011-2014, Virginia's coal production dropped below three more states

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Rankings: Coal Production, 2011 and Coal Production, 2014

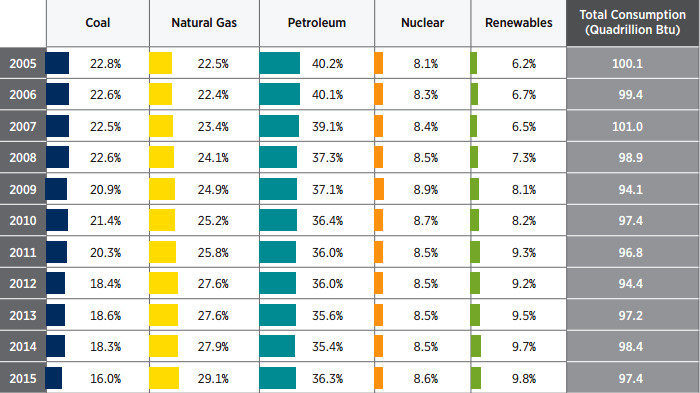

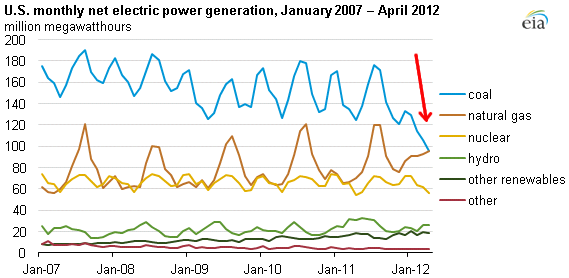

The US Energy Information Administration has noted that 90% of coal mined in the United States was used to generate electricity - but the competition from natural gas was increasing:13

the percentage of energy generated from coal dropped steadily after 2005

Source: US Department of Energy, 2015 Renewable Energy Data Book (U.S. Energy Consumption by Energy Source)

The last coal-fired power plant built in Virginia, the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County, started producing electricity in 2012. Since then, utilities have chosen natural gas rather than coal for new power plants, such as Dominion's 1,358-megawatt, $1.3 billion Brunswick County Power Station.

Even in southwestern Virginia's "coal country," industrial facilities are switching from coal to gas. The shift reduces operating costs; burning gas is cheaper that burning coal.

In 2013, the Celanese Corporation in Giles County (which produces a key material for cigarette filters and ink reservoirs for fiber-tip pens) announced plans to replace seven coal-fired boilers with six natural gas-fired boilers. The shift cost $150 million and, since 2015, natural gas has fueled a facility that had burned coal since 1939.14

by 2012, natural gas and coal had equal shares (32%) of the nationwide market for generating electricity

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Today in Energy, Monthly coal- and natural gas-fired generation equal for first time in April 2012 (July 6, 2012)

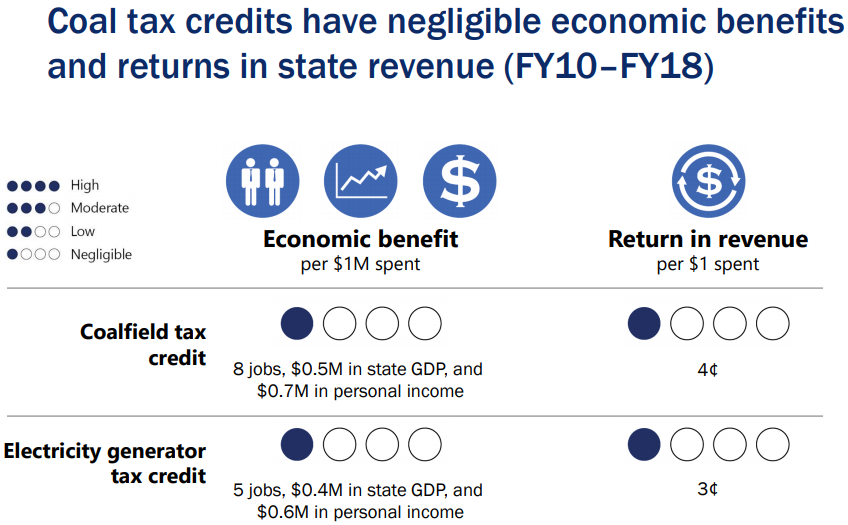

In 2021, the General Assembly eliminated special tax credits designed to encourage production of coal in Virginia. The Coalfield Employment Enhancement Tax Credit to incentivize mining coal in Virginia was created in 1996, and the Coal Employment and Production Incentive Tax Credit to purchase Virginia-mined coal to produce power was adopted in 2001. Both were proposed as regional economic development incentives to benefit Southwest Virginia.

A report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission in 2020 concluded that the $315 million in coal tax credits used between 2010-2018 had not been effective. Coal production in the state had peaked in 1990, and continued to decline. The thicker coal seams had been exhausted, and remaining reserves were geologically difficult and expensive to access despite the tax credits.

By 2022, 70% of the coal produced in Virginia was for metallurgical purposes. The Coalfield Employment Enhancement Tax Credit was restructured in 2018 so only metallurgical coal mining and coalbed methane production were eligible.

Though experiments in manufacturing steel were testing the use of electric currents and hydrogen rather than metallurgical coal to smelt iron ore, the Buchanan Mine Complex in Buchanan County was expected to remain profitable. Mining started there in 1983, and it grew into the largest metallurgical coal mine in Virginia. By 2022, 25% of Virginia's remaining 2,000 coal miners were employed there and the Buchanan Mine Complex was producing 40% of Virginia's coal.

the Buchanan Mine is underground, but a tailings pile is visible on the surface

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2022, Coronado Global Resources announced plans to invest almost $170 million to expand the mine and produce more metallurgical coal. Access to Russian coal had been limited by the war in Ukraine, and the company projected increased demand for the pulverized coal injection (PCI) material used to manufacture steel.

By 2022, metallurgical coal was the only part of the coal business expected to receive significant new investment; the economic reason to purchase Virginia-mined coal for generating electricity was disappearing fast. Only the Virginia City Hybrid plant in Wise County was expected to continue to use Virginia-mined coal after 2025.15

coal tax credits provided negligible benefits as economic development incentives for Southwest Virginia

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Infrastructure and Regional Incentives (September 14, 2020)

Reclaiming the sites of former coal mines still creates jobs. In 1977, the US Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. It authorized collection of a fee on all operating coal mines, with revenues used to reclaim abandoned coal mines. In 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act appropriated additional funding. The Virginia Department of Energy, which had been receiving $3 to $4 million per year, projected that it would receive almost $23 million more each yar for the next 15 years. That would be sufficient to fund reclamation of 80% of the abandoned coal mines in Virginia.16

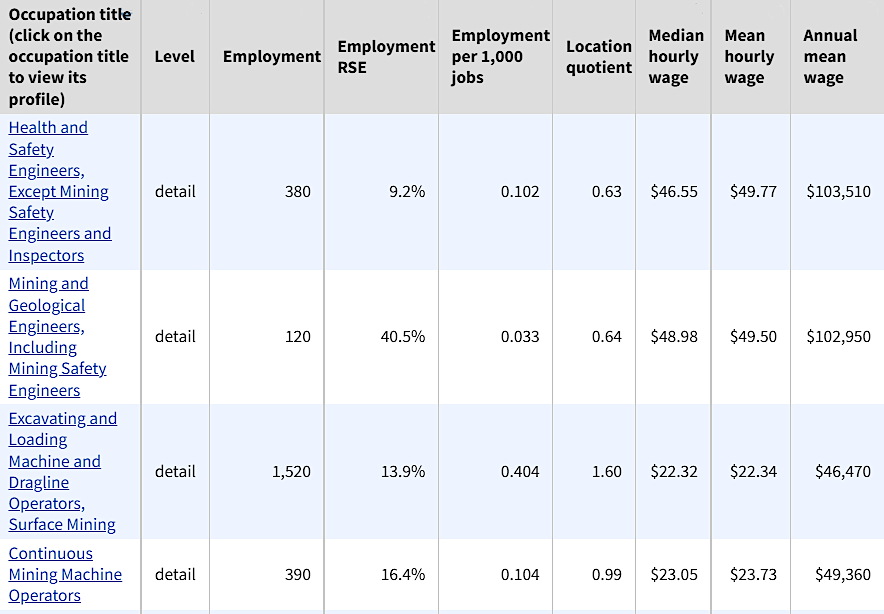

Coal mining offered the highest-paying jobs in the Appalachian Plateau counties of Southwest Virginia. In 2021, a machine operator in Dickinson County earned $46,470/year when the average income of an entire household in that county was just $29,932/year. New jobs for reclamation of coal mines might require skilled machine operators, but only until reclamation is completed. If solar panels are installed at old mine sites, there would be jobs during the construction of the utility-scale solar facilities -but few jobs for operations and maintenance.

There is a possibility that coal country in Southwestern Virginia could attract Amazon, Microsoft, QTS< and other data center companies to build facilities next to the sources of solar power. However, after construction there would be few jobs for operations and maintenance in those facilities.17

Mining metallurgical coal could provide the highest-paying jobs in coal country for decades, until steel manufacturing shifts away from coal and begins to use hydrogen or other "green" sources of energy.

in 2021, coal mining paid more than most other jobs in Southwest Virginia

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2021 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates

Virginia

mining in the 1800's was hard physical labor, in tight quarters with minimal light

Source: University of North Carolina, The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (1875)

abandoned coal mines near Blacksburg

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Virginia Abandoned Coal Mine Feature Inventory

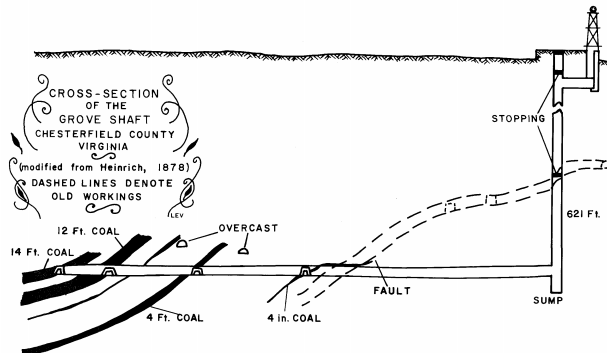

coal deposits were mined in Triassic Basin by sinking vertical shafts, then digging horizontally to intercept different seams

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Mining History Of The Richmond Coalfield Of Virginia (Figure 21)

coal deposits in the Appalachian Plateau had been identified by the time of the French and Indian War, but hauling coal was expensive and large-scale commercial development did not occur until railroads were built after the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America (1774)

Source: Library of Congress, The story of coal (~1920)