wooden saplings provided structural support for bark and reed exteriors of Native American houses in Virginia

wooden saplings provided structural support for bark and reed exteriors of Native American houses in Virginia

For 15,000 years, shelters in Virginia were constructed from local organic materials. Frames were built from saplings, then covered with tree bark or reeds from wetlands. Though Native Americans manufactured pottery from clay, they did not make bricks.

The early English colonists built structures from readily-available wood and reeds, and added clay to the mix. The palisade of the fort at Jamestown was constructed from tree trunks. Structures inside the fort were made from strips of wood covered with clay, known as "wattle and daub." Local reeds were used to create thatch roofs for those structures; even the first church at Jamestown was built with wood, clay, and reeds for the roof.

early structures at Jamestown were built from clay and woven strips of wood (wattle-and-daub), as shown in this reconstruction at Jamestown Settlement

The English who settled in Virginia in the early 1600's:1

In 1686, a Frenchman observed in the newly settled region of Stafford County:2

The first clay bricks in Virginia were used to build a baking oven at Jamestown. Those bricks were probably brought on ships from England.

In 1638, the first brick house in Virginia was built in Jamestown by Richard Kemp, Secretary of the colony. Structure 44, marked today by the ruins of the Ambler family's later mansion, was built before the brick church in 1639.

The oldest brick house still standing in Virginia was built in 1665 by Arthur Allen in Surry County. It was known originally as Arthur Allen's Brick House, and today as Bacon's Castle. (There is no evidence that Nathaniel Bacon ever visited the site during his 1676 rebellion, but his followers occupied it for three months.)3

Starting in the mid-1700's, gentry on the Northern Neck constructed mansion houses from brick, such as Robert Carter's family home at Sabine Hall. This showed the importance of the family through the permanence (and cost) of the family home. Clay was readily available, but there were few outcrops of stone suitable for building purposes on the Coastal Plain. Where the stone was available, it was soft sandstone, subject to crumbling in the weather.

The vestry members of Pohick and Aquia churches added stone corners known as "quoins" to make their churches appear more magnificent. George Washington added sand to the paint covering his wood-sided house. He had blocks of wood shaped to look like stone. They were nailed together to form siding for the exterior of Mount Vernon and coated with oil primer. After the primer dried, a layer of oil paint was added. Before the layer of oil paint could dry, sand was tossed into it by hand. The sand stuck to the thick coat of paint, creating the appearance of stone and making Mount Vernon appear more impressive.

Aquia sandstone was used on the second Pohick Church built in 1669-74 to provide architectural accents on the corners and around the doors

When colonists wanted to create structures that demonstrated power and wealth, they built out of brick. After Charles II was restored to the throne, his appointee Governor Berkeley returned to the colony in 1662 with plans to build 32 brick houses at Jamestown. Each house was to be 800 square feet, with roofs 18 feet high. Governor Berkeley also built a brick statehouse. That statehouse was burned during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, but its replacement was roofed with tile and slate before that structure burned in 1698.4

colonial Virginians collected oyster shells, then heated them to create mortar to tie bricks together

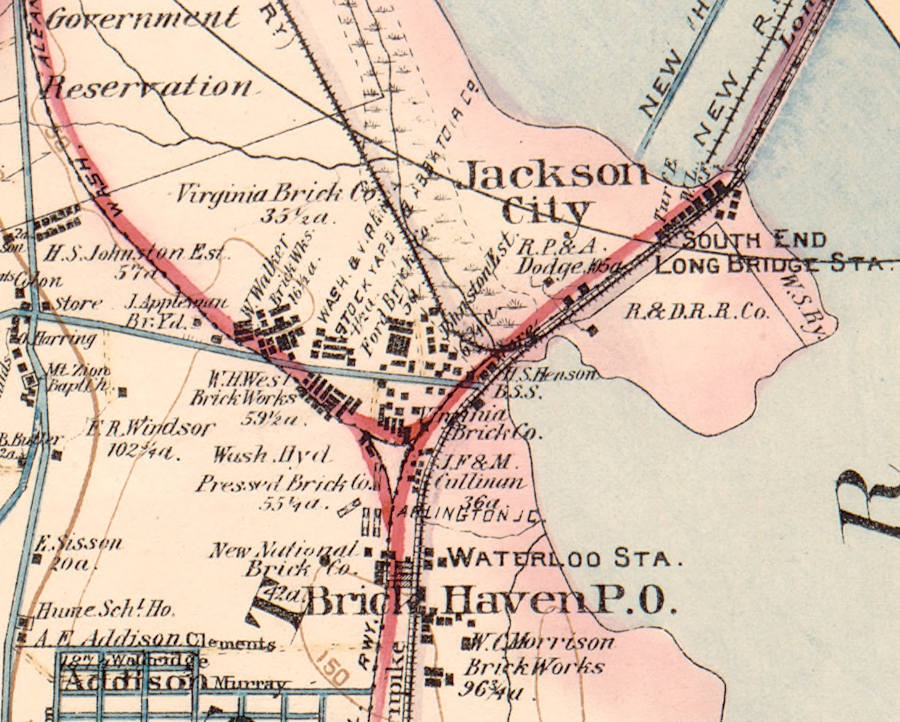

brick manufacturing was a major business in Alexandria (Arlington) County in the early 1900's

Source: Library of Congress, Baist's map of the vicinity of Washington D.C. (1904)

Little stone was used in the first brick structures, other than river cobbles for foundations and floors. For colonists at Jamestown, there were no outcrops of exposed stone other than the hard granite at the Fall Line rapids.

The bedrock in Tidewater Virginia is buried under thick layers of sediment which eroded off the ancestral Appalachian Mountains. Those sediments were mobilized and re-desposited in sedimentary formations during periods of high sea level. Today the sediments, particularly the lowest and oldest Potomac Formation, store ancient rainfall in underground aquifers.

The formations at the surface were never compressed sufficiently to be consolidated into hard stone. In the Coastal Plain, basements are excavated and large quarries operate with backhoes and bulldozers. There is rarely any need for drilling and blasting at construction projects east of I-95.

The depth of sediments to bedrock is thinnest next to the Fall Line and gets thicker towards the edge of the Continental Shelf. Underneath Williamsburg, Coastal Plain formations are thousands of feet deep. Native Americans living east of the Fall Line used river cobbles to make stone tools and traded for high-quality stone imported from the Piedmont, Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, and Appalachian Plateau physiographic regions. Colonial settlers imported stone from Europe.

The floors of the Catholic church constructed around 1667 at St. Mary's, Maryland and the Maryland State House built in 1676 were paved with stone brought from England. The stone cargo may have doubles as ballast for ships making the trans-Atlantic trip.

Both the first and second Capitol buildings in Williamsburg used pavers imported from quarries on the Isle of Purbeck or nearby in southern England. The limestone was 140 million years old.

Robert "King" Carter, the wealthiest man in Virginia at the time, was involved in that project. He was also responsible for the completion of the second Lancaster County courthouse at the start of the 1700's, and ordered pavers from England for that structure. County taxpayers were responsible for the costs of building that new courthouse.

The Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, constructed between 1706-1722, used Purbeck limestone as well as 600,000 bricks. The unique stone floor in the entrance hall, with black and white squares, was designed to impress everyone with the authority and power of the royal governor.

Robert "King" Carter displayed his wealth at his Corotoman mansion by importing pavers from Purbeck quarries in 1721. He ordered over 2,000 square feet of dressed stone from the Purbeck quarries in 1721, as paleontologists demonstrated by a unique combination of clam and oyster fossils in the rock.

Some of the pavers never reached Virginia. Roughly 15% of the stone on the ship was tossed overboard during a storm, suggesting it was loaded in a cargo hold rather than being used as ballast. Those pavers still lie somewhere on the bottom on the Atlantic Ocean.

After Corrotoman burned in 1729, Carter focused on building a new church in Lancaster County rather than rebuilding his mansion. He repurposed the stone that covered his basement floor and used it to make distinctive aisles in the new Christ Church. For nearly 300 years, everyone coming to Sunday services there had gotten a visual reminder of Carter's wealth and power.

Other structures in Lancaster County also reutilized the bricks and stone pavers from the ruins of the mansion house. Of the original 700 or so limestone pavers used at Corotoman, only 57 flat stones remained in place when archeologists excavated the ruins in the 1970's. The floor of Christ Church has 352 of what are believed to be original Corotoman pavers.

In the 1700's, a dozen parish churches imported "Bristol stone" or "Portland stone" from quarries in southern England. Those limestone pavers were placed in their aisles between the pews.5

The first local stone for colonial builders in the 1700's came from outcrops of Aquia sandstone on the western edge of the Coastal Plain. Particles in the upper part of the Patapsco Formation of the Potomac Group wqere eroded from the Piedmont and western mountains, then deposited by rivers 110-97 million years ago. Overlying sediments (now washed away) provided enough heat and pressure to cement the particles together. Iron oxide brought with groundwater also served as a glue.

The upper Patapsco Formation was lithified sufficiently to serve as "dimension stone" cut to a preferred size and as steps, but lacks the durability of bricks. The cream- and gray-colored sandstone with reddish streaks of iron oxide was used primarily to provide architectural details on building exteriors. Old steps made from Aquia sandstone show erosion from foot traffic.

Starting around 1730, wealthy plantation owners in Tidewater added "quoins" of Aquia sandstone to edges of red brick houses and churches. The ability to afford the contrasting colors made a clear social statement. Aquia sandstone, rather than imported Portland limestone, was used at Christ Church in Lancaster County to decorate the exteriors of windows and for steps.

The Brent family began quarrying sandstone from outcrops on Aquia Creek at the end of the 1600's, initially for tombstones. Another source of Aquia sandstone was Freestone Point, now part of Leesylvania State Park in Prince William County. Freestone Point got its name because the rock there was soft enough to be quarried easily into desired shapes:

Chunks of sedimentary rock excavated from the ground could be cut with iron tools into desired shapes and sizes, similar to Portland limestone in England. Freestone Point's location next to the river channel made it easy to transport heavy stone blocks from the quarry to its final destination.

The most significant historical quarry in the Coastal Plain was developed on an island in Aquia Creek, where the quarried blocks could be transported via boat. Heavy blocks were carved out of Cretaceous sandstone outcrops of the Patuxent Formation, then transported by sled to the waterline. With great physical effort, the blocks were lifted into small boats. Those boats floated the stone out to deeper water, where the blocks were reloaded into larger boats which sailed up the Potomac River to Washington.

Mt. Airy (on left) was built from Triassic sandstone, while Sabine Hall (on right) was built using brick

Weems Ordinary (left) and Mt. Airy (on right) used local sandstone for quoins

Sabine Hall (left) and Stratford Hall relied upon brick, except there is a sandstone outbuilding at Stratford Hall

(click on images for larger pictures)

The Federal government purchased the Stafford County quarry from the Brent family in 1791; the site has been known as Government Island ever since. One acre was owned separately by a stone mason named Robert Steuart. He marked his property boundaries by carving "R S" in the soft stone.

Blocks carved out of Government Island sandstone were used to build the Executive Mansion (White House) and the US Capitol in Washington, DC. Aquia sandstone was also used in Aquia Church (Stafford County), Christ Church (Alexandria), and Pohick Church at Lorton (Fairfax County). Aquia sandstone decorated Governor Thomas Nelson's family home in Yorktown, George Washington's Mount Vernon, George Mason's Gunston Hall, John Carlyle's house in Alexandria, and Williams Ordinary in Dumfries. The sandstone was carried south to Princess Anne County (now Virginia Beach) for use in the foundations of the lighthouse at Cape Henry.

John Tayloe II used reddish iron-rich sandstone from the Northern Neck to build Mt. Airy and Menokin. He imported white Aquia sandstone from further up the Potomac River to accent the edges of his house with colorful quoins. Tayloe reversed the color scheme when he built Menokin for his daughter Rebecca and son-in-law Francis Lightfoot Lee. He used the red sandstone for the quoins and covering it with white plaster on the sides of that manor house.

The gatehouses originally built for the US Capitol in Washington, DC around 1827-29 were constructed from Aquia sandstone. Unlike the White House, they have not been protected by any coating. Their decayed appearance is obvious to tourists who note the structures at their current locations on Constitution Avenue, at 15th and 17th Streets.

Bulfinch gatehouse at West Entrance for US Capitol, now at 15th and Constitution Avenue

Stafford County bought the site in 2008, built bridges/trails/interpretive signs, and opened it as a public park. An adventure lab based on geocaching, with five different points of interest, was created there in 2020.6

The 100-130 million year old Cretaceous sandstone at Freestone Point and Government Island is barely lithified into rock, and is quite porous. In the winter, water that seeps into the stone can freeze, cracking the surface. To avoid that problem on the stone exterior of the new "Presidents House" in Washington, DC, a lime-based whitewash was applied. After the British burned the building in 1814, the White House was coated in white paint.7

George Washington could not afford stone for Mount Vernon, so he faked it. The wooden siding on the exterior is cut and painted so it appears to be constructed of stone. Washington experimented with techniques to ass sand to the paint, in order to create his desired look. Before the second coat of white paint could dry, workers threw sand onto the surface. When the paint dried, the sand particles provided the rough texture that looked like stone.8

painters tossed sand onto the wet surface of Mount Vernon in 2014, replicating George Washington's technique

Source: Mount Vernon, West Front FAQs

carved wood and sand in pant allowed George Washington to appear to have a house built from stone

Once colonial settlement reached the Piedmont, natural outcrops provided easy access to building stone. Potomac bluestone was quarried on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, as well as in Rock Creek Park in the District of Columbia.

About 30 Italian immigrants established "Little Italy/Littly Sicily" at one bluestone quarry, located now next to what is now the George Washington Memorial Parkway near Potomac Overlook Regional Park. The rock was barged across the Potomac River and used to construct buildings and roads in the District of Columbia.

That quarry-focused community thrived between 1910-1938, with a general store serving 30 residents. Black quarrymen from Westmoreland County hammered and drilled the bluestone there seasonally as well. Smoot Sand & Gravel shut down operations at the site in 1941. Two shacks were still occupied when the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission purchased the quarry in 1956 for constructing the Spout Run extension of the parkway. The homes of the last three quarrymen, by then in their 80's, were bulldozed and they were forced to move to a farm in Prince William County.9

In Richmond, granite quarries on Belle Isle provided building material for the locks of the James River and Kanawha Canal.

In the Culpeper Basin, red Triassic-age sandstone west of Centreville was quarried in the 1800's to create a stone bridge over Bull Run, a toll house on the Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike, and many other buildings. A Maryland quarry supplied that Triassic sandstone for the Smithsonian Castle on the National Mall and the locks for the Potowmack Canal at Great Falls, while Connecticut quarries supplied Triassic sandstone for the "brownstones" in New York City. Their brown color is a result of the rusting iron within the rock.10

Triassic sandstone was used to build a toll-collection station on the Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike, now the famous Stone House on the Manassas battlefield

Immigrants from Scandinavia into Delaware introduced the log cabin design to the Middle Atlantic. Early log cabins were built quickly on the frontier with a minimum of effort. Rather than spending rime to saw off the round edges of logs, mud was used to chink the gaps. Cabins built with rectangular, sawed-off logs (and occasionally some foundation stones to minimize decay) indicate that the location was more settled, with labor and time available to create a more-substantial structure.

mud was used between logs to block wind/water, and stone chimneys reduced the risk of fire

In the Shenandoah Valley, exposed limestone was carved into building blocks to construct solid houses such as Abram's Delight in Winchester.

After fire destroyed the first two wooden buildings used by Liberty Hall Academy in Lexington, the school constructed a limestone structure. Fire destroyed the interior in 1800, but two of the exterior walls are still standing. As the school morphed into what is now Washington and Lee University, new buildings were constructed of brick instead of limestone.

the limestone walls of Liberty Hall Academy still remain on the campus of Washington and Lee University

Further south in Blacksburg, the school now known as Virginia Tech struggled with the perception that it was a "second-rate vocational school" because its brick buildings resembled contemporary cotton mills and shoe factories.

In 1899, the school started building with blocks of dolomite (calcium and magnesium carbonate), colloquially known as "Hokie Stone." In the 1960's, new buildings were erected without the traditional Collegiate Gothic style and without a skin of Hokie Stone, but since then more-modern structures with the traditional Hokie Stone exteriors have hidden those inconsistent structures.

Virginia Tech's distinctive architectural style relies upon locally-quarried limestone known as Hokie stone

Source: Flickr, VBI (by pedrik)

Derring Hall is located on the site of the original quarry, which closed in 1953. Ironically, Derring Hall was built without Hokie Stone, during the era of modernist architecture. Cassell Coliseum, Cowgill, and Whittemore werree also bilt without limestone exteriors using the Gothic design.

In 2010, the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors mandated that new buildings must incorporate Hokie Stone, maintaining the signature architectural style of the campus. To guarantee a supply of stone at a reasonable price, the university purchased the 40-acre quarry that provides most of that building stone. It is blasted free from bedrock using black powder to minimize pulverizing the blocks, and to minimize noise and vibration impacts on adjacent residential properties.

Virginia Tech stoneworkers process all the raw material used to cover exteriors in Hokie stone, but 10-20% of the rock is purchased from a private quarry at Lusters Gate, to ensure the right mixture of blocks with light gray, darker gray, brown, and black colors:11

the Bland County Courthouse is brick, not limestone

local sandstone and limestone were used to build the Ayers mansion in Big Stone Gap (Wise County), now the Southwest Virginia Museum Historical State Park

brick buildings are not common in the commercial section of Big Stone Gap

the most significant public building in Big Stone Gap was built with limestone

stone building in downtown Leesburg

The largest building stones in Virginia were used to construct the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. Four artificial islands were created at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to anchor tunnels underneath the shipping channels. To protect the islands from erosion by normal currents and waves, and especially in storms, large granite boulders were placed around the edges to create a shield of rip-rap. "Red Oak" granite was excavated at the Kenbridge granite quarry in Lunenburg County:12

the rip-rap boulders protecting the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel came from Lunenburg County

Source: Flickr, Chesapeake Bay Bridge & Tunnel (by Bex)

In the Chesapeake Bay, the boulders were lifted off the barges and carefully placed on the bottom on the seabed, building a container wall that rose up ultimately above sea level:13

The large boulders proved to be a surprising problem in 2020. The islands for the tunnel below Thimble Shoals channel were being widened to accommodate a second tube, and the rip-rap had to be moved to allow for the Tunnel Boring Machine to start digging through soft soil. A coffer dam was planned to protect the island before relocating the boulders, but driving steel pilings through the rip-rap to create the coffer dam wall turned out to be a challenge. The Red Oak granite boulders were thicker and deeper than anticipated, and a Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel official described the problem succinctly:134

driving steel pilings through the rip-rap boulders was like "trying to drive a nail through granite rock"

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge & Tunnel, CBBT Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel's Temporary Trestle

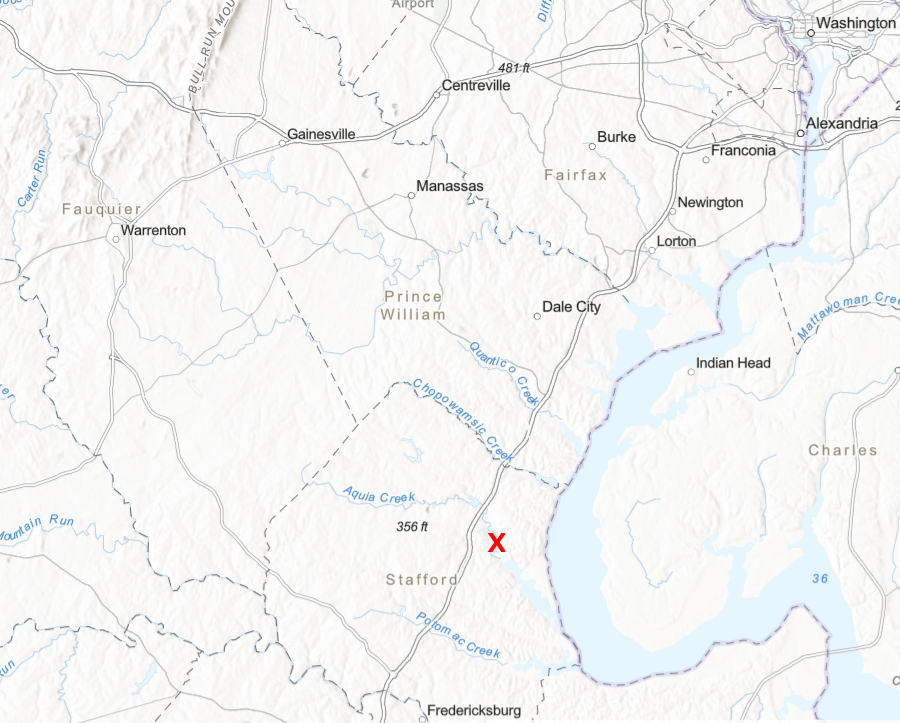

Government Island (Red X) was on a navigable section of Aquia Creek, facilitating transport of stone to Washington DC for building the White House and Capitol

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

log cabins were frontier structures, easy to build with abundant timber

(click on images for larger pictures)

one of the quarries used for building stone at Virginia Tech is east of campus

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Hokie Stone at Virginia Tech is not just one color of gray

(click on images for larger pictures)

Buckingham Slate is used for signs in the area around Buckingham County

In 2013, Colonial Williamsburg made replacement bricks for repairing the 17th Century tower of the church at Jamestown

church tower at Jamestown, built before 1702 and restored in 2014

(church in background is a 1907 re-creation)