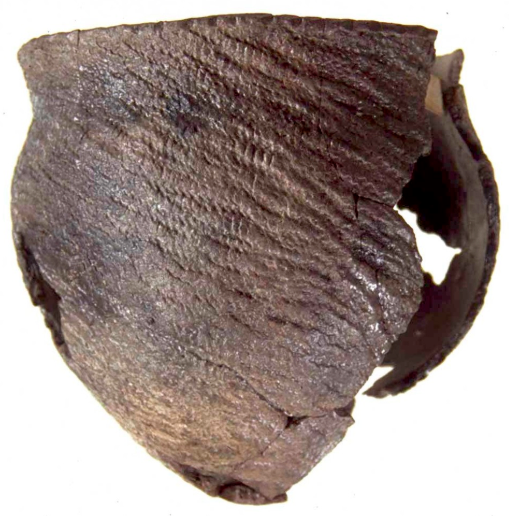

the Pamunkey in the 1900's made pottery in the traditional Woodland style

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Jar made in Late Woodland archaeological style

the Pamunkey in the 1900's made pottery in the traditional Woodland style

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Jar made in Late Woodland archaeological style

Early humans may have noticed that clay could be baked by fire into a hard shape, but the oldest known intentional pottery is a clay figurine representing a woman from 30,000 years ago (28,000 BCE). Pots in China have been dated to 16,000-15,000 BCE. The development of small flake tools (microliths) and grinding slab stones, along with wide use of pottery by 11,000 BCE, enabled people to expand the range of wild plants that could be utilized for food long before the development of agriculture. Natural glazing from the smoke in a fire made some pots waterproof, before the development of glazing technology.

Earliest pottery was made by drying clay in the sun or baking it in fires, sometimes in rudimentary kilns created by excavating small depressions in the ground. Such earthenware pottery was produced at temperatures below 1,000°C. Later, people in China invented high temperature kilns in which temperatures reached 1350°C to produce stoneware, and also created high-density porcelain made from kaolin clay.1

In the New World, pottery was developed independently in South and North America. The oldest archeological sites where South American pottery has been discovered are on the Columbia and Ecuador coasts, and date back to 3500-3000 BCE.2

Native Americans decorated their pottery in various ways, including stamping the wet clay before firing a pot

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Stamped Ceramic Sherds

Clay is not "dirt." It is a plastic and malleable material composed primarily of molecules of aluminum silicates (Al2O3•2SiO2•2H2O). The ability to convert clay though heat to create hard, impervious pottery demonstrates that Native Americans had significant scientific expertise as physicists and chemists, in addition to their geological expertise in selecting rocks to create axes, sharp blades, and various types of points.

An eroding streambank may reveal a deposit of clay as much as several feet underneath the surface, and above the decaying bedrock whose minerals are realigning as clay particles as pressure/heat changes and water is incorporated. Creating pottery from clay requires separating out the organic material, rocks, and sand. Squeezing out the impurities can be accomplished by stomping and pressuring the clay with feet and hands.

In Virginia, all Native American pottery was created by first forming coils of clay. The coils were laid on top of each other in the desired pattern to form a bowl/cup/pot, then the edges were smoothed to create flat surfaces. Smoothing could be done with paddles as well as with the hands. Paddles could be scratched or covered with fibers in different patterns, creating distinctive types of pottery that can be identified today from just broken shards found in an archeological site.

In North America, the first pottery is known as the Stallings series. It was made around 2500 BCE in what is now the coastal area of South Carolina and Georgia. The first potters on what is now Stallings Island added plant fibers to their clay before placing a pot in the fire.

If heated or cooled too quickly, baked clay will break apart. The fibers served as the necessary "temper," reducing the risk of the clay cracking through expansion or shrinkage. Sand, shells, crushed rock, and even shards of previously-fired clay pots were used as temper to allow moisture to escape as clay was heated. Higher temperatures produce a more durable form of pottery. Clay that would crack at 300-400°F can, with temper in the mix, withstand heat as high as 1,200-1,500°F.

When a clay pot is heated, initially the water trapped between clay particles turns to steam. First pots were made from coils of clay, then air dried. Air drying was followed by slow heating in a fire. "Water smoking" drove off residual moisture, allowing the steam to escape harmlessly through pores between the clay particles. Whatever organic matter that was still in the clay burned; resulting carbon dioxide was emitted through the same pores as the steam.

Native Americans made only earthenware pots. Their open fires fueled by wood were not hot enough to produce watertight stoneware or porcelain, in which the clay molecules are tightly linked together. Early potters still managed to create earthenware pots that were watertight, capable of holding hot fluids such as soups and stews.

Creating watertight pots was accomplished by taking the slowly-heated, fully-dry pots out of the fire by using sticks to hold the hot clay. Green pine needles were placed into the pot, then the pot was put back into the fire with the open end facing down into the coals. Wood was placed around and above the pot, which was gradually heated until the clay glowed red.

Trapped inside the upside-down pot without much oxygen, the pine needles slowly roasted. The rosin in the needles vaporized and was deposited onto the clay, sealing any pores and making the inside of the pot watertight.

When heated to above 1022°F, at temperatures hotter than Native Americans could reach with wood fires, dehydroxylation occurs and stoneware can be produced. That process drives off the water molecules which were chemically combined with the aluminum silicate molecules. At slightly higher temperatures, the quartz molecules in the clay expand slightly, so the increase in heating must be slow.

Starting around 1200°F, clay particles are welded together and the impervious material is known as stoneware. If the original clay was sandy and too many quartz (silica) particles were included, however, the clay particles will not fuse tightly around all of the quartz grains and form a solid item. As the fired clay cools down, it will fall apart. The pottery maker will end up with just fragments of hardened clay instead of a useful pot. Even with careful production, perhaps 20% of the pots

Pure silica melts at 3,133°F (1,723°C). Quartz (SiO2) melts at a much lower temperature if various "fluxes" such as lime (CaO) or soda (NaO2) are added. When quartz molecules melt within the clay, the vitrified material produced is known as porcelain.

High temperature manufacturing required careful selection of clay and control over cooling. Clay particles and quartz (sand) crystals shrink differently when they cool. Quartz that melted in a hot furnace will recrystallize when pottery cools down to 1,064°F (573°C). The volume changes during "quartz inversion" as the position of the oxygen and silicon atoms and their covalent bonds realign. The quartz tetrahedron molecule changes shape during the transformation from beta-quartz to alpha-quartz. The clay matrix surrounding a grain of sand must cool slowly in an annealing oven, in order for the clay particles to realign around the quartz particles rather than crack apart.

Scholars once considered the possibility that the technology for producing pottery was brought to North America from northwestern Columbia. It is more likely that pottery was invented in North America, rather than brought by long-distance diffusion.

When the Stallings pots were first produced, potters at the Puerta Hormiga complex in Columbia used sand rather than fibers for their temper. Pottery "wares" associated with different cultures are distinguished by different techniques of manufacturing and also different styles of design.3

Diffusion of ceramics north to Virginia took a long time. In 2500 BCE, at the time the Stallings series emerged, Native Americans in Virginia were carving soapstone bowls. The stone containers could be used as soup poots in a fire, increasing the types of material (leaves, twigs, bones, skin) from which nutrients could be extracted. Natural outcrops in what are now Fairfax, Orange, Madison, Albemarle, Nelson, Amelia, and Brunswick counties provided the source material.

pottery replaced carved soapstone for containers, but stone and bone tools were still essential for other purposes such as clubs

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Grooved Stone Axe

Soapstone containers were an alternative to natural materials that could hold items, such as gourds and turtle shells. Bark and fiber could be woven to make a container, and animal skins could be shaped in many different sizes and styles. Unlike easy-to-manufacture utilitarian containers, scarce soapstone items must have had prestige value.

The oldest pottery in Virginia, found at sites in Albemarle and Caroline counties plus the White Oak Point shell midden on the Potomac River in Westmoreland County, are known as Bushnell Ware. Clay was tempered with fiber and crushed schist from the Piedmont, not with soapstone. Sites with Bushnell Ware have been dated to 1000 BCE.

Marcy Creek pottery was found in Arlington County at a site on Marcy Creek. It was tempered with crushed soapstone (steatite), which was readily available from nearby quarries. Marcy Creek pottery appears to be a close copy of earlier soapstone bowls, and that style of ceramics could be as old as 1200 BCE. Dating archeological sites is not an exact process.

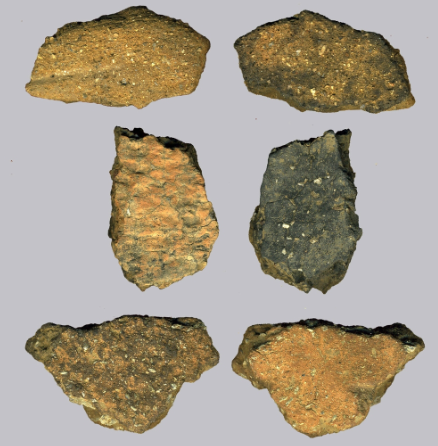

Marcey Creek ceramics, one of the first forms of pottery, was made with crushed soapstone (white flakes) to prevent pots from cracking when fired

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Marcey Creek Ceramic Sherds

Most early Virginia ceramics used items other than soapstone as a temper, and pottery was adopted last in areas near soapstone quarries. That suggests the need for clay pots was least where soapstone was readily available, that the trading networks to distribute soapstone containers were too limited to meet regional demand, and/or the people living near the outcrops were unable/unwilling to manufacture enough. Pottery enabled groups living on the Coastal Plain, far from soapstone but with easy access to clay, to make containers to meet their local needs.

Pottery could have been introduced to Virginia when a group moved north along the coastline, bringing the new technology with them. Alternatively, traders going south to what is now Georgia might have learned how to make pottery and brought new skills back to their northern homes. As noted by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, more than one approach was used:4

All Virginia pottery before the arrival of European colonists was manufactured without a pottery wheel. Lumps of clay could be pinched into a desired shape, to make small items. Larger vessels could be made by first creating coils of clay, then placing coils on top of each other to create a pot. The coils were pinched tight, and interior and exterior were smoothed. Burnishing tools to smooth the sides were made from stone, bone and wood. Sometimes wooden paddles were covered with a fiber fabric, and the impressions of the fabric were baked into the pot. Clarksville Ware shows where corncobs were used to mark the surface.5

impressions of cords are characteristic of Potomac Creek Ware

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Potomac Creek Ware

fabric was wrapped around some wet clay pots to decorate them, before firing

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Fabric Marked Ceramic Vessel

intentional markings of the exterior, perhaps with sticks, are visible on these examples of Clarksville Ware

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Clarksville Ware

Prehistoric residents in Virginia left no written records, and almost all organic materials have disappeared from natural decay. We can identify different cultures by examining the distinctive "wares," and even small broken pieces (sherds) provide key evidence needed to calculate which cultures can be associated to specific sites.

One style of pottery, Mockley Ware, was produced on the Coastal Plain from Delaware south to the James River between 200 to 900 CE. Crushed shells were used for temper. Shards excavated at archeological sites show impressions of cords and nets of fiber wrapped around a paddle. There was also a plain style with smooth surfaces. Discovery of Mockley Ware at sites near the Monocacy River may document expeditions into the Blue Ridge to quarry rhyolite from South Mountain/Catoctin Mountain. Valued stone was also traded among different cultural groups, but the excavated pottery shows that sometime over 1,000 years ago a group walked up the Potomac River Valley to obtain rhyolite directly from the source.6

crushed shells were used for temper in Mockley Ware

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), Mockley Ware

Archeologists try to identify changes in prehistoric settlement and subsistence patterns, as well as trading networks, by evaluating changes in pottery and points. The broken shards of pottery may - or may not - reflect the presence of people with different spiritual beliefs, alternative styles of tattoos and dress, distinct preferences for plants to gather and animals to hunt, and varying ways of cooking food. Only the pottery can be documented today, and inferences of cultural "complexes" and "phases" require critical thinking and making some assumptions to fill in the gaps.

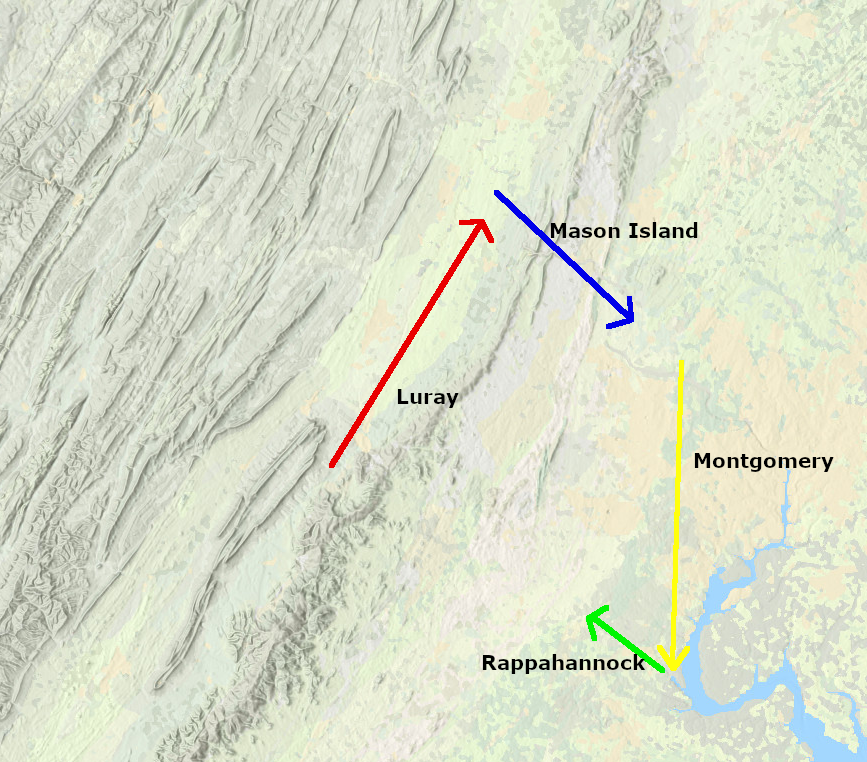

Three distinctive pottery wares, different styles of stone points and pipes, and different ways of burying the dead can be used trace the migration of several groups along the Potomac River in 1300-1400 CE (Common Era).

One group of people who around 1300 CE made shell-tempered Keyser Ware, a cord-marked pottery, are labeled today as people of the Luray Phase. They expanded their territory north, down the Shenandoah Valley, and occupied the upper Potomac River.

The land they occupied was not unsettled, it was not empty. That territorial expansion by the Luray Phase group displaced existing residents known as the Mason Island phase.

Changes in pottery excavated from Potomac River sites suggest that people of the Luray Phase displaced people of the Mason Island culture from their farmlands on the upper Potomac River and at the mouth of the Shenandoah River. Their Page Ware cord-marked pottery, made using crushed limestone as a temper, disappears from the archeological record at their old sites. In younger sediments the limestone-tempered Page Ware is replaced by shell-tempered Keyser Ware, made by the new Luray Phase residents.

Modern archeologists can recognize the time of migration by noting the changes in pottery styles (ceramic seriation). Changes in the shapes of stone "points," including arrowheads manufactured for hunting, survived in the soil while changes in language, forms of play, religion, and food preferences are harder to document.

crushed shells were used for temper in Mockley Ware

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), Page Ware

An abrupt change in pottery style indicates displacement of a group of people was quick and probably not voluntary. A mutual and voluntary association would be reflected in a gradual transition in style, with the limestone-tempered Page Cord-marked pots incorporating more and more characteristics of the later shell-tempered Keyser Cord-marked ware.

The forced-to-move Mason Island phase people migrated east of the Blue Ridge, following the Potomac River downstream through the gap at Harper's Ferry. In the Piedmont, the migrants encountered settlements of people that archeologists now associate with the Montgomery complex, identified in part by manufacture of Shephard Cord-marked ware with crushed granite or quartz as the temper.

It appears the Mason Island phase people forced most of the Montgomery complex villagers to move away, though excavations reveal that one group managed to stay on the upper Monocacy River until 1450 CE (Common Era). They were pushed downstream past the Fall Line to Piscataway Creek, the mouths of Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek, and later to the mouth of the Occoquan River. Their arrival is marked by the sudden appearance there of Potomac Creek Ware, both cord-marked and plain vessels.

The displaced Montgomery complex villagers continued to include crushed quartz in their pottery as temper, but at their new location crushed granite was no longer available. They adapted by using sand grains, in addition to crushed quartz, in what became a new Potomac Creek ware. The displaced Montgomery complex villagers also produced Moyaone ware, using both crushed quartz and sand grains for temper but making pottery with different designs and shapes.

The mouths of Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek were ecologically rich locations. Swamps filled with food for skilled hunters and gatherers were nearby. The soils were good for raising corn. Access to crabs, oysters, and fish was even better than upstream above the Fall Line, since Great Falls blocked the migration of anadromous fish. The Montgomery complex villagers must have been under sufficient pressure to move that they forcibly displaced existing residents who had taken advantage of the creek mouth locations.

We know the earlier residents, today called the Rappahannock complex, manufactured Townsend ware. It had a temper of crushed shells from mussels and oysters, with different decorative patterns than Potomac Creek ware. It disappeared from the mouths of Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek. When the new residents broke pottery, they left behind shards of Potomac Creek and Moyaone wares.

Rappahannock complex people who lived on the Coastal Plain at the mouths of Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek and made Townsend Ware (above) were displaced by migrants from the Piedmont who manufactured Potomac Ware

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), Townsend Ware

The changes in pottery, discovered 700 years later, revealed a chain of migrations between 1300-1400 CE. A group who lived upstream of the mouth of the Shenandoah River, the Luray Phase complex, moved to the Potomac River. They forced the Mason Island group to move down the Potomac River, to the eastern side of the Blue Ridge. The Mason Island group forced the Montgomery complex villagers to move east, past the Fall Line to the mouths of Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek. The Montgomery complex villagers forced the Rappahannock complex group to move inland.7

changes in pottery indicated migrations and forced displacements of different groups in 1300-1400 CE

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

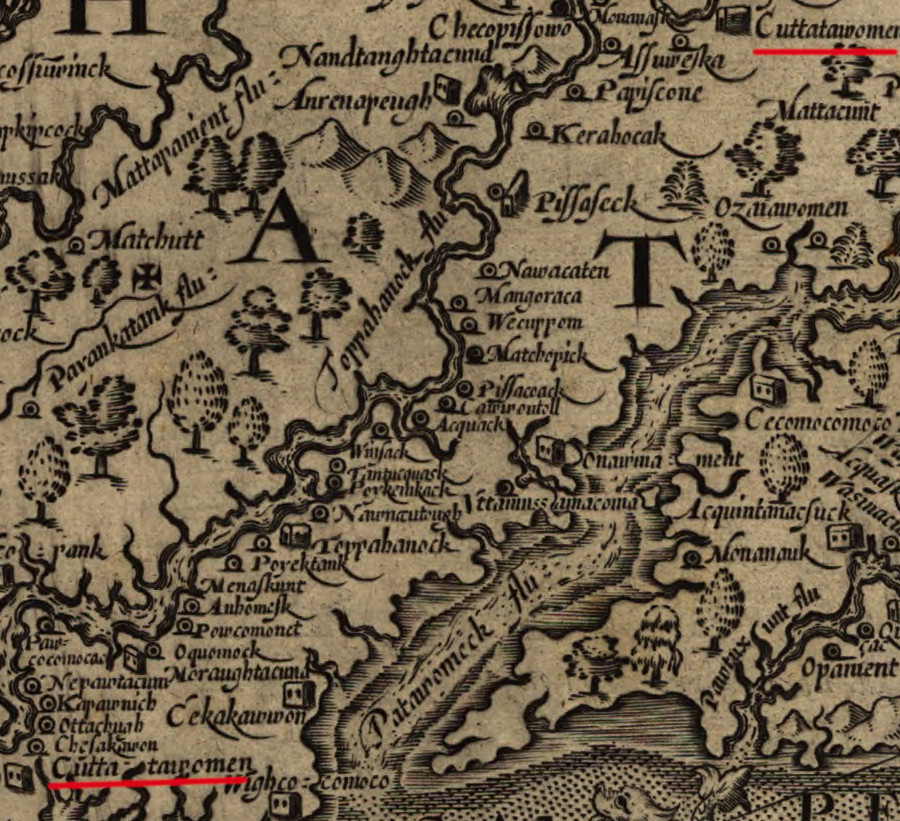

Another migration may be identified by a distinctive use of temper along the Rappahannock River. John Smith mapped two towns named Cuttatawomen, but place them 60 miles apart. Though his Algonquian language skills were still marginal and he may have misunderstood Native American place names when he explored that river in 1608, it is also possible that he was a very talented anthropologist who recognized the two places were related to each other.

Pottery makers near the mouth of the river typically used crushed shells as the temper to minimize cracking when pots were. Upstream pottery makers typically used crushed quartz as their temper - except at the upstream location also labeled Cuttatawomen site by Smith. Shell-tempered pottery has been found there by archeologists, suggesting either a permanent migration of coastal people or a site with spiritual significance visited regularly by people living at the mouth of the Rappahannock River.8

The upstrean location of Cuttawoman is probably the DeShazo archeologic site (44 Kg 3) in King George County. That site was mined for gravel to build Metrorail in the 1970's, and today is three lakes in the old gravel pits.

residents of Cuttatawomen near the mouth of the Rappahannock River may also have occupied the town of Cuttatawomen 60 miles upstream, based on the shell-tempered pottery found at both locations

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

the upstream site of Cuttatawomen in King George County was mined and transformed into water-filled gravel pits

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

National Park Service archeologists have excavated the earliest pottery enterprise of Virginia colonists in Yorktown

Source: National Park Service, NPS History Collection - Colonial National Historical Park