rainwater accumulates in inactive quarries, but operators pump out water in active quarries

Source: Virginia Geographic Information Network (VGIN), VBMP 2011 WGS Web Mercator (VGIN)

rainwater accumulates in inactive quarries, but operators pump out water in active quarries

Source: Virginia Geographic Information Network (VGIN), VBMP 2011 WGS Web Mercator (VGIN)

Quarries are open-pit mines. Sites where rocks are excavated and shaped to suit particular purposes, but not processed further to extract specific minerals, are typically called "quarries."

If the excavated material is smelted and/or chemically processed to extract just component minerals, such as gold and lead ore, then the hole in the ground is often called a "mine" rather than a quarry. Shallow holes, such as those created when iron ore was excavated prior to the Civil War, may be called "pits."

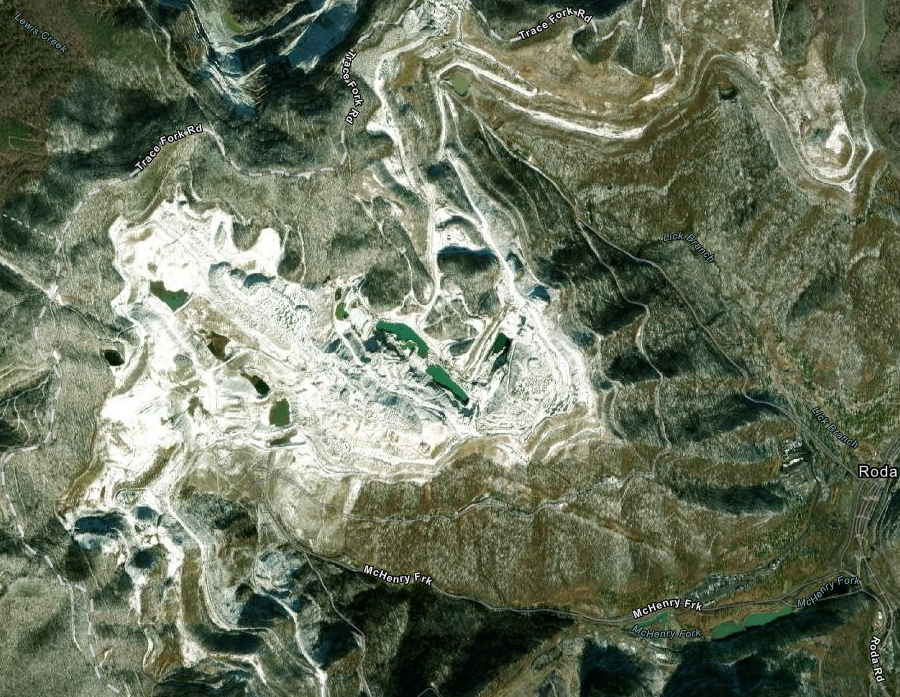

Some open-pit mines where rock is not smelted and/or chemically processed may still be called quarries. Sites where coal is excavated beneath the surface are called mines, even though processing of coal is limited to crushing and sorting - similar to production of gravel for construction projects - without any extraction of specific minerals within the coal. Open-pit coal mines are called "strip mines" rather than quarries. The surface layers of sandstone and shale are stripped away to expose coal seams, transforming local topography in a process known as mountaintop removal.1

sites for excavation of coal that reshape the topography of mountains in Southwest Virginia are described as strip mines, not as quarries

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In addition, grains of ilmenite, rutile, and zircon have been sorted from grains of quartz sand in the Old Hickory Heavy Mineral Sand Deposit in Dinwiddie, Greensville, and Sussex counties. Those mining sites, where the valuable ad heavier minerals are separate from quartz sand by gravity spiral concentrators without chemicals or smelting, are known as "quarries" rather than "mines."2

The oldest quarries in Virginia were excavated by Paleo-Indians. The Thunderbird site near Front Royal was used for thousands of years, starting about 10,000 years BCE (Before Common Era). Bands of people visited the quarry throughout the Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods. Excavation of rock probably continued past 1,000 BCE, the start of the Woodland period.

The valued resource extracted at the Flint Run Quarry, an archeological site designated 44WR4, was a cryptocrystalline form of quartz known as jasper. The physical characteristics of the very tiny silicon dioxide (SiO2) crystals allow the stone to be cracked into sharp flakes, which Native Americans shaped by percussion and pressure into points, knives, scrapers, and other tools.3

Jasper was also extracted from the Brook Run quarry (site 44CU122) in what is now Culpeper County. The quarry site was a narrow outcrop in the Culpeper Basin, which is primarily Triassic Period sandstone. As Pangea split apart, magma rose up to form dikes of basalt and fluidized quartz was squeezed into a crack in the sandstone. The quartz cooled to create a thin slice of jasper, surrounded by sedimentary sandstone.

The sandstone could not be shaped to create sharp edges useful in tools, but jasper is a cryptocrystalline form of quartz that produces sharp edges when broken. Sharp edges were essential for making spear points to hunt game animals, and for making knives to cut hides and meat.

Perhaps 11,000 years ago, Native Americans excavated into the rare crack in the Triassic Basin that was filled with jasper. To extract the jasper, they created a hole 3 feet wide and about 12 feet deep.

the crack in the sandstone, filled with jasper, was excavated by the first geologists in Virginia down to 12 feet below ground level

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Discovering the First Virginians

The site on modern Route 3 is one of the two oldest known quarries in Virginia, akong with the Tunderbird site on the Shenandoah River.. It became too difficult to crack loose pieces of jasper at the Brook Run deposit, perhaps because children had to be suspended upside down by their feet to stretch 12' deep to the bottom and swing hammerstones. The site was unknown until 1998, when archeologists discovered the quarry while surveying the route of a planned expansion of Route 3.4

the narrow character of the jasper deposit was exposed by archeologists in 1998

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Discovering the First Virginians

In the Culpeper Basin near the Potomac River, the earliest quarries were at outcrops of soapstone (steatite). About 4,500 years ago (BP, Before Present), Native Americans carved into exposed beds of soapstone and manufactured bowls and containers. Excavations at depth were not required to obtain enough stone to meet demand, or the capacity of the Native American stone carvers in the Archaic Period to produce useful objects.

The prehistoric soapstone quarry sites were abandoned as production of clay pots replaced manufacture of bowls from soapstone. In the 1800's and 1900's, quarries in Albemarle and Nelson County produced soapstone for building material. The Nelson & Albemarle Railway was constructed to carry the quarried material to market, and to processing facilities located away from the quarries. A popular television show, "The Waltons," was based on the community of Schuyler, which developed around the quarries of the Virginia Alberene Company.5

Colonists began to quarry sandstone from deposits in Triassic Basins in the 1700's. Plantation mansions made from iron-rich red sandstone blocks demonstrated even greater wealth and power than brick houses. Buildings were even more impressive when edged with white blocks of Aquia Sandstone. The large Aquia Sandstone quarry on Government Island, source of sandstone used to build the President's House (now the White House) and US Capitol, is today a Stafford County Park. The outcrop at Freestone Point is now part of Leesylvania State Park.

At Manassas National Battlefield Park, the famous Stone Bridge and Stone House were built from locally-excavated sandstone. Dinosaur tracks have been found in sandstone quarries, and are visible in slabs used for the patio at the Oak Hill home of President Jams Monroe.

in the 1700's, mansion houses made with white Aquia Sandstone trim around red Triassc Basin sandstone created an impression of wealth and power

Source: Virginia Department of Historical Resources (DHR), 079-0013 Mount Airy

Almost all modern quarries in the Culpeper Basin are located at dikes and sills of hard igneous basalt which intruded into softer sandstone sediments. The basalt is crushed excavated and crushed to make gravel for road and building construction. One quarry in Northern Virginia, on the Occoquan River near Lorton, excavates granite. Granite quarries are concentrated along the Fall Line, where plutons were emplaced 330 million years ago as the Iapetus Ocean was closing.6

Source: Friends of Mineralogy Virginia Chapter, Northern Virginia Trap Rock Quarries

Elsewhere on the Piedmont, slate from Buckingham County is sliced to create roofing materials.

granite which solidified 330 million years ago is extracted and crushed at the Boscobel quarry in Goochland County

Source: Google Maps

In the 1800's and 1900's, some limestone quarries were located east of the Blue Ridge. The bedrock and marl deposits of calcium carbonate were quarried and crushed primarily for agricultural lime. Some of the crushed lime was used for creating mortar for brick buildings. Thomas Jefferson used lime from the Everona Member of the True Blue Formation in Albemarle County to build Monticello and the University of Virginia.

Near the Nansemond River, marl was quarried from ancient coquina beds in the Yorktown Formation. The marl was crushed and used to make cement, as well as spread on farm fields to improve soil quality. The excavated pits are now part of Lone Star Lakes Park in the City of Suffolk.

marl quarries near the Nansemond River are now water-filled lakes in the City of Suffolk

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In Loudoun County, limestone was excavated and "burned" in lime kilns to make cement. In addition, a limestone conglomerate known as Calico Rock or Potomac Marble was quarried from the Leesburg Member of the Balls Bluff Siltstone in Loudoun County. It was used for Statuary Hall columns in the US Capital.7

in many places, Calico Rock is not suitable for building stone

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Photogallery - Digital Geologic Map and Database of the Frederick 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia (2002)

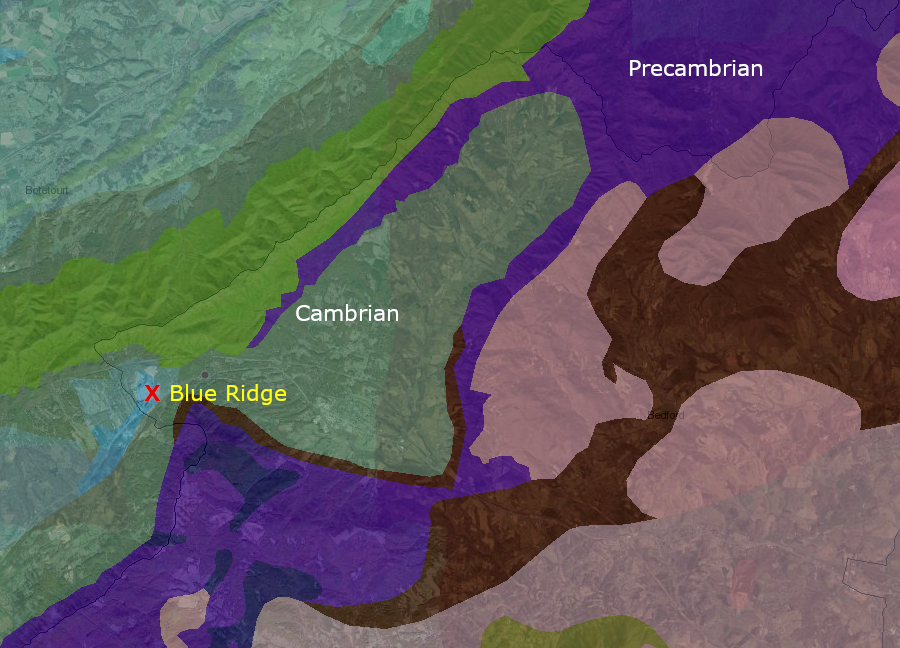

Most modern limestone quarries are in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, with the exception of "windows" or "fensters" in the Blue Ridge physiographic province and in the James River lron and Marble Belt (such as Rockydale Quarry in Appomattox). Northeast of Roanoke, thrust faulting placed Precambrian metamorphic rock overtop of Cambrian limestone sediments, but the older overburden has eroded away and exposed the younger bedrock underneath. At the Blue Ridge Quarry, dolomite (magnesium-rich limestone) is excavated from the Conococheague Formation.8

at Blue Ridge Quarry, dolomite is excavated from a "window" within the Blue Ridge physiographic province

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME), interactive map of Virginia's geology and natural resources and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Most limestone is processed at quarries for aggregate and agricultural lime used to alter the pH of soil to increase productivity, but some is carved into blocks of desired shape for dimension stone.

Elkton Quarry in Rockingham County produces agricultural lime from sediments that accumulated at the bottom of the Iapetus Ocean

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The exterior of buildings at Virginia Tech use limestone with different shades of grey, brown and black, creating a distinctive Hokie Stone appearance. About 80% of Hokie Stone comes from a quarry owned by Virginia Tech, and the remaining 20% is purchased from a nearby quarry to ensure the right mix of colors will be available.9

Hokie Stone must be quarried and cut to desired dimensions, before being placed on buildings at Virginia Tech

Source: Virginia Tech, VT Stories: A Legacy of Hokie Stone

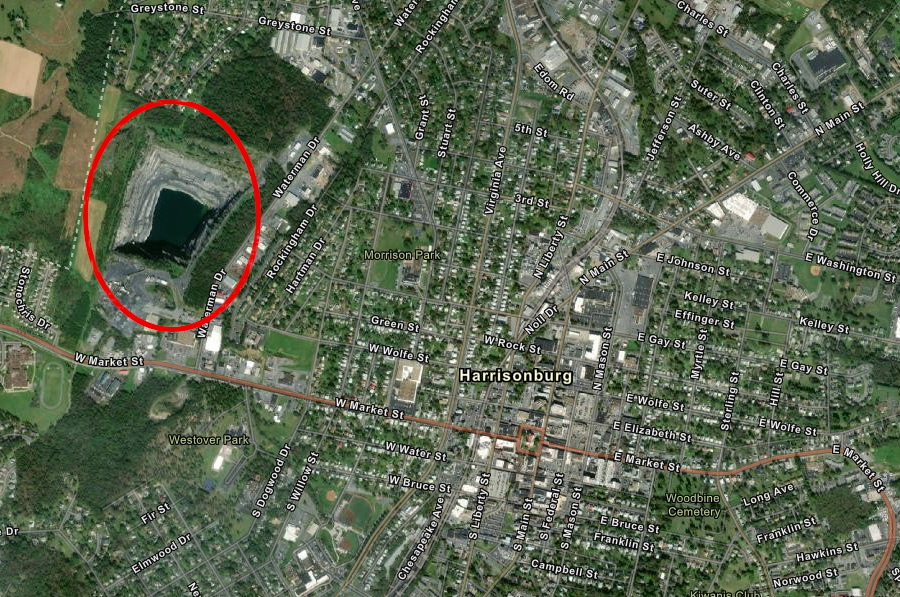

Buildings at James Madison University in Harrisonburg are made from a monochromatic dark blue-grey color, giving them a different character. The bluestone used at James Madison University comes from the Frazier Quarry.10

Frazier Quarry, source of the bluestone used at James Madison University, is located within the city limits of Harrisonburg

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

On the Coastal Plain, the soft sediments cover the hard metamorphic basement rock and granitic plutons. Most quarries produce sand and gravel for construction. It is sorted by grain size, but does not need to be crushed or processed further. West of I-95 near the North Carolina border, shallow pits were excavated to process the sediments at the Old Hickory Heavy Mineral Sand Deposit and extract grains rich in titanium.11

titanium was extracted from shallow pits excavated in the Old Hickory Heavy Mineral Sand Deposit

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

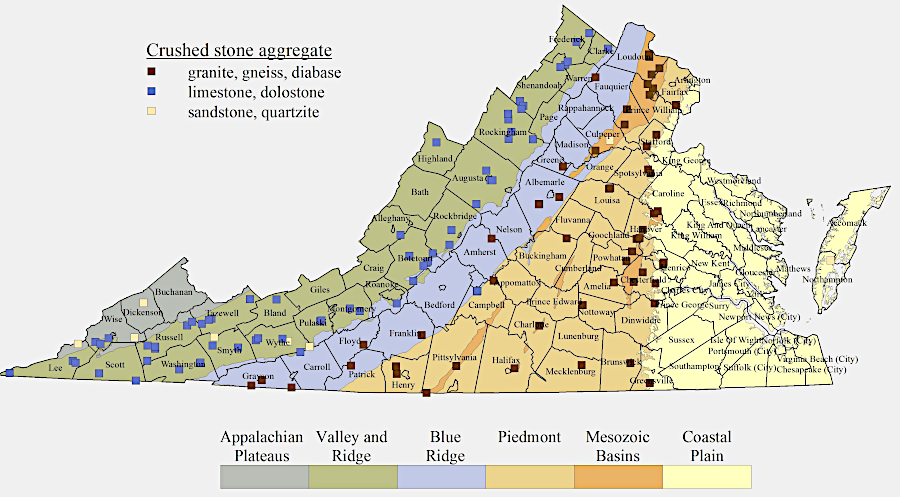

In 2019, the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy identified 137 "mines producing crushed stone in Virginia." The quarries were located in 60 of the state's 95 counties. Most rock was crushed at quarries to create gravel in various sizes needed for road and building construction, including aggregate in concrete. Large boulders were used for landscaping, protective barriers to block vehicles, and for protecting shorelines.12

there are quarries producing crushed stone in 60 of Virginia's 95 counties

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Crushed Stone

the Puddledock Sand and Gravel quarry along the Appomattox River can sell material for local use near Petersburg, and barge it to Hampton Roads and Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

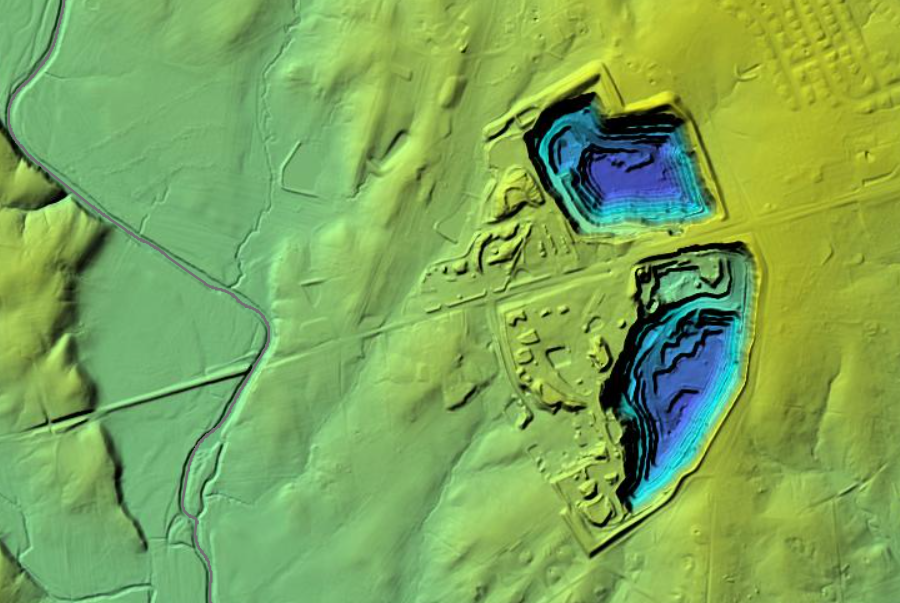

LIDAR reveals the excavation of basalt quarries in Fairfax County, just east of Stone Bridge over Bull Run

Source: Fairfax County, LiDAR Digital Surface Model -2018 and LiDAR Elevation Viewer

dark gray basalt gravel used for a road has a distinctly different color from the underlying bedrock at Fraser Preserve in northern Fairfax County