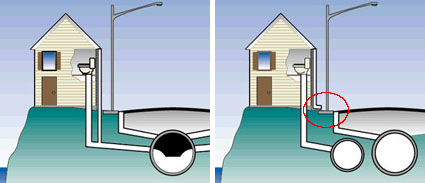

Lynchburg has focused on separating the combined sanitary sewer/stormwater pipes (left), so wastewater and drainage from roof gutters will stay in separate pipes (right)

Source: City of Lynchburg, About CSO

Lynchburg has focused on separating the combined sanitary sewer/stormwater pipes (left), so wastewater and drainage from roof gutters will stay in separate pipes (right)

Source: City of Lynchburg, About CSO

Lynchburg was one of the first cities in Virginia to build a drinking water system. Once fresh water arrived in volume at houses, the city needed a sewer system to dispose of wastewater. Lynchburg constructed an underground set of pipes carrying wastewater and stormwater, together, directly to the James River. Those pipes dumped raw sewage directly into the river every day and, after a rainstorm, the pipes carried stormwater to the James River as well.

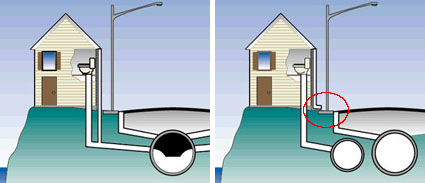

In 1955, Lynchburg built its first wastewater treatment plant to treat the sewage and reduce pollution impacts on the river. To move sewage to that new facility, the city built an interceptor pipe parallel to the James River. The interceptor connected the pre-existing sewer pipes in 21 watersheds (8,300 acres) to the new treatment plant. As described by the city:1

Lynchburg built its waste water treatment plant downstream of the city in 1955

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

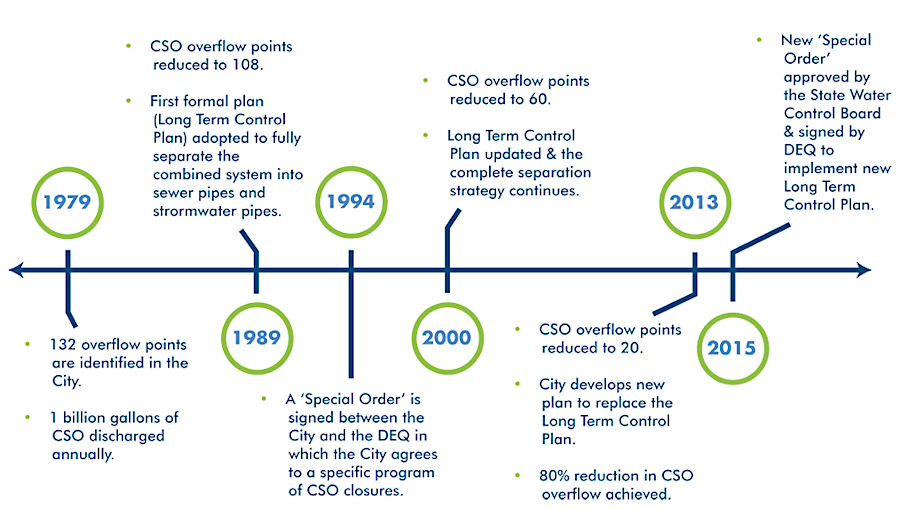

Lynchburg ended up with 132 overflow outfalls that could relieve pressure on the pipes by releasing combined wastewater/stormwater into the James River, or tributaries flowing into the James. Dumping untreated sewage protected the pipes, but not local streams. To meet the requirements of the Clean Water Act as amended in 1972, the city needed to stop intermittent dumping of raw sewage into the river.2

In 1994, Lynchburg committed to a Long Term Control Plan and agreed to spend $350 million over 20 years to gradually separate its stormwater and sanitary sewer systems. A key step in the plan was to disconnect downspouts on 4,000 houses/businesses that directed stormwater into the same pipes carrying sewage, increasing the flow to the city's wastewater treatment plant by 20%.

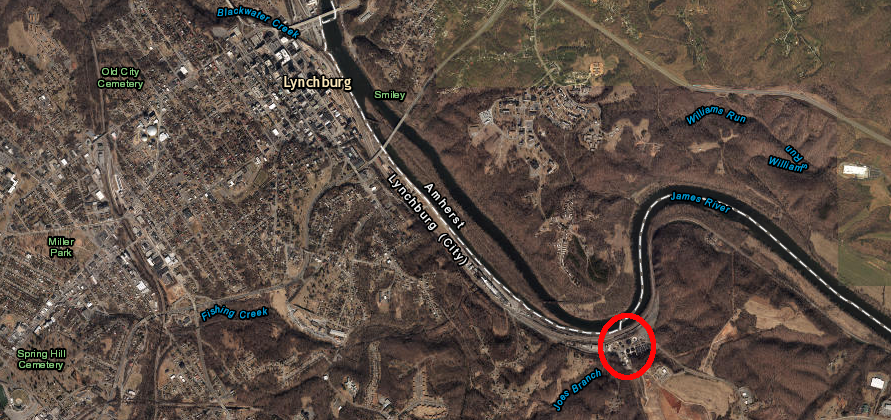

The most expensive single investment was installation of seven miles of new interceptor pipe along the James River, costing $60 million. Some of the "arteries of the sewer system" were as wide as seven feet. People who use the city's sewer system (ratepayers to the utility) were obliged to fund the construction required to separate the now-combined systems, but the city was successful in obtaining state and Federal grants to reduce substantially the costs imposed on local ratepayers.

The city negotiated an agreement with the State Water Control Board and EPA that rate increases would be based on a defined percentage (roughly 1.25%) of median household income in the city. That limit on revenue, combined with a decision by regulatory agencies to allow the completion date to be based on the available funding rather than an arbitrary timeline, ensured that ratepayers in Lynchburg would not be hit with exorbitant increases in their sewer fees. EPA later required that other jurisdictions accept rate increases up to 2% of median income.3

new stormwater sewer lines (red), to separate stormwater from existing sanitary sewer system (green) in Lynchburg

Source: City of Lynchburg project maps

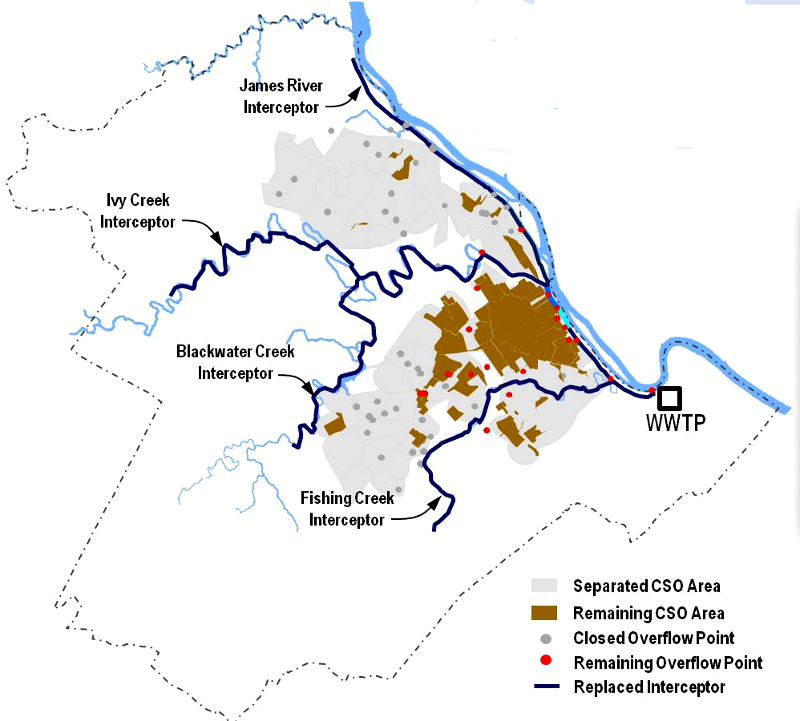

By 2012, Lynchburg had eliminated all but 20 of its 132 overflow outfalls, reduced the volume of Combined Sewer Overflow discharges by 80%, and completed 60% of 59 priority projects. The city saved the most expensive projects for last, and then examined "lessons learned" in other communities to change its plans.

Lynchburg began to revise its strategy in 2012, when faced with the impacts of massive disruption and very high costs to tear up streets and install separate stormwater/sanitary sewer pipes in the 4-square mile historic downtown core. It stopped planning to separate all remaining stormwater and wastewater pipes.

In the 2015 Long Term Control Plan, Lynchburg chose to retain the combined pipes already in the ground rather than continue to install a second system of stormwater-only pipes. The new approach was to treat the combined water, by transport the combined sanitary waste/stormwater from the downtown district to an expanded the wastewater treatment plant. That decision meant the new interceptor pipe along the James River would occasionally deliver high volumes from the remaining Combined Sewer Overflow area.

The city determined that it was more cost-effective and less disruptive to meet Clean Water Act requirements by upgrading the wastewater treatment plant to process those high flows, than to install separate pipes in the historic city core. Costs to close two more overflow outfalls (CSO 61 and CSO 125) and to expand the wastewater plant to process the remaining combined flows were estimated to be $60 million. Continuing the original approach, separating all pipes to close the remaining 20 overflow outfalls, was expected to cost $280 million.

One tradeoff: the State Water Control Board and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had to accept that some overflows with some untreated sewage would occur in the future from the 17 remaining overflow outfalls. Six discharged directly into the James River, while 11 others discharged into nearby streams. Only one of the 11 was predicted to overflow more than once per year.4

Eliminating the combined sewers would not completely eliminate the potential for sewage spills into the James River. After a massive storm known as a "derecho" in July, 2012, the Lynchburg wastewater treatment plant lost electricity and released 2.6 million gallons of partially-treated sewage. The facility lacked backup generators and Lynchburg had not planned for a region-wide event where multiple sources of electricity would fail.5

in 2012, after Lynchburg had eliminated discharge from 67% of the CSO Area, the city changed its pollution control strategy in order to save money and avoid disrupting downtown

Source: American Academy of Environmental Engineers and Scientists, Holistic CSO Long-Term Control Plan Update

In 2020, the General Assembly passed legislation requiring Lynchburg to plan to eliminate the remaining discharge of untreated waste. The legislature required Lynchburg to create an interim plan by 2022, a final plan by 2024, and to complete construction of projects in the interim plan between 2022-2027. In 2021, after spending $300 million on many projects, 17 of the 132 overflow outfalls remained to be closed.

As the US Congress considered passing legislation in 2021 to provide a massive increase in funding for infrastructure, Lynchburg officials proposed budgeting $25 million to obtain a matching $25 million. After spending $300 million over the last three decades, the city calculated that 95% of the Combined Sewer Overflow discharges could be eliminated by spending $50 million more over five years. That would exceed the requirements of the Environmental Protection Agency to capture 85% of the overflows, and speed up completion of the project by 10-15 years.

Governor Northam's budget, passed by the General Assembly, matched the city's request. In contrast, he provided only $50 million for Richmond and another $50 million for Alexandria to fund improvements to their Combined Sewer Overflow systems. Richmond had requested $883 million, and Alexandria had requested $500 million.6

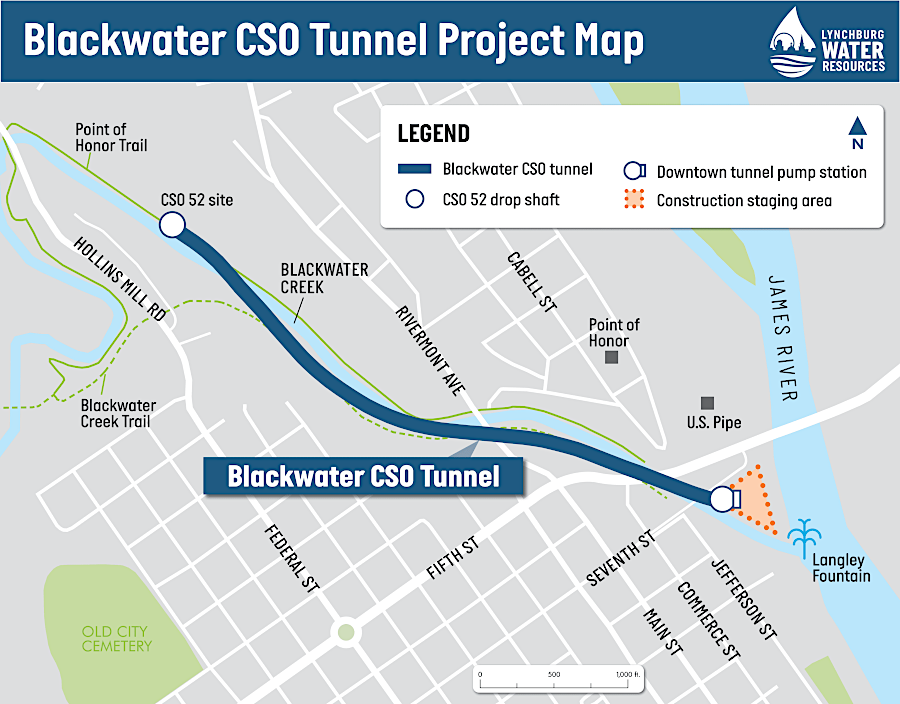

Building the $105 million Blackwater CSO Tunnel was the city's largest infrastructure project in history, and nearly all of the work was done out of sight over 70' underground. The 2015 2015 Long Term Control Plan determined that when the James River Interceptor tunnel filled up, the overflow was to be diverted into the Blackwater CSO Tunnel. The tunnel was expensive, but the alternative of disconnecting all remaining connections of the stormwater and wastewater pipes was more expensive.

The Blackwater CSO Tunnel is a 12-foot diameter pipe that extends for a mile underneath Blackwater Creek down to the confluence with the James River. The pipe was sized to hold 4.7 million gallons of sewage and storm water. The tunnel was designed to fill up during a storm, then afterwards the stored wastewater/stormwater would be pumped to the city's wastewater treatment plant.

the Blackwater CSO Tunnel extends for a mile underneath Blackwater Creek

Source: City of Lynchburg, Construction of the Blackwater CSO Tunnel Has Begun!

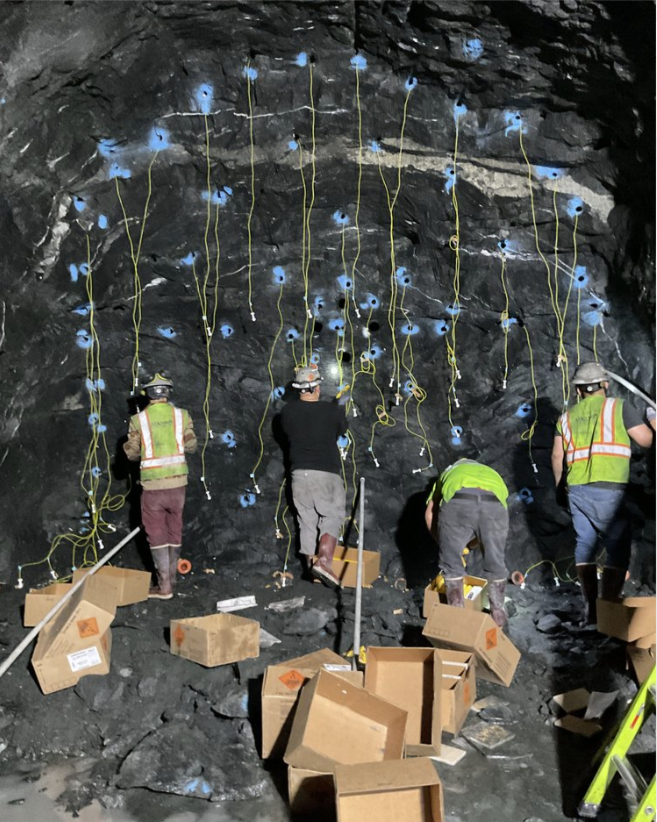

The construction manager for the project described the excavation process, starting with a vertical shaft before drilling horizontally for a mile:7

preparing to blast in the Blackwater CSO Tunnel

Source: LYHBeyond, Photoes

When construction of the Blackwater CSO Tunnel started in 2024, the city had already reduced the number of Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) discharge points from 132 to 17 and cut the volume of overflows by 93%. When completed in 2027, the new tunnel would reduce the number of overflow events each year from six to two, and cut the volume an additional 5%.

An outlet channel at the end of the tunnel was included in the project, in order to allow for discharge of combined sewage and stormwater if a rain event exceeded the storage capacity of the tunnel.8

Lynchburg started work on intercepting its Combined Sewer Overflow discharges in 1979

Source: City of Lynchburg, CSO History

Source: City of Lynchburg, The Blackwater CSO Tunnel: How it will work

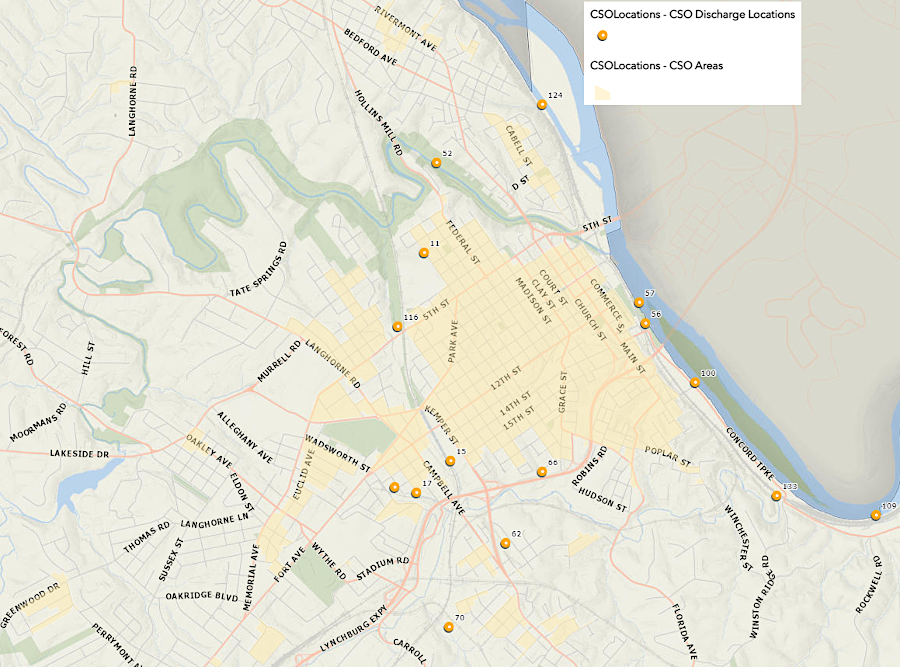

in 2021, six Combined Sewer Overflow outfalls were still discharging untreated waste into the James River

Source: City of Lynchburg, CSO Locations