Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Locations in Virginia

sanitary sewers carry waste to treatment plants in pipes that are completely separate from the stormwater system, except in three Virginia cities

Source: City of Alexandria, Proposed Long Term Control Plan Update Summary for the Combined Sewer System

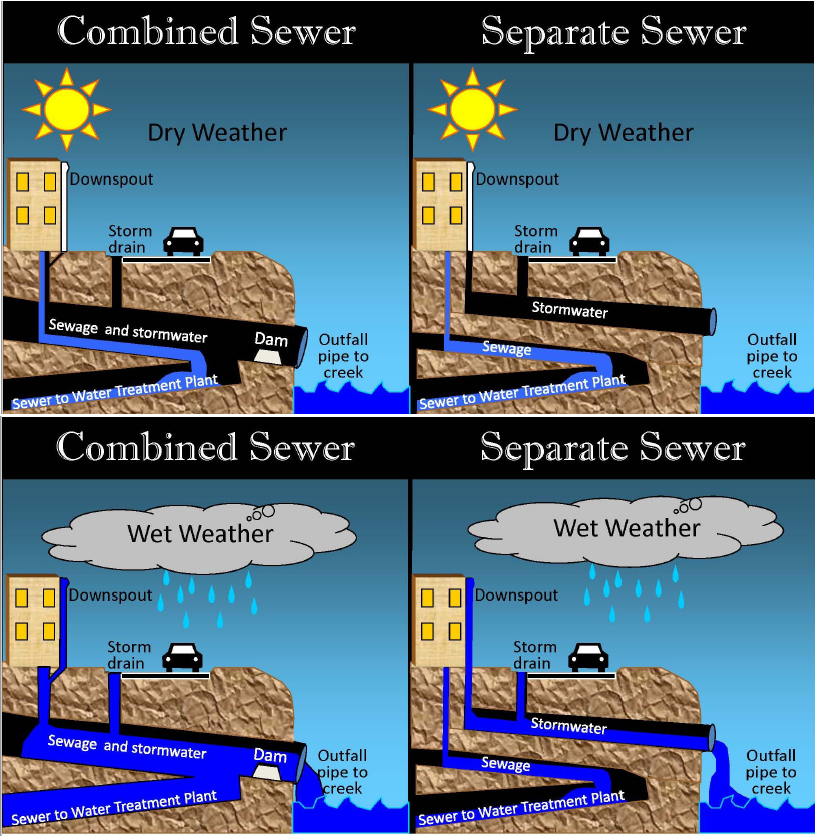

In most Virginia communities, one set of underground sewer pipes carries wastewater away from homes and businesses to wastewater treatment plants (WWTP's). Sewage flushed from houses will flow and be pumped through those pipes to WWTP's, where it is processed to remove solids and kill bacteria. In the Chesapeake Bay watershed, additional processing removes most nitrogen and phosphorous as well, minimizing the nutrients in wastewater that over-fertilize the Chesapeake Bay.

Normally a separate set of ditches/pipes carries stormwater runoff to Virginia's streams. Except in three Virginia cities today, the stormwater disposal system is independent from the wastewater infrastructure.

Wastewater is treated to meet Clean Water Act standards before being discharged back into a creek or river. In contrast, stormwater is not treated to remove bacteria or nutrients. Pollution that washes off roads and lawns will flow through the stormwater ditches and pipes, directly into Virginia's waterways streams. Most of whatever was in that stormwater at the start of its journey will reach the Chesapeake Bay, Atlantic Ocean, or Gulf of Mexico.

Animal waste from dogs, cats, deer, raccoons, geese, etc. washes into streams via stormwater, in addition to the nitrogen, phosphorous, and sediment that affect Chesapeake Bay water quality. Many of the streams and lakes on Virginia's Section 303(d) List of Impaired Waters are polluted by excessive levels of bacteria. Impaired streams, such as Hunting Creek at Alexandria, are not safe for primary recreation use such as swimming.

When Virginia's urban areas first developed, underground pipes carried sewage to nearby streams. Much later, starting in the 1930's, wastewater treatment plants were built at the end of those pipes to process the sewage before discharging it into the streams.

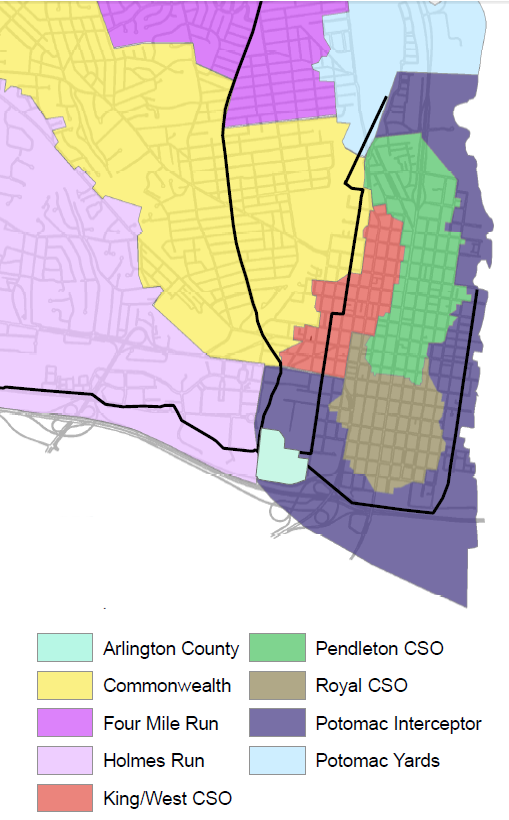

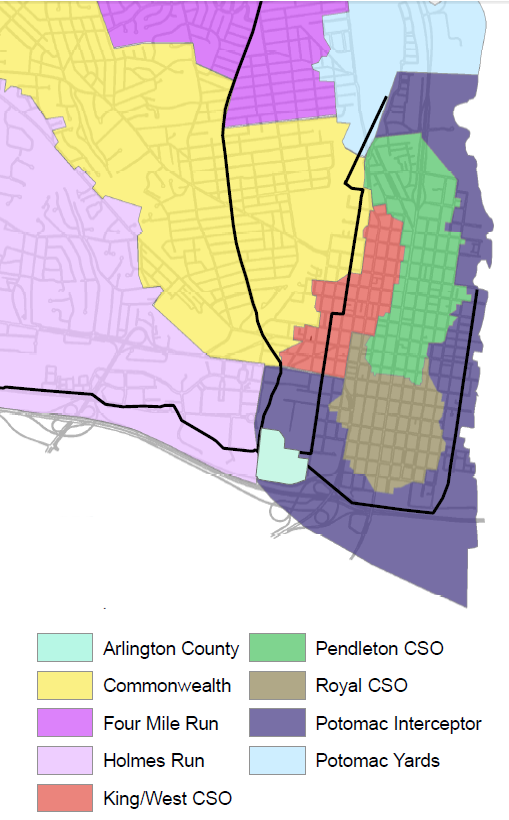

Sanitary Sewersheds in Alexandria

Source: City of Alexandria, Sanitary Sewer Master Plan

In some densely-developed areas, including Alexandria, Ashland, Bristol, Cape Charles, Colonial Heights, Covington, Fredericksburg, Lynchburg, Newport News, Radford, Richmond, Roanoke, and Waynesboro, pipes for carrying stormwater to the nearest stream were connected to the wastewater pipes.

When stormwater systems were first developed in those communities, downspouts from gutters on houses in old neighborhoods or from buildings downtown were connected to the sewers. In addition, some inlets from gutters carrying water off streets in urban areas were also connected to pre-existing sewer pipes.1

Combining the two systems for disposing of sewage and stormwater simplified the construction process. Just one set of pipes was placed underground, saving money and minimizing disruption from digging up streets to install a second set of pipes. Combining waste and stormwater flows also ensured a complete flushing of the sewer system during storms, but complicated the challenge of meeting water quality standards.

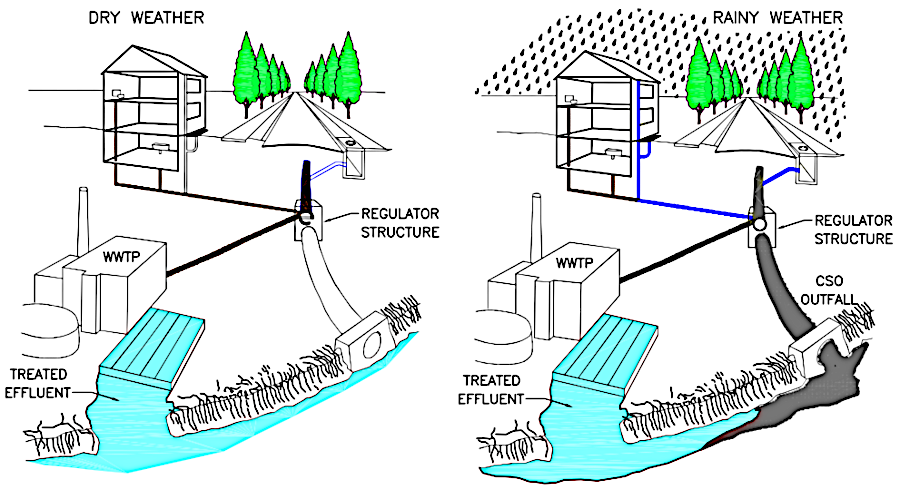

In some urbanized areas, outlet gates were incorporated in the underground piping system to dump excessive storm flow directly into streams and rivers. The mixture of sewage and stormwater is not treated before exiting the pipes. Solid chunks of human waste/toilet paper might be seen floating downstream from the discharge gates, and people downstream complain that the mix is foul-smelling.

By 1990, the stormwater system had been separated from the sanitary sewer system in all Virginia communities except four. Covington eliminated Combined Sewer Overflows in the 1990's. At the start of the 21st Century, only Alexandria, Richmond, and Lynchburg still had a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) infrastructure.2

Those three cities dumped raw sewage into the Potomac River (Alexandria) or James River (Lynchburg and Richmond) during rainstorms, when the surge of stormwater/sewage exceeds the volume of the pipes or capacity of the wastewater treatment plant to process the peak inflow.

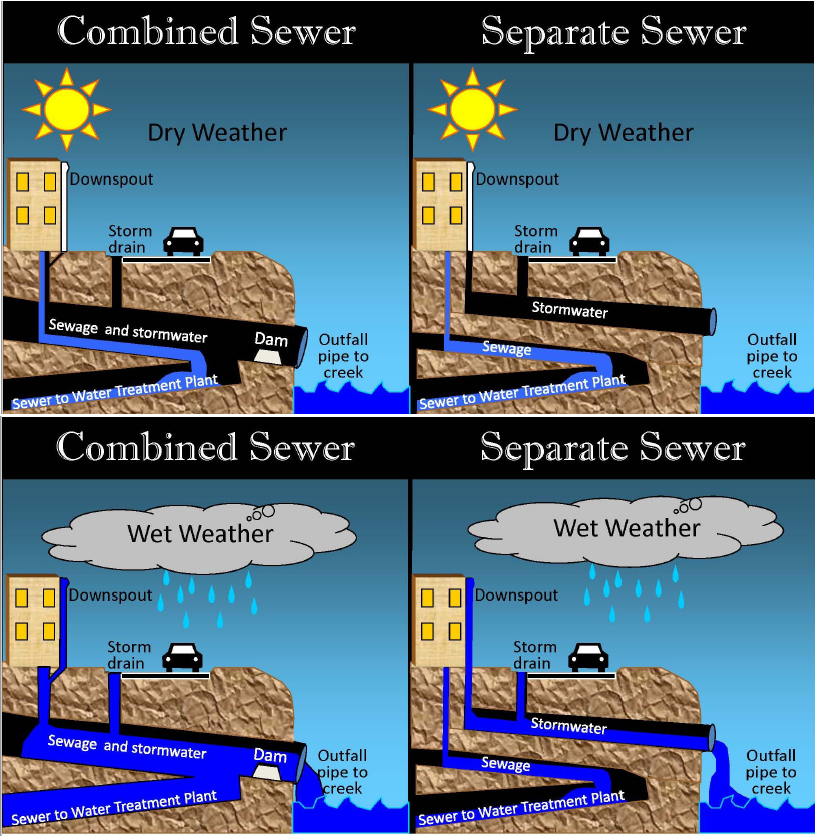

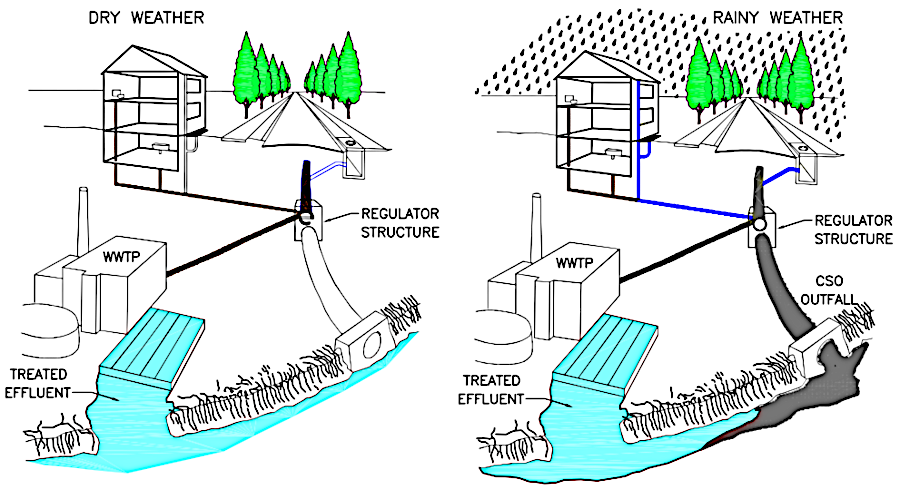

flow in Combined Sewer Overflow systems will go to wastewater treatment plants in dry weather, but be discharged at outfalls in wet weather

Source: City of Alexandria, Proposed Combined Sewer System Permit Information Meeting & Public Hearing (August 5, 2013)

Since passage of the Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency has issued national standards for treating effluents to acceptable levels of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), total suspended solids (TSS), fecal coliform, pH, and oil/grease. Wastewater plants in the Chesapeake Bay watershed must also remove nitrogen and phosphorous. Those two nutrients stimulate excessive algae growth, and when that algae decays it creates dead zones in the bay.

Wastewater treatment plants have been upgraded since the 1980's to meet the Clean Water Act and Chesapeake Bay standards. Building extra treatment capacity is very expensive, so the size of those wastewater plants is based on the projected flow of sewage from houses and businesses. When it rains in an area with a sewer system, rainwater replaces air in the gaps between soil particles around the pipes. That increase the pressure, and rainwater seeps into the pipes. Infiltration and Inflow (I&I) of stormwater increases the overall volume flowing into the wastewater treatment plant.

Wastewater plants have three options when the inflow exceeds the treatment capacity.

1) Flow can be pushed through the wastewater plant so fast that treatment would be incomplete before final discharge. Discharging partially-treated sewage would violate Clean Water Act standards. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) would eventually order expansion of treatment capacity, a very expensive action that would require an increase in the sewer service fees charged to homeowners and businesses.

2) Some wastewater plants have built temporary storage ponds. During and immediately after storms, excessive flow is diverted to those storage ponds. It could take days or weeks to drain those ponds slowly and treat the effluent, while neighbors complained that the mix of stormwater and sewage was foul-smelling.

3) Outlet gates in the Combined Sewer Overflow system in Alexandria, Richmond, and Lynchburg can be opened, pouring untreated human waste and stormwater directly into the Potomac or James rivers.

Across Virginia, except for those three downtown areas, sanitary sewer systems are separate from stormwater management infrastructure. Where stormwater is steered to the stream channels through a separate set of ditches on the surface and separate underground pipes, underground pipes for wastewater are large enough to handle the volume of water generated by toilets/showers/kitchens but are not sized to handle surges of stormwater generated by rainstorms.

the three cities with CSO's in Virginia are all in the Chesapeake Bay watershed

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Virginia Watersheds

Dumping raw human waste mixed with stormwater into Virginia's waterways is a pollution event. Those events are planned, intentional, and expected; they are not accidents. The Combined Sewer Overflow infrastructure pipes were designed to have outlets (overflow outfalls) where combined stormwater/sanitary waste would be discharged directly to streams, once capacity of the wastewater treatment plant to store more liquid or process its maximum volume was reached.

In storm events, the additional freshwater from rainfall was expected to dilute the polluted runoff, and the mix of extra runoff/sewage was expected to be an acceptable practice. After all, consolidated systems were built long before most wastewater treatment plants. Even when sanitary and stormwater pipes were separate, the sanitary pipes discharged raw sewage directly to streams.

What changed in the 1950's, after construction of the combined sewer systems, was the public's willingness to accept water pollution. By the 1960's, it was clear that the public would no longer concur with the old adage that "dilution is the solution to pollution." By the 1970's, the Clean Water Act required cities with existing Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) systems to reduce discharges of untreated waste. Since the 1980's, rates charged to utility customers in Alexandria, Richmond, and Lynchburg have helped fund (along with state/Federal grants) some massive construction projects to divert stormwater and wastewater in order to reduce - but not eliminate - pollution.

Long ago the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recognized that substantial funding, over several decades, would be required to reduce pollution from existing Combined Sewer Overflow infrastructure. EPA started by requiring each community with a combined system to make progress and implement pollution reduction through a Long Term Control Plan (LTCP), with nine minimum controls on:3

- Proper operation and regular maintenance programs for the sewer system and the CSOs

- Maximum use of the collection system for storage

- Review and modification of pretreatment requirements to assure CSO impacts are minimized

- Maximization of flow to the publicly owned treatment works for treatment

- Prohibition of CSOs during dry weather

- Control of solid and floatable materials in CSOs

- Pollution prevention

- Public notification to ensure that the public receives adequate notification of CSO occurrences and CSO impacts

- Monitoring to effectively characterize CSO impacts and the efficacy of CSO controls

The environmental impacts of dumping diluted-but-untreated sewage into the Potomac and James rivers must be addressed. Alexandria, Richmond, and Lynchburg have not been grandfathered or exempted from meeting the requirements of the Clean Water Act.

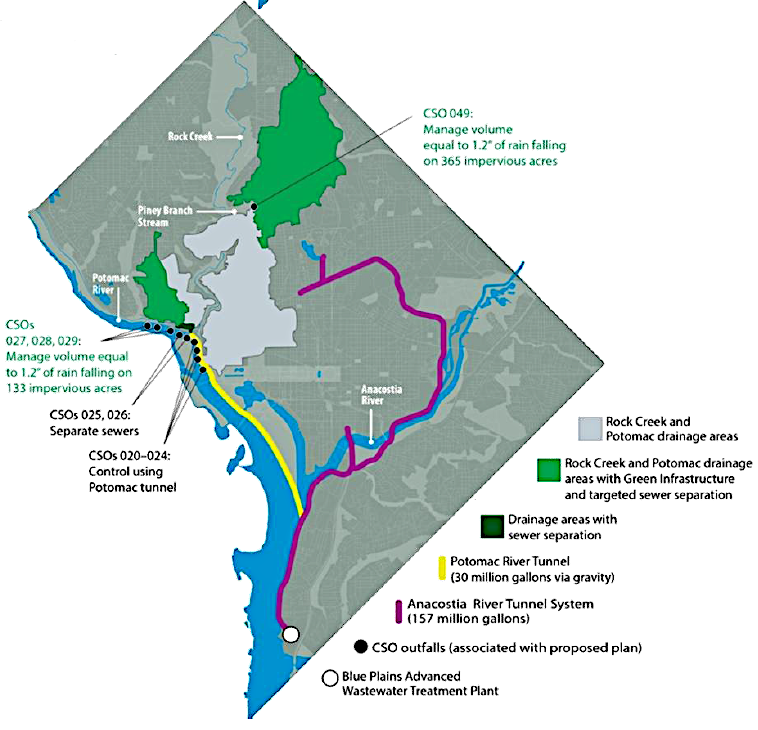

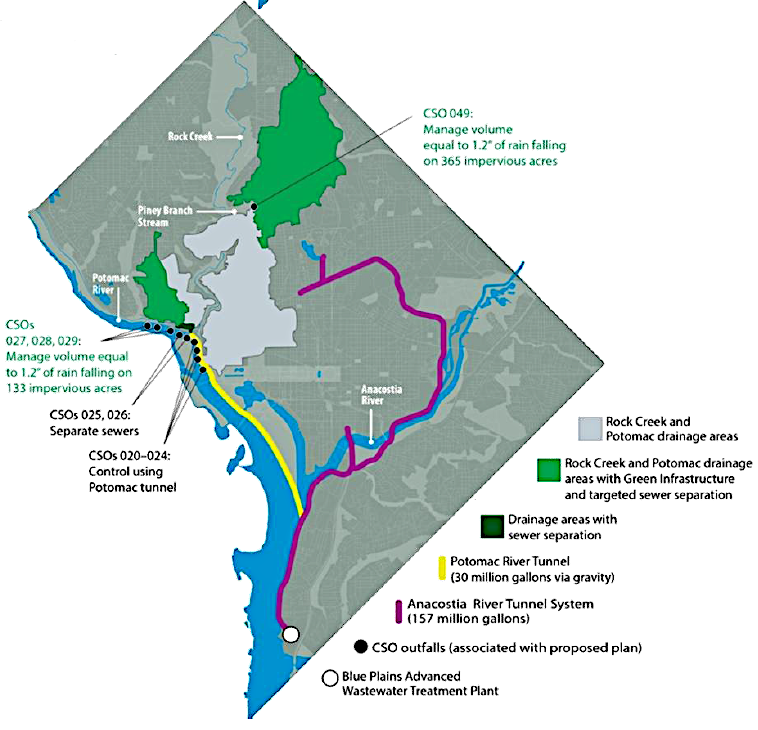

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has required each city to develop Long Term Control Plans that described how water quality standards would be met, so all waters in Virginia affected by the Clean Water Act would be "fishable" and "swimmable." The District of Columbia is also required to minimize the Combined Sewer Overflows from its sewer system, which directed raw sewage to the Anacostia and Potomac rivers until the Blue Plains treatment plant was completed in 1938. At the start of the 21st Century, the sewers overflowed 75 times a year and dumped 3 million gallons into the rivers.

The District's Clean Rivers Project is a three-decade effort, scheduled for completion in 2030. It includes a series of tunnels dug by Tunnel Boring Machines through the bedrock at a depth of 100 feet, below all other underground infrastructure such a Metrorail tracks. The tunnels intercept combined stormwater/sewage, store the peak flows, then transport the liquid to the Blue Plain facility when it has capacity to process the waste.4

the District of Columbia is building tunnels and green infrastructure to treat rainwater and minimize untreated sewage flows into the Potomac and Anacostia rivers

Source: District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (WASA), Long Term Control Plan Modification for Green Infrastructure (p.ES-4)

Even modern sewer systems have overflow events and dump raw sewage into waterways. In 2020, the Hampton Roads Sanitation District dumped 2.5 million gallons of untreated wastewater into Shingles Creek in Suffolk when a standby pump failed, and almost 7 million gallons into Back Creek in York County after internal corrosion caused a 60-inch pipeline to collapse.5

The Environmental Protection Agency, Virginia State Water Control Board, and Lynchburg negotiated a Long Term Control Plan in 1994 to eliminate 85% of that city's Combined Sewer Overflows. Timing of projects was based on the financial capacity of the city and the ratepayers of the wastewater system, to avoid a dramatic short-term spike in sewer fees. Lynchburg started by separating the combined pipes, so stormwater would no longer enter the sanitary sewer pipes. In 2020, the legislature mandated that Lynchburg speed up completion of projects required to eliminate 100% of its untreated discharges, with a final plan to be completed by 2024.

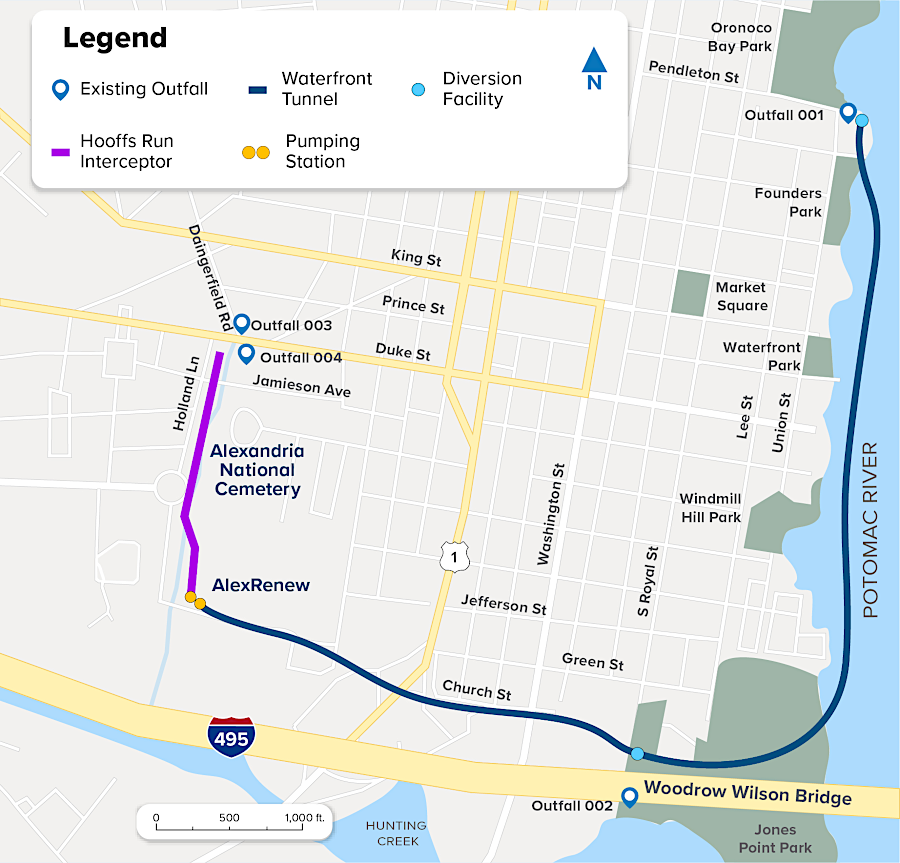

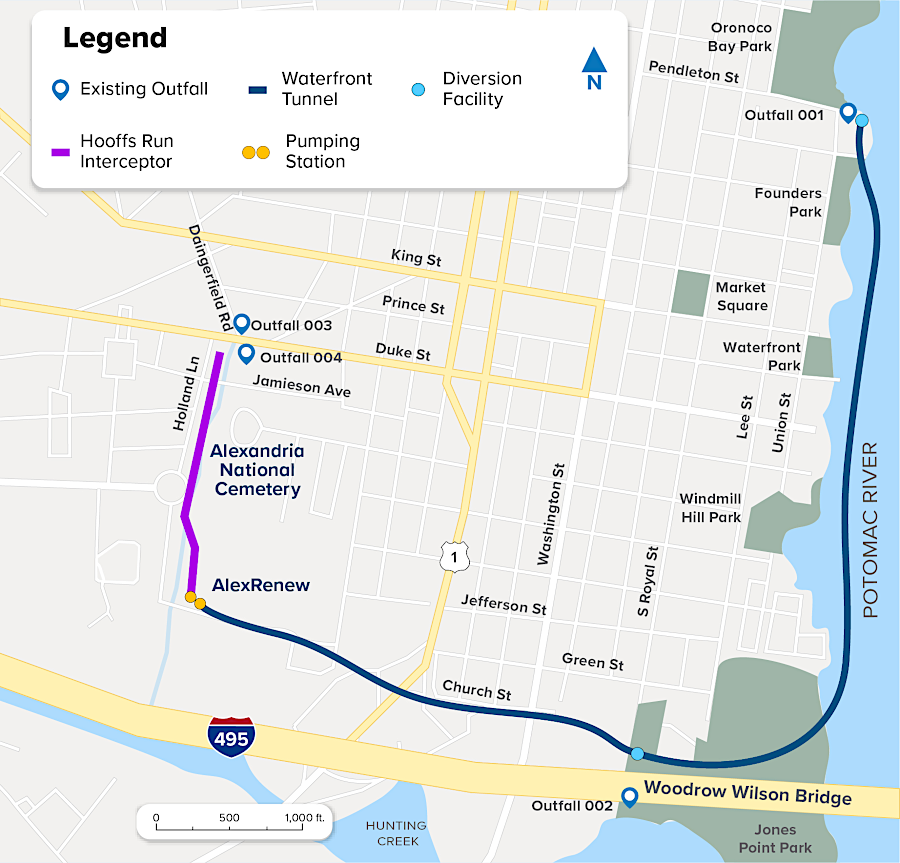

The General Assembly accelerated Alexandria's schedule with a mandate imposed in 2017 requiring overflows to be eliminated by 2025. To comply, Alexandria had to build a two-mile long, 100 foot deep tunnel along the waterfront and other facilities to intercept and store combined stormwater/sanitary sewage flows, in order to transport them to the wastewater treatment plant rather than discharge to the Potomac River.6

Alexandria had to build a tunnel and interceptors to meet the 2025 deadline to eliminate discharges from the Combined Sewer Overflow system

Source: AlexRenew, Alexandria's Current Combined Sewer System at a Glance (November 30, 2021)

The 2020 General Assembly also mandated that Richmond finish its sewer system projects and stop discharges by 2035. The city had eliminated 90% of its overflows by 2022. However, members of the 2022 General Assembly proposed that Richmond must meet a 2030 deadline.

The major challenge for Richmond was the extra $1 billion in cost. Without additional funding, a faster deadline would require ratepayers to pay 300% higher sewer bills to fund construction of additional storage facilities for combined stormwater/sanitary sewage. At the time, one-quarter of Richmond residents reported income levels below the poverty line and the city lacked the capacity to borrow the money required to meet a 2030 deadline.

City officials also noted that Richmond required more time than Alexandria to engineer a complex set of pipes and tunnels. A news story summarized the difference:7

While Alexandria is working to remediate four outfalls, Richmond has 25, a number it has cut from an original tally of 46. While Alexandria's combined sewer system drains an area of 0.8 square miles, Richmond's serves 19 square miles, including some 950 miles of pipe with an average age of 114 years. And while Alexandria's plans hinge on the construction of one extremely large tunnel for sewer overflows, earlier plans for Richmond have included as many as five.

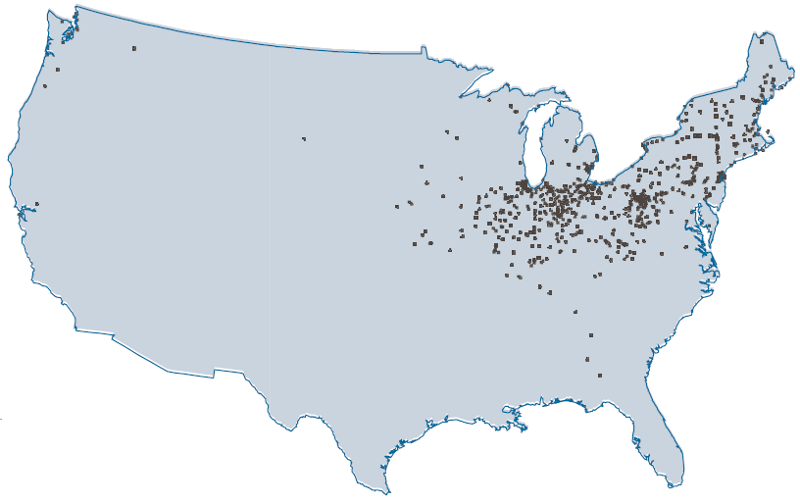

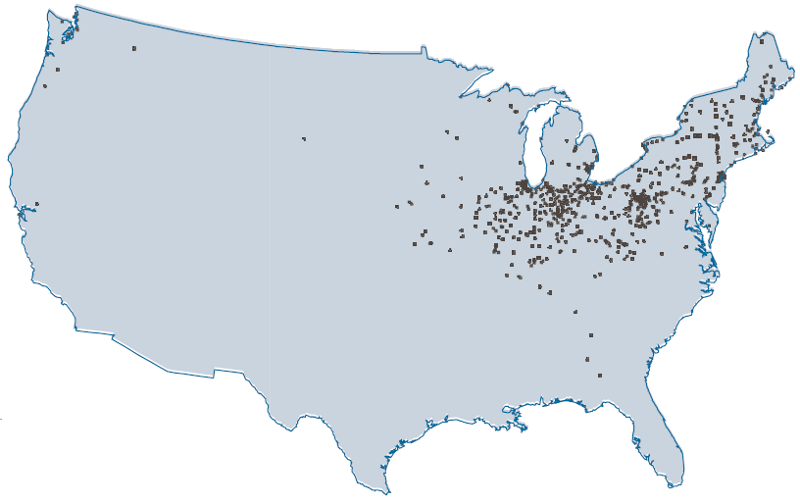

722 communities had CSO systems in 2004

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, 2004 Report to Congress: Impacts and Control of CSOs and SSOs, Chapter 2

Links

- Alexandria

- DC Water

- Environmental Protection Agency

- General Assembly

- Lynchburg

- Richmond

- Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ)

- Water Environment Foundation

- YouTube

in Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) systems, rainwater gets mixed with untreated sewage and dumped into nearby waterways

Source: District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (WASA), WASA’s Recommended Combined Sewer System Long Term Control Plan (Figure 2)

References

1. "Combined Sewer Overflows in the Commonwealth," General Assembly, Senate Document 40, 1990, p.3, http://leg2.state.va.us/dls/h&sdocs.nsf/By+Year/SD401990/$file/SD40_1990.pdf (last checked October 4, 2013)

2. "Senator pushes to speed up Richmond combined sewer fix," Virginia Mercury, February 14, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/02/14/senator-pushes-to-speed-up-richmond-combined-sewer-fix/ (last checked February 14, 2022)

3. "Combined Sewer Overflows - Nine Minimum Controls," Environmental Protection Agency, http://cfpub.epa.gov/npdes/cso/ninecontrols.cfm?program_id=5 (last checked October 4, 2013)

4. "DC Water Just Finished Digging a 5-Mile Tunnel 100 Feet Below the City," WAMU, April 27, 2021, https://dcist.com/story/21/04/27/dc-water-finishes-digging-tunnel-stop-flooding-sewage-overflow-anacostia-river/ (last checked May 5, 2021)

5. "Millions of gallons of sewage overflowed during recent heavy rain, HRSD says," The Virginian-Pilot, September 4, 2020, https://www.pilotonline.com/news/environment/vp-nw-hrsd-sewer-overflow-20200924-uoe2af52vrarpar4whzfhatod4-story.html (last checked September 25, 2020)

6. "Holistic Approach," Municipal Sewer and Water, July 2013, http://www.mswmag.com/editorial/2013/07/holistic_approach; "Virginia regulators approve Alexandria sewer repair plan," Washington Post, July 2, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/virginia-regulators-approve-alexandria-sewer-repair-plan/2018/07/02/8647c680-7e23-11e8-b0ef-fffcabeff946_story.html (last checked February 14, 2022)

7. "Senator pushes to speed up Richmond combined sewer fix," Virginia Mercury, February 14, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/02/14/senator-pushes-to-speed-up-richmond-combined-sewer-fix/ (last checked February 14, 2022)

Waste Management in Virginia

Virginia Places