Orange and Alexandria Railroad route south of Bull Run, before "Tudor Hall" evolved into Manassas

Source: Library of Congress

Orange and Alexandria Railroad route south of Bull Run, before "Tudor Hall" evolved into Manassas

Source: Library of Congress

Manassas was created by accident. An economic depression forced the construction of an unplanned railroad junction.

The Manassas Gap Railroad was not intended to connect with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. A level roadbed for the Manassas Gap Railroad was graded through Fairfax and Prince William counties, but the Panic of 1857 forced the backers of the Manassas Gap Railroad to economize. Costs for construction of 20-25 miles of track was eliminated by the decision to intersect the O&A at a place that was named Manassas Junction.

investors planned for the Manassas Gap Railroad to have its own, separate track from Alexandria rather than use the Orange and Alexandria Railroad

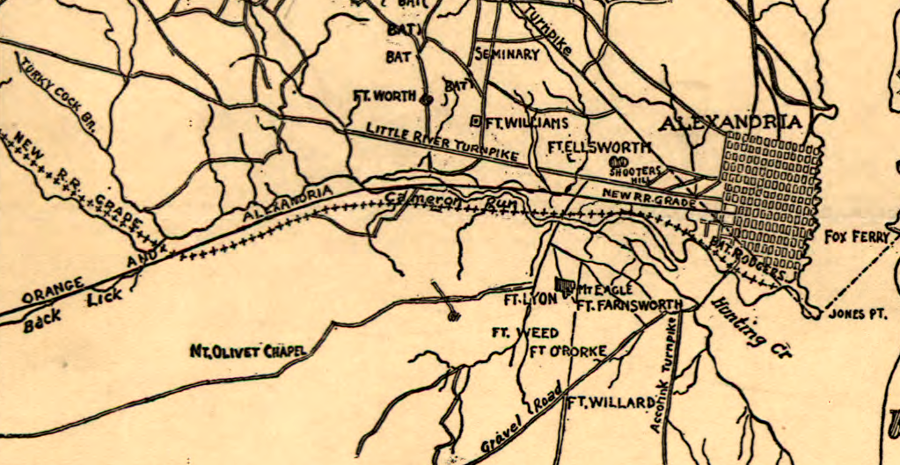

Source: Library of Congress, Map of fortifications and defenses of Washington (1865)

In the Civil War, the Confederates burned the facilities at the junction twice, in March and August of 1862. During the Overland Campaign of 1864-64, when Grant finally captured Richmond, the site was largely abandoned. After the Civil War, however, the junction developed into a bustling community. It was chartered as a town in 1875 (it became an independent city in 1975). In 1892, Manassas managed to get the county seat moved from Brentsville. Brentsville had been bypassed by the O&A Railroad because it was on a high spot, and railroads were constructed to avoid hills wherever possible. Unlike Warrenton, county seat of Fauquier, Brentsville was unable to get a spur line built to the county seat and, in the end, disappeared from the map.

Manassas is one of the few pre-Civil War railroad junctions. If you want to be certified as a card-carrying geographer familiar with the development of Virginia, you must be thinking "Gee, why were there so few railroad junctions back then?"

The rail network in the Shenandoah Valley shows most clearly that railroads were developed by Tidewater cities to steer traffic to competing ports on the Fall Line. After 25 years of intensive railroad construction in Virginia, in 1861 no track ran the length of the Shenandoah Valley

The tiny, undercapitalized Winchester and Potomac railroad connected Winchester and the "lower" Shenandoah Valley to Harpers Ferry and ultimately Baltimore. There was a totally separate section of the Manassas Gap Railroad further south, connecting Mount Jackson and the middle valley with Front Royal and ultimately Alexandria. Even further south, "up" the Valley, there was a separate section of the Virginia Central connecting Covington to Staunton, Waynesboro, and ultimately Richmond.

But prior to the Civil War, there was no railroad track connecting Covington to Mount Jackson, or connecting Mount Jackson to Winchester. The path of the Great Wagon Road/Wilderness Road used by Daniel Boone and thousands of others (now Route 11 and Interstate 81), the easiest topographical route from the Shenandoah Valley to a port handling ocean-going ships, was ignored.

Why? Cities like Alexandria were not seeking to build a transportation infrastructure for the overall benefit of the state, even though 40-60% of the railroad funding was provided by the Virginia General Assembly. Separate tracks were built through the gaps in the Blue Ridge in Northern Virginia (Manassas Gap) and Central Virginia (After Gap, near Charlottesville) to funnel Virginia farm goods to Virginia ports, rather than encourage trade with Baltimore or (horrors!) Philadelphia.

After crossing the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley, the Manassas Gap Railroad could have been built to the north, rather than south towards Mount Jackson. However, the railroad was not connected to existing railroads at Winchester or Harper's Ferry because pre-Civil War Virginia politicians blocked projects that would steer trade to Baltimore rather than Alexandria. In Virginia, local political concerns carried great weight in railroad construction because most capital funding came from local sources. Virginia lacked a cadre of urban investors and financiers with a "big picture," and who could afford to build a railroad system based on just return-on-investment decisions.

After the Civil War, Northern financiers gained sufficient economic leverage and political influence in the General Assembly to connect the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad to the Pennsylvania Railroad in Alexandria. Pennsylvania and New York capitalists also built a new north/south railroad in the Shenandoah Valley (it became the Norfolk and Western in 1881-2), creating a link between Manassas and Hagerstown, Maryland (the "B Line" of today).

In Alexandria, the competing railroads connecting to Washington, western Loudoun County, and Manassas/Mount Jackson all had separate terminals. Different investors were not inclined to share traffic with their rivals, even when they were located in the same cities. "Union Stations," providing a common passenger terminal for more than one railroad, came later.

The failure to connect railroads ensured wagon drivers ("draymen") had work hauling products between train stations. It also had military consequences. Prior to the outbreak of fighting in the Civil War, Robert E. Lee , working at the time as the military advisor to the governor of Virginia, was unable to get the owners of the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) and the Orange and Alexandria (O&A) railroads to build a piece of track connecting them. As a result, when the Union Army occupied Alexandria on March 24, two valuable locomotives were isolated on the AL&H.

To keep them from the Yankees, the locomotives were driven west away from Alexandria, removed from the AL&H tracks, and rolled/carried across Loudoun and Fauquier counties to the Manassas Gap railroad at Piedmont Station (now Delaplane).

Today, the old Manassas Gap Railroad is part of the Norfolk Southern.

The track crossing the Blue Ridge between Manassas and Front Royal is known as the "B Line." Branches of the Piedmont Division of the Norfolk Southern are labelled in order, stretching south from Washington DC. The old Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire (today's Washington and Old Dominion biking trail) was the first branch line south of Washington, so it was the A Line. The second branch leaving at Manassas for the Shenandoah Valley became the B Line.