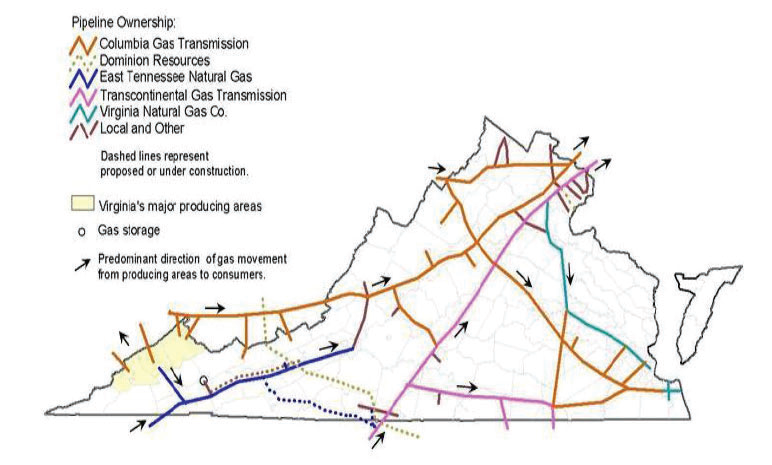

natural gas pipelines move gas from areas of excess supply to areas with sufficient customer demand

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, 2018 Virginia Energy Plan (Figure 14, p.51)

natural gas pipelines move gas from areas of excess supply to areas with sufficient customer demand

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, 2018 Virginia Energy Plan (Figure 14, p.51)

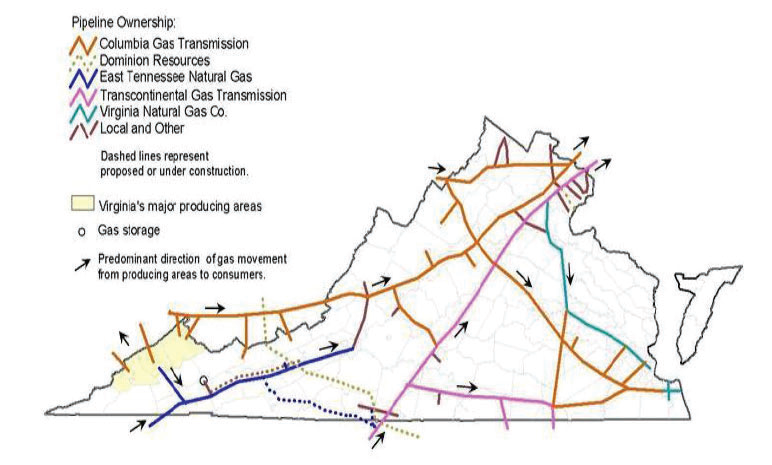

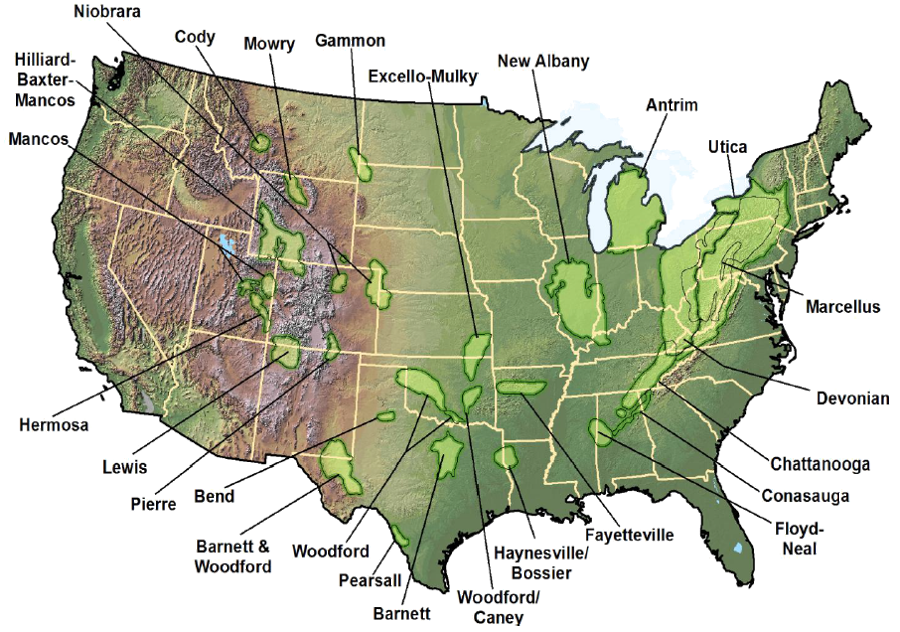

Starting in the 1990's, the development of the fracking process for "tight gas" formations led to a dramatic increase in the supply of natural gas from domestic resources. The Marcellus and Utica shale formation on the western edge of the Appalachians provided a major increase in supply for the urban markets on the East Coast, triggering plans for new pipelines across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Virginia.

as the natural gas in the Marcellus and Utica basins was developed through fracking, new pipelines were constructed to transport the gas to customers

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, New pipeline projects increase Northeast natural gas takeaway capacity

New pipelines were also needed to supply natural gas to new electrical generating plants, built in rural areas where large blocks of land could be purchased at low cost and power plant emissions would not violate Clean Air Act standards.

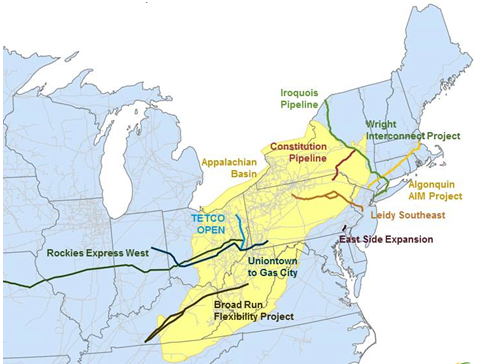

In 2003 East Tennessee Natural Gas (at that time partially owned by Duke Energy, and now by Spectra) built the Patriot Extension, a 24-inch (diameter) pipeline bringing natural gas from the main trunkline in Wythe County southeast into North Carolina. The Patriot Extension was expected to provide fuel to new power plants. Several were cancelled, including one by Dominion in North Carolina, one by Duke Energy at Austinville, and one planned by Cogentrix in Henry County.

There were still enough commitments to purchase gas over the next 25 years, from local gas delivery companies and other power plants, to justify approval of the 94-mile Patriot Extension by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The decisions to abandon plans for new power plants did cause Dominion Power to cancel its proposed Greenbrier pipeline, which was planned to go through southwestern Virginia from Giles to Henry counties.1

Spectra's East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline carries gas into southwestern Virginia

Source: Spectra Energy, East Tennessee Natural Gas

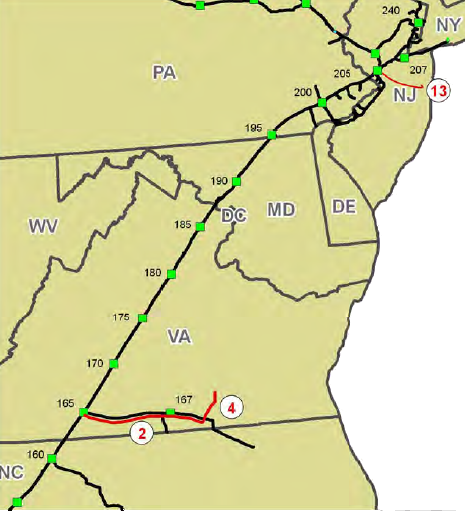

Transco built its own pipeline extension, the Virginia Southside Expansion, in 2015. That new 24-inch pipeline, parallel to an existing 20-inch pipeline, extended service 100 miles eastward from the compressor station known as Transco Station 165 in Pittsylvania County.

The Virginia Southside Expansion supplied gas to Dominion Power's new 1,300-megawatt electricity generating plant in Brunswick County. Dominion also relied upon Transco to bring natural gas to new electricity generating plants in Buckingham, Fauquier, Hanover, and Warren counties.

In 2024, Dominion proposed constructing a liquified natural gas plant and storage facility adjacent to the Greensville County Power Station to stockpile enough gas to supply the utility's Greensville and Brunswick generation plants. Construction costs were estimated to be $550 million. To repay borrowed money plus Dominion Power's authorized profit margin on infrastructure, ratepayers eventually could pay $1 billion for a facility that would be needed only if gas flow through the pipeline was interrupted.

Transco itself did not propose the storage project. Unlike Dominion Energy, Transco did not have the power to ask the State Corporation Commission to impose a Rate Adjustment Clause (RAC) or "rider" and require its gas-buying customers to guarantee the liquified natural gas plant and storage facility would be a profitable investment. If Transco raised its rates, customers might choose alternative ways to operate and purchase less natural gas from the company.

In contrast, Dominion Energy is a state-regulated utility with a monopoly to provide electricity within its service area. Its customers were not allowed to purchase electricity from an alternative supplier. The utility uses riders BW and GV to recover costs for constructing the Brunswick and Greensville power stations. It asked the State Corporation Commission to approve Rider GEN:2

the Virginia Southside Expansion pipeline (red line on map) allowed Transco to bring natural gas from Transco Station 165 in Pittsylvania County to a gas-fired power plant (#4 on map) constructed by Dominion in Brunswick County, 100 miles to the east

Source: The Williams Companies, Overview Map, Virginia Southside Expansion Project

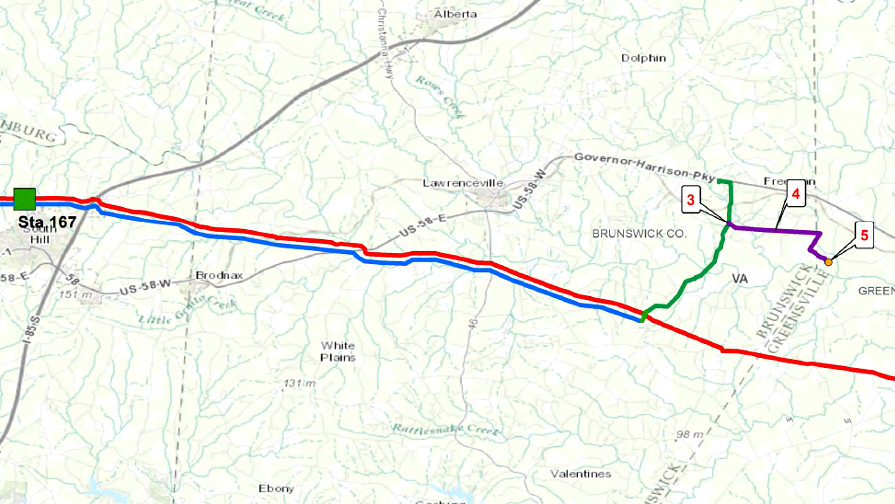

After Dominion committed to build another natural gas-fired electric generation facility in Greensville County, Transco proposed to extend the Virginia Southside Expansion pipeline an additional four miles. That Phase II extension, known as the Greensville Lateral, would provide gas to the new 1,580-megawatt power plant.

Phase II of the Virginia Southside Expansion pipeline would extend the pipeline four miles, so Transco could provide natural gas via the Greensville Lateral (purple line on map) to a second gas-fired power plant to be constructed by Dominion in Greensville County (5 on map)

Source: The Williams Companies, Overview Map, Virginia Southside Expansion Project

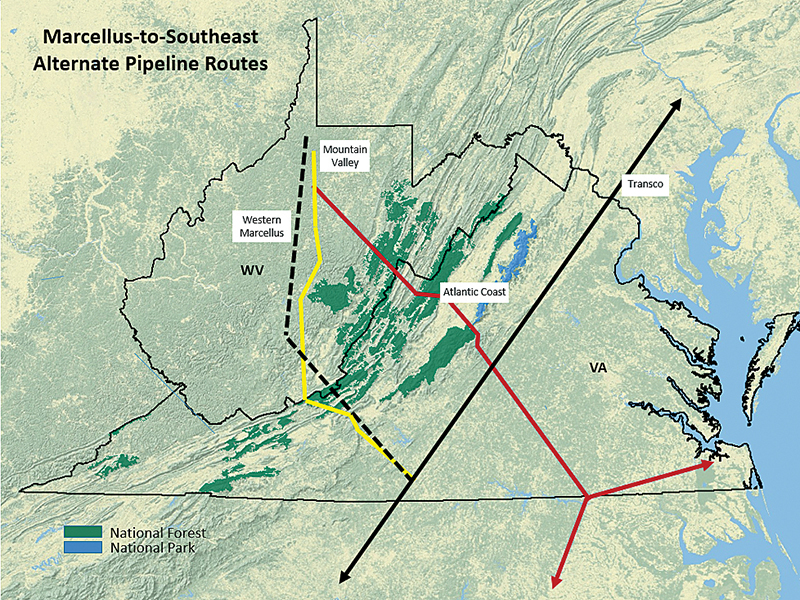

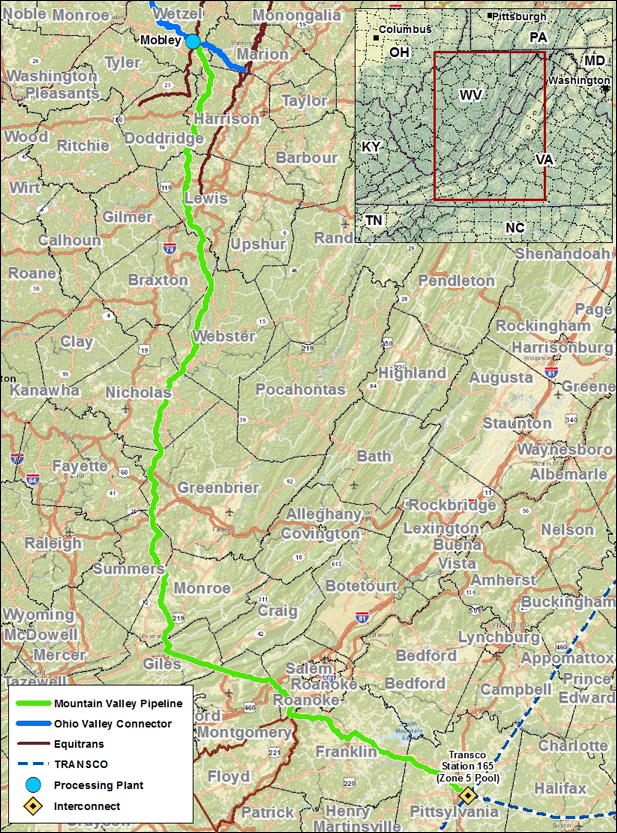

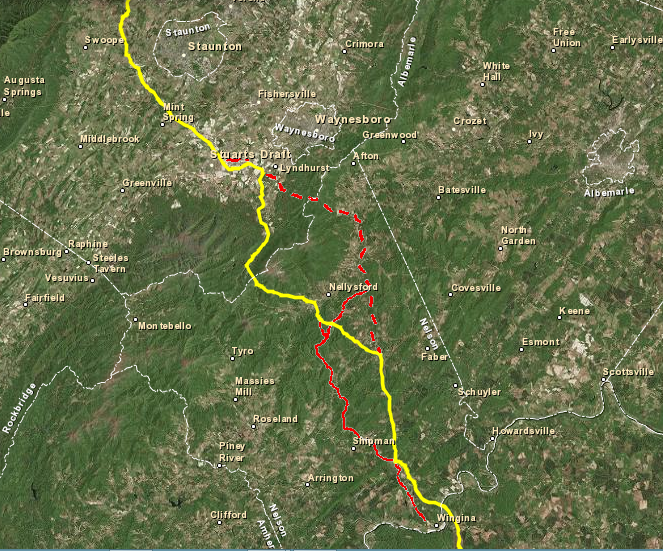

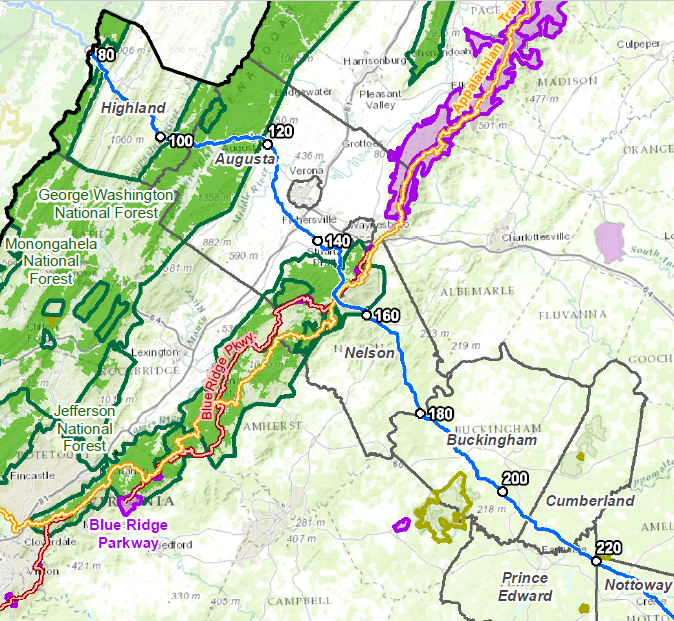

In 2014, pipeline companies announced three competing plans to bring Appalachian Basin shale gas to markets in Virginia and North Carolina. EQT Midstream Partners and NextEra Energy proposed the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Transco (Williams) championed the Appalachian Connector, and a partnership controlled by Dominion and Duke Energy was behind the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project.

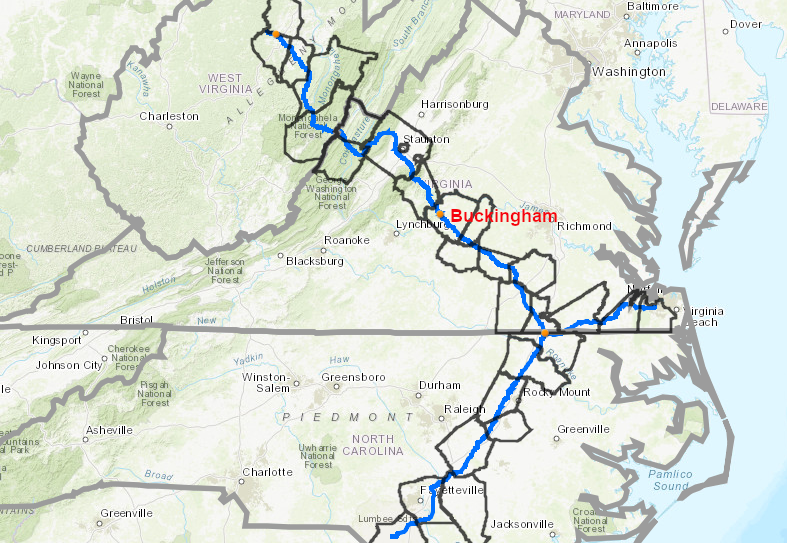

the Mountain Valley Pipeline and Atlantic Coast Pipeline were proposed to bring natural gas from the Marcellus fields to southern Virginia, Hampton Roads, and North Carolina

Source: Appalachian Voices, Pipe Dreams: The push to expand natural gas infrastructure

Building pipelines to deliver the new supply of gas to customers on the east side of the Appalachians requires identifying enough customers along a particular route to justify the investment. Between initial announcement and formally filing a route proposal with Federal/state agencies that must approve a project, pipeline companies revise the route in response to community objections and to avoid sensitive environmental/cultural areas. All announced projects create angst within the communities and rural areas which might be disrupted by construction and limitations on use of land above the buried pipeline.

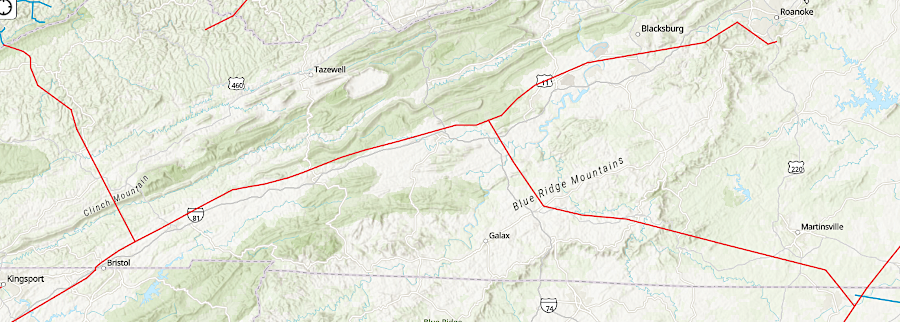

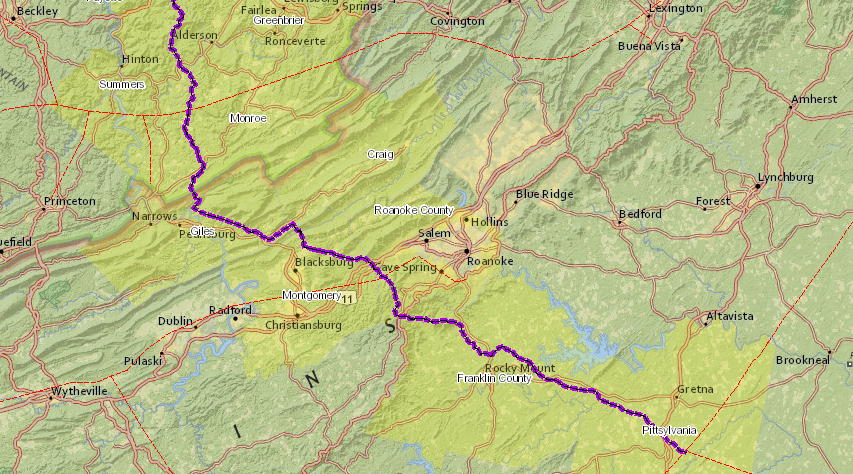

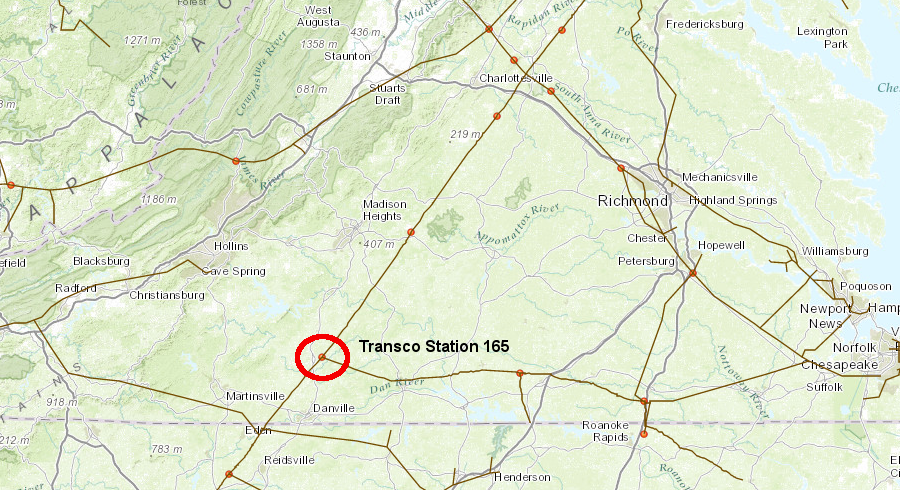

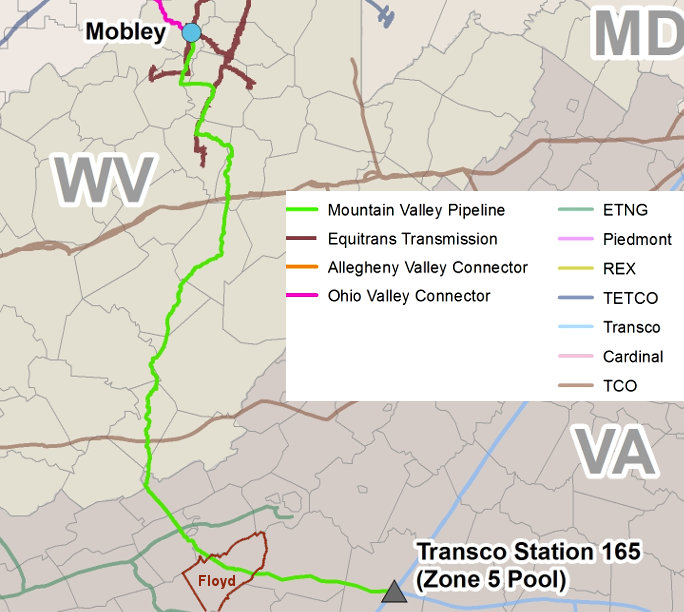

the Mountain Valley Pipeline would enter Virginia at Peters Mountain in Giles County on the West Virginia-Virginia border, and end at Transco Station 165 in Pittsylvania County

Source: Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition, Atlantic Coast Pipeline - Environmental Mapping System

The Mountain Valley Pipeline and the Appalachian Connector have a fixed end point. Competing pipeline companies planned to build from roughly the same location in West Virginia to the same destination, the compressor station known as Transco Station 165 on the existing Transco pipeline in Pittsylvania County. The proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline would cross the existing Transco trunk line further north.

the proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline and the Appalachian Connector would connect at Transco Station 165 to maximize access to a wide range of potential customers, but the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (owned primarily by Dominion and Duke Energy) would take a more-direct path to service Dominion and Duke Energy power plants in southeastern Virginia and North Carolina

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The companies that proposed the Mountain Valley Pipeline and the Appalachian Connector are competitors. The two pipelines would serve different buyers initially, and both must have enough commitments from initial customers to purchase the natural gas before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission will approve construction - but after the first contracts expire, the pipelines could be rivals. Both companies have rejected proposals to bury two separate 42-inch diameter pipelines in one common right-of-way.3

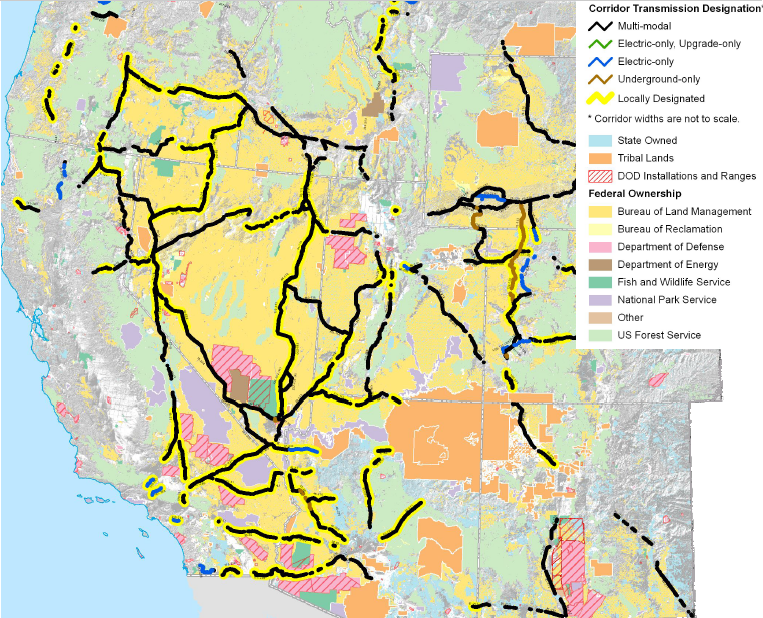

Using a common energy corridor would minimize impacts on landowners and the environment, but exacerbate competition. In the western states, where Federal lands were being affected by a series of energy transportation projects, the Bureau of Land Management has defined in advance the appropriate paths for electrical transmission lines and gas/petroleum pipelines.

in western states, companies choosing routes for new pipelines start with the pre-defined corridors established by the Federal government

Source: Bureau of Land Management, Eleven-State Map of Proposed Energy Corridors: 8" x 11" format

Some of the right-of-way for the failed Greenbrier project was proposed for the Mountain Valley Pipeline. That project would link shale gas production fields in West Virginia with customers in southern Virginia and perhaps North Carolina.

Public opposition to the Mountain Valley Pipeline developed quickly. It would create a cleared area as much as 75-feet wide through farms and forests in Giles, Pulaski, Montgomery, Floyd, Franklin and Henry counties on the way to a connection with the Transco pipeline in Pittsylvania County.

the proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline, to connect Marcellus and Utica natural gas supply to markets in the Southeastern United States, was revised from this original route to avoid Floyd county

Source: EQT Corporation, EQT and NextEra Energy Announce Southeast Pipeline Project

the revised route of the Mountain Valley Pipeline avoided Floyd County

Source: Mountain Valley Pipeline

Access to natural gas helps retain jobs, and Mohawk Industries stayed in Carroll County after the Patriot Pipeline provided low-cost energy. Floyd County still opposed the Mountain Valley Pipeline, in part because the pipeline's proposed right-of-way through the county was far from the business parks in the county where industries might locate. The pipeline planners reacted to the county's opposition and moved the proposed route north, proposing to cross Roanoke County instead of Floyd County.4

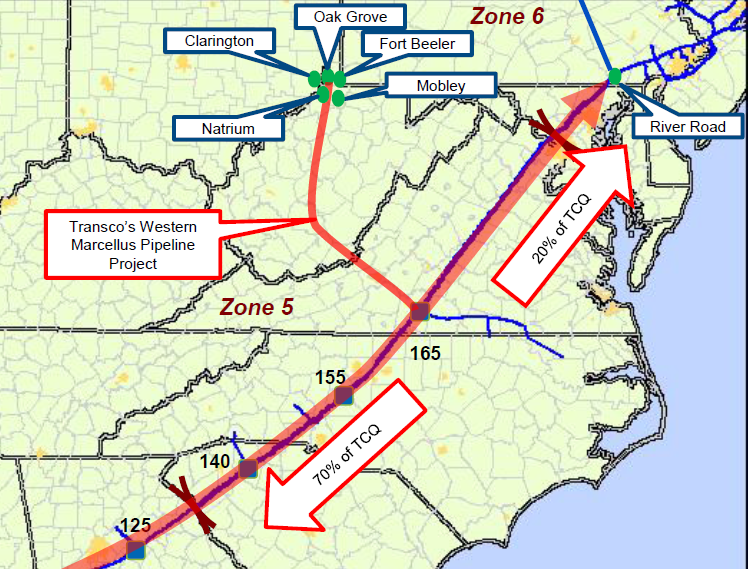

The owner of the Transco pipeline (Williams) proposed to build the Appalachian Connector, which was originally named the Western Marcellus Pipeline. It would go from West Virginia, travel through Virginia north of Roanoke, and end at the Transco compressor station 165 near Chatham. The Appalachian Connector pipeline project could transport gas from the Marcellus shale region as far south as Florida. The additional supply from the Appalachian fields could meet the needs of customers in the Southeast, allowing gas from the Gulf Coast gas to be redirected for export via Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) tankers.5

the Appalachian Corridor, originally named the Western Marcellus Pipeline, was proposed by the owner of the Transco pipeline to carry gas south

Source: Western Marcellus Pipeline Project

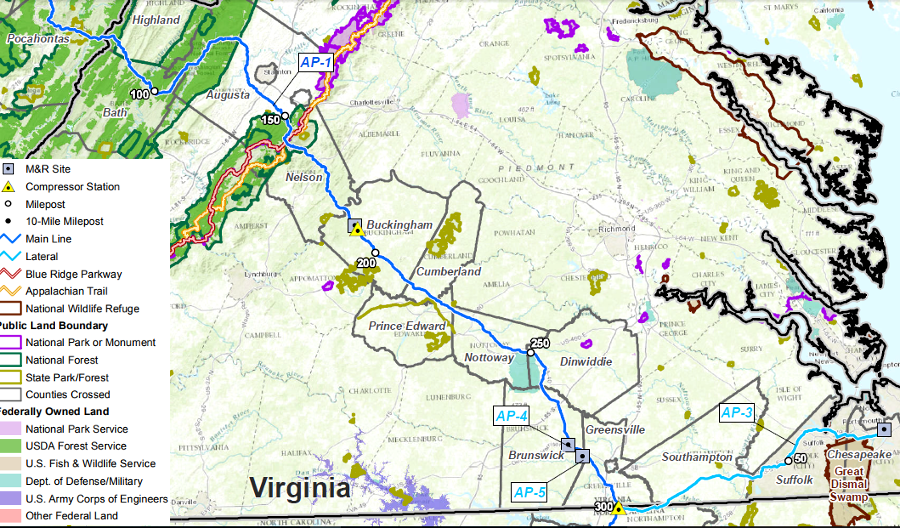

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline initially was a $2 billion project called the Dominion Southeast Reliability Project It was proposed by Dominion Energy to transport shale gas produced from the Marcellus/Utica formations to Dominion's power plants and other customers.

Duke Energy joined as a partner with an initial 40% share in the project. That utility has old coal-fired power plants in North Carolina to replace, and plans to burn more gas and less coal in its new facilities. The project then grew into a $5 billion proposal to construct a 42-inch, 450-mile pipeline from West Virginia to supply Dominion and Duke Energy power plants in Virginia and North Carolina.

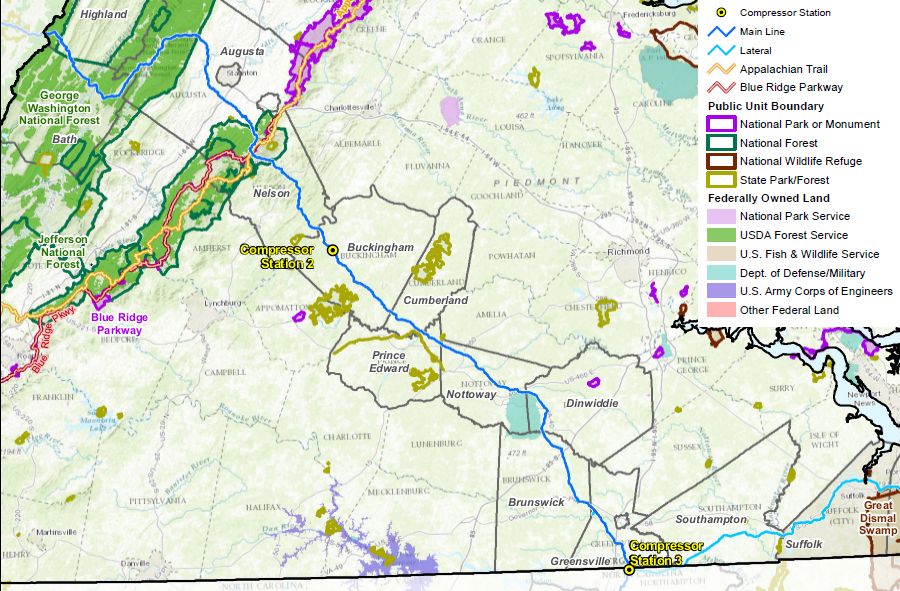

the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline included two compressor stations in Virginia

Source: Atlantic Coast Pipeline

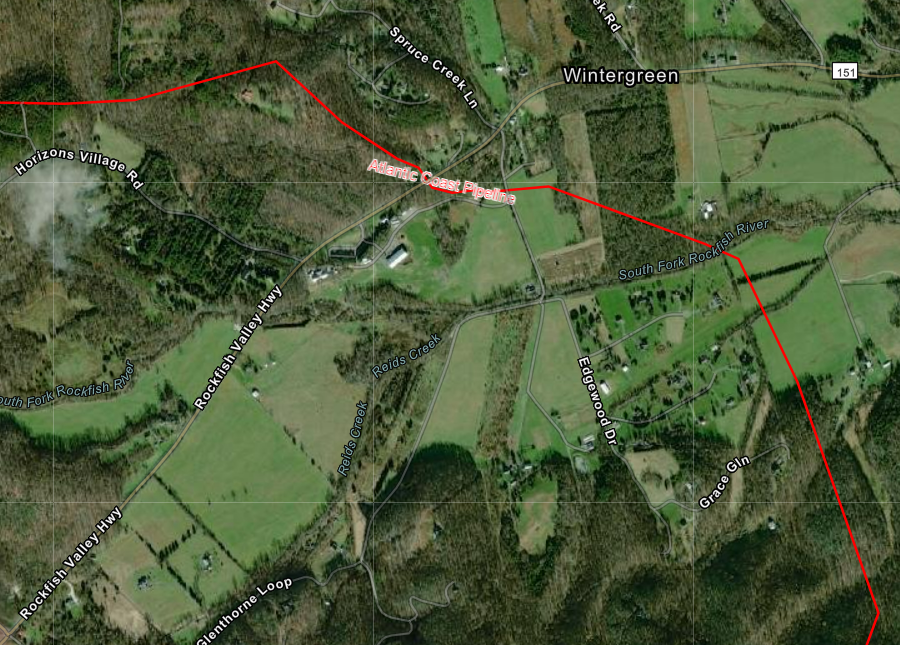

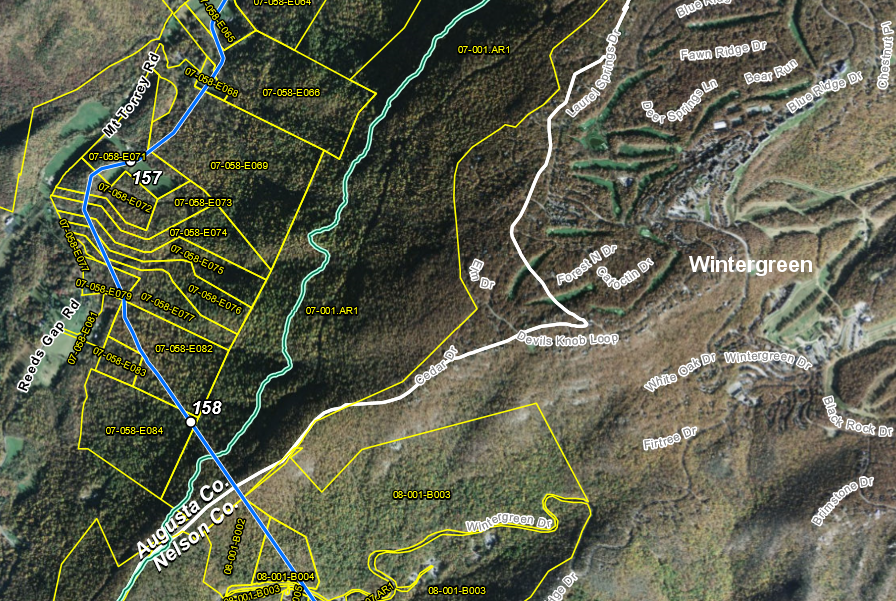

in Nelson County, the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline would cross Rockfish Valley just south of Wintergreen

Source: Chesapeake Climate Action Network, Eastern VA Anti-Pipeline Education Map

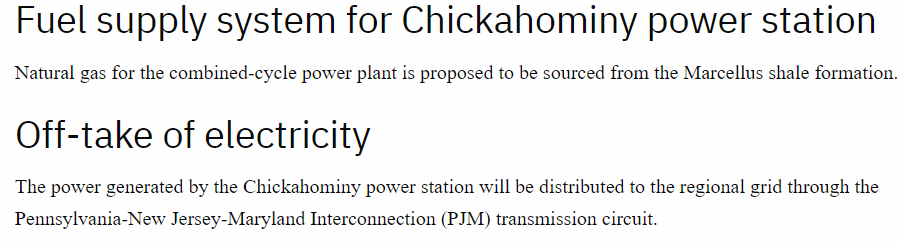

The route would pass through Virginia between Highland and Greensville counties. A 20-inch connection would extend delivery to Hampton Roads for distribution to customers by Virginia Natural Gas. After the pipeline was proposed, two gas-fired power plants were proposed for Charles City County. Merchant power companies, competitors to Dominion Power, proposed the 1,060-MW C4GT (Charles City Combined-Cycle Gas Turbine) power plant and the larger, 1,650MW Chickahominy Power Station. They would be major consumers of the increased gas supply, increasing generation capacity to match the increased demand coming from data centers in the area. The State Corporation Commission had to issue each facility a certificate of public convenience and necessity, but not rates. Price of the electricity would be determined through competitive sales into the PJM grid.6

the proposed C4GT power plant in Charles City County (red X) would rely upon new gas supply from the Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Google Maps

a proposed gas pipeline would have connected Marcellus shale gas wells to the proposed Chickahominy Power Station

Source: NS Energy, Chickahominy Power Stations

The parent company of Virginia Natural Gas (AGL Resources, which became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Southern Company in 2016) signed on as a 5% partner in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project. By 2016, Dominion Power owned 48% of the proposed pipeline and Duke Energy had the remaining 47%.

An extension to South Hampton Roads from the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would create an alternative source to the current TC Energy (Columbia Gas) transmission pipeline that supplies South Hampton Roads. The competition might result in lower transmission costs for Virginia Natural Gas.7

the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline would carry shale gas through Highland County to Greensville County, with an extension to south Hampton Roads

Source: Dominion, Atlantic Coast Pipeline

by 2016, Dominion had adjusted the route of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Dominion, Atlantic Coast Pipeline- Maps

the Atlantic Coast Pipeline proposed to cross the Blue Ridge near the resort community of Wintergreen

Source: Dominion, Maps by County - High-resolution Aerial Maps

The alternative to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline for Virginia Natural Gas was to build its own new pipeline, running east from the Transco trunk pipeline to serve just the company's customers. Virginia Natural Gas lacked enough capacity to attract new industrial users, and the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project offered a way to increase supply while other companies would pay most of the transportation costs. As a 5% partner, the companies cost to increase the supply of natural gas to Hampton Roads would be substantially reduced.

Virginia Natural Gas officials had considered alternatives, including building parallel pipelines next to Dominion and TC Energy/Columbia Gas's existing pipelines. Bacon's Rebellion blog quoted Jim Kibler, president of the company:8

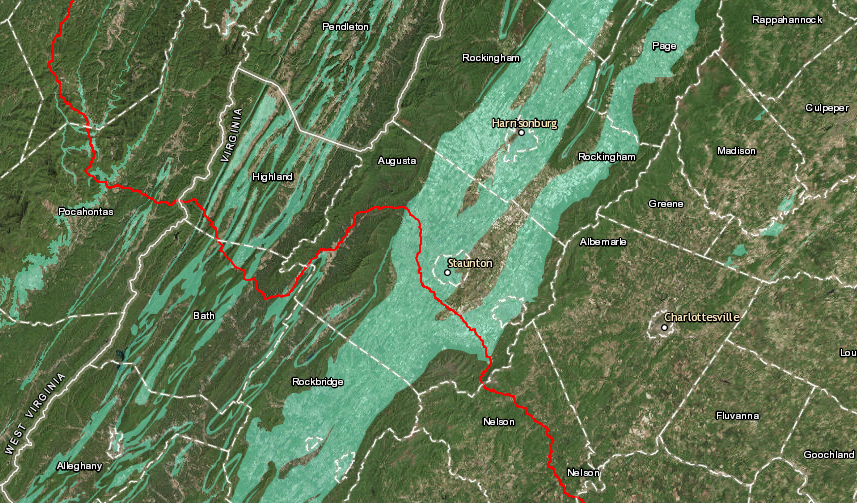

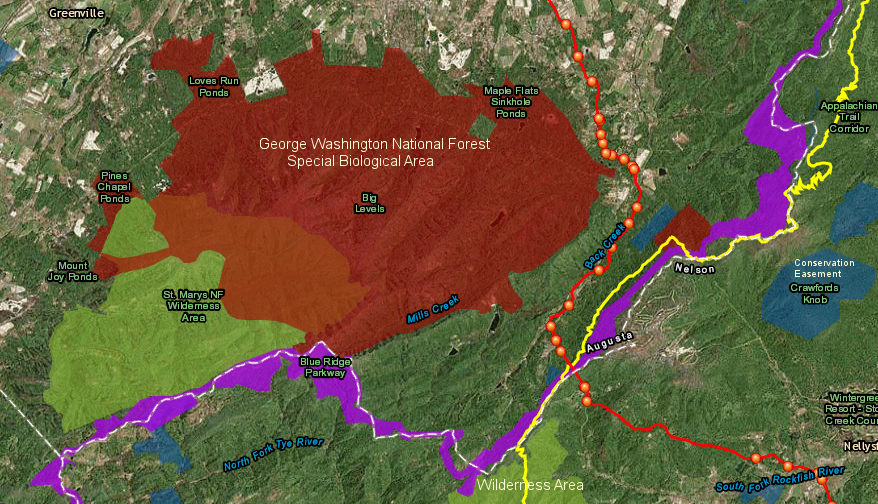

The environmental impacts of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline triggered strong opposition, especially in the karst regions of the Shenandoah Valley and where the pipeline would cross Blue Ridge. The pipeline would cut through sensitive natural habitats and cultural areas, including the Appalachian Trail and Blue Ridge Parkway.

the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would cross limestone bedrock with karst features (shaded light blue) in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province

Source: Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition, Atlantic Coast Pipeline - Environmental Mapping System

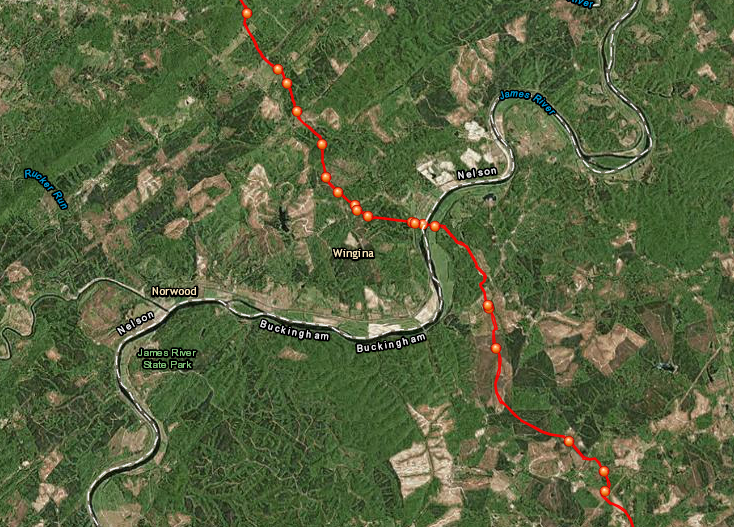

the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would require multiple stream crossings (shown as orange balls), including the James River

Source: Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition, Atlantic Coast Pipeline - Environmental Mapping System

the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was routed across the Blue Ridge to avoid areas protected by conservation easements, or designated as wilderness or special biological areas, but still had to cross the Blue Ridge Parkway and Appalachian Trail

Source: Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition, Atlantic Coast Pipeline - Environmental Mapping System

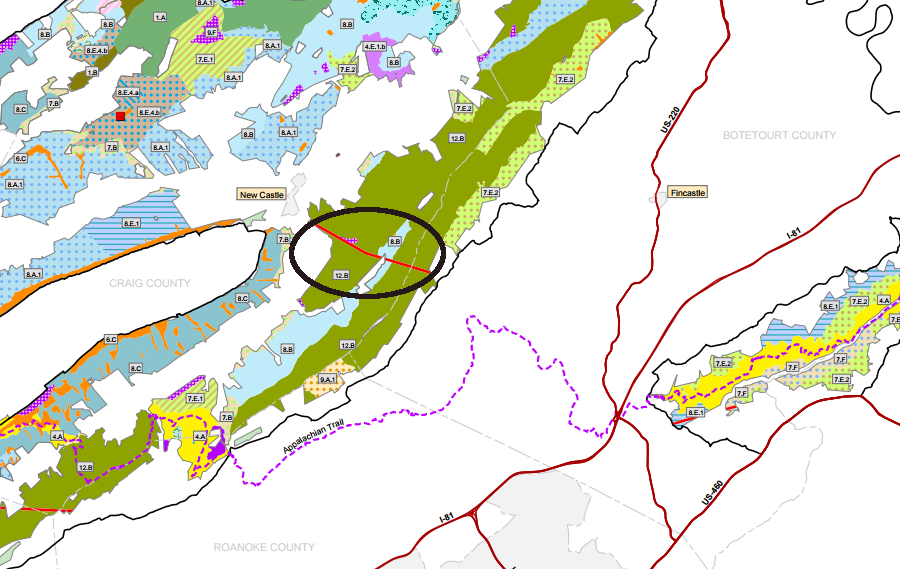

Opponents feared the US Forest Service would decide to minimize future opposition to new powerline and gas transmission lines by defining the route of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, Atlantic Coast Pipeline, or both as a Designated Utility Corridor. A right of way up to 1,000-feet wide through the Jefferson National Forest would reduce the number of areas impacted by energy transmission projects, but increase the impact in the one designated area.9

the Jefferson National Forest defined the location of a Designated Utility Corridor (red line) in 2004

Source: US Forest Service, :Final Environmental Impact Statement - Land and Resource Management Plan," Alternative I: Management Prescriptions (North Half)

One justification for the new pipelines was to increase competition by connecting a new source of gas, allowing Virginia and North Carolina customers to get better prices. Completion of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would force natural gas piped to eastern Virginia from the Gulf Coast to face significant competition from gas produced by fracking in the Appalachian Basin. Once its existing contracts with Transco expired, Dominion could use gas from Ohio rather than from Louisiana/Texas to supply its power plants in Buckingham, Brunswick, and Greensville counties.

The demand for natural gas in southern states peaks in the summer, when air conditioning is in common use. The demand for natural gas in the north peaks in the winter, when interior spaces are heated. The price of natural gas transported north from the Gulf of Mexico drops in the summer. The price of gas produced in the Marcellus Basin, which would be carried south by the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Mountain Valley Pipeline, drops in the winter.

Neither Duke Energy nor Dominion makes a profit on the fuel used to create electricity. As the costs of gas, coal, and other shift, the rates charged to customers are adjusted up or down. The fuel rate adjustment insulates the utilities from price spikes triggered by oil embargoes or other causes which utilities can not control, while ensuring that customers get savings when the costs of energy supplies drop.

If the utilities could purchase natural gas at lower prices, they could still benefit by lowering prices to industrial customers and selling more electricity. Unlike residential customers, industrial customers have options. If electricity is the low-cost option within the service area of a utility, then existing industries might expand and use more electricity. In addition, costs of electricity is a competitive actor for industrial companies when they choose to relocate or build new facilities.

Owning a gas pipeline could help the parent companies of investor-owned regulated utilities to make a greater profit. The Federal Energy Regulatory Authority (FERC) allows for a higher rate of return on capital invested in interstate pipelines for transporting natural gas, compared to the rate of return allowed by state regulators in Virginia and North Carolina for capital invested in electricity generation and distribution.

The parent companies of Dominion and Duke Energy anticipated making a 14% rate of return from their investment in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline transporting natural gas to their own electricity generating plants. When existing contracts with Transco expire, the utilities will be able to steer payments for transporting natural gas to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

Corporate subsidiaries of Dominion, including regulated utilities, committed to purchase 20% of the natural gas to be moved through the pipeline. The State Corporation Commission declined to examine the anticipated costs of that transmission, and declared that the issue would be addressed only when the utility asked for rates to be adjusted. That would occur after the $7 billion Atlantic Coast Pipeline was completed.

In 2017 the Sierra Club petitioned the State Corporation Commission to review any contracts between Dominion's different corporate units dealing with transport and purchase of natural gas, to ensure customers do not end up paying excessive prices.10

Plans by Dominion Power to build new gas-fired generation plants in Southside Virginia would lock in future demand for natural gas transmission, since the State Corporation Commission would add the facilities to the rate base used to set prices that the utility could charge customers for electricity.

Guaranteeing future profits for the holding companies that control both the new pipeline and the new power plants may not be in the public interest. Opponents to constructing the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) suggested that a new pipeline was not needed. The Southern Environmental Law Center asserted:11

The relative cost of the new pipeline vs. use/expansion of existing pipelines was a key economic argument:12

the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline route through Nelson County was altered after community reaction (red line shows previous proposed routes)

Source: Dominion, Interactive Map - Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Opponents also contended that shipping gas to Virginia was not cost-effective compared to alternatives. Dominion's planned upgrades to its own transmission line bring gas south from Pennsylvania could accommodate some of the growing demand. Those upgrades required new compression capacity, which generated opposition from neighbors in Loudoun County, but did not require clearing a new right-of-way through the Shenandoah Valley and across the Blue Ridge.13

Electricity could be generated from power plants built near the gas fields, then transmitted through the grid to industrial facilities in Hampton Roads. That option would require construction or expansion of overhead power lines, and the utilities would have to deal with public opposition to that new infrastructure. There were no options without impacts, no options that everyone would support.

The basic need for the extra gas to be moved to Virginia via the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was challenged successfully by pipeline opponents. In 2018, the State Corporation Commission rejected the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) submitted by Dominion's utility subsidiary to provide a framework for future investments. It noted that projections for electricity demand (load forecasts) had been "consistently overstated."

The state agency cited the projections by PJM Interconnection, the multi-state Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) that coordinates the movement of wholesale electricity. In 2018 PJM predicted a 0.8% compound annual growth rate in peak demand over the next 15 years, while Dominion predicted 1.4%.

An expert witness had testified on this issue a year earlier that the justification for the pipeline depended upon projected increases in demand for electricity, but:14

Dominion had a clear counter-argument. It claimed that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) was needed in order to diversify the sources of gas to meet current demand. Blogger James Bacon talked to the energy company's executives and reported:15

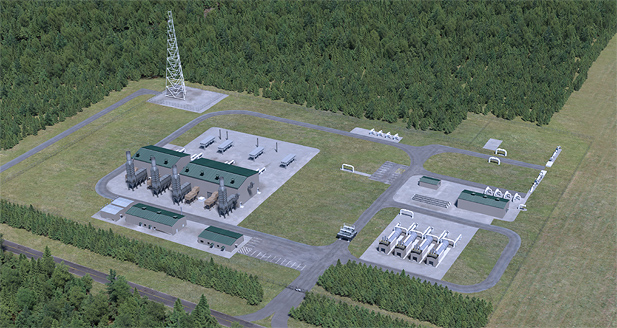

Opponents of the pipeline tried to block state approval of an air quality permit which Dominion needed for a compressor station in Buckingham County. The Virginia Air Pollution Control Board delayed its decision in order to assess claims that the preferred location, next to the African-American community of Union Hill, reflected environmental racism and if an alternative location would be feasible.

Dominion claimed the location of Compressor Station #2 (one of three for the pipeline) was necessary because the site was near an intersection with existing natural gas pipeline, and the landowner was willing to sell the needed 68 acres. The Virginia the Department of Environmental Quality recommended approval, and the site was already approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Buckingham Board of Supervisors.

The issue was highly politicized and drew national attention from activists. The state agency was deciding whether to authorize emissions from one new compressor station, but the opposition to that station was enhanced by the effort to block the entire 600-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

Just before the initial planned vote, Governor Northam replaced two members on the board who were not reliable supporters of the permit. The uproar ended with an announcement that his replacements would not vote on the issue. After a two-month delay, the Air Pollution Control Board approved the permit on a final 4-0 vote in January, 2019.16

pipeline company's representation of the controversial compressor station in Buckingham County

Source: Atlantic Coast Pipeline, Buckingham Compressor Station

yellow dots mark the locations of the three compressor stations on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Atlantic Coast Pipeline, ACP Construction News

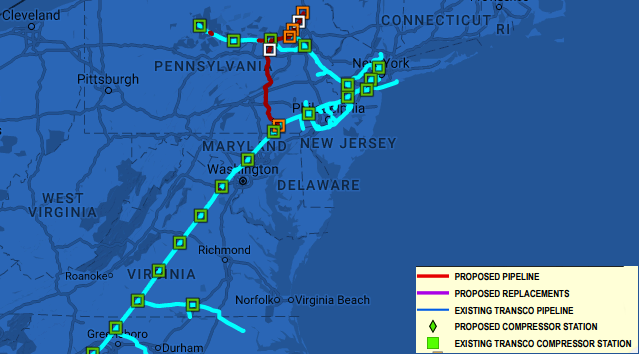

Transco reacted to the possible competition from Dominion and Duke Energy. In addition to the Appalachian Connector, Transco developed a second plan to ship Marcellus gas south. The Atlantic Sunrise pipeline would insert gas from Pennsylvania fields into Transco's trunk pipeline near the Pennsylvania-Maryland border. The extra gas would be piped south, reversing the direction of flow in the pipeline.

Dominion claimed there could be problems with the Transco proposal. The reliability of Transco's gas supply would be at risk due to bi-directional flow with a changing seasonal "null point," where pressure from the north equaled pressure from the south. Ensuring steady pressure to customers was cited as a justification for constructing the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.17

Court challenges delayed issuance of permits and forced the US Forest Service to revoke its authorization to cross the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. A Federal court also blocked the permit issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service for "incidental take" of endangered species. That action led to a voluntary suspension of Atlantic Coast Pipeline construction in December 2018. By 2019, costs for the project had risen to over $7 billion.18

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, based in Richmond, ruled in December 2018 that the U.S. Forest Service had no legal authority to allow the Atlantic Coast Pipeline to cross the Appalachian Trail, and the pipeline had not identified an alternative route. No pipeline across the trail had ever been authorized previously, and the court quoted Dr. Seuss' The Lorax in its decision:19

The US Supreme Court ruled in June, 2020 that the permit could be issued by the US Forest Service to tunnel below the trail. The trail was part of the National Park System, but the court ruled that it would require an "elusively metaphysical distinction" to deny the separate Federal agency the authority to grant a permit. Pipelines had already been authorized to cross the Appalachian Trail at 34 other locations, though all of those crossings were on non-Federal land or on land where easements were authorized before Federal acquisition.

Despite the legal victory, in July 2020 later the sponsors of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline cancelled the project. It had received approval by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in 2017, but more delay from continued legal opposition was expected. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit had overturned the Virginia Air Pollution Control Board permit for the gas compressor station at Union Hill in Buckingham County in January 2020, and opponents of the pipeline were engaged in a series of other cases which could require continued suspension of construction. A court case in Montana threatened to block the US Army Corps of Engineers from issuing its standard Nationwide 12 permits for pipelines to cross streams.

pipe was shipped to Virginia for use in constructing the Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Mark Levisay, D7K_1878-1

Initial cost estimates had been $4.5 to $5 billion. By the time the project was cancelled after six years of development, Dominion Energy and Duke Energy had spent $3.7 billion, and total costs were projected at $8 billion.

Dominion also announced plans to sell most of its natural gas assets, including 7,700 miles of natural gas pipelines - but not its stake in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The utility planned to retain only natural gas infrastructure which was regulated by state authorities, and focus on a transition to clean energy sources such as offshore wind.20

the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline (red line) would bring Pennsylvania gas south to Virginia, reversing flow in the Transco pipeline

Source: Transco, Atlantic Coast Pipeline- Maps

Other planned pipeline projects were announced but not built. Like the Greenbrier project, they failed to identify enough long-term customers to justify the high initial cost of building a pipeline. One proposal to transport Marcellus Shale gas to power plants in southeastern Virginia and North Carolina was announced in 2014, but was quickly dropped due to competition.

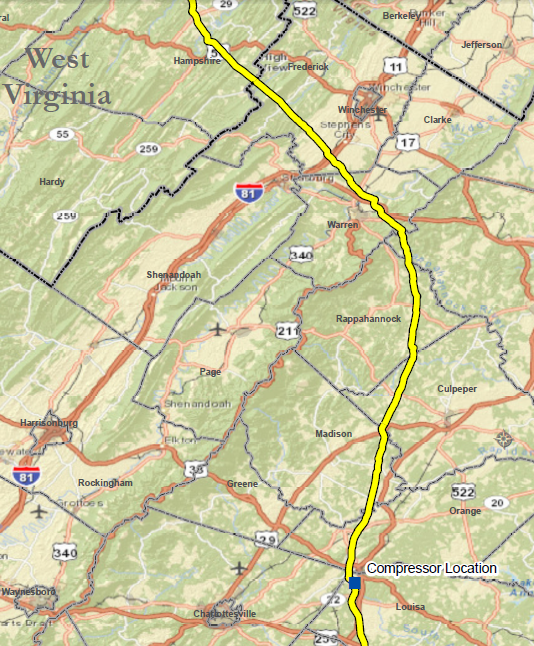

Spectra Energy proposed to build a pipeline through Virginia from Frederick to Mecklenburg counties. The route included land at Montpelier, the historic plantation of President James Madison. However, no formal application was submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). After Duke Energy and Dominion joined together on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline to supply their own power plants, Spectra dropped its proposal.21

Spectra's plans to build a gas pipeline across the Blue Ridge and Piedmont in undeveloped areas of Warren, Fauquier, and Rappahannock counties alarmed the Piedmont Environmental Council, but the project was quickly dropped when the expected customers (Dominion and Duke Energy) proposed their own Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Piedmont Environmental Council, Maps of the Spectra Energy Gas Pipeline Proposal

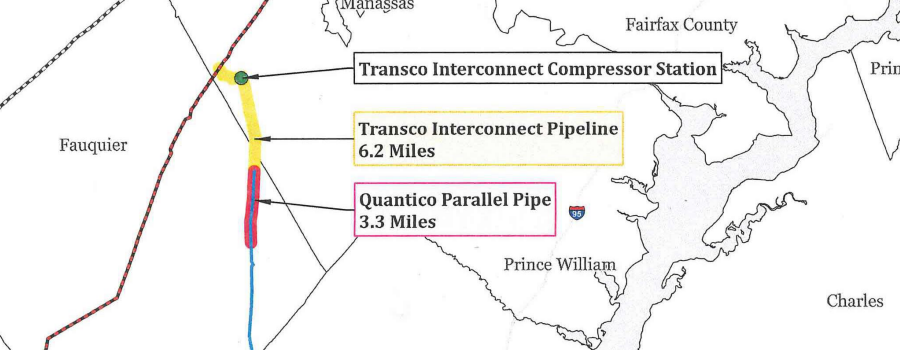

In 2018, Williams announce plans for the "Southeastern Trail Expansion Project," to increase the capacity of the Transco pipeline to move gas south to customers in Georgia. The company had already expanded its ability to transport gas in Pennsylvania, with the Atlantic Sunrise and Leidy Southeast projects. The Southeastern Trail Expansion Project propose expanding compressor capacity at three stations in Virginia, and building a 42" pipeline "loop" in Prince William and Fauquier counties.22

Compressor Station 185 on the Transco Pipeline is located south of I-66 near Manassas

Source: Transcontinental Gas Pipeline application for Manassas Loop, Maps of the Spectra Energy Gas Pipeline Proposal (Drawing F-MANA-D-TM-01)

On the Eastern Shore, the Delmarva Pipeline Company proposed a new pipeline in 2017. The gas would come from the Transco pipeline at or near Gate 196, and the new pipeline would transport it south through Maryland into Accomack County. The "No Eastern Shore Pipeline" group feared it might provide natural gas for a new electrical generating station to be located near Denton, Maryland.

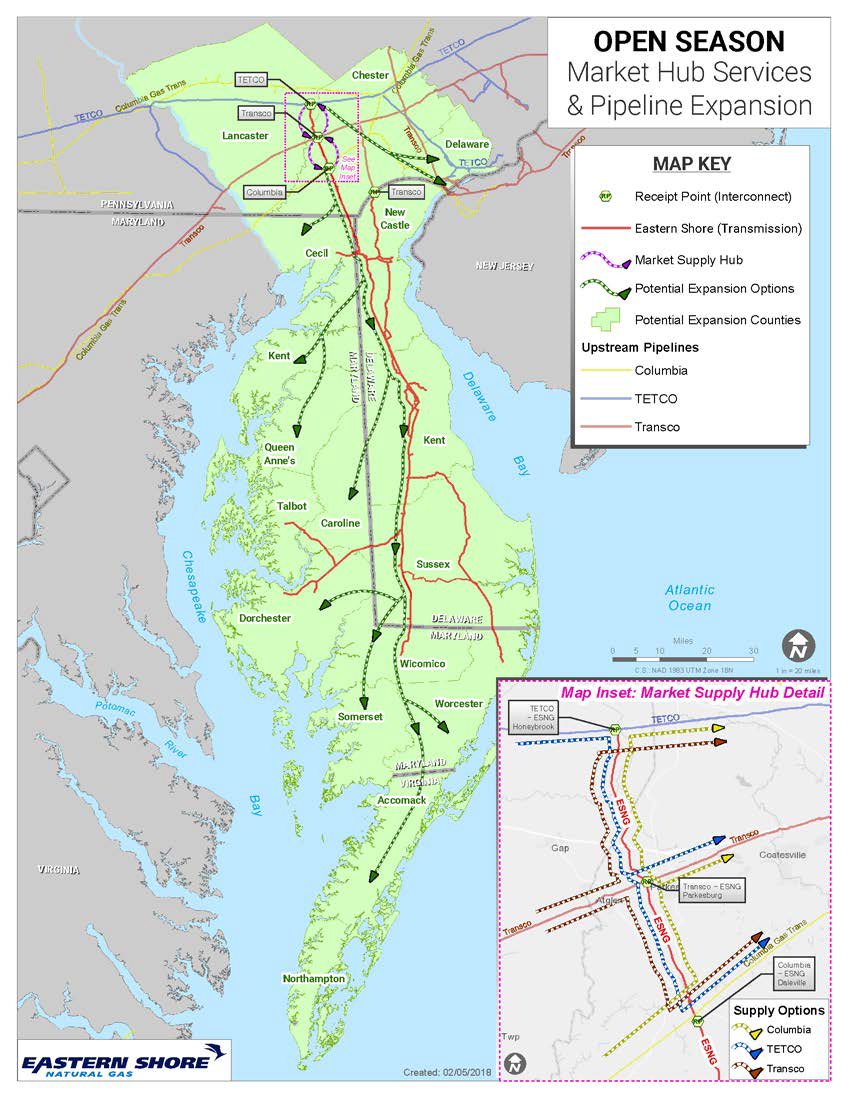

Eastern Shore Natural Gas Company then announced a competing proposal to expand its existing pipeline network on Maryland's Eastern Shore. The expansion could tap into three major transmission pipelines near the Maryland-Pennsylvania border, and the Eastern Shore Natural Gas Company network would be extended from Salisbury, Maryland south all the way into Northampton County.23

The proposed new pipelines could deliver gas from the Gulf Coast or from the Marcellus Basin, since the new supply from fracking was creating more price competition.

Delmarva Pipeline Company proposed a new pipeline south into Accomack County in 2017

Source: Delmarva Pipeline Company, Open Season Notice for Firm Service, August 21st, 2017 - October 22nd, 2017

in 2018, Eastern Shore Natural Gas Company proposed to pipe natural gas as far as Northampton County

Source: Eastern Shore Natural Gas, Market Hub Services & Pipeline Expansion

pipeline opponents offered a simple message

Source: No Eastern Shore Pipeline, Digital Tools

Pipeline expansion proposals ran into objections from landowners. Expectations of increasing natural gas sales were inconsistent with efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by ending the use of fossil fuels. Though burning natural gas generates less carbon dioxide that burning coal, the emissions still exacerbate climate change.

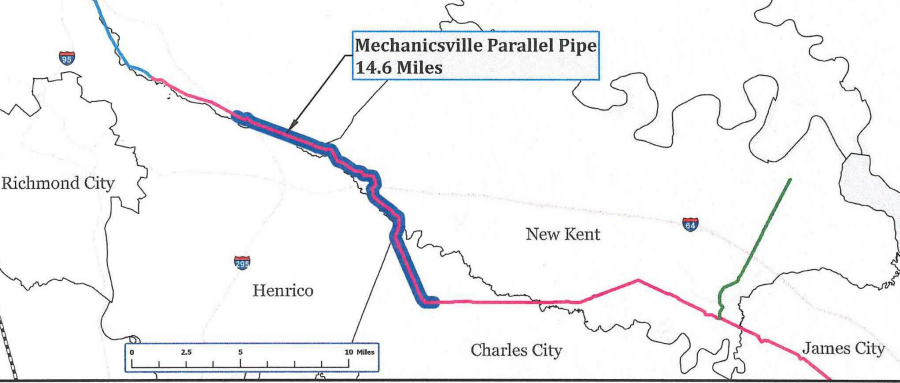

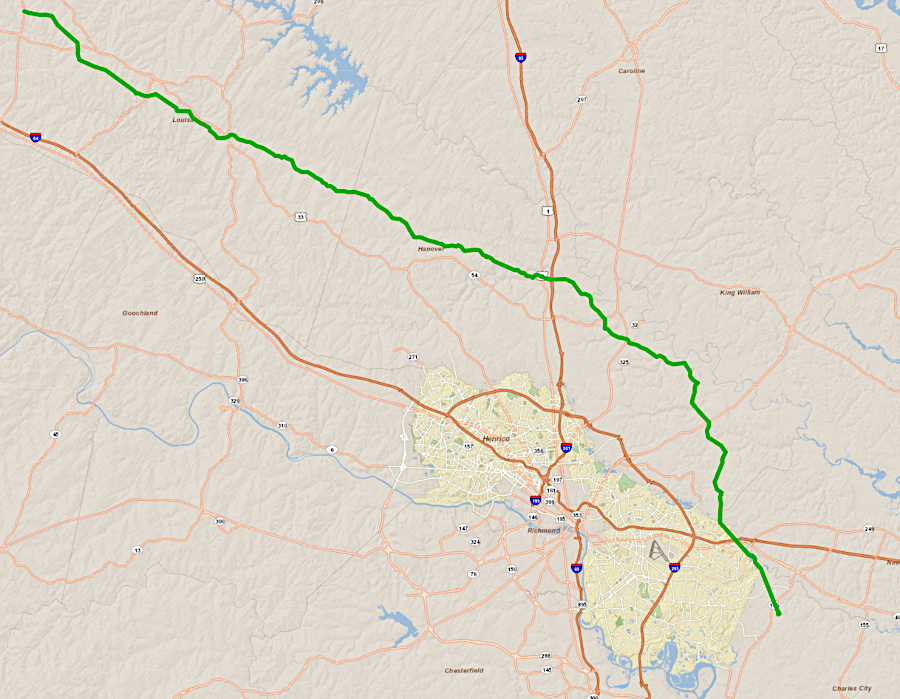

Delays in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project may have been one reason that Virginia Natural Gas proposed to expand its own pipeline in 2019. The company requested State Corporation Commission approval of the Header Improvement Project, connecting the Transco pipeline in Prince William County to the City of Chesapeake. The extra gas would flow through a pipeline on the Peninsula and cross underneath the James River to South Hampton Roads, and would fuel the proposed 1,060-MW C4GT power plant and the Chickahominy Power Station in Charles City County.

Construction would require 9.5 miles of new pipeline in Prince William and Fauquier counties, plus 14.6 miles of new pipe parallel to the company's existing VNG Lateral Pipeline in the Hanover, New Kent, and Charles City County. New compressor stations would be added in Prince William and Caroline county and in the City of Chesapeake.

the Header Improvement Project proposed to expand Virginia Natural Gas pipelines to move gas from Northern Virginia to Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Natural Gas, VNG Header Improvement Project

To finance the Header Improvement Project, the State Corporation Commission had to authorize an increase in the rates that Virginia Natural Gas customers would pay. The state agency required Virginia Natural Gas to prove that there was enough new demand for natural gas to justify the cost of building the project. However, the 1,060-MW C4GT power plant was a speculative venture without guaranteed financing, and the State Corporation Commission feared that the Header Improvement Project might be completed, but without new customers to buy new gas and help pay for the project.

In 2020, Virginia Natural Gas recognized that it could not meet the requirement to demonstrate demand and cancelled the Header Improvement Project. Balico LLC, which had proposed the Chickahominy Power Station, then tried to get the State Corporation Commission to authorize an 83-mile private Chickahominy Pipeline serving just their facility. That meant the pipeline would not have the right of eminent domain, so any single landowner could force a re-routing of the pipeline around their property.

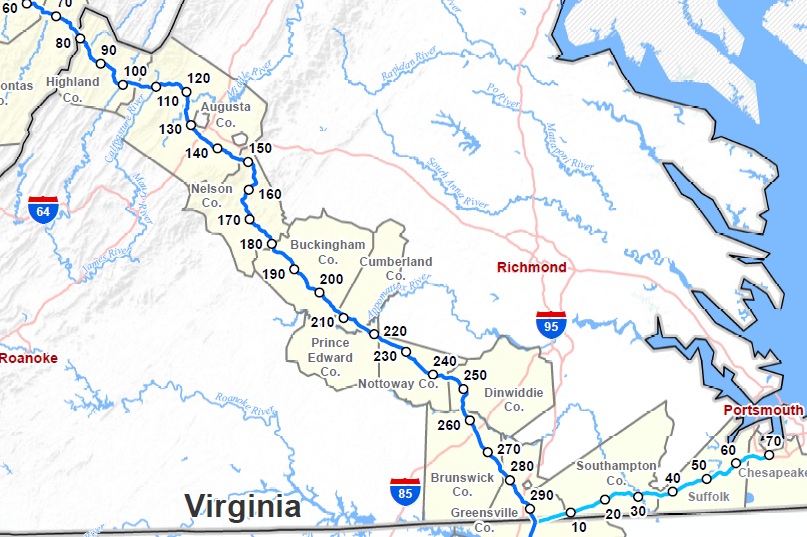

the Chickahominy Pipeline would transport natural gas from the Transco pipeline near Charlottesville to the Chickahominy Power Station

Source: Chickahominy Pipeline, Chickahominy Pipeline Map

The State Corporation Commission decided at the end of 2021 that the pipeline would be treated as a common carrier. The public review process would take time, and the company would be required to demonstrate that it had a reliable customer to purchase the gas before state approval would be issued.

Balico LLC sought to bypass the public utility approval process for the Chickahominy Pipeline, since it would serve just the Chickahominy Power project

Source: Chickahominy Pipeline, Frequently Asked Questions

The regional transmission organization PJM dropped the project in 2022 because no construction had been initiated. The Interconnection Service Agreement required that the project be 20% completed by November, 2021. Balico LLC did not propose further action on a pipeline that would be treated as a public utility, and finally cancelled the Chickahominy Power Station project in March, 2022.24

the last proposal to build a new natural gas pipeline to Charles City County ended in 2022 with cancellation of the Chickahominy Power project

Source: Chickahominy Power

The Mountain Valley Pipeline also faced delays because of lawsuits and opposition to permits to cross federally managed land such as the Appalachian Trail. Too optimistically, EQM Midstream Partners and other companies financing construction of the 303-mile Mountain Valley Pipeline projected it would be completed to its connection with the Transco pipeline near Danville in 2019. The permit included an alternative route which avoided National Forest land and did not cross the Appalachian Trail.

The backers of the Mountain Valley Pipeline continued to press for its completion after Dominion Energy chose to abandon the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. After the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved the interstate pipeline in 2017, opponents were unable to get a court to overturn the certificate of public convenience. About 90% of the pipeline was constructed, but successful court challenges to permits issued by two Federal agencies blocked completion of the pipeline projected to deliver 2 billion cubic feet a day of gas of natural gas.

Federal judges ruled that the Forest Service authorization to cross Jefferson National Forest failed to assess adequately the risk of stream pollution from erosion. The endangered species review of the risks to the Roanoke logperch and the candy darter by the US Fish and Wildlife Service was also determined to be insufficient. In April, 2022 the US Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected efforts of the pipeline attorneys to force reconsideration of the two rejections.

The legal rejections required the Mountain Valley Pipeline to re-apply for authorization by the Forest Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The original permits had been issued when President Trump was in office, but there was the possibility that in a second assessment under President Biden the permits would be rejected.

When the lead partner in the project, Equitrans Midstream Corporation, announced the plan in May 2022 to re-apply for permits rather than appeal to the US Supreme Court, the cost of the Mountain Valley Pipeline has escalated from $3.7 billion in 2018 to $6.6 billion.

The pipeline overcame one set of legal challenges in 2022. Courts had blocked plans to use the open-cut process through streams to bury the 42-inch diameter pipe. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) modified its 2017 certificate authorizing the interstate project, granting the Mountain Valley Pipeline the right to tunnel underneath the streams rather than dig a trench. In 2022, Federal regulators also granted a request for a four-year extension of the permits for constructing the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

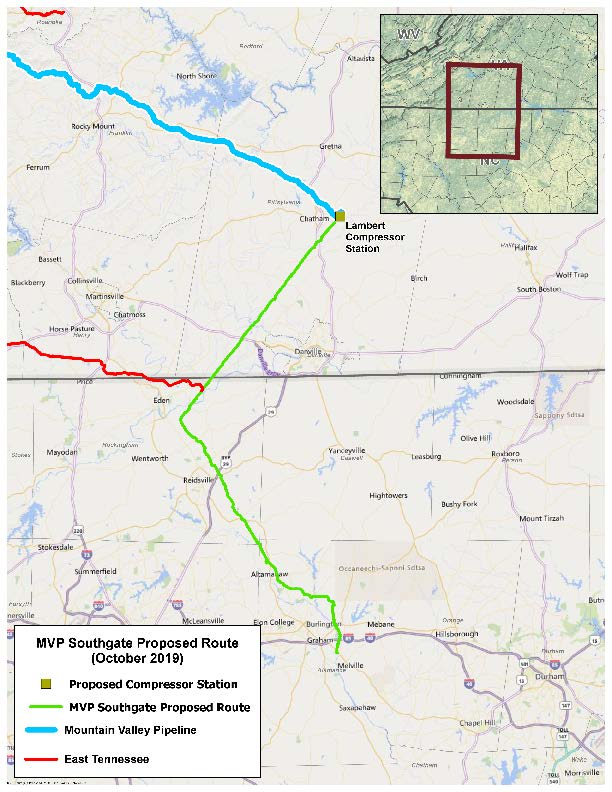

At the state level, support of the Mountain Valley Pipeline shifted in December, 2021 when the Virginia State Air Pollution Control Board denied an air permit for the proposed Lambert Compressor Station in Pittsylvania. That station was required for the 75-mile Southgate extension into North Carolina. The board cited the Virginia Environmental Justice Act passed in 2020, and a Federal court's rejection of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline at Union Hill in Buckingham County, as the justification for denial.

A leader in the Chesapeake Bay Foundation commented after the decision by the State Air Pollution Control Board:25

In response to the denial, the General Assembly shifted all responsbility for such permits to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

The Mountain Valley Pipeline sought to overcome the State Air Pollution Control Board denial through both Federal action and a redesign.

In 2022, the US Congress directed approval of permits for the 303-mile Mountain Valley Pipeline as part of a deal to increase the Federal debt ceiling. The 75-mile Southgate extension into North Carolina was also included in the deal. A year later, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved an extension of its deadline for completing the Southgate project from 2023 to 2026.26

On December 29, 2023 Equitrans Midstream Corporation announced plans to reduce the proposed length of the Southgate extension from 75 to 31 miles. The shorter length eliminated the need for a state permit for the Lambert Compressor Station in Pittsylvania County. The shorter pipeline would have a larger diameter, increasing from 16-24 inches to 30 inches, so it could carry more natural gas.

Duke Energy and a new industrial-scale utility, Enbridge Gas North Carolina, agreed to purchase the gas. They signed 20-year contracts with 5-year extensions, satisfying the need for Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC to demonstrate there was a need for the natural gas to be transported in the Southgate Extension. The extension would pass through the Southern Virginia Mega Site at Berry Hill, where additional gas purchasers could locate.

The earlier 75-mile version of the pipeline had been designed to carry gas to generating plants of just Dominion Energy in North Carolina. Though North Carolina state law mandated phasing out fossil-fueled generating stations by 2050, there was strong support within the North Carolina legislature for the pipeline. The 2050 deadline might be waived, and it was possible for a new customer to make a profit by building and operating a gas-fired power plant until that deadline.

Equitrans Midstream Corporation also notified the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that it planned to complete the Southgate extension in 2028, so the company would be requesting the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to authorize another two-year extension of the construction deadline. An opponent of the project, Appalachian Voices, stated:27

the 302-mile Mountain Vally Pipeline and the 75-mile Southgate extension were designed o bring natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale formations south to North Carolina

Source: MP Southgate, American Pipeline

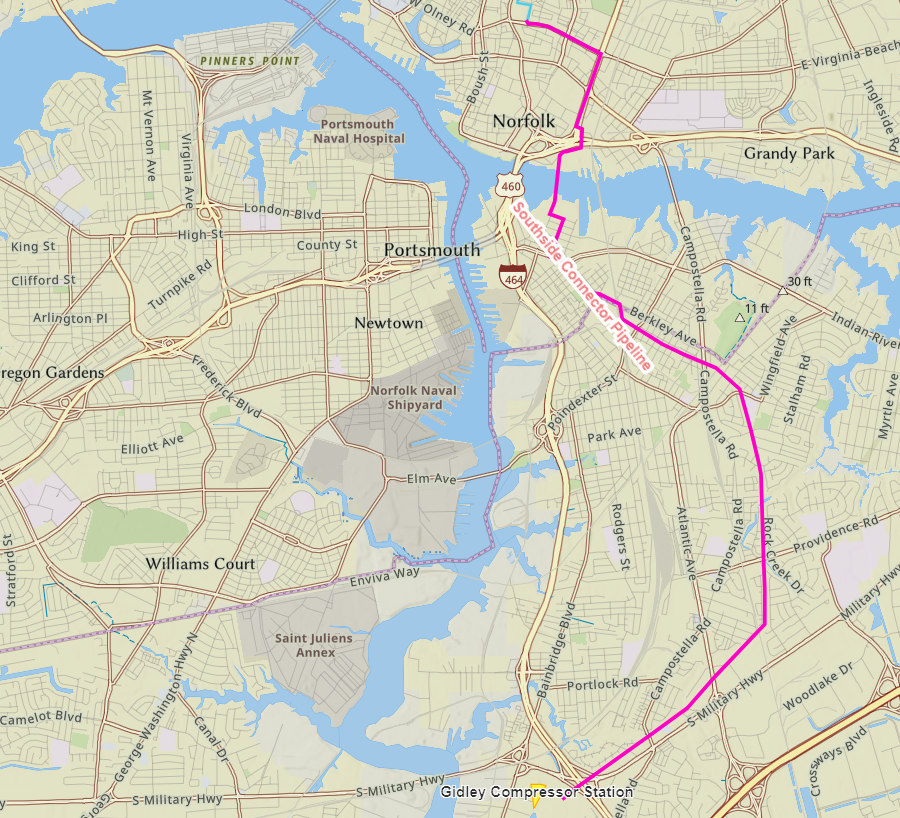

Virginia Natural Gas completed the Southside Connector project in 2019. Nearly eight miles of new 24-inch steel pipe enabled the company to connect its northern and southern pipelines in South Hampton Roads. The Southside Connector enabled both greater reliability and the ability to purchase lower-cost gas, based upon the supply available to the northern and southern pipelines.

the Southside Connector linked two Virginia Natural Gas pipelines when the new pipeline was completed in 2019

Source: Chesapeake Climate Action Network, Eastern VA Anti-Pipeline Education Map

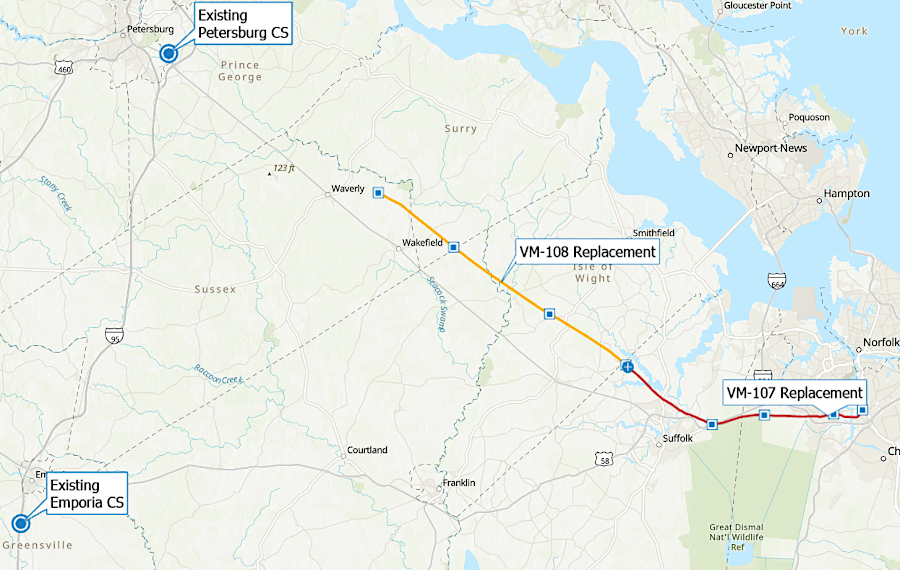

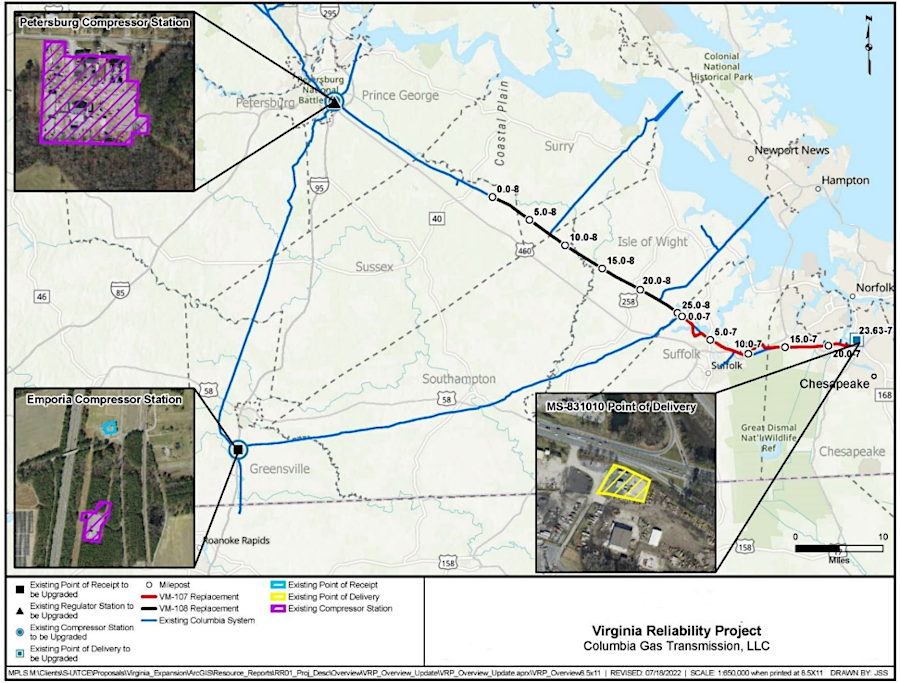

After Dominion Energy cancelled the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, TC Energy decided to increase its capacity to supply natural gas to Hampton Roads. The Virginia Reliability Project was led by TC Energy's Columbia Gas Transmission subsidiary, which was a separate company and no longer associated with the regulated utility Columbia Gas selling directly to retail customers.

TC Energy planned to replace 48 miles of 12-inch diameter pipe installed during the 1950's with new steel pipe, and to expand to a 24-inch diameter pipeline. The Virginia Reliability Project involved pipe crossing through Isle of Wight, Southampton, Surry, and Sussex counties and the cities of Chesapeake and Suffolk, plus upgrades to compressor stations at Emporia and Petersburg.

Virginia Natural Gas agreed to purchase the additional natural gas that would be brought southeast of Petersburg by the Virginia Reliability Project. Virginia Natural Gas had added nearly 75% more customers since the Columbia Gas Transmission pipeline was installed in the 1950's; in particular, the expansion of shipyards had increased demand. The natural gas utility company had tried to increase supply to its customers in Hampton Roads via the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Header Improvement Project, but in 2020 both projects had been cancelled.

A member of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, a state agency with the responsibility to issue or deny stream crossing permits for the pipeline, lobbied local officials to express support. Due to his advocacy, he planned to recuse himself from votes on the pipeline's permits.

In 2022, the mayor of Virginia Beach made clear his support for TC Energy's Virginia Reliability Project:28

the Virginia Reliability Project of TC Energy was designed to upgrade an existing pipeline to increase delivery of natural gas to Hampton Roads

Source: TC Energy Corporation, TC Energy Virginia Reliability Project Map

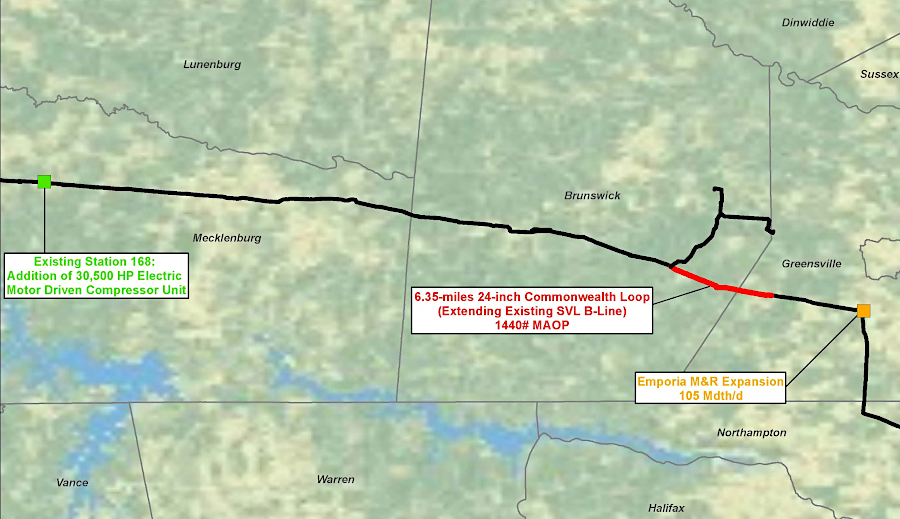

Williams, owner of the Transco natural gas pipeline, also sought to increase the supply of natural gas to Hampton Roads after Dominion's Atlantic Coast Pipeline and Virginia Natural Gas' Header Improvement Project were cancelled. Williams proposed the Commonwealth Energy Connector project, adding 6.3 miles of new pipeline in Brunswick and Greensville counties. Compressor station upgrades would convert them to run on electricity rather than gas in the pipeline. Conversion to electricity would reduce greenhouse gas emissions from pipeline operations and also increase the amount of gas available for sale to customers.29

the Commonwealth Energy Connector included construction of over six miles of a 24-inch-diameter pipeline

Source: Williams Corporation, Commonwealth Energy Connector

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) published the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Virginia Reliability Project and Commonwealth Energy Connector Project on September 15, 2023. For the Virginia Reliability Project, that report assessed:

the Virginia Reliability Project included upgrading the Emporia Compressor Station in Greensville County

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the for the Virginia Reliability Project and Commonwealth Energy Connector Project (Figure 2.1-1)

For the Commonwealth Energy Connector Project, the Environmental Impact Statement considered:

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission did not evaluate potential climate change impacts resulting from the increased capacity to deliver natural gas to Hampton Roads, which was the primary reason for environmental organizations to oppose the expansion projects. That omission caused one of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission commissioners to partially dissent when the agency issued a fnal approval in November, 2023.

The Nansemond Indian Nation objected at one point to the Virginia Reliability Project. New construction would go through the tribe's traditional territory on the Nansemond River and in the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. TC Energy acknowledged the tribe's relationship to the land and agreed to fund an ethnographic study by the tribe to identify cultural resources, and the tribe withdrew its objection.

The Environmental Impact Statement concluded (emphasis added):30

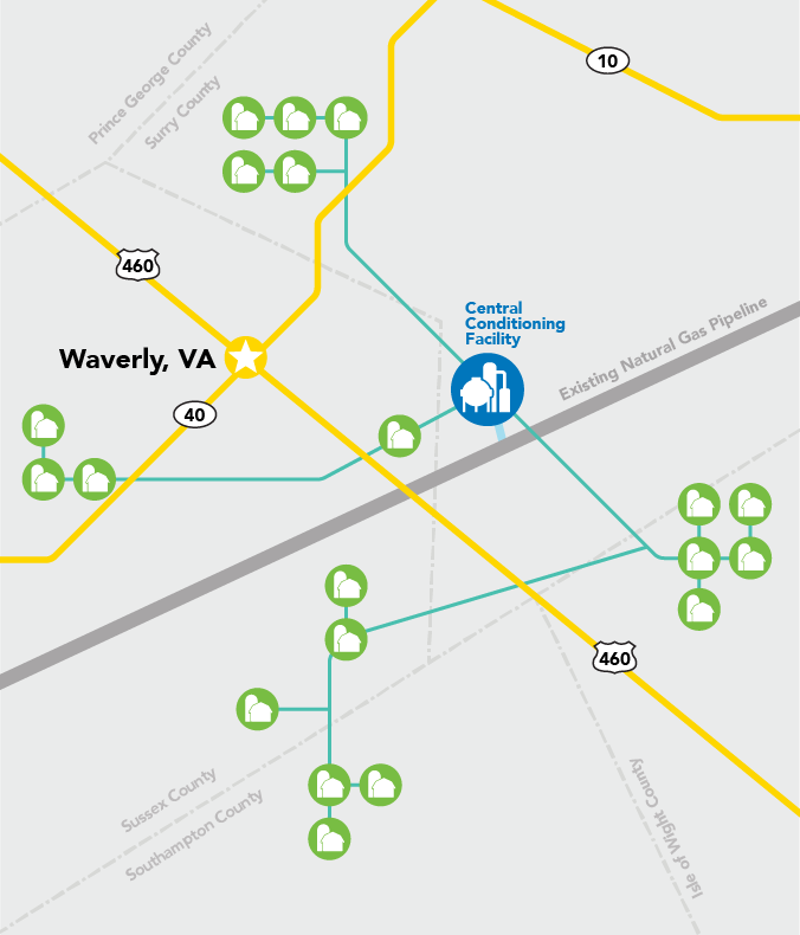

An unusual natural gas pipeline was proposed in 2018 by Align Renewable Natural Gas, a company created as a joint project by Dominion Power and Smithfield Foods. At the time, Dominion Power was pressing for approval of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Both companies wanted a high-visibility project to demonstrate they were reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

They planned a 65-mile network of pipelines to collect gas from hog manure lagoons at 20 farms in Surry, Southampton, Sussex, and Isle of Wight counties and transport the gas to a central processing plant in Waverly. The processing plant would remove the 30-35% of carbon dioxide and the smell-producing hydrogen sulfide, then inject what would be 99% methane into a nearby Columbia Gas of Virginia pipeline.

Capturing gas from scattered farms and building new pipelines to transport it to a central processing plant might not have generated a high return on investment for the capital invested by Dominion Power and Smithfield Foods, but burning methane reduced the companies' greenhouse gas impacts.31

If the world transitions to generating energy from carbon-free sources by 2050, existing natural gas pipelines will need to be re-purposed or abandoned. Electricity coming from renewable resources could provide 80% of the energy needed in buildings and for car/truck transportation, and hydrogen could provide the remainder for industry.

In that scenario, gas pipelines leading to residential and commercial buildings would have no value for energy transmission; hydrogen will not be pumped into structures like natural gas. Small pipelines might be useful as routes for fiber-optic and other cables, even electrical power lines. Large pipelines with pumping stations designed to move natural gas may be abandoned in place, becoming archeological resources as relics of a previous era.32

pipelines were planned to deliver gas from hog manure lagoons on 20 farms to a central processing facility at Waverly

Source: Align Renewable Natural Gas, Projects

Dominion revised the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline to minimize conflicts, but the route still crossed the George Washington National Forest and Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia

Source: Dominion, Proposed Route Map - Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Dominion dropped plans for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline in 2020

Source: Friends of Nelson, Lessons Learned Complete Series

the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Source: Atlantic Coast Pipeline

gas reservoirs are no longer concentrated along the Gulf coast, so the gas pipeline network will be expanded to move natural gas from new production areas to customers located in urban areas and to power plants in rural areas

Source: US Department of Energy, Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer, United States Shale Basins (Exhibit ES-1)